RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

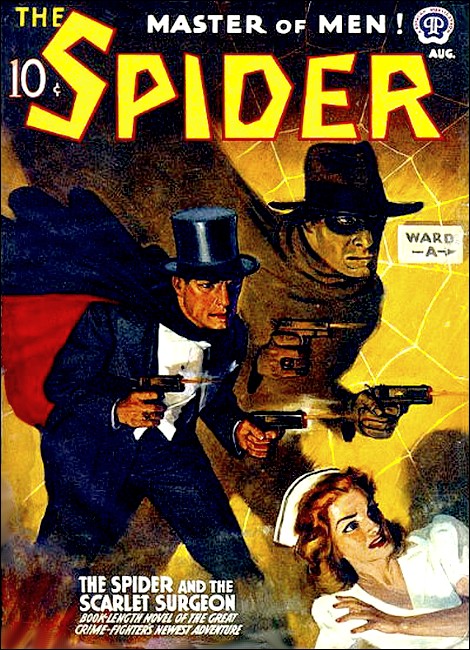

The Spider, August 1941, with "Doc Turner's Flaming Coffin"

Strange, that the little gray druggist, Doc Turner, should stand silent while his young partner, Jack Ransom, was framed into jail on a charge which must blacken his name forever... But on that night of flaming terror, the safety of Doc's Morris Street "children" meant more to him than either his own life, or that of his best friend!

EMERGING from the ancient drugstore into Morris Street's murmurous midnight, they were an oddly contrasted pair. Jack Ransom's hat-less thatch was the precise, vivid shade of fresh carrots, his countenance broadly moulded. His gray eyes crinkled at their corners with easy good humor and his smile matched the expression of his eyes.

Andrew Turner, locking up the pharmacy where most of his life had been spent, was a little old man stooped with weariness. His bushy, untrimmed mustache and the silken strands that straggled sparsely from under his battered hat were silvery, his narrow, ascetic face deeply wrinkled.

He removed the key from the lock, looked affectionately up at Jack. "That's that," he sighed. "Now all I have to do is deliver this prescription around on Hogbund Lane," his gnarled hand displayed a neatly wrapped small powder box, "and one more day will be ended."

The crescendo pound and crash of an EL train on the trestle overhead drowned the end of his sentence. Yellow oblongs of light from its windows skimmed the cracked, debris-strewn sidewalk along which the old druggist and his young friend moved towards the corner.

The train roared off. "You go on home and get your beauty sleep, Doc," Jack said. "I'll take care of that package for you."

"Will you, son?" Turner's tired voice was grateful. "The very thought of climbing four flights of stairs is appalling."

"Hand it over, Doc."

A moment later, Jack strode down the desolate side-street, lithe and quick and purposeful. Doc remained motionless, a shabby, frail figure peering after him.

Just what held the old man there, himself he was not fully aware. Some vague apprehension stirred within him. Something had touched the intuition Doc Turner had learned not to ignore, gained from his long years of battling the mean and dangerous criminals who prey on the helpless and bewildered aliens of Morris Street, whom he'd served longer than he cared to recall.

There seemed no justification for his uneasiness. Hogbund Lane was exactly as he'd seen it thousands of times at this hour, a brooding and lonely gut whose borders were serrated by long rows of stoops up one of which Jack Ransom was now climbing.

Empty now, it was still redolent of the lush life with which it had teemed all day and all evening, swarms that slumbered now behind the drab tenement facades walling it in. Feebly illumined by wide-spaced street lights, it was silent as some moon-bathed canyon in the Badlands that in a queer, distorted way it resembled.

The dark vestibule swallowed Jack. Heavy footfalls thudded, down there at the end of the block. A burly, blue-uniformed shape came around into Hogbund Lane from Pleasant Avenue, plodded towards Morris Street along the opposite sidewalk.

The policeman's stolid, matter-of-fact progress, the nonchalant twirling of his nightstick, dissipated the eeriness of the night. Doc's lips twisted in a wry smile and he turned to resume his interrupted homeward journey.

