RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

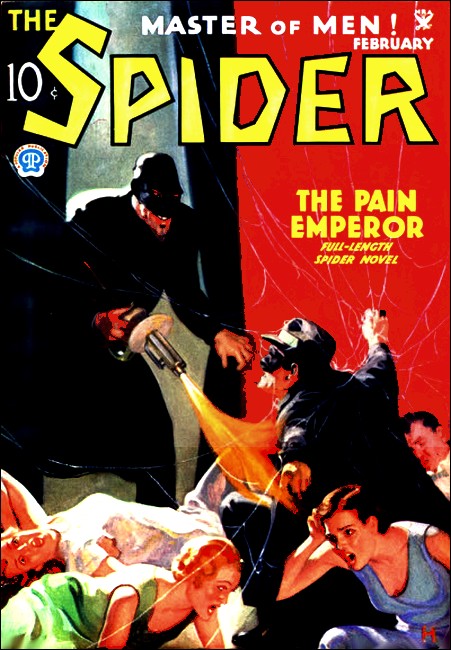

The Spider, February 1935, with "Doc Turner and the Whispering Death"

THE dead man brought in his clutched fingers only a scrap of paper. Yet to Doc Turner it was a message, bloody and legible, that sent him on swift, weary feet to the house where fear sounded in twanging bow springs, and death prowled the darkened halls on silent feet.

THE door-latch of Andrew Turner's drug store rattled, as though the thin man he could see through the glass panel were having difficulty in opening it. "Abe," the white-haired pharmacist called. "Abe. Go get the door open. Something must be the matter with the lock."

"Right avay, Meester Toiner," a piping shrill voice replied. The scrawny, hook-nosed little errand boy scuttled out from the back room, wiping hands on a grimy towel. "Baht eet vass all right a meenit ago."

Doc concentrated his attention on wrapping three different sized bottles and a round, slippery can of Baby Powder. In all his long years he had never learned to manage that difficult task with any degree of ease. He got paper around the odd-shaped bundle, reached for string. The can seemed to take on a vicious life of its own, poked through a fold, skidded across the sales counter, thumped to the floor.

In that instant Abie screamed!

Turner's head jerked up. The door was open and the man was coming in—No!—was toppling in, head first! He hit the wood floor with a dull bump, rolled over on his back.

Doc was around the end of the short counter, was pattering to the front of the store as fast as his old legs would take him. Abie stood rigid above the prostrate man, his swart face grey-filmed, his mouth open and rasping a soundless shriek. The druggist got to the grotesquely twisted form, dropped to one knee at his side. His hand, pushing down for support, went into warm, viscid liquid. He saw that it was blood, that scarlet, arterial blood was welling from a ghastly stab wound sliced through a shabby, frayed-edge jacket into the man's breast!

"Get a roll of cotton, Abe!" Turner snapped. "And a bottle of peroxide. Quick!" The peremptory urge of his command galvanized the lad into movement, sent him trotting to the surgical goods case.

Doc's slender, almost transparent fingers tugged at the buttons of the thin man's jacket, opening it. Beneath there was only skin, gruesomely reddened now by the outpouring life-fluid. The slit from which it came was neatly inserted between two ribs.

But even as the druggist pulled the gaping edges of the wound together he knew that his ministrations would be futile. Already the wizened, unshaved face was pallid, glistening with the waxen hue of death. Blue eyelids fluttered; and bleared, red-threaded eyes peered out of sunken sockets.

Momentarily a sightless film glazed those eyes, then they cleared, and glowing worms of fear crawled in their depths. The colorless lips moved. Doc bent close to catch the husked, almost inaudible words dribbling from between them. His own face was suddenly bleak, his own eyes stony, as he made them out.

"The Whis—the Whisperer. Watch-out... He—Ohhhh!"

A twisting spasm cut off the man's speech. His mouth was suddenly filled with blood; a red bubble formed on his lips, burst... Then he was flaccid, lifeless.

"Here, Meester Toiner. Here ees de cotton." Abe was thrusting a blue-wrapped roll at Doc, and an opened brown bottle was spilling limpid liquid to the uncontrollable shiver of the small boy's other hand.

The druggist looked up at him. "Never mind, son," he said gently. "It's of no use to him. Nothing will ever be of any use to him again."

