RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

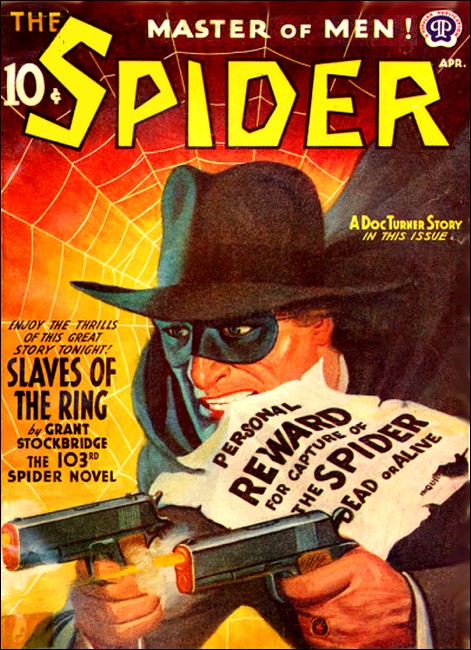

The Spider, April 1942, with "Corpses Pay Dividends"

Lovely Honey Morse sprang to riches from the dregs of Morris Street. Yet when a nameless menace threatened the neighborhood of her birth, she rushed to Doc Turner, patron of the slums—unaware that her grim message would falter on lips sealed with lead!

SHE entered the ancient drugstore through the front door, leaving behind the raucous Saturday night tumult of Morris Street. Her tiny feet seemed to float above the gray and rutted floor.

"Honey!" Andrew Turner exclaimed. "Honey Morse!"

The years had frosted Doc Turner's silken mane and the bushy mustache that concealed his sensitive mouth. On his bony, hollow-cheeked countenance Time had written in fine lines his kindliness and twinkling humor, his long record of service given. He was no youth to thrill to feminine loveliness, but a light shone in his faded blue eyes as Honey Morse hugged him and pressed a kiss on his dry old lips.

"Gosh, Doc!" she sighed. "It's swell to see you again."

"Let me look at you, my dear." His gnarled hands held her away so that he might do so. "How you've changed," he chuckled fondly, "since I last saw you and gave you a handful of jellybeans?"

"Why, the idea, Doc!" Honey's pout made a dusky rosebud of her mouth. "I'd have been insulted if you'd given me jellybeans the last time I was in here. I was a grown-up young lady of sixteen."

"All elbows and knees!" The old man smiled reminiscently. "Your cotton dress was patched and shabby and too short for your gangling frame. Now you are—let me, see... yes, all of twenty, lovely as a dream. The cost of your furs is more than your mother spent clothing you and your five brothers and sisters all the years I've known her."

A shadow crossed the girl's cameo features. "How—how is mother, Doc?"

"Don't you know, Honey?"

"You know I don't. You know she chased me out of the flat the day I took that job in the chorus of Gertie's Garter. She—she's never answered my letters or cashed one of the checks I sent her. Please tell me, how is she?"

"Aging, Honey, but still working hard at the factory." The old druggist's smile faded. "But you—you've changed in other ways, my dear. There was only happiness in your eyes the last time I looked into them, gaiety and young dreams. Now there is only disillusionment; and wisdom learned the hard way and—yes—and fear."

"Fear!" she cried. "How silly! What have I got to be afraid of?" But Doc felt a shudder run through her and knew he was right.

"Tell me," he said softly. "Tell me, Honey Morse, why you've come back, in your silks and fine furs?"

"Because I was born here." She pulled free from him, but her gloved, small hand reached to the heavy frame of a once-white showcase, as if for support. "I was born here and grew up here, and I know how hard these people work for the little they have, and I think it's a darned, rotten shame that—Look, Doc. You haven't changed, have you?" She peered anxiously at him from under artfully plucked brows. "You'd still go to bat for them against anyone who tried to kick them around?"