A muffled shout swung him around again. It was pierced, drowned out, by a high-pitched scream of rage—or feminine terror.

The policeman lurched into a run that angled across the gutter—straight for the house into which Jack Ransom had gone! Doc Turner too was running but he had farther to go. By the time he reached the rickety front steps the officer had already disappeared inside.

Behind Doc windows screeched open and startled voices called questions. The vestibule tile was gritty under his feet. A tiny hall-light was bright enough to define only vaguely a rickety, linoleum-covered staircase on which the cop's feet pounded. Above that sound, as Turner started running up the stairs, came a whining babble like a wounded animal, and an unintelligible rumble that had Jack's familiar intonations.

Turner went past cautiously opening doors on the dark first landing, up the next flight, along a lighted landing, and up another flight.

"What is this?" the cop demanded.

Blue and burly in dim light, Doc recognized the officer as Tim Mullin.

A SOBBING heap was crumpled at Mullin's feet and Jack

Ransom was staring down at it, scarlet streaking his cheek, his

pupils dilated.

"What's all this?" the cop repeated. "What's coming off here?"

"I—I don't know!" The streaks across Jack's face were bleeding scratches. "She—" As he lifted his head his eyes were dazed, incredulous. "She jumped me out of nowhere—"

"Liar!" shrilled from the heap on the floor, and a slender arm emerged from it. A pale hand clutched the staircase balustrade, pulled erect a slim girl, her black hair tumbled about her distorted countenance, the dress ripped from an olive-skinned shoulder.

"He grabbed me!" A sob choked her. She fumbled with the rags of her frock, her dusky-red lips writhing. "He grabbed me an' put his hand over my mouth, but I scratched him an' that give me a chance to jerk my head loose an' yell."

She was young, about eighteen, and pathetic in her disarray. "He whispers to me to shut up, but I keep on yellin' an' he clouts me down."

She abandoned the attempt to cover her shoulder, and put her hand to a darkening bruise on her high cheekbone. "'N then he bends an' starts to pick me up, like he's gonna carry me up to the roof maybe, but he hears you coming—"

She stopped, breathing hard, and the pause was filled with a many-voiced growl from the pallid shapes that now crowded the dim stairs above and below this landing.

"So that's it," Mullin grunted. "So that's what you were up to, you dog," and his fist drove for Ransom's jaw.

Jack caught it on an upflung elbow. "Hold it, copper. Give me a chance." The desperate ring of his entreaty stemmed a second blow. "The girl's nuts. She jumped at me out of the dark here, screaming like Satan himself was after her, and clawed my face before I knew what was what. I didn't touch her—"

"Don't touch me!" the girl shrilled. "What about this?" She pulled irate fingers across her bruise. "An' this?" The same fingers jerked at the shreds of her dress. "If you didn't, then who did?"

"Don't ask me. All I know is you were like that when I first—"

"The black-hearted scoundrel," a rough voice from somewhere in the listening crowd interrupted. "He ought to be strung up." The growl ran through again, deeper-toned, as a half-dozen threatening alien tongues merged into that terrible universal language of a lynch-mad mob.

Doc Turner went cold, but before he could move or speak Tim Mullin had heaved around to the black tide welling in that tenement hallway, was driving it back with his voice—not loud but very distinct.

"None of that stuff, you. I'm handling this, and I don't need no help."

For an instant longer he glowered into the now hushed dimness, spraddle-legged, vested with the authority and dignity of his uniform and all it represented. Then he turned back to Ransom. "You live here?"

Jack let held breath seep out between tight lips, relaxed slightly. "No, Doc Turner, the druggist on Morris Street, asked me to deliver a prescription to Lenero, up on the top—"

"He's a lie!" Mountainous in a dingy bathrobe, a pillow-breasted woman leaned over the rail above. "He no bringa me no med'cine. I got nobod' sick in my house."

Doc's brows knitted. He started forward—halted abruptly and shrank back into screening shadow as Jack exclaimed, "Sure you have. Here's the prescrip—" He broke off, staring at the hand he'd lifted to show the wrapped package. The hand was empty!