"What'sa da matt', Doc?" another voice, raucous, put in. "Is he deada?"

Turner twisted, saw a leather-jerkined man standing over him, saw faces crowding the doorway. Faces alight with the morbid thrill that is almost the only relief to the poverty-stricken, drab lives of the denizens of the slum centering about Morris Street.

"Get out, Tony!" Doc snapped, low-toned. "Get out and close the door."

"Buta—buta I wanna a stamp."

"Get out, I said." From under their bushy, white brows the druggist's eyes of faded blue clashed with the black ones above him. He hadn't raised his voice, this frail old man, but the brash one backed slowly away, backed out of the store, pulled the portal tight behind him. The pharmacist turned away.

"Lock it, Abe. And then call the police. Tell them we want the Medical Examiner, not an ambulance."

"Oi!" His first horror passed, the urchin's dark countenance was alive now with excitement, his eyes dancing. The child of the Ghetto is accustomed to violence, to brutal life and more brutal death. How otherwise could it be when, from the very moment he can toddle, he is put out on the street to relieve for the day the teeming, dark warren which by smug courtesy is called his home?

"Wait." Doc's voice pulled the lad back, "Abe. Do you know this fellow? Did you ever see him before?"

The youngster peered down at the corpse. The man had been tall and thin. Thin not by nature, as the bones painfully visible beneath his drawn, wan skin attested, but because meals had been few and far between for him. The still face, while dirty and unshaven, was not vicious. Weak, perhaps, but not criminal. There was a bruise high on one protruding cheekbone that somehow seemed startling against the pallor surrounding it.

"No, Meester Toiner. No, I ain't seen him nowheres."

"Neither have I," the pharmacist mused. "And between us we know pretty near everyone around Morris Street. Yet..." He checked himself. "Never mind, Abe. Go ahead and make that call."

The boy scampered away, full of importance. This was not the first time he had called the police to the old pharmacy on Morris Street. Somehow excitement, violence and death seemed to swirl around the seemingly somnolent shop.

Doc lifted wearily to his feet. "'The Whisperer'," he muttered under his breath. "Now whom could he have meant by that?"

Still pondering, he plodded to a certain shelf and took down from it a bottle in a blue carton across whose faded face was printed the legend, Nastin's Coughex. He turned, moved slowly to the store's show window, meticulously placed the single bottle in the center of a display of hair-tonic cartons pinned together in weird arabesques. He turned back to the counter, and waited there for the howl of sirens, the bustle of blue uniforms and the half-interested, routine questioning by detectives and by the Medical Examiner—questioning that he knew would lead nowhere.

Curious that he should bother with adjusting a window display while a murdered man sprawled on the floor in a pool of his own blood. And then again it was not so strange. For the placing of that bottle had nothing to do with the business. In fact, if a miracle should occur and someone should ask for a bottle of Nastin's Coughex Doc would be forced to tell him, sadly, that the preparation had been off the market for almost as many years as the old pharmacist had doddered about his store on Morris Street. That blue carton was meant for the eyes of one man, and one alone, Jack Ransom. A broad-shouldered, carrot-topped young fellow whose face was usually daubed with the black grease of his garage mechanic's trade, but whose brown eyes would flash eagerly at sight of that signal, and whose blood would run a bit more hotly in his veins at the prospect of swift action.

And action there was sure to be when Doc Turner summoned Jack with that agreed-upon symbol. For this slight, age-bowed old man was more than druggist to the meek-eyed aliens in this back-eddy of a great city. He was guide to the strange ways of a strange land, cicerone, friend—and protector. Protector against the slimy crooks who prey on the helpless poor. The police? The micks and kikes and wops pay no taxes, have no votes. The police are practical.

And so to the ancient pharmacist, the red-headed garage mechanic, and—Doc's commandments to the contrary notwithstanding—the sharp-faced, dirty-nosed errand boy, fell the task of drawing a deadline around the rabbit-holes of the slum, a deadline that only now and then a furtive criminal dared to pierce.

DOC probed the surface of his prescription counter with an acid-stained

thumb. Up front Abe busily mopped the floor from which the police had finally

taken the body of the stranger, and in the street a stony-faced detective

made futile gestures at questioning close-lipped foreigners who had seen

nothing, nothing at all.