A new tenseness came to the old pharmacist's stooped, feeble-seeming body. "No," he said gravely. "I haven't changed."

"I didn't think you could have, and so when I heard—" Honey broke off and glanced over her shoulder to the door, and beneath her shell-pink ear the sudden, frightened flutter of her heart was plain.

Looking past her, Doc Turner saw only the usual throng of shawled housewives and their heavy-limbed, labor-weary men. Beyond was the glare of wire-hung electric bulbs on the pushcarts, high-piled with the bright colors of their oranges and tomatoes, scallions and green lettuce. The raucous shouts of the hucksters came in from Morris Street, the polyglot chaffering of their customers and the rumble of trucks, and the laughing screams of the children at dangerous play in the cobbled gutter.

There was nothing out there of which Honey Morse should be afraid. Nothing at all.

She turned back to him. "If they gave out medals for being a dope, I'd get one all platinum and diamonds." Her mouth twisted with a wry, impish grin, but between their long lashes her eyes were terrified. "Listen, Doc. There's a—"

It sounded like a truck's backfire, but it jolted Honey away from the showcase and into Doc's arms. Agony leaped into her eyes, a black flame, and twisted her mouth.

She muttered the word, "Triangle." It was utterly meaningless, but with terrible effort it was repeated. "Tri—triangle," and then the warm vibrance was gone from the frail form in Doc's arms and there was no longer any pain in Honey Morse's eyes, nor fear. Nor life.

He laid her gently on the floor and went to the door.

No one in the throng knew who had fired the shot. How could they? It had sounded precisely like a backfire and the marksman had needed to pause only momentarily in the doorway before he melted away into the crowd.

"IT has taken the police a week," the tabloid gossip column remarked, "to find out they can find out nothing about the fatal shooting of gunned dancer Honey Morse in that slum drugstore. A certain Cafe-socialite, however, thinks he can do better. He has let word get around that he will pay Ten grand for information that will break the killing."

"The guy is called Foster Starret, Doc."

Barrel-bodied, carrot-thatched, Jack Ransom was in his own burly way as great a contrast to the old pharmacist as the flower-like Honey had been. "I got the tip from Gimpy Moran, who parks his hack in the garage where I work."

"Starret," Turner mused, absently leafing over the paper's pages. "Should I know him?"

"Not unless you've been spending your time hitting the night spots after you close up here."

"Hmmm." The druggist ignored his young friend's outre suggestion. "What did this Gimpy know about him?"

"Nothing much. Starret always hangs around the Heron Club, midnight till closing. Honey Morse was—Well, you know. He lifted her out of a cheap girlie show and got her the spot there at the club and a guy like that don't do things like that just to be a Santa Claus."

"No," Doc sighed. "I don't suppose so."

"Nobody seems to know where this Starret gets his dough," Jack went on, "but he's sure got it. He's a free spender, tips big and put out plenty on Honey, but—Hey! You ain't listening to me."

"Read this, Jack." Doc's acid-stained hands pressed the paper flat on the sales counter behind which he stood. "This ad."

In the center of a white page bordered with dollar signs, was this legend:

!!MONEY!!

You Need It. We Have It.

Come and Get

It.

You don't have to PAWN your furniture!

You don't have to get your boss to SIGN your note!

You don't

have to put out for a PHONEY service charge!

LOWEST INTEREST

in

THE CITY

PAY BACK $1 A WEEK!!!

This is your chance to buy nice clothes,

a radio, to take a vacation in the country,

to get those

eyeglasses or false teeth you've needed so long.

Pay the bills that have been worrying the life out of you.

Come and Get It!

!!MONEY!!

"Okay." Jack was puzzled. "So what about it?"

"It's couched in language simple enough for anyone who's literate at all to understand. The terms, especially repayment of only a dollar a week, are irresistibly tempting, and then there are those diabolical suggestions of what the money so easily borrowed could purchase for the borrower."

"Yeah. Yeah, it's a swell ad. It almost makes me want to run right around and ask for a couple bucks myself."

