RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

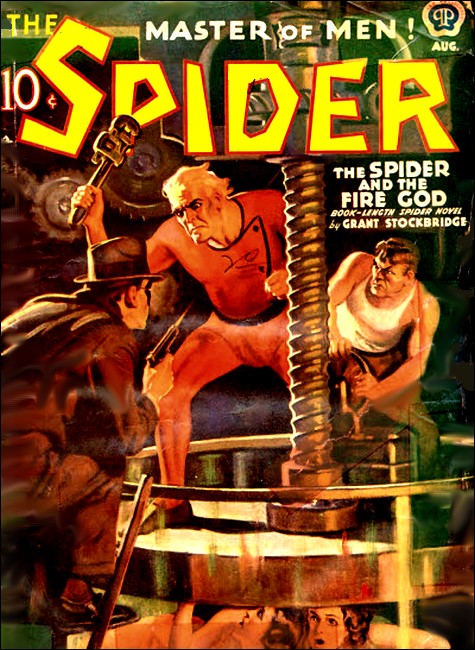

The Spider, August 1939, with "Doc Turner and the Eye of Death"

It was no more than a little disk of purple light—yet it brought terror and death to the tenements. Only Doc Turner knew how to combat that strange weapon of murder—and he was already doomed to die!

"LOOK!" someone shouted above the pushcart-market tumult. "Look at that light!" An arm rose above the lifting heads of the shuffling slum denizens. Andrew Turner looked in the direction its hand pointed.

Pole-hung electric bulbs poured garish glare down on the vivid-colored fruits and vegetables that piled the carts, but the "El" trestle which roofed Morris Street was dark with shadow. In that shadow, along rivet-studded steel, there now danced a bright purple disk the size of a silver dollar.

Apparently endowed with some eerie life of its own, the violet will-'o-the-wisp came to an iron pillar, darted down, flicked along the pushcarts, paler now but still plainly visible. It danced over pyramided oranges, over a green bank of cabbage-heads. It leaped the skull-capped, bewhiskered head of a purveyor of prayer shawls, alighted on a piebald array of dark red rhubarb, yellow celery, crimson tomatoes—then flame fountained! A huge, blinding violet flame, black-spotted with flying debris!

Thunder blasted, pounded Turner against the window-frame of his drugstore!

Screams, shrill with terror, pierced the white-haired old pharmacist's blast-engendered deafness. The dazzle cleared from his eyes and he saw shawled housewives, ragged urchins, swarthy-countenanced men, held rigid between the panicky urge to run and a compelling horror that drew them toward a smoking ruin in the gutter. For now a twisted and shapeless form lay on the sidewalk near the curb.

Andrew Turner's fleshless, acid-stained fingers shoved him away from his storefront. His shabby alpaca coat was dragged tight about his scrawny frame as he pushed through the crowd. The lines of age were cut more deeply into his gaunt, bony face. His lips were tight and grim beneath his bushy mustache.

Caught in a pocket of bodies, the druggist thrust unavailingly against a broad, overalled back. A work-gnarled hand reached over his shoulder and nudged the burly form blocking him. "Get outta the way," a hoarse voice grunted. "Let Doc Turner through."

"Doc Turner!" the fellow grunted. He shoved aside and a blonde-haired, round-faced woman exclaimed, "Ach! Here is Doc Turner." Murmurs followed the old druggist as a path for him opened magically, and the crowd's tension perceptibly eased.

These were Doc Turner's people, these poverty-stricken outlanders of Morris Street. He was their wise man, friend, protector. Nothing was quite as bad when Doc was there to take care of it. Nothing was ever so bad that Doc couldn't set it right.

He was clear of the crowd—going down on his knees beside the crumpled mass of rags, gore and charred flesh that sprawled half-on, half-off the sidewalk. His fingers somehow found a wrist in that chaos—found a pulse, as his skilled glance probed the prostrate form and made swift diagnosis. A tiny muscle twitched in Doc's seamed cheek, and his eyes went bleak, hopeless. His hands moved, slid under a thatch of hair that had been black and kinky moments ago, that now was blood-matted.

"All right, Misha," Doc Turner murmured. "You'll be all right," he lied.

