RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

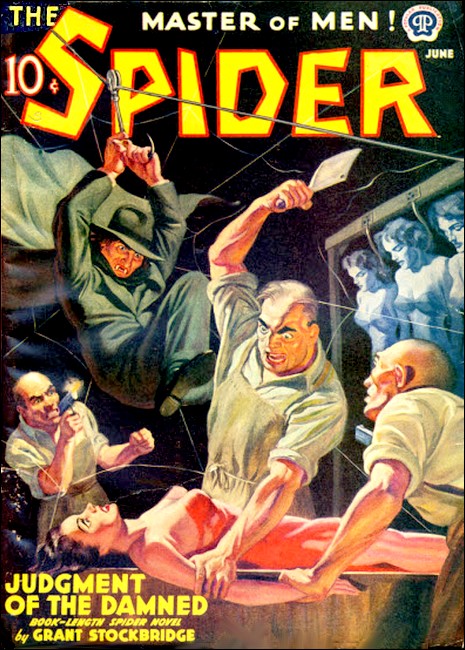

The Spider, June 1940, with "Hell, Incorporated"

Old Doc Turner and his young friend, Jack Ransom, praised Allan Forbes for sending thousands of slum boys to summer camps—until the astute, elderly druggist read little Izzy's cryptic letter—and deciphered a message of unutterable doom!

ALL day, Morris Street's littered gutter and cracked sidewalks had shimmered in the sun's midsummer blaze. No relief had come with darkness; only a breathless and more dreadful heat.

Shirt-sleeved, and with their collars open at the throat, Andrew Turner and Jack Ransom sat on rickety chairs in front of Doc Turner's ancient drugstore. The little pharmacist seemed frail, stooped by the burden of his long years. His silken mane and bushy mustache were white as his immaculate linen; his great hawk's nose was webbed by threadlike red capillaries. Ransom, burly beside him, was one-third the other's age. Boyish freckles still dusted Jack's, blunt-jawed countenance. His carrot-hued mop of hair was tousled and unkempt. His grey eyes were crinkled with young laughter.

A strangely assorted pair to sit thus in wordless intimacy, but the course of their comradeship was stranger still. For Doc Turner was more than druggist to the aliens who swarmed Morris Street and its purlieus. He was their champion against the human wolves who prey on the helpless poor. In Doc's forays against those meanest of crooks, Jack Ransom, garage mechanic, was the good right fist that made effective the subtler finesse of Doc's brain.

They had been talking idly of certain stirring experiences in the past, but now it had grown too hot to talk. Or, perhaps, some not quite realized premonition of a new adventure held them silent.

Certainly there was no intimation in the thronged scene before them of what the night was to bring. Red-eyed hucksters sought to protect their greens, but lettuce and cabbages withered swiftly despite the use of watering cans. Slow-moving on the sidewalks, lax-bodied women, toil-worn men, had fled their cheerless flats to the furnace in search of a breeze that did not exist. Over all, hung odors of the slums and poverty.

Overhead, rumbled a train on the brooding black trestle of the "El." Yellow rectangles of light skimmed the crowd's heads. The train's thunder dwindled and the hoarse cries of the peddlers could be heard again, the racket of late trucks on the cobbles between the curbs; the shuff-shuff of broken shoes on pavement. Thin but insistent, another sound underlay all these, the fretful whining of a thousand sleepless, heat-tortured babes.

Doc Turner stirred. "Queer," he murmured, "what a difference their not being here makes."

"The kids?" Jack nodded. He too had noticed the absence of one accustomed strain in the symphony of the slum's dreadful summer night. "Yeah. This same time last year you'd hear them screaming as they ducked out from under the trucks, yelling in the gush from fire hydrants turned on when the cops wasn't looking, razzing the peddlers while they swiped bananas from the carts, and all of them hollow-eyed, sick with the heat. Tonight they're up there in God's green mountains. In my book, this here Allen Forbes rates a diamond halo."

"Buddies, Incorporated," Doc mused. "Remember how every newspaper hammered at it all spring, every radio commentator, every minister and priest and rabbi?"