"I'm certain," Doc said to Jack Ransom, "that he came here to warn me against something or someone, and that he was killed to keep that warning from reaching me."

Jack shook his head. "I can't see that. What makes you think he didn't just make a dive for the nearest drug store, after he was knifed?"

"This..." Doc fumbled in a pocket of his alpaca coat, fished something out. "This was clutched in his hand. I got it out and—forgot to show it to the police."

"This" was a rectangular bit of paper, stained yellow not with age but with some liquid that had spilled on it and dried. The stain obscured but did not quite conceal the printing on it, in block letters of red, letters that spelled out:

ANDREW TURNER, PH. G.

Drugs

1401 Morris Street

For External Use Only

Beneath the printing, in Turner's minuscule, neat writing, a further phrase

appeared, the ink blurred and faded.

Jack stared at it. "That's one of your labels, all right." His eyes narrowed with speculation. "But I still don't see... Someone might have been sending him for the stuff, soaked the label off the bottle so they wouldn't have to write the name. He was jumped on the way, knifed..."

Doc turned the label over. Bits of glass adhered to the paper. "No. This wasn't soaked off. The bottle it's from was broken and—"

"Front! Front, Meester Toiner!" Abie called. In their absorption neither of the men had heard the door open and close, nor the tapping of an impatient coin. "Front," Abie called again.

The man at the counter was squat, big-chested. His broad-brimmed hat was pulled down to shadow a low forehead and a knitted wool muffler was wrapped around his neck, had slid up over chin and mouth. It was a frigid January; there was excuse for precaution against the cold—but there was something queerly sinister about the obscurity into which it cast the customer's features.

"Yes, sir," Doc said. "What can I do for you?"

And then his spine prickled with sudden dread. Not at the words of the man's reply, "Gimme some cough drops, will ya? Dat round, red kind." These were certainly innocuous enough. That which tightened the scalp on the old druggist's skull and made his ancient heart skip a beat was the voice in which they came, the hoarse, hissing whisper.

Turner's fingers tightened on the counter edge, till his knuckles whitened. Was this the Whisperer a man had died to warn him against? Was it? Laryngitis is frequent enough, there was no good reason to connect the two. But within him a tocsin of alarm was sounding.

"Trinol Trokeys?" he asked, in an even, steady tone that betrayed his perturbation not at all, while slyly his faded eyes tried to penetrate the shadowy mask the man had contrived. "Is that what you mean?"

The whisper came again. "Yeah. Dat's dem. Trinol Trokeys."

THE man's right hand was thrust deep into a pocket of his overcoat. Why did

it bulge so, as though a snouted muzzle pushed out of the cloth?...

"Jack," Doc called. "Will you bring me out a box of Trinol Trokeys? They're in the bottom left drawer under the prescription counter." With studied carelessness he shoved a display box of manicure implements six inches to the left, to hide a small pyramid of red-edged boxes plainly labeled "Trinol Trokeys." The whisperer gave no sign of noticing, but over his shoulder Turner saw Abe's small head jerk up, saw comprehension come into his face, saw him sidle noiselessly to the door and sidle out.

"That's a bad throat you have. Hadn't you better steam it with Benzoin?"

"Naw. Dis ain't a cold. I always talks like dis." The man looked around, apparently with idle curiosity. "Say!" he exclaimed. "Ain't dat blood de kid wuz mopping up?"

Jack came out through the curtain under the sign, Prescription Department. No Admittance. He shoved a box of Trokeys into Doc's hand, moved out to the front of the store, stood spread-legged and at seeming ease right behind the big-chested man.

"Yes," Turner replied to the customer's question. "Yes."

"Accident?"

"No. Man was stabbed. I couldn't do anything for him."

"Gees! Stabbed!" There was oddly no surprise in the exclamation. "Did the guy say who done it? Did he say anything?"

Doc chanced the flicker of an eye-signal to Ransom. "No, not a thing. He was dead before I got to him." You slipped up there, his thoughts ran. If you didn't know anything about it until now, as you pretend, you wouldn't be so sure the killer wasn't caught in the act.

"Gees," the man husked. "Waddye know." His left hand dropped a quarter on the counter, picked up the carton of cough-drops. "Well, I gotta be moochin' along."

