RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

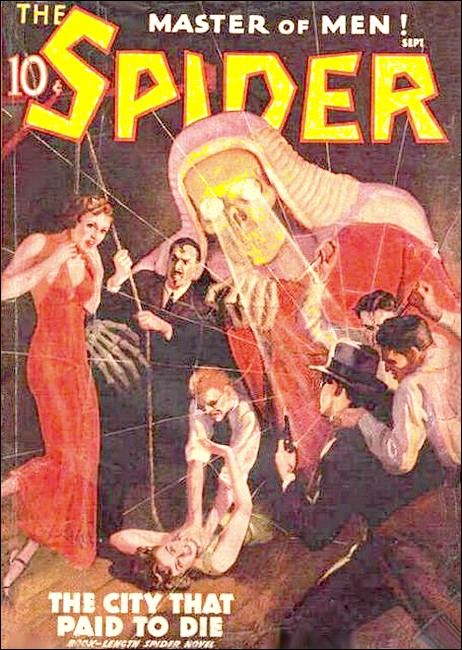

The Spider, September 1938, with "Torture on Morris Street"

Doc had fought many weird battles in defense of his crime-oppressed poor, but never before had he been called upon to battle a murderous spy clique—armed with no better weapon than a pinch of table salt!

THE pound of traffic on the cobbles under the shadow of the "El," the shouts of the pushcart hucksters and the shuffle of weary feet on the broken and debris-strewn sidewalks of the slum thoroughfare, came only dully into the drowsy drugstore on Morris Street. Here grimy light slid lazily along shelving once white, filtered slowly down over showcases ponderously framed in the fashion of the days before streamlining, lay in weary pools on a floor whose rutted boards were innocent of covering.

Doc Turner leaned on the scarred sales counter at the rear of his store, beetling, shaggy brows veiling his eyes. He was tired, as he always was these days. He was an old man. The years had frosted his silky crown of hair and grizzled his bushy, drooping mustache and etched deep into his hollow-cheeked countenance lines of age and weariness.

The years had faded the blue of his eyes, but had not dimmed their kindliness. They had stooped his shoulders and filled his old bones with aches, but had not dulled the acuteness of his brain. They had not lessened his leonine courage.

He looked up at the opening of the drugstore's door and the entrance of someone whose eyes were distressed, whose lips were grey and quivering with fear, and whose hands fluttered out to the old pharmacist in a gesture of wordless appeal.

It was a young woman, not much more than a girl. Her neat print frock clung caressingly to the lithe, slender curves of womanhood recently attained. Her tawny hair was cut in a "page- boy bob," but its curls turbulently refused the straight lines called for by that latest mode of coiffure. They framed a countenance narrow, pert-featured, blunt-chinned—gaunt now with dread but still winsome and characterful and endearing.

"Doc!" She was only half-way into the store when she spoke, her voice low and mellifluous but tight as the grip it was evident she had on herself to keep her from collapsing. "Oh, Doc—will you help me?"

"Of course, Joan Felton," the old man responded unhesitatingly. "Of course, I'll help you." He came around the end of the counter to meet her. "You don't doubt that, do you?" His hands, blue-veined and gnarled, their yellow skin transparent to show the bones within, took her soft, white ones into their heartening clasp. "Did I ever fail to help you, since the days you used to bring your wounded dolls in here for me to put iodine on?" His smile was warm and tender. "What doll's been hurt now, Joan?"

"It's Tom." The jitter under the grey surface of her eyes eased a little. "My Tom. He wasn't home when I came back from work. He wasn't there, waiting for me. And he hasn't come back yet."

"Is that all?" Doc chuckled, "Is that what's upset you so? Maybe he went out to get some chemicals for his experiments and has been delayed. Maybe he just got tired of the smells and decided to take a walk to blow them out of his lungs."

"He's never done anything like that before in the two years we've been married," she objected. "He's always had the table in the kitchen set and the gas on under the pots, warming the supper I've fixed in the morning. You know that."

"Yes," Andrew Turner responded. "I know that." He knew that the marriage of the Feltons was a partnership unique even in this neighborhood, where twisted lives were not unusual.

JOAN NOLAN and Tom Felton had grown up on Morris Street

and he had watched over them from the cradle. Tom had early

manifested an interest in, and a genius for, science—had

pursued its study, in night schools, in the libraries, terribly

handicapped by the necessity for earning a living that had been

fastened upon him at an early age. That necessity—the fact

that since the depression there was little place for younger

scientists in the industrial world—had thwarted his

ambitions.

