RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

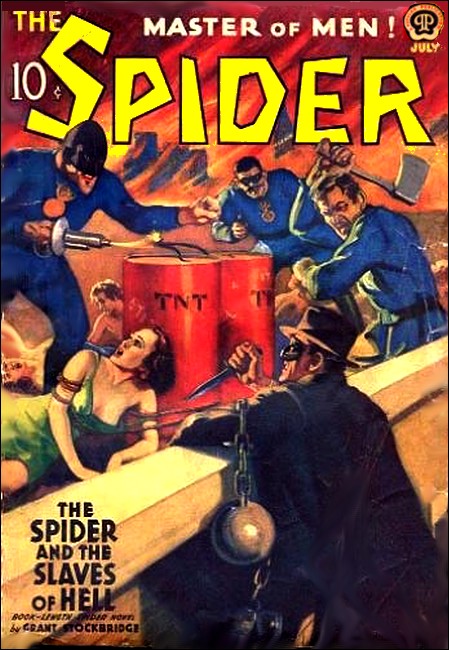

The Spider, July 1939, with "Congratulations to the Corpse"

They had gathered together to celebrate in his honor—those tenement dwellers whom Doc Turner had long bravely defended against the Underworld. But not one of the merrymakers had the slightest idea that their chief guest was already being fêted by a toastmaster from hell!

SOMETHING unusual was brewing on Morris Street. Standing white-haired and frail-seeming in the doorway of his ancient pharmacy, Andrew Turner sensed the excitement that motivated the shifting throngs. There was a strange new ring to the raucous shouts of the hucksters whose pushcarts made vivid splashes of color in the dusk. Furtive whispering passed among the shawled housewives, among the swarthy, alien-countenanced laborers plodding homeward from their day's weary toil. Even the tattered, dirty-faced urchins took time out from their play to huddle in low-voiced conferences, little eyes darting furtively as if to make sure that they were not overheard.

"I don't like it." Doc Turner's acid-stained, fleshless fingers tugged at the bushy droop of his mustache. "Jack, my boy, I don't like it at all."

"Hell, Doc!" Jack Ransom shrugged burly shoulders, a broad grin on his freckle-sprayed countenance. "You're always looking for something to worry about." Carrot-topped, barrel-chested, the sturdy young garage mechanic spoke confidently. "There's nothing wrong. I'm sure of it."

"The Lord knows I hope so,—" Doc sighed. "But tomorrow morning I shall have been dealing with these people for fifty years, and I ought to know when something's exciting them."

"Fifty years, huh!" An odd twinkle suddenly came into Ransom's brown eyes. "That's a long time."

"A very long time," the old druggist agreed. "Morris Street was little more than a country road when I opened this store. Those tenements—" he waved a hand at the dingy facades—"were all shiny and new. Instead of these iron 'El' pillars, elms marched along here, tall and proud. One breathed the fragrance of flowers from the stately homes whose lawns sloped down to the river, instead of this stench of over-ripe vegetables, of unwashed bodies and clothing worn too long."

"Yes," Ransom murmured. "You've told me about that."

"Then the 'El' came to roof Morris Street with shadow and with noise, and those lovely houses down by the river gave place to factories and warehouses. And the immigrants flocked here, from every quarter of the world." Doc sighed. "They dreamed of streets paved with gold, and found only granite cobbles; of a bright, new life, and found only toil and bitter struggle; of a brotherly welcome, and found themselves only despised as outlanders, scorned for their bewilderment and their helplessness."

"But they found you too, Doc,"—Jack added. "And in you they found a damned good friend. That faded sign overhead only says that you're a druggist. Yet you've been far more than a druggist to them. You've helped them in a thousand ways; advised them. Dozens of times you've risked your life fighting for them against those lousiest of crooks—the ones that prey on the ignorance and superstition and friendlessness of the poor. And these people know it. Don't make any mistake, they know it and love you for it.

"Perhaps so," the old man demurred. "But they haven't yet learned to come to me as soon as some new trouble shows up. You've been my good right hand, Jack, in most of my battles for them, and you're aware how clannishly secretive they are. Time and again we've found out only by accident that they were being victimized. Time and again we've had to fight their enemies in the dark—and because of that have more than once come uncomfortably near the brink of death."

"Yeah," Jack grunted. "They sure are hellish close-mouthed."

