RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

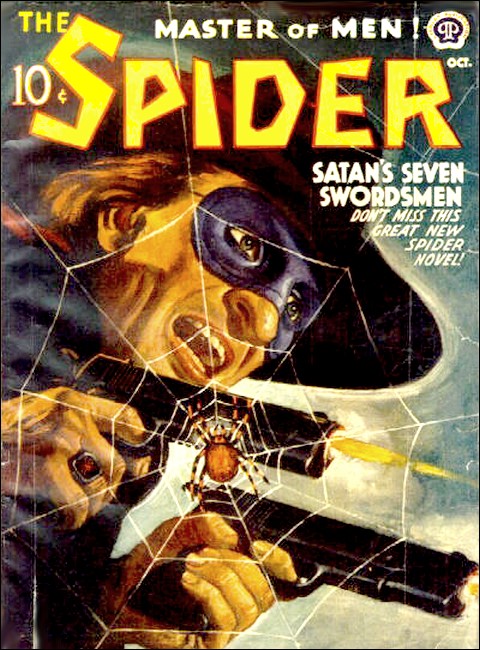

The Spider, October 1941, with "Bargain Counter Corpse"

Tracy's Department Store boasted it could undersell all competitors on every item—but that didn't include the corpse of the young working girl Doc Turner thought to be the keystone of a novel and horrible racket!

ANDREW TURNER awoke all at once, as an old man does, to find

that his dream had become a nightmare of reality.

The desolate landscape of his dream was now the lodging house bedroom that for so many years had been to him, not home, but the place where he spent the few midnight-to-morning hours away from his ancient drugstore on Morris Street. His dream's eerie, shadowless light was now a grimy dawn seeping in to give the shabby, scant furniture oddly menacing outlines. And, impossibly gigantic in the gray luminescence, a faceless form loomed blackly over him.

Only one thing was sharp and distinct and unquestionably real—the steely glitter of the knife-blade that had pricked his throat and now hung above it, poised.

Outside the open window was the nocturnal growl of the unsleeping city, the rattle of an "El" train, a sick infant's petulant whine—and the rasp of the radio in a police prowl car, just below! But Doc Turner knew that the instant he opened his mouth to cry for help, silencing steel would slice down.

His white-haired head lay very still on its pillow, but the tobacco-stained bush of his mustache moved with a faint smile. "The pose," he said gently, "is, I confess, frightening. But what are you after?"

The intruder stirred. "What did Jennie Marshall tell you last night," the black mask whispered, "in the back of your store?"

"Nothing concerning anyone but herself." This was the exact truth. "And her young man. He is being inducted into the army day after tomorrow, and she wanted me to persuade him to marry her before he goes. But I pointed out that unless he loved her enough to marry her without persuasion, it would be wiser to wait till he comes back and see how they both feel then."

"You 'phoned someone, and she got in the booth with you. Who was it?"

Doc's faded blue eyes narrowed, but in his long years of battling the human wolves who prey on the bewildered aliens and helpless, friendless poor of the slum he served, he'd learned not to quibble with a gun or knife. "She'd given up her job at Tracy's Department Store, sure that she was getting married, and it is already filled. They've a long waiting list. I called the home of a friend of mine to try and place Jennie with him. He liked the way she talked over the 'phone, instructed her to report for an interview early this morning."

"You lie!" The masked man crouched lower, his black garb whispering against the bed's side-rail. "Come clean, if you want to live."

There was no fear in the old man's wrinkle-netted countenance. "Live?" he murmured. "For another year or two? I wonder. At any rate, I'm too old to be afraid of dying."

The knife moved, slowly, till it hovered ominously above his blanket-covered abdomen. "The way you'll die, Turner, you'd better fear. Talk. Who'd you tell what the Marshall skirt spilled?"

"Whom," the pharmacist sighed. "Whom did—" and his right arm which Doc covertly had worked out from under the blanket-edge, circled the black-clad legs, jerked them hard as his left hand flung up the blanket to tangle the knife.

The aged muscles were feeble, but for a split-second surprise was as effective as strength. The man in the mask staggered. He recovered almost at once, but not in time to prevent Doc from leaping out the other side of the cot, or choke his incoherent yell as he grasped the door knob.

