RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

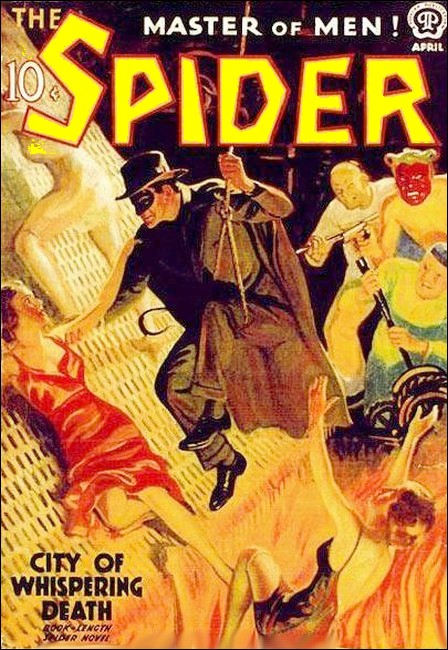

The Spider, April 1938, with "The Circle of Fear"

Into Doc Turner's little drugstore was carried the woman whose face had been terribly seared by acid. But Doc knew that an even greater menace threatened her—death dealt out slowly by fiends who killed their victims with fear!

HER shawl, which was black and knit in an intricate pattern, lay tightly over her head, hiding her hair. It was pinned close up under her chin, so that all one could see was her pale face—the red splash of her mouth, the pink lining of flared nostrils and the deep, lustrous brown of her eyes reflecting the grimy light spilling down from a fly-speckled ceiling fixture. It was enough.

The woman's skin, molded over wide cheekbones and a square, strong chin, had an odd suggestion of transparency. It was curious, Andrew Turner thought, that her face should be so placid, so devoid of emotion, when at the side of her jaw a bruise lay blue and angry, its hue deepening with the clotting of blood along the bone.

"He's struck you again," the old druggist said, his gnarled fingers tightening on the counter edge. "Why do you not at least let me speak to him, Marya Feodorov, and tell him how wrong it is to strike you—even if you will not go to court to have him bound over to keep the peace?"

"Sasha's blows do not really hurt me." The voice, deep-toned, warm and infinitely patient, was like an organ note pulsing against the shrill tumult which came into the dimly illuminated pharmacy from amidst the high-pitched, polyglot noises of Morris Street's pushcart market. "You see, it is not really he who strikes me, but his fear—the fear that is breaking him into little bits." There was no trace of accent in her speech, yet her enunciation was too precise to be that of one to whom English was a native tongue.

"Fear!" the pharmacist exclaimed. "You have said nothing about fear before. Tell me what he is afraid of, and I will—"

"No!" A tiny muscle twitched in the woman's cheek. "Thank you. You are kind and wise, but you cannot help us."

"Surely, I can." Doc Turner was small-bodied, seemingly frail. The years had whitened his silky mane, silvered his bushy, drooping mustache, lined his thin countenance with wrinkles. "I have helped so many others in my time." Weariness cloaked him like a grey shroud, yet there was an aura about him of some strange strength that transcended his years. "Many others, Marya, who thought they could not be helped."

An elusive smile touched her lips with bitterness, then was gone. "I know of your exploits," she murmured. "Who in this slum does not? But it is against the wolves who pray on the helpless poor that you have fought so well. Against those who circle my Sasha, with a slowly in-drawing doom, even your shrewdness and courage are futile."

Turner's eyes, a faded blue beneath shaggy white brows, lifted to hers. He shrugged, at last. "If that's the way you want it..." His tone changed to impersonal brusqueness. "It was a sedative you asked for, I believe?"

"Yes. Something that will give him some hours of dreamless sleep, so that he may have rest from his fear."

"I'm sorry," Doc said, "I cannot sell you a sedative except on a doctor's prescription. It is against the law."

Breath caught in the woman's throat, the sound not quite a sob. "The law!" There was hardness now in her voice. "I have heard that for you the law is not always sacred."

