RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

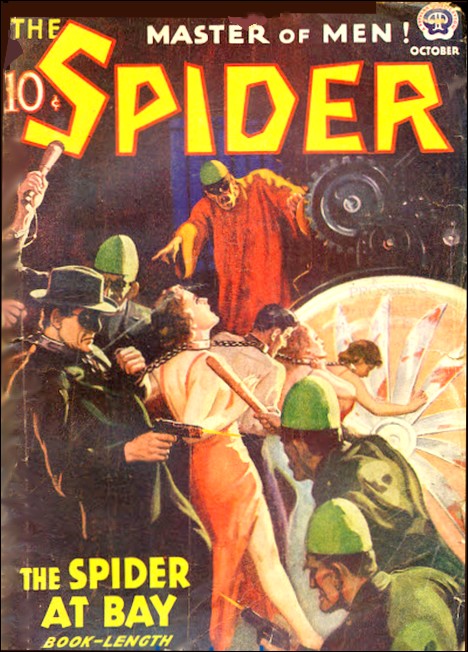

The Spider, October 1938, with "The Witness From Hell"

Into Doc Turner's little drugstore came the haunted man who wanted to cheat Death. Doc showed him how to do it and, at the same time, the way to pay back the big-shot who had sent him to a living hell!

THE man opened the door of the drugstore on Morris Street only far enough to let his scrawny frame squeeze in. He shut it at once on the noises of the slum thoroughfare; the raucous shouts of the pushcart peddlers, the polyglot chatter of aliens thronging the debris-strewn sidewalk, the rattle and pound of an "El" train. With a curious shambling swiftness, the man started back toward Andrew Turner, who was standing behind his sales counter at the rear of the store.

The man's feet made a strange rustling sound on the time-grayed wooden floor. Doc Turner had the fanciful thought that the stranger was a dried and empty husk blown between the glass-fronted showcases by some unfelt wind. Some wind of fear, by the jitter in the wrinkle-lidded eyes, by the quiver of the hands.

Frayed trouser-cuffs showed beneath the hem of a threadbare topcoat, and the shoes against which they rubbed were broken. A battered felt topped a face whose yellowish skin was drawn tight over bone. But some quality about the man told that this was no ordinary derelict spewed up out of the dark waters of poverty.

In the drugstore's grimy light it was difficult to determine wherein this lay, except that it might be in a certain refinement of his fleshless features, in the long sensitive slimness of his palsied fingers, in the shadow of pride and arrogance that somehow clung to the way he bore himself.

Turner had time only to note these matters, not to speculate about them, before the man arrived on the other side of the counter. His voice had the same dry rustle of dead leaves when he said, "If you will be good enough to show me some way to get out of here, unobserved from Morris Street, you will probably save my life."

From beneath white, beetling brows, Doc's eyes—their blue faded by his long years but their keenness of sight and human judgment undulled—caught and held the other's. Then, "Come around the end of this counter," Doc said. "Behind this partition is a door that opens on Hogbund Lane."

The man's sigh was an inhalation between thin colorless lips somehow sexless. He pushed at the counter to start into life again a body already at the limit of its endurance, moved in the direction the druggist had indicated.

Doc was before him at the doorway over which a fly-specked cardboard sign warned, Prescription Department—No Admittance. The pharmacist pulled aside the curtain that closed the aperture. The man went through it and Turner followed him into the back-room, was close behind him when he stumbled and caught at the edge of the long, white-scrubbed dispensing counter, close enough to see the look of agonized despair on his face as he slid down along the counter front to the floor.

All the man's desperate strength had run out of him in that gasping instant—all the stark will that had served instead of strength to keep him on his feet and moving.

As he lay quite still on the floor of the back-room, it was impossible to judge how old he was. There was a gray frosting on the hair uncovered by the hat that had rolled away, but this might have been caused by the terror with which it was evident he had dwelt a long time, rather than by age. Except for the netted lids, closed now, his face was unwrinkled, but so tightly drawn a skin might not show wrinkles at any time of life. He was emaciated, but this, like the yellowish pallor painting him with the hue of death, might be due to malnutrition rather than to the slow desiccation of the years.

The only thing about him of which Doc Turner could be certain was that this was a man deathly afraid...