Then had come marriage with Joan, and release. The girl had insisted that their only chance for escape from the morass of poverty into which they had been born was through Tom's pursuing the researches he had outlined for himself. She was employed, in a swank millinery shop on Garden Avenue. She was earning enough to support them both, meagerly to be sure, but sufficiently. Pooling their small savings, they had equipped a small laboratory for Tom in one room of the basement flat they rented. Joan continued to work and her young husband labored at his beloved science.

They were very much in love and very happy. They were the happier because they had hope—the commodity that was so scarce on Morris Street. But now...

"Something's happened to Tom," Joan quavered.

"Wait," the old man said quietly. "Wait. Let's be calm about this. You're a sensible girl. You wouldn't be so frightened at his absence if you didn't have a good reason. What is it?"

"It—it's his secret." A vein throbbed in her throat, and her pupils dilated.

"His secret?"

"He used to tell me, every evening, all about what he'd been doing all day, what he was trying to accomplish," she explained. "About—about six months ago, he started on something new. He put a lock on his laboratory door and didn't give me the key. He wouldn't tell me what he was working on. He begged me not to ask him. He said it was—too dangerous for me to know."

"Too dangerous?" Doc repeated.

"Yes."

The old druggist's face grew bleak. "And you think that the knowledge was dangerous to him, too? That the danger has become a reality?"

The girl nodded. Then, "There's something else. I—he left a note for me. On the kitchen table."

"A note. Doesn't it explain his being away?"

"It seems to." Joan was fumbling in her bosom. "But—but it's not right. It frightens me more than anything else." Her hand came out with a folded paper. It was ruled in tiny squares, the graph paper scientists use to chart their observations, and there was writing on it.

Doc took it. The meticulous, square-lettered writing was crammed at the top of the sheet.

Joan Dear,

I have to go away for awhile. Don't worry. I'll be quite all right. If you need any money, show this to Doc Turner, the druggist on the corner, and he will help you out.

Tom.

The old man looked up. "What's not right about this?"

"It tells me nothing at all that he'd know I'd want to know, and it tells me something he knows I don't have to be told," she said. "Don't you see? 'Doc Turner, the druggist on the corner.' Why does he put that in? Why does he say, 'if you need money,' when all our money is my pay and his being away wouldn't make any difference in that?"

Doc nodded.

"I see," the white-haired pharmacist said softly. "The phrase, 'the druggist on the corner' wasn't meant for you. It was meant for someone else. But since it was written in your flat, that someone else was there with Tom, was reading the note as Tom wrote it."

Joan's lips twitched and her fingers dug into Doc's arm. "We had no friends. No one ever came to see us. Who could it have been?"

"I don't know, yet." The old man seemed drawn into himself, his eyes burning, his tone far away, musing. "There's more to this—much more. Look. 'Show this to Doc Turner.' I wouldn't need a note from him to get me to do anything I could for you. He wanted you to bring this paper itself to me. He wants me to find something on it that isn't apparent—something hidden."

"That's it," the girl breathed. "It isn't money you're to help with. It's something else, and the paper's supposed to tell you what. But the message is invisible."

She waited.

"Invisible?" Doc spread the paper on the top of his sales counter, and his acid-stained fingers drummed an odd, rhythmic cadence on it. "Invisible? But with an enemy watching him, Tom couldn't have been able to prepare invisible ink, or to use it. Why did he cram his writing at the top of the sheet? ...I've got it!"

"What?" Joan cried.

"How his message was written, and how to read it." The old man's tones were excited now. "Come on." He plucked up the paper and darted around the end of the counter, through a curtained doorway in the partition behind it. The girl came after him, her breast heaving.

THE long, narrow room behind the partition was Doc

Turner's prescription-room. He went to the white-scrubbed,

immaculate counter where he had compounded medicines for longer

than he cared to think, slapped Tom Felton's mysterious missive

down on it. From a row of pegs he took a huge, glass beaker, from

a shelf over this a glass rod. He folded the paper over the rod,

written-on side down, laid this across the top of the beaker so

that the note hung within it.

His fingers were trembling a little, as he lifted down a small, glass-stoppered bottle filled with glinting, dark purple crystals. "When you were a pig-tailed child, Joan, I used iodine on your dolls. I'm going to use it for you now in a very different manner." He spilled some of the crystals into the bottom of the beaker, deftly. "Watch."

