RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

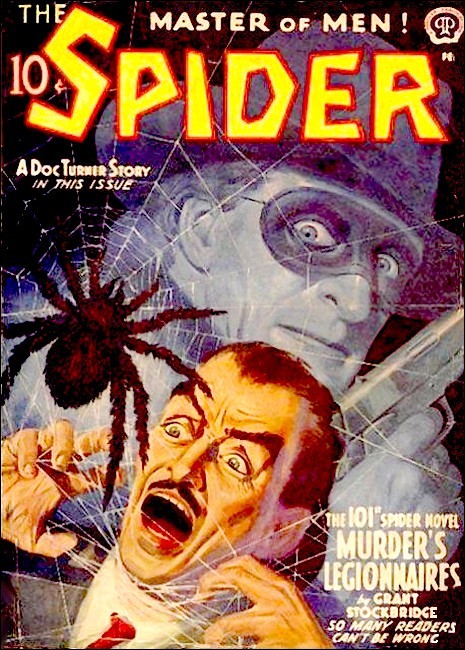

The Spider, February 1942, with "Dolls from Hell"

Who put the dreadful little dolls in the window of Doc Turner's drug store? Why was it that, each time one tumbled from its perch, its living image died horribly!

MORRIS STREET was thronged and raucous as usual. Trucks

pounded the cobbled thoroughfare shadowed by the "El's" sprawling

trestle. Hucksters shouted wares high-piled on their pushcarts,

lining the curb. Shawled housewives babbled shrilly in a dozen

alien tongues. Youngsters screeched at perilous play.

Two men peered into the display window of an ancient drugstore.

The younger spoke first. "They give me the creeps, Doc." Carrot-thatched and powerful, the lad emphasized by contrast his companion's stooped and slender figure. "I can't understand why the devil you stuck them in there."

"I didn't, Jack." White-haired Doc Turner tugged at his bushy, nicotine-stained mustache. "I don't know how they got into my window."

They were talking about the dolls that climbed a pyramid of bottled Turno-Tussin, the old pharmacist's own cough mixture. The mannikins, about half as tall as the length of a man's forearm, were so artfully fashioned as to seem almost alive; there was something grotesque about them. Something—evil.

"I thought it was queer," Jack Ransom said. "Since I've always known you disapproved of drugstores selling pots and radios and toys, to find you displaying dolls. That's why I called you out here to look at them."

There were four of the puppets. Two were clothed as men, two as women; but all wore a lusterless black fabric. Perhaps it was this that gave them their strange quality of malevolence; perhaps it was the malproportion of their limbs and torsos, or the slight distortion of their tiny features. "Hold on," Doc muttered. "There was someone this morning trying to sell me toys. A most annoying persistent fellow. I told him I wasn't interested, but he insisted on demonstrating some of his tricky gadgets anyway. He didn't show me any dolls, though."

"But he must have put them in here when you weren't looking, figuring that they would sell, and he could convince you to carry his line."

"Obviously." Doc's brow was furrowed. "What I cannot understand is how he managed it without my noticing. I was in the front of the store from the time he came in until he walked out."

"Maybe he slipped in later," Ransom suggested.

"With the door closed, Jack? Even if I was in the back room. I should have heard it open."

"Well—" Ransom was interrupted by a small crowd that rushed around the corner. Men were stooped over as though carrying some weight, and a curious whimper came from their midst despite the clamor of Morris Street, and the trample of hurrying feet. The crowd shoved up against the pharmacy's door, forced it open and pressed on in.

Doc and Jack worked their way into the store. Three men were laying a fourth on the gray floorboards, a broken form in overalls from which came that terrible whimper of agony.

"Phone for an ambulance, Jack," Turner snapped and knelt beside that shattered figure. The whimper faded as he reached for a grimy wrist. Blood appeared on the blue, twisted lips.

