RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

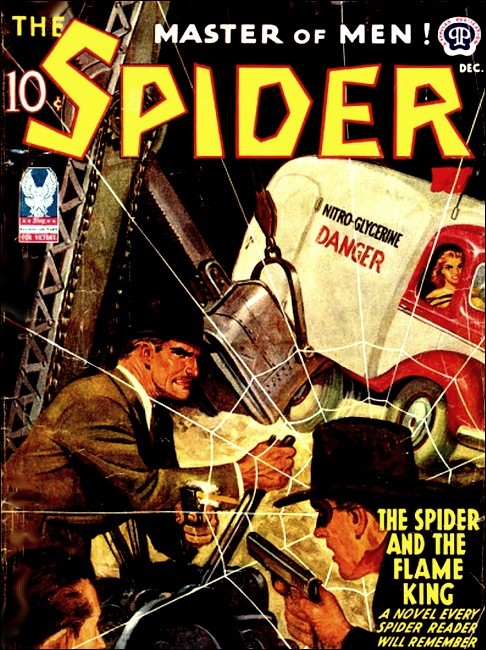

The Spider, December 1942, with "Death with a Dog's Face"

WHEN the war came to Morris Street it was not as the long rhythmic march of boots nor the roll of tanks nor the sense-blotting boom of bombs and the screams of shattered humans. When the war came to the slum dwellers, whom in his ancient pharmacy Andrew Turner had served more years than he cared to recall, it came as a death that struck silently and unseen.

TILL tonight the war had touched Morris Street no more heavily

than any other street along the Eastern Seaboard. There was the

dimout, of course, so that sky-glow should not betray tanker or

transport to the Axis sea-wolves.

"Damn," Jack Ransom groaned, watching a couple of natty marines stroll past the store doorway, where he stood chatting with the old druggist. "I still don't see why they turned me down just 'cause of a leaky pump I didn't know I had. Suppose I did conk out from that instead of a bullet, so what?"

Doc put a thin, veined hand on the youth's muscular arm. "You know the answer to that, son." Little and stooped and feeble-seeming, his silken mane a silver nimbus in the gloom, he contrasted oddly with his barrel-chested, carrot-thatched companion. "You might conk out, as you put it, on sentry-go or when you were key man in some night patrol. Or that heart of yours might go bad and lay you up in a hospital bed needed for the wounded. But why fret? Aren't you doing a job as important as fighting?"

Jack grunted. "Yeah, I suppose I am."

The garage around the corner on Hogbund Lane now housed only the great trucks that served the war factories and, an ace mechanic, Ransom was doing two men's work keeping them rolling on their brutal, twenty-four hour schedules. "You're right, I suppose," he repeated, "but I feel like a lousy slacker anyways. If I could only slap a Jap down, just once—

"Oh, oh. What's got into that bozo?"

Out on the sidewalk a shadowy figure had stopped short, was striking out, frantically, at empty air. By the light of a street lamp bracketed to an "El" pillar, Doc made out that the man's mouth gaped with a soundless scream, that his eyes were black pits of agony... In that same moment he folded down.

Because of the half-light, the swiftness with which it had begun and ended, the utter silence, the incident seemed somehow unreal.

It still seemed unreal. The inanimate gray form did not sprawl on the concrete. It rested on its haunches, back bent, head between crooked knees. Unmoving, it was less a human than a mannequin whose strings had been dropped by the puppeteer.

Only those nearest were as yet aware of what had happened when Doc reached the corpse.

That it was a corpse he already knew as he bent to it. The bulging eyes were dulled stone. The tongue already blackening, curled in the still gaping mouth. Jack was beside the druggist when he straightened up. The freckle-dusted young face was yeasty. "Cripes, Doc," he gagged. "Is that how I'm going to get it?"

Turner stared—understood. "No, boy. It wasn't his heart." Men and women, morbidly curious, were crowding about them now, but they were so busy with questioning one another that none save Ransom heard Doc Turner add, very low. "This is murder."

A policeman bulled his blue bulk through the jam, spied the squatting form. He grabbed a shoulder with a beefy hand. "Get up out uh that you souse—Urrgh!" The body toppled sidewise, sprawled out. Crowd chatter cut off in a hush of horror.

