RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

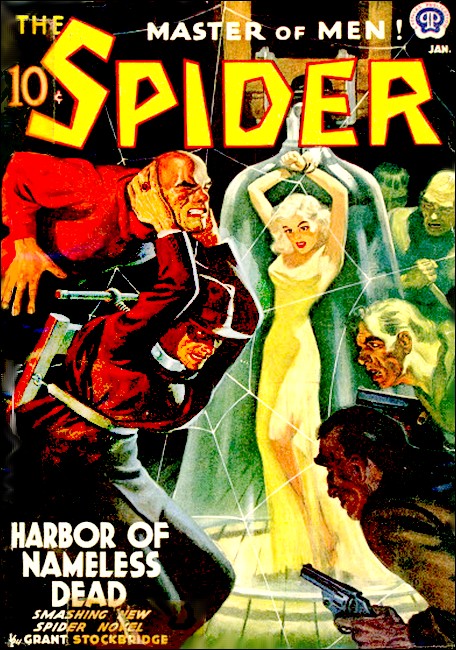

The Spider, January 1941, with "Doc Turner and the Heads of Death"

Why did the slum-folk of Morris Street cringe at the sight of beautiful Nanya Karista? Doc Turner understood their fear only after the tired old druggist had tracked Nanya to the lair of the Old Ones—where the dread witchcraft of savage jungles held full, hypnotic sway!

THE frail beauty of Nanya Karista was incongruous with her

slum surroundings. It was like a delicate spray of Queen Anne's

Lace, Doc Turner thought, in a field overgrown with weeds. A

brief smile brushed the lips under his silvery mustache. He was

pleased with the fancy that came to him as his faded blue eyes

watched the girl across the street. Strange, lovely, Nanya

Karista...

The old druggist had never before realized how much there was in common between Morris Street and some steaming equatorial jungle. The shadows of the "El" on the dusk-darkened cobbles might well be cast by towering tropic foliage. The jungle's garish colors were matched by the yellows of the lemons piled on the pushcarts lining the curbs, the crimson of the tomatoes, the brilliant greens of the spinach and lettuce and cabbage heads. The hucksters' cries were as raucous as the squawks of parrots and macaws. The polyglot chatter of the alien crowd was like the jabber of a monkey troop.

In the moment before he had glimpsed Nanya Karista come out of Hogbund Lane, Doc Turner's broad forehead had been lined deep with troubled speculation. The sixth sense born of his long years of befriending the friendless people of this slum had warned him that the black pall of some new dread hung over them. He was standing before the door of his ancient pharmacy in the hope that some chance word overheard, some impulsive confidence from one of the many who loved and trusted him, might give him a clue to its source.

But the stocky, swart-complexioned men plodding wearily homeward from factory or ditch, the shawled housewives bargain-hunting from cart to cart, had greeted him only briefly and hurried on. It was precisely this furtive haste, this obvious avoidance of talk with him, that confirmed Doc's feeling of something wrong, deadly wrong, on Morris Street.

He had lived among, served, these people for too many years, had abandoned too often his role of pharmacist to battle the many schemers who prey upon the helpless poor, not to know their habits. They had brought here from the four corners of the earth different folkways, but in one they were all alike. Threatened, afraid, they hugged their fear to themselves and no one not of their own kind, not even Doc Turner, could penetrate the curtain of silence they drew over their dread.

Across the street, Nanya Karista reached the curb. Doc gasped!

Without a moment's hesitation, the girl had stepped out into the stream of hurtling trucks and cars!

A monstrous van loomed toward her. Its headlight blaze glared full on her and to Doc Turner Time seemed suspended so that he might see and remember of every detail of the girl's beauty before it was smashed to extinction.

Tall for a woman of the slums, she was made to appear taller by the white folds of the skirt that flowed to the ground from a tight velvet bodice that, black as midnight, clasped the firm, lovely curves of young womanhood.

Her hair was a misty, blue-black cloud framing cameo-sharp, tiny features, sensitive, wistful, her skin unblemished, so white, so transparent as to seem aglow with some inner light. Long, black lashes veiled her eyes as she glided through that roaring tumult, apparently oblivious of her peril.