"And how! You couldn't get away from the slogans. 'Invest in Democracy,' was stretched on banners across every downtown street. 'Two in one for better citizenship,' flying from every hotel and department store, and on every movie screen; 'A buddy for every child today, a friend for every man tomorrow!' What a wow of a campaign, and did it go over!"

"It certainly did, Jack. I understand that there are nearly ten thousand children in the Buddies' Camps, stretched all across the northern part of the State."

"Sure there is. Forbes' idea was a natural. Here's all that mess across the ocean brought on by a couple smart guys who've made themselves big shots by playing the poor against the rich, the rich against the poor, and sneaking in between. Here's a few wise eggs on this side trying the same game. Agitators yelling to the poor how the rich have got horns and hoofs; sly birds whispering to the rich how the poor are going to revolt, any day now. And here comes along a guy that says, 'Look. In America there ain't no real difference between rich and poor. We're all just humans trying to get along the best way we can, and deep down in our hearts we know the way we can get along best is by everybody helping everybody else, because there's enough for all of us in this great country of ours. But we don't know that's the way the other fellows think too, on account of the way the big-mouth agitators and the sly birds have got us fooled.

"'All right' this Allan Forbes goes on, 'The way to queer their game is for every one to get to know each other. That's pretty hard for the grown-ups to do, because their ideas are set. But kids' ideas aren't set yet, and they're tomorrow's adults.'"

"Yes, son," Doc tried to interrupt. "I've heard all that, over an over—"

"'So what?' everybody asks Forbes." Jack's enthusiastic word-flood was not to be damned. "'So you're right, but what can we do about it?'..." And Jack went on, blithely extolling the merits of Allan Forbes' novel idea for promoting democracy and affording slums boys an outdoor summer at one and the same time. So he formed Buddies, Incorporated, an organization which purchased a great many financially insecure camps, and sold thousands of dollars worth of stock to philanthropists... People accustomed to sending their sons to camp paid the regular fee of three hundred dollars; but for each full-paid youngster, there was one under-privileged kid. Each pair of "buddies," one rich and the other poor, were to tent together, play together, work together—until in their young minds there would exist no difference between wealthy and poor. This, the spirit of true democracy, would endure in those boys' hearts forever more!

"By gosh!" concluded the exuberant Jack Ransom, "I'll tie my neck to a ton of iron and jump in the river if it ain't the greatest thing that's happened in America since the Declaration of Independence!"

"Almost greater," Turner ruminated, his gnarled fingers drumming on his knee, "if it works out as advertised."

"Huh!" Ransom's head jerked to a note of doubt in the old druggist's voice. "What makes you think it ain't, all of a sudden?"

"I don't know that I do." A certain bleakness spread over Doc's seamed countenance. "I'm not sure. But there are one or two things in that set-up that have me a little troubled. Forbes' rule, for instance, barring visitors from the camps."

"Hell! Poor relatives couldn't make the trip, and if rich ones were allowed in it would show up an awful class difference. You want any better reason?"

"No-o-o. And yet—look here, son. You know that the boys from this neighborhood went to Camp Nokomis, on Lake Heron. Many of their parents can't read English, so they've been bringing their sons' letters to me to read to them. In some of them I've felt a certain underlying—well, something that worries me. But here comes Reba Krupinsky and unless I'm greatly mistaken that letter she's carrying is from her Isidore. Listen as I read it to her. Perhaps you'll get what I'm driving at."

"Oke, Doc. I'll keep the wax out of my ears."

ISIDORE KRUPINSKY'S mother wore a black and very evident wig,

the ritual shaitel that had replaced the hair shaved off

just before her wedding in Kishinev, many years ago. The joints

of the hand that tremblingly held out to Doc a crumpled,

pencil-addressed envelope were swollen, its skin speckled with

little cuts. But her cotton house-dress was spotless, crisply

starched, and her tiny black eyes were shining.

"Oi, Doc," she quavered. "You must excuse me, I make you so much trouble—"

"No trouble at all, Mrs. Krupinsky," the old druggist said. He smiled as he took the envelope and extracted its grimy enclosure. "I'm interested to hear how Isidore is getting along."