"That, my boy," Doc said softly, "is precisely what you are going to do."

Jack stared. "Nix, Doc. I've got a radio and I don't need any false teeth, and if I owed any bills it's the guy I owed them to who'd be doing the worrying. What for should I start in with a bunch of loan sharks?"

"Did you notice the name at the bottom of this ad?"

"No. Why?"

"Look at it."

The youth read:

TRIANGLE LOAN COMPANY

345 Morris Street

One Flight Up

and looked up. "Triangle. That's the word Honey gasped out just before she died, and you think—Aw, no Doc. No. How could there be any connection?"

"I don't know." The seamed old face was bleak. "I haven't the least idea. But she fought off death for a terrible instant to utter that one word and so it must be the key to what she came to tell me—and the reason she was murdered." He pulled in breath. "She was shot down, Jack, in cold blood to keep her from warning me of some scheme against her people and mine, and that's a plain indication of what kind of scheme it is. Whatever life Honey Morse lived, she died for her own people. For her sake, and for theirs, I dare leave nothing untried that might keep her from having died in vain."

"Okay," Jack grinned. "Okay, Doc. I still think it's goofy but I'll go."

When he returned, a half hour later, he was still grinning—triumphantly, now. "If that outfit's not on the up-and-up," he announced, "I'm a brass monkey. Cripes! I went to school with both the stenog there and the fellow who interviewed me. The worst thing either of them ever did was slip a slug in a subway turnstile."

Turner was not satisfied with this. "They're not the officials of the company, are they?"

"On the books they are, but not really of course. Look. Dick Barton told me the whole setup. Seems like some big bank figures a chance to make money in this sort of thing, but the law says they can lend only to business firms with assets, or to real estate owners or others that can give them security. So they set up this dummy corporation and go at the thing like it's a department store, cut prices, advertising, babying the customers and all like that.

"It's worked out swell, too. Once the word got around how decent they are, they started doing a whopping business. Why, in the six months since they started there's tenements—two of them right around here on Hogbund Lane—where every last family has a loan from the Triangle."

"You don't say."

"Why not, the way they treat you? They just ask you where you work and how much you get, and you sign a couple of papers and—whango—you've got your money. Cripes! They even pay for the insurance themselves—"

"The insurance?" Doc broke in, sharply. "In their name?"

"On your life, for the amount of what you owe them. Fifty dollars, a hundred maybe. Gees, Doc, not even you can make anything wrong out of that."

The old pharmacist smiled, faintly. "We've worked together so long that you can almost read my mind, can't you? But you're right. That is merely the sort of arrangement a bank would insist on, to protect itself against loss. What bank is it, by the way?"

Ransom spread his hands. "Dick don't know. The lawyers ain't sure the setup's quite legal and so as far as the corporation papers go, the Triangle Loan Company's just him and Jen O'Hare and a geezer named Chase who's the manager and the only one who's on the in. Well, Doc, I guess we can forget about that Triangle being the one Honey Morse meant."

"I'm afraid so." Turner sighed, and for a moment there was a brooding silence in the ancient drugstore. Then, "Jack. If you've a minute more to spare, I wish you'd drop in at Lapidus's tailor shop and tell Moe I'll want to rent a tuxedo outfit for tonight, complete with wing collar and black tie."

"A—" Jack could not have looked more amazed if a Tyrannosaurus had come waddling down Morris Street. "What in the name of reason do you want with a tux?"

Doc Turner tugged at his mustache. "Oh," he said airily. "I might hit a few high spots after closing." There was an odd twinkle in his eyes. "You might also ask your friend Gimpy Moran to call around for me in his cab, as soon after midnight as he can manage."

JACQUES LA MONTAGNE'S tail coat was immaculate, his black

mustache waxed to needle points. Maître d'hôtel of the

swank Heron Club, he was the city's arbiter of social

distinction. Those to whom he opened the sacred plush rope

barrier were of the elect, those whom he shut out were forever

damned.