BUT the driver of the huge van catapulting at her was not

oblivious. An incoherent shout burst from his suddenly gray lips

as he fought steering wheel and brake to stop his juggernaut

before it should crush the girl. An "El" pillar inches from the

van's mid-side, a beer truck on its left, made it impossible to

swerve it.

He could not check the vast momentum in time. He could not save Nanya. But she could save herself! In front of her, to her right, a quick-thinking chauffeur had twisted his sedan broadside to the traffic, had cleared a space into which she could leap—

Lost in dreams, she did not see it. Or refused to.

Brakes screeched. Someone screamed. Something dark flashed from that other sidewalk across the van's hood, now inches from her, struck her, bowled her into that cleared island of safety! The van rumbled over the place where she'd been, and she was hidden from Doc Turner by the beer truck, surging across his line of vision. But not before he had seen the big brown mastiff disentangle itself from the flurry of white and black that was the girl it had saved from certain death.

Doc darted to the curb, squirmed between two pushcarts. Nanya Karista glided out from behind the beer truck, gutter dirt marring the folds of her skirt, a gray fleck of dog-slaver on her black bodice, her white, small face as composed as though nothing had happened.

"Nanya!" Turner exclaimed. "You little fool." His hand trembled a little as it took hold of her arm, drew her to the sidewalk. "What were you trying to do? Kill yourself?"

"No." There was a girlish sweetness in her low accents, and a slurring of the syllables told that she was speaking a language not native to her. "I do not try to kill myself. That is forbidden. But," she shrugged, "if it happen—"

"You little fool! Aren't you afraid of death?" Doc cried, and in that moment was aware that instead of pressing curiously around, the throng on the sidewalk was retreating, so as to leave them alone in the center of a yard-wide vacant circle.

The long, black lashes lifted. The old druggist looked into eyes that were deep wells of dark distress. "Yes," he heard. "I fear to die. But more I am afraid to live."

"You're wha—?"

"Are yuh all right?" The hoarse bellow that blanked out Doc's exclamation belonged to the burly, dungaree-clad driver of the van. "Cripes, girlie!" He was still shaken, his heavy jowls pallid beneath their stubble of unshaven beard. "Are yuh all right?"

Nanya's lashes veiled her eyes again. "I am not hurt."

"Cripes!" The fellow pulled the back of his hand across his brow, wiping the cold sweat from it. "Cripes, that was a near thing. If it hadn't of been fer that dog—"

"That dog deserves a Humane Society medal," broke in the gray-headed, dignified owner of the sedan that had slewed sidewise to give the girl her chance for life. "And I intend to see that he gets one. Whom does he belong to? Where is he?"

There was a crowd now about the druggist and the girl, but it was made up of truck drivers and riders from the passenger cars. Not one of them belonged on Morris Street. "Who saw what became of him?" the elderly man asked. "One of you must have seen where he went to."

Surely at least one of them must have, but the faces were blank. "He was an ugly brute." A woman in a mannish suit shuddered a bit, and Doc could not blame her, recalling the massive head he had glimpsed, the bristle of black hairs about the slavering muzzle, the red-glowing eyes. "I'd be frightened to death if I met him on some lonely road."

"I'll bet the little lady here thinks different," the van's driver chuckled. "Huh girlie? Yuh watched where he went, didn't yuh?"

Turner felt a quiver in the arm he held. "He went back where he came from," Nanya murmured. "Where none of you can follow."

And then a policeman was shoving in among the crowd, bellowing, "Come on, you guys. Come on, get back to your wagons and get them moving. You've got Morris Street jammed up a mile each way. Come on. Let's go!"

The knot of strangers broke, scattered, and Doc was alone again with the girl, in the center of a strange isolation ringed by the slum people's oddly wary eyes. They seemed at once fascinated and afraid.

"What did you mean by that, Nanya? What you said about the dog?"

"Nothing. I mean nothing. I only talk foolish words." Turner knew she lied. "Please let me go." She tugged to free herself. "Please. You do not have to be afraid for me. They will not ever let me die."

