RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

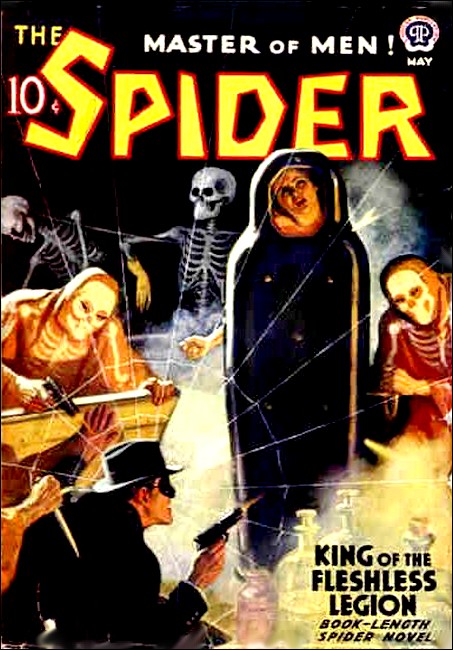

The Spider, May 1939, with "Graves Filled to Order"

It was a strange vigil that Doc Turner kept—a fiendish funeral set for the witching hour. But Doc's business was saving people, not burying them—and he acted fast to thwart the world's most inhuman mortician!

THERE was tragedy in the face of the young woman—fear in her eyes and also a stark courage that overrode fear. But what had first drawn Doc Turner's attention to her was the almost grotesque incongruity of her attire and mien here on Morris Street.

For nearly an hour she had been standing at the front of his ancient pharmacy, her back against a corner of the telephone booth. In all that time she had hardly moved at all, her slim body rigid, her gloved hands clutching a black suede pocketbook, with a strange fierceness.

Out there on Morris Street, naked electric bulbs made vivid with their garish blaze the scarlet and emerald and gold of fruits and vegetables piled high on pushcarts. Swarthy, sweatered hucksters raucously shouted their wares; shawled housewives pinched pulp and bargained; tattered urchins hawked market bags and shoelaces and dirty-wrappered candies, and unshaven, collarless laborers shuffled wearily, burly shoulders stooped under their burden of unending, hopeless toil.

Within Doc's store were a bare wooden floor rutted by the traffic of long years, dingy showcases, sagging shelves—a frail old druggist whose hair and bushy mustache were silken white, blue eyes faded, skin dry and almost transparent over fleshless bones. Utterly out of place in these surroundings was this woman of about thirty, sleek in a cloak of the finest broadcloth, her small feet sheathed in lustrous leather artfully molded, around her graceful throat a stole of silver fox fur, thick, soft and lustrous.

Her features were clean-cut and tiny—perfect as a chiseled cameo. Glowing, tawny hair peeped from beneath the edge of a modish hat whose price would probably have fed a Morris Street family for a month. Doc, fumbling with some pyramided boxes on the sales counter at the rear of the store peered covertly at her. What was she doing here? For what was she waiting?

Despite the tensity of terror that gripped her, something in the way she held herself spoke of the habit of command, of the habit of being served and protected from harshness. There was about her an aura of warm, dim lights, of soft music, of costly perfumes. Therefore it was all the more puzzling that, in her cheeks' downy velvet, a tiny muscle now twitched endlessly, and her little head was thrown back stiffly erect in an attitude of desperate defiance...

A phone bell shrilled! The woman's red lips gaped as though she were about to scream, but instantly she spun around and dived into the booth. The knifing trill cut off with the rattle of the receiver being snatched from its hook.

"Yes?" Her voice had an oddly penetrating quality that brought it to Doc, clear and distinct above the brawl outside. "Yes, this is the Payer." Her arm reached out of the booth. Her gloved hand took hold of its door handle, and the door rumbled shut.

A strange thing to say, the old pharmacist thought, his acid-stained fingers drumming the counter edge. It wasn't her name. She had said the Payer. That sounded like a password, to assure the caller that it was she and no one else who responded to the ring on that public 'phone.