THE druggist stooped to his strange visitor, straightened

again at the sound from outside of the Morris Street door opening

and closing, of heavy feet thudding across the floor. He snatched

a bottle from a shelf, wheeled, went out through the curtain past

the sales counter's end, met the newcomer halfway down the length

of the store.

"Good evening," Doc smiled, entirely self-possessed, though this man was squat, burly, his brown derby shadowing the swarthy, rock-jawed face of a thug. "What can I do for you?" Somewhere on the way the bottle had lost its cork, so that it looked as though the pharmacist, disturbed while measuring out its contents, had absentmindedly carried it out with him.

Spatulate, thick-nailed fingers flipped a lapel to afford Turner a glimpse of a nickeled badge. "I'm Inspector Carron of the Fire Prevention Bureau. I'm going to look over your premises back there."

"Indeed?" Doc murmured, reaching for Carron's lapel and folding it over. "At this time of night?" The badge was genuine, there could be no doubt of it, but the druggist had no doubt also that its wearer's interest in his back-room lay in the man who sprawled unconscious there and not in any conflict with the city ordinances. "After ten?"

"We're shorthanded and got to work overtime. What the hell's the diff to you?"

Doc tugged at his bushy white mustache, his fingers trembling. "I'm bothered all day by inspectors from all kinds of departments." A little stooped, a stained alpaca coat loose about his feeble-seeming frame, his thatch of silvery hair ruffled, he appeared a badgered old man whose tones grew querulous. "Board of health, board of pharmacy, income tax department, narcotic squad, labor inspector, city sales tax auditor—there's no end to them. And now the fire department shows up in the middle of the night." His voice crescendoed to shrillness. "I'm not going to allow it. I tell you I'm not going to allow it. You can just march out of here and come back tomorrow, at a reasonable time."

"Oh, yeah?" The inspector leered. "So you can cover up? What you got behind there you don't want me to see? A gas stove with a rubber-hose connection? A couple of five-gallon cans of benzene? I'm taking a gander behind that curtain, right now."

Turner's cry, "No you aren't," was interrupted by a sweep of the fellow's big-thewed arm. It jolted the old man aside, and that quite naturally splashed over the fire department man's sleeve the contents of the uncorked bottle Doc held.

"Look out!" Doc yelled shrilly. "Don't let that stuff touch your skin! It has! Good Lord! It has wet you already. Look!" He pointed a shaking finger at Carron's hand.

The skin on which the liquid had splashed was stained by a brilliant and terrifying yellow, spreading rapidly.

"Oh, my God!" the old druggist cried, snatching a handkerchief from his pocket. "If it reaches a ganglion...!" He was dabbing the handkerchief at Carron's hand with hysterical agitated clumsiness, but he was palpably careful not to let the liquid touch his own fingers. "And I haven't the antidote in the store."

"Get away from me," the fire inspector howled, his face pasty under its blue-black film of short hairs, his eyes goggling at the yellow plague that was eating his hand. "Get away with that damn bottle before you spill some more of it." He snatched Doc's handkerchief, elbowed him away, started wiping frantically.

Turner put the bottle on a showcase top, danced frenziedly about his victim. "Is it burning yet?" he shrilled. "Has it started burning you yet?"

"Burning?" Carron's thick-lips, blue-white, twitched. "It's burning hell out of me!"

"Oh, my heavens!" Doc's fingers went to his own mouth, jittered there. "It's gotten near the ganglion then—I'll call an ambulance. You've got to have treatment." He darted for the phone booth in the front of the store, got there, turned and came scuttling back. "Have you got a nickel? I've got to get a nickel to call the ambulance. Have you got—?"

"Hell!" the inspector gurgled, and was lurching for the door. "I'll get a taxi."

"Tell them it's Acidum Picricum," Doc screamed after him. "Tell them to use sodium thiophosphate. If only you're in time! You've got to hurry...!" The door slammed between him and the terror-stricken Carron, and then all Andrew Turner's excitement vanished.

"A little psychology is a wonderful thing," he muttered, his white mustache moving in a mocking smile. "Picric acid is used to relieve burns. In this strength it wouldn't irritate a baby's skin." Then the amusement was gone from his wrinkled face and he was moving back to the curtain that screened off his sanctum sanctorum.