"THEY!" He held her tightly and there was excitement in him

that he hoped did not show in his face. "Who are 'They?'" Was

there some connection between this girl who was afraid to live

and that which threatened the people of Morris Street? "How can

they keep you from dying when your time comes?"

"If They can send a dog from nowhere to push me from under wheels that would kill me," there was awe in Nanya's breathed tones, "is there anything They cannot do?"

"Nonsense!" Doc snorted. "You can tell that to fools, but I am a man of science."

"Yes." It seemed to him that there was a note of pity in the girl's low voice, and a note of warning. "You are a man of science and your science teaches you that some things cannot be. But the world is more old than your science, and there are things in it your science do not know. There is good in it more old, and there is—" she hesitated, found the word, "evil more old, more strong than the powers your science gives you. Do not ask to know too much, because you may find out things it is not safe to know."

"Look here, Nanya. I am not letting you go until you tell me—" Her free hand flashed up, its edge struck the side of Doc's neck sharply. His fingers were suddenly powerless and she pulled free from them, flitted away, a dart of white in the deep dusk, the crowd opening for her.

In that moment the street lights came on and Morris Street was its tawdry, raucous self again.

Andrew Turner, rubbing dull pain where the edge of Nanya Karista's hand had struck, knew at least that the momentary paralysis induced by the blow was no magic his science could not explain. There is a plexus of nerves where neck and shoulder join... A strong arm went around his back and a strong, young voice said, "Hello, Doc. What's bothering you? You look kind of dazed. What's the matter?"

"Jack, my boy." The stockily-built, carrot-topped young man who had greeted him was a third Turner's age, but there was close affection between them. "Come into the store, I want to talk to you." Jack Ransom had the strength Doc lacked, the youthful vigor, and very often the two had gone hunting together human jackals that prowled the slum's jungle. "I think that perhaps we once more have things to do."

"Swell!" Jack grinned. "Great! I've been getting bored, doing nothing but mess around with the greasy insides of jalopies in the Hogbund Lane Garage."

The air within Turner's Pharmacy was laden with ancient dust, the shelving that lined its walls sagging and yellow with paint once white, its showcases heavy-framed, their glass scratched till almost opaque. Its light was grimy, and the bare boards of its floor were gray with age, rutted with the wear of countless feet. The store was marked by the years, like its owner, but, like its owner it stood ready to serve the people of Morris Street eighteen hours a day, seven days a week.

"It was a strange thing she said," Doc mused, having finished telling Ransom about Nanya's narrow escape and what followed it. "That she is afraid to live, but the way she acted seems to prove that she meant it. She did not deliberately attempt suicide, but when she started across the street without waiting for the light she was deliberately inviting death by accident."

"Yeah." Jack's broadly molded, freckle-dusted face was sober. "What I'm thinking about, Doc, is the way that dog showed up to save her and then disappeared. If anyone except you told me that, I'd sure think he was taking me for a buggy-ride."

"I did not tell you that the beast vanished," Turner protested. "I merely said that no one saw where it went."

"Sure. And two or three of them were right on top of the whole thing. They couldn't help seeing—"

"Their attention was centered on Nanya and they might easily have missed observing the mastiff's behavior. But the girl certainly believes it vanished into thin air. I am convinced that she truly believes it was sent to save her by some—persons, powers, I could not make out whom she referred to as They. And the weirdest aspect of that is that she thinks of those who so sedulously watch over her as evil. A strange, an inexplicably strange, inversion."

"Inexplicable, hell." Ransom had decided not to be impressed. "She's just bugs, Doc."

THE druggist's acid-stained fingers drummed on the top of the

showcase where they stood. "I should agree with you, son," he

said slowly. "I should say you were right, if it weren't for the

way those people out there shunned her. They fear her, Jack, they

fear her with a deathly fear, and that has set me wondering if

that is not tied up, somehow, with the fear that has oppressed

them the past day or two."

"Huh?"

"You must have noticed it, Jack. You must have noticed that something is wrong again, around here."

