RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

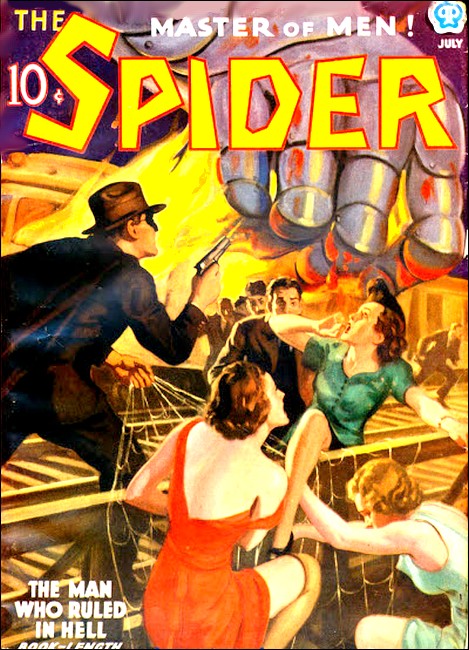

The Spider, July 1937, with "Doc Turner—Slave Buyer"

In a prison tenement on Morris Street, a slave-whip cracked, lashing human souls down the road of misery and despair! And Doc Turner, kindly grey defender of the oppressed, walked into death's dark alley to save those souls from their living hell!

DOC TURNER halted abruptly. His head turned, slowly, toward the black mouth of the alley out of which had come a rustle of newspapers, and then a low sob, instantly hushed.

The tenement-lined street was a desolate ravine, its darkness relieved only by the glimmer of street lamps whose light struggled wearily to penetrate the river fog. The hoot of a lonely ferry came to Doc, deep and melancholy against the distant growl of the never-sleeping city, but on Morris Street the brooding silence was broken now only by the sound of breathing; the old man's own breathing and the intermittent faint whisper of another's.

Turner's frail and feeble-seeming form was the only occupant of the night-bound sidewalk. In the wee hours between midnight and dawn even the teeming slum sleeps; the raucous cries of its push-cart hucksters, the cries of its tattered children, the polyglot chatter of its alien denizens all stilled by weariness. Even the thin whine of ailing babes cannot go on forever.

Doc's faded blue eyes peered out from under the eaves of his beetling white brows, probing the murky slit between two high walls of weather-stained brick. No cat, no draggled canine, had ever sobbed like that. A human must lie within those shadows, a human in trouble.

The muffled sound came again, breaking irresistibly through a throat tightened to throttle it. He moved toward it.

Within the alley the garbage-smell was foul in Andrew Turner's flaring nostrils. He wiped the fog's wet from his drooping white mustache with a gnarled hand whose sensitive fingers were stained by the medicines he had compounded and dispensed here on Morris Street for more years than he cared to count. Something pale showed in the black. He stooped to it.

His reaching hand touched paper, felt beneath it a small frame of bones. A squeal of pure terror came out of the pallid shadow. The form Doc had touched squirmed away, then sprang upward with a crisp rustle of the newspapers that had covered it.

The old man clutched a jerking arm whose muscles were flabby along pipe-stem bone with no flesh to pad it. A small fist batted ineffectually at Turner's side.

"Lemme go!" his captive gasped. "Lemme..." and broke into another sob.

"You've nothing to be afraid of, son," Doc said evenly. "I'm not a cop." In the dim haze of luminance seeping into the alley he made out that he had hold of a scrawny little boy, the strained-back head barely higher than his own waist.

"It ain't the cops I'm scared of. She's worse than the cops. She's..." Terror shrilled once more into the youngster's voice. "Don't make me go back there. Don't... I'll kill myself. I swear I'll kill myself if you take me back to her!"

"I won't take you back to her." If there had been light enough the lad would have seen two white spots pit Turner's age-seamed cheeks at the corners of his great nose and his face grow bleak and ominous. "I won't make you do anything you don't want to do."

ANDREW TURNER was far more than a pharmacist. Pottering

about his dingy drugstore, he was guide, cicerone, friend to the

bewildered aliens of Morris Street. More even than friend. He

could metamorphose into a very avatar of vengeance, an

indomitable and inescapable avenger, if the occasion offered

itself.

But relentless as Doc always was when his people were injured, when it was their children, their little, helpless children, who were wronged a fiercer wrath blazed within him, a flame white and terrible. There was no peace for him then, no rest, till that flame had destroyed those who had aroused it.

It was hot within him now, but nothing of it showed in his soft tones. "What's your name, sonny?"

"Ted," the boy mumbled. His thin little body still quivered, but he was no longer trying to tear himself away. The old man's gentleness, the tenderness that was an almost tangible warm aura about him, were having their effect.