"Not always," the pharmacist assented, "when it has denied protection to my people." His look went past Marya to the shambling, alien throng on the sidewalk where brilliant electric lights abolished the night. "I have gone beyond the law for their sake. But in the conduct of my business I obey it. If your husband requires a sleeping potion, call in a physician to prescribe it."

"Physicians treat ills of the body, not of the soul," she argued.

"And a drug-induced sleep will not cure Sasha's soul. I am afraid, Marya Feodorov, that he will have to face..."

"The night lying against the window-panes," she cut in, "black with memories of what they did to our friends, who did not flee in time. He will have to face the whispers of crumbling mortar in the walls, the creak of old wood in the stairs outside the door and the slither of the wind on its panels, appalled lest this time they be the sounds not of crumbling mortar and old wood and wind, but their sounds, coming for him at last. I shall have to face the sight of the man I love crouched for hours against the wall, his palms outspread against it, eyes wide with terror."

That which she said was dreadful enough, but what made it almost unendurable was that it was said in that low voice, that her face was utterly still, expressionless, the cruel bruise darkening upon it.

"At last I will be able to endure it no longer," she went on, slim, white hands crossed on her black-shawled breast. "I will speak to him. He will snarl and lash out at me, beating me to the floor. At once he will kneel beside me, shaken with remorse, kissing the mark of his fist, begging my forgiveness. I will gather his great yellow head to my bosom and, exhausted, his lids will droop, and he will sleep for a little while. But he will whimper in his sleep till the fear in his dreams grows too great—then he will waken again to terror. That, Mr. Turner, is what Sasha and I will endure tonight because of your cruel law."

Grey, grim bleakness spread over the old druggist's face. "You will not tell me whom he is afraid of? You will not let me help you?"

"There is only one way you can help. Sell me the sedative."

Doc sighed. "No—" he said it gently, but there was an absolute finality in the monosyllable—"I cannot."

Again there was the half-sob in the woman's throat, the only hint of emotion that she had betrayed. She turned and went toward the door. Her small feet made scarcely any sound on the bare floor of the ancient pharmacy, and there was something proud, almost regal in the way she moved between the white-painted old showcases, out into the brawling tumult of Morris Street.

Andrew Turner was very still, looking after her. Like that, he was thinking, Marie Antoinette must have looked, walking out to the tumbril that would take her to the guillotine.

IN the archway cut through the partition behind him a frayed

and faded curtain pulled aside. A barrel-chested, carrot-topped

young man came through it, out of the prescription room at the

rear of the store, and turned to the druggist.

"Gosh," Jack Ransom said, "you're getting tough, Doc. Why didn't you let her have the stuff?"

Turner looked somberly at the burly youth. "I've got to break her, Jack."

"Break her!" Ransom's freckled visage gaped with astonishment. "What do you mean?"

"If she can bring relief, even only temporary, to her husband, she will cling to her hope that somehow, by some miracle, they will be able to work out their salvation alone," Doc explained. "If she can't, she will come to me for the only kind of help that will do them any real good. She'll tell me what it's all about and let me go to work. She has been trying to get a sedative for a week now. Tonight, for the first time, I saw signs of her breaking. Before this, she would only tell me that her husband was ill and that they were too poor to pay a doctor and too proud to go to a clinic. This time, she was really on the verge of telling me the truth."

"Cripes, Doc, it sounds screwy to me!" Jack admitted. "If there really was anyone after them, they'd go to the police for protection. It looks to me like this Sasha guy's nuts, and his wife's simply trying to cover him up. Best thing for them both would be to have him put away. I don't see what call you have to get mixed up with them."

The older man shook his head. "No, Jack. Feodorov is not mad— nor is Marya. That impassive look of hers is a mask, worn so long to hearten him that it has become second nature to her. Beneath it there is the same heart-stopping, icy fear that she describes as afflicting her man."