A quick shake of the white-topped head slid Jack out of the man's path. The door slammed behind him. Ransom whirled, started out.

"Wait, Jack," Doc called. "There's no rush."

The younger man turned. "But that's the Whisperer! He came in to find out whether the fellow he killed spilled anything. If I shadow him..."

"That's—being taken care of. Abie will be back after awhile with more information than you can get. The brat's been waiting outside to pick up the trail."

"How'd you get word to him?"

"I didn't. He knew something was up when I asked you for the Trokeys in order to get you out here. So he slipped outside, ready to call for help if there was trouble, or do anything else that occurred to him as proper. And just now I saw him pass with a butcher boy's apron on and a straw hat pulled down over his face. His idea of disguise, I suppose."

"I'll be damned. That youngster sure is a smart little tyke." Jack drummed restless fingers on a counter. "I'd give a lot to know what this is all about. That fellow looked plenty tough."

"Killers are sometimes tough."

"Say, Doc... What was in that bottle? I was trying to read what you wrote on the label you found. I've never heard of lik—lik—"

"Liquid Opodeldoc," Turner put in absently. "It's the Russian name for—Oh Good Lord!"

He twisted, grabbed Jack's arm, dug shaking fingers into hard muscle. "I'm an old fool. Jack, I'm an old fool. I should have thought of that." He threw the youth's arm away from him, wheeled and was dashing back to his sanctum. "Where's my hat and coat? Come on, hurry up. We may be too late."

Ransom hustled after him. "What's up, Doc? For God's sake spill it."

"Wait. No time to talk now. Come on. Hurry!"

AT eleven o'clock Morris Street was still alive with a polyglot mob. But the

alley into which Doc led Jack at a breakneck jog-trot was deserted, and black

shadows clotted thick within it. Overhead, ghostly in the dimness, washed

garments danced on invisible clotheslines, and against an overcast sky aglow

with reflection of the city's sleeplessness the black low roofs of

three-story, backyard tenements showed.

"Phew," Jack muttered. "It stinks back here. Where on earth are you taking me?"

"Hush. They'll hear us. One. Two. Three. This must be it. That's three from the corner, isn't it?"

"Yes. But—"

"Listen."

Sound filtered out of the dark mystery of the house that Doc had pointed out, the faint sob of a violin played by a master hand. It rose to a climax of ethereal beauty, died away. "Thank the good Lord," Doc muttered. "We're in time."

"In time to do what?"

"To prevent the consummation of the greatest crime of our age. Assassinations of monarchs, dictators, are regrettable, of course, but when an artist such as that—"

A whisper cut across his sentence, a husked, hoarse whisper. "Reach, you guys! Grab air!" A footfall thudded behind them. "Quick, before I slit yuh."

Doc's hands went above his head. Jack's followed quickly. On the rubbish-lumped darkness of the broken pavement before them a darker shadow mingled with their own. "I've got half a mind to let you have it anyways." Cold steel touched the back of Doc's neck, pricked. "Dey tol' me you was nosey, didn't have sense enough to tend yer own onions."

"I wasn't aware that vegetable gardening had been added to my other interests," Andrew Turner said, conversationally, into the empty night ahead of him. "But if it were I should uproot them. NOW!"

He barked the last word, ducked forward to his hands and knees. On the instant Jack lashed backward with a slogging heel, caught a shinbone square.

The unexpected blow, launched at the simply disguised command of the old pharmacist, staggered the Whisperer. Jack whirled. Knife-gleam arced at him. His hand darted out. It clutched the descending blade, twisted it, reckless of the searing pain of its edge across his palm, of the quick gush of warm blood. It came free, and the shadowy figure leaped backward with a husked curse, darted away.

Jack plunged after him. Fingers gripped his ankle, brought him thudding down. He rolled, snarling.

"Hush," Doc said. "No noise. Make no noise."

"What's the big idea?" Ransom grunted. He sat up and peered through dimness at the little druggist. "I could have caught him."

"And what would you have done with him if you had?"

"Turned him over to the cops, of course. The sneaking, knifing son of—"

"That's just what I thought. And that's just what I didn't want you to do. A man's life depends on our keeping the police out of this."

