RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

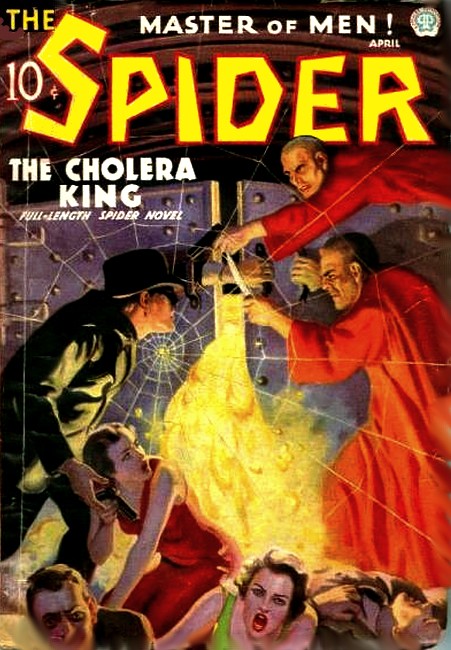

The Spider, April 1936, with "Doc Turner's Doom-Dose"

Doc Turner had mixed many a nasty brew for his ailing wards on Morris Street. Perhaps that's why, when the balance swung between life and love or death and agony, he remembered a chemist's secret to turn the crime-fixed scales...

A FINE drizzle of cold rain had driven Morris Street's usual midnight stragglers to the bleak shelter of their poverty-stricken warrens. The gaunt trestle of the "El" stalked, gray and somehow sinister, over deserted, rubbish-strewn cobbles. On wet-black sidewalks, the wide-spaced glimmer of dim street lamps' luminance was undisturbed...

Andrew Turner, plodding wearily homeward after one more long day in his ancient pharmacy, felt the chill strike through his shabby overcoat to penetrate the marrow of his tired, old bones. Tiny droplets of moisture hung in his bushy white mustache. Stooped, frail, feeble-seeming, he was a lonely shadow slipping through the slum night.

Door-hinges creaked, abruptly, from a high-stooped vestibule between two store-fronts. Light splashed across the concrete just ahead of Turner, and a burly form pounded down the steps.

"Jack!" the old druggist exclaimed. "Jack Ransom! What are you doing here?"

"Doc!" The broad-shouldered youth halted. "You just closed up shop?" Despite the rain, his hat was jauntily askew on his carrot-haired head and, lithely poised on spread, columnar legs, his great body swaggered. "Fine time for a young fellow like you to be getting to bed!"

Turner's faded eyes peered at the scabrous house-number, twinkling with secret amusement. "All right," Turner replied, smiling. "You don't have to answer—but that's where Ann Fawley boards, isn't it?"

"Yeah." Ransom's freckled countenance was split, suddenly, by a sheepish grin. "Yeah. We—we've been to the movies."

"So that's why I haven't seen you lately!" Doc chuckled. "You seem to have found more than a gang of drug-sellers on that last little adventure of ours."

"I found the dearest, sweetest little..." The old man didn't hear the rest of Jack's rhapsody. His thoughts had glimmered away to the past—to a past when rustling elms had lined Morris Street, instead of the smudged, iron pillars of the "El". Ann's grandmother, Madeleine Carstairs, had been the "dearest, sweetest little..." to him, then, her tiny, elfin face enshrined in his heart. A stubborn, tragic misunderstanding had lost her to him for many lonely, dreary years. Only a month before, he had found her again, untouched by the greed and sordid crime that surrounded her, and almost at the moment of that reunion she had died. Mercifully, too, for it was the vile plot of her son and grandson to debauch the children of Morris Street with narcotics that had brought Andrew Turner to her. The old man had been their nemesis, as he had been the nemesis of so many other slinking wolves that attempt to prey upon the helpless poor to whom he was counselor, guardian and friend.

That single glimpse of his lost love had been the old druggist's only reward, that hail and farewell, and the bequest of her granddaughter to watch over. To the stalwart youth who had fought shoulder to shoulder with him that night, who was his right hand in the adventures by which they had drawn about Morris Street a deadline the underworld feared, another reward seemed about to come...