"And something is happening right now," Doc fretted. "I can't get anything out of them, but I'm not fooled. They're all worked up, and—"

Jack interrupted. "I tell you you're wrong this time. The neighborhood has been quiet lately, and you're overworking your imagination... But I've got to beat it, Doc. I have a date."

"With Ann, of course."—A tender smile came into the faded blue of the old eyes. "I suppose you two will be getting married very soon, now that she's back from her trip to the Coast."—Doc Turner's staunch old heart was big enough to embrace all the teeming slum, but there was a very special corner of it for Ann Fawley, the elfin-faced granddaughter of the maiden he had loved and lost in that long-ago when the world was young. "Was that the secret she was bubbling over with when she came in to see me this morning?"

"Maybe." Jack's response was enigmatic; an odd evasiveness characterized his manner. "Well, I'll be seeing you." He swaggered away and, his hat cocked jauntily askew on his orange-red thatch, was lost in the crowd.

DOC turned back into his dim and dusty store. He went slowly

past the old-fashioned, heavy-framed showcases, the sagging

shelves that once had been painted white but were now a dingy

yellow. Beyond the wooden sales counter that cut across the rear

was a partition in which a curtained doorway had been cut. As the

old man went through this into his rear office, his smile faded,

and worry returned.

"Whatever Jack says," he muttered, taking a mortar and pestle from a shelf over the sink, "there's something queer in the wind. Now, I wonder what they're all so worked up about..."

The powders that he then started to compound had been weighed, divided, folded and placed in a box with meticulous neatness and Doc was pasting the label on the prescription, when stumbling footfalls from out front, and a racking cough, summoned him to wait on a customer.

The man was hatless, and beneath his three-day stubble of beard there was yellowish, unhealthy pallor. His cough seemed to be tearing him apart. Despite the warmth of the evening, the collar of his threadbare jacket was turned up. His hands, ingrained with dirt, clutched its frayed edges closely about his neck. He reached the sales counter, hung there, while that terrible cough went on and on.

Turner patiently waited for it to stop. He was accustomed to these derelicts who wandered in here from the waterfront, seeking to purchase with a panhandled dime some rubbing alcohol out of which they hoped to stew the denaturant so as to make it barely drinkable. Dregs of humanity...

Abruptly, Doc started. He had glimpsed the man's eyes. Deep-sunken in blue-shadowed sockets, they were not bleared and rheum-rimmed as was usual with his kind. They were clear, and in their dark depths, the old druggist read a scream of agony!

"That spasm's tearing you to pieces!" he exclaimed. He reached down to a shelf under the counter-top, plucked a small bottle. "A couple of drops of this in water will stop it. I'll get—"

"No," the derelict croaked through his cough. Knotting muscles ridged his jaw, swelled tautly in his hollow cheeks. The knuckles of the hands that clutched together the rusty-black fabric at his throat whitened with strain. Breath pulled in between those livid lips and made an odd, rattling sound. "Listen..."

A pulse throbbed in Doc's temple.

The man's jacket was soaking wet where he held it so desperately, and something red was seeping through his fingers. "Call Starling Twelve-o-six..." He was getting out the words with infinite effort. "Tell... Reynolds... it's set back to... eleven-thirty. He knows... place." The furrowed brow was drenched with sweat. "For God's sake, talk to... no one else. Police... nor... anyone..."

The derelict rolled along the counter edge. His hands dropped numbly from his throat and his coat fell open, revealed a bright scarlet shirt...

Not a shirt! It was naked flesh, painted with blood that oozed out of a deep knife-cut raking downward from the base of the neck! The man slid off the counter, fell with a dull thud to which there somehow was a dreadful finality.

"Starling Twelve-o-six," Doc repeated, as he flung himself around the counter. Something familiar about that number...

He dropped to his knees beside the sprawled form. There was no scream now in those sunken eyes any longer, nor sight. There was no pulse in the pathetically thin wrist. But the bloodless mouth was smiling—distinctly it was smiling. It was as if by sheer power of will alone the bedraggled outcast had held life in that tortured body just long enough to deliver his message—and then had yielded it up gladly.

"Starling Twelve-o-six." Turner recalled it now. He'd used it not long ago, when he located a kidnapper for whom the nation was hunting. It was the phone number of the local office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

"What's up, Doc?" The pharmacist's head jerked around at the voice. A burly policeman was striding in. "What..." The cop broke off. "I see—you need an ambulance."

"No," Doc said, rising. "The morgue wagon."