"Ted what? What's your last name?"

"Haven't any."

"You mean you don't want to tell me?"

"Naw. I mean I haven't any last name. That's all there is, there isn't any more."

"All right then, Ted it is. You're cold and wet, aren't you Ted? And hungry?"

"Hungry?" The word was a moan. But the boy stiffened, and said; "Naw, I ain't hungry. I ain't cold either. Newspapers keep you nice and warm when you cover yourself up with them good."

"Well, if you're not hungry, I am. I'm Andrew Turner, the druggist on the corner, Ted. I was working late tonight. I just closed up and I'm going to stop in Persky's Lunchroom, for my supper. Persky makes the best steak in the city, an inch thick and oozing juice, and so tender it melts in your mouth. Only trouble is his portions are too big for an old man to eat, and I hate to waste half of the steak after I've paid for it. How about coming along and helping me out?"

"Does he give you French fried potatoes with it?"

"Sure he does. They're golden-brown and crisp and just hot enough. And he smothers the steak with onions too, oodles of them. My mouth's watering now, thinking of the way they smell."

"Gee!" Volumes of longing were compressed in that monosyllable. "Gosh!"

"It's a shame to leave half of all that on the plate. Come along, son, and take care of it for me. How about it?"

"I—I—" the youngster gulped. "No. I can't. I don't dare."

"You don't dare?" Doc had let go of Ted's arm.

"Somebody might see me and tell her about it. She might come for me, and..." The boy broke off, but those last few words of his had been husked by a fear too great for such a child.

Doc slapped a fist into the palm of his hand. "I've got it!" he exclaimed. "I hate eating in that lunchroom but it's too lonesome in my room. Nobody will see you come there with me. Here. I'll give you the key and tell you just how to get to it, and I'll bring the stuff in from Persky's and we'll have a midnight picnic. How's that, Ted? Don't you think that will be fun? You can't say no."

He did not. His resistance was at an end.

THE room where Andrew Turner spent the few hours he

spared from his drugstore was small and bare; its furnishings

only a double bed, a table, two chairs and a shelf of books; but

it had its own small bathroom which the druggist had had

installed.

Ted, stripped to his tattered, mud-encrusted trousers, was scrubbing furiously at his face and arms. Sliding out of his own coat and arranging the viands on the table, Doc's countenance grayed as with covert glances he saw how tightly the skin was drawn over the boy's gaunt ribs; the torso so emaciated that Ted's head seemed far too large for it; the belly pinched, the back bruised by long yellow and blue and black weals.

The lad could not be more than ten, even if privation and suffering had given him an old man's face. As that face emerged from behind a vigorous towel, Turner saw that though it was sharp-chinned and sunken-cheeked an almost ethereal spiritual quality dwelt in its white, transparent-seeming complexion, in its great, dark eyes.

"Here," Doc said. "Slip on this pajama coat while you eat." The lad saw the steaming table. His tongue licked his cracked lips. "Oh, gosh!"

Starved as he was, the waif managed to display a surprising amount of good manners. Doc watched him, intrigued by the small vagrant's incongruous refinement, but said nothing at all till Ted slumped back in his chair, replete at last.

"Gosh," he muttered, "that was good. Thanks."

"You're quite welcome," the druggist replied, gravely. "It was good, wasn't it? You managed to do away with plenty even if you weren't hungry."

"Not hungry! After living out of garbage cans for three days! I..." Ted checked himself, pushed hands down on the table and lifted himself from his seat. "I got to get dressed now and go."

"You're not going yet. You're sleeping here with me."

"I'm not. I can't." Ted darted back to the little bathroom, picked up the ragged jacket that seemed to have been his only covering above the waist. "Maybe my chance will come this morning. I mustn't miss it." Something dropped out of the rags, clanged metallically on the tile floor. The boy bent swiftly.

"Your chance for what?" Doc had not moved from his chair.

"For this!" The lad came erect. There was a knife in his hand, a hiltless and rusty blade sharpened to the wicked slimness of a stiletto. "To stick this into her. Maybe she'll forget to lock the door this morning, when she comes back from marketing." There was no refinement in his face now. It was snarling, the eyes wolfish.

Still the old man did not move. "You can't get away with that, Ted." He might have been talking about the weather, the way he said it. "You're sure to be caught. Caught and punished for murder."

"I don't care," Ted snapped back. "Let them catch me, after I've done it. She'll be dead then. She won't be able to whip the kids like this," his hand flicked to an unhealed scar across his abdomen, "any more. They'll be free. Ruthie'll be free. They can do anything they like to me, after that."