OF all the restorative measures the old pharmacist had used,

the most efficacious seemed to be the bowl of hot savory soup for

which he'd sent a street gamin, and which stood now on his paper-cluttered desk—being slowly spooned by his patient.

The latter drained the last of it. "Now," Doc Turner said, "suppose you tell me what this is all about."

The frightened man raised his gaunt eyes to the old druggist. "I am profoundly grateful for all that you have done," he murmured. "But you will have to excuse me if I make no explanation. Quite frankly, I dare not." His hand was fumbling into a pocket of his worn trousers.

"You can trust me," the old pharmacist insisted. "I have owned this store more years than I care to recall, and I have been far more than a druggist to the people around here. I have fought for them against the wolves that prey on the helpless poor, and have helped them when they had given up all hope. You are terribly in need of help, and I will give it to you gladly, if you will permit me."

The man's hand came out of his pocket with a well-stuffed wallet. "I cannot adequately thank you for all that you have done for me." His effort at a smile was pathetic. "But you must allow me to pay for the materials you have used." The bill he extracted from the pocketbook was a ten. It was crisp, new-looking, but it was the old large size. There were many more like it in the worn pocketbook. "Please."

Doc made no move to take the money. "No," he said softly. "No thank you, Judge Garland."

The banknote fluttered from abruptly frozen fingers. The man was rigid, his eyes dilated and staring. Only his lips moved, the words coming from between them barely audible.

"How did you know?" he asked.

Turner tried to make his smile reassuring. "There was something hauntingly familiar about your face, around your forehead and eyes, but I couldn't place you. Naturally enough, since the newspaper pictures of you, when you disappeared, showed you full-faced, with a trim Vandyke and luxuriant black hair."

"I have changed in seven years."

"You have changed, too much to be recognized," Doc said. "You are well supplied with money yet you are ragged, and starved. That told me you'd been in hiding, afraid to steal from your covert even long enough to purchase the necessities of life."

"Afraid!" Garland whispered, his mouth twitching with agony.

"Your speech, your mannerisms, are too cultured for you to be any ordinary criminal," Doc went on. "The fact that the thug who came after you is a city employee argued some political reason for your hiding and your fear. But it was that banknote that gave me the final clue to your identity."

"That bill?"

"And the others like it in your wallet," Doc explained. "That size bills have been replaced by the smaller ones and have been out of circulation for a long time, yet yours are fresh and new looking. That meant you got them from a bank, and you must have gotten them at least five years ago."

Doc sighed. "You have been in hiding, then, something over five years, supplied with funds enough to last you all that time. There is a political tie-up with your concealment, and by your manner you must have been someone important. Six years ago there was an investigation in this city—a great scurrying to cover on the part of grafting politicians, a mayor resigning. That investigation failed because one man vanished, as though plucked out of space and time. He was a highly placed judge, and when he disappeared he was well supplied with money. He has never been heard of since, but never has there been any evidence of his death." Doc took a breath.

"You must be that man," he wound up.

Garland sighed. "Yes," he murmured. "I am that man. Once I sat on the bench robed in lustrous silk, respected and honored and envied. Now I am something less than human—a mangy, hungering dog hunted for my life. Hunted by the henchmen of the very one for whose sake I stripped myself of honor and of home!"

Doc Turner's voice was very gentle. "Why are you still hunted, Judge Garland, after so many years?"

Garland straightened in his chair, and something of dignity came back to him. "I will not tell you that, my friend. I will not cast over you the shadow of implacable death that has laid its black pall on me."

"Danger and death," the old pharmacist smiled, "mean nothing to me. I have had a good life, full measure and brimming over. If I were to lose it in one final effort to serve my fellow man it would matter to no one."

"It will matter a great deal," Garland countered, "to those out there." He gestured to the door, beside the desk, from beyond which came the muted voices of the slum. "Even in the dark depths where I have skulked, I have heard of Doc Turner—of how he is the poor's friend and more than friend, of how time and time again he has saved them from their folly and their ignorance. No. One like you is worth a hundred of me. I will not endanger you for my sake, for the sake of one in whom was placed the highest trust a people can give any man, and who betrayed it." His bony hands pressed on the surface of the desk, lifting him to his feet. "Even my presence here is a peril to you. I am going, Andrew Turner—"

"Wait!" In the older man's faded eyes there was a shining something that almost might be joy. "Wait! You need not tell me why your murder is sought. I know."

