RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

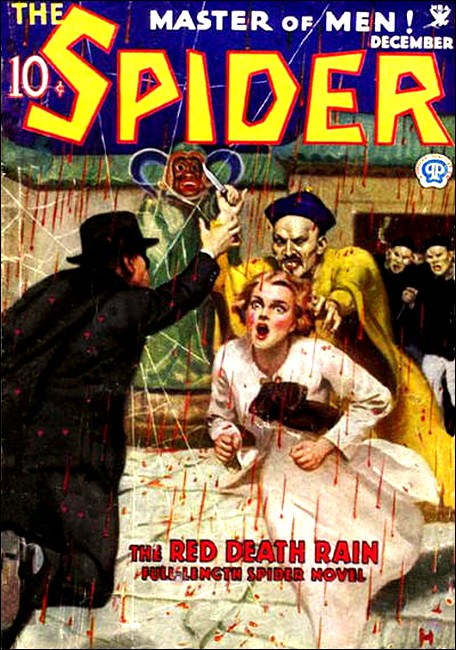

The Spider, December 1934, with "Doc Turner's Murder Mask"

Death strikes with living flame on Morris Street—leaving no sign save charred, battered human wrecks to mark its passing. And Doc Turner, stalking the killer, becomes, himself, a fugitive from the law!

ANDREW TURNER'S white-topped head jerked up, his age-seamed face tight with apprehension. He peered near-sightedly through the murky, indoor twilight, trying to pierce the veil of smut and steam hazing the glass panel of his store-door. Outside, the Saturday night gabble of Morris Street had checked suddenly to a shocked silence—as if a gigantic hand had been laid across the lips of chaffering, shawled housewives and had stuffed the raucous cries of the pushcart peddlers back into their leathery throats.

Then, abruptly, a woman screamed. Tumult beat once more against the front of the ancient drugstore. But now it was a roar vibrant with shouting, hysteric voices, with the pound of running feet; and the blue knife-edge of a shrilling police whistle sliced across the mounting clamor.

Shadowy figures rushed across the gray screen that blurred Doc's view of the street, waving spindly arms above forward-bent heads in an ecstasy of horror. Under the nicotine-edged bush of his mustache the old pharmacist's lips twisted. He pushed out from behind his counter, his gnarled hands lifting already to the doorknob that was still yards away.

The door crashed open before Turner could reach it, and Abe, Doc's undersized errand-boy, plunged in. His protruding lips were blue, his eyes deep sockets of black flame in the grime-smeared pallor of his Semitic face. His voice was a squeezed, muted scream. "Ai, Meester, Toiner! Eet's Jeem O'Neill. De Teeng's got eet Jeem O'Neill dees time."

A groan wrenched from the druggist's throat as he passed the lad. "Again! Good Lord! Hasn't it stopped yet?"

Then he was out in the streaming throng, was being swept by the crowd along a debris-strewn sidewalk, under the glare of lights wire-strung from building fronts to leaning poles at the curb. Minutes before, those lights had seemed festive in the holiday spirit of the market evening; now they flicked across white, drawn faces, glinted from fear-widened eyes. From eyes in which, despite the panic they mirrored, there glowed also a queer eagerness, a morbid lust for the gruesomeness toward which they strained. In the emotion-starved, toil-ridden lives of these slum people any excitement was welcome. Even the shock of grisly death. Even the poignant stab of a mysterious menace that might strike next into the home, the breast, of any one of this polyglot mob.

The human flood swirled around the corner next above that which Andrew Turner's pharmacy had occupied for so many years, piled against a human dam—a close-clotted, quiveringly silent mob staring inward at something that drained the color from swarthy cheeks. The raw blaze of Morris Street's illumination was somehow repelled by the gloom of this sleazy side-street and it was a narrow, dark chasm between man-built cliffs. The reek of man-sweat came to Doc's big nose, garlic- laden breath, the stench of unwashed bodies. But his nostrils flared to another scent threading those familiar odors—the acrid, pungent odor of charred flesh.

