RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

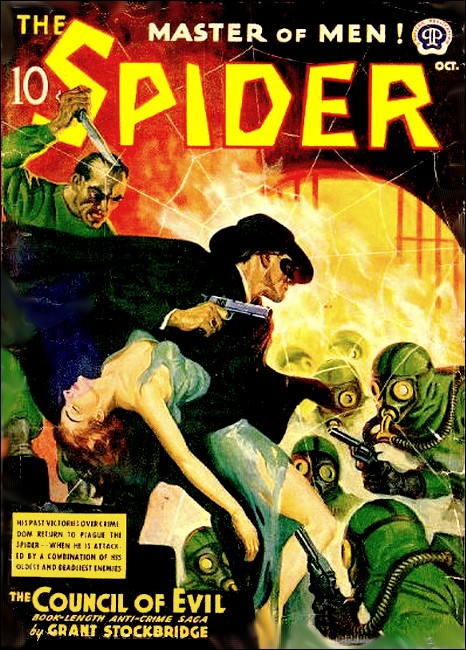

The Spider, October 1940, with "God Bless America!"

The M.E. called it heart failure. But Doc Turner, beloved benefactor of Morris Street's poorest element, saw in that pitiful old woman's corpse... murder—and a diabolical plot that promised to destroy the nation!

ORDINARILY Andrew Turner can be found in the doorway of his

ancient pharmacy. He is a small man, whose faded blue eyes have

looked with compassion upon the people of Morris Street for many

years.

So many years had he listened to the rumble of the "El" trains, the hoarse shouts of the hucksters, the jabber of the shabbily clothed aliens, that tonight he did not consciously hear them.

Familiar, too was every swarthy, foreign face. Almost better than he knew himself, Doc Turner knew these people he'd served for many years. He could call them by name and could actually pronounce those names properly: Rico Paglieri, Andrea Niestowicz, Greta Helwig, Anaxerxes Xenassian. He shared with them their joys and griefs. He advised them in bewildered struggles with the strange ways of this strange land.

A woman came around the corner from Hogbund Lane, short and wiry, sharp-featured, unmistakably French. Her black eyes were red-rimmed with weeping over the fate that had crushed her Motherland. "Juliette," Doc called to her. "Juliette Bernos. Come here a minute please."

She pushed toward him through the jostle of the crowd. Her shoes were broken and the flowers of a once pert little hat were mangy, but still there was something of Parisian verve about her. "Oui, docteur? You want someseeng?"

"Yes, Juliette." Turner gestured to a pair of horny claws that protruded from the paper bag she hugged to her bosom. Her hands were speckled with the needle-pricks of her seamstress' trade. "How much a pound did you pay for that fowl?"

The lines of Madame Bernos' face tightened, but she answered, "Twenty-sees cent."

"Look!" Doc pointed across the street to a shining plate-glass window behind which hung red sides of beef. "Didn't you see Otto Klingel's sign?" Papers pasted on the window had been painted with huge numbers. "Didn't you know that he's charging only twenty-three cents today?"

"Oui." Madame Bernos was looking at the ground. "I know."

"That bird you've walked four blocks to buy weighs about six pounds. That makes eighteen cents more than you'd have had to pay Klingel. It takes you an hour of hard, hard work to earn eighteen cents. You need every copper you make to feed your husband and your children. You've dealt with Otto for many years and you know he sells good chickens."

"Ze shicken from heem, eet would shoke me an' Pierre an' our shildrens." The seamstress did not raise her voice, but it was concentrated with fury. "Rather we all starve zan geeve one cent to zat peeg of a Nazi!"

"I thought so," Doc sighed. "I thought that was why so many women around here have stopped dealing with Klingel. But you're being unfair to him, Juliette—"

"Unfair!" Her head lifted and into her eyes there leaped a flame of wrath. "Ees what he an' hees kin' do to my people fair?"

"Not Otto, my dear." Turner interrupted. "Nor Otto's kind." He laid his gnarled fingers on the seamstress' arm. "Listen to me. Otto's no more a Nazi than you or I, Juliette. He's been in this country for thirty years or more. For thirty years he's run that butcher shop across the street and I've always known him as a good, hard-working man who's minded his own business."