"Yeh," Jack Ransom muttered. "Yeah, Doc. I see what you mean."

A bloodless cut sliced the dead man's neck under the ear, ran around out of sight under the unshaven, ponderous jaw. Out of this slit, like the tail of a mouse diving into its hole, curled an inch-long black filament, oddly stiff.

It wasn't a cut. As Doc's keen eyes had noted, it was the furrow made by a cord buried deep in the flesh, a noose cutting off breath. "But there wasn't anyone near him," Jack protested. "I was looking right at him and I'll swear on a stack of Bibles there was no one near enough to garrot him like that."

"Get back," the cop ordered hoarsely, clearing a space around the cadaver. "Get back, damn—

"Oh! Sorry, Doc." His shoving fists checked. "I didn't see it was you. Look. Will yeh do me a favor an' call the house while I keep this gang uh ghouls under control?"

"Of course, Tim. Glad to help you out."

JACK stood with his back to one of the ponderously framed

showcases, once painted white, that were backgrounded by the

sagging, bottle-laden shelves of the ancient pharmacy. His arms

out either side of him, strong hands gripped the showcase's edge

and his cheeks were sucked in, his look sultry.

"I'll give in it was pretty dark out there," he took up where they'd been interrupted by Flannery. "But the guy was right under the light when he got it. How could I have missed seeing the killer slip the noose around his neck?"

Doc looked at him, smiled bleakly. "Why ask me? The only answer I can give you is one written four centuries ago, by someone far wiser than either of us. 'There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than—'"

"'Are dreamed of in your philosophy.' Yeah." A tiny muscle twitched at the corner of Jack's mouth. "Yeah, Doc. We've seen a lot of queer things happen around here, you and me, some mighty queer things."

"And this," the aged pharmacist murmured, "seems to be one of the queerest."

After a while there were men in the drowsy old drugstore who though not in uniform were unmistakably police. One of these was a little taller than Turner himself, but his lean frame had the gauntness of a bloodhound and the eyes in his bony, expressionless face had the blue-gray hue of tampered steel.

His thin lips barely moved as he asked Doc, "Did you know this Bronko Maslyk?"

"I know most people around here, Captain Jameson. I've known Bronko since he landed in this country, twenty years ago. I helped him find a furnished room to live in, and got him into the English for Foreigners class at the Settlement House."

"What can you tell us about him?"

"He was a hard worker and always was able to find a job."

"Where was he working now?"

"As head porter in the Tracy Department Store." Doc shook his head. "There's no tie up with war work there."

"No. Go on. Who were his contacts around here?"

"None that were not very casual, except possibly myself. He had no friends."

"What I want to know is if he had any enemies."

"I don't see how he could have. He kept himself strictly to himself, even at work. He was a very lonely man."

"Family?" asked the captain.

"None that he ever told me about. None in this country. Bronko is—was—still living in that same room I found for him, twenty years ago, alone except for Marta Sigurd, the old woman who rented it to him. Someone abroad used to write to him though. From Czechoslovakia. The letters were addressed to this store and he would pick them up here."

"Why here?"

"He never explained, and I did not ask him."

"Do you happen to have one of those letters to show us?"

"No. They stopped coming about a year and a half ago. The last one was in a different handwriting and it had French stamps on it. After that there were no more."

"Hmmm." Captain Jameson turned to a detective who'd come up, a tall chap with the hazy look of a man who ought to wear glasses but did not. "Well, Carter?"

"This cord Maslyk was throttled with, skipper. It's not catgut, as you thought. I can't tell you exactly what it is till I've a chance to work on it in the lab, but I've a notion it's a vegetable fibre processed in some unfamiliar way."

"Okay. Find out what it is and give me a report." Carter went away and Jameson beckoned a uniformed sergeant to him. "Tell those reporters outside that I know who the murderer is and expect to arrest him within twenty-four hours."

Doc Turner knew he lied.

IT was only a little after eleven when the police cleared

out and left the druggist and his carrot-topped young friend

alone together. Doc yawned. "There won't be any more customers

coming in tonight. I might as well close up."

"Which would make the first time you've locked your door before midnight without a damn good reason," Jack grinned.