Turner touched a big, over-coated shoulder in front of him, and said in the curiously hushed tone one uses in the presence of the dead, "Can you let me through, Tony?"

The man twisted. The pendulous dewlaps of his huge face were the clammy hue of a dead fish's belly and little lights crawled in his dark eyes. Then recognition cleared the quick resentment from his expression. "Shoor, Docator. Shoor t'ing." His mountainous frame surged sideways, opening a gap into which the little druggist slipped. "Letta Docator Turner t'rough," the Italian called. "Letta heem go in."

A murmur went through the crowd. "De droogist ees here." "Sure Doc, go roight ahead." "Shove over an' let Doc Toiner git by." In all the alien accents of that polyglot gathering the message was passed on, and the crowd slitted, making way for the little man as it would have for no one else.

Doc Turner was through now, to where a cleared space was a semi-circle about a brownstone stoop. A flickering gas-jet, high in the ceiling of the vestibule at the stair-head, spilled fitful luminance down the stone steps, touched their spiked railings of rusted iron and half revealed a something grotesquely draped over the one to the left. It hung there, broken over the iron.

Breath hissed from between the old pharmacist's teeth as he peered at the shapeless bundle and saw the upside-down head twisted toward him, the agonized contortion of what once had been a face but was now a seared, crooked mask from which dull-white marbles stared sightlessly. Only the head was burned. A dangling arm trailed green-white fingers on the concrete. Brawny shoulders hung flat against the square filigree of the newel-post that had been bent by the impact of the thing which hurtled down upon it...

IT was not the crisp cold of the early winter evening

that shook Doc's slight frame as with an ague. Death, in all its

many forms, was an old, old story to him. But this...

Someone tugged at the sleeve of the druggist's stained alpaca jacket. Turner came around slowly. Short as he was the stooped woman was shorter; he could see the stitching in her sleek black sheitel, the wig donned by the orthodox Hebrew woman on her marriage day. The hand on his arm was claw-like, the parchment skin of the face turned up to his incredibly wrinkled. From the depths of two bony wells tiny black eyes glittered with the ready tears of the very old.

"I seen heem fall down," her thin voice quavered. "Ai! From de feeft floor vinder he fell und hees head voz all on fire like a star cast down by the handt from Jehovah. Look eet..." She stabbed a twisted finger upward to where a black rectangle gaped under the tenement's jagged cornice. "Mein bester tenant. Alvays on de first hees rent he paid, und so quiet, all alone in de two rooms ahp dere."

Her fleshless lips quivered. "Leesten, Doctor dear. Maybe you know somebody vat vants rooms cheap, hah? Eet ees ah goodt house; qviet and clean. Efery veek I sveep de halls mit mein own handts undt de kinder I shush ahp ven dey too matsch noise make." To a stranger the inquiry might have seemed shockingly callous, but Doc knew the tragic anxiety that impelled it.

"Mother Ginsberg," he said gently, "that's the third tenant you've lost this way, isn't it?"

The old woman's face went two shades grayer; her hands moved out in the immemorial gesture of despair that is a racial heritage. "Eef vunce more eet heppens dey veel all moof oudt, next mont' dere vill be nobody left. Undt..." Her throat seemed to squeeze shut; the seams of her countenance were tiny rivulets of unashamed tears.

"And you will lose your house to the mortgage-holder, your house that Yankel left you to take care of in your old age. That's—" Doc stopped abruptly as an ambulance gong clanged alarm up the street and a broad-shouldered detective came slowly down the steps. "Hello Leary. On the job?"

The plainclothesman's face was grim, unsmiling. "Hello Doc. Yeah. I'm on the job. God help me. This is like the other two. O'Neill was alone in the apartment. Nobody seen nothing, nor heard nothing till there was a scream an' he come plunking down. Door locked, not jimmied nor nothin'. They're scared gutless in there, but far's I can make out they're tellin' the truth an' there ain't been a soul seen in th' house that don't belong there." A mouth corner lifted, brown spray jetted from the small aperture, splashed on the sidewalk. "Cripes! I'll be believing myself in this malakh ha-mavet, this Angel of Death, those yids are jabberin' about before I'm much older."