The other's gaunt face was mask-like. "You know?"

"Yes," Doc said. "Six years ago it was hinted that your disappearance saved from punishment the political boss who was primarily responsible for the corruption of the city. He laughed at the rumors, and continued on his way, untouched. A year ago, he was suddenly indicted on carefully guarded evidence. He was arrested, released on heavy bail. His lawyers have stalled for months, but he will be brought to trial next week, and the district attorney has stated that he will produce a single witness who will conclusively prove Frank Kelsey's guilt. You are that witness, and Kelsey is determined that you will never give testimony against him, testimony that you once vanished so that it might not be extracted from you. Am I right?"

Garland made a little gesture of defeat. "You are right. I took with me papers—orders to me as a judge, signed by Kelsey. I got word to the district attorney of what I had, promised to appear and produce the damning documents when they were needed. On the basis of this he started proceedings against the boss—Two days later an attempt was made to assassinate me!"

"Kelsey's men had found you!" Doc cried.

"Kelsey's men had found me, in a hiding place where I had been safe for five years," said the other. "There was only one way they could have located me—through a leak in the district attorney's office. By sheerest accident, I escaped. The months since then have been a nightmare of flight and pursuit. For a year I have hardly eaten, hardly slept. I have shivered in filthy, verminous rooms by day, in roadside ditches and in stifling sewer pipes. Under the cover of darkness I have skulked to new lairs, moving, always moving, lest someone might have recognized me and sent word to Kelsey. Just now I saw one of his men following me, and came in here."

"But why?" Doc exclaimed. "The district attorney would have kept your documents safely and provided you with a guard."

Garland's lips twitched bitterly. "One of his trusted men put Kelsey on my trail. It is not only Kelsey, but the whole structure of organized exploitation that is endangered by me and the papers I have. High officials of the administration, of the police, in league with gamblers, disorderly houses, racketeers. If they knew where the papers were, if they knew where I was, they would have found some way to destroy both. I hid the papers, but I dared trust no one with the secret of their hiding place, and so I must live." His voice rose to a thin-edged squeal. "I must live, I tell you, till I hear Frank Kelsey's jury pronounce the word, 'Guilty!' I must live...!" A gasp cut him off. Breath wheezed into his lungs. His face was livid...

"Good Lord, man!" Doc exclaimed. "You're sick!"

GARLAND'S hand fumbled for the chair from which he'd just

risen. Turner eased him into it, went to the shelves over the

prescription counter for a stimulant. He was back with it at

once, but, with an amazing display of the power of will over

human weakness, Judge Garland had recovered from the spasm.

A bitter smile twisted the thin man's face. "It won't get me till I have had my say on the witness stand. It can't. I won't let it."

"Heart." Turner said, his fingers on the other's pulse.

"Yes. I knew—a year ago—that I must soon die," Garland said. "That's why I turned on Kelsey and his gang. I'd saved them, and they'd forgotten me. Forgotten their promise to make it possible for me to return. I made up my mind to drag them down to where I was before I go."

The old pharmacist's faded eyes sought and held the other's, where a dark flame of pain flickered. "You lie," Doc said softly. "It was not personal enmity, nor the desire for revenge, that turned you against them. You lived among the poor. You saw their rents raised the dollar or two too much because of the exorbitant taxes the stealings of the gang made necessary, the prices of their food put beyond their reach by the demands of the racketeers Kelsey protects."

Doc went on. "You saw how they were mulcted of their hard-earned wages by the petty gambling games he makes possible. Perhaps you saw some fine, innocent girl debauched by the panderers for the vice syndicates with whom he works. You learned that the graft on which he fattens are, in the final analysis, dividends from human misery. You knew that you could not face your Maker until you had done what you could to right the wrong you had helped to create."

Garland's bloodless hand opened and closed, opened and closed, on the desktop. "You believe that?" he whispered.

"It is the truth," Doc said. "That is why I stopped you when you wanted to go out of here, why I kept you here when every minute you remain means that my danger is so much the greater. Not for your sake, John Garland, but for the sake of those for whom at long last you are fighting. I have fought for them all my life, and it is my right to join this fight for them too."