But why shouldn't she give her name, here where no one could possibly know her? Her first name, at least... It was no intrigue that had brought her here to await that call. No woman would come to a tryst with fear in her eyes. No lover would need a countersign to identify his sweetheart's voice. Whatever her business was, it was none of Doc's! She wasn't one of the people of Morris Street to whom he was cicerone and friend, for whom he so often had fought the mean and vicious criminals who prey on the helpless poor. If she needed help, she could purchase it....

SHE was coming out of the booth. She hesitated, turned to Doc,

came toward him, grayness under her artfully applied rouge, her

under lip caught by white teeth. She reached the counter.

"Please—" her voice was low, husky—"can you direct me to Potato Alley?"

"I can, Miss." Good Lord! Potato Alley was a narrow passage running behind the water-front warehouses. Its shanties were infested by hoboes, cutthroats, the dregs of humanity. "But I hope you don't intend to go there." It was a refuge of riffraff, avoided by all decent people, avoided even by the police. "Not alone. Not all dressed up like that."

"Why not?" she asked.

"They'd cut your throat there for the fur that's around it," Doc told her. "You'd be safer in the jungle."

Her eyes widened, fear a black flame in their depths, but there was quiet, unalterable determination in her response. "Nevertheless, I must go there. Where...?"

"Myra!" a man's exclamation cut across her sentence. "Myra!"

She spun around. "Jim!" He was tall, powerfully built, but grey showed under his black Homburg at the temples, and there was a faint tracery of wrinkles on his big-boned, rock-jawed face. "Jim!" she cried, going across the floor to him. "Where did you drop from? I thought you were in St. Louis." Her fingers gripped the lapels of his dark Chesterfield coat. "Oh, Jim, I'm so glad you're back!" In her tone there was no longer any hint of the fear that had gripped her.

"The negotiations in St. Louis took only half the time I'd expected. I didn't wire that I was coming home, hoping to surprise my little wife." His hands, strong and capable, were cupped under Myra's elbows, and his deep-set grey eyes devoured her hungrily. "I discover that she's gone gallivanting." His smile was a bit shamefaced. "I couldn't wait—I went hunting for you."

"Jim!" The way she said the name made it a caress. "You really didn't think you'd find me in the hall sewing shirts for you, like Ulysses found his Penelope." Her laugh was a silvery tinkle. "But how ever did you manage to find me?"

"I phoned the garage and George was back," he said. "He told me that he'd driven you to the Morris Street Settlement House, that you'd ordered him to pick you up there at midnight. When I got to that place they didn't know you by name. But I described you and some dirty-faced brats remembered that you'd been there a while and had gone out. You weren't exactly inconspicuous in that mob of foreigners out there, you know—so a very little questioning enabled me to trace you here."

"You're marvelous, Jim! You should be a detective—"

"I need to be, trying to keep track of you," he said. "I didn't know you were interested in settlement work."

"Oh, Laura Anders told me how thrilling it was, and I thought I'd look into it while you were away. Jim! The very first thing, I heard about a family that's simply starving and too proud to go on relief or take charity. When I said I wanted to do something for them, somebody said this nice old druggist might have an idea how I could help. So I came down here to talk to him, and he's promised to help me. You did—" she twisted around to Doc Turner—"didn't you?" Abruptly there was agonized appeal in her eyes. "You'll take care of it for me, won't you? Promise?"

"Yes," Doc said. "I promise." It would not have been Doc if he had not responded to that desperate plea, though in the next moment he was berating himself for an old fool.

"Oh, thank you," Myra gasped. "And you won't give away our little secret, will you? My life will be simply ruined if you do." It sounded like the extravagant chatter of a feather-brained socialite, but the old druggist knew it was meant in deadly earnest. "I'm sure I can trust you. Oh—I'm being terribly rude, aren't I? This is my husband, Mr. Turner. Jim Mowrie."

Jim Mowrie. James Wellington Mowrie! That name was known to every reader of the newspapers. He was a financial tycoon, and—Doc recalled the flip comment in the gossip columns—about a year ago he had wed an actress fifteen years his junior.

"It's a pleasure to meet you, sir," said Doc. "Your wife and I have had a long and interesting talk about the problems of my people."

Myra Mowrie was an actress. That explained how she had been able so swiftly to mask the emotion that shook her, how she had been able to lie so glibly, so deftly to convey her hidden appeal for Doc's aid and his silence.