"Cheesa, Doc," came from one of the men who'd carried the fellow in. "Heesa work on roof scaffold, fixa cornice. All a sudden he walk right off end, fall right longside me. Heesa all smash—"

"Yes." Doc Turner gently put down the pulseless wrist, lifted wearily erect. "Yes, he's all smashed, but he doesn't feel it any longer."

A moan went through the crowd. Men removed their hats, women ceased their excited gabble. "I don't get it," muttered a fellow with an Irish brogue. "Why'd he do it, Doc? Everyone around here tells you all their troubles. Why'd Anton Svoboda kill himself?"

Doc's eyes were bleak. "He had no reason to. Only last night he was in here telling me how his oldest son was graduating from school. His wife was all over her prolonged sickness; and he himself had a good, steady job. Why he was sitting on top of the world. Look here, Tony." He twisted to the man who had spoken first. "Are you certain he jumped? He might have stumbled—"

"No, Doc. No. He jumpa. I hold rope on sidewalk keep scaffold steady an' watch close. I swear Anton jumpa down all by himself."

THE wail of an ambulance siren put an end to that colloquy.

The white clad interne plunged briskly into the ancient pharmacy

and a blue-uniformed policeman drove the crowd out of it. After a

while, Anton Svoboda was taken away in the Morgue wagon and

Morris Street settled back to its brawling routine.

"Doc!" Jack Ransom suddenly exclaimed. "Come here, Doc."

Turner joined him in looking down over the half-partition that backed the display window. A male-attired doll lay sprawled behind the high pyramid of bottles.

"Yes," Doc said, low-toned. "Yes. I see."

The face of the puppet and the face of the man who had jumped from a scaffold were identical. Exactly the same, even to a puckered scar at the corner of Svoboda's right eye. "Strange," he mused. "Very strange," and then his lips went thin and straight as he stared at the remaining dolls. "Jack," he murmured. "Jack, boy. As I recall it, the highest of the puppets was one dressed as a man, wasn't it, when we looked at them before?"

"Yeah. Yeah, sure. There was a man on top and then the two women below him and then another—Cripes!" Jack broke off, and a small muscle twitched in his cheek. "That's a woman on top now, and there's no room above her for another doll."

The other two dolls on the pyramid had also moved, so that each of them was now in the place of the one that had been above it before Anton Svoboda had died—had been killed by a fall just as the puppet that resembled him had fallen! "It is almost as if," Doc whispered, "they are marching up the hill to their deaths. But of course someone noticed the resemblance of the top one to Svoboda and removed it, and moved the others. A rather macabre jest."

"Macabre is right." Ransom's hands clutched the top of the half-partition, and his knuckles showed white. "Doc." His tone was queerly choked. "Doc. What were you doing at this window while everyone else was watching the ambulance doctor examine Svoboda?"

"What was I—?" There was something like terror, suddenly, in the old pharmacist's faded blue eyes. "You saw me—" The squeak of door hinges cut him off, and he turned to the hugely obese woman who entered. "Good afternoon, Mrs. Bergdorff."

"Ach! Such a goot-afternoon we should have not many here on Morris Street. Dot poor Sonia Svoboda, a widow left mit four little Kinder! I run right avay to see vot can I do for her und she chases me from her flat out. Vot wass it, Doc? Vy did Anton kill himself?"

"He didn't," Doc said in a strange voice. "He was murdered! And he will not be the last!"

The woman's eyes boggled at him out of her pink moon of a face. "Not—not der last?" she repeated.

"Look." The pharmacist gestured to the doll that was now topmost. "Look at that puppet. You know who she is, don't you?"

Mrs. Bergdorff looked, and her countenance was no longer pink but yellow. "Ja. Anastasia Paulopas."

Turner smiled, a waxen, artificial smile as alien to him as the uninflected tone in which he said, "Go tell her, Frieda Bergdorff. Go tell Anastasia that if she wishes to live she must obey the Seller of Toys. And remember, when your face appears in my window on a doll from hell—you too shall die! Go quickly."

