RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

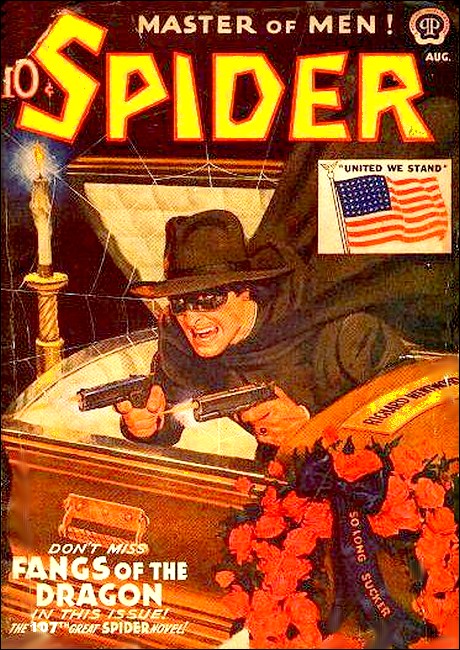

The Spider, August 1942, with "Death Goes to a Picnic"

When Jack Ransom became relief driver for the slum children's annual picnic, he didn't know that Madam Death was leading him... or that old Doc Turner, his partner in crime-fighting, would also be trapped in a new and insidious net drawing tight about the helpless, innocent folks of Morris Street!

THE station wagon was crowded with chattering children. They were wide-eyed to perceive a sky not circumscribed by tenement roofs, or grass not marked Keep Off. The narrow, dirt road ran along the base of a daisy-studded hill and in a lush pasture to the right a herd of cows grazed.

"One's white, Frankie!" exclaimed Becky Aaronson, who was eight and small for her age. "It's all white. Gee, I didn't know there was white cows."

"'Course dere's white cows, stupid." Frankie Lynch was supercilious with the worldly wisdom of his ten years. "Dey're de ones dat give cream."

Up front, Jack Ransom grinned. "Ain't that rich, Mrs. Morton?"

Hair the lustrous blue-black of midnight showed through the open crown of the cart-wheel straw hat worn by the silent woman beside him. The brim hid her face.

"But then," Jack went on, "you got to figure those poor kids wouldn't know cows was anything besides pictures on milk wagons, if it wasn't for these picnics the Morris Street Settlement runs each year."

The woman made no more response to that than she had to the other remarks he'd addressed to her during the past twenty miles or so. He shrugged, his blunt-jawed, youthful countenance sobering. "Say. You sure you told me the right turn off the Parkway, back there?"

"Of course I am." Her voice was deep, vibrant. "Very sure." Her hands were thrust into the pockets of her beige polo coat. Her legs, in dark green slacks, were long and slim. On her slender feet she wore mannish brogues. Ransom had not yet seen her face clearly. "Do you think if I weren't certain I knew the route, I should have asked you to stop no matter how important my 'phone call was?"

Ransom slowed for a curve. "No. I don't guess you would have." But he was still uneasy. That stop had separated them from the two big buses they'd been following and there were no wheel tracks in the dusty surface of this lonely road. "How much farther is it?"

"Not far."

The curve took them around the hill, into woods that suddenly spilled down the slope. A rustic sign on the right said:

YOU ARE NOW ENTERING THE STATE FOREST

and something about being careful of fires. Jack thrust fingers through the carrot thatch of his hair. "I dunno, ma'am. Either we're going wrong or the buses did. Their big double tires would have left marks on this road."

He took his foot off the gas, and put it on the brake pedal. "I'm going to stop and see if I can find the farmer who owns those cows and ask—"

"No," Mrs. Morton broke in, so low that the Pavlich twins on the seat beyond her did not hear. "You're driving on." Her left hand, still in her pocket, pressed something hard against his ribs. "Unless you'd rather stop here permanently."

Skin tightened over the youth's cheekbones, but he grinned tautly. "If that's supposed to be a joke, it ain't funny."

The thing pressed harder. "Take your hands from that wheel and you will learn it is no joke. Drive faster, please. We are already a little late."

"Late for what?"

No answer.

If he started anything, Jack realized, one of the kids was sure to get hurt. There was nothing for him to do but obey.

The speedometer crept up to thirty-five, stayed there at the woman's low command. The forest got thicker. Its boughs met overhead and they were boring through a tunnel of greenish gloom. In back, Tony Scanto started singing Chattanooga Choo- Choo. The others joined in. The shrill chorus covered Jack's words: "What's the big idea? What are you up to?"