The door was locked! He snatched for the key, turned it, but the black form had vaulted the bed and hurtled at him, steel flailing.

Turner dropped under the knife's lethal arc, half-somersaulted, half-rolled from the attacker's path. "Help!" he yelled, and a shout answered. The door opened and the masked man dived into the dark corridor that suddenly was clamorous with feminine screams. A man shouting, "What the hell's going on?"

But the masked man had vanished before anyone ventured into the hall.

"It was a nightmare," Doc Turner told his fellow lodgers. "I fell out of bed and woke up shouting. It's nothing..."

THE morning sunlight, shadow-grilled by the trestle of the

"El", laid itself on the white-painted shelves and heavy-framed,

out-dated showcases of the old drugstore on Morris Street.

"I don't get you, Doc," Jack Ransom said as he scratched his thatch of carrot hair. "I don't see why you covered it up. Why didn't you call the cops?"

"What would have been gained?" Doc Turner asked the barrel-chested young garage mechanic who so often aided him in his unofficial, but exceedingly effective war on crime. "Except to terrify the people who live in that house? I couldn't describe the fellow. Even his voice was disguised. I could not identify him if at this very moment he were to walk in through that door."

He looked broodingly out into the hurly-burly of the slum's principal thoroughfare. Trucks rumbled in the asphalted gutter. Hucksters stripped tarpaulins from the pushcarts aligned at the curb, exposing rosy apples, green-framed, creamy cauliflower, vividly yellow stands of bananas and tangerines. The laborers and factory hands had already gone to their daily toil; now at eight-thirty the white-collar workers, stenographers and errand boys hastened along the cracked sidewalk.

"Look at those girls," Doc exclaimed. "Heads high, eyes bright, smartly dressed as any Garden Avenue debutante at a cost per year that wouldn't keep a socialite in perfume for a week. Aren't they grand youngsters, Jack?"

"Yeah," Jack grunted. "They're all right, but what's the idea changing the subject?"

"I'm not, son. I have a sneaking suspicion that what happened to me last night very directly concerns those fine young people."

"Huh? Oh, I get it. This Jennie Marshall—"

"Is one of them. A lovely child, about eighteen, pretty as a picture and smart as a whip. But she's an orphan just about getting along, in a furnished room she shares with two other girls. I cannot imagine why anyone should threaten murder to find out what she had to say to me, unless," the old man put a blue-veined, transparent-skinned hand on Ransom's sleeve, "unless this is another instance of the sort of thing we've been up against time and time again."

A muscle twitched in the youth's freckle-dusted cheek. "You mean he figured she'd spilled the dope to you on some racket that's working a whole bunch like her? Some racket designed to nick a little bit from each one of the thousands of them?"

"Yes—and a racket which he thought I'd already started machinery to crush," Doc murmured. "Precisely. Which means we—" A 'phone bell shrilled from the booth behind him.

When he came out of the booth, a half minute later, his eyes were oddly expressionless. "Jack," he said softly. "That was the specialty-shop proprietor with whom Jennie Marshall had an appointment at eight this morning. He 'phoned to tell me that she hadn't arrived yet and that if she couldn't be punctual, he couldn't employ her even as a favor to me."

"So she let you down, eh? Well it just goes to show—"

"I want to know what it goes to show," the old druggist interrupted. "Here's her address." He brought a slip of paper out of the pocket of his threadbare alpaca coat. "Five-twenty Hogbund Lane. Please go there and find out why Jennie didn't keep her appointment."

What Jack Ransom found out, when he'd climbed three flights of malodorous tenement stairs and interviewed the slattern woman who rented furnished rooms at two dollars a week, three in a room, was that Jennie Marshall had never come home last night.

"You might ask Ben Cartin," she smirked, "he's her boy friend." She told Jack where Ben worked, as shipping clerk.

But Ben Cartin, a sallow and pimply-faced shipping clerk, swore that he had not seen her since she had left him in a huff, yesterday evening, and he proved it.