A white-clad interne shoved out of the crowd. Leary turned to him. "Yuh get a break this time, young feller. Get your book out an' put down 'dead on arrival.' I'm phonin' for the medical examiner an' the morgue wagon."

"Okay!" A red-covered notebook snapped out of the ambulance man's black bag and a pencil poised for immutable routine. Doc's lids narrowed and his mouth was bitter. For those two another mick was gone from among Morris Street's hundreds, another grave would soon be dug in Potter's Field. The incident would ripple in their world of pinochle and bridge, then vanish from their memories. What were these here but a bunch of poverty-stricken, worthless micks and kikes and heinies who should have stayed where they belonged in their vague homelands over the eastern horizon...?

Doc Turner's gaze drifted from the gargoylesque corpse on the bent railing to the shivering little widow, to the crowding faces that somehow seemed to be fastened on his with mute appeal. They were his people, these whom he had served for longer than he cared to think. Strangers in a strange, bewildering land, he was their only friend, their adviser in trouble, their indomitable protector against the ravening coyotes who prey on the helpless poor.

His thin arm was tender across the bent shoulders of the ancient mother of Israel. "Don't worry, Mrs. Ginsberg," he said. "We'll stop this business."

JACK RANSOM glowered at the scale on Doc Turner's

prescription counter. "There's no rhyme or reason to the damned

thing," he growled. "It's some fiend, some lunatic who's killing

for the sheer pleasure of it."

The little druggist looked very old, very tired, as he slumped in the swivel chair before the cluttered desk that bulked at one end of his back room. "No, Jack. The murders are done too cleverly for any maniac." By contrast to the youthful vitality of the carrot-topped, hulking garage mechanic who had been his companion in so many strange adventures on Morris Street, the old man seemed smaller, feebler than ever. "Each crime has been worked out in the same way. Mary Sartel, Sol Eisenberg, and Jim O'Neill were all alone in their flats when he got them. Their doors were locked and no one was seen to go in even though in each case it was early evening with the children racing up and down the stairs of that house. Every time it was first known that there was anything wrong was when they crashed through the glass of their closed windows and hurtled down to squash on the pavement below."

"What gets me is the way their heads are all afire when they fall and the rest of them not touched." Jack shuddered. "It's—unnatural."

Moodily Doc probed the edge of his desk with an acid-stained thumb. "That's also too devilishly ingenious to be the work of a madman. Once, perhaps, but not three times. No lunatic is capable of sticking to a single course of action, a single complex procedure, for even as long as a week. Mary died on Monday, Sol on Wednesday—and this is Saturday. No. Whoever is behind these horrible deaths may be a devil, but he is as sane as you or I."

"Then why?" Ransom flung the tortured question at the old druggist. "They were poor as—as everybody else around here, and none of them had an enemy in the world."

"You've touched on the crux of the problem, there, Jack. If we could figure out the motive we'd be well on the track of a solution."

The youth's big hand curled into a hairy fist. "How the hell can we do that? Between us we know damn near everything about them and we can't think of a single connection between the three, of anything that might tie them together and bring in someone else who might be the killer."

Doc's head came up, and his faded blue eyes glittered as with fever. "Jack! There is a connection between them, so obvious that we haven't thought of it."

Ransom's voice was sharp, excited. "What? What is it?"

"That they all lived in the same house. It's as plain as the nose on your face..."

"And as meaningless." Jack was irritated, showed it. "Though I can't understand," he went on, "why anyone stays there with what's happening. I'd have gotten out long ago."

The eager glow that had come into Doc's eyes did not fade. His attention seemed only half on Ransom's words. "Those people cling to one place; in the old country they were rooted to the soil, lived and died in the same hovel. They haven't yet assimilated our New York wanderlust. Lucky for Ma Ginsberg that it's so, or we'd be looking for a bed in some home for her. She and her husband worked eighteen hours a day and starved themselves so that they'd have the building's income as security for their old age, and she has turned down some mighty good offers for it." Doc drummed on the desk-top. "I remember when old Yankel was in here for me to read over the papers. He wouldn't trust a lawyer but he took my word for it that everything was straight."