The door slammed on the last of this sentence, and the woman fled. "Doc," Jack groaned. "What did you say that for?"

A shudder ran through Andrew Turner's slight form and his look was dazed. "It is true, Jack. That is the way the Seller warns his victims."

"She'll spread it all over the neighborhood."

Jack Ransom had faced many a perilous adventure with Doc Turner in forays against the criminals who prey on the helpless poor, had faced what seemed certain death, but never before had the blood drained so out of his countenance, leaving freckles vivid against a yeasty pallor. "That's what we always try to stop. What's got into you, Doc? What's happened to you?"

"What—what's happened to me?" Turner put his hand to his seamed brow, in a curiously fumbling gesture that hid his eyes from his young friend. When the hand dropped and he spoke again, it was once more in his own voice. "I want you to do something, Jack." It was thin with strain, though, and evidently on the point of breaking. "Pay no attention to what I say or do, from now on. Refuse any request I make of you, except this one. Do just the opposite, in fact—"

"What the heck, Doc? I can't—"

"Get out of here!" Doc cried, suddenly shrill. "Get out of here, you young fool. Don't you understand? You and all the rest of my people are in danger—and the danger comes from me!"

Jack got out, a gravely disturbed young man. He would have been even more puzzled and disturbed had he seen what Doc did after the door slammed behind him.

The old man stood very still for a moment, two vertical lines of pain creasing his forehead. Then, sighing, he went stumblingly toward the rear of the ancient pharmacy, around the end of the battered sales counter and through a threadbare green curtain.

In the shelf-walled back-room, Doc fumbled in a drawer and brought out a candle. He half-filled a mortar with water, stood the candle upright in this bowl, carried this over to the scarred roll-top desk at the end of the narrow room, set it down. His acid-stained fingers trembling, he struck a match and lit the wick, and then sank into the decrepit swivel chair that stood before the desk. Folding his hands in his lap, Andrew Turner sat motionless, staring at the small, bright flame. In Morris Street, the slum's early dusk was settling. The throng on its sidewalks dwindled, the hucksters rested their hoarse throats. It was supper-time. Almost surely he could count on an hour undisturbed...

JACK RANSOM scratched his red-thatched poll, bit his lips.

"Doc's gone nuts," he muttered. "Clean nuts. First he pulls that

trick with those dolls, then he tells that gabby

gossip—cripes! I better stop her before she talks to the

Paulopas woman!"

He ran the three blocks up Morris Street, but when he strode into the little restaurant, he knew he was too late. Behind the cash desk Anastasia Paulopas, stringy-haired, scrawny, sat staring into space. From the round, marble-topped tables roughly dressed men watched her. On their faces was the evidence that Frieda Bergdorff had been here and was already gone again to spread her tale of the dolls from hell.

"Look here, Mrs. Paulopas," Jack exclaimed. "You don't want to pay any attention to that bunk about the dolls. Doc was just ribbing—"

"Ribbing, hell!" a blue-jowelled truckman exploded, his chair clattering to the floor as he sprang from it. "Doc Turner don't rib about things like this."

Ransom swung to meet him. "Right, Dan Jordan!" He'd come to a sudden resolve. "Doc doesn't kid." This crowd in here were Americans and tough. If he could get their help... "He wasn't kidding when he told me, just now, not to listen to him."

"Says you." Jordan's paw gathered the lapels of Jack's coat in a huge clutch. "I suppose we're to listen to you instead. That it?"

"That's it, Dan. That's what he wants." Was it? "You all know how I've fought alongside of Doc whenever there's been trouble around here." Often they had fought blackmail by terror, fear spread by crooks and used to exploit the bewildered, superstitious aliens of Morris Street. This was another such plot, but this time it was the old druggist himself who spread the terror, and that fact twisted Jack's vitals with fingers of steel. "He's in a spot where he can't fight this one, but he wants me to fight it for him and he wants you guys to back me up."