Another swift motion of those efficient old hands of his and a little alcohol lamp was lit. Turner picked up the beaker, with the paper hanging like a small tent, white and floorless, within it, and held it over the almost colorless flame, moving it gently to and fro.

She watched.

"Iodine doesn't burn or melt," he explained. "It sublimes—that is, passes directly from the solid state to a vapor... Ah, there it goes!"

The dark needles in the beaker crinkled at the edge, became perceptibly smaller. Purplish red fumes boiled up, filled the little tent, curled around its edges. Doc set the beaker down, lifted Tom's note from the rod and spread it out on the counter.

"There are marks on it!" Joan exclaimed. "Look." She jabbed a shaking forefinger at the space under the ink-written lines.

"Yes," the old man sighed. "I thought there might be." The space that had hitherto been blank was scrawled over now with thick, fuzzy-edged black lines that ran together and made crudely formed letters. "While Tom was writing the note at the top with his right hand, one of the forefingers of his left, wet with saliva, was making these marks, probably concealed by the way he bent over the table. When he blotted the ink writing, he also dried the saliva, so it left no visible trace—but the fibers of the paper had been disturbed. The iodine has settled in the microscopic roughness."

"What does it say?" Joan's voice was thin, knife-edged with hysteria. "I can't make it out."

The old man's faded eyes peered at the message. The clumsy letters were disjointed. The first was an R with a sort of line across its lower right corner. Then came an I, and an N. Following these were P, T, R, S, and T. Beneath this were other letters. Doc finally made out at T, K, 2, U, S, A, R, M. The M was half off the paper.

"What does it mean?" the girl wailed. "What is he saying?"

"Did you ever write to each other in code?" Doc asked. "In any kind of secret writing?"

Joan stared at him. "No." Her fingers were twisting within one another. "No, we never did."

"Then this hodge-podge must be simply abbreviations, because of lack of time and space," Doc said. "Of course—that first letter is Rx, our sign for prescription, for formula. He's writing about some formula—that's I-N, in, something. He hid a formula in P—P—"

"It's PT, Doc," Joan ventured. "Couldn't that be pot?"

"Of course. In a pot. But what pot?"

"Not a pot. In the P-T-R-S-T—the pot roast," she cried. "I left a pot roast for tonight's supper, half done. It's on the stove now."

"'Formula in pot roast.' That's it!" Doc was excited now. "Whoever was with Tom—whoever took him away—was after some formula. But the boy managed to hide it in the pot roast. Now, we're getting somewhere. Look! These last few letters are plainly intended for U. S. Army—to United States Army. The TK is take. There's your message! Left formula in pot roast. Take to United States Army. And that makes it all very plain."

Too plain, the old man thought. Tom Felton's secret research had been on something of military value. He had completed it—and before he could do anything with it, had been abducted. That could mean only that some emissary of a foreign power was involved in the young chemist's vanishing.

A spy!

The spy would be after the formula. But Tom had managed somehow to conceal it. His concern had been to get the recipe to the authorities, not for his own rescue. His secret existed in one other place than the pot roast on his wife's stove. It was in his brain, also! There was a sudden chill in the old druggist's blood, and the look in his eyes was one from which more than one of the coyotes who prey on the very poor had quailed.

He turned, plucked a faded blue, bottle carton from the shelf behind him, snatched up a pencil and scribbled something on this.

So swiftly was this done that Joan had no time to say anything, and then Doc grabbed her elbow.

"Come on," he grunted. "Back to your flat. Hurry!"

HE didn't stop to turn out the lights in the store,

scarcely took time to lock its door. The swarthy-faced aliens of

Morris Street turned to look at the couple, the white-faced girl,

the hatless old man with burning eyes, who ran around the corner

into Hogbund Lane. A carrot-headed young mechanic, lounging in

front of a garage, straightened, but the couple went by him so

fast that he had only blinked his startled eyes before the

tenement-lined gut had veiled them with an odorous dimness.

The two passed flocks of yelping children, broken-stepped stoops crowded with chattering housewives, with unshaven men under-shirted and sodden with the weariness of a long day's labors. They veered to the left, abruptly, went down creaking wooden steps into the darkness of a cellar musty with the stench of sewage.

Joan took the lead here, sure-footed in the familiar precincts. "I left the light on," she gasped, "but the door must have swung shut." Her slender form blotted a thin vertical line of yellow, and then this was widening to become a doorway through which she and the old man went into a sparsely furnished, but immaculate kitchen.