The episode had been so swift, so soundless, that the murky silence of the alley had been disturbed not at all. There was only the far-off, conglomerate voice of the urban night to furnish a background for the hushed dialogue. But a peculiar tensity seemed to have taken possession of the malodorous atmosphere, an electric expectancy. Ransom felt it as a tingling of his skin, a pounding in his temple.

"A man's life! You've got me winging, Doc. What...?"

"Not now." Turner scrambled to his feet. "That fellow will be back; he won't give up so easily. We've got to get inside, quickly. Come on."

It was characteristic of Jack Ransom that he rose without another word, without an intimation of the fact that his right hand was gloved with blood, that his palm pulsed with torment. Doc's driving haste was not without reason, he knew—and so he followed the old man at once.

They were two shadows flitting through vagueness, two soundless shadows mounting wooden steps and hesitating at a warped, paint-peeling door. "If it's locked," Doc muttered, "I—" But it wasn't. He slid into blackness and Jack followed. The barrier thudded softly shut behind them.

ABSOLUTE lightlessness engulfed the two prowlers, and the stench that can

only be found in those structures fallen from a once high estate to serve as

shelter for humanity one peg above the utterly homeless. Stench of rotted

wood, of putrescent foodstuffs, of human excrement, of vermin. Jack sensed

his leader's fingers feel for, find, and close tightly about his left wrist,

obeyed the gentle tug that pulled him forward. Dust gritted under his groping

soles, dust and dirt on uncarpeted wood.

"Step," Doc hissed, and the youth lifted his foot to meet it. Then he was climbing through the sightless dark, was crossing a level landing to turn and mount again.

From somewhere above, the melodious strains of the Träumerei welled softly, with an infinite sweetness. Matter-of-fact as the youth was, a nostalgic sadness probed at Jack's brain with fingers of glowing flame. Such music in such—a place! It sang of lonely wandering, of a soul for which there was no rest, no peace in all the world. And yet, somehow, another voice also spoke in the sobbing notes, a voice of unquenchable hope, refusing to acknowledge defeat.

The two slithered across another landing, turned once more to climb another flight. High up, a right-angled thread of yellow marked a door-edge behind which was light. It was from behind that door that the violin sang. A step creaked thinly under Jack's tread.

Startlingly, the song stopped in mid-note. Jack froze, felt Doc's body rigid against his. They were listening, listening intently—to silence. In the sleeping house, from that lighted room, there was utterly no sound.

Yet an aura of startled fear quivered down to them, of crouched, fierce fear listening pallidly, with squeezed heart and breathless lips, for a repetition of that creak. It had been so small a sound, so tiny a disturbance of the night. And yet the master's bow, up there, had halted in mid-stroke; the player was motionless now, so motionless that not even the slither of fabric against fabric relieved the tight silence.

Chill hands stroked Jack's spine. What could a man so greatly dread that a single approaching footstep could paralyze him with nightmare terror?

"Come!" The word was an almost inaudible breath from Doc Turner. "Come on!"

They mounted the last few steps rapidly. Doc's hand on the knob of the door rattled it. A violin string twanged within, snapped, as though a spasm of terror had forced the bow down on it with convulsive force. The door opened; yellow light blinded Jack.

"Bozhe moy!" a fear-thinned voice exclaimed. Then, deeper and more resonant, "Ach Donnerwetter nochmal! It iss the Herr Doktor. I thought—"

"Never mind what you thought, Professor." That was Turner, shutting the door, clicking over its key. "Why is your door unlocked, your room lighted; why are you playing, when you know They are near?"

Jack's sight cleared. He saw a small, bare room; a narrow iron cot, a chair, a rickety table were its only furnishings. Those and books. Books everywhere, on bed, on chair, on table, on window-sill. Poised in the center of the floor, violin and bow in one hand, the other extended, he saw a gaunt-faced man from whose broad shoulders a frock-coat hung in loose, rusty-black folds, and whose massive head was the head of—Moses! Impossible not to think of that patriarch, seeing the great white beard, combed and shining, the high domed brow, the bold nose, the piercing eyes of midnight black.

Fear, that momentarily had eased, now flooded back into those eyes. "They! Near!" Broad, sensitive lips went white as the blanched beard framing them. "No," the ancient groaned. "No! I did not know. Here!" The violin crashed to the floor; great-thewed arms swept up to the ceiling, the beautiful head threw back. "Even here they do not let me rest. How long, oh Lord, how long? How long will you permit the spawn of Beelzebub to persecute your people?"