"What—I must have dropped it." He looked down at the floor. "It isn't—Someone must have picked it up." He peered into the inimical faces ringing him, and panic came swiftly into his own face, into his voice. "Who's got it?"

There was no answer; only the sound of hard breathing. "Cut the comedy." Mullin's huge, spatulate fingers sank into Jack's upper arm. "There wasn't no prescription, and the rest of your yarn's as phoney as that. Come along, you."

"But—"

"But, nothing! I've heard enough out of you." The officer looked around at the girl. "Look, you—What's your name?"

"Rosa—Rosa Garcia." The vindictiveness was out of her voice, she sounded puzzled, oddly uncertain. "Listen, copper I—I'm all right now. Maybe—maybe we can call this off..."

"No we can't! You needn't be afraid of this bozo. Where he's going to be the next couple years, you'll be safe from him. Now, look: There ain't no use your going along to the precinct tonight. I'll put the complaint in for you and I'll let you know in the morning where to come. Where'll I find you?"

"Right here. I room with Mrs. Rosenblum on this floor, the rear flat. I was out to a party an' I was just comin' home—"

"Okay. You go get yourself some sleep so's you'll be able to talk straight to the magistrate in the morning... Break it up, the rest of you. Break it up! That's all there is, there isn't any more."

The crowd disintegrated into excitedly chattering knots as Officer Mullin started down the stairs with his white-faced prisoner. Far worse than any punishment the courts might impose on Jack Ransom were the black looks that followed him, the black disgrace with which he'd be indelibly stamped, unless he could be proven innocent of the despicable crime of which he stood accused.

THE one man who could have at least vouched for his right

to be in this house, a man whom he almost looked upon as a

father, and whose speaking up for Jack would have gone far to

break the frame in which he was caught, oddly kept silent... No

one noticed the little gray pharmacist as he slipped down the

stairs and hid in the blackness under the slant of the lowermost

flight.

The tenement took a long time settling back to slumber. Voices gabbled in the halls. A baby cried, fretfully, and the smell of garbage came up to Doc from the cellar. Cooking smells of foods long ago consumed, of clothes mouldering with age and sweat, and of humans mouldering with poverty and disease, were foul in his nostrils.

Andrew Turner thought back to the bearded physician who'd left the Lenero prescription with him to fill, well after eleven—Doctor Vittorio.

When the old druggist had remarked that this was the first time he'd had the pleasure of meeting him, he'd explained that he was the contract doctor to an Italian Benevolent Society the Leneros had just joined. The people around here had many of these organizations that provided medical attention to their members. New ones were cropping up all the time, and so Doc had accepted the statement without question. The prescription was perfectly normal and legal.

The talk on the stairs, the shutting of doors, dwindled and ceased. He began to be conscious of the far-off roar of the city's nocturnal traffic as the nearer noises ended. A tread creaked, right over him. Light feet whispered stealthily down the stairs.

Doc poked his head out just far enough to bring into view the fastened-back vestibule door that had invited Jack to enter without ringing the Leneros' bell.

A coated, slender figure came into its frame, crossed to the outer threshold, stopped there and cautiously scanned the street. The parsimonious overhead bulb sent its feeble, grimy light between a turned-up coat collar and the pulled down brim of a flat felt hat, found a black tendril of hair, a bluish bruise on an olive-skinned, high cheekbone.

The thin, tired lips under Turner's bushy mustache curved in a smile of grim triumph.

Rosa Garcia hunched narrow shoulders as if nerving herself to some dread task, and started down the stoop. Doc counted ten and then darted from his covert to the vestibule's outer doorway, peered out exactly as she had.

Hogbund Lane was still desolate, deserted, except for the girl, who kept as much as she could in the shadows as she went swiftly, silently, toward Pleasant Avenue.

As swiftly, as silently, Doc Turner trailed her, across Pleasant Avenue, down the long block that sloped downward to the River...

ALONG the River stand the warehouses through which flows the

commerce of the Seven Seas. Now that the nations are occupied

more with destruction than with trade, many of these warehouses

stand empty and disused, their looming dark bulks unpeopled even

by watchmen.