There were two doors within. One to the right was open to reveal a bedroom, bravely gay with flowered chintz that all too palpably dressed-up furniture fashioned of soap boxes. The door to the left was closed, and a padlock hung open from its staple. A rectangular table was spread with a white cloth, set for two. Ahead there was an icebox, painted a merry green, an iron sink no amount of painting could make attractive, and a gas range on whose top three covered pots stood.

"Which is the pot roast?" Doc Turner demanded, going straight to the stove. Joan reached it as soon as he, pointed to the largest of the aluminum vessels. The old man snatched off its lid.

"It's turned over," the girl said, "from the way I left it. Here's a fork for you."

The pharmacist felt it touch his fingers. He used it to turn the roast, and saw at once than an incision had been made in the bottom of the meat. He probed the slit with the tines, felt them grate on something metallic.

"It's here!" he cried, and scooped with the fork. The thing slipped, was caught again, came to the surface. It was a capsule of lead, such as is used to contain radioactive salts. It started to slide down the side of the grey roast, and Doc's fingers grabbed it...

"So nice." a voice hissed behind him. "Thank you very much."

Turner's arm jerked spasmodically, and there was a tiny scream from Joan. "Please make no noise," the voice said, "or I will regretfully be compelled to kill you. You, old man, please turn around slow with your hands away from your sides."

Andrew Turner complied. The laboratory door was open and in it stood a short, wiry figure. The man's clothing was of a peculiarly foreign cut. The wide-brim of his black felt hat was turned down to shadow the upper part of his face. His chin was square, his lips thread-thin and of a strange, bluish tinge. There was nothing either foreign or strange about the blunt automatic that snouted from an iron-steady hand, pointblank at Doc's midriff.

"Be so good," the precise, exotic English of the intruder sounded again, "as to give me what you have found in the pot. So sorry to trouble you."

The old druggist's mustache moved with a humorless smile. "Don't be so sorry," he said, calmly. "You won't trouble me. I can't give it to you. I've swallowed it."

The barrel of the automatic flicked. In the shadowed upper half of its owner's countenance there was a reptilian glitter, cruel and menacing. "So sorry," the man sighed. "That makes it necessary for me to take you where the formula can be recovered from inside you."

"What have you done with my Tom?" Joan's sudden cry was shrill, hysterical. "Where have you taken him?" She started forward, hands clawed, face frantic. The automatic flicked to her—

Doc grabbed her shoulder, dragged her back. "Joan!" he exclaimed. "You little fool. He could fill you full of lead before you got within a yard of him. That wouldn't help Tom any, would it?" His arm went around her waist and he held her quivering body close to him. "We've got to do exactly as he says. We haven't any choice."

He patted her.

The girl sobbed, and the squat man said, "Thank you very much. I would have disliked exceedingly to have to fill lady, like you say, full with lead. It is good advice you give her. I hope you follow it yourself."

Turner shrugged. "What else is there to do?"

"Nothing," was the grim reply, "except die. And I will tell you my gun is of a new kind. It will make no sound when it is fired, so do not count on bringing help by compelling me to fire it. You are armed, please?"

"No," Doc answered. "I am not."

"So. But just to make sure you will keep hands far away from sides as you go to door, and lady will stay two feet from you. Commence now, please."

"Come, Joan," the old druggist said gently, and started moving toward the entrance.

As he passed the spy, he heard the man pad softly away from where he had appeared, and was keenly conscious that he was following close behind. The light clicked out behind them as they went into the pitch blackness of the outer cellar.

"To the left," their captor directed. "We go out through the back."

DOC turned to the left, and dropped to his knees! He

twisted, reached eager hands to grab the legs of the spy. But a

garroting arm went around the old man's neck, under his chin,

squeezed, cut off his breath. A thumb dug excruciatingly into a

nerve-center under his scapula. Livid pain ran through Doc's

body, and he was numbed, helpless.

There was a hissing sound that might have been meant for a silent laugh. Then the spy's sibilant tones were saying, "So sorry you think I am foolish enough to take you out in dark without precaution." Then, "Release him, Number Seven. I think he has learned it is useless to attempt to escape us."

The strangling hold on Doc's throat relaxed, and the torturing thumb left off its pressure. Unseen hands, small but very strong, hauled him to his feet. He was stumbling forward again. Ahead, a door creaked open. The breeze that came in was cool, but it was laden with the garbage odor of the tenement house backyards. He was out in the open, the drab sky-glow over-arching him, sliced by a network of clotheslines.