The only response was a little chuckle at the back of the woman's throat.

The road was curving again and Ransom couldn't see more than five feet ahead. The trees that blocked his view opened out. He leaned forward and stared through the windshield.

What had come into view, ahead there, became a little more distinct. Jack's neck cords tautened and abruptly he found it hard to breathe.

IF Jan Marvich hadn't sprained his ankle, this morning,

slipping on an oil slick on the floor of the Hogbund Lane Garage,

Jack would have been back there working on Lou Gadsby's

carburetor instead of here fighting sudden, dry-mouth panic which

seized him.

No one, of course, had had any other thought than to summon Andrew Turner from his ancient pharmacy on the Morris Street corner to give Marvich first aid.

"Fix me up quick," the dark, burly man demanded. "I got to have my bus at the Settlement eight o'clock sharp or—" he caught himself, oddly, then went on, "or there's a bunch of brats won't get to the picnic."

The white-maned old druggist glanced at him, his faded blue eyes puzzled for an instant, then suddenly blank. He bent to the ankle, probed it. "Hmm. I can strap this so as to relieve your pain, but you won't be able to do any driving today."

"Nix, Doc! Nix." Marvich looked as if someone had clouted him. "You got to do better'n that. I—you don't want them kids to stay home, do you?"

"N-o-o-o." Acid-stained, bony fingers deftly strapped adhesive around the swelling joint. "But I don't want to see you laid up for weeks, either." Turner patted the last piece of tape into place. "I may be wrong, however. Try putting your weight on that foot."

The fellow struggled up from the chair into which he had been lifted, dropped down again, heavily. "Cripes!" he groaned.

Doc's bushy mustache moved in a thin smile. "You see?" he murmured. "But this doesn't really have to deprive those children of their holiday. Someone else can drive your station wagon for you. How about you, Jack?"

"Glad to, Doc, if Mr. Carson'll give me the day off."

That was all right with the garage owner, but Marvich objected. "Nothing doing. Nobody but me monkeys with that bus."

Turner's blue-veined nostrils flared. "Jack's as good a driver as you can ever hope to be, and you know it. What's behind this, Marvich? Just now you were upset about the children's being disappointed, now you're putting unreasonable obstacles in the way of avoiding it?"

"Hell," Ransom grunted. "He was just making a phony play to the gallery."

Marvich glowered at them, swallowed. "I got to 'phone someone." He twisted, pulled himself up by the back of the chair. Jack grabbed his arm to help him but he jerked it away, growling, "Leggo. I can make it," and started hopping toward the booth at the rear.

A truck honked from the portable gas pump out by the curb and Carson hurried to it. Ransom turned to the old druggist and asked, very low, "What's eating you, Doc?"

Shaggy eyebrows arched. "Eating me? What gives you the idea anything is?"

"Look," the youth grinned. "You can't pull that stuff on me." They were two generations apart in years, but the stalwart mechanic and the old pharmacist so often had fought shoulder to shoulder against the crooks who would prey on the friendless poor of Morris Street that there was an almost telepathic bond between them. "You've got a hunch the guy's up to no good."

"That's all it is, son," Turner yielded. "A hunch. Reasonless, except that it seems out of character for that sullen brute to be so concerned about a few children. After all, we know almost nothing about him."

What Doc meant was that in a neighborhood whose common poverty knit lives as closely as those of a small country town, this in itself was suspicious. "He took a furnished room on Morris Street about three months ago," he went on. "He has made no friends and has no regular employment, but he seems always well supplied with money."

"And how!" Jack said. "He even paid cash for that used station wagon, three-fifty on the nail. He got a bus license for it, so's he can buy all the gas he needs, but he only takes it out a couple times a week. Come to think of it, that's most always at night and from what the washer says, he stays out pretty near all night with it, uses up plenty mileage. Which looks phony all right, but I still can't figure what he could possibly pull on this picnic."

"Neither can I. But—"

The booth door rolled open and Marvich growled, "Okay, Ransom. You can take it out."

"—but I'm going to be a lot more comfortable," Doc Turner finished his sentence, "knowing that you are driving those youngsters." An impish twinkle had come into his tired old eyes. "Which," he had added softly, "is why I strapped our friend's ankle so that he can't stand on it."