"God bless you, Jack," the old druggist whispered. "Bless you both!" He laid a fragile, almost transparent hand on the other's arm. "And bring you better fortune than I..."

A SCREAM cut across his trembling voice, a muffled scream shrill with terror

and with pain. The two whirled to the sound. It came again, slicing through

the very door out of which Jack had just exited.

"Ann!" The youth blurted. "Ann!" And hurtled away from Doc, making the high stairs in a single leap.

More slowly, but with an agility astounding for one of his years, Turner plunged after him into the flickering dimness of the gas-lighted lobby. Jack's feet pounded heavily on the steps which climbed to fetid obscurity before him, and there was no other sound. Ominously, there was no other sound but that hurried thumping.

Doc pattered up the long, dark ascent. The stench of forgotten meals, of sweaty, unwashed bodies was rank in his nostrils—the foul odor of poverty's abode. A door slammed open, somewhere above.

"Jack!" That was Ann's voice! Thank God it was Ann's voice. "In there. It came from in there!"

Doc reached the landing, and the girl was a slim, fairylike figure in the yellow glow of a doorway, the light behind her a halo-like nimbus in her hair. She was pointing across the narrow space to another paint-peeled door against which Ransom's squat form bulked, tugging at a resisting knob.

"It's—locked!" the youth gasped. "Locked...!"

The rattle of his efforts stopped, was succeeded by a faint, far-off moan. Vague as it was, the sound was compact with anguish, with suffering.

"Get in!" Doc blurted. "We've got to get in."

Jack lurched back from the portal, catapulted against it. His shoulder struck. There was a thud, a splintering crash. The shattered leaf flew open and Ransom pounded through, struggling to regain his balance.

Doc went past him, into darkness which stunk queerly of acids, of acrid, stinging chemicals. He blundered against a wall where the narrow passage curved, veered to follow it. His groping hand touched rough fabric, clutched it. An unseen fist battered the side of his head, pounded him, half-stunned, to his knees. A rectangle of lighter black appearing suddenly ahead of him was blotched by a darker black, shapeless something.

Ransom plunged past Doc. The air that pistoned out of the room ahead was sickly-sweet with the smell of chloroform. A window screeched in its sash...

From Doc's right, a quivering groan sounded, ended in a liquid blub horribly suggestive of blood in a tortured throat.

The old man was on his feet. His eyes, accustomed to the dark now, made out an opening in the wall beside him. He fumbled in his pocket, found matches, struck one. The flame spurted, steadied. Its light flickered through the doorway, glinted in the twisted, macabre glass and porcelain of chemist's paraphernalia. It caught on the verdigrised hook of a gaslight bracket jutting from the wall—just within the entrance.

Doc got his hands up to the chandelier. It popped into luminance which filled the small chamber. Movement under a cluttered table pulled the druggist's gaze down to it—and breath hissed from between his suddenly icy lips.

HIS long years had shown him human agony in many forms, but this...! He

leaped to the table, slashed shut a pet-cock on half-gallon bottle within

which a syrupy liquid swayed. His livid gaze darted among the cluttered array

of containers. He snatched up two of them, was down on his knees alongside

the writhing, cadaverous form whose wrists and ankles were lashed to the

table's four legs. The man's shirt was torn open. On his naked chest, where

the contents of that bottle had dripped through a slashed hole in the

tabletop, fierce blisters splotched the quivering skin, blisters whose edges

were white but whose centers were already black with the char of flesh burned

by sulphuric acid.

Ammonia-smell reeked in the air as Doc spilled the contents of one of his bottles on those ghastly weals. Oil gushed from the other in a pitiable attempt to soothe those terrible burns.

"No use!" It was a mere flutter of sound. "Listen..."

The breathed words jerked Turner's attention to the man's contorted features, to the hollow, sunken cheeks a straggly gray beard did not mask—to the blue lips writhing in agony. There was recognition in the pain-darkened eyes staring at him, agonized appeal.