"This 'she' you hate must be pretty awful, Ted. Tell me more about her. Tell me who she is."

"Like Kelly I will. You'll warn her. You'll tell her I didn't drown in the river, like she thought when they found my clothes on the pier after I got away. You'll tell her I'm coming after her."

"Do you think I will, Ted? Look at me. Do you think I would give you away? Look in my eyes before you answer. Read what they say."

The lad's dark eyes found Doc's bleared blue ones, were held by them. The two, the white-haired old man and the chestnut-headed small boy, were very still, in the center of a brittle silence.

"No," Ted sighed at last. "You wouldn't peach on me. But you can't help me."

"Perhaps I can."

"You'd only go and tell the cops, and she'd fool them like she always does, and when they go away she'll be mad and give the kids an extra licking with that snake-whip of hers."

"I promise you I won't tell the police anything. I promise you that if you tell me all about 'her' and the kids, and I can't figure out a way to help them and to punish 'her' for what she's doing to them, without repeating what you say to anyone else at all, I'll let you go out of that door and forget that I ever saw you. You believe me, Ted, don't you?"

"Yes."

"Then start talking."

DAY begins early in the slums. Factory whistles blow at seven, at

seven ditch diggers must be ready to spade their first shovelful

of earth, to strike their first pickaxe blow, and so Morris

Street and its environs come wide awake at six.

But at five in the morning, there was no one to see a white-haired, shabby-coated man and a small boy whose mud-encrusted tattered jacket flapped open to show that he wore nothing beneath it, turn the corner from Hogbund Lane into Pleasant Avenue.

They turned in at one crumbling stoop, climbed it, vanished within the vestibule at its head. Inside, they mounted the worn, uncarpeted stairs dimly illuminated by pin-point gas jets at every second landing.

The oddly assorted couple reached the third landing and paused at a door from which the paint flaked. Doc looked at the boy inquiringly. Ted nodded. The druggist's knuckles rapped sharply on the scabrous panel.

Strangely enough at this early hour there was instant response from within.

A key rattled in the door lock, turning over. Ted slipped behind Doc and the old man could feel him shiver. The portal swung inward, and the space where it had been was filled by a monstrous figure.

It was a great, bulging mass of dough-like flesh enveloped by a grey, musty-smelling Mother Hubbard apron. The face, double-chinned, pendulous-cheeked, was a shade lighter grey. The straggling, uncombed hair was a shade darker with dirt. Tiny, red-rimmed eyes peered at Doc, and bluish lips parted to show yellow, rotted teeth.

"Well?" The mushy voice seemed to come from somewhere in the region of the woman's un-corseted breast-pillows.

"You're Mrs. Tintel, aren't you? 'Aunt' Eve Tintel?"

"I'm Eva Tintel."

"You board children here? The children of widowers who cannot take care of them, and the children of—mothers who have no legal right to be mothers?"

"Yes, if you call it boardin'. I call it runnin' a charity home. Their folks pay me one or two months and that's the last I hear of them, but by that time I'm in love with the little dears and I can't send them away to an asylum."

"One of your boys ran away during the week? A little chap called Ted?"

"He didn't run away. He went swimming in the river, against my stric' orders, an' he drowned. Poor lad. I been heartbroken ever since."

"He was not drowned," Doc said. "Here he is." He pulled Ted around in front of him, shoved the boy at the sniveling woman.

"Ted!" the woman screamed, folding the lad in her enormous arms. "Ted, you bad boy! I've wept my eyes out over you and all the time you were alive. You ran away and... Thanks, mister," she interrupted herself, "fer your trouble bringin' him home. I won't keep you no longer." She started to shut the door.

SOMEHOW Doc was across the threshold, so that the wooden leaf hit

his shoulder, and stayed open. "It wasn't any trouble," he said.

"It was a pleasure. I rather like the lad. I'm all alone in the

world. I thought I might take him off your hands, adopt him, if

you're willing."

"Adopt..." Mrs. Tintel looked at him speculatively. "No, I don't think I'd like to lose him. Ted's a wild lad, but I missed him so terribly while he was gone that I can't stand the thought of parting with him, now that he's come back to me from the grave like. An' I don't think Teddie would want to leave me. Would you, Ted?"

"Huh?"

"Don't you love your Aunt Eva too much to leave her?" There was a sibilance in her spongy accents now, a warning, reptilian hiss.

"Yeah."

"An' besides, there's six years board owed for him. Six years the trollop that left him with me hasn't sent a cent for his keep."

Doc managed to conceal the blaze of indignation that leaped hotly within him at the epithet. "I might be willing to pay you that," he said evenly. "How much is it?"