His hauteur was at its dignified best as he fixed a frosty eye two inches above the little old man in an ill-fitting, obviously rented dinner jacket. "I am veree sorry," he said in a tone that meant he was not sorry at all, "but all ze tables are taken."

"My, my," Doc Turner murmured, "you've certainly grown up, Jackie Berg, since you used to run around Morris Street with the seat out of your pants." Jacques looked down—and went dough-yellow around the gills. "Doc! My Gawd...!" He kept his voice down, but he could not keep the shrillness out of it. "Gees, Doc, if anyone heard you—I'm supposed to've come here straight from the Brussels Ritz—"

"Instead of Meyer's Dairy Restaurant," Turner chuckled. "All right, Jackie. I won't give you away—provided you take me to Foster Starret's table..."

The man who sat alone at the table was older than Doc had expected. There was gray at his temples and small wrinkles at the corners of his veiled eyes. But there were no marks of dissipation on his round, yet gaunt-seeming, countenance. His nostrils flared as the old druggist stopped beside him.

"Mr. Starret?"

"Yes?"

"My name is Turner. Andrew Turner. Honey Morse died in my arms."

Not a muscle moved in Starret's face, but it was abruptly a hard mask, expressionless as his tone. "Sit down." Jacques, hovering discreetly out of earshot, sprang forward to pull out the chair for which Doc reached. "Monsieur weeshes to dreenk, n'est-ce pas?" he inquired.

"Of course," Starret answered. "What will you have, Mr.—er—Turner?"

"Nothing. Oh, a little sherry if I must." The headwaiter hurried off and the old man turned to his table companion. "Mr. Starret," he began, without preamble, "as she died, Honey gasped out a single word that I'm sure is the clue why she was slain. I understand that she was—well, that you were together a great deal and it has occurred to me that you might understand to what, or whom, she referred. The word was—Triangle."

If Doc had expected some reaction, he was disappointed. "Triangle?" Starret repeated, tonelessly. "No. It has no meaning for me."

The orchestra crashed into rhythmic cacophony and chairs scraped as couples rose to dance. "Have you," Doc persisted, "by chance ever heard of the Triangle Loan Company?"

That was the precise moment a waiter chose to come in between them and deposit on the table the sherry he'd ordered. When the servitor withdrew Starret's expression was still inscrutable. "Mr. Turner," he murmured. "Aren't you wandering rather far afield? How could a loan company have any possible connection with Honey's death?"

"I hoped, knowing how anxious you are to avenge her murder, that you could help me find out."

"You are not answering my question," the other pointed out. "Simply because the company's name includes the very common word she uttered—"

"And because its backers conceal their identity. Mr. Starret!" A note of steel crept into Doc's tones. "I intend to discover who those backers are if I have to go to the State Banking Commissioner himself. You see," he smiled deprecatingly, "I have a queer idea, an old man's senile fancy perhaps, that when I find them, I shall also find those responsible for that girl's death. You would be glad of that, would you not?"

Starret's hand closed into a fist on the cloth. "Glad of it? If I thought—Look here," he broke off. "This is a fantastic notion of yours, but if it has any justification, an official investigation would warn the people you suspect. I happen to know someone who may be able to give us the information in confidence." He pushed up out of his seat. "I know him well enough to telephone him even at this hour. Will you excuse me please?"

He strode off. Doc's fingers closed around the stem of the sherry glass and raised it. His lips moved, as if he were making a silent toast.

Across the room, screened from him by the dancers, a bediamonded and besotted dowager mumbled incoherencies into a portable telephone that had been brought to her table and plugged in there.

Foster Starret did not sit down when he returned. "It looks as if I'll have to apologize for thinking you a bit off." His frozen calm now seemed like thin ice over a turbulent, boiling rapids. "My friend refused to talk over the 'phone, but he offered to tell us something very interesting if we'd come to his home. I told him we'd start right over. That suit you?"