"But you are not needed—" the other began.

"I am needed, and you know it," Doc said. "You know that even if you escape the killers who hunt you, the killer inside of you may get you—tonight, tomorrow—and Kelsey will go free again to continue feeding on those people out there, on my people. Another shock, a few more incidents of such excitement as you have just passed through, your heart will stop, and the knowledge in your brain of where those documents are will be blotted out forever."

Doc nodded. "I am no physician, Judge Garland, but I can tell you that if you live to take the stand against Frank Kelsey, it will be a miracle."

"What—what can I do?"

"Share your secret with me," Doc advised. "Then your death will not mean so much. Tell me where you've hidden the letters that will convict Kelsey. You know you can trust me."

Garland's lids narrowed, and his mouth tightened. There was a moment of throbbing silence, and then, "Yes. I can trust you. They are—"

"Wait!" Doc Turner interrupted. "Don't say it. Write it down. I am old and forgetful." He pushed a paper and pencil into the other's hand. "Write it."

The man obeyed.

Doc took the scribbled-on scrap. "Now," he said. "I'll mix you a drink that will give you strength to get away from here, far away." He turned back to his dispensing table, lifted down a wide-necked glass container from the shelves. A clear, watery liquid glinted within this. The druggist twisted out the stopper.

"You don't have to bother with that," Carron's voice said. "Garland isn't going anywhere."

THE old pharmacist's head turned. The fire inspector had just

come through the curtain from the front. His lifted hand was

stained a bright yellow, but the revolver in it was a dark

metallic blue, its muzzle awkwardly elongated by a silencer.

The corners of Carron's mouth turned upward in a grin that held no humor. "Good trick you pulled on me," he snarled. "They sure had the laugh on me at the hospital. But didn't you figure I'd be back?"

"No," Doc murmured. "I thought that you would be sure I'd hustled our friend away as soon as you got out of the store. I thought the safest place for him would be to stay here."

"A sort of chess game." This did not come from Carron. Another man had stepped through the doorway, taller, broader of shoulder, his hair a rust sprinkled with gray, but cast in the same brutal mold. "Only you didn't count on the right opponent—"

"Kelsey!" The name was choked from between Garland's livid lips. "Frank Kelsey."

He was rising out of his chair, stiffly, mechanically, as though it were some involuntary contraction of the muscles that lifted him. "You—"

"Me, John. It's a long time since we got together."

"A long—time." The thin man was erect now, rigid, something soldierly about his bearing, something proud.

"But I've caught up with you at last." The smile on Kelsey's lips was feline, cruel. "At last, John."

"No," Garland gasped. "No, Frank. You have not—caught up —with..." And he toppled forward, rigid, so that there was still that soldierly stiffness about him when he had thumped the floor and lay there, unmoving.

"Cripes," Carron groaned. "He's passed out."

"Out and far away," Doc Turner murmured. "To a place where you will never find him. To a place where his tortured soul will find eternal rest. Are you satisfied, Frank Kelsey? He will not testify against you."

The russet-haired man stood staring at the body on the floor, and he did not appear to have heard what was said to him.

"Look, boss," Carron said. "Maybe he ain't dead. Maybe we ought to make sure."

Kelsey stirred. "He's dead, Dan. He'll never be deader. Look. We were born on the same block and went to the same school. He was always the bright boy of the class, and I was the one who fought the bullies who tried to beat him up. He never forgot it. I quit schooling when we got our diplomas, and he went on through high school and college and law school. When he was admitted, I was leader of my district. I offered to help him. He wouldn't take it, but he was always on tap when I needed him. He didn't even know it was me made him a judge, till he was sworn in and I told him."

He went on. "He couldn't get out of doing me favors then, because he wasn't built to forget a debt. They were only little ones at first, but they kept getting bigger. Then, once, I got him to change the records on a case, with his initials, and I had him where I wanted him."

Kelsey nodded. "I used him after that—used him plenty —and I was so sure of him I got careless. Then the Newberry probe came along, and he could have turned on me, but he didn't. All the rats were running for cover, but John Garland stuck by me. He gave up his job—he gave up everything to save me. That's the kind of man he was."