Jack moved restively. "That's all very nice, but I don't see what it has to do with—"

"I do, my boy," Doc interrupted. "I do. I see many things, one of which is that there will be another death in the Ginsberg tenement tonight if we don't move fast. Listen..."

Even in that deserted, silent store, Doc's voice dropped to a cautious whisper... Once, as the old man talked, Jack broke out with a snapped—"The dog! The yellow-livered dog!" Then he was again listening intently, taut muscles ridging the bold lines of his out-thrust jaw.

THE houses in which the people of Morris Street drag out

their weary lives shoulder close along the side-streets right-

angling into it, and between their gaunt rears there are the

narrowest possible back yards of broken concrete. At night these

dreary slits are straight-sided gullies of ominous blackness from

which rises crazily askew, tall poles connected with the white-

washed brick at either hand by sagging clotheslines.

Hours after what was left of Jim O'Neill had been taken from the stoop of Ma Ginsberg's tenement on Lansing Place, a furtive movement might have been detected in the yard behind, had there been anyone awake to see. Two figures glided briefly across the gray-black glimmer of stone paving. A momentarily incautious toe stubbed against a garbage can; then the black forms of the prowlers melted into the blacker shadow that edged the tenement's basement wall. Silence invested the areaway once more, silence broken only by the soft hiss of a wandering breeze along down- arched ropes, and the creak of a rusted pulley.

Minutes passed, long minutes that dragged slothfully over the crouching, tensed watchers. The cold penetrated through Doc Turner's shabby ulster, stung sharply the sluggish stream in his old veins. From the pale loom of the house-walls opposite lightless windows stared blindly at him. Far above, a slab of sky was dimly luminous with the city's night-glow, laced across by the spider-web of the clotheslines. To one side a forgotten union suit danced like a pirate hung in chains on old Execution Dock...

As the old druggist looked shiveringly on these things, Jack Ransom's fingers closed suddenly on his arm, gripped tight.

Somewhere in the urban gully, a window scraped in its frame. A clothesline tautened, was a straight thread. Then against the pallidness of the opposite tenement was a black-lumped excrescence. The odd mass swung free in mid-air. Silently it moved across space and now Doc could see that it was the form of a man, working hand over hand along the rope—working silently toward the pole that was common to the house from which he came and the house where the death doom had struck three times!

Even to Jack, close against him, Doc's breathed words were scarcely audible. "Third floor. Quick, son. Quick!"

Noiseless as was the one above, Jack's rapid strides were more silent. He had a foot on the sill of a cellar window; his long, almost simian arms were stretched upward; his hand caught, closed on the edge of a fire-escape platform. He chinned his chest level with the flat ledge of strap-iron, got one knee up to it, then the other. He was on the fire-escape, was lying flat and reaching down toward Doc Turner, his arms stretched to their uttermost.

The little man sprang. Jack's hands caught the bony, thin wrists, swung Turner effortlessly up. Now they were soundlessly climbing the vertical ladder of the escape—climbing to meet the killer who had passed the central pole, who was swaying nearer and nearer the wall up which they clambered.

His muscles oiled by youth, his lungs powerful within his barrel chest, Jack leaped ahead of the aged pharmacist—by two rungs, by four, by a whole Argot of that vertical ascent. Doc's spindly legs pumped valiantly, his gnarled hand gripped rod after flaking rod, pulling, pulling. He was panting; a tight band constricted his temples and his thigh muscles throbbed with dull pain.

He looked up to call to the youngster to wait—saw that the rope-walker had reached the third-floor fire-escape, was climbing its rail. He saw Jack's bulk fill the square hatch of that same platform, surge through it. The two dark forms merged into one.

A guttural exclamation came down to Doc, the spat of a fist on flesh. The confused mass above him split. The slighter shape reeled backward, thudded against the rail. Turner froze, clamped against the ladder just above the second floor, and his old eyes ached with watching. The issue was joined; he could not reach them in time to help Jack. But the youth's first blow had gone home. The other was dazed, clung feebly to iron. Breath whistled in relief from Doc's tight chest.