"Suppose you two let me in on what this is all about," Mowrie was saying. "I'd like to—"

"No, Jim," Myra cut in sharply. "You have your own charities, let me have this one for myself. Come on. Let's go somewhere and celebrate. Let's go to the Ritz-Plaza. I hear that Davin Fitch has a wonderful new routine of naughty ballads." She was tugging at his arm, and he was going out of the store with her. "Good-night, Mr. Turner," she said over the silver-speckled black of her fur. "I trust you. I'll call you soon, to hear what you've done."

And then the door had closed behind them, and Doc was muttering. "What I've done! What am I supposed to do for you? How do you expect me to know?" His hand made a little gesture of exasperation—and touched something soft and bulky on the counter, something that had not been there before.

He looked down. It was the pocket-book of black suede Myra Mowrie had clutched to herself so fiercely. She had forgotten it....

HE picked it up, started to go around the end of the counter,

to call her back—then stopped. No. He had realized that she

hadn't forgotten the bag. It had been behind the pyramid

of cough drop boxes that stood beside the cash register. She had

thrust it there, in the instant his attention had been distracted

by her husband's exclamation, in that split-second hiding it from

James Mowrie and leaving it for Doc to find.

The answer, then, to his question must be within this smooth leather. All he had to do was open its platinum clasp.

Not out here, though. Caution, inbred in the old pharmacist by his years of strife with the disciples of evil, warned him to take it through the curtained doorway in the partition behind him. In the concealment of the prescription room that was more home to him than his cheerless furnished bedchamber on Hogbund Lane, he tugged at the fastening.

It came free. The bag sprang open and out on the scrubbed-white wood of the long prescription table spilled a flashing diamond bracelet; a pendant of green fire, a pear-shaped emerald large as the end of his thumb; an opal glowing with the embers of secret passion; globules of frozen foam that were matched pearls an empress might envy.

They lay there, jewels worth a fortune, splintering dingy luminance into all the splendors of the spectrum. Doc Turner gaped at them, his jaws dropping, his eyes bulging. This was mad. It was utterly beyond the bounds of belief. It wasn't—it couldn't be—true that wealth such as this should have been thrust on him, impulsively, without explanation.

And then he saw that the corner of a paper, grey-white; harsh-textured paper like that from a child's penny pad; protruded from the pocketbook in his numbed fingers. He pulled it out, stuffed the jewels back into the bag, fastened its clasp and unfolded the sheet.

Smudged, soft pencil had been used to print words crudely on the grey paper—startling words. He read:

We've got the monkey. It will cost you thirty thousand to get her back. Get it and be in Turners' Drugstore on Morris Street between ten and eleven tonight. When phone in booth rings answer this is the Payer and you will be told what next.

Come alone and don't have nobody trailing you or you won't here no phone and you won't see her no more. We got her grave all dug. She will be in it at midnight if you don't show or if you call the cops or mark the bills—or try any other tricks.

Come ready to give because we ain't trying no more contacts. This is a one shot gamble and the stakes is the monkey's life.

Doc read the first sentence again. "We've got the monkey." The

thing was still utterly mad. What monkey could be worth thirty

thousand dollars to anyone? How could the peril of a pet animal

bring such terror to a woman's face? By what unimaginable

circumstance could her husband's knowledge of its loss ruin her

life?

Mad the set-up might be, but Myra Mowrie was altogether sane. The fear in her eyes, the agony in them when she had pleaded with him for help, had been damnably real. What then...?

Blackness suddenly crashed into Doc Turner's skull! He went spinning down into a dizzy oblivion....

THE first thing he was aware of, as he returned to

consciousness, was the throb of pain in his head. His fingers

fumbled to the back of his scalp, where the pain centered, felt a

bump. He'd been struck there, then. Blackjacked by someone who

had stolen up behind him as he was engrossed in that

letter—

The letter! Recollection stirred Doc. He thrust hands against the floor where he lay, lifted. He was on his feet and he was staring at the prescription counter. It was bare. The black suede bag was gone! The jewels that were in it were gone!