He asked, "So what did I do? I let him go. I never tried to help him. And when he turned up again with the goods he had on me, I hounded him to his death. That, Dan Carron, is the kind of dog I am."

"Gee, boss. You don't want to talk like that," Carron said. "You had to go through for the guys that's played with you. You couldn't help yourself."

"No," Kelsey sighed. "I can't help myself. I've got to keep on being a dog." His jaw hardened and his eyes lifted from the dead man on the floor, found Doc. "So, Mister Druggist, I'll have to ask you to hand over the paper he wrote out for you."

"You were listening," Turner said.

"We were listening out there for a long time," Kelsey admitted. "I was hoping that he would tell you aloud where my letters were, and that we wouldn't have to come in on him at all. I knew he had a rotten heart and what seeing me would be likely to do to it. I had ordered him bumped because I didn't see any other way out of it—but now I thought I did. No jury would believe him, without the papers to back him up, but the papers will convict me and rip the town wide open without him. So—I'll take the slip on which he wrote where they are."

"I can't give it to you," Doc replied.

"You mean you won't."

"I mean I can't." Doc held up the wide-mouthed bottle that he'd opened just before the two had showed themselves. It had a label of white glass, and the black letters on the label said Sulphuric Acid. The liquid in it was no longer water clear. It had turned a muddy brown, and dark brown flakes were floating around in it. "There is a peephole in the partition on which these shelves are fastened," Doc went on. "I saw you out there, through it, and I dropped the slip in this acid just as you came in. These flakes you see are all that is left of it."

KELSEY'S thick lips went the bluish color that Garland's had

during his heart attack, and his knobby countenance was dark with

fury. But his voice was steady as he said, "Still playing chess,

eh—and you think you have me stumped? But I've got another

move. You read what John wrote, and so you know where those

letters are."

"I read what he wrote," Doc agreed. "But that doesn't do you any good. If you were listening, you heard me tell the judge that I am an old man and forget very easily."

"You?" The russet-haired man's tone was very calm. "You lie by the clock. If you couldn't remember what was on that paper, you would not have burned it up."

"What's the difference, boss," Carron put in, "where those letters are? Nobody knows it now except this bozo. If I plug him, they'll rot there." His gun listed, avidly.

"The hell they will," Kelsey grunted. "Somebody will turn them up, sometime. I don't want to worry about them the rest of my life. I want to know they're gone, and, by all that's holy, I intend to. Are you going to tell me what you know, old man, or do I have to make you?"

"Do you think you can make me?" Turner asked quietly. He was still an old man, and feeble, but there was about him now a sort of enduring hardness, an unconquerable strength, that was of something other than flesh and could not be weakened by the years. "Do you really think you can?"

"Damned right, I can," Kelsey snapped, and started prowling toward Doc, his big jaw thrust forward, his simian arms held a little out from his sides, their fingers curled. "I'll tear it out of you with your guts."

The bottle in Turner's hand swept back—splintered into fragments, the acid glutting down over the counter.

"He was going to throw it in your eyes!" Carron howled. "He was going to throw the acid in your eyes—if I hadn't clipped the bottle with a bullet. Now will you let me bump him?"

"Like hell," the other grated, leaping forward. His fist smashed into Doc's narrow chest, slammed him away from the counter and into the desk. "Like hell you'll plug him before I beat that information out of him." Kelsey took the other stride that brought him looming above the lolling old man.

There was a little blood at the corner of Turner's mouth, but his eyes were undaunted. "Beat away." There was not the faintest quiver in his low tone. "The harder the better."

Kelsey raised his fist again, but Carron's voice held it. "Listen, boss. That won't do no good. You can slug him till he's cold, and you won't get anything out of him. I know his kind."

The fist dropped again, slowly. "You're right," its owner muttered. "And that's what he's after. Thanks Dan. We'll try something different."

"What?"

"You'll see," Kelsey said. "But we can't do it here. There's a switchbox behind you. Turn out the store lights from it. We're going to take him to Garcia's."

Little lights glinted in Carron's eyes. "Geez, boss," he exclaimed. "That Spik's a devil—"

"And it's a devil's tricks we need. Go on. Do what I say. It's late enough so the people outside will think he's closing up."