"Well..." Ransom scratched his tousle of red hair. "Now that you speak of it, there have been one or two off-color happenings. Like Giuseppe Lanio selling off the flivver truck he peddles junk from, and not buying another."

"He did that!" Doc's hand closed on the edge of the showcase, tightened on it. "Lanio did that! After he starved himself and his brood, scraped and stinted for two years, to get the money to buy it! I remember how happy he was when he drove it around here to show me. He told me how now at last he could make real money, big money, at his trade."

"Yeah. He's got to go back to pushing a hand cart around now, and him with his bum back. And look, Doc. There's Bronco Padlovich, too. I heard he's pulled that boy of his, Dimitri, out of high school and got him a job lugging castings at the foundry where Bronco's a straw boss."

"And Padlovich was so set on Dimitri's studying to be a surgeon," Turner groaned. "Was dedicating his whole life to making it possible. A year of that work and the boy's hands will be ruined—The signs are here, Jack. The sacrifices on every hand, to get money for something. The all-pervading sense of apprehension. They're signs that someone is draining our people of their little resources, is extorting their pitiful savings by some diabolical threat."

"Looks like it," Ransom was very sober now. "Sure looks like it. But they won't tell us what it is."

"No. They never do, and so we must find out what it is without their aid. And I say again, the place where we have to start finding out is the place where Nanya Karista is. What do you know about Nanya Karista, Jack?"

Ransom pursed his lips. "Nothing much, Doc. I know that she showed up in the neighborhood about a month ago. A couple of times I seen her coming in or out of Potato Alley, that bunch of ratty shacks down near the River, so I guess that's where she lives, but I ain't got any idea if she lives alone or not. And—I guess that's all. You know any more?"

"Only her name, and that she has been in here several times for certain simple herbs so seldom called for nowadays that this store is probably the only one in the city where they can be purchased. She intrigued me, and I tried to find out her nationality. She deftly evaded my questioning. Till this evening my interest in her was only a doddering old man's curiosity."

"She's beautiful, Doc."

"Yes," Turner smiled. "I am not too old yet, son, to have not noticed that. But some of the most beautiful jungle plants are also the most poisonous—now why," he broke off, "should the jungle be running so much in my mind? Oh, I know. I've been reading the account of the Gill-Searle expedition to study the practices of the witch-doctors in the interior of Ecuador. It is astounding, Jack, how much of scientific benefit has been discovered in the brews of the primitively superstitious Jivaris—"

"Sure," Ransom interrupted. "I'll bet it's all very interesting and you'll tell me about it sometime, but just now I'd like to know what we're going to do about this Nanya Karista and whatever she's up to."

"You're not going to do anything, Jack," Andrew Turner answered softly, "just yet. There may be work for you after I have found out what she is up to, when I have closed the store at midnight."

AT midnight there was still a glare of electric light along

Morris Street as the hucksters nailed tarpaulins over their

depleted stocks and trundled off their pushcarts, but three

blocks to the East darkness had invested the River and the

wharves lining it. An oily fog had rolled up from the River to

enshroud the high blind wall of the warehouses along the River-side street.

The fog distorted familiar shapes till they were grim, frightening bulks in the night. It struck a damp chill into the old man's bones, shook him as with an ague of fever. But Doc Turner, crouched against the fence that divided a warehouse backyard from the broken, mud-slimed cobbles of the alley, was very glad of the fog.

He'd come here with no definite plan except that, since he knew who occupied most of these hovels, he would need to investigate only two or three to locate the one where Nanya Karista lived. But he had not needed to investigate even one of them. As soon as he'd come in here, he'd known which one it was.

The light had told him, the glow, down there at the dead-end of Potato Alley, on which his old eyes were fixed, wide-pupiled. It might be the fog that blurred it so that it had no form. The fog might be filtering some rays of the spectrum out of it, passing others through, so that its color was a livid blue-green, the phosphorescence of dead wood—or flesh—decaying in the black jungle night. But no fog could cause it to vary in brightness, now dim, now brighter, now dim again...