One such structure, smaller and more ancient than most, was dark and vacant only to outward appearance. Its steel-shuttered windows enclosed the yellow light of a lantern hung from a grimy pillar in a low-ceilinged room. Its thick walls prisoned the thud, thump, thud, thump of a busy machine.

The naked back of a huge Negro glistened with sweat as it rose and fell, rose and fell, with the spinning of the flywheel whose crank his brown hand fisted. The impression that he was less human than a part of the machine was heightened by the fact that its steel maw opened and closed in exact synchrony with the rise and fall of his torso.

That gigantic metal mouth, wet with black saliva, alternately clamped on and released oblong sheets of paper that were laid within it and snatched away by a hunchbacked, hook-nosed gnome who crouched before it. Men and machine were welded into a unit by the furious rhythm of their task, so that the pulsing shadow blotching the yellow pool of light on the floor seemed to be the shadow of some single, prehistoric beast, gigantic and evil.

As the Negro's head lifted, the lantern's rays flashed from white teeth grinning with effort, but beneath his beetling brows there were only two gruesome, empty pits. The gnome's head turned to the dwindling pile of sheets on his right, to the bed of the press, to the growing pile of sheets on his left. His thick lips, his blank face and his eyes empty of all expression, left no doubt that this deformed being was less than human; less, even, in intelligence, than an animal...

The printing press, symbol and instrument of Man's triumph over Nature, was served in this hidden place by a blind man and an imbecile, and so had become a perfect symbol of the Machine's triumph over Man.

Somewhere in the blackness beyond this macabre group, a blacker shape moved. It neared, emerged into the light—a tall, spare individual whose swarthy, sardonic countenance was given an Oriental cast by a raven beard, curly and long and square-cut at its corners.

His eyes, black, glittering knife-points, went to the pile of finished papers. Long, sensitive fingers reached out, plucked up one of them. Only by a slightly swiftening tempo of their work did the slaves of the press betray their awareness of his advent as he read what they had printed.

The sheet was a large one. Blocked off in squares, the matter on it was in different shapes of type, in different languages—Polish, Italian, Yiddish, Greek.

The English text, bold letters in the fashion of screaming headlines, centered it...

The bearded man's nostrils pinched as he stiffened suddenly, turned to some sound he'd heard below the rhythmic thud, thump, thud, thump of the press.

Within the darkness out of which he'd come a vertical yellow line blossomed, widened till it was a doorway illumining long rows of gray wooden pillars like that from which the lantern hung. Silhouetted within the frame of the jamb was a girl's slim, coated figure.

The bearded man crumpled the paper in his hands, and hurried to his evidently unexpected and alarming visitor.

Rosa Garcia retreated before him, hand caught up to heaving breast in a gesture of fear.

He pulled the door shut, behind him. "What are you doing here?"

"I had to come, Rustom. I had to tell you—. I worked it the way you said, but he sent someone else with the medicine..." Her voice trailed away.

Rustom hadn't moved, hadn't changed expression, but his black wrath seemed to fill the little office. It was bare-floored but furnished with a desk and chairs.

Its one window was steel-shuttered. In the wall right-angling that through which he'd entered was another, paint-peeled, warped a little in its frame. A green-shaded electric bulb hung from the ceiling by a cord crusted with dirt, but the light here came from another lantern perched on the old and scarred desk.

Rosa hesitated. "It was dark," she said. "I couldn't see that it was a young man till I'd already jumped at him, and then I had to go through with the play. I didn't know what else to do."

Rustom put the circular on the desk. "You said he sent this young man." He carefully smoothed the paper, as though this were his greatest concern. "How do you know that?"

"He had the package. I snatched it from him as I threw myself to the floor, shoved it into the breast of my dress. A policeman came, but I got rid of the little box and its contents afterwards, while I was dressing to come here. He—. He was good-looking, Rustom. He had red hair—"

"Ahhh! That would be the garage mechanic who assists the old man in his meddling. I have been warned against him also, but he is dangerous only as long as Turner does his thinking for him. Let me see..." He started pacing the floor. "There must still be a way that I can tie the druggist to this affair."