Ransom moved lithely toward his quarry, crouching warily in the pugilist's pose, taking no chances. The killer's arms swung out in a curious gesture. There was something in his hand, something that caught a stray light-beam and glinted metallically.

Blue flame jetted from whatever it was he held. It hissed across the dark. Hot flame that had already seared the life from three people surged around Jack Ransom's head! The old druggist's nerveless hands tightened on the ladder rungs as he watched the death-jet strike.

Jack's head was a red-glowing globe, there above, a globe heat-red in the hiss of that consuming flame. Miraculously the youth lunged on, toeing toward the murderer...

A GUTTURAL ejaculation ripped the night. The blue lance

of flaming death was gone, and Jack was almost on its wielder,

his great fists flailing. The killer ducked, was over the railing

like a flash. His dark form lurched outward. He was

falling...

No! That falling figure uncoiled like a released spring. Its hands arced, caught the line along which it had come. A pulley screamed protest and the man was swinging once more, apelike along the rope, was retracing his route with unbelievable speed.

Jack whirled, slid along the frail fence, was himself over it and following his antagonist, grimly following along that perilous path while unencumbered space pulled at his waving feet. Below, the stone pavement waited for the downward plunge of a hurtling body, for the pulping smash when it struck.

"Jack!" the white-haired witness screeched. "Come back! For God's sake come back. Let him go."

"Not on your tintype," the youth's cheery voice responded. "Not if I know it." The ten-foot gap between hunter and hunted was closing. The pole bent inward to the weight of those two swinging bodies—lifted a bit as the foremost reached it, worked around to the other line that arced to his lair.

The killer's legs were folded around that pole; his arms were free. Doc gasped as he saw his intention, scrambled down to the platform beneath, leaned outward. Blue flame sprayed once more from the murderer's queer weapon, but not at Jack, midway across. It spat, rather, at the rope the slayer had just quitted, the line that still surged to the drive of Ransom's pursuit. And instantly that line was burned through!

One end whistled through the far pulley that had held it, sagged back toward the wall. The other plunged down with the weight of Jack's twisting body, swept with him toward the building-wall he had just quitted—straightening for the final plunge to destruction!

Doc's reaching hands snatched at the lashing length of loose line as it came toward him. It was in his grasp. "Hold tight!" the old man shouted. He whipped the rope around the rail over which he leaned, whipped it over again as Ransom hurtled past him. Once more he flashed it over, just as it pulled taut, twanging.

The pulley above him groaned protestingly. The thin rail bent to the jerk, bent more and more. Snubbed though it was, the rope cut into his clutching palms, cut till his palms were wet with blood. He whimpered with the pain but held on...

And abruptly the drag on the rope was released! It pulled easily around the rail, so suddenly that Doc reeled back against the wall behind. But he did not feel the bang of his head against the hard brick. He felt nothing but the stab of despair as he listened for the thud of Jack's body on the concrete below. The instant before it could come was long, long enough for him to pass through a hell of contrition, of self-blame for having led the carrot-topped grinning youth he loved to his death...

"All right, Doc," Jack's voice sounded from down there where Turner feared to look. "Come on down."

Ransom was on the outside of the platform below, was peering up at him. His smile flashing, through the dimness, was the most welcome sight of Doc's long life. "Can you manage it or shall I climb up and help you?"

The old druggist breathed a silent prayer of thanksgiving, started the descent. Instants later he was beside Jack on the cheated stone of the yard, was looking earnestly through the strange sphere of meshed wire that enclosed Ransom's head, a globe of fly-screening matching one that he himself wore. "Sure you're all right, my boy? Sure?"

Ransom rubbed a shoulder ruefully. "Well," he grinned, "I'm pretty sore here. That jerk when the rope caught wasn't any joke. But it was lots better than being smashed or burned alive."

"It worked then? The screen?"

"Like a charm. But I can't understand it. That flame was hot, what I mean."