Eva Tintel was very much interested now. "Six years at five dollars a week. Let's see, that's—that's—five times fifty-two times six... Come in, mister and I'll get a paper an' pencil an' figger it out. There's the clothes too, that I bought him, an' all the toys. He's cost me a fortune, an' now when he's just gettin' old enough to maybe pay some of it back by sellin' noospapers or somethin' you want to take him away from me. Come in." Eager as she had been to get rid of him, she was now just as eager to keep Doc Turner from going. "Come in and have a cup of tea while we talk about it. Mebbe I won't charge you for the clothes…"

The room was the kitchen of the flat. A tremendous coal range made it almost unbearably hot, although there was only a large steaming kettle on it, and a frying pan that seemed lost on the great black surface. The sink was piled high with dishes, and there was a soap box in front of it. There was a big table, cleared, about which Doc counted ten small chairs and a tremendous armchair that stood at its head.

In the wall beside the stove there was another door, and that was closed. A key stuck out of its lock.

"Ted, darlin'," the woman said. "You get a pencil and paper off the cupboard there and do the sum while I get the gentleman his tea. Mind you do it right too, like I taught you. Six times fifty-two, times five." She waddled to the stove and reached for the kettle.

"Here's the cups, mum," Ted said, bringing them, rattling, from the cupboard where he had gone for the writing materials. "Your big mug and a little one for Mr. Turner. I've spilled the essence in."

EVA TINTEL brought sugar and spoons, settled ponderously into the

chair that obviously had been reinforced to support her weight.

"Sit down, mister," she said. Doc obeyed. "Now, tell me would it

be a good home you can give my dear little Ted?"

"Not as good as this," Doc said gravely, spooning sugar into his tea, "but then I think Ted is of the age where he needs a man's guiding hand. You are a widow?"

"A lone widow," the obese female sighed. She buried her face in her mug. "Trying to make a living by takin' care of a few unfortunate babes," she took time out to continue. "An' a mighty poor livin' it is."

"How many have you here?"

"Five little girls and four boys, not countin' Ted. All asleep inside like little angels, while their Aunt Eva is on her feet already, gettin' breakfast ready for them."

"Asleep?" Doc kept his eyes resolutely away from the dishes piled in the sink. "I'm very fond of children. Do you mind if I go and look at them?" He was on his feet, was crossing to the locked door beside the stove...

"Stop!" the woman snapped. "Leave that door alone!" Her ham-like hands were pressing down on the table, as if to lift her, but somehow she did not move. A look of surprise crossed her face. "My legs! I can't—They won't work."

"No, Mrs. Tintel," Doc smiled, humorlessly, from the door he was unlocking. "I'm afraid they won't. You see, I stopped at the store and gave Ted some extract of sativa, which he dropped into the essence in your mug, just now. He'd told me about your always drinking tea, and I figured that he might get a chance to do that when I got you interested in my proposition. That drug in small doses paralyzes the loco-motor muscles and that's exactly what's happened to you. I'm going in here, and you can't stop me." He turned the key, flung open the door.

There was another big room beyond it, another long table. This table was piled high with bits of colored tissue, with loops of green wire. Around it nine tiny tots, starved looking and unsmiling, were standing on boxes of various sizes to bring them high enough so that their flying little fingers could work with the tissue and the wire to fashion from them artificial flowers. Already big pasteboard cartons ranged behind them were half full of the paper blossoms.

"Asleep!" Doc said bitterly. "Working hours already to make these flowers so that they can go out by eight to start selling them over on Garden Avenue. Ted told me about that, about how if they bring any home unsold you beat them…"

"Look out!" Ted screamed, but the flashing, snake-like black coil that had wrapped itself around Doc's waist, that twisted him out of the doorway and slammed him against the wall between it and the stove, beat the shrilled warning. Breath driven out of him, Doc saw that the thong was the long lash of a whip whose stubbed handle was in Eva Tintel's powerful paw. It spun him, as it pulled away. It lashed at him again, cut his cheek open.

"Close that door, Ted," the woman shrilled, "and lock it." The hissing lash sliced at the boy to enforce the command, swept back to seethe about the old pharmacist before he could take advantage of the respite.

"Maybe I can't move my legs," the woman cackled, triumphantly, "but my arms is good as ever, and that's all I need to take care of you. Ted forgot to tell you I keep this whip under the table near my chair here, so as to make the brats behave while they're eating."

"Get out, Ted!" Doc exclaimed. "Get out of the house and call the cops." The boy darted for the entrance door, but the blacksnake whip was there before him. It wealed his bare chest and floored him.