Jack grinned. "Well, I've got to be shown. I need some proof. I'm from Missouri and—"

A scream, thin, shrill with terror, knifed into the store's hush from outside. The usual clamor of the slum changed into the pound of rushing feet, raucous shouts, yells—all loosed by that woman's keen cry of anguish.

"That's Marya!" Doc exclaimed, and was around the edge of the counter in a flash, darting through the shop and out into the street. Ransom pounded close behind. A jostling crowd was everywhere, streaming toward the corner, carrying them with it.

The scream was coming from the very center of the shoving, pushing mob. "Let me through!" Doc ejaculated, thrusting at shoulders clothed by thread-bare fabric, wriggling into the close-packed mass of humanity whose body-sweat was rancid in his nostrils. "Let me through to her."

They made way, so powerful was the love and respect in which these children of poverty held the little old pharmacist.

In that congested vortex, Marya Feodorov was crumpled on her knees, hands clamped to her face, moaning. Wetness dripped from beneath those hands, down across her black shawl, turning it to a poisonous orange.

Doc sniffed an acrid tang in the air. "Acid!" he exclaimed. "It's in her face!" His gnarled fingers snatched at Marya's wrists, tugging. "Your eyes, Marya? Did they...?"

The hands came away and, stark with anguish, Marya's great brown eyes stared at him. "Thank God," the old man gasped, seeing that they were unharmed. But across the woman's left cheek, down over her chin, the white skin was seared scarlet.

"Holy smoke, Doc!" Jack Ransom's voice hammered in his ears. "They threw—"

"Get her to the store," Turner snapped. "Quickly!"

THE youth bent, his shoes crouching on splinters of glass. He

scooped Marya's quivering form up in his great-thewed arms and

almost without perceptible effort, lifted it. The crowd was

already parting for Doc, when Jack turned. He went through the

passage that was lined with wide-eyed alien faces, and around the

corner into the pharmacy.

By the time he got to the rear of the store, through the curtained doorway into the back-room, there was a large basin on the white-scrubbed top of the prescription counter. Turner was pouring into it the contents of a bottle labeled, Solution Sodium Bicarbonate, 10%. The pharmacist jerked his head to the battered swivel-chair set before a cluttered, roll-top desk. As Jack deposited his now softly moaning burden in this, Doc doused a great wad of absorbent cotton into the basin.

The druggist at once lifted the soaked cotton out of the liquid and, almost before Jack could step out of his way, had it covering Marya's face. There was a violent sizzling underneath the wet mass. The woman's moaning stopped.

"Get me more," Doc commanded.

It took three changes of the neutralizing solution before Marya gasped weakly, "It pains but the burning has stopped."

Turner lifted the last wad and signed to Jack to look at the splotch of red, raw flesh that disfigured the beauty that had been there.

Tiny muscles knotted along the youth's blunt jaw and his eyes were deep-sunk balls of grey agate. "You win," he muttered "It's something damned real she's afraid of." His great hands knotted, slowly, to sledge-hammer fists.

"How did it happen, Marya?" Doc asked gently. "Who did it?"

"I—I did not see. A glass ball came out of the darkness of a tenement vestibule and struck my face. Only by a miracle did the acid not splash into my eyes." The woman thrust feebly at the arms of the swivel-chair, trying to rise. "I must go to him—to my Sasha."

"Wait." Doc held her down with tender but firm pressure. "I still must apply this healing ointment and bandage your face." He strapped a salve-spread gauze pad to her face, as he went on, "If Sasha sees what it looks like now, he will go mad, as your enemies intend."

"Mad?" gusted from the woman's charred lips. "That is what..." She stopped.

"That is what they want," agreed Doc. "That is why they have not killed him, as it would be so easy to do in that rabbit-warren of a tenement where you live. Why do they want your Sasha alive and mad? Tell me, Marya Feodorov, before it is too late."

She stared at the old man, and it was terrible to see the way her indomitable courage was shattering, there in the depths of her eyes.

"Mad—and alive," she whispered. "I had not realized. They want to take him back..." The creak of the front door's hinges interrupted her, heavy soles thudding toward the partition.