The faded blue eyes twinkled. "No use trying to fool you, is there?"

"Nope. No use at all. Spill it."

"There's nothing to spill except that I think I'll go and have a little chat with Marta Sigurd, Bronko's landlady. Jameson's men have cross-examined her, naturally, but I might get something out of her she doesn't even know she knows."

"Or knows and wouldn't tell them. Yeah. But ain't it kind of late? The Norski needs her sleep, she's older'n the hills."

"Which is why she doesn't need much sleep." The pharmacist's smile was a little wistful. "When the hours left to you are very few, my boy, they become too precious to let slip away in the night. However, I'll look up from the street and if her window isn't lighted I won't go up."

"We won't go up," the youth corrected. "I'm coming along."

He was mistaken. As he waited for Doc to lock the store door, he heard his name panted, "Jack!" and turned to a boy in grease-blackened overalls who trotted toward him from the corner. "Gees, Jack. The boss figured I'd find yuh here."

"Swell brainwork," Jack said, disconsolately, "seeing I told him I'd drop in on Doc. Well, what's the grief?"

"That big truck—you know, that ten tonner uh Dan Corbett's—was just towed in with a cracked cylinder block. They need her by seven a.m. to rush a mess of Bren-gun mounts to the Norfolk Navy Yard."

Ransom pulled the edge of his hand across under his nose. "Okay, Danny. I guess I'm in for it. 'Night, Doc."

"Good-night, son."

The old druggist watched Jack and the grease monkey go around into Hogbund Lane, turned and plodded wearily in the opposite direction. Morris Street was deserted now, desolate under the "El's" black-barred roof. One street lamp to each block burned feebly and the storefronts were darkened. The street seemed filled with silent, ominous shadows that withdrew into nothingness as Doc neared them, peered forth again when he had passed.

He crossed a cobbled gutter, came to a halt in the middle of the next block and looked up along a drab tenement facade. Most of the windows that broke the dingy brick wall were blind but on the second floor light lay yellow against the oblong of a pulled down shade.

Doc nodded, went into a black vestibule crowded between two store fronts. There was no need for him to find or ring a bell, the people who live on Morris Street have no possessions valuable enough to be guarded by locked street doors. A grape-size electric bulb made the obscurity within a narrow hallway a little less than complete darkness. Narrower, uncarpeted stairs creaked even under his light tread as he climbed.

Someone on the second landing had had boiled cabbage for supper, its pungent aroma overrode the other smells, of exotic foods and mouldering plaster, and other less pleasant smells that combined to form the musty odor of poverty. Another tiny bulb laid its wan luminance on pencil-scribbled walls, on paint-peeled doors. Turner moved to one of these, rapped lightly.

There was, within, an impression rather than the sound of someone moving about, but no one came to the door.

Doc knocked again.

A PASSING "El" train made distant thunder. The tenement's

ancient fabric trembled to it. The noise died away and the door

still had not moved, and behind it there was silence. "Marta

Sigurd," Doc called, just loud enough for her to hear if she

stood frozen in fear on the other side of the door. "Marta. You

can open for me. I'm your friend, Andrew Turner."

His hand, instinctively on the knob, turned it. The door was unlatched. It was opening, on the room that is foyer and kitchen and living room in a tenement flat. This room was unlighted but in the wall opposite were two doors. One, to the room Turner knew had been Bronko Maslyk's for twenty years, was tight shut, its lock white-splotched with a police seal. The other hung half open, and the aperture was filled with yellow radiance.

It was wide enough for Doc Turner to see through. What he saw clamped invisible fingers on his throat and held him momentarily incapable of movement.

He saw the foot of an old-fashioned iron bed. Her back to it, was a wisp of a little woman with sparse gray hair and face wrinkled like the skin of a dried apple. The seamed face was dark with agony, and blood dripping over its bony chin streaked with scarlet a faded housedress that had been clean and crisp when it was donned.

The blood crawled slowly from thin, old lips savagely torn by a black cord that came to them from over Marta Sigurd's left shoulder and was caught between them and went tautly down again over her right shoulder to a link of black that lashed her arms behind her back, cruelly tight just above the elbows. Another cord was knotted to one end bedpost and went through behind the woman's arms to the other, but this sagged loosely. It was the harness that held her in a rigid, unnatural posture or, when fatigue compelled her to slump, slashed excruciatingly into her lips and toothless gums.