THAT had seemed only a cute trick then, and ninety-nine

to one uncalled for. Now, with a gun digging Jack's ribs and

those three shadowy figures waiting in the shadows of the road

ahead, he knew that Doc's hunch had not gone far enough. "Slow

down," Mrs. Morton whispered. "And be very careful what you

say."

The middle one of the three men flung his hand up in an imperative signal to stop. The other two held rifles aslant their bellies in a manner that showed they were quite ready to use them. All three wore grayish green.

Behind Jack the children stopped singing. The abrupt, throbbing silence emphasized the ominous loneliness of the forest. In these gloomy depths a shot would not be likely to be heard.

THE Indian summer morning was hot, but Jack Ransom was chilled

to the very marrow of his bones. Marvich had told him to park in

the side street, around the corner from the Settlement. He had

done so, had gotten out to look for the woman he was supposed to

meet—Mrs. Morton.

On Morris Street one great sightseeing bus, bedecked with banners, was already jammed full of cheering youngsters. The sidewalk swirled with excited small fry whose no less excited mommas wiped noses and jabbered last minute injunctions in half the dialects of Europe. A harried little man stood by a second bus loudly calling names from a rumpled list, and flustered committeewomen darted frantically about searching for their charges.

"Gawd," Jack groaned. "Look what I've gone and let myself in for." And then he saw the tall woman moving quietly toward him, trailing a double line of happy but decorous youngsters. He sighed with relief and smiled at her. "You're Mrs. Morton, I hope."

"I am." She didn't look up. "I presume you are the young man who is taking Mr. Marvich's place."

"Correct. My name's Jack Ransom and I'm glad it's you riding with me instead of one of those society dames running around like hens with their heads chopped off."

She laughed, throatily, and began loading her brood into the station wagon. Seeing that she needed no help, Jack had taken his place under the steering wheel. "I don't remember seeing you around here before," he'd remarked when she slid in beside him. "You're a lot different from these other do-gooders."

"Am I?" There had been a note of finality in her response that had choked off further amenities. She had not spoken again until she'd asked him to stop at a roadside gas station so she could telephone an important message she'd forgotten. Of course, now he knew she had merely side-tracked him so that she could separate the station wagon from the buses, and lead it to this ambush.

As Jack neared them, the two armed men started into motion with an odd, military precision. "Stop!" Mrs. Morton ordered. When Jack had braked, one of the riflemen was at each front door of the car.

They peered in, their faces still as masks. But they were not really in uniform. They wore hunting costumes, complete with peaked cloth caps. This was rescue, not menace. Somehow they'd gotten wind of whatever Mrs. Morton was up to, and had intervened in time.

Jack relaxed but said nothing. The woman's gun muzzle still bored his ribs. No use taking chances with it.

The third man jerked open the right-hand door, his lips tight in a narrow, sardonic countenance. "I've had to change our plans a little, Mona." Their plans! So they were not rescuers—but allies of Mrs. Morton! "Instead of going around by the trail, you'll have to take them up through the woods from here."

"It's a stiff climb, Gurt." The woman's gun left Jack's side but hard, expressionless eyes watched him through the open window and the rifle snouted point-blank at his skull. "I wonder if the littlest ones can make it."

"They had better," the man called Gurt said grimly. "Get them started."

THE woman rose and turned, one knee on the seat, her

hands gripping the top of its back. "I have a wonderful surprise

for you, children." Her face, Jack saw for the first time, was

triangular and small-featured, with a voluptuous mouth scarlet

against dusky skin. "Instead of the picnic, Mr. Gurlock's going

to give us a venison barbecue on his estate."

The other kids just stared, but Becky Aaronson held up a small hand. "Yes, honey," Mona Morton asked. "What is it?"

"What's a ven—venis—what you said?"

"Deer meat, sweetheart. Roasted whole, over a slow fire. It's a great delicacy."

The child's tiny nose crinkled. "I don't like delicatessen."

"They're gonna have ice cream at the picnic," the blonde Jennsen boy said.

"An' soda pop," Frank Lynch added. "Coco-cream an' strawberry. I saw dem put de boxes on de bus."

"You're wasting time, Mona," Gurlock rasped. "Get moving quickly, or—"

"Please, Gurt," Mrs. Morton broke in. "You're only frightening them." Jack had a queer feeling that she herself was terrified. "Listen, sweetheart, Mr. Gurlock has ice cream for us too, and soda and—and chocolate cake."