Doc shrugged tight against the blackness of the wall, inhaled, exhaled, shallowly and with infinite precaution against betraying breath-sound, because there were others abroad in the fog, and it was desperately urgent that they should not discover that he was there.

This was not because he feared them. Whatever secret purpose brought them here at midnight, whatever the lure of the livid light, they would not harm him. They were his neighbors. His friends. One had stubbed a toe on a misplaced cobble and sworn at it in the voice of Anton Warsoff, who hawked eggplant every day fifteen feet from the front of Doc's drugstore. The face of another had been revealed by a momentary swirl of the fog, and it had been the hawklike, swart face of Manuel Esposito, the Porto Rican porter in the hardware store down the block...

They would not harm Doc, but they would keep him from learning what it was that drew them here as a flame draws moths out of the night, to their destruction, and this he must learn if he was to save them.

For a long time Doc crouched there, so long that his clothes were sopping wet with the fog before the dark shapes ceased to steal past him. A little longer he waited, while the throbbing light faded and was gone, and then he moved toward the place where it had been.

It was the last of the shacks, a tumbledown low structure, paintless and riddled with cracks. Strange that with numbers of men within it, no light showed through the cracks, through the chinks where the ancient window sashes were warped in their frames. Strange that no sound of talk, of life, came through the thin board walls. This house was as silent, apparently somnolent, as all the others.

The throbbing light had come from here, from where a door was now a darker rectangle in the hovel's dark loom. Doc moved noiselessly around the side of the structure to its rear. By sense of touch rather than sight, he found what he sought, a slanted trap door of mouldering wood behind which, he knew, broken stone steps went down to a cellar.

These houses were all alike and when they were clean and new and had a view of the River, a much younger Andrew Turner had lived in one, boarding with a family that long ago had fled the incursion of the alien peoples who had made this neighborhood a slum.

The rusted padlock was no puzzle to the slim metal instrument Doc's deft hands manipulated. He hoped that the protest of the ancient hinges was enough muffled by the fog that those within would take it for some sound from the river. The cellar reeked of sewage. Vaguely, the pulsant green light was there, enough to show him the ladder-like stairs he looked for.

There was a door at their head, netted with cracks, and through them the blue-green light sifted, throbbing like the pulse of an enormous heart.

ONE of these chinks was wide enough to let him see what was

beyond almost as well as if the door were not there. He faced

into a short passage. The pulsant luminance came out of the

larger room into which the passage led, and the walls of this

were swathed with fold upon fold of black fabric to hold in light

and sound.

Squatted there on the floor of the room, in a semi-circle facing the black-draped wall, were somewhere between a dozen and a score of the men he knew, the men who had passed him in the fog. The men of Morris Street.

He saw their faces, set, pallid, their wide eyes shadowed a horror, but he did not stop to identify more than one or two—Bronco Padlovich, on one side of him Giuseppe Liano, on the other, and Kurt Anstalt, a fair-haired young refugee too intelligent to yield to the Nazi terror—because he'd followed the upward direction of their gaze.

The ceiling was swathed with the black fabric too, but cords of some vegetable fibre dripped down and at the end of each cord twirled a head, shrunken to the size of a fist, lips stitched together and wrinkled and leathery but gruesomely bright of eye, gruesomely human.

The long hair was black and coarse, and the heads were low-browed, their lips thick like a savage's. There had been a picture of just such a head in the book Turner had been reading and so he was sure that they came from the Ecuadorian jungle, that the witch-doctors of the Jivaris had shrunk them so, that—

There was a stir in the room, a vast sigh. It brought Doc's eyes down to the floor level. The men were not looking at the ceiling now. They were looking at Nanya Karista.

Where she had come from he could not tell, nor how she'd gotten to the center of that chamber so quickly without a sound reaching his ears.

Her pale lips parted. The voice that came from them was not the voice Doc had heard from her before, but toneless, almost metallic. "You have come," it said, "as you were told. That is good. And now, as you were promised, you will be shown the power that is in me."