Blue-painted eyelids fluttered, opened to reveal deep, dark wells of agony. "Oi," came from thick lips that were bluish in a face through whose swart stubble showed a waxen, graying pallor. "I'm hurt, Doc. Keep it from hurting..."

"In a minute, Misha. I'll give you a needle and you'll feel better. But first you must tell me what was in your pushcart that exploded."

Misha winced. "Nothing. Believe me—nothing except rhubarb and celery I put in my wagon... and tomatoes. Like always."

"But there must have been something else," Doc insisted, gently. "Somebody must have put something else in your cart. Think, Misha."

"Put..." The man's lids were closing again, his utterance the merest shadow of a voice. Doc lowered his head to hear, "Ai! Maybe... the man... with the crooked thumb. He..." Scarlet spume frothed on Misha Orlinsky's lips, and a scream was coming from them. "The light! The purple light...!" The smashed body arched, slumped down on the stained sidewalk, was still—dreadfully still.

"The light!" In a half-dozen different tongues the word rose around where Doc was crouched over a torn corpse. "The death-light," they whispered. "The purple death-light." A police siren wailed, coming fast. The distant gong of an ambulance sounded.

Doc Turner lifted slowly erect, his eyes narrowed and speculative. "Who said that first?" he demanded of the faces that walled him in. "'The purple death-light.' Who was the first one to say that?"

The faces stared at him, big-eyed, wondering, but none answered.

THE night after Misha Orlinsky died in a spurting of flame,

Morris Street was raucous again with the shouts of hucksters, was

teeming again with its shuffling sidewalk throngs. Shawled

housewives argued as they had before the purple light danced on

the shadowed trestle of the "El." Rumbling trucks bore down on

the play of ragged urchins. The youngsters screamed in hair-breadth

escapes and then sprang to hitch a ride on the very

monsters that had come within an inch of crushing out their

lives.

Life is not so precious on Morris Street that the end of one should make more than a minute's disturbance among those left behind.

There was still some talk among the people out there, about last night's occurrence, because the blast that had brought it about had not been explained—because the dancing, purple light had been a fey, queer thing. But the talk frothed as lightly on the surfaces of the slum's teeming life-stream as a bit of foam on the breast of some dark, deep river.

In the dim-lit quiet of his ancient pharmacy, Doc Turner's brow furrowed. The old druggist's fingers drummed thoughtfully on the edge of the sales counter that right-angled the white-painted showcases, and his shaggy-eaved eyes brooded. "Just a few bits of wire, Jack, and some broken glass. That was all the cops could find in the mess of Orlinsky's cart."

Jack Ransom, lounging against the outer side of the counter, thrust a big hand through his carrot-hued mop. "And they might have been in the gutter long before the accident." He was not much taller than Doc, but there was power in his barrel-chested, burly body, youth in his freckle-dusted, broadly sculptured countenance. "What makes you think the blast was anything but an accident?"

"The light, son," Doc murmured. "The little, dancing purple light."

"Hell," Ransom said, grinning. "That was probably a reflection from some light on a passing truck. Some of those big long-distance vans that pass here are tricked up like circus wagons. It didn't have anything to do with what happened to Misha."

"It had everything to do with Orlinsky's death," the old man said flatly. "It was the whole reason for it."

"Huh?" Jack's grin vanished, and his gray eyes sobered. He'd fought too often at Andrew Turner's side against the crooks who prey on the helpless poor to dismiss this assertion as senile maundering. "What have you got to back that up?"

"Three things, my boy," Doc said. "The first is the yell that directed everybody's attention to it. It was a man's voice, not a child's. Is it reasonable that any man should be so astonished by a little light like that as to shout aloud and point?"

"Well..."

"And then there was the way it was given that gruesome name, 'the purple death-light.' Somebody whispered that in the crowd, purposely, and it caught on, as he wanted it to."

"That's pretty far-fetched," the youth protested. "Your third argument will have to be more convincing."

"It is." The left corner of Doc's mouth twitched. "Misha tried to tell me something about a man with a crooked thumb, Jack! The hand of the man who pointed at the light, shouting about it—had a thumb that was curiously bent inward, held rigidly that way by a web of stretched skin."