"All over, eh? Gawd, but he's carved!" The officer swung around as there came a sudden rush of feet. "Scram!" Men, women, a couple of youngsters were crowding in, morbidly curious. Reluctantly they gave back before the cop's waving arms, his threatening club. "G'wan, beat it before I start fanning you!" Jabbering, squealing, he got them out of the store, closed and bolted the door.

"Bunch of hyenas," he growled. "Hell, Doc! No use giving the phone company a nickel." His banana-like fingers closed on Turner's arm, pulled him out of the booth. "This is an official call, and it's free if I give the operator my badge number." He pushed in.

Doc looked on disconsolately. This was the only phone in the store, and he couldn't go out to use another. There was the crowd flattening noses against the door's plate-glass panel, for one thing. A more compelling reason was the secrecy the dead man had enjoined on him. "For God's sake," he had croaked, "talk to no one else... Police, nor anyone." He'd used his last breath to say that.

The cop remarked, waiting for his connection, "I saw the bum reeling in here. 'Higher than a kite,' I says to myself. 'I better drop in and make sure Doc ain't having no trouble with him, this night of all...' Hello, Sarge! Rafferty calling. I got a stiff in Turner's."

Doc turned away from the booth, glanced up at the cracked dial of a pendulum clock that hung on the sidewall of the corner window. The rusted hands pointed to eight-fifty. The message to Reynolds had concerned something that was to occur at eleven-thirty. Over two hours remained until then, but in minutes now the store would swarm with police officers, detectives, an assistant from the medical examiner's office... Doc was familiar with their ways. They would ask him innumerable questions. It might be a long time before he could telephone, unobserved. No telling, also, how much notice the F. B. I. agents might need for whatever it was this dying man's message portended...

Was the very manner of the seeming derelict's death to defeat the purpose for which he had so heroically sacrificed himself? The pharmacist threw a swift glance at the stiffening body on the floor, shambled behind the showcases near which it lay. Then he did a queer thing. From a shelf he took a faded blue carton labeled Nastin's Coughex, went to the display window and put it in front of a pyramid of mothball boxes...

A gong clamored outside, and blue uniforms forged through the crowd. "Here they are!" Rafferty exclaimed, opening the door to admit the first of the city's police officials.

IT was past ten before the pathetic body had been removed and

its epitaph blithely pronounced by the departing Rafferty. "Just

another bum on his way to Potter's Field." Then Doc darted to the

phone booth, dropped his nickel in the slot.

Public telephones in a neighborhood such as this are not supplied with dials. The operator asked, "Number, please?" and Turner answered, "Starling One-two-o-six." He heard a click, then the booth door suddenly rolled open and something hard prodded his back.

"If you want to live," a soft, silky voice directed, "say 'wrong number' and hang up." The enunciation was too precise to be an American's.

Doc's skin crawled as the receiver said, "Department of Justice."

The hard thing nudged his spine.

Doc decided.

"Wrong number," the old druggist answered. He hung up, asked, of the booth-wall he faced, "What next?"

A hand patted his sides, reached around and felt his chest for a shoulder-holstered gun. "You are not armed," the low tones noted. "That is good. I shall, in a moment, place my own automatic in my pocket, but it will remain trained on you. Please remember that I shall fire at your first sign of recalcitrance. Do you comprehend?"

"It's hardly difficult to understand," Doc said dryly.

"I shall not miss," went on the voice. "I should not have missed had I been compelled to shoot you down through the mail-slit in the door. The police officer saved your life when he prevented you from entering this booth, right after he had driven me out of here with the others. Close against the glass panel, I have been watching you ever since. I know that you have had no opportunity to telephone that Starling number." The icy grimness with which this was being said was fully as ominous as the dull feel of the gun barrel in Doc Turner's back. "Had you attempted it, I should have slain you, and myself, if my escape really were cut off."

"You might still have to do that," Doc said. "If I yelled for help, right now, a hundred people who love me would hear my cry. They wouldn't let you get away."

"But you will not call for help. Because, Mr. Turner, you know that if you do, you will die uselessly—for you will not have communicated the message that has been entrusted to you. However, all this conversation is futile. I am now about to pocket my weapon. As soon as I do so, you will turn, slowly, and come out of this booth. Bear yourself so that any casual observer will believe us to be merely chatting amiably. You may address me as Gerson—Richard Gerson."

The pressure was released from Doc's spine. He came about leisurely, stepped from the cubicle.