"Ever read about the Davy safety lamps, son, that the miners used to carry in their hats before the days of electricity? Just cages of metal mesh around candles or oil lamps—but the otherwise naked flames never ignited the inflammable gases in their underground workings because the metal dispersed the heat. The principle of these is the same—reversed... But—was I right about the killer—was he...?"

"I don't know, Doc. He had a hood over his face. It might have been anyone."

"Too bad. There isn't any safety for the folks in that house till he's behind the bars. We'll have to—"

"Put them up, you guys. High!"

FEET clumped in a shadowy cellar doorway. Doc twisted to

their thud, to the gruff command. Out of blackness loomed the

spread-legged outline of a big-shouldered, tall man in whose hand

a bulldog revolver snouted. "Up! And don't try any tricks or I'll

let you have it."

"Leary!" Turner's arms started to come down as light took the detective's broad-planed face; but they straightened upward again at a warning thrust of the pointing gun. "Thank God you're here! We've just headed off the murderer. He's somewhere in—"

Far-off a siren howled.

"Headed him off, hell! See any green in my eyes? How about you bein' the murderin' bird yourself, you an' that redheaded pal of yours? I've had you spotted a long time, pullin' all that killin' around here an' struttin' about as the guy that's better than the whole force... Lucky thing I called the station just after someone phoned there were prowlers in this backyard, or you'd of popped off some poor bozo an' claimed he was the fire-killer. You won't have a chance to pull that alibi this time."

Light burst on Doc. Suddenly he was afraid. "I—" he began.

"Skip it. You're goin' in soon as the radio car gets here and you'll have plenty of chance to tell your yarn—to the D. A. Better think up a good one, one that'll take in them cages you're wearin'. They're the tip-off. I don't know how you worked them but sure's shootin' they've got somethin' to do with the way them guys' heads was burnt."

Leary was taking no chances. He kept his distance, though the gun in his hand was rock-steady.

"Look here, you fool!" Doc snapped. "This is just a scheme of the killer's to get us out of his way. He's the one who phoned..."

"Button up or I'll let you have it. Cripes! I ought to do it anyway before some shyster mouthpiece gets a chance to spring you." The siren howl was nearer. "Gimme an excuse. Please."

The old druggist knew the detective meant it. There is no one more dangerous than a scared bully with a gun in his hand—and this man was frightened of the flame-death, frightened so that the whites of his eyes glistened and his thick mouth twitched. Only iron discipline kept his finger from tightening on the trigger...

And somewhere behind, one watched, smiling evilly, from a darkened window—watched as his stratagem worked to its inevitable end, leaving his path clear once more to the house whose inhabitants he had doomed to horrible destruction. The two who might have beaten him stood stiffly under the menace of the policeman's weapon. The oncoming siren wailed, brakes squealed...

At that instant, from somewhere above the three, water gushed down in a miniature torrent! It drenched Leary, momentarily blinded him!

"Meester Toiner! Jack!" a high voice piped. "Qveek!"

Ransom sprang. His fist flailed against the detective's jaw, his other struck down at the revolver. The gun clinked to the paving. Leary collapsed like a ripped flour sack.

From the obscurity of the cellar, someone shouted; heavy feet clumped, coming fast. Ransom's surge up to the fire-escape just overhead was a flicker of smooth action. He had turned, had lifted the pharmacist, and the two had vanished into an open window in seconds.

Two cops, brass buttons flashing, guns ready, pounded out into the yard. But there was nothing there for them save Leary's limp figure sprawled in a watery pool, and the mocking gloom of the silent yard.

"Abe!" Doc whispered to the small boy whose scrawny, bare legs shivered beneath his too-short nightshirt. "How in the name of all that's holy did you get here?"

The urchin shrugged knife-blade shoulders. "Ai, Meester Toiner. Dun't you know eet dot Meesis Geensberg ees mein grandmommer? Mein mommer she voz ascared de old lady should sleep alone tonight und so I come to take care from her. Abie de boy detecatiff is ascared from no one und nottings."