"Daphne!" It was evident that the tortured man's soul hesitated only to husk that name. "Take care...!" And then: "Under third board. Add sodium hypochlorite. Five point two grams. All... to Daphne. Will you...?"

"Yes, Eufrastes. Of course I will take care of Daphne. Of course...!"

Doc didn't say any more. If he had, the man would not have heard it. He would never hear anything more in this world.

"He got away, Doc!" Jack's voice rasped. Ann was a wide-eyed, small figure beside him. "He got down the fire-escape and... What the Hell?"

"Hell is right." Turner came wearily erect. "A fiend from Hell tortured him to death."

"Tortured...? What for? There isn't a stick of furniture in the place except what's in here and a big bed inside. What did he have...?"

"He had something, a formula of some kind." The pharmacist was piecing out the dead man's last words with a few guarded hints he had dropped while purchasing chemicals in the store on Morris Street. "It's hidden somewhere in here. But where's Daphne? Where's his little daughter?"

"I—I didn't see anyone..."

"Where's that bed you spoke of?"

"In there. Near the fire-escape window."

Doc recalled the odor of chloroform, and his heart sank. "Come on! She must be..."

They pounded down the hall to that other room. A match crackled again, and grimy radiance spilled down on a huge, tousled bed. Spilled radiance on a wee, pale face, whiter than the pillow against which it lay, and on a drenched rag that seemingly had been tossed to one side by some movement of the unconscious little girl.

OLD Doc Turner's fingertips found a tiny wrist beneath the sheets. Something

of the bleakness went out of his countenance. "She's all right. She'll come

out of it."

"Oh, the poor little thing!" Ann brushed him aside, had the tiny form in her arms. "The poor little dear!" she crooned.

The old man's countenance softened as he looked at the picture they made. If he'd ever had a daughter... "I promised her father I would take care of the child."

"We'll take care of her. She'll live with me and be my little sister."

"I hoped you would say that. Take her inside with you now, while she's still asleep. The Lord knows it's going to be bad enough for her without her having to see her father as he is."

Ann carried her out. Daphne Papalos was eight, but she was small-boned for her age, and privation made her a pathetically light burden. Doc watched them go, turned to Jack.

"The robber chloroformed her as he came through, so that she wouldn't give the alarm. I'm surprised he didn't kill her."

"We'd better notify the police, hadn't we?"

"Not yet. Not till we uncover his formula. After they get here, we won't be able to without being observed, and even though he told me about a change in it without which it is apparently worthless, there would be a lot of red tape about selling it. I know that he thought it was extremely valuable, and Eufrastes Papalos was too good a chemist to be mistaken. He was head of the biggest chemical works in Greece, but he made the mistake of getting mixed up in the politics of that turbulent country. When his party was proscribed, he barely escaped with his life. His wife died from exposure, and little Daphne almost followed her. The kid's gone through a lot, and the best in life will be none too good to make it up for her."

"That's right, Doc. I..." Abruptly Jack leaped from his stance at the door, diving for the still-open window. He was out through it. Doc saw his bulky shadow move across the fire escape, got to the window...

Beyond that platform was a ten-foot space of sheer vacancy, and then a low, black roof covering the rear extension of a store next door. A figure flitted across the glistening tar, disappeared over the further cornice...

"The rat jumped across," Jack grunted, climbing back into the room. "My heel caught between two slats and I couldn't get loose till it was too late."

"He came back to listen," Doc gritted. "But what good would that do him? I don't understand..."

Minutes later he did understand. For, having figured out that Papalos' cryptic 'under the third board' signified a recess in the floor, the two had found a loose board near the further wall of the laboratory, under the window of that small room. A loose board and—nothing beneath it!

The old man stared at the empty niche, slit-eyed. "Gone! He's been spying on Papalos, knew just where to look for it. Maybe he got hold of it long ago, tried it out. Discovered it wouldn't work and tortured the Greek to find out what was wrong. He's got the formula, but I've got the way to make it work. Neither of us can do anything about it."