"Maybe," Jordan grunted. "Maybe he does or he don't." Pallid faces crowded about them. "I wouldn't know about that. What I do know is if this thing's so tough it's got Doc licked, it's too tough for you or me or anybody else to buck. I know I'm damn glad my mug's not on one of them dolls, an' I'm prayin' it don't show up in his window."

"You an' me too," someone said hoarsely, and others agreed. Ransom stared about him, temples pounding.

"That's the way it is, Jack," Jordan growled, almost apologetically. "The only way you're gonna get this bunch to help you buck them dolls is if you get Doc to come in the open an' tell us to."

"Okay." Jack's lips were numb. "Okay. I'll get him to do that." He pulled free of the truckman's grip, pounded past the dreadfully still woman who sat behind the cash desk.

THE lights had not yet been turned on and Morris Street, dusk-filled, seemed desolate save for little knots of people

whispering here and there about a pushcart, or in grimy tenement

doorways.

A leaden hush invested the slum thoroughfare. The screech of rusted hinges as the pharmacy's door opened and shut was an eerie sound.

It startled Doc Turner out of his strange reverie. He heard footfalls, coming toward the rear of the store. Extinguishing the candle with a pinch of his fingers, he shoved up out of the swivel chair and went through the green curtain.

He saw no one in the store.

The footfalls were still audible. They reached the sales counter, stopped.

With his heart pounding, Doc went around the end of the counter.

NO taller than half the length of a man's forearm, a mannikin

dressed in black was setting a tiny black sample case on the

floor before the counter. It straightened, turned up to him the

dark, hook-nosed face of the toy salesman who had been so

annoyingly persistent that morning.

"Good evening," the living puppet said, and it should have seemed strange to Doc that its voice was not tiny but full-rounded. "I have brought you some more dolls."

Turner nodded, wordlessly. The mannikin bent again to its minute black valise and with incredibly tiny hands began to unbuckle its threadlike straps. "You will be careful to place them in your window unobserved—as you did with the others."

"I will be careful," Turner said tonelessly. "No one—" The squeak of hinges pulled his head to the front of the store. "Jack," he exclaimed. "I thought I told you to—"

"Stay out of here." The carrot-head let the door slam, came on in. "Sure. But I—" He checked. "I'll talk to you when you get through with your customer."

"I am not a customer." Quite without surprise, Doc saw that the man in black was now normal size. "I am trying to persuade Mr. Turner to stock a little novelty of my own invention." He straightened, bringing up out of his valise—itself now of full dimensions—a varicolored metal disk attached by a ratchet to the handle by which he held it. "If you can spare the time," he smiled blandly, "I should like your opinion of it."

"I don't know anything about toys—Toys!" Abruptly small muscles knotted, ridging Jack's blunt jaw. "You sell toys, do you?" he said very softly. "Maybe I know something about you, Mr.—"

"Shedrim," the man filled in the questioning pause. "S. Shedrim." The wheel was turning with a muted whirr as his brown hand flexed on its handle. "You know me, sir?" There was something fascinating in the way that, as the disc whirled faster and faster, its helter-skelter blobs of vivid color became a spiral pattern that flowed endlessly to its center. "I should not be surprised if you did," Shedrim purred. "Perhaps you have dreamed of me in the night."

The center of the spinning disc was a brilliant spot of light that reached out and pulled Jack's eyes to it. "Dream?" The spiraling lines of color flowed into it, interminably. "Why should I dream of you?"

"Many do." The toy-seller's droning words merged with the wheel's low whirr, and it was a drowsy murmur. "Very many dream of me in their sleep. Sleep," he murmured, the colors of the wheel graying as they gathered into the single bright spot on which Jack's eyes were focused. "Sleep," the disc droned, gathering Jack into its gray spiral so that he flowed with the spiral into the brightness at its center...