The man was only a little taller than Doc himself. His long, narrow face showed beneath a black homburg; sharp, chisel-bridged nose, waxed black mustache, thin chin. The black eyes were gimlet points, piercing. Expressionless though it was, there was death in that countenance. A light topcoat, black and vaguely foreign in cut, fell loosely from his narrow shoulders. His right hand was thrust into a pocket of that coat with apparent negligence, but the pocket was bulged with something more than a hand.

Through the open door came the thunder of an "El" train, the roar of traffic, the hoarse shouts of the hucksters, the shrill, alien jabber of the sidewalk throngs. Out there on Morris Street was all the swarming life of the slum. In here was only that low murmuring voice of death.

Doc asked, "What do you want of me?"

"Your silence. And I intend to make certain of it."

Turner's white eyebrows arched. "Indeed? May I ask how?"

"By having you accompany me to where it can be assured," said the man. "You will close your store in exactly the manner you are accustomed to do, then stroll away from here with me. Whether you will be permitted to return depends entirely on your own compliance with my orders."

Doc knew that last statement to be a lie. Gerson had no intention of leaving him alive to furnish the F. B. I. with any clues to the killers who had murdered one of their men. However, no hint of this conviction was in Doc's response.

He sighed. "But doesn't it occur to you that my closing up so early might arouse questions?"

The other smiled thinly. "It is well after half-past ten. You have often closed as early as that, on dull nights."

"Never when I have had a prescription to be called for, as I have now, on the counter in back."

Gerson's eyes narrowed. "You can send it out by messenger, can you not? Call one of those brats outside, have him deliver it. I shall be close enough to you to hear every word you say."

Doc made a little gesture of defeat. "All right."

HE turned to the door just in time to see a gangling youth

enter, a youngster of about sixteen with kinky black hair, a

hooked promontory of a nose, thick lips that broadened in a smile

as he spied the old pharmacist.

"Abe!" Turner exclaimed, "Abe Ginsburg! Good Lord, Abe, I swear you've grown a foot since your family moved away and you stopped working for me."

"You haven't changed even one little bit, Mister Turner." Abe's eyes sparkled as he shook hands with his former employer. "And the store, it is just the same?"

"Abe used to be my errand boy," Turner explained to Gerson, but he didn't say in how many of his adventures the youngster had been an invaluable aid. "I haven't been able to afford another."

"Perhaps you won't need one, if our business goes as I've outlined." There was warning in the sharp, black eyes. "You recall what I said." The pocket-hidden hand moved a little, and Doc's veins chilled. He'd lived long enough. It didn't matter much if he died tonight. But that message to the F.B.I....

"I came in to say hello," Abe was saying. "But I see that you are busy. I'll go talk to some of the fellers from the old block and come back later."

"I'm afraid I won't be here later, Abe," Doc said. "I've got to close up now and go somewhere with this gentleman. But you can do me a favor, if you will. I was just going to see if I could get a boy to deliver some medicine."

"Sure," Abe exclaimed, as Gerson gave an imperceptible nod of approval. "Sure thing. Just like old times, it will be."

"Yes, Abe. Just like old times." A muscle was twitching in Doc's cheek. "Come in back while I wrap it up."

Not only his ex-errand boy followed the white-haired pharmacist to the rear of the store and through the curtained doorway in the prescription room partition—but also the man who was waiting to take Doc to his death.

Doc worked.

The box of powders he had just finished labeling when the derelict's entrance called him away, still lay on the long, white-scrubbed compounding table. His fingers steady, Turner got out a manila envelope from a drawer, put the box in it and licked the flap closed. "It's for Mrs. Achtung, Abe," he said. "On Hogbund Lane. The number—"

"Sure, Mister Turner," the boy interrupted. "I ain't forgot it. I ain't forgot nothing from the time when I worked here. You don't have to tell me any more."

"All right, then," Doc nodded, handing the package to him. "Thank you." He shook hands with Abe. "I hope I'll see you again soon." The boy went out, and the druggist turned wearily to the expressionless Gerson. "Do you approve?" he asked.

The latter smiled his thin and deadly smile. "If I had not," he purred, "my automatic would have so indicated. But let us go quickly, before we are again interrupted."

Doc took his worn hat from the hook. He turned out the prescription-room light, shambled out front and switched off all lights except a single small bulb that hung by a cord over the cash register. The two went out, and Doc closed the front door.

"My motor is around the corner," Gerson said. "You will at least not have to walk to where you are going."