"Hees own business!" In Madame Bernos laugh there was madness. "Weel you Americaines nevaire learn nossing? Otto Klingel mind hees own business, but w'at ees zat business? To be a bootchair? Non! Zat ees ze mask. Klingel ees a spy. A saboteur. A—how you call—a Feeft Colonne."

"Oh nonsense!" The druggist was exasperated. "Otto is never out of his shop. He works from early in the morning till late at night. He even eats and sleeps in the room behind it. What's he spying on, the pushcarts? What's he going to sabotage here? The "El"? I never heard anything so silly—"

"Nonsense, ees eet?" The seamstress' neck thickened, her eyes bulged. "Silly?" Her voice had gone shrill now. The Morris Street crowd was turning to gape at her and was closing in on them. "Let me tell you Docteur Tournaire, how silly eet ees. From ze weendow w'ere I sew w'ile you others sleep, I haf see ze dark forms steal eento zat alley zere," she jerked her finger to the alley, beside Klingel's shop.

"I haf go—go..."

SHE choked. The paper bag thumped to the sidewalk as her hand

fumbled to the back of her neck. Before Doc could catch her she

slumped down, and lay as still as the fowl that had spilled out

of the bag.

Doc went down on his knees. He could detect no pulse in the woman's wrist.

"Dead is she?"

Turner looked up at the woman who spoke. "I always said she'd be took off by a stroke, the way she's always screaming at her man. Crazy jealous of him she was. As if any decent woman would look twice at a puny, frog-eater like him."

Pierre Bernos was a dishwasher in Ginsburg's Kosher Restaurant whose kitchen door also was reached by that alley, and her "dark forms" might mean women. "An' now what'll he be doin' with that motherless brood of his, poor thing?"

"You'll be helping him with them, Maggie Reilly." Doc's smile was bleak. "And so will all the other women around here." He rose to his feet.

Juliette Bernos was dead. It could not harm her now that her neighbors should ascribe her death to a fit of jealous rage. Better it had ended as it did. Her wild imaginings could not bring trouble to the blue-eyed, pink-checked butcher whom she had so absurdly seized as a focus for her delirium. "But the first thing we'll have to do is send for an ambulance so that their mother can be officially pronounced dead. Tony, and you, Staroff! Please keep the crowd away from her while I do that."

THE old pharmacist went into his store, turned to the 'phone

booth. As his nickel clinked into the slot, a sudden thought

paled him. Apoplexy occurs in thick-necked, burly individuals.

Madame Bernos had been fleshless, wiry. The crowd had been

pressing close to her at the moment she'd been

stricken—

But neither the interne who came on the ambulance, nor the physician from the medical examiner's office had found anything suspicious when they'd examined the corpse. They gave permission to have it taken away.

Life is not so precious on Morris Street that death, however sudden, should make more than a ripple there. Later that waning Friday afternoon Doc Turner resumed his post in his store's doorway. The incident might never have occurred for all the difference it made in the tumult. Nevertheless the old druggist was still thinking about it, his wrinkled visage sober. Suddenly it brightened.

"Jack!" he exclaimed. "Jack, my boy. What brings you around at this hour, all dressed up like it's Sunday? I hadn't heard that the Hogbund Lane Garage had closed up."

"Neither had I, Doc," Jack Ransom grinned at him. "It's still doing business, but without me."

Turner looked concerned. "Don't tell me John O'Mara has discharged you! He wouldn't deprive himself of the best mechanic in the city."

"Wrong again. John didn't fire me."

Ransom was perhaps a third the pharmacist's age, a barrel-bodied, carrot-topped youth with a spray of freckles across his nose. Between these two, despite the difference in age, there was a deep affection. In Turner's forays against the underworld Jack was his strength.

"So you resigned? Worse and more of it! I suppose you flew off the handle at something he said."

"Well," Jack grinned reminiscently. "I certainly put on a good act in front of the customers."

"I can well imagine. Now, you listen to me, you hot-headed young fool. You're going to march right back around the corner, apologize and get your job back. You'll never get another one as good."

"Whoa, Doc! You're up in the air. I'm not going back, and I have got another job." Ransom sobered. "Come inside. I've got something confidential to tell you."

THE tightness in the line of Jack's jaw told Turner that he

was suppressing some unusual excitement. In silence Jack followed

the druggist to the immaculate prescription room.

"All right, Jack." The old man turned to his young friend. "What is it?"