"I don't like him," Becky said flatly. "I don't want to go to no 'state. I want to go to the picnic. Frankie! Tell her we want to go to the picnic."

"Aw, nuts." Masculinely, the boy had suddenly gotten bored with the argument. "What's the diff where we go?" He started to scramble out and Mrs. Morton, sighing with relief, turned and pushed past the Pavlich twins and swung lithely to the ground.

She helped the two round-faced little Poles out, went back to lift down a couple of toddlers whose names Jack didn't know. Karl Jennsen climbed out, and Sonia Maslavsky; then it was Becky's turn.

She settled down in her seat and refused to move.

"Please don't be stubborn, honey." Definitely there was strain in Mona Morton's voice. "Please be a good little girl and stop spoiling everyone's fun."

"No."

Gurlock grunted, pushed the woman aside and reached in. "Come out of there, you little brat." His fingers clutched the child's pipestem arm. She screamed. Black wrath leaped into Jack's brain but the rifle barrel that jabbed through the window beside him kept him frozen. Becky caught at the door frame and screamed again.

Frankie Lynch yelled, "Leggo! You're hurtin' her." He jumped for Gurlock, his little fists banging at the man's shoulder.

The armed guard on that side grabbed for him, but Gurlock's knuckles chunked on the boy's head, sent him flying off the road.

Frankie fell into high underbrush, out of sight. Becky's cries cut short and in the ensuing silence Mona Morton moaned, "No, Gurt. No!"

There was a commotion in the underbrush, and a stone sailed out. It struck Gurlock's cheek. The guard cursed. Frankie popped up in the brush, scuttled toward the concealment of the thicker woods.

"Stop him!" Gurlock snapped. The guard's rifle jumped to his shoulder!

Jack Ransom hurtled through the open door and slashed at the gun—a split-second after it cracked. He had an instant's vision of flame-jet stabbing at a small scuttering figure. Then red-hot steel streaked his own scalp and the world exploded into oblivion.

DUSK, sifting leaden through the "El" trestle that roofed

Morris Street, failed to darken the cobble-paved gutter between

drab tenements. Under hanging lights, the pushcarts lining the

curbs were heaped with glowing color; the orange, green and

scarlet of fruits and vegetables; the silver of fish fresh from

the seines.

Before the doorway of his drowsing drugstore, Doc Turner peered up the familiar street, his seamed brow puckered with an anxiety he tried to tell himself was reasonless.

Countless Saturday evenings he had stood like this, watching the polyglot, chattering crowd that jostled past, smiling greetings at these people whom he'd served more years than he cared to recall. Now a subtle change had come over the throng. The hucksters' raucous cries had a new zest, the shawled housewives bargained less shrewdly, no longer avid to squeeze the last possible bit of value out of every penny.

Money was comparatively free on Morris Street. The factories along the river were running full blast, and every man who was willing and able to work had a job at undreamed-of wages.

Doc had a special smile for the youths who strolled by, clad in army o.d. or flapping navy blues. Proud was his smile—and a little sad. Such a little while ago they'd been grimy small boys going off in the Settlement buses for a day's picnic in the country.

Where were those buses—and the station wagon he had watched follow them this morning? The uneasiness that had nagged him all day wouldn't be stilled until Jack Ransom returned safely.

The old man snorted, vexed with himself. What could possibly happen to Jack? Even if some emergency did arise, the boy was amply able to take care of himself—and the children. True enough, he'd been turned down when he'd tried to enlist in the navy because of a heart that unsuspectedly had a murmur; but that was bosh and poppycock. If the fool doctors who'd rejected him had ever seen Jack in a scrap—Ahhh! There they came, motors thundering under the dark canopy of the "El".

The first bus roared by, its bunting bedraggled, the youthful passengers silent, worn out with their long day. Now the second, and behind it...

Only a small truck piled high with slatted crates of live chickens. An olive green touring car with army plates followed it, then another truck. Behind this, for blocks, the street was empty of traffic.

Doc's thumb, spatulate with rolling thousands of pills, rubbed the scarred frame of his show window. There was nothing to get worried about. That second-hand station wagon couldn't be expected to keep up with the powerful buses. It would be along soon.

But ten minutes passed, fifteen, and it didn't show up.