Andrew Turner's key clicked over in its lock. Every night for fifty years he had locked this store, exactly like this. Was this the last time?

The pushcarts were gone early tonight, he noticed. Gerson walked so close to him that he could feel the man's gun muzzle against his side. Around the corner the big black limousine was waiting in the dimness of the tenement-lined street.

"It looks like a hearse," Doc remarked, smiling at his feeble jest. From somewhere in the night the melancholy strokes of a tower clock came to his ears. It was exactly eleven...

THERE was too much gaiety and confusion for that tower clock's

booming to be heard within the walls of the Crescent Casino, two

blocks up Morris Street from Turner's Drugstore. The huge, barn-like

ballroom was rapidly filling with the men and women of the

slum, now a bit uncomfortable in their Sunday best, but faces

shining with happiness.

Ann Fawley, slim and lithe, her eyes two shining stars, stood near the door to greet the arrivals. This swarthy Croatian was Anton Czerno, between whom and crucifixion by fanatic Penitentes Doc Turner had once intervened; this skull-capped and bearded little Hebrew was the shochet Israel Lapidus who, but for Doc, would have been the victim of a Golem—a monstrous corpse-thing seemingly informed with evil life by a more evil necromancer.

"Glad you could come," Ann cried to Sasha and Maria Feodorovna, one-time prey of terror from across the seas. Tim Flanagan was next, Morris Street liquor dealer whose best gin had once turned pink and supplied the clue that led Andrew Turner to the hideout of the wielder of a murder-torch that was spreading panic through the slum.

A dozen girls arrived together, their bargain-basement finery gay as their chatter. Workers from the Super-Clean Laundry these, once prospective victims of a lethal insurance racket that Doc had squelched. A delegation of saffron-countenanced Chinese shrilled greetings, their leader Yang Su—the name of whose twelve-year-old son the white-haired druggist had kept from being inscribed on the Scroll of a Thousand Tortures.

Poles and Letts and Syrians, they streamed into the hall —Hebrews and Slavs, Italians and Czechs. Each owed his life, happiness to the frail old man whose diploma merely recorded that he was a pharmacist. Negroes, menaced once by a Voodoo papaloi, mingled with Pennsylvania Dutch whose Hex-woman's chicanery had been more than matched by the druggist's science. The roll was endless...

They streamed in and scattered among long, white-covered tables that groaned under a load of queer-smelling viands, odd-looking cakes, and fruits and beverages that might well have served as an Exposition of the Foods of the World. Right-angled to these was another, smaller table elevated on a dais, and on this rested a huge white cake serried with fifty little candles.

Bunting and banners festooned the great hall. They radiated from a white streamer blazoned with scarlet letters:

FIFTY YEARS MORE, DOC TURNER TO PROCLAIM THE REASON

FOR THE GATHERING—THE REASON FOR THE EXCITEMENT

THAT FOR A WEEK HAD CHARACTERIZED MORRIS STREET "EL."

Not only denizens of Morris Street were in this happy

celebration. Garden Avenue, three blocks to the West, was the

abode of the rich, but even from here had come beneficiaries of

the old druggist's crime battles. This grey-haired little woman

with snapping eyes was Martha O'Neill, to whom he had restored a

daughter lost for many years. This portly banker owed the life of

a son to Doc, and here were Jim and Myra Mowrie; Paul Melior,

subway contractor whose laborers once were being decimated by a

ruthless competitor, when Doc stepped in...

Of all his people, Doc loved the children best—little Daphne Papalous, orphaned by a nightmare of torture and murder; Leo Bernstein whom a fiend called Astaris had once brought to the brink of suicide; Yang Toy; Janey Mowrie; Ted, straight-backed boy whose skin still bore the marks of the child-slaver's whip from which Andrew Turner had rescued him.

Tonight all had come to do Doc honor...

Jack Ransom, freckled face alight, said to Ann, "Everything's all set, sweetheart. Isn't it time I went over to the store and started wangling Doc into closing up?"

The girl pursed her full lips. "I think so, Jack. Are you sure you can get him over here without his suspecting what's up?"

"Dead right, I'm sure. I'm going to ask him to help me make arrangements for our wedding. That will bring him. But you had better make sure there's no one hanging around the door to tip him off that something's up."

"Abe Ginsburg was supposed to do that, Jack," she said. "I wonder why he hasn't shown up yet."