Ransom rubbed a thumb along the edge of a table. "I said before that I put on an act throwing my job in John O'Mara's face. That's just what it was; I had to quit him. I couldn't tell him why."

Bewilderment deepened the wrinkles around Doc's eyes.

"I'm not supposed to give anyone the inside of this thing," Jack continued. "But I know damned well that what you hear is going to be kept to yourself. I just couldn't duck out on you without telling you what's up."

"You're going away somewhere?" the druggist asked.

"Not far, Doc. Not more than a block from here. But once I get there, I'm not coming out again for a couple months—maybe longer, and I won't be writing letters."

The old pharmacist shook his head. "I don't understand."

"If you'll give me a chance—You know that factory back on Lee Street? The Acme Hardware Works?"

"Of course I do. Don't a hundred or so of the men around here work there?"

"Used to work there, you mean. Monday was payday, and every alien on the payroll was given his pink slip. You must have heard that."

"Why! No one told—" Doc broke off. "Good Lord, Jack! That's not right. America has to defend herself—make herself so strong that Hitler and his pack dare not attack us, but that's no reason for firing every poor dub who hasn't taken out citizenship papers."

"Hold it, Doc. Hold everything. Nobody's firing aliens just because they're aliens. But if there's a chance that a foreigner can do a lot of damage—"

The old man laughed, humorously. "What damage can anyone do the country in a factory that turns out brass doorknobs?"

"None. But the idea is that Acme is going to turn out something a damned sight more important than doorknobs from now on. All the aliens working there were fired on Monday. On Tuesday a force was already busy in that plant getting it ready to make—well, a certain little gadget. It's no bigger than your fist, but it's all-fired important to the operation of the fifty-thousand planes a year that we're starting to manufacture in other plants, all over this country."

"Ah," Doc nodded. "I'm beginning to understand. Go on."

"Most of the machinery in there already can be changed over to make this gadget, but there's one part of the operation that's brand new, and the machines they're putting in for that part have taken six months to build. Now, this is the only factory that's being equipped to turn out this particular item, so if it's put out of commission—"

"It would delay the completion of the airplanes for six months," Turner put in. "A net loss of twenty-five thousand planes, in other words."

"Right! Which is why we can't afford to have a single man in that building we aren't absolutely sure of. The mechanics who're going to operate those machines have been hand-picked. Their records, from the day they were born have been gone over by the F.B.I. To make absolutely certain we can't be gotten at by Fifth Columnists, we're not even going to be permitted to leave that building once we go in there, an hour from now."

"We! You mean that you—" the druggist was interrupted.

"That I'm one of them. Yes." Ransom straightened with pride as he spoke. "It's going to be a tough grind, Doc, but I can take it."

"Yes, you can take it." In his faded eyes shone a new light that had not been there for decades. "You can take that grind better than you and millions of young men like you can take the battering of bombs. It would be their lot if America doesn't make herself so strong that no one will dare to attack her. You and thousands like you, Jack, are building a war machine that will assure peace to America."

IMMEDIATELY after their good-byes there came a rush of trade.

By the time Andrew Turner had sold his last bottle of cough

medicine and had filled the last capsule, a tower clock somewhere

was intoning midnight.

Washing at the sink in the prescription room, the old druggist thought of how much he was going to miss Jack. He was missing him already. Unless the young man had something else to do, he'd always drop in along about eleven, for a smoke and a chat. Tonight for instance, Doc would have talked of Juliette Bernos' hysterical notions about Otto Klingel, the old German butcher.

Doc's hands were suddenly rigid. He recalled the questions he'd flung at the woman. "What's he spying on? What's he going to sabotage, the "El"?" There was something here, directly behind Klingel's store, for him to spy on. There was something. The machines in the Acme Factory that it would take six months to replace!

A CHILL prickle scampered the old pharmacist's spine. Then he

was laughing at himself. What utter rubbish! Klingel had opened

his shop here thirty years ago. The Germans would have to be more

than geniuses at espionage. How would they have known three

decades ago that in 1940 this would be a strategic position for a

fifth columnist.

He finished wiping his hands, hung up the towel. He thought: what if Juliette really had seen "dark forms" skulking into that alley to Klingel's back door?

Doc turned out the lights in the rear, ambled out to the front of the store and turned out more lights. The questions continued to hammer, insistent, at his skepticism. What if the furtive visitors were not figments of Juliette's overwrought imagination? What if she really had seen them? What was it she'd been about to say?