"The Lenero woman has already announced she ordered no medicine." In the brighter glare of the lantern, Rosa no longer appeared the eighteen year-old girl she'd seemed in the dimness of the tenement hallway. Her body was still slim and shapely but taut cords ridged her neck, the skin in the hollows between them finely wrinkled, and in her eyes was ageless knowledge of evil.

"Maybe we can—" Rustom hurled himself to the second door, flung it open and was through it!

Fists thudded on flesh in the darkness outside. Rosa's mouth opened in a soundless scream. Rustom reappeared; over his shoulder was slung the body of Doc Turner. He pulled the door shut with his free hand, fixed the woman with his glittering eyes.

"You made two mistakes, my dear wife. Not only did you catch the wrong man in my carefully laid snare, but you permitted the right one to trail you here. However," he smiled, menacingly, as he slid the old druggist down into the swivel chair behind the desk, "the two errors, as sometimes happens, cancel one another. Andrew Turner will not interfere with me tomorrow—nor with anyone else, ever again."

"No!" the woman moaned, gathering his meaning. "You haven't killed him?"

Rustom straightened. "Not yet. But now that you've led him here, there is nothing else I can do."

THROUGH the hammering pain in his head, Doc Turner heard

this calm pronouncement and recognized the voice as that of the

man who, not many hours before, had called himself Doctor

Vittorio.

Doc was not stunned; he had pretended to be as the only way out of a struggle he could not have hoped to win. When Rosa had unlocked the battered door in the wall of the apparently disused warehouse, Doc had chuckled to himself at this proof of his wisdom in following her. The lock had been easy to pick, his gnarled fingers as skilled at this unusual task as at rolling pills. He'd found himself in a tiny foyer, crouching at the inner door to listen. Here he'd made some small sound that had brought the bearded man hurtling out upon him.

"You're going to—?" The sentence caught in Rosa's throat, broke through. "You can't murder him, Rustom!"

"Why so finicky, my dear? A quick, clean death, rather than dragging out his few remaining years in prison, or worse than disgraced in the eyes of those who respected and loved him..."

The man was neither arguing with himself nor justifying himself to the woman. The sneer, the hint of taunting mockery, in his voice showed that he was merely drawing for her a picture of what she was, stripping her beforehand of any ascendancy she might gain over him by knowledge that he was a murderer.

But it wasn't conscience that troubled her. "I don't care about that. It's what they'll do to you when they find him... The punishment for murder is the electric chair—"

"They won't find him."

Lolling in the chair, Doc very slowly let his eyes slit open.

He could see only the top of a desk, the base of the lantern whose hot fumes were acrid in his nostrils, a paper that had been crumpled and smoothed out, the fresh ink smeared.

The sheet was printed in many languages, but square in its center was the English version:

JOBS! BIG PAY!!! JOBS!

$15 A DAY $15

SIX-DAY WEEK

Thousands of men are wanted to earn

Ninety Dollars a Week in making a

SECRET DEFENSE WEAPON

This big pay is offered because the

location of the factory and what it

is must be kept secret,

so workers

will not be permitted to leave or

write to

friends till job is completed.

NO SKILL REQUIRED

If you want to earn this big money and

fight

the Dictators at the same time, you must

HURRY! HURRY! HURRY!!!

Six Months Work Guaranteed

Today only from 8 to 10 P.M.

at

216

Water Street.

Be ready to leave for Secret Factory.

Bring clothes and Twenty Dollars

deposit on Fare and Board

which will

be refunded with your first

NINETY DOLLARS PAY

any part of which you can arrange

to have

sent to your family.

TODAY—8 to 10 P.M.—TODAY ONLY!!!

Rustom grunted, "Listen, Rosa. In that pile of old crates

at the back of the loft is a big one filled with straw. Get Jed

to bring it in here. Not Martin, remember. Even his idiot brain

might wonder what had become of the old man if he sees him

here."