"That does tie up," Ransom admitted. "I get your idea. You think what happened yesterday was just a plant to build up the purple light as a warning of danger or death. The yell made everyone watch it. It made sure that everyone would see Orlinsky's cart go up the instant the light touched it. And then the same fellow gave it that ominous name."

"Exactly," Doc said.

"But that seems sort of useless, doesn't it?"

"Yes. Unless—" Doc's faded-blue eyes lifted to Jack's, held them "—it is followed up. Unless, my son, the purple light appears again."

"You mean..."

"I mean that a threat of death hangs over those people out there." Doc's hand lifted, pointed out through the open store-door. "I mean that the purple light will take another victim tonight. But who it will take, or how, is something we cannot know."

"Good Lord, Doc. We've got..." Ransom broke off, his eyes suddenly widening.

A curious sound under-ran the familiar sounds that had been coming into the store—a low, growling murmur that swelled, as the youth turned and started toward the front of the store. That sound rose as the peddlers' raucous shouts died down, as the polyglot chatter faded, till it was the only sound in the fear-filled slum night.

Doc Turner was beside Jack as he reached the store doorway. The two halted on the sidewalk just outside, stared down the street to where, midway of the block, that odd noise seemed loudest.

THERE was no movement on the thronged sidewalk. There was only

a mob of shawled women, overalled men, ragged urchins, rigid as

though frozen by some mass-paralysis—every head twisted in

one direction, every pallid face uplifted to where a spot of

purple light shone on the rain-stained brick of a tenement's drab

facade.

"The light," Ransom husked. "The purple death-light."

As if his ejaculation were a signal, the luminous disk vanished from the wall and reappeared at once on the up-flung arm of a full-bearded, long-cloaked Hebrew patriarch. The man burst into flame, into a whirling, vertical maelstrom of violet fire out of which came a high, animal-like scream of anguish.

"God!" Jack Ransom groaned. "Oh, God!" Pandemonium burst from a hundred horrified throats.

"Look!"

The pillar of violet fire that swirled about a screaming man toppled. A purple spark flew from it. Not a spark—the light-disk of death! It was on the tenement wall again. It ran along that wall, between black, gaping rows of windows. It found a wider space where two buildings joined, and it hovered there—and all of terror-stricken Morris Street knew that it was choosing its next victim.

A screaming, panic-stricken mob surged away from that hovering menace. From the corner, too far away to see what was happening, another mob surged toward the center of the disturbance, morbidly curious. The two surges met, jammed...

"Look out!" voices screamed. "It'll get you." A tall gaunt man, black-garbed, was somehow alone in the vacant space the crowd had cleared. "Look out!" As if hypnotized by his fear, he stared straight up at the dreadful death-light on the wall. The purple disk was leaping straight for the doomed man.

His hands flung up, cupped, met it as hands meet a thrown ball! It was a ball—a brilliant amethyst ball held high in those daring hands. A sudden silence hushed the cries of the crowd, a silence that awaited new horror. But no purple fire flamed about that tall, gaunt man. No death-blast blew him to bits.

"The death of Ishtar," he boomed, holding the blazing violet sphere high above his head. "It strikes not the chosen of Ishtar!" He was completely bald, and his skin, weird in the amethyst light streaming from the disk, was tight-drawn over the bones of his head. His eyes were deep-socketed, his cheeks sunken, his lips shriveled away from withered gums. "Bow to Ishtar, lest her purple death find you!"

"I get it!" Jack exclaimed. "You were right, Doc. What happened yesterday was..." He broke off. Turner wasn't there beside him. The old man had vanished...

"I am Amen-Hotep," the skull-headed man boomed. "High Priest of Ishtar. A thousand, thousand years I have served the Purple Goddess. Tonight I can save you from Ishtar's death-light." His hands made some obscure movement, and the purple brilliance was gone. "Tomorrow not I, nor any earthly power, can save those who refuse homage to Ishtar, Goddess of Death, Goddess of Everlasting Life."

"Damn!" Jack grunted, and was shoving through the silent, listening crowd. So tensed were they that his thrusting shoulder seemed to be battering dummies out of his way, not humans.