"I wonder," Jack pushed through tight lips. "I wonder..."

"What do you mean?"

"He's got the formula. And he knows you have the rest of the secret. He heard you say so. I've got a hunch he'll be coming after it."

"Let him come." The old man was very grim. "Let him come. That's just what I want!"

THE torture-death of Eufrastes Papalos served to enliven the drab monotony of

slum life for a day or two, and then a raid on pinball games in the scabrous

corner candy stores replaced it on polyglot, chattering tongues. By Saturday

night the surging pushcart peddlers and marketers had forgotten it. But

black-eyed, black-haired little Daphne still wakened trembling, at night, to

cling to the warm, tender presence of her new Mamma Ann and be kissed to

sleep with whispered assurances that Papa was happy in the faraway land to

which he had gone.

And in the drugstore on Morris Street, a sober-faced old man still scrutinized, through a peephole in the prescription-room partition, every new customer clumping in. A new note seemed to sound in the familiar turmoil of the street—a sinister, warning note like the hiss of a poisonous snake. The killer who had dared to creep back to the scene of his crime to eavesdrop on those who had flushed him from his prey was not one to give up the fruits of his crime so easily. His very inactivity was ominous. When he struck...

A telephone-bell clamored its shrill summons from the booth near the door. "Answer it, Abe," Doc commanded, impatiently. "See who it is."

"Shoor, Meester Toiner." The undersized, swarthy errand-boy wiped his hands on a grimy towel. "Maybe eet's a message fahr me to go out und a two cents teep to get, hah!"

"Maybe."

But Abie's hopes were doomed to disappointment. "Eet's fahr you," he called. "Somevun vants to talk to you."

Queerly, a premonition of disaster was a leaden weight at the pit of Doc's stomach as he thrust through the curtained archway leading to the front of the store and hurried between the cluttered, dusty showcases to the booth. So seldom was there a phone call for him...! "Hello!"

And then Ann's voice was in his ear, taut, thin with distress, with fear. "Mr. Turner! Daphne's gone! I can't find her anywhere. I can't...!"

"Wait!" His pulse might pound in his wrists, a dark flood of consternation might seethe through his veins, but Doc's voice was steady, low. "Wait. Tell me where you are and what's happened."

"I'm in a booth in a cigar store on Hogbund Place. I took Daphne to a Shirley Temple picture. The lobby was crowded when we came out. I lost hold of her hand. And then—and then I couldn't find her. She wasn't around anywhere!"

"She's probably gone home. Have you...?"

"No. I haven't. I didn't think of... Ohhhh!"

"Ann! What...?"

Her whisper quivered with terror. "There's someone standing against the door of the booth. He's got a gun in his hand, in front of him so that it can't be seen by the people in the store. His face! Like a death-mask... He's opening the booth-door..." She cut off. But there was another voice in the receiver, a toneless ghastly rasp.

"Doctor Turner? I have the little girl and the young lady is going along with me." The crisp, precise enunciation of an educated alien, redolent with threat. "In fifteen minutes there will be a taxicab outside your store. It will bring you to us. If you do not come, or if there is any hint of suspicion that the cab is followed, I will—not kill them. No. But they will wish themselves dead when I am through with them. You believe me, do you not? You have seen what I can do?"

A CLICK, and the hum of a dead wire. Doc stared at the blank wall of the

booth. Faces formed there. A pinched, hunger-pallid little face with black

eyes and blacker hair. Another—delicate, yearning him to it with the

elfin sweetness that long ago he had loved and lost and miraculously had been

restored to him. The horror of an acid-blistered chest dropped across those

faces like a veil, and they were shuddersome, ghastly masks out of which

tortured despair stared.

The telephone receiver went back into its hook so gently that the vulcanite made no sound at all against the metal. But Doc Turner stumbled a bit, going out of the booth, as though he were suddenly half-blind.

"Abe!" His call was low-voiced, almost tender. "Abie, my son!"

"Vot ees, Meester Toiner?"