"It's the police, Doc," Jack said from the curtain. "A cop."

"The police!" Marya's fingers snatched at Doc's sleeve. Her voice was taut, abruptly, with apprehension. "They must not know. They must not..."

TURNER jerked away from her, was through the curtained doorway

and out in front as the policeman reached the sales counter.

"Hello," Doc said quietly. "What are you after?"

"There was a woman hurt outside and brung in here. I want to ask her about it." The other stared angrily.

"That Polak?" Doc smiled. "She just got splashed with some water out of a window and thought she was burnt. There wasn't anything wrong with her."

"No? She made a hell of a fuss about it from what I heard," was the retort. "Maybe I better talk with her. Where is she—in back?"

"No." Very casually, Doc stood in the space at the end of the counter, blocking off the patrolman who had started to move through it. "No, she's not there. I let her out through the side door because she was ashamed of the way she had squalled about nothing and didn't want to face the crowd out in front. She's home by this time."

"Yeah?" The policeman's eyes narrowed suspiciously. "And where's that? What's her name and where does she live?"

Doc shrugged. "I didn't ask her. I was so annoyed with her for making a pest of herself I didn't talk to her any more than I had to."

"You wouldn't be kidding me, would you?" the cop inquired. "You wouldn't be stalling me? I was told you took one look at her face and said something about it being acid that wet it. Maybe I better take a look inside, just in case. Got any objection?"

"Yes." Andrew Turner's lips were tight under his mustache. "I have a very definite objection to anyone's entering my prescription department unless I invite him. That portion of this store is just as private as if it were my home. You'll have to have a search warrant to go into it."

"Says you," the policeman grunted, and his hand lashed out. His fingers seized Doc's shoulder, dug to the bone. "We're going back there, you and me—and you'll like it." Fiercely, he forced the old man through the curtain, into the back-room.

No one was there!

"Skipped!" the cop exclaimed, shoving Turner's back against the edge of the prescription counter. "You tipped her off to skip out that side door, when you was talking about it to me."

Doc's hands went behind him as if to ease the pressure against his spine.

"It means that she's been gabbing plenty, and that you know too damn much for your own good." The policeman's free hand went to his holster. "But you ain't going to know that a hell of a lot longer." The hand came away from the holster with, not a revolver, but a slim, triangular stiletto, clutched in its fingers. "And yelling ain't gonna do you no good, because I locked that front door as I come in, and I see this one has a spring lock on it."

"You're right—I sent her out." Doc said, very calmly. "I knew you were no policeman as soon as I saw that you had the wrong precinct numerals on your collar. The dividing line between the ninth and the eleventh goes through the center of Morris Street. When you got that uniform, you intended to use it on the other side of the street, where the Feodorovs live."

"A smartie, ain't you?" The impersonator scowled. "Let's see if you're smart enough to laugh off steel in your gullet." The stiletto lifted slowly. "I think I'll let you have it between the ribs. That way there won't be so much blood." It drifted toward the old man's breast, six inches of keen-pointed lethal steel. "I—ker-r-choo!" A sudden sneeze ripped from the killer's nose.

Doc jerked away, emptied the rest of the contents of the small bottle in his hand into the supposed cop's face. The dagger clattered to the floor, and the fellow began clawing at his eyes while his mouth gaped with rasping, choking screams, or snapped shut and open again on retching sneezes, tears streaming down his brutal jowls.

"Perhaps," the old druggist said, "you can laugh off powered capsicum—red pepper—in your eyes and your throat. You should have watched what I was reaching for behind me."

"A-hhchoo!" An unintelligible bellow came from the badgered assassin, and he leaped blindly toward the sound of the druggist's voice, hammer-like fists flailing wildly. Doc dodged to one side. The fellow charged past him in a blinded, berserk rush. Then the old man suddenly stuck a foot between the frantically scissoring legs—tripping them. He went down, heavily. It happened that quick.