What sort of death was it that had silenced her so suddenly? Cardiac failure, the physician had said.

Turner's key rattled into the lock of his drugstore's outer door. It was unthinkable that the genial Otto he'd known so many years could be sinister, but almost everything that has happened this past year, has been unthinkable. It was true that, like many of his countrymen, Klingel retained a peculiar attachment to his native land. He still read a German newspaper. As long as possible he had written regularly to his sister in Posen, and always been happy when she replied.

Doc Turner finished locking the door, turned as he put the key in his pocket and peered across the street at the butcher shop.

The pushcarts were gone and the whole block was dark, lifeless. In the black mouth of the alley there was a flicker of movement! A merging of shadow with shadow, sensed rather than seen.

Doc Turner came to a decision.

FIFTEEN minutes later he was drifting, a silent shadow, along

the unlighted area that ran between Klingel's Meat Market and

Ginsburg's Kosher Restaurant. The stench of garbage was pungent

in his nostrils. He could hear no sound, see no living thing, not

even a stray cat. He reached the end of the butcher shop's brick

wall, crouched warily, and became aware of a murmur of guttural

voices not far distant.

They could be coming from any one of the rear flats of the tenements whose ground floors the two stores occupied. The night was warm and windows were open. Doc straightened, went around the corner into the debris-strewn backyard the other side of which was a high wall of the Acme Hardware works.

From behind that wall came the faint thud of pacing feet. The metallic clink of gun on belt buckle. That factory was guarded by armed men!

The door to Klingel's living quarters was a dark rectangle in whitewashed brick wall. The four wooden steps leading up to it sagged, and their rail was broken. Beside the door, higher up, was Otto's window. This too was black except for a single line of yellow light that seeped out from under the black shade.

A pulse throbbed in the druggist's seamed cheek. The half-heard voices were coming from within that window, and from within it came another sound, a slow scrape, scrape, scrape that set Doc's teeth on edge.

He started moving again. The bottom of the window was above his head. From a box under it came a stench of decayed meat. The box had no top. The voices had stopped. He was afraid of revealing his presence, but he had to risk it. He placed his feet carefully at opposite corners of the box, steadily as possible, and raised up. His eyes were level with the slit through which the light came.

The sash was open about a half inch. The light blinded him for a moment, then his vision cleared. He was looking into a fairly large room, could see the central half of it. Directly opposite him was a wooden kitchen table. On this a newspaper had been spread and there lay a row of gleaming butcher knives. Near the far edge of the table lay a large whetstone. Along this, back and forth, two pink hands drew the shiny blade of a knife.

The hands belonged to a man sitting there in shirt-sleeves, collarless. Otto Klingel's eyes were the pale blue of a doll's.

Not so innocent-looking was the man who leaned back in another chair, cigarette drooping from the corner of his mouth. Very much younger was this one, his lean face gaunt with an odd, frightening brutality.

His stub-fingered hand took the cigarette from between his lips. "You're getting white around the gills, Otto." His speech had no trace of foreign accent, but there was a guttural intonation that told he was not American-born. "You aren't getting cold feet, by any chance?"

Klingel drew the knife he was sharpening back and forth. "Nein, Carl. I am not getting cold feet. Only I am thinking, if something should go wrong."

"You'd better make sure nothing does go wrong." The sadistic lines of Carl's face deepened. "Just remember your sister in Posen and her three children. Just remember what will happen to them if anything goes wrong here through your fault."

"Dot I am. All the time I think of my loved Anna and her children."

Doc Turner's mouth was dry. That brief conversation had told him enough. It told him that his old friend had turned traitor to the land that had sheltered him so long, and it also had told him why.

The arm of the Gestapo is a long one. Its hand holds a terrible weapon to force men to its will.

"Through mein fault," Klingel's hands went back and forth, sharpening the knife, "nodding will be wrong. But dis ding what happen dis afternoon, dis ding mit Chuliette Bernos, I don't like."

"Forget that. She might have done plenty of damage if I hadn't been there. I heard what she was saying and I stopped her before she said anything to give us away." Carl's smile vanished and something wolfish, diabolical, replaced it. "A quick stab with a cyanide hypodermic works instantly. I had to shut her mouth."

"So," Klingel murmured. "So. Dot wass how you did it?"