"I have to go somewhere in a little while. A taxicab is coming for me. Lock up after I leave, but don't get any bright ideas about following it. Do you understand? You—must not—try to follow that cab."

There was a gray film under the urchin's grimy complexion. Too often had he made an invaluable third in the forays of Doc and Jack not to comprehend that his beloved employer was going into deadly peril, and going alone.

"Vot time shall I come een tomorrow morning?" It was an expression of utter faith in the old druggist, of confidence that no matter what were the odds against him, Doc Turner would win through.

"The same as always. I'll be here—perhaps."

That "perhaps" was not like Andrew Turner. This was not similar to his usual expeditions against the forces of criminal greed. This time his heart was involved, and for the first time he was afraid. Deathly afraid, but not for himself.

An automobile horn blared through the raucous tumult of a Morris Street Saturday night.

The cab windows were small, and they were so smeared with spatters of mud that Doc could not see through them. The vehicle's interior was close, stuffy. Turner reached for a window handle to let some air in.

It turned in his hand, freely. Too freely! It was disconnected from its gears and the glass above it did not move. A tiny hissing underlay the chattering rumble of the motor. The mustiness was threaded by a tendril of alien odor, sweet, sickly sweet. Doc's thin lips jerked once with comprehension, and he shoved himself back into the seat leather, got a thin arm through a door strap. An unexpected lurch of the car might otherwise throw him to its floor, might break his bones, brittle as age had made them.

The chloroform smell grew stronger. Flicking lights projected the driver's shadow on the translucent window across the cab front. It was the shadow of a crouching, gigantic raven, its predatory beak hooked to tear at the vitals of its prey. It blurred, and a faint nausea twisted at the pit of the old man's stomach. He swayed against the cab-side as the car turned a corner.

The last thing of which he was conscious was the trailing thought, "He isn't taking any chance of my being able to retrace the way I'm being taken. He's careful. Too careful..."

VERTIGO swirled in the weltering blackness of oblivion. The darkness was a

great wave that lifted him on its bosom. But the smell of it was the

familiar, pungent aroma of a chemical laboratory permeated by a dank, earthy

odor as of a cellar far underground.

A child whimpered somewhere. An acrid liquid stung the back of Doc Turner's throat. He gagged, swallowed convulsively. The fumes of the chloroform retreated from his brain, and his eyes opened.

A face hung in the dimness above him. The green-gray face of a ghoul, its lustrous, parchment-like skin drawn tight so as to mold the skull beneath into ghastly reality. Eyes like emerald coals burned gloweringly out of their deep-sunk sockets.

The mists cleared, and Andrew Turner knew that he was lashed hand and foot; that he was lying on the damp, concrete floor of a wood-ceilinged, wood-walled basement, and that it was a ferret-visaged, raven-beaked man who bent above him.

"Come awake, eh?" a crackling, sere voice said, though the tight gash that served his captor for lips seemed not to move at all. "About time!"

"Yes. I'm awake."

A gurgle pulled Doc's look sidewise—to the slender frame of Ann Fawley, lashed to a time-darkened oak upright, her horror-black eyes staring at him over a white tape that gagged her. Alongside her, bound to the same splinter-surfaced column, was Daphne Papalos. The child hung limp from her bonds, and against the ebony screen of her trailing hair her skin was sallow-white, waxen almost with the sheen of death.

The old man jerked upward to sitting position, despite the restraint of his bonds. "What have you done to them?" he gusted. "What...?"

"Nothing—yet." The fellow's thin mouth writhed to an evil leer. "What I do to them rests wholly with you."

"What do you mean?"

The man moved aside, gestured. Near the further end of the cellar was a slab-topped, sturdy laboratory table. On it, Doc saw a profuse collection of retorts, beakers, mortars; a scale; certain powders weighed out on white, paper squares. Shelves gridded the wall behind, shelves on which were ranged bottle after bottle of vari-colored chemicals, liquid and solid.