"Naturally."

"Come on then. The doorman's bringing my car around."

THE hundred horses under the coupe's huge, gleaming hood

champed in muted protest as a red traffic light held them in

leash.

"They shouldn't hold traffic up at this time of the morning," Doc murmured. "There isn't another car on the street or a soul on the sidewalks."

"I agree with you." Starret put a cigarette between his lips and leaned over to reach for the dashboard lighter. "It's wise, however, to stop—oops!" The glowing little rod slipped from his fingers and fell between Doc's feet. "That was clumsy of me. If you don't mind, Mr. Turner. I can't reach it..."

The druggist bent to retrieve the thing. Something thudded against the base of his skull and he blanked out.

THE room in which Doc Turner returned to painful

consciousness, was very small. A huge safe took up most of the

space. Other than this there were only a flat top desk and the

swivel chair in which Doc slumped, and to the arms of which his

wrists were lashed.

There was no window in the room, but one wall was a partition that did not quite reach the ceiling. The upper half of this partition was frosted glass and the yellowish light that sifted through it was bright enough for him to read the gilt letters across the front of the safe:

TRIANGLE LOAN COMPANY

Doc couldn't get out of the chair but he could swing it around with his feet, and it was well-oiled so that it made no noise as he did so. The partition door was closed. The lettering on the glass in it was reversed, but it was easy to make out what it said:

CLARENCE CHASE, Mgr.

The light on the other side of the partition laid on it a shadow Doc recognized. Foster Starret. He was standing and something about the way his head was thrust forward conveyed a sense of tense waiting, almost of dread.

The old druggist wasn't gagged. He recalled that 345 Morris Street was a two-story taxpayer building, with a hardware store on the ground floor and offices above. A clock on the desk told him it was three-seventeen. The store would be closed at this hour and nobody would be in the offices. He could scarcely yell loud enough to be heard out in the street.

Starret's breathing was distinctly audible over the top of the partition. It was like the breathing of a cross-country runner almost at the end of his wind. It cut off, abruptly. The rap of knuckles on wood came again, then there was a pause and then the knock was repeated.

Starret's shadow moved, dwindled, vanished as he went beyond the source of the light. Doc heard a lock click, a scrape of hinges, a couple of heavy footfalls. The door thudded shut. The lock clicked again.

"What's up?" The low, rumbling voice was unfamiliar. "Why'd you 'phone me to meet you here instead of at the Heron Club?"

"The picture has changed, Jim." By what miracle of self-control Starret had regained the flat, unemotional quality of his speech Doc could not guess. "As I told you, you should have put a bullet into that druggist as well as into the girl."

"And I told you I couldn't get a clear shot at him without going in that store, which would have trapped me. So your ten grand bait has hooked him all right, hey?"

"It brought him around, all right."

"She couldn't have spilled much to him. She didn't know much."

"She said only one word, Triangle, but it was enough to make him smell something phoney about this set-up. He intends to ask the Banking Commission to investigate it."

A low whistle from Jim was followed by a moment's silence. Then, "Intends to, you say. But he hasn't done it yet."

"No."

"So what's your sweat? It'll take that outfit a week before they start to begin to think about asking embarrassing questions. That gives us plenty of time to cash in and cover up."

"It would if it wasn't for the matter I called you about the first time. You thought I was being over careful, having our mail sent to a post office lock box instead of here so that I could look it over before our employees saw it. Well, that little precaution paid dividends tonight. I picked up some letters on my way home, as I usually do. This one was among them. Read it, Jim Gargan. Read it and weep."

PAPER rustled. Then Gargan's voice was reading aloud:

"'In checking the lists of assured under the blanket policy

number so and so, of which your company is the beneficiary, we

find a number of risks in the sum of fifteen hundred dollars

each. Since these are so far out of line with your usual small

coverages, we are regretfully compelled to enclose herewith

formal notice that we are canceling our liability with respect to

the listed risks, effective five days from the date

hereof—' Nice! Perfectly ducky."