Her hands, long-fingered, petal-like, fluttered out before her. From the floor just beneath her curled fingers a scarlet flame leaped, was blinding—was gone. Where it had been, a great cat crouched, tawny, spotted—A jaguar! Its tail lashed against its lean and hungry flanks. Its eyes, two balls of angry fire, fastened on one of the men—on Padlovich. Under its sleek hide muscles crawled and it leaped for him, bared claws reaching!

A shout of terror burst from Padlovich's throat. Then the jaguar vanished, in midair! There was nothing there, nothing at all.

Nothing but the semi-circle of squatting men and the girl.

"Like that," her strange voice intoned. "Just like that, the one you love most will be made to die if you do not make peace with the Old Ones. You think to refuse, do you not," her dead eyes moved to Padlovich, "what you have promise?"

His mouth worked, and then words spilled from them. "My boy! My Dimitri!"

"That is why the cat chose you, would have torn you, if the Old Ones had let him. The next time the cat leap, he leap for your son, and the Old Ones will let him to sink his claws—"

"No," Padlovich groaned. "No. I will pay." His gnarled hand came out of a pocket with a wad of crumpled bills and he started to get to his feet. "Here. I bring—"

"Warte—Vait!" Anstalt pulled him down. "It vass a—how you call, trick." The blonde German was on his feet. "Mit mirrors geworked. I vatch not der tiger, aber behind der voman und I see—Vait, I show you." He was striding across the room. He was reaching an eager hand to the Stygian drapes behind Nanya—

Suddenly he became limp. He crumpled, thudded to the floor, sprawled at Nanya's feet, very still.

Dead—and there had been no sound, no flash of weapon, no movement anywhere to tell what had killed him.

Doc Turner heard hoarse shouts from the terrified men saw some start to their feet. "Do not move, you fools!" Nanya's cry rose above the tumult. "If you move I cannot save any of you from the Old Ones!" There was genuine terror in her voice, genuine concern in her warning.

THE light blinked out, then was on again. Doc gasped. Giuseppe

Liano's shaking hand was pointing to the vacant place on the

floor where blond young Anstalt's stricken body had been.

"Where'sa he go?"

"Look." The girl's frail hand pointed upward, and her voice was a gasp of horror. "Look!"

Every eye turned upward. Where she pointed, a new head twirled at the end of a fibrous cord. It was shrunken to the size of a fist like the others. Its lips were sewed together with fibre like the others. But it was white-skinned, and the hair was blonde!

His skin an icy sheath for his body, Doc Turner was incapable of movement. The Jivaris are said to take weeks, months, to shrink the heads of their victims to miniature size, but Kurt had died only five pounding heart-beats ago!

And then the black wall-drapes parted revealing an open doorway. A white man crouched in it, black-bearded, mouth distorted by a grin of awful triumph, and behind the white man crouched a kinky-haired, black-faced savage in a jungle panoply of feathers and paint.

The Jivari held a long tube in his hand, a tube all of nine feet long. Doc started down to the cellar. He'd seen enough, too much. He'd seen murder done and he must fetch the police before the killers escaped—

He froze at the foot of the stairs. Somewhere he heard a snuffle, and now there was a low growl and the pad, pad, pad of an animal's paws, coming toward him. Of a dog's paws! It was the huge mastiff. The beast bounded out of the blackness toward him.

Something flashed from Doc's hand. There was the sound of thin, breaking glass on the floor. The hound snarled at it, leaped. The old druggist dropped under the arc of the dark body and rolled as he heard it thud against the stairs.

Something flicked past him, struck inches from him. A long, slim black tube jutted out into the dim green radiance from within the cellar shadows. A bronzed, half-naked figure, machete in hand, sped toward him. The kink-haired Jivari was incredibly swift, but the glass thing the druggist threw was swifter. It broke on the painted, brown face and the savage reeled, clawed at its eyes.

Doc was up out of the cellar and out in the fog of Potato Alley again, and behind him there was a shrill yell of pain. "They'll get away," he murmured. "The real criminals will get away," And then he butted into an unseen form, felt his right arm clutched by bruising, merciless fingers.

"Got yuh," his captor grunted.