Nor could anyone else be found who had seen the girl after she left Doc Turner's drugstore on Morris Street. No one at all.

THE One Day Sale of Thirty-Dollar rayon sport ensembles, three

pieces for six ninety-seven, was the most successful promotion

Miss Jameson ever put over. From the minute Tracy's opened, the

fifth floor was a riot. By eleven it was a seething sea of

excited customers.

But no bargain rush could for long vanquish Miss Jameson's sense of order. When she noticed, around four in the afternoon, a blond dummy leaning against a pillar, she dropped everything to go over and straighten it herself.

She grabbed hold of its dangling arms—and screamed!

That scream struck the fifth floor dumb, motionless for a half-minute. The cartwheel hat dropped from the dummy's blond curls, revealed its pert-featured, small face. "My Gawd!" some salesgirl said, not loud but very audibly in that awful hush. "It's Jennie Marshall!"

It was the corpse of Jennie Marshall, fastened to that pillar by almost invisible wire, and—"Look," the same girl said, her tone still flat with a horror too terrible quite to be realized yet. "Her lips are taped together."

And then, in the split-second before pandemonium broke, a raucous voice shouted from nowhere. "It's the squealer's sign. She talked too much."

In that screaming, fainting, fighting mob of women, who could spot the man who shouted that?

THE finding of Jennie Marshall was not known to Morris Street

till the girls and the young men who worked at Tracy's (there

were many in the neighborhood) returned to it, very late because

of the long and wholly futile police interrogation.

The murder of an unemployed salesgirl, even by the rather unusual method of asphyxiation with ether, did not warrant special radio bulletins, and the injury of a number of stampeding shoppers was a matter that Tracy's had relegated to the back pages of the newspapers.

Those of Jennie's ex-co-workers who dropped into Doc's on their way home answered his questions in monosyllables if at all, and left in almost discourteous haste. "They're frightened," he told Jack Ransom when the carrot-headed youth showed up. "They're almost too terrified to think, much less talk about it. Which, of course, must have been the reason for that grisly demonstration."

The hoarse shouts of the peddlers came in from outside, the shuffle of the slow moving throng that crowded Morris Street in the glare of the huge bulbs strung over the pushcarts, a jabber of talk in a dozen foreign tongues. "How the hell," Jack groaned, "did they ever get the corpse set up without being caught?"

"Easily enough, son. That gigantic department store has hundreds of employees who know only those in their own departments. Do you think anyone would recognize as an impostor a porter in the regular store uniform, swapping a body for a dummy in the crush of that bargain sale? He probably used one of those big crates-on-wheels they're continually pushing through the aisles."

"Yeah, I guess you're right. It was easy enough for anyone who had the nerve."

"And the imagination, son," Doc Turner added, his gnarled fingers beating a tattoo on a showcase edge. "The strange, twisted imagination that also suggested covering the whole face of the man who invaded my room with a featureless mask. The macabre imagination that etched the blade of his knife with a mouse in the jaws of a cat. We're up against a ruthless criminal, my boy."

Knotting small muscles ridged Jack's blunt jaw. "Yeah. I see what you mean. Look, Doc. You've still got that knife, haven't you?"

"Yes. But it is an ordinary hunting knife such as may be bought in any hardware store. Its only distinguishing mark is that etching, and that was done by the owner. I'm afraid it cannot help us—yet."

His eyes sullen, Jack gazed out at the shawled housewives, the hundreds of swarthy and pallid faces that moved past the doorway. "I've got a hunch one of them's out there somewhere, watching you. They know you're trying to stop them, whatever racket they've got, and they're snickering up their sleeves because they know you haven't a chance to."

"That's the handicap of having a reputation." Old Doc Turner smiled wanly. "And one more proof that their leader is no ordinary criminal. He knew that anyone who has attempted to prey on my people has found he had me to deal with, and so he had me watched right from the start."

"Which was poor Jennie's hard luck," Jack agreed soberly. "It looks like he's got us stymied, Doc. After what happened to her, it will be a miracle if we even find out what it's all about when it's all over."