His head struck a corner of the drawer, still open, from which had come the cotton to wash Marya's wounds. He sprawled, abruptly, was very still—an inert, crumpled heap.

"The devil," Doc exclaimed, kneeling to feel the thick skull. His hand came away red, but he was relieved to feel the killer's pulse.

"Not dead," he muttered. "However, very thoroughly knocked out. The Lord alone knows how long it will take him to come to." He rose wearily. "I had hoped to extract so much information from him. Well, I shall have to wait till he recovers consciousness. Meantime—" he drew a roll of adhesive tape from another drawer— "I'll make sure I have no trouble with him when he does come around."

HE taped the unconscious man's ankles and wrists, fashioned a

gag out of absorbent cotton, and stripped the adhesive securely

across the fellow's mouth. Then he straightened, sighing.

"He was sent to find out how much Marya had told me," he mused, half aloud. "Knifing me was his own idea, when he found me alone. But it means that their plans are coming to a head. They're determined that nothing must interfere with them. As soon as Jack comes back... Good Lord" he muttered "I wonder if that red-headed young rascal..."

He looked inquiringly around him. A bottle carton faded blue in color, lay among the papers on the roll-top desk. The name printed on it was Nastin's Coughex, and it was years since that particular preparation had been taken off the market. The carton was used as a signal between Doc and Ransom. Placed in the display window, it would call the garage mechanic to the drugstore without betraying the fact that such a call had gone out. Its usual place was on a shelf at the rear end of the prescription room. Jack must have removed it from there during Doc's interview with the masquerading cop.

Doc stepped over the recumbent body of his prisoner, reached the desk. He lifted the carton. Scrawled on the back was a penciled message. "Got you," it read. "Taking her home. Going to have a talk with Sasha."

What little color there was in Doc Turner's wrinkled cheeks now seeped away. His eyes slid across the floor to the vicious shaft of blued steel that lay glittering against the base of the prescription counter.

THREE-QUARTERS of a block from the lights and clamor of Morris

Street, Hogbund Lane was a darkness-infested, malodorous gut

lined with sleazy tenements. Marya Feodorov stopped at a high,

broken-stepped stoop and turned to Jack Ransom.

"This is where we live," her low voice throbbed. "I will be all right now. Thank you for your kindness, and good-by."

Jack shook his head. "No, lady—not good-by. I'm going up with you. I'm going to talk things over with that husband of yours."

"That," came the deep-throated response, "is impossible. He will see no one, speak with no one. He trusts no one but me."

The carrot-topped youth shrugged. "All right," he murmured. "But that means I'll have to go to the cops and send them around. You've got to have some kind of protection. This is America, you know, and we don't allow..."

"You will not go to the police. If you do, we..." she checked herself.

"Yes?" Ransom asked softly. "What will happen if the police come in on this?"

"They will find out that we are not in this country by right. We are—illegally entered aliens and—"

"You'll be deported?" he finished for her. That's what she was trying to hide.

"We will be sent back to—to the land from which we fled by night. Sent back to a living hell of unimaginable tortures. You will not—you cannot—do that to us."

"Guess again." Jack was tight-faced, grim. "I'll do exactly that—unless you take me upstairs with you to see your Sasha. I'm in this business now, and staying in!"

A long moment of silence was broken at last by Marya's quivering sigh. "Very well," she said. "If it must be, it must be. Come."

She turned again, and, without a further word, went up that stoop. Jack followed through a dark vestibule, up steps again— up many creaking wooden steps along which ran an unpainted, splintered railing. Those stairs were dimly lit by pinpoint gas-jets, bracketed to the broken-plastered walls only at alternate landings. The air in that stairwell was thick with the smell of poverty—the stale odors of foods heavily seasoned to make them in some degree palatable, the rancid stench of unwashed, sweaty humans. But through the dimness and smells Marya Feodorov climbed with her inimitable, proud grace.