Carron turned. There was a click, and darkness flowed in. Then, in that darkness, there was the thud of feet going across the store floor. The three shadowy forms reached the pharmacy door, went out through it. Doc Turner was between the two burly men, and they were close to him—so that it seemed as if he were going somewhere with two friends.

"Lock the door," Kelsey whispered.

The druggist turned to obey. The few hucksters left along the curb, the peddler with his laces hung over his arm who shuffled toward the three, could not see the revolver in Carron's pocket, its muzzle jammed against Doc's side.

"Bargains," the peddler whined, coming up to them. "Look—handwork. Cheap." He held out his stock in trade to Kelsey.

"Don't want any," the latter growled. "Beat it."

The bearded man turned to Carron. "Cheap," he wailed. "Such bargains, believe me, I wouldn't give to my own father if it wasn't so late." His nasal twang rose. "Die momseren nehmen unser freund mit ah pistole."

[Yiddish: "The bastards are holding our friend up with a pistol."]

The grimy fingers of his free hand took hold of Carron's sleeve, "Look, mister," and pulled him away from Doc with sudden strength, while the laces, wadded, were slammed against the telltale bump in the inspector's pocket.

There was a muffled pop. The bunched laces jumped away with the impact of the bullet they muffled. Kelsey's fist thudded against the side of the peddler's face, sent him sprawling. A pushcart rolled across the sidewalk, slammed into the big man's midriff. Oranges, grapefruit, onions, pelted the two brute-jawed men, hurled by hucksters who had been rallied by the peddler's cry, in Yiddish, "The devils are taking away our friend with a pistol."

Bruised and battered by the vegetable shower, Carron managed to drag out his revolver, but a weazened little Italian leaped in to wrench it from his hand before he could fire it. A watermelon thumped Kelsey's knees, swept them out from under him. A jute bag of potatoes, effective as any sandbag, bludgeoned him into insensibility. A rock-hard salami sausage performed the same office for his henchman. The fight was over.

"THANKS, my friends," Doc Turner smiled to the grinning aliens

who had come to his rescue. "That was good work. I hoped that if

I could get them to bring me out here, you'd know something was

wrong by my not greeting you as I always did. But for a while, I

didn't think I could get them to do it."

"No." The lace-peddler shrugged. "What then? If our Doc Turner don't say 'hello' when he sees me coming, then I must right away know it's something the matter. But we must call right away a policeman before they wake up."

"No," the old pharmacist said. "I can't have the police mixed in this." Half the force, at least, were subservient to Kelsey or one of his fellow leaders. "There is danger in calling them in. We'll put them in Tony's pushcart, cover them up with potatoes and take them off to the basement where you men keep your wagons overnight."

"Anything what you say." The little Italian who had disarmed Carron agreed. "You just tell us what we do, and we do it."

"I know you will. I know that you are my friends."

"And why not?" A blond German ejaculated. "Is it not that you are the best friend from all of us?"

FRANK KELSEY came to at the rear of a dim cellar aromatic with

the fruits and vegetables piled on the pushcarts that filled it.

He lay prone on a bed of jute bags, bound hand and foot with

bailing wire, and Dan Carron, similarly treated, lay beside

him.

"Awake, Kelsey?" Doc Turner was standing over him.

"Yeah," the boss growled. "I'm awake."

"That's fine," Doc chuckled. "Because I wanted to tell you about some moves in that chess game we played—some moves you didn't know about. The one, for instance, of my seeing you through that peephole in the partition when I went to get the stimulant for Garland the first time, not the second. I knew you were there, and I knew you would never let him get away alive. That's why I worked so hard to get him to tell me where the letters were hidden, and why I didn't let him tell it to me aloud."

"So that's why you were ready with the sulphuric acid?" Kelsey scowled. "I thought it queer that you could get it out so quick."

"Yes, that is why." Doc said. "That was mate, Kelsey. And now I'll tell you the last move. You're going to stay here, bound as you are, and gagged, while I get those letters from where Garland hid them. Then I'm going to take them to the office of the Daily Globe, where I'll have them photostatted under pledge of secrecy, and the negatives sworn to, before I deliver them to the district attorney. Too bad poor Garland didn't think of that way of making sure of their safety. Checkmate, Kelsey?"

"Checkmate," the big man acknowledged with a groan.