DUSK was dim in Andrew Turner's drugstore, and Jack Ransom was

alone with Doc. "Look, Doc. I came back to—to..." He

hesitated, pulled the edge of his hand across his eyes. "To

what?" He asked it plaintively, as a small child might, losing a

thought it was still unused to. "There was something awful

important I wanted to say, but I can't think what it was."

THREE blocks up Morris Street, the little restaurant of

Anastasia Paulopas was empty of customers, but Anastasia herself

sat behind the cash desk, staring. She did not stir even when her

door opened and a thin man, black-clothed, his face dark in the

shadow of his broad-brimmed black hat, entered.

The man came up to the cash desk, put a business card on the glass coin slab. The words on the small, white rectangle said:

S. SHEDRIM

Seller of Toys

Breath whispered from between the woman's uneven teeth. "What

do you want?"

Shedrim's smile was sardonic. "Nothing for myself. I am merely drumming up trade for the storekeepers who stock my goods. Druggist Turner, for instance, is displaying a line of my dolls and there is one I am sure you will want to buy, even though it is quite expensive."

"Expensive?"

"It will cost you five hundred dollars."

"Five hundred—!" Anastasia's hand clawed at her throat. "That's all I have been able to save for my old age, slaving here eighteen hours a day."

"This is a very special doll," the Seller of Toys murmured. "Very fragile. If you don't buy it by nine-thirty tomorrow morning, it might fall and be broken." His fingertips tapped on the coin slab and Mrs. Paulopas saw that their nails were very narrow and very thick, curving to sharp points. "You wouldn't want that to happen, would you?"

"No," Anastasia Paulopas moaned. "Oh, no-o-o..."

ON Hogbund Lane, Madame La Rose, born Rosa Meier, polished the

many dangling curlers of her permanent wave machine with chilled

and clumsy fingers. Perhaps she was too absorbed in the strange

tale Frieda Bergsdorff had brought to her beauty parlor to hear

the tinkle of her door bell. Perhaps it did not tinkle. At any

rate, the tall, sharp-chinned stranger appeared beside her

without warning.

"I am S. Shedrim," he said, "Seller of Toys." He seemed not to notice her gaping mouth, the terror in her mascaraed eyes. "In the drugstore window on Morris Street there was a doll this morning that resembled Anton Svoboda. It fell."

Madame La Rosa's rouged lips moved. She was trying to make the words, "I know," but the sounds wouldn't come.

"There is a doll in that window now," S. Shedrim went on, "that resembles you. The price of that doll is three hundred and twenty-five dollars. It is worth it to you. I should advise you to purchase it before a quarter to ten tomorrow morning."

As the man went out, she noticed that his feet were small for a man. Or for a woman. It was not till afterwards that she started to wonder how he knew that her balance in the savings bank was exactly three hundred and twenty-five dollars plus a few cents.

IN the window of Andrew Turner's ancient pharmacy, great pear-shaped bottles were filled with colored light by the electric

bulbs behind them; green light in one, a deep, liquid red in the

other. The red light spilled out of its bottle, lay incarnadined

over the dolls that completely covered the pyramid of Turno-Tussin bottles, seeming to be climbing it. Artfully wrought dolls

they were, the face of each a miniature replica of the face of

someone who ran a small business on Morris Street or somewhere in

the neighborhood.

Morris Street was raucous again, its cracked sidewalks thronged. No one passed Turner's window without glancing into it, but everyone hurried on, each with fear-filled eyes.

AT eleven-fourteen S. Shedrim appeared in the little basement shop where Giuseppe Manero, shoemaker, worked at his last. "I am the Seller of Toys."

Manero's knife slid evenly through heavy leather, shaping a half-sole. "I no gotta bambini," he said without looking up. "I no needa de toy."

"The toy you are going to buy tomorrow at noon is not for a bambino. It is a doll, Mr. Manero, and it looks just like you. It will cost you four hundred and seventy dollars."