At the third landing, she went back toward a dirt-streaked door barely visible in the wavering shadows. Jack heard the scrape of fabric against the panel, as she neared it—and a hiss of breath that was actually a gasp of terror.

A loose board creaked under Ransom's feet, as he kept close behind her.

"Who is there?" was whispered sharply from behind the door. Again, louder, but in a voice choked out of a tightening throat, "Who is it?"

"It is I, Sasha," Marya said to the door. "Be not fearful. It is Marya."

"Marya! But why then do you not give our signal knock on the door?" The voice was stronger, but still edged with hysteric fear.

"Because I have something to tell you, before you open," replied the woman. "I—I have a bandage on my face, Sasha. I have been hurt, but not badly."

"Hurt, Marya, my beloved!" The doorknob rattled.

"Wait!" his wife said sharply. "Wait, Sasha, before you open. I have something else to tell you. I have one with me—a friend."

"You lie!" the man inside snarled, and Jack could almost see the lips lifting from his teeth, eyes bestial with rage. "We have no friends. You have turned against me. You have brought one of them with you. I knew that in the end you would turn against me."

Even in the half-light, Ransom could see that the woman's eyes were stricken. "But, Sasha," she said, and none of the agony with which her man's accusation tortured her, was in her voice, "by the ikon upon my mother's grave, I swear that it is a friend I bring to you. An American, Sasha, and a friend. He has helped me and comes to help you."

"By the ikon on your mother's..." There was a pause. "You would not dare to swear falsely by that. But how can I be sure? They have slain the old faith, and you..."

"We prayed together, this evening before I left. Was not the old faith alive in me then, Sasha?" she asked. "The old faith, and my love for you? Could I have forgotten that in two short hours?"

Again there came a long moment of throbbing silence, and then, "No," the man behind the door sighed, "not in two centuries." The doorknob rattled again, a key clicked in the lock, and the door opened.

"Come," Marya Feodorov said to Jack, "he permits us to enter."

THE door, opening inward to let them through, hid the man,

slammed shut and its lock clicked. Jack found himself in a room,

bare to starkness, its only furnishings a coal range, wooden

kitchen table and two chairs. The provisions on a wall shelf over

the galvanized iron sink were pitifully scarce. A black shade was

pulled tightly down over the single wide window. Another door,

tight shut, must lead to a bedroom. Everything in sight was

almost painfully clean.

"Marya," Ransom heard the shocked exclamation behind him. "Your face!"

"It is nothing, Sasha—a scratch," she explained. "The druggist on the corner bound it for me. It is nothing at all."

The husband was gigantic, yet also thin to gauntness. The blouse of maroon silk had a high collar that folded about his neck. His countenance was molded in broad strokes, cheeks hollow, eyes burning from the depths of blue-lined sockets. His hair was honey-colored, silken in texture. His long, carefully tended fingers weaved, one over the other, continually, never a moment at rest.

"She isn't telling you the truth," the redheaded youth said, the words thudding against his palate. "That's not a scratch on her face. It's an acid burn. The acid was thrown at her by the people you're hiding from. It missed her eyes only by a miracle."

"Marya!" tore from Sasha Feodorov's pallid lips. "Your eyes! You might have been blinded!"

"Yeah. She might be in the dark now, forever," growled Jack. "And you would have blinded her, sending her out to get a sleeping powder for you while you skulk here, hiding behind a locked door. You call yourself a man, I suppose. Maybe that's the way a man acts where you come from. In this country, we call anyone that acts like that a skunk."

The woman whirled on him, her countenance livid. "You dare to speak thus to Sasha Feodorov!" she exclaimed. "You dare..."

"Quiet, Marya." Two grey spots had appeared on either side of Feodorov's finely chiseled nose. "The American is right. Too long have I shielded myself behind your skirts. I will handle this!"

"Damned right, you've hidden behind her skirts," Ransom snapped.

"Who are you?" Sasha whispered.

"That doesn't matter much, except that I hate a coward," said Jack. "She told you that I'm a friend. I'm her friend—here to try and help her. If you were alone in this, I wouldn't move my little finger for you. But she's in danger because of you."