"Have you ever seen what pure chromic acid will do to human skin?" The question dripped slowly, meaningfully, to Doc's hearing. "Or caustic soda in concentrated solution? I have. But there's one thing I haven't tried yet, and I'm very anxious to. Hydrofluoric acid inserted drop by drop, under a woman's eyelids. It makes glass opaque. I wonder what it would do to the transparent membrane of the cornea?"

"You wouldn't dare!" The exclamation was wrenched from Turner by horror. "You wouldn't..."

Again that mirthless laugh. It was made by an inspiration of the man's breath, rather than an exhalation. Light-worms crawled deep in the viridescent depths of his strange orbs. Doc Turner could not control the shudder that passed through his feeble frame as he realized that he was in a madman's power. He and Ann and little Daphne. A sadistic madman in whom only rapacious avarice could overwhelm the lust for ingenious, demoniac cruelty.

And then he was again cold, and calm and even-voiced. "All right," he murmured. "I am convinced. If I tell you what you want to know, you will let us go?

THERE was disappointment on that spectral countenance. "I will not torture

them—or you. You have my word."

The form of that response confirmed the old druggist's fears. Laros would not free them. Insane, he was, but he knew that he would not be able to sell the formula if he released them.

"Very well. What Papalos told me was—" He hesitated, appeared to be cudgeling his memory. But he was really wondering how much of a chemist Laros was. There was a certain awkwardness in the way apparatus was set up.

"Well? What are you stopping for?" The man's foul breath blew in Doc's face as he thrust his spectral countenance closer to him. "What did the old fool say?"

Turner made his decision. "Add twenty grams of potassium chlorate and mix it thoroughly with the carbo-ligni before you add the other ingredients. Thoroughly, or the reaction won't work."

Laros' bony fingers knotted at his sides, fell open again. "It had better work," he lipped. "Or..."

"I'm not trying to fool you." Doc's glance shifted under the livid scrutiny that was bent upon him, fled guiltily from those eyes.

The corners of the man's mouth twisted. "You can't," the slow, threatening response came. "Because I'm going to mix the compound now. And if you've got a God you'd better pray to Him that it will answer the tests."

Andrew Turner did pray, as Laros moved away from him. And as those skinny fingers lifted down a wide-mouthed bottle from the shelves, he knew that his prayer was answered. For the potassium chlorate spilling out of that bottle onto the scale pan was in large, white crystals. In crystals...!

The brittle silence which shut down in that alchemist's den was broken only by the crisp rustle of those crystals sliding from the weighing paper into a large mortar. Laros lifted another paper from that table, slid its burden of dull-black powder into the mortar, stirred the mixture with a glass rod. Then he had snatched up a heavy pestle, poised it over the round basin of heavy stone to powder the crystals, hesitated...

Doc's breath caught in his throat. Had the madman thought of something at the last moment? Of that something he had prayed he did not know?

The pestle pounded down. A thunderous explosion crashed out of the mortar. A whirlpool of flame seethed out of it, enveloped Laros' head, sprayed upward to the ceiling. Bottles smashed, a shelf crashed down.

And then a shriek sliced from the reverberation of the explosion, a shrill eldritch scream of utter anguish. The gaunt form of the torturer pounded down into the shambles of splintered glass and smoking acids. It writhed, tossed over. Fingers clawed at a countenance which was no longer a face but a blood-smeared, blackened, eyeless false-face that sent cold shivers of revulsion through the old druggist. The tormented body arched, slammed down again. Quivered... and was still...

THE pure hysteria of relief, of despaired-of triumph, jabbered thin syllables

from Doc's icy lips. "It worked, Ann! He didn't know a mixture of charcoal

and potassium chlorate was explosive. I saw the charcoal on the table there,

took a chance that it was included in the formula. It's killed him, and we're

all right now. Ann dear—we're all right!"

A gurgle from behind the girl's gagged mouth silenced him. A gurgle, and terror in her eyes. He jerked around again, following that frightened gaze.

Curling tendrils of smoke met his glance, and the flicker of a darting flame-tongue from the ceiling. The explosion had worked only too well. Not only had it killed Laros, but it had set fire to the dry wood of the hidden laboratory.