The letter also was gone. It must have been plucked from his fingers as he went down. Everything that Myra Mowrie had left him had vanished.

She had left him those things for a purpose. "You'll help me?" she had asked, anguished appeal in her eyes, "I promise," he'd answered. She had meant him to take the jewels to Potato Alley, to buy back with them the monkey that weirdly meant so much to her. "I trust you." With a secret that exposed would ruin her life! With a fortune in jewels...

Never in his long years had Andrew Turner betrayed a trust. He might have decided to get hold of the woman, secretly, return the gems to her and wash his hands of the whole insane business. But now he could not. She would not believe his story, and even if she did, there was still the damning fact that she had trusted him with a fortune and by his carelessness he had lost it.

He should have realized, on his first reading of the note, that the woman was being watched from outside the store by someone who knew what wealth there was in the black suede bag. "Come alone—or you won't here no phone." He should have realized that the watcher would see that she had left without it. He should at once have taken precautions against exactly what happened.

Another phrase in the extortion note came back to him, a frightening phrase. "We got her grave all dug and she will be in it at midnight if you don't show..."

Doc Turner fumbled a thick, old-fashioned gold watch out of his vest pocket, pressed the spring that caused its cover to fly open, stared at it. Seventeen minutes past eleven. Abruptly his seamed countenance was hard, granite-textured, his faded blue eyes no longer kindly but bleak, relentless....

AT eleven-twenty-five a stooped old man in a shabby topcoat, a

battered felt crushed down over silken white hair, hesitated

before a dark slit between two towering, windowless water-front

warehouses. There was a small package in his hand, string-wrapped, a label pasted over the string. He held this package up

to catch the pallid luminance of a distant street-lamp, peered

near-sightedly at it as if to make sure of the address. Then he

slipped into the maw of Potato Alley.

A miasma of rotted debris assailed Doc Turner's nostrils, of decaying fruit grown overripe in storage and discarded. Chill through his clothing struck the dampness of these depths where the sun never penetrated. Then he was out of the passage. But the stench was still with him, and the dank chill, and mingled with them the fetor of diseased human bodies.

To his left, black and macabre under the brooding glow of the city's night-sky, a half-dozen ramshackle wooden structures lined a narrow, cobbled areaway that was walled on his right by the topless, Stygian loom of the warehouses' rears. Doc sighed, recalling when these gaunt, shattered wrecks were white-painted and shining, when this cobbled expanse was a row of fragrant gardens, when green lawns sloped down to a sparkling river.

Now there was darkness here, and vague shadows that skulked within the darkness, seeking deeper shadows at the advent of a stranger. Here and there along the dilapidated fronts of the old houses was a thread of yellow brightness that signaled light behind drawn shades. But no door was open, no sound of merriment came from within these blind, forbidding facades.

The old man ambled to the nearest, climbed three creaking stairs on to a sagging porch, rapped on a paintless door, waited. There was a curious scuttering within, as of rats disturbed and dispersing to their holes. Then a shambling shuffle neared, and a cracked, shrill voice was lifted on the other side of the drab panel.

"Who's there?" it demanded. "Who's knocking?"

"Doc Turner, the druggist from Morris Street." His reply was loud, much louder than necessary to penetrate the thin wood. "Open up, will you?"

Somewhere nearby a window scraped up, and Doc had the curious tingling sensation of eyes upon him. "Hurry," he cried. "Don't keep me waiting."

Within the house there was a bass rumble, and then a bolt was rattling metallically. Vertical light was slitting the darkness in front of Doc. The slit was widening, was revealing a crone bent almost double, her twisted body covered with a dirt-grey, shapeless garment, black eyes small and fierce in a nut-cracker face.

"What you want?" she asked.

"Here's the medicine the vet ordered," Doc said. "Get busy—"

"Medicine! We ain't ordered no medicine here."

"You didn't! Isn't this Number One, Potato Alley?" Doc waited.

"Sure it is. But nobody in our family's sick—"

"I know nobody in your family. This is for the monkey, woman," Doc insisted. "Stop fooling—"

"Monkey! Say, are you nuts!" demanded the woman. "We ain't got no monkey."