"Ah, Abe's up to his old tricks," Jack said. "Stopped in Eisenberg's Delicatessen Store for what he calls a nosh, I guess. He'll get here. All right, honey. I'm on my way."

THE grin faded from Jack's face as he came near enough to

Turner's drugstore to see that it was already darkened, lifeless.

"Hell!" he exclaimed. "He's shut up already. Now I've got to go

over to his house and rout him out." He broke into a run, hoping

against hope that he could still catch the old man before he left

the shop.

Then he stopped short. "God!" He was staring at the corner display window, his lips suddenly color-drained.

Light from a street lamp illumined the contents of the window so that the carrot-topped youth could see the advertising signs it contained, the pyramids of mothball boxes—

And the faded-blue carton labeled Nastin's Coughex!

"He needed me," Jack Ransom groaned, "and I wasn't around." That box was an old familiar signal to him—a signal that there was danger in the wind and the circumstances such that Doc could get a message to him no other way. It was their agreement that Jack should keep an eye opened for it. "He needed help, and I was too busy fixing up a party for him to answer..."

THE black sedan moved toward the river at a leisurely pace.

Luminance from a street lamp filtered in and showed Andrew Turner

the sharp, saturnine face of Gerson sitting alongside him in the

back seat. The driver was merely a dark, bullet-headed

silhouette.

The two were talking in some language Doc did not understand. However, their conversation did not so engross Gerson as to distract attention from his prisoner. The unintelligible chatter ended, and he said, in his strangely precise English, "My colleague wished to destroy you unceremoniously, but I argued that the difficulty of disposing of your body might delay us. We have decided to take you to our leader and leave the decision to him."

"What is this all about?" Doc asked.

"I regret that I am not permitted to answer any questions."

The car reached the wide waterfront street, turned into it. Deserted, silent pier fronts were on one side; tall warehouses, their windows steel-shuttered and blind, on the other. The huge portals of the piers were closed, but in their dark embrasures sprawled darker forms—derelicts, such as the knifed man had appeared to be, sunken in degraded sleep.

Gerson indicated them with his free hand. "The individual who involved you in this affair cleverly pretended to be one of those. Only by a very lucky accident we discovered that. He counterfeited a drunken stupor as his ear was pressed to the receiving disk of a listening device. He had somehow managed to conceal the microphone where it could eavesdrop on our most confidential conversations."

"Why didn't you shoot him?"

"A knife would attract less attention," was the answer. "A corpse stabbed to death in this vicinity is not so unusual as to stir up much troublesome investigation. Like those of every nation, your police are realists. Unfortunately the person deputed to wield that knife was clumsy. The man, though mortally wounded, got away from him and... but here we are."

The car's headlights had flicked off.

"These are our lookouts," Gerson murmured, referring to a couple of apparent vagrants who slouched in the corners of the entrance they approached. "We slipped up in not having the wharves on either side of this one covered."

The great door was opening noiselessly, revealing only darkness within.

Gerson said something to the driver. "We will wait here for instructions," he told Doc.

Turner's eyes had accommodated themselves to the darkness now. Against the lighter screen of the pier's open end he saw the chauffeur's barely distinguishable shape rise, get out of the car. The fellow left the door open, and Doc could hear his footfalls die away. Then a yellow slit cut the darkness in the direction he had gone, widened and became a doorway. Across this the chauffeur was momentarily silhouetted, then vanished.

"This structure is not being used for its intended purposes at present," Gerson explained, "but we found the pier-master's office well adapted for our plan."

After a minute or two of waiting, the office door opened again. Someone called an incomprehensible phrase, and it closed again.

"Our leader wishes you brought to him," Gerson interpreted. He opened the car door on his side, slid down to the pier floor, turning to keep his barely visible gun trained on Doc.

The old druggist shoved along the seat, twisted toward the waiting man—let his feet down to the running-board. His hand came out of his pocket and suddenly dashed a glittering spray full into Gerson's face. Doc's other hand flailed for the snouting automatic. Its shot ploughed harmlessly into the floor, and then the gun dropped from Gerson's numbed fingers that had lifted to paw at his blistering eyes. The sharp smell of Hoffman's Drops filled the car. It was the compound of ether and alcohol from the bottle with which Doc had intended to relieve the knifed G-man's death-cough, then absently dropped into his pocket when he realized it would not help.