"Nu, Doc." Reba peered at Turner, who was reading the childish, unformed scrawl, his face expressionless. "Nu? He iss all right, mine Izzy?"

"Fine." Doc looked up, and he was smiling. "He says: 'Dear Mom. I am feeling fine. Your package came last night and you ought to see my Buddy, Roger Pierson, go for the salami and the knishes. I told him that was nothing, he ought to taste your cheese blintzes. So he made me promise to bring him home for supper soon as we get back. Camp is swell. Tell Doc Turner we are all as happy as the boys in the story about Passover that grand-pop used to tell him. Doc will know what I mean. Lots of love to Pop and a great big hug for you, Mom. Your loving son, Izzy.'"

"Did you hear?" Reba's hands were lifted as though to call Heaven to witness a miracle. "Could you imachine? A son from J. Piermont Pierson, the millionaire, und mine blintzes he vants to eat!"

"I'll bet he'll enjoy your blintzes," Jack said.

"He ought to," said Doc. "I'll vouch for them. Now you run along back to your Herring Store and tomorrow morning I'll write an answer for you."

Reba Krupinsky trotted off. Jack Ransom grinned. "Well," he said, "I didn't hear anything in that letter to fuss about."

"No." Doc turned to him. The smile was gone from his face, and there was something in his eyes that wiped the grin from the youth's. "Or rather, you heard it, but could not understand. The story, Jack, that little Isidore heard old Isaac Krupinsky tell me not long before he died was the tale of the Passover of 1903, that Hebrew Easter when a mob of vodka-inflamed peasants invaded the Jewish quarter of Kishinev, burning and killing. It was the tale of a pogrom, a massacre, and the boys in it were inmates of an orphanage over whose merry Seder feast Isaac was presiding. 'We're all as happy as the boys in the story.' The boys in that story, Jack, crouched white-faced with terror as they watched the red glare of arson dance on the walls and listened to death howling outside."

"I get it!" A muscle twitched in Jack Ransom's cheek. "Izzy was telling you that—"

"That whoever is censoring the boys' letters would not understand, but I would. 'We're in terror of our lives,' he was saying, 'and they won't let us call for help!'"

Jack came up out of his chair. "We'll call the State Troopers right away—"

"And tell them what? That someone is threatening to massacre the youngsters at Camp Nokomis? That a boy from the city streets is frightened by the hooting of owls in the forest night? We've got to have something definite to tell them, or we'll simply get laughed at for our pains."

"All right." Ransom's big hands were knotted into fists at his sides. "Then I'll gas up my flivver and go up there and get something definite for the cops." He wheeled away.

"Wait!" Doc's sharp call stopped him, swung him back. "Come back here and pick me up. I'll be ready in about fifteen minutes."

"Pick you—" Jack's jaw dropped. "Cripes, Doc! Even with my hopped-up motor it's an all-night trip to Lake Heron, and God knows how long we'd be kept up there. What about your store? You haven't had it closed a whole day for fifty years."

"That's right. I haven't been out of it more than six hours at a time for fifty years." The corners of Andrew Turner's mouth quirked with grim amusement. "It's about time I took a vacation."

CLIMBING, forever climbing, the dilapidated sedan bumped up

the narrow dirt road its headlights picked out of the black

night. "Good thing you had this blanket," Doc gasped from the

back seat. "Even all wrapped up in it I'm not exactly warm."

"We're plenty high up in the mountains," Jack grunted. "Keep wrapped up tight." After a few moments of comparative quiet, Jack went on talking.

"Look, Doc! While you snoozed back there I been doing some figuring to keep me awake. The cash the Buddies, Incorporated stock brought in to buy the camps was taken care of by the Fidelis Trust Company, so I guess that's hunky-dory. But the money that's paid in for the kids is being handled by Allan Forbes' and his own hand-picked staff. The average is three hundred bucks for each pair of Buddies, and there's five thousand pairs, more or less. Three hundred times five thousand, that's—"

"A million and a half."