"Isn't it?"

"But we've still got five days, haven't we?"

"Have we? Read that next paragraph."

"'However,'" Gargan started reading again, "'we can issue individual term insurance on the lives of these assureds at the same premiums as those under your blanket policy, provided they are able to pass a simple medical examination. In order that we may issue these individual policies before the effective date of this cancellation notice, and so that full protection of your loans shall not lapse, we have instructed our local agent to call upon these assureds at once and have them sign new applications in the requisite amounts—'"

"Do you see, Jim? He'll find out immediately that we've insured for fifteen hundred apiece more than a hundred borrowers to whom we have loaned only twenty-five and fifty dollars. What chance do you think we'd have to collect for their deaths, after that?"

The skin was tight over Doc Turner's cheekbones. He knew now the full enormity of the Triangle Loan Company's apparently legitimate operations, the full horror of the plot Honey Morse had given her life to reveal.

Gargan had absorbed the impact of disaster. "We're washed up. We're all washed up tomorrow morning, soon as that insurance agent starts talking to those suckers."

"If, Jim," Starret's cold voice corrected. "If he starts talking to them. If there's one alive tomorrow morning for him to talk to."

"Got you," Gargan chuckled. "All I've got to do is run home in my flivver and get the stuff, and get it into the gas mains. About a half hour's work at the most and we're in the clear—Hey! Hey, wait. Won't the insurance company want to know how come all the big loans are all in those two houses?"

"They might, but I've already answered that question, in a letter I mailed so that it will be postmarked at seven tonight. We understand, I wrote, their action and approve it, but we feel some explanation is due them. They will notice that all the assureds referred to in their letter of the umpty-umpth live at either Two-twenty-six or Two-twenty-eight Hogbund Lane. These adjoining tenements are in such bad condition that they are about to be condemned by the authorities as hazardous to human life. Their tenants, however, have joined in a cooperative plan to purchase and rehabilitate them and we felt justified, as a contribution to civic betterment, in deviating from our usual limits to make the extraordinarily large loans that will enable them to do so. Does that cover us, or does it not?"

"Like a blanket." Gargan was awed. "If you weren't so crooked, Starret, that you could hide behind a corkscrew, you'd own half the U.S. by now."

One could hear the other's slow, cruel enjoyment in his tone. "I'm doing all right. This little transaction will net us—let's see. Fifteen hundred times a hundred and six is a hundred and fifty-nine thousand, less about thirty-five hundred we've actually loaned out that hasn't come back yet—say a hundred and fifty-five thousand, even, allowing for expenses. And we'll still have a nice little going business that will pay off our investment and a profit—Oh, by the way, there's a little job you have to attend to before you leave here."

"Yeah? What?"

"The druggist. Turner. We can't afford to have him running around loose—especially after what he's heard the last few minutes."

"The last—" Gargan vented a blistering oath. "What do you mean? Where is he?"

"Behind that partition, Jim, probably quite conscious by now. All you have to do is take him out with you—"

"All I've got to—Nix, Starret. Guess again. You don't put that over on me. I'm taking care of blasting the houses because I know how and you don't, and I bumped your gal because she'd have spotted you tailing her, but this nosenheimer's your headache."

"Listen, Jim." Starret was breathing hard again. "Listen. I can't quite—"

"The hell you can't," the other man snarled. "That druggist's your headache, and you're going to take care of him, or—Well, there will be no or else, because I'm going out to do my job now and if you muff yours, you'll burn in the same chair I do. Okay, mister. You've got half an hour!"

Retreating footfalls pounded across the floor. The door opened, slammed shut. The lock clicked.

FOSTER STARRET was breathing hard. His shadow was growing

on the frosted glass, black, menacing. The door in the partition

was opening and he was entering the little inner office, and his

hand was bringing an automatic out from under the flap of his

beautifully fitted dinner coat.