Turner snatched at the big kettle, half-lifted it. The whip struck his hand with numbing force. The pot dropped, spilled its steaming contents. The vapors seethed around the stout fiend at the head of the table, but the black reptilian ribbon flashed out of the fog, crashed the old man at the wall, pinned him there.

"My grandfather was a mule-team wrangler on the old Santa Fe trail," Eva Tintel laughed. "This whip wuz his an' he taught me how to use it. I can pick a fly off your nose with it, and never break the skin. I can cut your ears off with it, blind you. That's what I'm going to do, too, unless you tell me what your game is."

Doc Turner had faced guns in the hands of desperate men, had plunged into red flames to save a life, had faced death in many forms and never blinked. But there was something different about this horror of a whip that circled and darted and flew through the air like a thing alive, something weirdly menacing. He cringed against the wall, hands to his bleeding face.

"Don't," he moaned, "don't cut me to pieces with it. I'll tell you what I'm after." He stared between his fingers at the monstrous woman, a she-devil surrounded by the cloud of steam from the boiling water he had spilled, and watched her livid lips, her eyes, piggish no longer, but bulging, their pupils dilated till the whites were mere bloodshot rims. "I'll tell you."

THE lash thudded to the table, writhed along it, ready to lift

and slash at the old man if he dared attempt escape.

Eva Tintel licked her lips. "Go ahead then. And no tricks."

"I'll tell you," Andrew Turner husked. "I came here because Ted made me. He made me come with him, so you would let him in."

"Let him in! Hell, if I'd known he wuz alive I'd of dragged him in. Runnin' away like that, pertendin' to be drowned."

"He didn't pretend. He is drowned. He is dead and she sent him back here to prepare the way for her. Mary Hoskins, the mother of little Ruthie whom you beat so terribly every night because she still prays that her mother will come back. Mary has been dead too long to be able to come all alone, but she could if the beginning of the chain was in the same room with you."

Terror crawled in the woman's face. "You lie," she husked.

"The beginning of the chain. Me, living on borrowed time. Ted, just dead, whom I could bring here. And—Mary Hoskins!" Doc's hands came away from his face. It was a scarlet mask, only the staring, appalled eyes anything but crimson. "Behind you! Ruthie's mother!" His voice was a high, piercing scream. "Behind you! Reaching her skeleton fingers for your throat. Your sins have found you out, Eva Tintel! She's got you!"

The woman half-lifted out of her chair. A shriek ripped from her throat, a shriek of incredible terror. She twisted...

Doc darted forward, snatched at the whip-lash, tore its handle from her hand.

The lax hand thumped down on the table-top, just before the obscene torso of the woman thumped down on top of it. Eva Tintel lay, a mountain of gray flesh, across the table, and did not move.

"Dead," Doc said aloud, letting the pulse-less wrist fall. "She's dead, Ted. You needn't be afraid of her any more."

"Dead?" The urchin was scrambling to his feet. "But—but you didn't touch her. How did you kill her?"

"Her heart was weak, as most fat people's are. I scared her to death."

"Scared her. Naw." The urchin shook his head. "She wasn't scared of anything."

"Probably not, when she was normal," the old man replied, something of horror still upon his face. "But she wasn't normal. You see, Ted, I had an ampoule of concentrated adrenaline in my fingers when I picked up the kettle. I broke it into the boiling water as it spilled, and she breathed it in with the steam. Adrenaline, inhaled that way, goes right into the blood stream and to the fear centers in the brain, and for a few minutes the person who has inhaled it is terror-stricken without reason, without knowing why. I added to that terror by the wild yarn I spun, by showing her my bloody face and screaming at her. I expected it only to make her faint, but it killed her."

"It killed her." There was wisdom beyond his years in the pinched little face Ted turned up to Andrew Turner. "Gee, Doc. Maybe it wasn't the fear-medicine, or your story, that killed her. Maybe you were more right than you meant to be when you said that her sins had found her out."

"What makes you say that, Ted?"

"That window, there behind her. It's open now. It wasn't open when we came in here. I saw it going up, little by little, while I was lying on the floor and she was whipping you. It was the cold breeze coming in from it that made her sure what you said was true."

Doc turned. The window was open, and he was quite sure it had been closed. He went slowly over to it, pulled it down, thumped on the sill.

The framed glass slid up again, slowly.

"Look, Ted. There's a piece broken out of the frame here. That made it lighter than the counterweight by just a little, and the concussion of that whip jarred it enough to make it open."

"Sure," the boy replied. "That's what I meant. She threw a flatiron at Ruthie day before I ran away. It missed Ruthie—and broke that piece out of the window frame."