The posture he struck was somehow not ludicrous. "I hear ah noise in de yard, I creep to de vinder veed de noiseless tread from de Eendians. Hah, I teenk, de keeler is below und Abie de peerless trecker from de vilds is on hees trail. Mitout ah sound I poosh ahp de gless und mein headt is like ah mooting shedow as I peer dahn in de cenyon.

"Hah! Vot ees dees I see? Mein Chief und hees faitful retainer ees in de hends from de enemy. Mein keen brain voiks like lightneeng. Ah pot from dees vater ees in de seenk. I seize eet in mein strong hands, hoitle eets contents dahn upon de destard who holds mein friendts een thrall. Und—de tables are toined!"

JACK chuckled. "You brat," he grunted fondly. "Trust you

to turn up at the right time with some goofy stunt that just fits

the case." He lifted the mesh cage from his shoulders, tossed it

on the vague rectangle of a tumbled cot. "Phew," he exhaled.

"Glad to get rid of that."

Doc had his off too. "They are clumsy. But we'll have to get them on again as soon as the cops go. We're not through yet."

Abe was staring, big-eyed. "Nu! Vot for foolishness ees dot? I—" He stopped suddenly, jerking to a pounding on the inner door of the flat. "Ai—de cops. Qveek, get een de closet."

He pointed to a huge wardrobe. Jack slid into it, Doc after him. The door closed on them and garments were close about them, rank with the musty, peculiar odor of the very old.

The panels were thin, and barely muffled the ominous rapping of the law. They heard the rumble of moving furniture, heard hinges scrape and the old woman's querulous quaver. "Vot ees? Vy you vake me de mittle from de night, hah?"

"The guys what's doin' the killin' are somewheres in the house, lady. They got away from us in the yard—maybe they clumb up the escape to this flat."

"Ai! Leetle Abie's in dere!" The listeners could visualize the wringing of thin transparent hands, the terror in the ancient eyes. "Right een dere vere ees de excape."

"All right, don't t'row a fit. Let's get in there and see." Footfalls pounded with a rush, milled just outside their covert.

There was a snort, a gurgle. Then Abe's thin tones, sleepy, followed by a yawn. "Who—who's dere?" Startled. "Grossmutter! Vot ees? Vot do de cops vant?"

"Don't get scared, kid. We're lookin' fer some prowlers wot's somewheres around. T'ought they might've come in here t'rough that window."

"Chee! Maybe—baht eet couldn't be. Look eet, mein cot right under de vinder ees. On me dey moost got to step eef dey come een."

"Hell! That's right, Jim. They'd sure have waked the kid. Come on."

"Wait," Leary's voice rumbled. "Wait till I light this butt." The crackle of a striking match came through the wardrobe door, and an icy hand squeezed Doc's heart. The masks—thrown carelessly on the cot! Leary would see them...

But he hadn't. "All right," he growled. "Come on. Keep that window closed and locked, kid, and yell if you see anyone out there. We'll be somewhere in the house."

The sounds of the officers' presence moved away, the flat door slammed. Turner felt Jack's hand move to the screening panel, grabbed it with his own. "Hold it a minute," he whispered. "I'd like to avoid having the old lady see us if I can."

"By me een here you sleep, Abie mein gold. By your old Grossmutter so she can know you're all right." Mother Ginsberg's command chimed in with Doc's wish.

"All right, Grandma. You lie down and I'll get my blankets. I'll be right in." Bare feet padded, nails scratched covertly. "Meester Toiner. Jack. You kin come aht."

They did so. Doc looked around.

"That was a smart trick, Abe," he said, "pulling your cot over to the window. If it hadn't been for that they'd surely have searched the room and found us. But how is it they missed the masks?"

"How ees it?" The little fellow's grin was impish. "Dey vasn't here, dot's how eet ees. Out de vinder I trew dem."

"Good boy! But get inside now, with your grandma. I don't want her to know we're here."

"Baht—"

"But nothing. You've done your part, now get out of here." Doc's hand stung on the boy's scantily-covered buttock. "Get!"

Abe was gone. Turner's face was bleak as it swerved to Jack's.