Doc heard a tremulous sigh, light feet move on a bare floor. A door opened and the thud, thump, thud, thump of a machine came to him. Then the door closed again, and there was no sound at all.

"How do you like my little circular?" Rustom asked.

Turner opened his eyes fully, straightened up in the chair. "Very interesting. Tomorrow is payday in the factories where the immigrants of Morris Street work, and when they come home with their wages, your ninety a week will seem like a promise of the heaven to them. Many of them will fall for it."

"At least a thousand, I figure, which would give me twenty thousand dollars." The bearded man was fondling a two-foot length of lead pipe in his hands. "My expenses have amounted to about a hundred dollars. A good investment, don't you think?"

"And a safe one," Doc agreed, as calmly as if he were discussing the purchase of some securities in Wall Street, "provided you could make sure that I would not interfere. Your only difficulty was the habit the aliens of this neighborhood, unacquainted with the strange ways of this strange land, have of coming to me for advice on any proposition like this. You knew I would spot the palpable fraud at once, and so you had to destroy their faith in me."

"Precisely."

Doc Turner smiled wearily. "And when your attempt to do that failed, I obliged by walking straight into your trap. You intend to crush in my skull with that pipe, nail me up in the crate of which you spoke, and have your man Jed carry me across to the River, where the ebb tide will take me far out to sea by morning. Before you do that, though, I am curious to know how you expect to escape from that crowd of men, after pocketing their deposits. They are not quite credulous enough to let you get out of their sight before they actually start on their way to this mysterious factory."

Rustom stroked his beard, in his eyes a hidden admiration for the old druggist. "They'll pay me their deposits in here, then they'll be sent through that door to wait for the buses." Doc saw now that the door through which Rosa had gone was a heavy one of metal, originally built so to comply with the city's fire laws. "I've riveted shut the steel shutters over the windows in there, and the big doors through which the trucks used to drive with their loads, and provided for an impregnable fastening for this one."

Three arm-thick iron bars leaned beside the sturdy jamb, ready to be dropped into heavy sockets bolted to it.

"The walls are so thick nothing can be heard through them. Even if some of their women come with the men to see them off, I shall have sent them home, and no one, of course will expect to hear from my dupes. Perhaps they will eventually break out of there, perhaps not; but by the time they can possibly do so I shall be beyond fear of pursuit."

Black anger surged up into Doc's brain at the sheer brutality of the scheme, but anything he might have said was checked by the movement of the steel door. Rustom's arm swept up, the wrench clubbed in his fist.

It hung motionless, a voiceless threat that a sound from the old man would bring it crashing down on him, whatever might be the effect on the blind Negro giant who trundled in a big wooden case as effortlessly as if it had no weight at all.

"Put it down there," Rustom directed, and the girl guided the box down to the floor beside the desk. Its wood was gray with age, the straw that spilled from it musty-smelling.

Rosa took the black arm to guide Jed out, when a scream, high-pitched and rattling and horrible, squawled from Doc's throat. It swung the big Negro around in a reflex terror that brought him blundering against Rustom.

Turner planted his feet against the farther wall of the desk's kneehole, and shoved. It was enough to force the desk against the shins of the bearded man, who was thrusting Jed out of the way of his arm's lethal downswing.

That gave Doc the split second he needed to hurl the lantern into the straw-filled crate, and he dropped down beneath the protection of the desk-top. The crash of glass and an incoherent, fury-filled shout from the bearded man mingled with the blind one's jabber and Rosa's scream. And Doc managed to slide around the corner of the crate and get to the doorway into the loft.

Flame spurted out of the box that had been meant for his coffin, a hissing tall tongue of scarlet fed by spilled oil and dry straw.

Turner lifted, clawed at the steel door. It clanged into its frame just in time to receive the impact of the lead pipe Rustom hurled, but there was no lock on this side, nothing with which it could be fastened.

Doc whipped around, searching the darkness for some niche that might offer him safety, and saw only the lantern-lit printing press. Its gnome-like attendant, imbecile jaw lolling, scuttled toward him. The deformed body, the long reaching arms, were bestial, and there was a bestial ferocity in the feline spring of their owner.