Yellow light abruptly fell across the floor, and someone shouted. Doc leaped into the limousine's front seat, slammed the door shut and heeled the starter pedal. Gerson was screaming his agony, and men came running toward the car. There was no responsive burr. Doc remembered that he had not turned on the ignition, reached for the dashboard.

The keys weren't there!

Something crashed against the old pharmacist's skull.

DOC was shocked awake by icy water being thrown in his face.

He was lying on the floor of a partition-walled cubicle. It

contained paint-peeling desks, a battered safe... The bullet-headed chauffeur had spilled the water bucket over him. A half-dozen men, all slight, swarthy and alien-appearing, were busily

making packages of papers. Gerson was washing his eyes with a wet

rag. A man in a grey suit and Homburg was kneeling at the open

safe, taking an oilskin-wrapped parcel from it.

"These plans will make you a major in our flying corps, Lieutenant Javra," he said. "That should pay for serving in the American flying service so long that you have so nearly forgotten your native tongue."

"Careful, Colonel Makarolin," the bullet-headed man called warningly. "This fellow has come to."

Makarolin rose. He was as sharp-faced as Gerson, but showed more competence, authority—and evil. He came over and stood looking down at Doc, his thin lips twisted in a bleak smile.

"I shouldn't worry over what he hears. He will not live long."

Gerson had an automatic in his hand. "May I have the satisfaction, sir," he said, "of administering the coup de grâce?"—He lifted his gun.

Even now, looking wide-eyed at death, Doc's thoughts were not on himself. In his soul was a deeper despair.

He thought: "I have fought for individuals, families, a neighborhood—many times won out against crooks and killers. But this time it is my country that is menaced, and I have failed. These men are foreign spies. From what their leader has said, those plans must be of crucial importance. I can't stop them from escaping with the plans!"

Colonel Makarolin's fingers were holding Gerson's gun barrel, forcing it down. "No," the spy chieftain was saying. "We have fired a shot in here already. Fortunately, it was unheard out in the street. But another might bring the police."

"Then permit me to use—this."—Gerson's left hand had flashed inside his coat, came out now with a slender and very keen stiletto. He smiled evilly.

Makarolin looked at him for a long second. "No. You forget that Karlower is the watchman on this pier, and that he is not going with us aboard the cruiser that awaits us down the bay. A body here, or even blood on the floor, will cause trouble for him. This man Turner will leave here in the small boat that takes us to the cruiser—but he will not form one of its passengers for long. A corpse leaves no embarrassing trail in water. Gag and tie him up, quickly. It is almost eleven-thirty, and we must be ready."

Turner attempted no useless resistance, as Gerson and Javra obeyed. By the time he was helplessly bound hand and foot, the others had concealed their packages about their persons.

Javra looked at his wristwatch. "Eleven-thirty," he said. "I wonder..."

He broke off as the office door opened and a sallow-countenanced individual poked his head in, said something in the spies' own language. Javra bent, lifted Doc to his shoulder as if the old druggist's frail body was virtually weightless. Makarolin spat some swift instructions, lifted his hand to the lantern whose light was confined to this room by black cloth draped over its windows.

The flame dwindled, died. There was only red wick-glow in the stygian murk, then even that was gone. Feet shuffled, hinges creaked. The spies were trampling out to the pier, going toward its river end, and Andrew Turner was being carried with them. Soon now, they would be safe aboard their country's warship with the store of America's military secrets that they had amassed.

But Doc would not be with them. He would be floating in the river, a corpse that left no trail...

The shuffling group reached the end of the pier. Doc was slung over Javra's shoulder, and he could see under the bullet-headed man's lifted arm. He heard the rub of wood against the piles, saw Makarolin, leading the procession.

Abruptly, dark forms leaped up over that stringer, black water devils...

"Reach! Reach for the roof!" a voice rang out. "This is the law!"

An oath ripped from somewhere, and an orange-red jet accompanied the bark of a shot. Gun-spray laced the darkness, and gun-thunder rolled under the roof of the pier.

THERE was no longer any firing. There were only men moaning on

the pier floor or erect with their hands in the air. Dark forms

moved among them with flashlights, stopping to take from the

spies the oilskin-wrapped packets of papers.

"Oh," a voice cried. "Oh, Mister Turner!" Abe Ginsburg came into the radiance of the beam, thudded to his knees.