"Oh, good Lord!" Doc seemed taken aback. "The vet must have given me the wrong address. Who has a monkey in the Alley? Quick, woman, tell me! I have got to get this to them in a hurry, or—"

"Nobody has, that I know of. Hey," she shrilled out into the darkness. "Who's got a monkey? Anybody seen a monkey around here?" There was an odd murmuring in the night, but no answer. "You see, mister," the hag said, "there ain't no—"

"But there is," Doc said. "The vet didn't know their name but he couldn't be mistaken about its being here in the alley, even if he did get the wrong number. Look here. They're hiding it, and you've got to help me find it. In a hurry too. You've—"

"Do your own finding, mister," sounded in Doc's ear, harsh, gruff. A man, burly, brute-jawed, had appeared beside him from nowhere. "Get me?"

"I can't." Doc twisted to him, his voice rising in excitement. "I haven't got time. Where's the nearest phone? I've got to call the police, get them here to go through every house. That's the only way it can be done quick enough—"

"You'll bring no cops to Potato Alley, mister." The fellow's fingers were clutching his arm, digging in, bruising. "And you won't try if you know what's healthy for you."

"Healthy!" The old druggist was laughing, the sound high-pitched, hysterical. "That's funny. That's very funny." The laugh cut off. "Listen, you fool. If that monkey isn't found in half an hour—if she doesn't get this stuff pumped into her—there won't be one of you in Potato Alley that will be healthy. You'll be dying like flies—"

"Dying! What the blazes are you talking about?" said the man.

"Just this, if you've got to know," Doc told him. "That monkey has had lepulitis angorica for thirty-three hours. If it doesn't get an injection right away, the disease will turn into smallpox and it will spread through the alley like wildfire. Now do you understand why I've got to get the police to find—"

"Damn the police," the man cut in. "We'll find that lousy monkey for you." He let go of Doc, wheeled to face outward. "Hear that, everybody?" he yelled. "Find a monkey that's hid somewheres in the alley. Find it quick or you'll all be kickin' off like a bunch of roaches that's been sprayed with arsenic. Bring it here when you find it, and bring the guy that owns it here too, an' we'll take care of the both of 'em. Find 'em an' bring 'em here before we all get smallpox—"

"Smallpox!" a woman's voice screeched. "Oh, blessed Mary..." And then Potato Alley was suddenly alive with sounds, the thud of running feet, darting shadowy forms in the shadows—with a growing, angry mutter of sound that was all the more vicious, ominous, because it was muted, blanketed by the fetid night.

ALMOST stamped out as the dread pest is, its name still

conveys the terror of a festering death. Tell these people that

there was a murderer among them, and they would laugh and hide

him from you. Tell them you are looking for a criminal who has

opened the floodgates of a dam or set fire to half a city and

they would cheer him, their mouths drooling with anticipation of

the loot that will be theirs. But tell them someone has brought

pestilence among them, and they will hunt him down, ravening.

They will find him for you, and tear him limb from limb...

A form loomed out of the darkness, came upon the porch. "Listen, Hammer Fist," a low voice said to Turner's companion. "I know where that monk is. I'll take the doc to him so he can fix him up." The druggist couldn't make out the face of the speaker but he was very tall, and so thin as to be cadaverous.

"The hell you will, Gouger," Hammer Fist grunted. "Bring it here, and the guy that owns it."

"All right," Gouger muttered, "if you want it that way. But I got a notion the ape's had that lepu—whatever it is, longer than the owner told the vet. Maybe it's turned into smallpox already. I thought if the doc took a look at it—"

"Yeah. You're right. The doc better go look at it first. Go on." The simian-jawed fellow turned to the pharmacist. "Go on with Gouger."

"Very well," Doc replied. "But you ought to come along. The people who endangered you all should be punished."

"No. Gosh, no. Me go near that... Aw, Gouger won't let them get away. I got to—I got to call everybody off. Go on." There was a sudden threat in Hammer Fist's voice. "Are you going or do I have to make you?"

Doc shrugged. "I'll go," he consented. There wasn't anything else to do. He'd sowed a wind and if he refused, he would reap a whirlwind.