"I shall find that out, Jack, and stop it." The nostrils of Doc's big nose flared. "I think you mentioned," he murmured, "that Mary and Helen, the two girls with whom Jennie roomed, also worked at Tracy's in the same department."

The youth turned, his face graying. "Gosh, Doc! Don't you think those birds are smart enough to figure you'll try to pump those two kids? What do you want to do, have them bumped off too?"

Andrew Turner did not answer. But his old eyes were steely.

GRIEF, fear even, cannot for long keep sleep from young bodies

exhausted by work and strain and excitement, even if memories of

horror make that sleep restless and unrefreshing. In the dreary

small bedroom on the third floor of Five-twenty Hogbund Lane,

Jennie Marshall's bed was empty, but on the pillows of the big

double bed that took up almost all the rest of the space, lay an

auburn-ringletted head and one whose raven-black hair was pulled

back from an olive forehead by the ribboned pigtail. Though an

electric bulb still burned, the eyes of redhead and brunette were

closed, their young faces, wistfully childlike with the rouge and

lipstick washed from them, relaxed. Helen Reilly, the redhead,

kept tossing from side to side. Every so often Leah Meyers would

whimper in her sleep. The slightest unfamiliar sound, it was

plain, would awaken them both, screaming.

The slightest sound. But not the odor, faint at first, that stole into the room from the fire escape outside the window.

A distant tower clock bonged once. One o'clock.

Gradually, very gradually, the odor became stronger in the room, the sweetly pungent odor of ether that had still been perceptible about Jennie Marshall's lips when she'd been cut free from the pillar in Tracy's. Gradually Helen's tossings ceased, and the moaning in Leah's throat. Now they slept too soundly.

Too soundly.

Leah awoke, her head throbbing. A scream rose in her throat, but the palm clamped over her mouth stifled it She stared into the eyes that glittered down at her, then the rest of the face cleared and the terror became only amazement.

A finger lay against the mustached mouth at which she stared. The palm was removed. "Doc," Leah whispered. "Doc Turner! What—"

"Wait." The old druggist reached across her, took hold of Helen's flaccid wrist and pressed fingertips on her pulse. "She's all right," he sighed. "She is nearer the window and so inhaled more of the ether fumes than you did." Fumbling two clean handkerchiefs out of the pocket of his shabby coat, he smiled apologetically. "I hate to do this, but I can't watch her to keep her from crying out and talk to you at the same time." He made a tight roll of one of the kerchiefs and placed it between the girl's teeth; then he used the other to tie it in place.

"Now, my dear," he whispered, settling wearily down on the edge of the bed. "No, one can possibly know that I am here or that I have been here. You are quite safe in telling me all about it."

"About—" Leah's complexion was no longer olive-tinted, but greenish with pallor. "About what?"

"About what's going on at Tracy's, of course. Someone is preying on you young people who work there, and I—"

"You—you can't stop them, Doc." Fear shone in her dark eyes. "They—they're devils."

"I expect they are, but I've snared devils before—and I'll snare these." A feeble old man he was, wrinkled and stooped with age, his blue eyes faded. But the quiet conviction in his voice conveyed confidence. "How much are they taking from you?"

"A—a dollar-sixty every week. Ten percent of my sixteen-dollar salary."

"A dollar-sixty. It's a lot to you, but it doesn't sound like much to murder for. Multiply it by the ten thousand who work in that gigantic department store—"

"They don't all pay in, Doc. Only the junior salesmen and small-salaried employees below them."

"Ahhh." The look that came to Andrew Turner's face was one that many a criminal had recalled—sadly. And there were some who had seen that look just once—without recalling anything ever again! "Only the little people; the most defenseless. How many of those would you say there are at Tracy's?"

"I—I don't know exactly. Almost four thousand, I guess."

"Quite enough. All right, Leah. How do they induce you to pay?"

"We—it started a couple weeks ago. One Thursday one of the stock boys fell down an elevator shaft and got killed. We all thought it was an accident. When we went to our lockers to get our street clothes each of us found a printed slip that said, 'One more, tomorrow,' but we just laughed about it, thinking somebody was having some kind of joke. We waited to see what would happen on Friday."

"And what did?"