Giuseppe looked up, now, but there was no more expression on his countenance than there would be on the brown shell of a walnut. "No," he said. "Not four cent. I gotta no use for doll."

A sardonic smile crossed S. Shedrim's triangular, dark visage. "Perhaps you have not heard about Anton Svoboda?"

"I hear." Manero lifted from his bench. He raised his curved, keen knife. "Out! Get outta here!"

Shedrim took a backward step. His own hand came up out of the coat pocket in which it had been buried, but there was only a cigarette lighter in it. "Why get excited?" he murmured as he snapped on the lighter. He held it up apparently while with his other hand he fumbled for a cigarette. "I am merely trying to help out my customers."

"You no foola me." Manero watched the bright little flame warily. "No doll wort' four hundred doll'."

"Perhaps not," Shedrim purred. "But this is really a very interesting doll." That little flame was steady before the cobbler's face, and it was extraordinarily bright. "It can climb, climb, all by itself." It held his gaze, so brilliant in the dim shop. "It can climb and walk and it can sleep," Shedrim droned. "Sleep, Giuseppe Manero. Sleep... sleep... sleep..."

At eleven twenty-one the telephone rang in the booth in Doc Turner's store. Doc answered it. At eleven twenty-three someone noticed that a doll had fallen from the pyramid in the window and lay sprawled against the plate glass. The doll's face was dark and corrugated like the shell of a black walnut.

At half-past eleven Jimmie Kaslow shambled into Manero's basement shop to get his father's shoes, so the old man could go to work in the morning. Giuseppe was hunched, as usual, on his bench, carving out a piece of leather for a half-sole. Jimmie waited for him to finish, watching how neatly the sharp knife followed a curve visible only to the cobbler's inner eye.

Manero held the board-like piece of leather steady against his blue apron, cut toward himself. The knife came to where it should turn to shape the toe—and kept on going. It slid, quite as if the cobbler intended it to do, into the grimy apron, into the flesh beneath—into his heart.

Giuseppe Manero died without a sound...

NEWS traveled fast in the slums. Even faster than S. Shedrim,

though he must have traveled very swiftly, so many did he call on

that night, before midnight.

At midnight, Doc Turner put out the store lights, locked his door—from within. He went slowly back through the dimness in which the white-painted, old-fashioned showcases glimmered eerily, went through the curtain in the partition at the rear. He carefully adjusted the curtain so that its edges hung close against the frame of its aperture, stuffed absorbent cotton into the peephole in the partition through which he could watch the front of the store while he compounded a prescription. This done, he scratched a match and lit the candle still standing in the water-filled mortar on his desk.

The candlelight, slanting upward, cast strange, sharp shadows on the face of the burly youth who all evening had sat slumped in the swivel-chair before the desk. He stirred now, sat up. "Ready, Doc?"

"Not quite." Andrew Turner stood very still, looking down at Jack. "There is something I must say before we begin." New lines cut into his gray visage and his eyes were hag-ridden. "We are about to trifle with forces about which science knows very little. We may fail altogether, as I failed this afternoon. We may succeed. Or—" pale lips twitched under his bushy, nicotine-stained mustache—"or far worse, somewhere between success and failure, you may be left—a mindless hulk!"

The words whispered into a silence against which the city's nocturnal rumble thudded without impression. Jack Ransom's hand closed on the edge of the desk till it was a great, bony fist, the knuckles white.

When he spoke, his voice was low. "Didn't you say it's our only chance of licking this monstrous murderer?"

"Yes, Jack, it is our only chance."

Jack's look drifted to the door which could lead him out to the side-street—to safety. He turned back to Doc and his grin was boyish, endearing. "Okay. What are we waiting for?"

JACK RANSOM did not show up at the garage where he worked, the

next morning.