"Tonight you must make your choice," Amen-Hotep cried. "You must choose between immortality in the bosom of Ishtar and Ishtar's purple death. Tonight—"

"Bunk!" Jack burst out of the crowd, grabbed the fellow's shoulder, turned to the packed mob. "He's a faker, folks." He turned back to Amen-Hotep. "You're under arrest," he panted. "As a citizen witnessing a crime, I have the right to arrest you, and I do."

"Yes?" Amen-Hotep demanded, strangely unperturbed, his fleshless lips drawing away from pointed teeth in a skeletal grin. "What crime of mine have you witnessed?"

"Murder," the youth grunted.

"Whose murder, pray? Where is my victim?"

"That old man. You set him afire and..." Jack, turning to point to the charred corpse of the patriarch, broke off, gasping. It wasn't there. On the cracked sidewalk where he'd seen it fall was nothing at all...

AMEN-HOTEP laughed—if the weird, intonationless sound

that came from his withered lips could be called a laugh. Then

his voice was raised again so that all could hear. "Your lack of

faith might have cost you dearly, had I not been merciful.

I, who have saved hundreds from Ishtar's death, you

accuse of murder! But I have taken compassion on your ignorance.

I call upon Ishtar to spare the assailant of her high

priest."

Ransom's fingers dropped numbly from the fellow's shoulder. He was cold, shivering, though the night was warm. Was Doc wrong? Was what was happening here truly a manifestation of some supernatural force?

"Only for tonight," that great, booming voice went on, "have I the power to save you or the others from Ishtar's dread death-light. From the coming of the morrow's dawn, those who have not embraced Ishtar's faith must brave her vengeance."

Doc Turner had moved to the side of the carrot-headed youth. "That was a clever trick, Mr. Amen-Hotep, dressing your accomplice in asbestos and masking his face with an asbestos beard, to protect him from the flames." He spoke low, so that only Jack and the gaunt, skull-headed man could hear him. "And then holding everyone's attention while he beat out the fire and sneaked away. But you won't get away with it, my friend." His hand, on Jack's arm, gently started the lad away. "Come, Jack. We can't do anything just now, but we'll spike his little scheme."

"I'll say, we will." Ransom laughed, but his laugh was without conviction.

"Those who would find safety in Ishtar's bosom from her vengeance," the skull-headed man's booming voice went on, "will come to her Temple of Life and Death in the hour before dawn."

"Where is it?" a fear-thinned voice yelled. "Where's Ishtar's temple?"

"The light will lead you," was the answer. "Ishtar's purple light of death and of everlasting life. Disperse now to your homes to meditate upon your sins, but be in the streets at the hour before dawn to follow Ishtar's light to Ishtar's bosom!"

JACK and Doc reached the door of the drugstore. Behind them

the awed throng was breaking up in a bated murmur of voices and a

dragging of slow feet that told of the fear that sapped strength

from weary limbs.

"How did you guess that guy with the beard was working with him?" Ransom asked the old druggist.

"I didn't guess." Doc closed the store door. "I knew. When he threw his hand up I saw that his thumb was crooked. I watched him, instead of Amen-Hotep as everyone else did, and I saw him beat out the fire. His suit must have been saturated with some inflammable liquid in which potassium or rubidium salts were dissolved to give the flame that purple color."

Doc went on. "He rolled off the sidewalk and under a pushcart after the fire was out. I tried to get around there, but I couldn't get through the crowd fast enough. Then I heard you playing right into Amen-Hotep's hands by giving him a chance to call the mob's attention to the dramatic disappearance of the supposed victim of Ishtar, and I got through to you."

"Why didn't you expose him?"

"Because..." Doc smiled bleakly. "If I'd tried it, I would have forced him to kill me in some sensational manner, and thus simply reinforce the ascendancy he's gained over his dupes. That man is as shrewd as he is dangerous, Jack—too shrewd for us not to be prepared to deal with exactly that situation, if it arose. His whole plan would be smashed if some child, say, had observed his accomplice's actions and cried out."

"I get you." Small muscles knotted along Ransom's blunt jaw, and his eyes were sultry. "Ishtar would have killed again in some spectacular fashion, and there would have been no trick about it."