Through the open door Doc could see into the bigger room. He saw a couple of desks, smaller than the one in here, behind a railing that ran the length of the room to windows that had black shades drawn tightly down. The light came from a shaded lamp on the farther desk and by its luminance Doc could make out, beyond the railing, the door to the public hall. Starret was standing over him. Starret's face was no longer an imperturbable mask. Muscles writhed, like tiny snakes, under skin shaved so close it was pink and soft as a babe's. Thin lips were pressed tight, as though to repress nausea.

Here was a man who could plan wholesale murder, coldly, with the calm precision of an engineer drafting a bridge, but who was terrified at the prospect of having to carry his plans into action. He would, though. He had to. Unless... "You're going to kill a hundred and six families, Starret," Doc reminded him, "not only men and women but children." Horror had drained his voice of emotion. "Those who don't die in the explosion will burn to death, screaming. You'll hear those screams, waking, sleeping, the rest of your life."

Hysteria jittered in Starret's eyes, but when he spoke, he once more contrived to speak with sneering calm. "Wrong. I'll hear music and the pop of champagne corks and the soft laughter of beautiful women and the roar of speeding motors. But you—"

"You'll go mad," Doc broke in. "Hearing those screams, you'll go mad. You've still got time to save yourself. You still can stop Gargan—"

"No!" Starret grunted hoarsely, and the old man knew he'd lost. "Put your head down." The automatic was clubbed in Starret's hand. "Put it down so I can stun—"

He whirled to a sharp sound, the click of a key in a lock. The outer door was opening.

A young man stepped through, top-coated, blonde, sleepy-eyed. He turned to the sound of Starret's breathing. "Mr. Chase!" he exclaimed. "You—I—I was coming home from a party and I remembered some work I wanted to finish—"

Starret's gun pounded. The look of surprise was still on Dick Barton's face as he folded over the railing.

Foster Starret turned back to Doc. "That changes things," he panted. His eyes were slitted. They were the eyes of a slavering, hunted wolf. "It makes things easier." He shoved in between Doc's chair and the desk, bent to a drawer. "There's another gun in here—I'll open the safe." He was working it out aloud. "Barton came up here, found you at it. You shot at each other and both shots found their mark."

The drawer screeched open but Doc's right wrist broke free at last of the cords he'd frayed by patient, silent swinging of the swivel chair back and forth, back and forth, while he held them against the desk's edge. His wrist broke free and his fist struck at the spot just under Starret's ear where a man can most easily be stunned.

In the same instant Starret's head jerked up and the fist missed. Starret swung to the footfalls that had startled him, and Jack Ransom was vaulting the rail, mouth open to a shout.

The automatic leaped up, barked, but Doc's frantic grab at it deflected its aim. "Down, Jack," he yelled, "behind a desk," and went over himself, in the chair to which he was still lashed by one wrist.

The gun pounded again and Doc heard a heavy body thud to the floor and saw Starret's gun skitter to the partition. He got his wrist free, and came to his feet, and Starret lay at the base of the desk, his face black—literally black and glistening.

Beside him lay the heavy glass inkwell that had struck him on the forehead, hurled by the best speedball pitcher the Morris Street Tigers ever had!

But there was no sound from the outer office, and when Doc got to the partition door, he saw Jack a crumpled heap on the floor, blood matting his carrot-hued hair.

He wasn't dead. His pulse was strong under the old man's trembling fingertips. The wound cut his scalp deeply, but the bullet had only slightly scraped the bone.

Relieved breath hissed between Doc's teeth and then, as he straightened, he saw the clock on the desk and remembered a rumbling warning: "You've got a half hour!" How much of the half hour was gone? Too much!

Starret was livid, breathing, stertorously. He would not recover from that wound in his forehead in time to do any more damage tonight—if ever.

The heart of the Sahara Desert can be no more empty of human life than a slum street at four in the morning. The little old man in the rumpled tuxedo met no policeman, no one at all, as he ran towards Hogbund Lane.