"That was how. And those stupid doctors never bothered to examine her properly. Wouldn't have seen the little needle prick even if they had."

Doc was sick. If only he hadn't been so certain that Madame Bernos was out of her mind with grief over her beloved France. A door he hadn't noticed before was opening behind Otto Klingel. Otto didn't turn, didn't stop the slow motion of his hands, but Carl's feet dropped to the floor and he was up out of his chair.

"Well," he demanded of the man who'd come in. "Well, Rudolf? Are you set?"

"Soon as I get these wires attached." Rudolf was a little huskier than the inquirer and his clothes, his face, were smeared with brown earth, but otherwise he was a counterpart of Carl, even to the bristling blonde hair. "You did a good job on that tunnel."

He moved to the table, and Turner saw the two wires that trailed from his hand and out through the door he'd just entered. They were threadlike filaments of bare copper, finer than any the druggist had ever seen.

"Damn right we did a good job on the tunnel. Took us two weeks, didn't it? If you've done as good a job, everything will be swell."

"Don't you worry about me." Rudolf put the coil on the table, next to the whetstone along which Klingel's knife scraped with a horrible, nerve-tormenting placidity, and Doc made out that a small switch was spliced into one of the wires, that they ended in a screw-plug for connection to some electrical socket. "I've got the charge right under the pillar supporting the floor where the machines we're interested in stand. There's enough to smash the whole factory into dust."

DOC'S fingers were so tight on the sill to which they clung

that the rough stone merged with flesh. So they'd dug a tunnel

from the basement. Under the very spot where he was standing,

under the wall and the sentries that guarded it, under the Acme

plant. And they'd planted a charge of explosive there to smash

the building. To smash the machines it would take six months to

replace. And Jack Ransom was in that building!

Rudolf reached up to the chandelier above the table and was screwing the plug into an empty socket. "Into dust," he was repeating, "and the current will turn this wire into vapor the next instant and the tunnel will be obliterated. When I pull that little switch—"

"Not you, Rudolf," Carl had moved to the left, was out of Turner's sight. "Otto here has instructions from our Leader that he wants the honor of setting off the first blast in our campaign himself. We're to wait for him."

A sigh of relief was exhaled from between the old druggist's teeth. They were going to wait! He had time yet to get away from here, to get across the street to the phone in his store, call a warning to the factory, summon help from the police, the F.B.I. He was off the box and was darting soundlessly around the alley-corner—He ploughed into something yielding and felt a steel-like grasp on his arm, a palm fold over his mouth to stifle the yell that was half-formed in his throat.

Doc heard a startled whisper above his head, and was being held away from someone who seemed incredibly large.

The grip on the druggist's arm was tortured and robbed his frail little body of what little strength it possessed. The man spoke: "Come. I must see who prowls where it is dangerous to be this night."

Turner was lifted from the concrete. He was being carried, dangling, back the way he had come, back past the window and up the sagging steps to Otto Klingel's back door. The man uttered a low whistle. He saw the light blink out and heard the click of a lock, the low rasp of oiled hinges, and he was being carried inside.

"I found this creature running away from here." The tones were cold, accusing. "You are careless, Carl. Too careless."

"I had no idea, Gauleiter—"

"I am not interested in your ideas. Your fault I will punish when I have done what has to be done. Meantime, see that this one is rendered harmless." Doc was thrown on a bed and Carl was on him, stuffing a handkerchief in his mouth, binding his wrists and ankles.

Finally, the old druggist was helpless. Carl rose, clicked heels and was rigid beside Rudolf who also was stiff at attention. The man who faced them was tall, but had the air of a demigod rather than a mere human. He smiled grimly. "You are ready?"

"We are ready, Gauleiter." Rudolf indicated the wires dangling from the light fixture overhead. "All is prepared."

Turner recalled that Gauleiter meant "Little Fuehrer."

"And you, Klingel?" The Gauleiter turned to Otto who still sat at the table.

"I know. I am to unscrew the plug, destroy it and der svitch, which will be all of your infernal machines left. I vill rave against the devils who haf done dis ting." He spoke as if by rote, his attention on his endless task. "Andt if some vay it is traced to me, I vill say I dit it all meinself, mein own idea."

"Right. You will remember your sister Anna in Posen, and her children, Gretchen and Kurt and little Elsa."

"I will remember," Klingel sighed, scraping the blade back and forth.