Abe's trembling hands slashed the lashings from Doc. "Ai,—" he chattered. "When you gave me the medicine and said I should take it to someone I know there ain't, I know that you tell me the Yiddish word Achtung—look out—and that something is wrong. I go out and watch, and pretty soon you come out with that man, and he puts you in the car. There ain't; no cop around nor nobody, so I scrooge up behind the spare tire in the back, and go with you.

"That spare tire is fancy with a cover, so those ginks outside don't see me when the limousine drives in here. I dropped off as soon the car stopped and hid in the dark.

"Pretty soon you started fighting, and I thought maybe I could help, but it was over so quick I didn't get the chance. But the ginks outside, they heard you shoot and they came in to see what was going on. I slipped out through where they left the big door a little open. Then I ran, looking for a cop or a place to telephone or something. And all of a sudden there was a car coming along, and I hailed it. Thanks God, it was full with G-men."

"The kid tells us the story," continued the man with whose knife Abe was just slicing loose Doc's last bond, "and we know our plans have gone haywire. You see, Gates, our undercover man on this job, tipped us off yesterday that this gang of spies was to meet for their final getaway at twelve-thirty, and we were all set to round them up then. Luckily our speedboat was already cached at a pier a half-mile upriver from here, so we made it down here just in time. But I can't understand how Gates slipped up by a full hour."

"He didn't," Doc said, sitting up. "They changed their plans and he tried to get word to you." Soberly, he told what had happened. "Gates got to me on sheer nerve," he finished, "but I can't understand why he made for my place."

"You're known to us, Mister Turner," Reynolds replied. "And he knew that he could give you the message for us without the slightest fear of its reaching the police."

"But why not the police?" said Doc.

"That's why not." Reynolds pointed to the pier end.

Doc turned and saw that the captured spies, carrying their wounded, were going down the ladder under the watchful guard of the Federals.

"They were working for a country with which we are supposed to be friendly," the G-man explained. "In the present disturbed state of world politics, any publicity given to their arrest might have dangerous repercussions. Even at the cost of letting them escape with what they have learned, we could not permit any publicity. There are always newspaper reporters at headquarters—frequently one in the precinct stations—and almost inevitably the news would have leaked out, if the cops handled it. As it is, we have recovered the plans, and will simply send these men down the bay to the cruiser that's waiting for them."

"How about your man Gates?"

"He will be buried in Potter's Field, in an unmarked grave," was the answer. "We can't even afford to claim him, much less recognize him as a hero. There are more such sacrifices than you think, Mr. Turner, in this country of ours, and there will be many others. Which brings me to this. You have performed a great service to your country tonight, but you must perform a greater by never telling the story to anyone. You too, young man."

"Ai," Abe exclaimed. "For sure. It is absolutely a secret by me."

"Sure you can keep it, Abie?"

"Can I keep it? Look at how I kept it a secret about the party... Ai!" the youngster broke off. "I almost forgot! Listen, mister. What time is it?"

"Ten to twelve," said the G-man.

"Ai, Mister Turner. You got to come right away quick to the Crescent Casino. Don't ask me why—just come."

"TWELVE o'clock," Jack whispered to Ann. "We can't keep these

people here any longer.—" They were in the vestibule of the

Casino, and now there was no gaiety in their faces, only

desperate worry, agonized dread. "There's no hope..." He cut it

off as the outer door swung open. Then, "Doc!—" he

shouted.

"Abe! Where have you two been?"

"I can't tell you," the kinky-haired boy said. "It's a secret."

"Abe's full of secrets tonight," a very much bedraggled Doc Turner gasped. "He's rushed me here as if our lives depended on it, but he refuses to tell me anything about it. What's the big idea, Jack?"

"You'll see in a minute," said Ann, laughing. "Just come along inside." She had the old man by one arm, and Jack had him by the other.

Then they were inside, and a great roar greeted them, and Doc was white-faced, staring at the waving, cheerful crowd, at the banners and decorations, the huge white cake on the raised table with its fifty flickering flames.

"All right, everybody," Ann's high, clear voice rang above din. "Everybody sing!"

And they sang a vast outpouring of gratitude and devotion. In Italian accents and Chinese, in Hebraic intonations and Irish, in Russian and Negroid elisions—they poured out their thanks to the trembling old man:

"For he's our own Doctor Turner,

Our white-haired, young Doctor Turner,

Our lion-hearted druggist, Doc Turner,

Ours for fifty years more..."

As he listened to that paean of appreciation, there were tears

in Andrew Turner's eyes.

"It's been worthwhile," he whispered. "Oh, how well worthwhile it has all been!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.