"Right." Ransom glanced back, wondering why Turner's voice sounded muffled, saw that the old druggist had pulled the blanket up over his ears and mouth so that only his white hair glimmered faintly. "And that's a pretty sweet sum for a crook and his mob to play around with."

"If they have run off with it, leaving the children marooned, we would have heard—"

"Cripes, they couldn't make off with the whole boodle right away. If they tried to pull it out all in one big haul the banks would catch wise. But look. Almost the whole of the camps' running expenses is for wages and food. The wages the mob gets, so that money's already part of the gravy. Now suppose they feed the kids only just enough to keep them from starving, but check out all they really ought to be spending on grub for the ten thousand boys. By the end of the summer they'll have pocketed about a million. Then they scram, and by the time the kids can get word out to civilization, they'll be out of the country. That's why they're not permitting any visitors. That's why they're reading all the campers' letters, making sure no complaints—"

Jack wrenched at the wheel, twisting the sedan into a sudden S-curve. The headlight beams shot out into the black and empty night, and he had an instant's glimpse of the banking falling away steeply from the very edge of the road. Then the whispering woods closed in again, still black, still ominous, but by contrast a little less hostile.

"It figures, don't it?" Ransom dragged his mind back from that appalling abyss, from the thought of what a moment's inattention, just then, would have meant. "It wraps up everything we know and ties it into a neat bundle."

"Too neat." Doc's blanket-muffled reply came. "Everything would have to work out too neatly for such a grandiose scheme to succeed. A single loose end, it would all unravel. You may be right, son, but suppose we wait till we take a look around the camp before we make up our minds. How much further is it to Camp Nokomis?"

"Not far, according to the map. Maybe a couple miles. Any minute now we'll be getting to the fork where this cowpath splits."

THE trail leveled, but trees closed in to hide another curve

ahead. Careful. "Might be a good spot, right there, to hide the

car while we scout—" Headlight glare, leaving the brown

trunks along which it had been sliding, found an erect figure in

the middle of the road! "Duck, Doc," Jack mumbled, looking

straight ahead. "Duck and keep mum."

He slowed, let the car coast. The man wore the thick-soled leather boots, the heavy lumber jacket and round cloth cap of the region's natives, but what a two-day stubble left visible of his face was sallow, not leathery and weather-beaten as theirs.

He was making no move to get out of the way. Jack braked, said, "Hello," getting in the first word. "How far is it to the Little Falls fork?"

"Little Falls, huh?" Except for the hoarse voice that issued from between thin, still lips, the fellow might be a carved statue standing in the brilliance beyond the flivver's bonnet. "What give you the idea you could get to Little Falls this way?"

"Why, the map shows that the cut-off over this mountain is thirty miles shorter than the highway, and I'm in a hurry, so I thought I'd take a chance on it."

"Yeah? Well maybe you'd better think again." The skin at the back of Jack's neck tightened as the hooded eyes flicked down to the sedan's license plate, flicked back to meet his own. "From down-state, ain't you?"

"So what?"

"So you wouldn't know we had a storm last week that washed the Little Falls road down into the valley. Guess you'll have to turn back, punk and take the main road."

"Turn back! Punk!" Would a mountain man know that city crook's argot? "How am I going to turn on this cow-path?" Why, for that matter, was a mountain man wandering about at four in the morning?

"You passed a wide place about a hundred yards behind. Back up to it and turn there."

"Cripes!" No use going off half-cocked; maybe this bird was legitimate. "I'm already jittery imitating a Swiss goat." Jack decided on a test that would force the fellow to show his true colors. "I'd go off the road sure. Look. According to my map, the other fork of this road goes right to some boys' camp. I'll run on and turn on their grounds." He let in his clutch and the sedan started rolling forward.

"Like hell you will." The man wasn't moving. "All right, punk. You're asking for it." His hand was slid under his mackinaw, and Jack heeled the accelerator. The sedan leaped in response. The thug sprang to the side of the road just in time, gun-metal flashing. The car went past.

The gun fire was followed by a loud bang, and the sedan was slewing, skidding. Jack Ransom fought the wheel but a huge tree hurtled at him out of the dark. Blackness smashed into his skull and a vast, rending crash followed him down, down into oblivion.