"Yes," the Gauleiter nodded, his eyes narrowing. "I think you will." He moved to the table. "For the Third Reich," he murmured with fanatic devotion as his hand took hold of the switch's handle.

Doc's scream was muffled by his gag as the huge hand pressed down on the switch.

KLINGEL'S knife scraped. The others were staring at one

another. The wires still hung from the chandelier to the switch

on the table and trailed out of the basement door. There had been

no sound of an explosion.

"What?" the Gauleiter murmured. "What is this, Rudolf?"

"There must be a break in the thin wire, somewhere." A pale sheen of terror crept over the man's face.

"Find it," their leader shouted.

Rudolf moved. He pulled open the switch, then went around the table. He rose with a severed copper filament in his hand. "Look," he gurgled. "It was Klingel who cut it." Otto's hand moved with amazing swiftness. The knife in it buried in Rudolf's ribs.

"Yes," the butcher's voice rumbled. "I cut the wire while the light wass out." And the scarlet blade hacked again chopping the wires into shreds before they could slide from the table. Klingel rumbled on, "Do to my sister vot you vill, dis gountry dot has been so goot to me—" The crack of a gun cut him off. The gun in the Gauleiter's hand cracked again, and Klingel toppled against the table, crashed over it. The knives clattered to a heap atop the corpse of the man the butcher had stabbed. One knife hit the floor and bounded to the bed on which the old druggist lay.

"So to all traitors," the moon-faced giant grunted. And then he was turning to Carl. "Splice those wires together. The switch is intact. We can still finish the job."

Otto Klingel's fat form rolled over. His hand came away from the sodden scarlet of his chest, pawed at the man who crawled alongside him. Carl struck at him brutally. There was a squash of bone on flesh and the butcher lay still.

For a while there was no sound except the heavy breathing of the two men intent on knotting the wire-ends together.

So intent were they that they did not see the little pharmacist as he laboriously used that knife on his bonds.

Then the Gauleiter sighed, "So, we are finished and no police come. No one heard the shots." He reached for the dangling switch. Doc leaped past him, slashed the wires with the knife that had freed him.

CARL rasped an oath, struck at the old druggist and received

the steel blade in his throat. He dragged the hilt from Doc's

hold as he went down, and the Gauleiter's brutal hand

gathered the front of Doc's coat.

The little pharmacist kicked air, flailed with impotent fists at the rigid arm from which he hung. He made muffled sounds behind the gag he'd not stopped to pull out of his mouth. The spy-master's eyes glowed with fury as he growled, "I can still patch the wires. You have gained nothing except this kind of death!" His other fist lifted the automatic, reversed to a club over Doc Turner's white-haired skull—The Gauleiter screamed shrill agony and collapsed like a pricked balloon, his ripped abdomen gushing a ruby torrent. Behind his enormous quivering frame was the figure of Otto Klingel, poised on fat knees, the blood-drenched cheeks no longer pink but gray with the shadow of death. The biggest of the knives dripped ruby liquid from his fingers.

Doc Turner picked himself up from the floor, tore the handkerchief from between his teeth and stooped beside the butcher. "You couldn't do it, Otto. You couldn't go through with it, could you?"

A red bubble formed on Otto Klingel's lips. "No." It was the merest shadow of a voice. "I nefer—meant to. I led dem on to trap—deir Fuehrer. Wen he 'phoned me dis afdernoon—I t'ought he meant tomorrow." The fat form swayed, but Doc's arm around its cushioned shoulders held it. "Found out—tonight—too late..."

The light in the china-blue eyes went out. The body sagged against Doc. But the graying lips whispered a final sentence. "Gott bless—America." And then they were stilled—forever.

Doc let what remained of Otto Klingel down gently to the floor. He rose wearily, got to the window and let up the black shade. Looking across a debris-strewn yard at a spike-topped wall, and at the factory looming up behind it, he spoke. "Jack, my boy," as though Jack Ransom, sleeping safe behind those silent walls could hear him. "The Fifth Column almost destroyed you tonight, but the Sixth Column saved you."

Then he turned to the shambles in the room. His tired eyes saw only Klingel's face, blood-smeared, bruised, but somehow peaceful and content. Andrew Turner's gnarled, acid-stained fingers lifted to bow in a salute. "God bless America," he whispered. "And may God reward you, Otto Klingel."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.