"Exactly," Doc said. "Not knowing how it would be done, I could have no defense against it."

"But you did tell him that you were on to him," Ransom insisted. "Why that?"

"It let him know that he was not deceiving me, and warned him that I would oppose him," Doc said. "He had the crowd going. He should have taken them right off to whatever devil's rites he's planning to pull off at his so-called temple, without giving them time to recover from his demonstration. Can you doubt that he planned to do this? Why then, do you think, did he send them to their homes, order them to wait till the night is almost over?"

Jack's lids narrowed. "Because he's afraid you'll throw a monkey-wrench in his scheme. Because he's afraid of you."

Doc nodded. "And intends to get rid of me before I get another chance to upset his apple-cart. Do you understand now?"

"Yeah," the carrot-head grunted. "I understand. You've made sure he'll come after you."

"Very soon, I hope," the old druggist said grimly. "Which is why I want you to get out of here, my boy."

The pharmacist's hand went sideways, as if gesturing. It struck a box of cleaning tissues on the showcase beside which the two were standing, knocking it to the floor.

"Pick that up, Jack," Doc directed, "and contrive to look across the street as you do so."

Ransom bent to obey. Peering through the plate-glass store door, he saw a thoroughfare strangely deserted for this hour. His gaze went across the cobbled gutter.

Within a shadow-filled tenement vestibule opposite, a form lurked, shapeless and black except for the paler oval of a face.

Jack put the tissue box back on top of the showcase. His mouth was a hard, thin line in his freckled countenance, and two white spots showed either side of his flaring nostrils. "Someone's watching us, huh?" he grunted. "I'll soon fix that."

"No," said Turner, smiling. "You'll pay no attention to him. You'll just say goodnight to me and walk out of here, and you'll go straight home..."

IT was quiet, too quiet, in the badly-lighted drugstore on

Morris Street. Although a partition and the full length of the

store intervened between Doc Turner—filtering some lime

water in his prescription room at its rear—and the clock on

the sidewall of the display window, every tick of the latter's

pendulum was like the stroke of a hammer.

Frail, acid-stained fingers adjusted the rubber tube that was siphoning milky liquid from one five-gallon bottle into the funnel that rested in the neck of another. Very deft were those fingers, very steady. There was not the least hint of fumbling about them, not the least quiver to show that the white-haired old man was waiting for the imminent approach of a killer for whom he had made himself bait.

Abruptly those fingers stopped moving. Doc's head turned, ever so slightly, in the direction of the arched doorway from the front of the store. The faded curtain that filled the aperture did not reach quite to the floor. In through the space beneath it a disk of light was slowly creeping—a disk of purple light the size of a silver dollar. Andrew Turner's right hand dropped into a drawer that was half-open in the front of his scrubbed-white compounding counter.

The amethyst death-light came slowly along the bare boards, toward him. Doc's hand came out of the drawer, and there was a gun in it, a gleaming automatic.

The violet light reached Doc's toes.

The gun dropped from the old man's hand, and he slid down along the front of the compounding counter. He lay crumpled on the floor and did not stir...

THE stars were paling in the sky over Morris Street and the

tenement-lined blocks that ran into it. A grayness stole across

the sky, the grayness of the false dawn. The streetlights went

out. From the river came the melancholy hoot of some nocturnal

tugboat.

Here and there in the drab, weather-stained fronts of the rabbit-warrens where dwell the very poor, a vestibule door opened. Here and there a darkness-shrouded figure stole down a broken-stepped stoop, stood irresolute on a cracked and débris-strewn sidewalk.

A strange waking had come into the streets of the slum. A waking of fear-chilled men and women who stood waiting for a sign... who stood waiting for a purple light.

"There it is!" someone cried in Hogbund Lane, and someone else shushed the brazen voice to silence. High up on the mouldering brick of a dilapidated tenement, the purple disk started moving in the direction of the river. In the street below, the gloom-cloaked figures started to follow it. The shuffle of feet moved toward the river in Hogbund Lane, from all the streets of the slum that is arteried by Morris Street. The shuffle of moving feet converged on a blind-windowed black-façaded warehouse that faced the river—a warehouse that had long been deserted.