It was an ingenious torture device. It forced the victim to torture herself.

Doc pulled in a quivering sob of breath and got back the use of his limbs. He went swiftly through the immaculate kitchen. The window-shade bellied inward as he opened the door and went into the bedroom. Then he was slashing, with a penknife at that Satanic harness.

In Marta's throat there were tiny, pitiful whimpers. In her bulging, bloodshot eyes came incomprehension at first, then a flame of thankfulness. The cord was tough, rubbery. It resisted the blade, turned the knife in the druggist's trembling hand. Doc took hold of the cord to try and ease Marta's mouth, jerked impatiently upward.

The cord snapped.

Marta Sigurd sighed, sagged forward against him. She'd fainted, mercifully, but she was still held to the bed by the line between the posts. Turner contrived to sever this as he held her. He lifted her in his arms and she was almost weightless as he laid her upon the bed.

As he cut the cords lashing her elbows he glanced around the bare, Spartan room. There was no evidence of a struggle. The door of a closet was open but the clothing within, the few dresses of a very old woman, hung neatly and newspaper-wrapped bundles on the shelf above obviously had not been moved for years. By the window was the chair in which Marta Sigurd would sit watching the teeming life of Morris Street and on its sill, half-hidden by the drawn down blind, was the cushion that softened the wood for her when she leaned out.

Doc's look came back to Marta. She was very tiny on the thick, soft-quilted bed. His fingertips found a pipestem wrist and the pulse was a faint flutter.

The druggist dropped the wrist and pushed himself away from the bed, went out to the kitchen. He turned on a sink tap—there was only one, tenement dwellers heat their own hot water—plucked a clean dish towel from the rack above it. Soaking this, he hurried back to the bedroom.

He was well into it before he saw the grotesque, incredible shape that bent over the bed. It whirled to him. Doc saw a hairy mask, eyes like two pits of hell.

The Thing leaped for him. He flung the sopping towel at it and then a stunning blow split his skull, let sick blackness into it.

JACK RANSOM pulled on his dungarees, zipped them. A chain

hoist had already lifted the giant truck motor off its chassis

and a couple of helpers were clamping it into the welding jig.

Danny had laid out Jack's tool kit and was standing by with his

asbestos hood.

"Where's my double-X gooseneck," Jack asked him, "with the twist head?"

"I—uh—" The light was suddenly out of the boy's eyes and they were miserable. "Gees, Jack. I was cleanin' it up an' the head was stuck an' I put it in a vise to get it loose an'—"

"Smashed it." Two white spots showed at the wings of Ransom's nose. "That's the only pipe I can get at the far end of that crack with—and it was the only one in the shop."

The boy's mouth opened and he looked like he was about to cry. "Gee. I—"

Jack squeezed his shoulder, said, "It's all right, kid. Bob Merrill at Acme has one and he's on the MacArthur shift there."

"Gee, I'll go and—"

"With me, kid. Bob's one of those crabby old-timers if you ask to borrow a tool from them it's like asking them to cut off their right arm and give it to you. I can wangle it out of him, but I'm the only one who can. Look, you gas up my jalopy and wheel it out. I'll tell these guys just how I want this crack filed."

Danny scuttered off, smiling again, and Ransom gave his helpers very explicit instructions. Then he was in his battered roadster, with the kid beside him and he was wheeling into Morris Street.

The little car rattled as if it were about to fall apart, but the motor under its tinny hood sang sweet and powerful. Jack slowed it, going into the second block and glanced up at a tenement's dark facade.

His heel pounded the brake pedal. "Stay here!" he snapped to Danny and had vaulted the car's door, was across the sidewalk before it skidded to a stop.

In the window for which he'd looked, recalling Doc's mission, he'd seen a gargoylesque face, an arm curled about a dangling, limp body whose hair had gleamed silvery in radiance from behind.

He took the stairs three at a time, catapulted through an open hall door, to the yellow slit that marked another, not quite closed. He jerked this open, slammed through, dug heels to stop himself, gaping.