The street lamps came on, shadowing the lines that deepened around Doc Turner's craggy nose. He sighed, went back into the unlighted store, its ponderous showcases ghostly in the dimness. He dropped a nickel in a 'phone slot, dialed the Settlement's number.

They took infernally long to answer, but did so at last. Yes, the picnickers were back. The buses were all unloaded. "How about the station wagon?"

"What station wagon?"

"Jan Marvich's. The one you hired to take the overflow."

"Look, mister," the voice in Doc's ear was petulant with fatigue. "I don't know anyone called Marvich. We didn't hire any station wagon. We took as many children as there was room for in the two buses we did hire, and those who applied late didn't get to go. I've checked my list of those who did go, and they're all back. If yours aren't home, they must be hanging around the neighborhood some place."

Doc hung up and came out of the booth. He shambled slowly to the partition at the rear of the store, went on through the green curtain hanging there. When he came out again he had on a shabby topcoat, a battered felt hat, and he was bowed under a weight heavier than his years. He shuffled to the street door, closed and locked it.

He had more pressing business this Saturday night than tending counter.

The buses were gone from in front of the Settlement House. The musty old building was hushed in the interlude before the slum's teenagers would arrive for their dances and club meetings, but the harassed little Secretary was in his office.

"The applications for the picnic," Doc said. "Did you handle them yourself, Mr. Corbin?"

Corbin blinked at him. "Why, no. One of my volunteer aides, Mrs. —— She's new, hadn't been assigned to any regular activity yet, and so I asked her to—Oh dear! What is her name?"

"Mrs. Morton," the druggist told him.

"That's it! Mrs. Mona Morton. How did you know?"

"I happen to have heard her mentioned, this morning." Jan Marvich had mentioned the name, when he was giving Jack Ransom his instructions. "You say she's a new worker?"

"Yes. She's been helping us only a week but she took hold right away, didn't bother me at all till she was ready to hand me the completed list of the children who were to go. I only wish we had more like—"

"Did she happen also to give you a list of the late applicants?"

"Yes indeed. I asked for it so that I could make sure they're taken care of first next year." Corbin shuffled among the clutter of papers on his desk, pulled one out. "Here it is. I haven't had time to file—"

"Ah, yes." Turner plucked it from his fingers, scanned it. "Mmm. I wonder if you can give me Mrs. Morton's address."

"Certainly." The other opened a small metal file box, pawed through the three-by-five index cards it contained. "But I don't understand, Mr. Turner. Why are you so interest— Hello! This is strange!"

"That her card isn't there?" Doc murmured, his face bleak. "No. I should have been surprised if it were, or being there, if the address had been correct. Thank you."

Out of the office before the befuddled Corbin assimilated this last startling statement, the pharmacist took the list of belated applicants with him. Presumably belated. He had a shrewd suspicion that most of the children named on it had applied in plenty of time to have found places in the two buses.

Doc Turner berated himself for a blundering fool. If only he had followed through his 'hunch' of the morning—but he had not, and as a result he'd sent Jack into some still unguessed peril, and with him—nearly a score of little children!

Where were they? What had happened to them?

AT that moment, some fifty miles from Morris Street, Jack

Ransom was asking himself the same questions. He had no idea how

long he'd weltered in a disjointed semi-awareness into which

sounds and sensations penetrated but had no meaning. At the

beginning there had been pain, numbing agony that rayed from a

hub at the top of his head.

The pain was still with him, duller, throbbing.

Through the pain, that first time he'd half-awakened, had come realization that he was being carried upon a joggling shoulder. There had been a threshing of brush all about him and little whimpers. Then something jolted him and he'd slid down and down into sick blackness.

The next time there'd been a harsh voice, commanding, and someone had been doing something to his legs. There had been other moments of blurred waking. He couldn't bring them back clearly, but he knew that each time he'd approached consciousness a leaden weight of horror had oppressed him.

Now, quite suddenly, Jack knew why and it struck him fully awake. He recalled a jet of orange-red flame—and a small boy slain as one snaps a shot at a rabbit.

That must have been a long time ago. It hadn't been noon yet when Frankie Lynch was murdered, but darkness met Jack Ransom's eyes when he forced them open. In the darkness, a single bright star blinked at him. He saw it through a broken window. He lay on the floor of an utterly bare room. Its cracked walls became dimly visible and the rectangle of a door was outlined by a thread of light.