The door-knob, on which the old druggist's hand had frozen, rattled, and then was pulled from his grasp. Crimson firelight struck through as he leaped away, running off to the side to evade the oncoming dash of the idiot gnome. The dark room was filled with the wavering ruby glare of the fire, with its crackle and hiss and Rustom's shout, "After him, Martin! Grab him!"

Glancing behind, past a wooden pillar, Doc saw the tall man plunge through the doorway, smoke belching after him, red sparks in his macabre beard.

Now Doc had only the gnome to evade. He did so by sprinting past him. This sent him to the back of the loft, however, and put Martin between him and the only exit from it. Too, Rustom had joined the chase now—not only Rustom but the woman! But Rosa was running straight across the floor towards the printing press. She reached it, grabbed up a stack of the bulletins from the bracketed shelf, and was running back to the fire-filled office doorway.

Doc reached a mound of old barrels and boxes at the rear of the loft. Rustom was still far back in the chase, but the hunchback was only ten feet behind.

Doc Turner snatched at a barrel, threw it on its side and sent it rolling. The moron slammed into it, screeching.

Doc was climbing the high pile of discarded containers, squeezing in between its top and the loft's ceiling, and fighting for breath with tortured lungs.

A box slid from under him, then another. Suddenly the whole pile was toppling, throwing him back towards the oncoming Ruston. He lunged forward, his feet higher than his head.

Somewhere, muffled by distance, a voice shouted, "Fire! Fire!"

Gigantic against fire glare, Rustom scrambled to get to him, his hand clutching once more the lead pipe. "No!" Rosa's scream came. And from somewhere, backgrounding that shrillness, was a clangor of bells. A rush of water and a hiss of steam, and the fire-glare was dying.

"The firemen are here. If you kill him now we'll all die in the chair!" Rosa's voice rose. She was scrambling to Rustom, grabbing his arm.

She wrenched his lead weapon from his fingers as a deep voice bellowed, "Hallo—Hallo in there. You can't get out that way but we've got the fire licked. You're all right now."

"All right," Doc Turner muttered, and let the black wash of almost unendurable fatigue well up into his brain.

LATER Doc Turner explained, "Jed, the blind Negro,

blundered through the outer door, somehow, and into the street. A

watchman in one of the other warehouses heard his shouts and sent

in the alarm. Rosa had thrown all the circulars into the fire,

but she forgot that the type in the press could be read. That

substantiated my story, and the district attorney has assured me

that they'll go up for long terms. Jed and Martin had no part in

their scheme, of course, and are being held only as material

witnesses."

Red-eyed for want of sleep, Jack Ransom said softly, "You sure had a tough time of it last night."

"Not as bad a time of it as you did, son, with that damnable charge hanging over you. I almost came to your rescue there in that tenement hall, but Rosita Lenero's denying that anyone in her family was ill made it clear that you'd stepped into a trap laid for me. It was I whom the fake Doctor Vittorio had expected to deliver the prescription he'd left with me—purposely so late that I wouldn't be able to get a boy to do it for me. It was I whom the girl was to have accused of attacking her. I figured that the only reason for that elaborate set-up was to remove me as a threat to some plot brewing against my people. I had to find out what it was.

"The girl, obviously, was taken aback at discovering she'd embroiled the wrong man, and had to continue her act. Almost certainly she would try to reach whomever was behind it, to ask instructions as to what to do about appearing against you in court. If I had gotten you out of that mess, I would have put her on her guard and lost my chance to unearth what was going on. Nevertheless, it was a damnable thing to do to you. I..." There was a suspicion of moisture in the faded blue eyes. "Can you forgive me, son?"

"Forgive you?" Jack stared at the white-haired old man, muscles knotting his blunt jaw. "No! I can't forgive you for ducking out on me and not figuring out a way to get me in on that scrap! I'm supposed to be tough guy in this combination, you know—not you. You're just supposed to have the brains."

"Brains," Andrew Turner sighed, "would have been of very little use to me in that straw-filled coffin, floating out to sea."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.