"In danger because of me!" The blond giant whispered it. "Yes... you are right." He started moving toward Jack, slowly. "They threatened Marya now to torture me." He went past the youth, walking like a sleepwalker.

He reached the table. His hand pulled at a drawer handle. "But you cannot help her. No one can, but I—like this!" His hand darted into the table drawer, flashed out with a long carving knife. The knife arced toward his throat.

Jack hurled himself across the narrow space. His left hand slashed the knife from Feodorov's fist.

"You fool!" Ransom grunted, watching Sasha stagger back against the wall.

"I would have followed you, my Sasha," the woman moaned, "to the hell where you would have sent yourself by that act."

"Yeah," Jack snorted. "She'd go to hell for you—to shield you from Satan's fires with her own body—but you haven't the guts to fight for her!"

"Fight for her?" Feodorov was flattened against the wall, eyes wide, little lights crawling in their blue depths.

"How the deuce do you expect me to tell you unless I know what it's all about?" Jack said. "Come on, mister, spill it. Who's after you, and why?"

"Tell him, Sasha." Something about that chunky, big-fisted, red-head—something in his frank clean-cut Americanism—had gotten through to the woman at last, inspiring confidence. "Tell him, my beloved."

Muscles rippled under her husband's pallid skin.

"Spill your story," Ransom urged, "and I'll go the limit fighting for you."

"MY story?" Sudden decision was mirrored in Feodorov's

countenance. "It is far more than my story. It is the story of a

dream become a nightmare—the violation of an ideal that

might have remade the world."

"Yes?" Jack prompted.

"It smoldered in the Old World, among the downtrodden, that ideal," began the man. "It flared up in a great flame, consuming the ruins of a derelict empire, lighting up the earth with its flame. The brotherhood of man—a commonwealth of all, for all, by all! No reward was to come to its leaders save the satisfaction of having served their brothers. That was the dream, and I was a part of the dream." He paused.

"We thought that by abolishing money, by setting before men the goal, 'From each as much as he is able, to each as much as he needs,' we should abolish the greed-motive upon which older political systems have been wrecked. But we could not abolish the lust for power—and it was the greed for sheer, absolute power that made a dictatorship out of a brotherhood." He frowned.

"One man's lust for power developed slowly, glossed over by the words of the ideal. The 'dictatorship of the proletariat' was a beautiful phrase. I served it, as ambassador to a foreign power, served it till trials that were a mockery of justice, purges that were massacres, woke me to the realization that the dictatorship of the proletariat had become the dictatorship of one man!"

Jack stared, as the speaker went on.

"My friends, waking as I did to the death of our dream, protested in the privacy of their own homes. They were summoned back to our native land—and, with inconceivable cruelty, made terrible examples, to terrorize a nation into subservience to that one power-maddened man." There was a pause.

"Because I held certain secrets that even the man feared, if revealed, I was immune for a time. And then the summons came for me," said Marya's husband. "I did not obey it. I fled to Paris, at first. His myrmidons found me there. By a lucky accident, the gendarmes rescued me, but I was warned to leave France. She would not chance affronting a possible ally in the great marshaling of forces that prepares for a war not too remote." Again, he hesitated.

"I went to London, secretly, and this dictator's cohorts found me. Once more, I escaped, once more was warned. I came to this land, sought to hide myself here, among the unregarded poor, the downtrodden. And now, again, they have found me." His hands spread wide. "There is no longer anywhere I can flee."

"I get it," Jack remarked. "But look—why don't they kill you? They've had plenty of chances."

Feodorov's nostrils pinched together. "I have defied an order. Death is not to be sufficient punishment for me. I must be brought back to the dictator. I must grovel in the dirt before him. I must be made a public spectacle, so that none again will dare defy his order, even if to obey it means death."

"That's a hell of a note," growled Jack. "But maybe we can figure out..."

"There is no need to trouble yourself!" It was a new voice, guttural, icy.