On an old-fashioned iron bed lay a twisted, bloody form, its head askew in a way that told indubitably the neck was broken. That was—had been—Marta Sigurd.

There was no one else in the room.

"Doc," Jack groaned. "Doc!" No one had passed him on the stairs and no one had been on the landing above as he hurtled to it. He'd reached here so quickly that no one could possibly have gotten across this room and across the kitchen and out into the hall without being seen.

THE window! Jack got to it, leaned out. Danny was in the

roadster below, leaning back at ease. If he'd seen someone drop

from here—

A sense of movement jerked Jack's head up. Straight ahead of him, not five feet away, he saw a black huddle drop off the "El" railing to its inner side.

He was up on the sill, crouching. The dark mass over there straightened up on the track-walkers' two-foot board walk, started to move off. It was a dark ungainly form, stooped, shambling. Doc lay across a huge shoulder, dangling.

Twenty feet below, the concrete glimmered palely in the dimout and across the gap was only a toothed row of wide-spaced tie ends. Jack's thighs straightened, hurled him over the menacing abyss.

His left foot found only vacancy but his right caught the edge of a tie—slipped off! Frantic hands caught horizontal pipe, the rail, and the weight of his body jerked at his arms. His kicking feet thudded against wood. The brute on the catwalk heard, whirled. Light from Marta Sigurd's window shone on its face and it was the furred mask of a beast. Red sparks of a beast's eyes glowed through the shaggy mass.

It dropped the flaccid old man, lurched toward Jack.

Jack got shoe soles to the ties just before a black claw flailed for his eyes. He dodged the curved talons, threw a sledgehammer blow into the creature's chest. The black shape staggered back and Jack vaulted over the rail.

The fur-faced thing returned to the attack. Ransom met it with hammering blows—but spring-steel arms wound round him, hugged him to a foul-smelling body.

His fists pistoned into what felt like a steel washboard, fabric-covered, and yielded to the jolting blows as little as steel would have. Jack felt himself borne back against the rail, braced himself to resist the inexorable strength that meant to toss him over it.

The cords in his thighs tautened, seemed about to cut through their sheath of skin. He was gasping for breath, knew he could not stand much more of this.

He saw Doc's still form, across a gleaming track and he saw, blocks away but coming fast, the black juggernaut of a train roaring toward them on that same track!

The sight exploded in him a strength he did not have. His piledriver fists broke his opponent loose, staggered him back, but the uncouth black shape was between him and Doc.

The furry creature leaped in to crush him. Jack dropped to his knees, clamped arms about scissoring huge legs, heaved upward. The creature's momentum carried it up and over Jack's head—but suddenly it jarred to a stop.

Hands had clutched the railing, held. The train's noise was deafening, earth shaking. Ransom called on his ultimate ounce of energy, lurched up—heard a shrill scream as the dark shape whirled down to waiting concrete.

Jack leaped into the terrible thunder of the train, scooped a frail form from shuddering tracks, flung sidewise. Vertical pipe caught, stopped his roll and the thunder was beside him now, possessing him, and then it was rolling away and he was still alive and the body his arms embraced, held to him, was whole, unharmed.

A wave of giddiness darkened thought. He felt a stir against him, heard a voice. "Jack. Jack, boy." Doc Turner's voice. "How—how did you get here?"

The youth told him, disentangling himself, pulling himself painfully erect. "The stink of that guy's still in my nose," he said bleakly, "and I can still see his face." He shuddered. "It was more like a dog's than a man's. It was all fur..."

Afterwards he was to recall the queer thing Doc said—"A furred face, eh? That fits in—" but just now he gaped over the "El" railing to the street below and an icy prickle scampered his spine.

He'd thrown his antagonist over this rail, twenty feet to concrete. No human could come through a fall like that uninjured, but down there the sidewalk, the gutter, showed no sprawled shape, no black and shattered form trying to crawl away.

Except for his roadster, skewed to the curb, Morris Street was utterly empty.

But Danny must have seen what happened. "Danny!" Jack called. "Dan."

The boy didn't move, didn't look up.

"Danny!"

Jack's mouth went dry.

There was something queer about the youngster, something unnatural. His head lolled back on the seat-top.

Jack Ransom groaned. "He—

"Come on. Doc. We've got to get down there quick."