Breath whistled out of the old man, and he groaned. He'd not reckoned on a guard outside here. He could not get at the last of the ampules, the thin-walled glass containers of amyl-nitrite he'd put in his pocket to use against the dog that he was certain he'd run across. "Yes," he admitted. "You've got me."

"Doc!" Jack Ransom's voice exclaimed. "By all that's Holy, it's Doc you've got there!" Turner saw that there were other shadowy forms about him. "Doc. I had a hunch this was where you were headed for, and I was just on my way here, when these cops showed up in a squad car. Someone had heard a scream, like somebody was being killed, and they phoned the cops.

"Somebody was killed," the old pharmacist snapped, "and the murderers are still in there. Surround the place—"

"Surround, hell," one of the policemen grunted. "We'll go in and take 'em."

"No. No, not yet," Doc exclaimed. "Don't go in there until Jack runs down to the fire house and gets some rubber coats for you, and some smoke masks."

"Masks! Holy thundering—! What do we need masks for? And rubber coats? They won't stop bullets."

"No. But they will stop something more dangerous than bullets in the hands of a Jivari. A curare-tipped dart, sped from a blowgun, will kill if it scratches you anywhere. Hurry, Jack. Get those things."

"He's gone," the policeman said. "He didn't wait to hear why you needed them."

THE morning sun was streaming through the windows of Doc

Turner's drug store. "So you were right about the gal, Doc," Jack

Ransom said. "She thought she had a kind of magic, or something,

through which all kinds of fierce beasts could be made to appear.

And she wanted to die, because of the way that guy was using what

she thought was her power. What was his name, that bearded

guy?"

"He called himself Niyassah when he was on the stage, but no one knows what his real name is." Turner looked very tired, but he looked happy too. "He had an act of combined hypnotism and magic, and he was very clever at it. Nanya was his helper and his best subject, and he discovered that she was most convincing to the audience if she was convinced that his illusions were actually super-natural. So he implanted the post-hypnotic suggestion on her mind that they were, and from then on she lived in fascinated terror of him.

"He'd picked up a couple of Jivaris on a South American tour, used them as dressing for his stage act. Then vaudeville died and he could only get a booking once in a while. He conceived the idea of using his genius at constructing his magical illusions, the Jivaris, and Nanya, as a means of terrifying superstitious people and mulcting them. Anstalt was right, of course, when he said that the jaguar illusion was done with mirrors. The wildcat actually performed its leap in the other room. The blonde head was just one that Niyassah had prepared, white heads with different colored hair. Poor Kurt was killed by a dart from a blowgun poked through those black curtains, and dragged out in the instant the lights were extinguished. That throbbing green light was merely a fluorescent tube into which varying electric current was fed."

"Yeah, Doc. I know all that. But what gets me, is why you still stick to it that Nanya is a nice, innocent kid. I thought you couldn't hypnotize anyone to do what's against their—their moral sense."

"That is absolutely correct, son. But Nanya was doing nothing that conflicted with her conscience. She was absolutely convinced that Niyassah had somehow learned from the Jivari witch-doctors how to use the power of what he called the Old Ones through her as a sort of medium, and she thought that she was saving his victims from some terrible doom by persuading them to make monetary sacrifices to those shadowy and evil powers. And though to commit suicide was against her religion, she wanted to die because she felt that if she did, the Old Ones would no longer have any living human being through whom to work."

"I get it. And Niyassah knew this, and he had that dog trained to follow her about and keep her from getting into an—an accident. Say! How is it the hound wasn't in the cellar when you went in? And how did he appear and disappear like he did, Doc, out here yesterday?"

Andrew Turner tugged reflectively at his white mustache. "Perhaps I was right when I said that the mastiff ran away while everyone's attention was directed to the girl. Or perhaps—Well, Jack. I told you I have been reading the account of an expedition among the Jivari witch-doctors. They were hard-headed, skeptical scientists who made that expedition. Men with not a drop of superstition in them, and yet, my boy, they report that they saw some things happen, in that steamy, primordial jungle, that all their science cannot explain."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.