There were sounds behind that door—the dry, racking sobs of a child who no longer has strength to weep. "Stop that," a man's voice rasped. "Stop that damned sniveling."

The sobs cut off, but now Jack made out many small noises: the thump of a restless foot; the rub of fabric against a wall; a hacking cough quickly stilled; little sounds that served only to emphasize an atmosphere of fear.

The kids were in there. They were under guard. But Jack had been dumped in here, too nearly dead to require guarding. Or so his captors thought.

Jack wasn't dead by a long shot. There was the window over him and the woods outside—he could hear its dark rustle. He would crawl out and run for help. The only difficulty was that they had taken the precaution of tying him hand and foot. That was all right. The glass splinters sticking out of that window frame had sharp edges.

Jack wasn't thinking very clearly yet. If he had been, he would have known it was impossible for a man lashed as he was, weakened by blood lost from a four-inch bullet gash in his scalp, to reach that window. But, with the blind courage of ignorance, he managed it.

The floor rose and fell like the deck of a ship at sea, but he dragged himself up to the window, hung by his elbows to the sill and breathed in the cool, balsam-laden air. The whirling inside his skull slowed and his eyes cleared. Not far away the forest rustled in the gentle night breeze. Nearer, not five feet from him, a black form turned to the house. Starlight glinted on a rifle barrel.

In the next instant, Jack Ransom knew that his face had been detected.

IN the stuffy kitchen-living room of a tenement on Morris

Street, Doc Turner stared blankly at a woman whose work-gnarled

fingers nervously twisted a child's sweater.

"I don't believe you, Tanya Maslavsky," Doc was saying. "You would never send Sonia all the way downtown alone after dark."

The mother's red-rimmed eyes were miserable, but she shrugged and said, "Can I help if by her grandma she wants to come and visit?"

"That's your story, eh, and you're going to stick to it." That had been the Scantos' story too, only in their case, little Tony had been visiting an uncle over the weekend. "I see." And Rivkah Aaronson had said that her Becky was on an overnight hike with the Girl Scouts. "Where's your husband, Pavel?"

"Overtime he works tonight." But her glance flicked to the shut bedroom door in a side wall. "By de factory."

"He's a foreman in the old Atlas Sewing Machine Works, isn't he?"

"Da!" Yes.

Vito Scanto ran a lathe in that same plant, and Abe Aaronson was a toolsetter. From the Settlement Doc had gone first to Jan Marvich's rented room, but Marvich's landlady said Marvich had left that afternoon with a strange man, and had not returned. It added up to a significant total...

"Just one more question, Tanya. What is Pavel supposed to tell them to bring little Sonia home alive and unharmed?"

The mother's mouth opened but no sound came from it. Then stark terror flared into her face as someone said harshly, "That is one question too many for your own good." The bedroom door opened and a man stepped through, a thin smile on his narrow face, a stub-nosed automatic in his fist. "It makes up my mind for me."

Behind him a woman called, "Not here, Gurt." Her voice was deep, vibrant. "These walls are thin. You'll bring the house down around us like a nest of hornets."

Gurt Gurlock snarled, "I'm not a fool, Mona." His black eyes were gimlets boring into the old pharmacist's brain. "You are as persistent, old man, as that Polack in there is stubborn. Perhaps a little ride in the country will cure you both." His look shifted to Tanya Maslavsky. "Get your husband's street clothing, you, and your own."

THE rifle's steel-shod butt pounded Jack Ransom down from

the window, glass showering about him. "Schweinehund!" he

heard, through the thudding agony. "Pig dog! I teach you!" Hinges

screamed and yellow light lay across him.

"Was ist los?" growled the man he'd heard silencing the sobbing child. "What goes on?"

"Our prisoner, Otto. He came alive. Luckily, I heard him at the window... Leutnant Gurlock should have let me finish him down by the road. If it had not been for that Mona Schwartzkopf—I tell you, for this business a woman is too soft."

"No, Carl. She is hard enough, she was right. That fisherman on the bridge, because of whom we took our guests to this abandoned hovel, might have been alarmed by another shot so close after the first two."

"My knife would have been silent. Why not use it now?"

"Because our orders are to do nothing needless till the Leutnant returns." Jack could make out the one called Otto, a burly silhouette against yellow luminance. "Or until he does not return by midnight. You would not disobey, would you?"

"Of course not, but this American pig might make trouble."