"It's down this way," the thin man said, and they were descending the porch steps together. "We go along the warehouse wall, here." He was walking so close to Doc their sides touched, and there was something small and hard pressing into the old man's ribs. "That's a gun you feel," Gouger said, low-toned, "and if you yelp it will go off. I should have hit you harder in the back of your store," he said bitterly. "I should have cracked your skull."

"Yes," Doc Turner sighed. "You should have, for your own good." Were they going all the way to the other end of the alley, he wondered. Was that where the grave was that was to be filled at midnight? The sounds of the search he had stirred up were subsiding.

"Lepulitis angorica," Gouger muttered. "That's a good one. Did you have it figured out before you got here, or did you make it up on the spur of the moment?"

"I was prepared with the story," Doc said quietly. "I knew the only way of finding you in this sanctuary of criminals was to fool its denizens themselves into looking for you. If I'd brought the police your neighbors would have helped to hide you, and it would take the whole force weeks of search to unearth you. But all I wanted was to get hold of the monkey. Why don't you give her to me? You have the jewels, and that was what you wanted. If you murder me, you'll be hunted by the cops. I'm too well known around here to vanish without a search being made for me."

"Wait till you see the monkey and you'll know why we can't give her to you," said Gouger. "You'll know why we weren't going to give her to Myra Mowrie—why the lady herself was never going to get out of here alive. Stop here." They weren't quite to the end of the warehouse, but a high pile of something—they looked like broken boxes—hid them from the rest of the alley. "Bend down and put your hands on the ground. You'll feel an iron plate. That's a trapdoor. Feel around till you find a ring and pull up on it."

Doc obeyed.

"It will be covered over again with cobbles by morning," Gouger's voice murmured above him. "Nobody will ever know it was here. But they would have found it tonight, with all the riot you stirred up, and I wasn't quite ready." The iron plate hinged up and out of the blacker dark it uncovered gusted a peculiar odor.

The old druggist sniffed. "Stale and moldy mash," he identified it. "This leads to the cellar of the old brewery, then."

"Yes. The rest of the building has been turned into a warehouse for textiles, but the basement is too damp to store them there. Go on down."

THERE were stone steps under Doc's feet, steps slippery with

fungi. The trapdoor thudded down overhead and instantly light

sprang from behind him—light of a hand torch that laid his

long, black shadow on the green-scummed steps he was

descending.

"You speak like an educated man," Doc said. "I thought you were that. The misspellings in the note were obvious."

"I have a couple of degrees." The steps ended at a level, earthen floor. The flashlight beam pushed darkness back into arched recesses formed by heavy stone pillars, by a vaulted low roof. "Keep going."

A thinner vertical column grew out of the murk, a pipe of some kind. It was blobbed, near the floor, by something curiously formed. The light brightened on this, and helpless wrath swelled Doc's throat as he saw what it was.

"Let me introduce you to 'the Monkey'," Gouger chuckled. "You see why I couldn't give her to you in exchange for the jewels. She knows me and would talk."

It was no ape that was lashed to that pipe, bound and gagged. It was a little girl of about seven! Rumpled locks framed a thin, cameo face, a head wearily drooped. Mercifully the eyes were closed! The girl was asleep or unconscious.

"'The Monkey' was the pet name her mother had for her, and no one but little Janey and Myra knew it," Gouger explained, imperturbably. "When Myra read that name in the note, it assured her that the writer must have gotten it from the child. Clever, wasn't it?"

"Satan is clever too," the old man gritted, between clenched teeth. The flashlight's shaft had moved a little and he was looking at an oblong ditch in the ground, a ditch just big enough to accommodate a seven-year-old's body. The excavated earth was piled beside the grave, and a shovel was thrust into it.

"Yes, that is the grave into which Janey was to go at midnight," Gouger confirmed his thought. "It will have to be made larger now. Take hold of that shovel and start digging."

Doc turned.

His fingers were plucking nervously at the package he had held on to all this time, was tearing the paper from it in small shreds. "You may make a getaway, but you can't be sure that you haven't left traces that will put them on your trail. Even if the police give up trying to track you down, James Mowrie never will. I'm a good judge of character. He's got the pertinacity of a bulldog, and he's head over heels in love with his wife. He'll use all his wealth to hunt you down. He'll offer a reward no fence will ignore. The first time you try to cash in one of those jewels, you'll be caught.