Laughter, the high thin wail of a fretful baby, the noise of a family quarrel, came down from lighted windows. Joan's shadowy form moved ahead, someone beside her holding her arm, and there was someone beside Doc, too. Wood scraped on wood as a plank was removed in a back fence. The old man was guided through the aperture thus made; the board was replaced. The little group went across another backyard, and into another flat-house cellar.

Black lightlessness thumbed Doc Turner's eyes and lay clammy against his skin. He could hear Joan's faltering footfalls and the thud of his own stiff-kneed steps, but the progress of their captors was the faintest possible whisper of sound. A cat meowed, startlingly, next to his ear.

The feline yowl was answered from somewhere in the murk and then a widening oblong of paleness appeared. Directly ahead, shadows drifted across this, and then it was Doc's turn to go through. A door thudded softly shut behind him, and a bolt rattled into its socket.

A switch clicked, and light flooded a windowless chamber whose stone walls were mucid with damp and black-smeared with coal dust. "Tom!" Joan screamed and her cry was muffled at once by a gloved palm that slapped across her red lips.

TURNER was aware of the presence of men about him, but

his gaze was held by the one spread-eagled erect and flat against

the opposite wall, manacles stapled to the sweating foundation

stone cutting into the bleeding flesh of wrists, of ankles. Tom

Felton was naked. Muscles were knotted under a skin wealed by

crimson, angry burns. His head lolled forward on his chest,

saliva dribbling from the corners of his mouth, the young face

pasty and racked, even in unconsciousness, with the agony the

youth had endured.

Before the pharmacist had recovered from the shock of that sight, his own arms were lashed behind him, his ankles bound. He was thrown down on the ground and Joan was beside him, manhandled in the same manner but gagged.

A gabble of high-pitched conversation went on among the stocky individuals who had done this to them. Then the one who, by his behavior, was the leader, approached Doc.

"I am told you swallowed that which we desire," he purred. "Old man, do you not know that avails you nothing? An emetic is being prepared, and in three minutes you will spew it out."

Andrew Turner made no reply, gazing up into the malignance of those little eyes. There was curious mockery in that steady gaze of his. The spy chief's narrow brow wrinkled minutely, as with a puzzlement he dared not acknowledge even to himself. Then the hatted man who had appeared from within Felton's laboratory was kneeling beside Doc, a tumbler with a clouded liquid in it in his hand. Bruising fingers gouged the hinges of the pharmacist's jaw, forcing his mouth open. The liquid poured into it. The fingers moved to his nose, clamping the nostrils and compelling him to swallow.

The acrid solution reached Doc's stomach. After a moment he was very sick.

"It isn't there," he mocked his captors. "I lied. I didn't swallow the capsule. I turned on the gas. It was lit by the pilot, and I dropped the lead capsule in the flame. By now it is melted and the formula you are after is burned to ashes."

The three turned to him. The leader's lipless mouth was so tightly pressed that it melted into his sallow skin, and his resemblance to a reptile became perfect.

"So?" The hissing drawl of the spy finally ended that silence. "You think you have defeated Sarsin? So sorry to disappoint you, old man. The formula still exists, in the mind of its discoverer." His long-nailed fingers gestured to the hanging youth, apparently lifeless on the wall. "And we still can obtain it."

Doc's eyes drifted meaningfully to the ghastly scars on Tom's body. "You seem to have tried hard enough to do just that already," he said quietly, "without very much success."

Sarsin nodded. "I regret he was obdurate. But I believe we can now persuade him to speak. You seem to be versed in science. What we are about to do will interest you as an experiment in applied psychology." He clapped his hands, abruptly, and said something to his underlings in their own shrill language.

One of them darted to a box in the corner of the room, opened it, and fished something from it. When Doc saw what this was his old throat tightened on what he knew would be a useless cry of protest. The fellow—it was the one who'd frustrated his attempt to take advantage of the darkness in the other basement —came back to Felton, held a bottle under the youth's nose. Tom writhed, sputtered.

HIS eyes opened, and there was black horror in them. But

when they lit on Joan's form prostrate on the floor—the

sound that came from his gaping lips was a wordless moan in which

was pent the agony of a damned soul.

"Get your hands off her," Felton's rage-thickened voice shouted.

"Very beautiful," the spy chief murmured imperturbably. "It would pain me deeply to be compelled to destroy such loveliness." He looked up at Felton, his evil eyes questioning. "Especially, since it is so unnecessary. Come now. You have the choice between love of a country, that has permitted you to starve in a cellar, and love of the woman who has worked her fingers to the bone to feed both your body and your soul."

Felton stared at the woman he loved.