MARYA vented a little scream as Ransom whipped around to

locate that new voice. It came from the bedroom door, open now,

framing a short, satyr-countenanced man from whose black-gloved

hand a blued automatic snouted.

"Gregor," Sasha named the man in a flat, dead voice. "Gregor Rastunin."

"Exactly, Tovarishch Feodorov," said the other. "You have escaped me twice, but this time you shall not. The arm of the man of whom you spoke is long, and those who serve him are innumerable. Stay where you are, American. At your least move, I will fire—at the woman."

Jack's breath pulled in.

"Back against the wall there," Rastunin directed.

There was nothing to do but obey.

"You can't get away with this," he said tightly. "This is the United States."

The fellow ignored him. "Pavel," he said, "proceed."

Jack measured the distance. Would a sudden leap...? No. The table was between them, and that automatic was very steady, aimed pointblank at him. Another man came through the doorway—a hulking brute. His face was black with coal dust, a coil of wire was in his spatulate fingers and, over his big-thewed arm, were burlap bags also blackened.

"Bind and gag the American first," the dark man commanded. "He is the most dangerous. But he will not be dangerous when he lies many fathoms under the greasy surface of their river. They are used to seeing bags of coal carried up and down these stairs," he said to Ransom, "and it will be as a bag of coal that you will be carried out of here."

Jack's biceps knotted.

"Remember," Rastunin murmured, "it will be Marya Feodorov at whom I fire first if you try any tricks. If you give us no trouble, she will be set free when we arrive aboard the destroyer that lies in wait for us in the harbor. Tovarishch Sasha, of course, will go with us to meet his fate."

The one called Pavel stood before Jack. Dropping his bags on the floor, he grabbed Ransom's hands, brought the wrists together. His wire wound around...

THEN a sudden, surprised look filled Rastunin's face. Abruptly

he crumpled to the floor. The black shade over the kitchen window

now rattled noisily up on its roller and a small, white-haired

figure slid into the room. Pavel whirled, gurgling, and Doc

Turner's acid-stained fingers squeezed a white rubber bulb. A

fine stream of glinting liquid shot from it, sprayed into the

coal-grimed countenance of the brute who was leaping toward him.

Pavel clutched at his throat, banged blindly into the table, and

collapsed across it.

"That combination of ether and chloroform works fast," Andrew Turner remarked, smiling at Jack, "when it's sprayed from an atomizer like this. But I didn't think I'd get the window pane cut out in time, from the fire escape outside."

"Doc!" Ransom gulped. "How did you get here? How did you know to climb the fire-escape?"

"I knew something was going to happen very soon." The old druggist explained slowly. "I was sure that you'd be mixed up in it. If I called the police, I'd get you out of trouble, but the Feodorovs would be sure to be deported. I hurried over here, saw these two slinking down into the basement from the hallway downstairs, followed them. I saw them climb the fire-escape, then across to the bedroom windows—which Sasha here didn't think it necessary to lock—finally, climb in. I'm an old man and it took me quite a while to climb the ladder and cut out the glass."

A chorus of tearful thanks from the Feodorovs interrupted, but Doc fended them off. "You two are going to get out of here," he said, "right away. You're going to take a train to a small town in the Midwest, and, when you get there, you're going to change your names and act like normal human beings. This is a big country, and you'll never be discovered if you do that, instead of calling everyone's attention to you by hiding. Now, get busy and pack your stuff and get out."

"What are we going to do about these two, Doc?" Jack asked when the idea finally percolated into the Feodorov's heads, and they went off, like children to obey the pharmacist's instructions. "We can't just leave them here."

"No," Doc smiled, working at the wire that still bound Jack's wrists. "We're going to tie them up with these wires and stuff them into the coal bags—carry them over to my store. Then we're going to call the police and report an attempted hold-up. They know us well enough not to wonder how we could have overcome three mobsters."

"I'll say they do," Jack grinned. "It wouldn't be the first time we've done something like that."