"Let me take the child and go. I promise you that I'll see to it that you will not be bothered. There's a bargain."

"No," Gouger said. "The answer is no, because I don't have to rely on your promise. Myra Mowrie will not send the police here. She does not want to lose her husband as well as her jewels and her child. That's what has made this little adventure of mine so safe, except for your interference."

The thin man chuckled. "It's very simple. James Mowrie is Myra's second husband, but he doesn't know it. He doesn't know that he is a stepfather. Myra's first husband was a chorus boy, poor as a church mouse. It would have hurt her drawing power on the stage to have it known that she was married and a mother. She kept it a secret. Even when Janey's father died, Myra kept the fact that she had been married a secret. She never told James Mowrie that she had a daughter in a boarding school up in Maine. But I knew all about it because I was her first husband's friend in the old days. Yesterday I called at that school with a forged letter from her mother, to take Janey away for a long visit. James Mowrie may love her, but he's a hard man, and he'll stop loving her if he ever finds out how she deceived him.

"She doesn't dare let him know. She didn't dare ask him for the ransom money. That's why she brought the jewels instead, all the pretty jewels he's given her."

"That, old man, is why I don't have to trade with you. Why the story of Janey Sutton, and of Druggist Turner, will end in that grave. Enough. Pick up that shovel and start digging."

"No!" Doc was no longer stooped.

"As you wish," the man beside the flashlight yielded. "I'll make it larger myself. But you'll go into it alive, in that case, with your knees smashed by lead." His gun-barrel drifted lower to aim at the old man's thin shanks—

Doc's hands darted out in front of him. The bottle in them, from which he'd torn the wrapper that alone had corked it, vomited a glinting, colorless liquid straight into the Gouger's face. Doc leaped aside in the same instant—leaped out of the jetting, orange-red spray from the kidnapper's gun.

Through the reverberated thunder of that blast a scream shrilled, "My eyes! Oh, God! My eyes...!" The gun blasted again. Doc had his hands on the shovel, was springing with it into the very nucleus of that random but lethal spray. There was a sickening crunch, a dull thud on the earthen floor. The pungent, tear-bringing fumes of ammonia...

"Mama!" a child's frightened cry.

"It's all right, Janey. It's all right, Monkey. I'm going to take you to your mother."

As Doc untied the lashings from around the little form he was thinking. "Now I will have to make that grave larger." And then, "There must be a way out of here through the front of the cellar. I won't have to go through Potato Alley again." Jewels flashed in the beam of a hand-torch.

THE pushcarts were gone from Morris Street when the taxi

Andrew Turner had hailed drove up in front of his store and

stopped. The garish lights and the alien-eyed throngs were gone,

and there was only the pale luminance of a street lamp to throw

its beams on the plate glass windows of his ancient pharmacy.

"We'll go inside here, Janey," Doc explained, "and telephone your mother to come for you." He got down on the sidewalk, turned to help the little girl out—

"Janey!" A sudden rush thrust him aside. "Monkey!" Myra Mowrie was in front of him. She had the little girl in her arms. "Oh, Monkey," she sobbed. "I never thought I'd see you again."

Fatigue welled up in the old pharmacist. His legs were giving way. He swayed.

"Steady," a deep voice said. "Steady, my friend," the voice came from James Mowrie.

The surprise shocked Doc back to some semblance of strength. "You..."

"Yes, my friend, she brought me," said Mowrie. "She couldn't fool me. I saw that she was terribly upset over something, terribly worried. I finally got the truth out of her, hurried here. Your store was closed. I was just starting out for Potato Alley when you drove up."

"You were starting? Then you—"

"I love Myra, old man. She was a very foolish young woman not to know how much I love her, how much I always will love her. Why shouldn't I love her daughter too? My daughter now..."

Doc Turner couldn't fight off the swirling mists of weariness any longer. As he settled, sighing, a limp, frail form in James Mowrie's strong arms, there was a smile on his wrinkled old face—a smile of happiness that all his terrible fatigue could not erase.