"Let me repeat," Sarsin went on, "the offer I made you. Twenty thousand dollars in cash, and a pension of five thousand a year for life—in exchange for your formula of an ointment that will permit the skin to breathe yet protect it against the corrosive gases for which no antidote has yet been found. Luxury for you and her, Thomas Felton, and an honored place in our land, to which you will come so that we can be sure you will not sell that secret of yours to another nation. Why do you hesitate?" the tempter continued.

"If you do," Tom choked out. "You will use those gases against innocent women and children, and they will die in agony."

"That is in the future, and uncertain."

Something in Tom's face told Doc he had come to a decision. His mouth opened. "All—"

Joan jerked out from under Sarsin's hands, jerked up to a sitting posture. Her bulging eyes pulled her husband's to them as with a physical grasp, and her head—her whole slim body—signaled to him. Signaled, plain as if she screamed it, "No!"

"No," Tom Felton groaned. "No, you fiend!"

Sarsin sighed. "So sorry you compel me to make you change your mind," he murmured. Abruptly in his hands was a length of thin wire. He looped this about Joan's white forehead, tightly, knotted the circlet closed with a pair of pliers. "We call this the 'Crown of Distress'," he murmured, "and it is very painful."

Tom's lips were compressed, but he was tugging at the manacles that held him—tugging till they lacerated his skin once again and were viscid with his blood.

Sarsin caught the knotted ends of the loop about Joan's brow in the jaws of his pliers. The other two spies held her so that she could not move. Sarsin's pliers twisted. The wire grooved the girl's skin, and her shriek was hardly muffled by the gag—

Then it was drowned by a thunderous crash of wood, by the squeal of bolt screws pulled from their fastenings. A red-orange streak of flame flashed across the room, and Sarsin collapsed queerly like a doll whose sawdust runs out of it. The other two leaped erect, went down again under the driving fists of two dark-clothed men who bounded into the room.

One of these dropped beside Joan, snatched at the pliers, was twisting loose the torturing wire still knotted about her forehead. The other, barrel-chested, carrot-haired, lunged toward Turner.

"Doc!" he cried. "Doc! Are you all right?"

THIS was the mechanic who had lounged in front of the

garage on Hogbund Lane, as the two had passed, not twenty minutes

ago. He was Jack Ransom, and he was Doc Turner's friend—his

good right hand in all his forays against the enemies of the poor

of Morris Street.

"Yes, Jack. But I thought you'd never get here," the old pharmacist said weakly. "I stalled for time in a half-dozen different ways, got them to work on me, attempted a fight I knew couldn't succeed, argued with them. But when you still didn't show up, I was sure you had missed my message."

"No, Doc. I saw you drop the carton of Black's cough medicine, as you passed," Jack explained. "I couldn't miss that—we'd used it so often as a signal between us. I read the address you'd penciled on it, and took right after you. But I bumped into Captain Morhard at the entrance to the basement where the Felton's lived. He was asking for them. I stopped for a minute to find out who he was and what he wanted, thinking that maybe he had a part in whatever trouble you were mixed up in. He got suspicious of me. We were both cagy, and, by the time we got straightened out and got into the cellar, the flat was empty."

"Who is he?" Doc asked.

"An army officer, from the Chemical Warfare Division," Jack said. "Felton had written to them, offering some invention, and he'd come to investigate."

"I see." Doc nodded.

"As soon as we got into the flat we knew something was deadly wrong, but we were dumber than hell," Jack went on. "We didn't pick up the trail you'd left, for a devil of a long time."

"You did find it, then—the sprinkling of salt from the shaker I snatched up from the table as I went past it?" Doc smiled. "It was on the side of me away from the spy, who was holding a gun and didn't see me do that. But I didn't dare start sifting it out till he turned out the light. I was outside the flat by that time."

"Yeah," Jack grinned ruefully, "and that's what held us up. I knew damned well you'd leave something for me to go by, but we ransacked the room before we thought of looking outside."

Doc's lashings were untied by now. He pushed Jack aside, rose to his feet. Captain Morhard had freed Tom. The youth, unable to stand, had sunk to the floor, but Joan was there to take his lacerated head in her lap—hold his torn body in her arms and bend over him. She was weeping, but there was a shining pride in her eyes.

Doc got to her, laid his hand on her shoulder. "This is the best doll of all, my dear," he said softly. "The doll that will bring joy and happiness to you all the rest of your life. May a doddering old man tell you that you have made him very happy by giving him the chance to fix that doll for you?"