HE was looking again at Doc Turner, and suddenly there was something almost infantile in the petulant curl of his mouth. "Why do you say I knew They were near? I did not. I did not know."

Turner snapped fingers in exasperation. "Didn't you send someone to me for help? A bum..."

"Ach, nein! A—bum?" A light seemed to burst on the ancient. "Ach! A starving man I had in here to share a meal, a man almost bare in this freezing weather. And in payment he cleaned for me, took rubbish down those stairs it iss so hard for me to climb."

"You fed a starving man when you haven't enough for yourself. How like you! But he paid with more than a little work for that meal, Professor Weinstein. That man gave his life for the food you shared with him."

The professor rocked back on his heels. "His life! Yehovah!"

"That man, Weinstein, was sent to kill you. Your kindness to him frustrated that intention. You spoke of me, perhaps..."

"Yes. Of how you have so many times fought for these poor people..."

"And, not daring to say anything to you, he found the broken bottle of Opodeldoc in the rubbish he cleared from here, came to send me to help you. But his master followed him, and—"

"Alav hashalom. God have mercy on his soul." Weinstein bent his head, as if in prayer.

Doc twisted to Jack. "Ever see anyone like that?" he growled. "I tell him that his life is in danger, that he must move quickly to save it, and he takes time out to pray." He twisted back again. "Leo! You must get out of here. Come!"

Weinstein looked up, and there was no longer fear in his face. "No!" he said heavily, finally. "No!" He put a hand out behind him to the chair, brushed the books from it, let himself down into it, a tired and broken man. "No. I have fled for the last time. I shall wait here."

"Leo! Friend! You have lost your senses. They will kill you."

"Let them. Then I shall rest at last. I am weary, I tell you, weary of these alarms in the night, these shiver-breathed runnings." His somber gaze turned to Jack. "For endless years I have fled. In the night I fled from my beloved Russia because I dared to curse the mad dogs in the palace for that which they did to my people. I found sanctuary in Germany, won to an honored place, and laughed to see the terrible vengeance that overtook those from whom I had fled.

"I laughed too soon. The madness spread to the land of beer and song. Again it was a crime to be one of God's chosen, and again this old tongue of mine blazoned to the world the infamy of the persecutor, and again I must run.

"I came to this free land, this land of promise. They told me the gates were closed to me because of—what is the word?—yes—quotas. But I entered. Skilled by this time in deceit, in the slinking ways of the hunted things, I entered. Crept to this stinking burrow to hide from the police that would send me back to death, to worse than death. Here among the world's downtrodden I thought I had found sanctuary at last."

Jack understood now why Doc had seemed to fear the police as much as he had the Whisperer.

"But the new Pharaoh, the new persecutor, is too small to forget. One had pricked the bubble of his vanity, and that one must not live. So he sent his hireling hounds to hunt me down.

"Now you come to tell me they have found me, they have trailed me down. So be it." The blue-veined hands folded in the patriarch's lap. "I wait for them. Go, friends, and leave me to die."

"No," Doc groaned. "No. Leo. Your heart, your violin..."

He checked, whirled to the door, to the rasp of metal on wood that had sounded suddenly from the door. Wood splintered.

The old boards seemed to collapse. Instantaneously, it seemed, the room was full of masked men! "Get them," a hoarse voice whispered. "Stick them."

KNIVES seemed to flash everywhere. Jack sprang at a stunted figure. His fist

plunked on flesh, and the attacker went down. The youth twisted to a grunt

from Doc. The little druggist had his hands on the throat of one masked man,

but behind him the big-chested Whisperer was lunging with a shining blade

straight at his shoulder-blades. Ransom leaped, flailed at the weapon, struck

it away.

The Whisperer snarled, whipped around to Jack. His foot lashed out, thumped into the youth's groin. Agony shot through him. His knees buckled. He skidded across the floor, writhing. The Whisperer leaped after him, panther-like. The down-sweep of his dagger was a striking snake. The moment stretched to infinity as Jack, unable to move, stared up with horror at the knife-point coming at his throat.