The tenement-lined gut was also empty, but in front of Two-twenty-six a battered sedan stood, its motor turning over.

Doc's feet made no sound on the broken stone steps that took him down to the cellar of that drab and unlighted structure. He went into dense blackness, paused and listened.

Somewhere far back there was a clink of metal on metal, a smothered oath.

He started towards the sounds, cautiously, straining to see and seeing nothing. The clink of metal came again and then a hiss, and the smell of gas drifted to his flared nostrils. Doc tried to hurry—and crashed into the coal-pile. The noise seemed thunderous!

He went down into the coal, and abruptly there was light on him, a flash-beam. He floundered to rise and the light went out. A form blacker than black loomed over him.

Bruising fingers grabbed his shoulder. He shouted, pulled away, floundered again, the coals rolling under his frantic feet. A blow numbed his arm. He went down with a whistle of expelled breath, groaned and lay still.

Somewhere there were questioning shouts, the sound of opening doors, but Jim Gargan's footfalls pounded across the cellar, towards the dimly pale oblong that was its entrance. A burly figure was silhouetted against that pallor. Then wood cracked—the scantling Doc had thoughtfully leaned across that door for a trap, as he had entered.

Gargan was tripped, but he shoved up again as yellow light laid itself down a slant of wooden stairs from the hallway. Doc reached him, snatched at the muscular figure, flailed futile fists at it.

"Vot iss?" A sleepy, frightened voice called. "Vot iss going on down dere?"

"Help," Doc yelled. "Abe Ginsberg—help me!" and went down under a sledgehammer blow. He grabbed an ankle and was kicked away, but somehow he knew, as darkness welled up into his brain, that the night-shirted janitor had arrived in time...

"IT WAS easy enough for Starret to raise the amounts on

the notes and insurance papers," Doc Turner explained. "The

explosion that would have wrecked the two tenements would have

been ascribed to faulty plumbing and what evidence to the

contrary there might have been would have been destroyed by fire

from the ignited gas."

"Yeah," Jack Ransom agreed, soberly. "There was a tenement downtown blew up that way last year. There wasn't a soul left alive in it."

"That obviously is where Starret got his idea. Those two buildings suited his purpose exactly. They are, as a matter of fact, about to be condemned and it happens that they were built together, so that the same system of gas mains serves both."

"How'd you ever manage to catch on to the scheme?"

Doc rubbed an acid-stained thumb on the counter. "I didn't. Not really. All I had to go on was my tenuous suspicion of the loan company, and the notion that Honey could have been sent to me only by something that she'd overheard from Starret or while with him. That's why I went to the Heron Club to talk to him. If he were innocent, he might be able to help me trace the girl's source of information. If he were guilty, I might chivvy him into an overt act that would betray him."

"You took an awful chance, Doc, tackling him alone."

The faded old eyes twinkled. "I knew I wouldn't be alone, Jack. I knew you would guess what I was up to when I sent you to rent a tuxedo for me, and would be right on my heels. You didn't think I recognized you, hunched down in the driver's seat of Moran's cab, but I did."

The youth's grin was rueful. "I fell down on the job, Doc. I hung around outside, watching, but when you came out, Starret's big car got away from that damn rattletrap of a hack. Gees, was I paralyzed then. The only thing I could think of doing was to rout out Dick Barton and get him to let me into the Loan Company office with his key, on the off chance I might find something in the manager's desk that would hitch up to Starret and maybe help me learn where he could have taken you. Which was no favor to Dick. He would have been killed if the bullet hadn't struck that medal he always carries in his pocket."

"The medal he won in school, for outstanding character," Andrew Turner nodded. "Strange how threads spun in one's early days govern the fabric of one's whole life. I wonder," he mused. "I wonder if Honey Morse knows that her mother and her brothers and sisters live on the second floor of one of those two buildings she saved..."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.