CONSCIOUSNESS seeped very slowly back to Doc Turner's brain.

He was all crumpled up on some hard, queerly canted surface in

tarry darkness, and something was smothering him. It was the

blanket with which he'd wrapped himself, in the rear of Jack's

sedan. He must be still in the rear of the sedan, on the floor

where he'd been hurled by the crash. His temple had struck the

back of the front seat, and that was the last he remembered.

"Plugged the right front tire, boss," a gruff voice said, "and the blowout smashed the car into that tree." Doc lay very still. "I slipped, dodging a wheel that broke loose, and rolled fifty feet down the hill before I could stop myself. I was climbing back when I saw your light shining up here."

"I spotted headlights travelling the road and hurried to see if you needed help." A far more cultured voice this, but tense, breathing hard. "What happened, Buck? Weren't you able to turn him back?"

"Sure. Sure I was turning him back, but he was going to the camp to do it, if he had to run me down to get by. So I let fly. The tire, right in front of me, was a quicker mark, and surer, so I took that but now I can finish Mister Nosey off. Gimme a glim a minute."

That click was a revolver being cocked. They were going to shoot Jack. A cry tightened Doc's throat, but before it could come out he heard a sharp, "No! No, Buck. Hold it."

"But looka, boss!"

"He's dead already." Fingers tightened about Doc's heart. "Even if he isn't he will be soon, from what my light showed me, and the way it is now, it looks like an accident. That's why I haven't gone any nearer than this to the wreck, so no footprints will show anyone else was near. It's fortunate that something like this didn't happen till tonight, when we're ready to make our move and clear out. As it is, we can skip through Little Falls and thence up to the border, and no one will be the wiser."

"So what do I do now?" Buck asked. "Hang around here?"

"No. There will hardly be another car starting up the mountain till daylight, and by the time the sun's an hour high we'll be through. Come with me."

"Oke." Doc heard bushes thresh as men forced through them, and vanished. He pulled in relieved breath. The dark blanket, wrapping him in the dark of the twisted tonneau had hid him from sight.

Wincing, he pulled himself to his feet. The blackness was no longer absolute. A grey half-light sifted through the leafy canopy of the forest and presently he could see the sedan's hood accordion-pleated against a giant oak, the smashed windshield, and a dark form grotesquely slumped over the steering wheel. Jack!

Dead, the voice had said. Jack, young and strong, with all his life before him, was dead. Old Doc, feeble, yearning for the last long rest, was alive. Maybe Jack wasn't quite dead yet. Maybe, with prompt first aid, he might yet be saved.

Doc Turner's trembling hand found a door handle, twisted. He was out of the car, tugging at the front door to open it and get at Jack.

It resisted him. Abruptly Doc froze. He'd recalled something else the voice had said: "By the time the sun's an hour high we'll be through." Already the sky was swiftly brightening.

For a long minute of agonized indecision Doc Turner was motionless, torn between helping the carrot-headed youth he loved, and the desperate need of those others, two hundred or more youngsters. Rich and poor. They too stood only on the threshold of life, and the lives, the hearts, of two hundred mothers like Reba Krupinsky were bound up in theirs.

It would take only a second to open this door and get fingers on Jack's pulse and determine if there was a flicker of heartbeat. If there was—suddenly Doc Turner's hand dropped from the door handle. It was two or three hundred to one. He turned, plunged into the forest, and faded eyes that had not known tears since their blue was bright as a jay's feathers were wet with tears.

A SILVERY brightness struck into the leafy shadows of the

forest. Doc went more slowly, stopped just within the edge of the

woods. Below him that silvery glint widened into the gleaming

surface of a little lake whose crystal surface mirrored the

soaring, green-clad peaks that ringed it. Nearer, just beyond

this final screen of underbrush through which he peered, began a

rolling expanse of greensward that dipped steeply, leveled out to

a wide, more gently sloping plateau, and ended where the lake's

ripples lapped a narrow, pebbly beach.

Small cabins were aligned in trim rows on three sides of the plateau, roofs glistening with dew. Two larger buildings closed in the lake-ward side of the great grassy rectangle these made and a smaller stood between them. A form moved out from between two of the little cabins, a man who held a rifle in his hands!