The great doors of the warehouse swung open, and the people of Morris Street followed the death-light of Ishtar into a vast, resounding vault that was pitch-black as the foyer of Hades...

PAIN swelled Doc Turner's head. It ballooned till it was as

big as the world. Pain ripped it. It collapsed to the size of a

grain of wheat and started to swell again.

The old man groaned. He tried to lift an arm to his aching head, but his arm would not move. His arms, his legs would not move.

A faint violet luminance flowered in the blackness to Doc Turner's right. Another to his left. The violet deepened. The vague spots of radiance became purple flames dancing in two bowls that were supported on ornate tripods.

The bowls and tripods were of some lucent crystal, so that the amethyst light filled their entire substance and they became radiant braziers of purple light. The purple light spread about them, filling the space within which Doc lay, reaching up into a blackness-roofed space above him, reaching out into space that stretched away from him.

That space was crowded with half-seen forms, with faces eerily painted with violet light, eyes wide-pupiled and staring. Not even the pungent tang of incense could cover the smells that came to Doc's nostrils from that close-packed throng—the smells of alien foods, of bodies toil-bathed with drying perspiration... the telltale odor of poverty. Had the old druggist not already known it, that odor would have told him that these were the people of Morris Street out there, his people.

The purple light deepened.

He was lying on a sort of raised bier, elevated in turn by a platform that supported also the lucent braziers to his left and right.

Only by twisting his head agonizingly could Doc see what was behind him, ten feet away. There, the wavering purple luminance of the braziers spreading over it, towered the colossal image of a woman. High above him it loomed, and it was of wood once ornately painted in vivid colors, in greens and yellows and gilt. Those colors were faded now, the wood raddled by cracks. But the gigantic face of the woman was lifelike, as if it were of living flesh—the long-lashed, grim face of a woman who had seen too much of evil.

The arms of the woman were overstretched above Doc. The hand of the left arm held a cradle on its upturned palm. On the palm of the right lay a coffin.

This was the image of Ishtar, Goddess of Death and of Life, and Doc Turner lay on an altar before her.

Looking down at himself, he saw that his arms and his legs were fastened in such a way that, though he could not move them, to the people below the platform he would seem free to move; appear to be lying on that altar of his own free will. Oddly enough, his clothing was sprinkled with a grayish powder, and on his chest was fastened a queer little square, black box.

Amen-Hotep drifted to the altar on which Doc lay.

"Welcome," his great voice boomed. "Welcome, neophytes, to the Temple of Ishtar. Welcome to the abode of death and everlasting life."

A rustle answered—a wordless rustle from the purple-lit darkness to which he spoke.

"Too long has the worship of Ishtar been forgotten on this earth," he began again. "Too long has her wrath smouldered unsated. Now it is heated full flame against those who have denied her, now it is poised to strike. Only in her bosom is there safety from her vengeance, only in obeisance to her, safety. Is there any here who is not ready to swear obedience to Ishtar? Any who would deny her?"

"Yes!" The shout came from Doc Turner, lying helpless on the altar. "I deny your Ishtar. I say she is a fake and you are a fraud. You are a fraud and a murderer, and all this is only a scheme to milk these poor people of their last hard-earned cents."

"Doc Turner!" someone cried, out there. "It's Doc Turner, folks!"

"It's Doc Turner," the pharmacist shouted. "You've known me for years. You love me and believe in me. Listen to me now. I tell you this is a fake and a fraud. His death-light is only the beam from a flashlight with a colored lens. His Ishtar is only a wooden statue, falling to pieces. It can't harm you. It can't—"

"Silence," Amen-Hotep thundered. "Silence, scoffer! Silence, blasphemer!" Then he turned to the muttering crowd. "Silence, you of little faith, while you watch how Ishtar deals with those who blaspheme her. Silence! The death-light of Ishtar appears."

His robed arm lifted, pointing straight upward. Far above Doc, on a raftered ceiling, the purple disk blossomed, hung.

"Ishtar strikes!"

THE death-light dropped straight down upon the recumbent old

man who, helpless, had defied his captor! Straight down, but in

the split-second before it reached Doc, a brilliantly red light-shaft

leaped from somewhere in the crowd, struck the old man,

shone scarlet on the little black box that was fastened to his

chest. The purple light reached that box...