"Leave him to me." As Otto moved in he vacated the doorway and through it Jack saw a lantern on the floor of another room, larger than this but just as bare of furnishings. At its other end he saw an archway of paintless wooden pillars, framing the double panels of an outer door. On the floor of that room, lined up against the walls, were huddled the children who'd sung so happily on the forest road.

The smallest youngsters were asleep. They were the lucky ones. For a while at least they were spared the terror which showed in the pinched faces of their older companions.

But why—A brutal toe crashed blackness once more into Jack Ransom's skull!

A FAMILIAR voice was calling him. "Jack." Doc Turner's

voice. "Wake up, Jack." There was urgency and deep concern in the

voice.

"Jus'a minute, Doc," Jack mumbled, trying to unglue his eyelids. "Gosh, I'm glad you woke me. I been havin' the damnedest nightmare—" His eyes opened and he gasped. It was no nightmare.

Doc was here all right, but he was tied to one of the uprights of the archway Jack had seen from the other room. And bound to the other pillar was a heavy-limbed man with a blond brush of hair and the round, large-boned face of a Polack. He was Pavel Maslavsky, Sonia's father. Otto stood between them, rifle slanted across his belly. Nearer Jack was Gurt Gurlock, no longer in his hunter's costume, but still smiling sardonically. The lantern light, striking upward, gave his narrow face a Satanic cast. The children were all awake.

"You've had a tough time of it, Jack," Doc said gently. "How do you feel?"

"Not too good." The youth tried to smile, knew he'd made a miserable failure of it. "How—how'd you get here?"

"I didn't think I should refuse Mr. Gurlock's invitation, the way he put it." Doc nodded at the automatic Gurlock fondled. "He was really quite urgent."

Mona Morton was beside Gurlock, her straw hat exchanged now for a bright-colored handkerchief knotted around her head. They were both looking at something beyond Jack. He rolled his head around. And rolled it away again. No one had a right to look at the agony of the mother who, on her knees, cradled a flaxen- tressed small girl in straining arms and mouthed little, crooning noises.

No one had a right to intrude on that agony, but Gurt Gurlock sneered at it. "A pathetic picture, is it not, Pavel Maslavsky? But you have it in your power to end it by a few simple words."

Beads of cold sweat stood out on the father's corrugated brow. His arms were bound to his sides; his great hands knotted.

"Just a few words," Gurlock said softly, "and a sketch of the mechanism your factory is making for the American Army. It isn't really important, you know. It is only a small part of the airplane locator, and without plans of the rest, it would be worthless to us."

"You must have those plans," Doc observed, "or most of them, or you wouldn't be so anx—" Gurlock's backhand cracked across his mouth.

"Silence. You are lucky to be alive!" He turned back to Malavsky. "Well?"

There was a little blood on Doc's lip and there was silence in the room, and in Pavel Maslavsky's eyes there was torture. "Pavel," his wife moaned. "Please, Pavel. It's our Sonia. Our daughter."

The Pole's thick lips writhed. "Our daughter, Tanya. Yes. But I can't. Not efen for Sonia can I be traitor."

"So," Gurlock purred. "Still stubborn. Well, we shall cure you, Carl!"

Heels clicked in the doorway to the inner room. "Leutnant!"

"Proceed as instructed."

Carl moved in, leaned his rifle in a corner, and went past Jack with a feline swiftness. He bent over the mother and child.

Tanya's scream was a terrible sound.

Carl straightened, the small form dangling from one huge fist, a long, cruel steel blade in the other.

The stanchion to which Pavel was lashed creaked with his lunge, but his bonds held him. "What do you say, Maslavsky?" Gurlock whispered. "Speak!"

From the man's expression, Carl's clasp knife might be twisting in his vitals. The room was abruptly very still.

"No," croaked Maslavsky.

"You will change your mind," Gurt Gurlock said softly, and then even more softly. "Begin, Carl."

The lantern light flashed on Carl's blade as it moved. "No!" Slim fingers caught Carl's wrist and Mona Morton turned to Gurlock, her small features lined, suddenly haggard. "No, Gurt." Her voice was thin, almost shrill. "I won't let you. I can't let you!"

GURLOCK'S eyes were black flame, but otherwise his face

was without expression.

"Pardon me, Mona. I did not hear you rightly. I thought you said that you will not let me do something."