Crash! The Whisperer's head was suddenly obscured by what seemed like shreds of brown wood, was replaced by the white-bearded face of the patriarch, his mouth open, his eyes streaming tears. Incredibly, the knife had not reached the youth's throat. The paralysis of the foul blow he had been struck relaxed. Jack surged erect, saw that the Whisperer was pawing wildly at the violin Weinstein had smashed down on him.

Jack flung a one, two with savage strength into the killer's belly. Those blows had the power of a mule's kick. They lifted the Whisperer from his feet, arced him through the air, pounded him senseless against the wall.

Ransom twisted to a choked scream. The squat man he had knocked down at the start of this mad tussle had come to, was on his knees. His arm was fixed back, his knife lay in the palm of his hand, point backward. It was the gesture of a skilled knife-thrower, and Doc, still struggling with the third of the assailants, was the target.

No earthly power could get Ransom across in time to stop that throw. He started forward—but in that instant he saw the room's single chair slice in a blurred half-circle and pound down on the dagger-hurler's head. The man swayed, collapsed, like a gutted flour-sack, and Professor Weinstein let the chair drop from his hand, stared as if with amazement at his victim. At that moment the purple-visaged man on whose throat Turner's old fingers had fastened a grip of death gurgled, slumped senseless to the floor.

Doc staggered back to the wall, turned a pallid face to survey the shambles of the room. "Leo," he gasped. "Leo. I see you decided not to wait for death." A wry smile twisted his thin lips.

The older man, somehow majestic, fastened smoldering eyes on him. "No," he said heavily. "The blood of the Maccabees runs too hotly in my veins. The blood of the cohorts of Palestine..."

Far below, a door crashed! Pounding feet were like thunder on the worn boards. A whistle shrilled—a police whistle. And Leo Weinstein's face grayed.

"Die Polizei," he gasped. "Bozhe moy! If they come up here they will deport me, and I will be in the power of that—that Herod once more. That will be—worse than death." He stooped swiftly, snatched up a stiletto, lifted it...

But Doc's hand flailed the dagger from the old man. "Fool!" he yelled.

Feet were pounding up the stairs. Someone shouted unintelligibly. The old pharmacist bent, lifted the smallest of the assassins in his arms, reeled out of the door with him.

Ransom was quick on the uptake. His ham-like hands stabbed each to a collar of a prostrate man; then he too was out of the room, out in the darkness of the hall.

Thumping sounds told him that Turner was rolling down the stairs with the man he had hauled out. A flashlight sprayed radiance up through frayed banisters, showed what was apparently a struggling heap on the landing below. Jack tumbled his own captives down the steep descent, shouted, "Damn you! Take that!" He managed to pound a fist into a face with smacking sound.

"Stop that!" a new voice reverberated. "Stop it, or I'll shoot!"

Jack crashed to the lower landing, rolled free of his victims. He blinked into white spotlight glare, made out the blue of uniforms behind it, the glint of brass buttons.

"Ai," an unmistakable nasal voice shrilled. "Ai, Meester Toiner. Jeck. Are you all right? Ai. Deed I breeng eet de bulls in time?"

"THEY jumped at us out of the alley-mouth, Sergeant, had our wallets before

we knew what they were up to and dived back into the dark." Doc was talking

glibly to a florid-faced officer. "We followed them, and they dived into this

house. We caught them on the top landing. That's all there is to it."

"All! By Jupiter, you fellows sure put them through the mill. Wid a couple old guys like you on the force we wouldn't need no guns."

"Here's one wallet, Sarge," a cop interrupted. "It wuz in the little one's pocket. But I can't find the other."

"That's all right. When we get 'em in the back room at the station we'll find where it is."

THE taxi drew up before a patch-windowed tenement. "Out you go, Abe," Doc said.

The little fellow slid to the sidewalk, turned, swaggered a bit. "Good night, Chiff," he piped. "Abie the Boy Detecatiff haveeng brought eet de guardeens of de peace to your rescue, says eet good-night. Deedn't we come at de crooshal moment, hah?"

"Hah is right," Jack Ransom growled. "Hah, hah, hah. You couldn't have picked a more 'crucial moment' to bring the cops. Come here an' I'll kiss you for it."

But Abe already was strutting proudly away...