Nothing happened.

"That's how much your Ishtar's wrath amounts to," Doc flung at the staring, astounded man in purple robes. "That proves that she is a fake and you a fraud."

The sound of pulled-in breaths was like the sough of a great wind in that rafter-vaulted hall. "Faker!" a shrill voice screamed. "Murderer!" Feet shuffled, and a sea of black forms surged toward the platform.

"Damn you!" Amen-Hotep spat and leaped at Doc, a knife in his hand, flashing purple. The knife sliced down...

A fist battered it aside, swung again and landed on the point of the killer's jaw. It was Jack Ransom's left fist that had pounded the snarling face of Amen-Hotep. His right hand clutched a flashlight from which crimson light streamed. He kept that light on Doc, on the little box strapped to Doc's chest.

The priest straightened and leaped in again at Jack, his knife flailing for the carrot-headed youth's throat.

Ransom's left arm, flung across, took the blade in its biceps. Pain informed Jack's outcry, but still he stood straddle-legged, still he held that red light on his white-haired friend. Amen-Hotep tugged his weapon free, lunged in again.

He was caught by work-gnarled, dirt-grained hands, dragged backward, went down under a swaying mass. There was the thud of heels on flesh, a babbling scream...

Jack Ransom swayed, white-faced, blood blackening his sleeve, dying his left hand scarlet, but still he kept that crimson beam on Doc. His teeth dug into his lower lip. He got moving, staggered against the edge of the altar and fell over Turner—over the little black box that was strapped to Turner's chest.

"Okay, Jack," Doc said. "That does it. I'm safe now."

The flashlight dropped from stiffening fingers and rolled away. But yellow light came on in a dingy high-ceilinged hall, and a crowd of muttering slum-dwellers drew back from the still heap of robes that lay on the floor, not purple now, and in the eyes of the crowd was a sort of horror at that which they had done.

"Come and take care of Jack," Doc called. "And then cut me loose."

A CHILLY morning light came into the old drugstore on Morris

Street, brightened the white-painted shelves, bathed with pale

sun the figures of a white-haired, tired old man and a carrot-headed

youth whose left arm was swollen twice its size with the

bandages wrapped around it.

"I did what you told me," Jack Ransom was saying. "Put that red light on you and kept it there in spite of hell."

Doc smiled bleakly. "If you hadn't done that, I would have been bathed in flames the instant the purple light-disk hit me, and I didn't have any asbestos suit on to keep them from scorching me. That little black box strapped to my chest contained a photoelectric cell so adjusted that when a bright purple light shone on its lens, it would spark and ignite the explosive powder with which I'd been liberally sprinkled. That's how the bomb hidden in Misha Orlinsky's pushcart was exploded, and how the man with the crooked thumb was set afire last night. The purple light was a death-light, all right."

"But why the red flash?"

"Red is at the other end of the spectrum from violet. The red light canceled out the effect of the violet one, and so the photoelectric cell didn't act. But if it had swayed from me for one instant while the violet was on me..." Doc shuddered.

"You didn't have to chance it," Jack said. "You could have stopped Amen-Hotep some other way."

"Not without killing him, and even then his crook-thumbed accomplice would probably have taken up where he left off," Doc said. "I had to convince my people, spectacularly, that they were duped, and the only way to do that was to outguess the fellow who was working on them. I had a bad moment, in the store, when that gas started hissing in and I thought, 'What if I'm wrong? What if he isn't going to use me to remove the last shreds of doubt from the minds of his victims but is going to kill me now?'"

Jack's mouth twisted. "You know, Doc," he mused, grinning, "sometimes I think you like to go at these things the hard way—as if you were playing a game that isn't any fun unless the rules make it difficult."

Doc Turner's faded blue eyes wandered past him to the open door, out to where overalled, swarthy-countenanced men were going past on their way to work, and shabbily dressed urchins on their way to school—out to where pushcarts were rumbling into place along the curb and a few shawled housewives were gathering for their early marketing.

"Maybe," he whispered. "Maybe it is a game, Jack. But if it is, the prize is well worth while."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.