"A girl—Martha Trotter—fell through a window on the employee's staircase, between the seventh and eighth floors. It was just at quitting time, and she struck the street right in front of where everybody was coming out. She—"

"Yes," the old druggist interrupted. "I understand. And after that?"

"After that was another printed slip appeared in our lockers, Saturday morning. What this one said was, 'You need protection against such accidents as occurred to Tom Jenks—' that's the boy who fell down the elevator shaft—'and Martha Trotter. Premium, ten percent of your pay check.' We—of course we all knew what it meant by 'protection'."

"Of course. You are all of the post-Capone generation. But even if those slips were traced back to their originator, it could not be proved in any court that they were not simply advertisements for some form of accident insurance—although the rate is too high. Go on, Leah. To whom were you to pay this so-called premium?"

"There was a different agent for each department. The name on my slip..." The girl hesitated.

"Go on," Doc urged, leaning forward eagerly. "That's the most important of all. It is through that agent I shall be able to reach the master mind. Who is it?"

The girl's lips parted. Helen, awake now, gurgled in an evident attempt to stop her, but too late.

"Jennie Marshall," Leah Meyer's said.

THE bed-spring creaked as the old man started. "Jennie

Marshall—your own roommate was a member of the extortion

gang, and—"

"No!" Leah caught at the druggist's arm. "No, Doc. Jennie wasn't any more in that gang than me or Helen. She didn't know any more about them than we do. Please—"

"But—"

"Listen, Doc," the girl pleaded, her eyes starry with unshed tears. "Please listen to me. Jennie told us—she told us she was scared into collecting the money and turning it over, just like we were scared into paying it. But she never saw who she gave it to. She was awful scared, Jennie was. That's why she quit Tracy's, to get out of it all. We couldn't quit, we had to have jobs to live on, but Jennie figured Ben and her would get married and they'd let him out of the draft. And then he told her it was too late for him to get out of the draft and he wouldn't marry her—Oh, Doc Turner. You've got to believe Jennie wasn't in that awful gang."

"Of course I do," the old pharmacist said, soothingly. "Even if I didn't know Jennie well enough to know she wouldn't willingly get mixed up in this thing, the fiend who is engineering it would never involve himself with a hundred or more confederates. How did he arrange the final step in the collection?"

Leah spread her hand wide. "I don't know. Jennie didn't tell us. She only told us as much as she did because we were her best friends and she couldn't stand us hating her. Honest Injun, Doc." Her eyes widened. "Gee! We were awful worried, Helen and me, when she didn't come home last night, but we didn't dare say a word. We even joked about it to that snoopy landlady. We said—"

Helen jerked up, gurgling behind the gag she'd been to absorbed to remove, her hand pointing past Doc. He turned and saw the key turning in the lock! He lifted to his feet as the lock clicked.

The door opened and a revolver thrust in, fisted by a black glove. "I rather thought I'd find you here," said the tall, black-clad man who followed the gun into the room, "when you managed to elude the inept fool I had watching you."

Another man came in, his left hand holding an automatic, in his right the long-nosed pliers with which he'd turned the key from the outside. He shut the door.

Neither of the two was masked, and this was somehow ominous. The one who'd first entered was tall and lithe, graying at the temples, his long, narrow countenance graven with lines of bitterness, his mouth the too-small, too-red mouth of cruelty. His eyes slid past Doc to the bed, and deep within them was a flicker as of sheet lightning. "It is a shame to kill these young ladies."

"You said it, boss," agreed the other fellow, burlier, grosser in build and visage. The old druggist recognized, more by timbre than intonation, the voice that had spoken through a black mask the night before.

"I will do all the talking necessary, Gus," the tall man said, coldly. "Get over to that window and make sure the coast is clear."

Gus went around the bed to lean out of the window that Doc had left wide open. "You have no reason to kill these girls," the latter said, his tone as calm as though he were discussing the sale of a hot water bottle. "They know nothing at all—"

"So I learned, listening in on your interesting conversation." The old man became aware that the smell of ether had suddenly become stronger in the room. "But pardon me, Mr. Turner, I forget that I have the advantage of you. I am—well, the alias I am using at present is Martin Gadsden. My—accomplice, I suppose you would call him—is Gus Roscoe." Gadsden's look shifted to the bed again. "I imagine the auburn-tressed lass is Helen Reilly, and the other undoubtedly is Leah—er—Meyers. Yes?"