"Well, Doc, what now?" the latter asked.

"We've got to get those masks back. The killer isn't through yet, and he's got to finish his job tonight."

"I'll climb down and look for them."

Ransom took a step toward the window—and halted short.

AGAINST the graying dawn the aperture showed no longer

empty. A figure crouched there. As the youth saw it, it slithered

into the room. It was tall, gaunt, a shapeless statue of doom

cloaked in black from head to foot. Through slits in a black hood

eyes glittered, and a hand poked out from the ebon folds of its

robes—a hand that menaced the rigid two with a slender,

double tube of metal from which a thin rubber hose snaked back to

obscurity.

"Good morning, my friends." The slow, guttural words dripped from behind the ominous hood. "Don't bother to look for those ingenious masks of yours—you won't need them. You will need nothing more in this world except two graves."

"Good morning, Rand Barker." The mysterious robe jerked. Doc Turner spoke on, calmly as though he were behind the counter of his store. "I was about to call on you."

The apparition's queer weapon was steady again, pointing at the old druggist with infinite threat. The intruder grunted, chuckled with quick recovery from his startlement. "Touché. You are more clever than I thought. How did you know?"

"A bit of information, a bit of thought. It was evident that the motive behind the gruesome murders occurring here could only be to frighten the tenants out so that Mrs. Ginsberg would lose the house. But its income is very small, not enough to justify such methods.

"Then I remembered that you were the second mortgagee, that you lived in Fainton Place, right back of this house, and that you had a son-in-law in the Borough President's office. Recalled an item in Monday's newspapers, that the Board of Estimate would decide, Tuesday next, the location of the new bridge across the river and its approaches. If you had advance information that this property was involved you would know that its value in condemnation proceedings had increased tenfold, would be eager to seize it before Mrs. Ginsberg was apprised of her good fortune.

"But time was short, and your scheme had not yet worked. You must strike again, tonight, or your previous efforts would have been in vain!"

"Clever! Very clever! You knew, of course, that in my younger days I had been a trapeze artist, and that I had kept myself in trim; you figured out how I managed to attack and escape unseen. I regret, Doctor Turner, the necessity for wiping you and your companion from my path. You haven't those masks now, to save you."

The dark figure tensed. The black finger on its strange tube jerked. Blue flame hissed out.

But Doc had dropped, on the instant, to the floor. The death- blast swerved downward. Jack left his feet in a catapulting dive. The blue heat jerked to meet him and the acrid odor of singed hair was pungent in the little room.

Doc's hand stretched out, clawed at Barker's robes—clutched and pulled out a long slim cylinder, jerked it from the trailing tube attached. The reptilian hiss continued, but the flame blinked out.

Ransom's fist crashed against the killer's hood. His other fist dove into the black-cloaked one's midriff. It lifted the murderer a foot from the floor, crashed him thudding against the wall. He slid down, a crumpled, motionless heap.

Feet pounded outside. Abruptly the room was filled with bulking forms. A gruff voice rasped, "Got you! You're covered, Turner!"

A match scratched, lifted to a gas-fixture. Yellow light flooded the drab chamber. Leary's jaw jutted over his snouting gun; his dark eyes smoldered triumph. "There won't be any more killings in this house."

Doc Turner looked drearily up at the detective. "No. There won't be any more killings. Here's your murderer, Leary, and here's what he used."

He held up the steel cylinder that he had ripped from Barker's belt and, so ripping, quenched the death-flame. "A divided tank holding oxygen on one side, acetylene on the other. Ignited, those two gases, mixed, make almost the hottest flame known to science. You've seen it used in welding, Leary, melting steel rails together."

The detective's baffled glance shifted to the black heap that was the beaten killer. "Well," he said slowly, half apologetically. "Well—I'll be damned—I didn't know—"

"Shoor you'll be demned," Abie piped from the doorway. "Any vun vot teenks he's smarter den Meester Toiner is demned by his own foolishness. De smartest guy in de whole voild, und next comes Abie Itzkowitz, de boy detecatiff frum Morris Stritt."