He stood for a moment, motionless, then drifted back the way he had come, but now Doc saw other rifle-armed figures pacing silently between the cabins and the woods.

Andrew Turner's last faint hope that the threat to the youngsters came from outside the camp vanished. Those armed men, making no attempt at concealment, were there to see that no boy should escape. Camp Nokomis was a prison.

No time now to wonder why, to try to fathom the meaning of all this. No time to run down the mountain to summon aid from the State Troopers, the villagers. Behind the peaks across the lake the sky was flaring orange with the rising sun. Within an hour death would strike.

But how could one old man, unarmed, save those boys? What could he do against those rifles?

Doc stiffened. The thin, black thread that slanted down out of the treetops to that little house on the lake side of the campus—could it be a telephone line? Most likely. The two big buildings must be Mess Hall and Social Hall. The camp's office would naturally be between them; the office was the natural place for a 'phone. If he could somehow reach it...

He had no woodcraft, this white-haired old man whose days since boyhood had been city-bound, whose life since young manhood had been circumscribed by the four shelved walls of a drugstore. He had no woodcraft, but his need was great and somehow he contrived to slip silently through underbrush that rustled at the slightest touch. He passed the end of the Recreation Hall and, crouching low, still unchallenged, reached shelter of that tiny office building.

The entrance was on the other side, facing the campus, but here right above him was a low window, and it was open.

Approaching footfalls, somewhere behind, sent him squirming through in heart-pounding haste, head first. His palms reached the floor, his legs slid in after him. His shoes scraped down the inner wall, noisy but not as noisy as the thud a fall would have made. He got to his knees, looked up in search of the telephone.

He found instead—a revolver snouting at him beneath burning, fanatic's eyes!

"Come into my parlor," declaimed a voice too deep for the slight, sweater-clad body, "said the spider to the fly." Was it the voice Doc had heard in the woods, the voice of the one Buck called boss? "Get up. Get up on your feet and keep your hands away from your pockets." He couldn't decide whether he knew the voice, but he was certain he knew the face.

It had stared at him out of a thousand pages, from a thousand posters, all spring—the face of Allan Forbes!

"I AM unarmed," Doc Turner heard himself say as he came erect,

and was surprised at the calmness with which he spoke. "Unarmed

and quite harmless. I'll admit I was somewhat unconventional in

my mode of entering."

"Don't stall." Forbes was hardly less slight than himself, Doc saw. He was considerably younger, but the inner fire that flamed in his eyes—something akin to madness—seemed to have burned all the strength out of him. "I know what you are here for." Only that steady revolver made him the master of the situation.

"Hardly." At all costs he must shield Isidore. "I am no father trying to sneak a glimpse of his son. I've read that you have many such. I'm not even acquainted with any of your lads. I—"

"Silence!" A jerk of the gun emphasized the command. "Let me think." Doc saw that they were in a small partitioned off space, saw a chair, and a camp-cot that had not been slept in. The door in the partition behind Forbes must lead to the office the old druggist had been seeking. "I must think what to do with you."

The room suddenly was filled with golden light and music. The clarion notes of a bugle penetrated the walls, blowing reveille. I can't get 'em up, I can't get 'em up... But it was getting up. There was a stir outside, an awakening.

"Why do anything," Doc tried again, "except have me thrown out of camp? That will be bad enough, having to go back to that slave-driving Simon Legree of a city editor and confess I didn't get my story after all."

"Editor!" Forbes' tension seemed slightly eased. "You're a reporter?"

"Yes. They told me to get into a Buddies, Incorporated Camp and find out—" his eyes shot to Forbes'—"if there's any truth to the rumors of something wrong—"

"Wrong!" The barbed arrow had found its mark. "What should be wrong?" Fear, distinctly fear, showed in those burning eyes.

Suddenly there was a knock on the door. "Uncle Allan," a fresh young voice cried. "Uncle Allan!"

Forbes' gun went into a sweater pocket, but the bulge thrust at Doc. "Stay exactly where you are," he whispered. He called aloud, "Come in!"