Doc's eyes were as hard, as coldly ferocious, as Gadsden's own. "May I suggest, Mr. Gadsden, that your badinage is in as bad taste as your cat-and-mouse act? Murder us, if that's what you intend, and get through with it."

Gadsden smiled, frostily. "I intend to murder all three of you," he purred, "but in my own good time. I rather imagine that I shall soon have to make another demonstration of the value of—accident insurance, and the Misses Meyers and Reilly will serve me very well as subjects. As for you, Mr. Turner..."

HIS lids narrowed, and two white spots bloomed either side his

thin, saturnine nose. "Last week, a very dear friend of mine died

in the prison where you had him incarcerated for a life term. I

feel that I owe it to him that your own death shall be more

lingering than I can arrange in this room."

Gadsden's left hand dropped into the pocket of his black jacket. "You know what this is, of course." He produced a gleaming hypodermic syringe. "It contains a rather large dose of scopolamine hydrobromide, the drug that renders a person amenable to orders."

"I don't need a lecture on materia medica," Doc snapped.

"Granted," Gadsden bowed. "I merely thought you might be interested in hearing about some of the ways in which I have used it for criminal purposes. However," he shrugged, "since you are not, suppose we proceed. Are you watching him, Gus?"

"You bet," Roscoe answered from the window, his automatic snouting at Doc Turner.

"Very well." Gadsden turned to the bed. "Your arm, please, Miss Meyers. Your right arm."

One could see the scream swelling the girl's throat, the terrible look in her dark eyes as of a snake-hypnotized bird. She lifted her arm to Gadsden.

He put his revolver in his pocket, transferred the glittering syringe to his right hand and bent to take hold of Leah's wrist with his left. Gus Roscoe bent over in a ludicrous imitation of his chief, and suddenly, oddly, toppled to the floor. Doc leaped, like a white-headed cat, on Gadsden's back.

Leah Meyers screamed then as another dark form surged in through the window. Gadsden, half-bent, whirled like a dervish. Doc lost his hold and flew from his perch, thudded into a wall. Gadsden clawed his revolver from his pocket.

Gun-crash drowned Leah's scream and an orange-red flare jetted across the room. Again. Martin Gadsden, jolted by the first shot, went down with the second, was a sprawled, inanimate heap on the floor.

"Doc," Jack Ransom yelled, darting around the end of the big bed, Gus's automatic still clenched in his big fist. "Are you hurt, Doc? Are you all right?"

"A little dazed, son, but quite all right." Faded blue eyes peered up at the carrot-headed youth. "You were down there in the backyard, as I suspected."

"Damn right, I was. I tracked you here and watched you climb the fire escape. I parked myself in a basement doorway across there, where I could watch, look and listen. When I saw that gorilla stick his head out, I decided it was time I climbed up, cat-footed, and sure enough I see him standing with his back to me, holding a gun on you. So I gave him the old rabbit-punch, and grabbed his heater just in time to use it on your little playmate. Say! You didn't imagine I'd let you go wandering around the neighborhood after midnight, with a pack of killers on your trail, did you?"

"No, Jack. I haven't enough imagination for that." Doc Turner gestured wearily to the dead man. "That was what beat him at the last. Too much imagination. He wasn't content with merely shooting me tonight, or having me knifed yesterday. No. He had to flaunt a warning first. He had to use scopolamine on me and the girls, and take us to his den under our own power. He wasn't content even to march us down the stairs. He imagined I must have found a safer and more discreet way of getting in and out of here, and he had to send Gus to see if the coast was clear. He had to keep talking long enough for you to climb up here, because he imagined my calm defiance must conceal some plan to trap him. Well," the tired old pharmacist sighed. "Mr. Gadsden's imagination cost him very dear."

"If you ask me, Doc," Jack grinned. "Anybody bucks up against you, imagination or not, isn't buying any bargains."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.