All that morning white-faced, wide-pupiled men and women came into Turner's drugstore. Each transacted a whispering deal and hurriedly departed, each with a bundle about half the length of a man's forearm. All afternoon they came and went. The last one left at eleven, and in the display window only two dolls were left, crumpled on its floor.

At midnight Andrew Turner put out his store lights and locked the door—again from within. He went slowly into the back-room. Tonight a single shaded bulb glowed here, and on the white-scrubbed prescription counter beneath it rested a package wrapped in brown paper, the size and shape of a double-thick brick.

Doc let himself down into the decrepit swivel desk-chair, settled himself to wait for the next act in this strange drama. What it would be he had no idea, but he knew that he would have no say as to his part in it, and beneath his blue-veined, almost transparent eyelids there dwelt a presage of horror yet to come.

The city's nocturnal noises pounded at the door beyond the end of the desk. The door was moving inward, silently. It whispered shut. A shadow moved into the cone of luminance from the single bulb. It was S. Shedrim, Seller of Toys.

Wordlessly, he set his black sample case down on the counter, unbuckled its straps and opened it. His hand closed on the waiting bundle. The talon-tip of his forefinger ripped the paper down one of the sides, riffled the stacks of money. "It is all here?" he asked.

"All," Doc replied tonelessly. "Thirteen thousand, eight hundred and fifty dollars."

"Correct." The bundle vanished within the sample case and the deft hands strapped it shut again. "The dolls cost me three hundred, other expenses about a hundred more. A profitable deal. We should drink to it before I leave." His narrow, slanted eyes drifted along the neat row of bottles above the counter. "Ahh!" He took one down, read the label aloud. "Spts, Frumenti. I am sure any whiskey you use in your prescriptions must be the best available. But glasses—" He crossed to the glittering array of graduates racked over the sink.

He returned with two four-ounce measuring glasses. "Shall I pour?" His hands were very deft. It would have required a quick eye to notice the pinch of crystals that went, with the amber liquid, into one of the graduates—the one which, half-filled, he shoved towards Doc. "Come," he rapped out. "Drink with me."

THE old pharmacist came to the counter. There was about his

movements, a curious quality of willessness. His acid-stained

fingers closed about the glass, raised it in imitation of the man

in black.

There was mockery in S. Shedrim's tones. "To the end of all memory and all regret—" A hand came over his shoulder from behind, clamped his wrist. Another gripped his opposite upper arm, clenched tight. "All right, mister," Jack Ransom said. "I'll take care of the doings from now on."

Doc froze, the glass uplifted to the toast, eyes blank, unseeing. "Try your whirligig on me now," Jack chuckled. "See if it works."

"You remember that?" There was only a trace of surprise in Shedrim's calm voice.

"I've been told about it," Jack chuckled, "by Doc. He remembered your starting to show it to him, the first time you were in here. You were pretty smart, weren't you? You fixed things so the only one who could get in trouble was Doc. You didn't break any laws, going around telling people to buy your dolls from him. You had a right to collect from him what he was willing to pay for them. Svoboda and Moreno killed themselves, you weren't anywheres near them when they died. You hypnotized me to keep me from butting in, and you hypnotized Doc so he'd do and say everything you wanted him to, by post—post-hypnotic suggestion. You only slipped up on one thing."

"What was that?"

"Just that you didn't realize Doc was smart enough to figure out why he couldn't remember throwing the Svoboda doll off them bottles, when I told him he had, and why he couldn't help saying what he did to Frieda Bergdorff. Even then he couldn't disobey you, but he could do things you didn't tell him not to. Like hypnotizing me himself, right over your job, so I could hide and grab you when you came in."

"Yes," S. Shedrim murmured. "He could do that. But he could not break my own power over you." He twisted in Jack's grip, stared into the youth's eyes. "Release me!"

As if the command was a whiplash across them, Jack's hands jerked away from their holds. "You cannot move," Shedrim snapped, "till I say you may."

There were two rigid, silent figures now in the back-room of the ancient pharmacy.