The door opened. A browned, healthy-looking youngster in green shorts, scarlet sleeveless jersey, stepped just inside. "Uncle Allan, Uncle Fred sent me to ask you—Doc!" Oh Good Lord! Black, kinky hair, hooked nose, thick lips—everything else changed beyond recognition, but these features—"Doc Turner! You—"

"Get out!" Allan Forbes' command cracked like a whip-lash. "Get out of here, quick. Go to your place in the Mess Hall and say nothing or you'll regret it." Terror leaped into Isidore Krupinsky's face, and then the door had slammed on him and Forbes was turning to Doc, his fleshless lips curling in a sneer.

"So you're unacquainted with any of my lads," he said softly, and then his voice lifted again. "Tom! Tom, get a rope and come in here."

ONCE more the door opened. The hulk of a huge Negro filled the

opening.

"Tie up this man, tight," Forbes snapped. "Hands and feet. Tie him in that chair." The Negro advanced, grabbed hold of Doc, and Doc could think of no way to stop this. Presently he was in the chair, tied inescapably to it. Forbes tested the knots and said, "Now, Tom, you stay here till I come back, and watch that he doesn't get away. Take my gun." He handed it to Tom and was gone.

"Look here, Tom," Doc said. "What's going on here?"

"Ah don' know nuffin'." The black was looking at the revolver, and it was evident that he didn't know one end of it from the other. "Ah don' say nuffin'."

The old druggist was too experienced with men to waste further effort on Tom. He'd do as he was told by his employer, and he would not talk. A creak took Doc's eyes to the door and he saw that it was swinging open.

There were desks beyond, and on one of them was the telephone Turner had risked so much to reach. The outer door was also open and through it he could see the campus, across which some figures in green and scarlet were still hurrying.

That stalwart young man diagonalling toward the Mess Hall at a trot—even divested of his sweater and wearing the same sort of green shorts and scarlet jersey as Isidore, Doc recognized him as one of the riflemen. But he was carrying a tennis racquet instead of a gun!

"'Lo, Hugh," greeted a voice beneath the window behind Doc. "Am I glad that night is behind us."

"You and me too, Ben. Say. I think the kids are wise to us. I saw that Pierson brat hanging around the shack where we cache the rifles, and he beat it like a flash when he caught sight..." The voice died away.

That was queer too. Why were they hiding the guns when, within this hour that was almost up, they—Doc straightened. The blood drained from his lips.

A car had shot onto the campus from the road, followed by another! They were streaking straight toward the Mess Hall, and they were packed with hard-faced men. Another car—no, a truck!—a huge covered truck was following them.

THE cars were out of sight now, past the door, but Doc could

hear brakes screeching. Shouts. A shot, and a sudden, dreadful

silence, into which burst the Negro's "Wah' dat? Wah' dat Ah

hears?"

"All hell breaking loose," Doc snapped. "What a fool I've been! Get out there to the telephone, Tom. Get the operator and tell her gangsters are attacking the camp. Tell her to send out an alarm."

"Yas, suh." Tom lumbered out, clawed the receiver from its hook, whirled a little crank. There was no bell-tinkle, nothing. "Hello! Hello!" He was looking back at Doc. "Dey ain't no ansuh."

"They've cut the wires," the old man groaned. "Naturally." There was another shot outside, and another, and a shrill scream of terror. "Your gun, Tom. Grab your gun and go out there and fight for those boys."

"Fight? Ah'll fight, mistuh, but Ah don' know how to shoot dat gun." The black was wheeling toward the outer door, his clasp knife flashing light.

"Wait! Tom, wait!" Doc implored. "I can shoot the gun. Cut me loose!"

"But Mistuh Fohbes say—"

"Damn Mister Forbes! He thought I was one of them, and I thought that he—If you don't cut me loose you'll burn in hell forever. You'll burn—"

"Don't cuss me. Don't put dat cuss on me!" Tom was lumbering back. "Ah'll cut you loose." His knife slashed the rope and there were no more shots. He heard the voice of the man in the woods, barking commands. Then Doc was free, pushing up out of the chair. That was not Forbes' voice. The old man snatched the revolver from the cot, twisted to follow Tom out. It was all clear now. The night patrol had been formed because somehow the camp had gotten warning of an attack, but they'd been sure it would come only at night. They had hidden their rifles by day so as not to alarm the boys.