It was roaring, like a beast let loose. The ceiling was aflame, and flames ran along the wall, licked at the table. Behind the bound figures of Ann and Daphne the glare showed Doc a door. Maybe he could reach it. Maybe he could roll to it, fumble it open and get out. But by the time he could get help the girls would be beyond the need of help.

Doc started to roll. Not towards the door, but towards the other end of the cellar, where the flames glared fiercest through the black clouds of smoke, where the heat of the flames was a blast of Hell.

An orange-red snake ran out to meet him, serpentine flame lashing out to greet him. Doc lay on his back and lifted his bound hands to grasp that torrid streamlet of death.

The fire licked around his wrists. Agony needled them, darted unendurably up his arms, ringed his chest. A scream of agony wrenched from his throat. But the rope about his wrists smouldered, burst into flame. The rope parted.

He was on his feet. Somehow, there was a jagged piece of broken glass in his fingers and he was staggering through smoke-blackness; sightless, as if in the uttermost depths of Avernus; in blackness as lurid as the seventh pit of Hades. Where was Ann?

He thudded against wood hot as the skillet upon which fry the souls of the damned. Against wood that was a wall. He had missed the beam to which the girls were bound. He had missed it!

"Ann!" he yelled. "Ann! Where are you? In God's name, where are you?"

Fool! She couldn't answer. How could she answer him, gagged as she was? His scrabbling fingers found a doorknob, the knob of the door that would let him out of this furnace. He pulled it open.

"Ann," he yelled again. "Ann!"

THE flames roared wild laughter at him. The fire mocked him. And somewhere

there was another sound. Pud. Pud. A dull thump, far off, infinitely

far off. Somehow she was managing to make that noise. Somehow she was

pounding her heels against the beam to which she was lashed.

Doc Turner pushed himself away from the door that offered escape. Pushed himself away and reeled back into the seething maelstrom of smoke-laden death. Soft bodies stopped him. Ann and Daphne.

His shaking fingers felt for and found the ropes that bound them to that pillar. The keen-edged shard sliced at those ropes, sliced at them. Suddenly there were hands helping him, slim, cool hands.

A small body was in his arms, and a hand was on his shoulder, and he was moving again. Moving with the current of smoke, of flame, that seethed through the door he had opened.

Doc staggered, toppled to painful knees. He was crawling. He must keep crawling though every move was an agony, every slow inch a conquest of raging death itself. Someone was crawling alongside him, he was dimly aware, and something rested across his shoulder. It was heavy.

The smoke was thinner. It still burned his lungs but it was thinner. His knuckles thumped against stairs. His hand lifted.

He could—go no further. He was spent. "Ann!" his voice said. "Ann. Take Daphne. Maybe you—can get out."

He wanted to sleep. But the hands wouldn't let him. The hands were pulling at him, were dragging him. Up. Up.

Doc came out of oblivion to realize people were puffing all around him and he lay on something rubber—he was out in the street. "Ann!" he muttered. "Daphne?"

"They're all right, Doc." How had Jack come here? "They're all right, thanks to you. They've been taken to the hospital, but they'll be all right. And you're going there, too. You've got to go there, you know, to rest for a while."

DOC was like a white mummy, swathed as he was in bandages on that hospital

bed, but he managed to smile through the slits that had been left for his

eyes. To smile at Ann, with only a gauze-covered burn on one cheek as

reminder of what might have been, and tears of happiness in her tawny

eyes.

"Daphne wasn't even burned as much as this," she said. "And she's doing so well in school that I'm quite proud of her. But Morris Street misses you, Dad Turner. You must come back to us soon. We need you."

"Need me! You must not have anything more to do with me. I'm dangerous. I create danger for everyone around me.

"That's enough out of you. I won't permit you to say anything like that. You just keep quiet while I tell you all about what's going on."

"All right, boss." Doc's tired eyes closed, to hide the happiness that glowed in them. It had been so long since a soft, feminine voice had given him orders. So very long...