"That is what I said!" Her other hand joined the one on Carl's wrist and both clung desperately. "The boy's death couldn't be helped. You couldn't let him escape, but this—You can not do it!"

"Why this sudden qualm of conscience?"

"I didn't think—I didn't know it would come to anything like this. I was sure the fathers would give in quickly. After all, they are foreigners here."

A small muscle knotted in the man's cheek. "This is no time to discuss psychology, Mona. Carl, you will proceed."

"Ja, Leutnant!" The fellow's wrist wrenched but there was unexpected strength in the slender hands that held it and he was hampered by his burden.

Gurlock grunted, moved to the pair, sank fierce fingers into the woman's arms. "Stand aside!"

"No."

He stiffened and there was a whimper of pain in the back of Mona's throat and her fingers opened—just as Jack's rolling body hit the three pairs of legs hard. The two men and the woman came down atop him, crushingly. Someone shouted; a shot pounded in his ears, oddly muffled, and pain exploded in his skull.

Somewhere in the sick dark a new voice said, "Okay, everybody, hold it." Abruptly all movement stopped and very strangely it seemed to Jack he heard cheers. The cheers of children.

"All right kids," the new voice said. "Less noise, please."

The cheers stopped. Jack got his eyes open. A lean-flanked, gaunt young man was handcuffing Carl to Gurt Gurlock, while a second held Otto by the scruff of the neck. A third was cutting Doc loose. "You were almost too late," the latter was saying. "You would have been if it hadn't been for my young friend there."

"I'm sorry, Mr. Turner." There was an air of quiet authority about the man. "But we had to drop way behind when you turned off the Parkway or they would have noticed us following you. And then we had to climb the hill on foot. In first gear, the noise would have warned them."

Doc's smile was very tired. "The F.B.I. ought to have cars with silent gears, but I suppose I shouldn't complain. After all, you got here in time."

"Not quite, for her." The G-Man glanced toward the floor near Ransom. A slender body lay very still there, and the scarlet that stained her coat had stopped spreading. "How'd she get it?"

"Gurlock's gun must have gone off as they fell, when Jack hit them."

MONA MORTON was dead, and Jack Ransom did not begrudge

her the peace she'd found at last. Weariness welled up in his

brain, a dark flood. He let his eyes close and he must have slept

a little while but he was awakened by a wet cloth swabbing his

face.

"That's better." Andrew Turner smiled down at him. "A lot better."

"Doc. You came through once more, but hanged if I see how you did it."

The old man had a first-aid kit, supplied by the Federal men, and as he tended Jack's wounds he told him about his discovery at the Settlement House. "As soon as I read the names on that list, I suspected what was up. The one thing common to all the children on it was that their fathers worked at Atlas, in jobs that would make them familiar with the part being made there. After I found that someone had come for Marvich and taken him away, I was sure I was right. So I called the F.B.I. and arranged that they trail me as I interviewed the parents."

"Why didn't you let them do that?"

"In the first place, because I knew those people wouldn't talk to Government men. I hoped they would be franker with me. I was wrong."

"Yeah. You ought to know how close-mouthed they get when in trouble."

"Yes," Doc sighed. "I ought to know. We've been up against it before, that heritage from their old way of living when every official was their enemy. Gurlock knew it too, and took advantage of it. Scanto and Aaronson refused to ransom their youngsters by telling him what he was after but he still could depend on their not going to the police, at least long enough for him to finish his list in a search for someone more amenable. My second reason for making the visits myself was that I hoped I'd run into Gurlock somewhere and bluff him into taking me to his hideout, with the G-Men following.

"It was the only way to find and rescue you. The spy would not have talked if he'd been arrested; and obviously, if he failed to show up when expected, whoever he'd left guarding you would have to kill you and the children."

"So you made live bait of yourself."

Doc's gentle smile crossed his seamed old face. "Why not? It was the least I could risk for those who were risking their children. Polacks and Jews, Irish and even Sicilians—they may speak distorted English and be baffled by our strange ways, but they are Americans."

"Yeah, Doc." Jack Ransom grinned. "Americans. That's what Gurlock forgot when he figured it would be easy to make them talk."

Andrew Turner's faded blue eyes were alight. "And that is what Gurlock's mad dog of a leader forgot when he thought it would be easy to divide the hodgepodge of races that is our America, and defeat us through our own differences. That is the mistake that will crush him."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.