Tom went out of the door, roaring. Crack! He was down, he was crawling. Crack, crack, crack! He sank in the dust of the cinder path, quivered, was still.

Doc checked himself just inside the door. They were watching it now. If he poked his head out... But there was a window, on this side, looking toward the Mess Hall. He got to it, peered out careful to show only his eyes.

The two big cars and the truck were standing about five yards from the pavilion. Three hard-faced men, each with two guns, were between them and the dining hall's entrance and two forms in scarlet and green sprawled in the dirt, motionless.

Allan Forbes was backed against a wall, hands at his throat. Right at the entrance stood a slighter man in immaculate grey, and he was questioning the big-eyed, white-faced youngsters who were being brought out to him by still another armed gangster. Some he sent back into the hall, some he passed on to the three men outside, who prodded them into the van.

He was separating the sheep from the goats, the slum-lads from those whose parents would pay a huge ransom. This was kidnapping de luxe, mass kidnapping with millions of dollars as the prize!

DOC'S hand lifted his revolver. Aim now, aim carefully. The

boys were passing between him and the gangsters, shielding them.

But the cars were between him and the boys; the truck was

broadside to him!

Doc's gun cracked, cracked again. And the burst of a tire drowned the second crack. Again and again he pulled the trigger. Those explosions weren't all tires blowing out, they were guns firing at him. Bullets smashed through the thin walls of this shack. Splinters plucked at Doc somewhere. Never mind. He had to hit the truck's tires...

He missed. No. The tires were solid. They wouldn't blow out. The engine then. Red mist was in front of Doc's eyes. He blinked it away and squeezed trigger. He squeezed again, and the red mist wouldn't blink away. The mist got darker, blood-red. The night... was... all red...

Sirens howled in the red night. Shouts came from far away. Shouts and shots. Let me sleep, Doc thought. I'm tired, I want to sleep... A voice was calling, "Doc!" Jack's voice calling. "Doc Turner!" Jack was dead. So Doc was, too. Jack and Doc Turner were meeting again on the other side of the Veil. "Doc!"

The red mist cleared and there was Jack's face. Behind Jack were other figures, big-hatted, green-uniformed...

"Jack," Doc Turner mumbled. "Jack, son—"

"It's all right, Doc." Jack's arms were around him, his head was on Jack's shoulder. "We came in time, thanks to you." In time? For what? "The fire warden, in his tower on top of the mountain, had watched our car's lights traveling, saw them blink out and heard the crash. He climbed down to see what had happened, reached me as I was coming to, just at sunrise. I—we heard cars passing the fork in the road and saw they were full of thugs. They were going toward the camp and we tumbled to what was going on. The warden carries a 'phone set to use while fighting forest fires. He tapped in on the line, called the State Troopers and a posse from the village. We caught the mob, rounded them all up, but they would have gotten away clean if it hadn't been for you delaying them, peppering and puncturing a couple of gas tanks."

"The boys?" Doc whispered.

"Couple clipped by flying bullets, but nothing that won't heal. I've just been talking to Izzy. Two nights ago Izzy and another little devil sneaked out for a midnight swim. They saw the armed counselors patrolling the camp, and were scared to death. Izzy was afraid to ask what it was all about, and knew his letters were read, as they are in all camps. So he thought up that cryptic message to you."

"Forbes. Must have got tip... Why didn't... he... get police?"

"It would have gotten into the papers, scared everybody. All the parents would have rushed to pull their kids out of all the camps. The whole thing would have gone up in smoke."

The mists were closing in again, but they weren't red, they were green, the color of the mountains. The color of peace. Doc sank into a quiet sleep from which he would awaken to the plaudits of a hero's fame.

But his greatest reward was the kiss that was planted on his lips by the withered lips of Reba Krupinsky when he was out of the hospital and back in his ancient drugstore on Morris Street.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.