Shedrim laughed softly to himself as he put his graduate down on the counter. "I didn't come prepared for this emergency," he purred, "but the omission is easily remedied." He opened a small cabinet inset into the shelves over the prescription counter, selected a small bottle from within it. When he opened this to sift some crystals into the graduate's amber contents, the pungent odor of bitter almonds came from it. "I intended to destroy this glass and leave the other. This will be even better."

Smiling, he watched the crystals dissolve, lifted the glass. "Take this." Jack did not stir. "You may move," Shedrim said. "Take this." Jack's hand came up and took the graduate from him.

The man in black stepped back so that both the others were within range of his slanted, evil eyes. "Now, Mr. Turner—Mr. Ransom—drink!"

A seamed, acid-stained hand, a freckled, strong one, lifted two glinting graduates to lips. And stopped!

"Drink!" S. Shedrim barked, a sudden glisten of perspiration on his dark brow. "Drink it down."

Neither of his victims moved.

Shedrim's lips snarled back. "I'll make you, then." He reached to shove Jack's glass against his teeth. The carrot-head's left fist arced up, jolted the black-clad man back into Doc's bent arm.

Doc's whiskey spilled over Shedrim as he fell, into his gasping mouth. He struck the floor and lay still.

A long shudder shook Andrew Turner's slight frame. The light of reason came back into his blank eyes. "That's done it," he murmured. "The fellow's gone, and with him his control over us."

THE alcoholic liquid made a splotch on the dead man's twisted

countenance, where it washed away the dye that had darkened it.

"I know him now," Jack exclaimed. "He was in the garage last

week; said he was from a credit rating agency and wanted a

financial statement. The boss laughed, told him he was busted.

That's why this Shedrim knew how much to ask from everybody. But

why didn't he just hypnotize them all and make them give it to

him?"

"Because not everyone is as good a subject for hypnosis as you and I. He could make a clean sweep by trading on the faith my people have in me."

"Yeah." Trembling fingers shoved through a tousle of carrot-hued hair. "And he figured on cleaning up all traces by poisoning you, making it look like you'd poisoned yourself by accident. But why didn't it work out, Doc? What made me slug him? One second I had to do what he said, the next I was knocking him down. I don't get it."

"You forget, son, that you were not doing as he said, nor was I. Neither of us were drinking the whiskey he'd dosed with cyanide. That was where he made his mistake. He didn't know that you've been hanging around here long enough to be aware that anything kept in that cabinet is a deadly poison, and what he said to you about destroying the graduate I had been about to drink from informed me my liquor was also poisoned. You can make a man do many things under hypnosis, but you cannot make him kill himself."

"How about Svoboda and Moreno?"

Doc spread his hands. "They did not kill themselves. Anton walked off the end of a scaffold, Moreno's hand slipped as he cut out a sole. What Shedrim did, by post-hypnotic suggestion, was to distort their sense of sight as he did mine when I saw him as a mannikin. Svoboda undoubtedly saw the scaffold projecting a foot or more beyond where it actually ended. Moreno saw the leather as being longer than it actually was. Understand?"

Jack shrugged. "I—I think so. But you haven't explained why I slugged Shedrim."

"It was a natural reflex, with you, when he tried to push the whiskey into your mouth and he'd given you no command to forestall it. Or, rather, he'd countermanded that command. Remember? 'You cannot move,' he'd said, 'till I say you may.' And then he said you might move when he told you to drink."

"Yeah. Yeah, I get it now. All except your spilling the whiskey into his mouth."

Andrew Turner looked down at the Seller of Toys, sprawled motionless as a broken doll on the bare, gray floor of the ancient pharmacy. "That was an accident, son," he smiled wanly. "What we call an accident, at any rate. Remember, Jack, Shedrim had murdered two men in such a way that no judge could possibly convict him. No human judge—but there is a Judge not human and He administers a Law more wise, more just, by far, than any man-made law..."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.