HE had to run to the station, two long blocks away, had

to run back again down two long, echoing blocks of desolate

sidewalk. He was breathless when he reached the roadster and iron

bands constricted his laboring lungs. But he managed to clear his

vision and look with dilated pupils at the still, small form in

its seat.

He saw a bloodless slit running around the grease-smeared, thin neck. He saw a twist of cord curling out of it, a black spiral like the tail of a mouse.

A hand laid itself on Jack's shoulder. He turned, stared blindly into Doc Turner's bleak face. "I thought I was being good to him," Jack moaned. "He was all broken up over smashing my gooseneck and I thought I'd make him feel better by taking him along with me. I—It's my fault he's dead."

"No," Doc said. "No, Jack. No more than it's mine that Marta Sigurd is, even though if I hadn't gone to get some water to revive her—

"It isn't our fault that Danny or Marta or Bronko Maslyk have been murdered, but unless we do something about it, there will be more deaths on Morris Street."

"What can we do, Doc? How do we start?"

"By getting away from here before Tim Flannery comes along pounding his beat, and brings Captain Jameson and the Homicide Squad to hold us here for hours while a killer runs loose. Come along."

"And leave Danny?"

"Come along, Jack. I need you."

"Okay, Doc."

"Good. I'll tell you my plan as we go along..."

THREE-QUARTERS of an hour later, Doc Turner was alone as he

once more climbed creaking tenement stairs. Two flights again,

but this was in the third block down Morris Street from Hogbund

Lane.

The rap of Doc's knuckles made an odd pattern on a door. He repeated it, waited. After a while the knob rattled, but the door did not open. "Who?" a heavy voice demanded through the panel.

"Doc Turner, Hendrik. Let me in."

The door opened, admitted him to a pitch dark room. It closed again. He heard a key click, then light came on. "Doc Turner, my friend." The man was very tall and once he had been very fat but now his nightshirt hung loosely upon him and his cheeks were pendulous, flabby folds. "How did you know our signal?"

The pharmacist tugged at his bushy, white mustache. "It wasn't hard to guess." He carried his head with an odd stiffness. "One long rap and three short ones. What other signal would you use?"

Hendrik van Goort rubbed a palm over a pate that had only a mossy fuzz of gray hair. "Vot other signal, indeed?" His eyes, deep-sunken, were like burned-out coals. "Ve shall haf to change it." He spoke precise English but now and again the Hollander accent broke through. "Ve—

"Holt on! Vot makes you think I haf a signal with anybody?"

"You forget, my friend, that I have an insatiable curiosity about everything that happens on Morris Street." Doc smiled wanly. "When you suddenly begin calling on an old Norwegian woman whose existence you were never before aware of, and when a middle-aged Pole like Stanislaw Pasgiudski starts dropping into your barroom every evening, there must be a reason. And when a similar odd friendship crops up between Pasgiudski and an aged Frenchman like Rene Laconte, and between Laconte and a young widow from Belgium, Marie Dupuys, then something is going on. And about what it is—becomes reasonably plain."

Van Goort took hold of the top of a chair, his fingers flattening. "Yes." His dewlap quivered. "We were not so discreet as we thought."

"You are all from countries that have fallen prey to the Axis. Like Bronko Maslyk. You know that Bronko was murdered today, don't you?"

"Yes, I have heard."

"You cannot have heard that Marta Sigurd is dead also. Horribly. You must be frank with me, Hendrik, or the rest of you will die too."

Tiny light worms crawled in the Hollander's little eyes. "Vot is it you want to know?"

"First, exactly what are you doing?"

"Listen, then. We are too old to bear arms, or we are women, but hate for the German and his dupes burns in us as strongly as those who can shoot him, and drop bombs on him and twist cold steel in his body. We have found our own way to fight him. We all know how, for long years, they nibbled like rats at the foundation of our homelands, how they have eaten like vermin their walls till they were rotten and ready to fall. We know that the rats are here, and the vermin, and we know their foul ways.

"Marta Sigurd, watching from her window all day and most of the night, saw things no one else might. In my saloon tongues sometimes wag a trifle too freely and in the beauty parlor, on Garden Avenue, the prattle of women on a hair dryer often reveals matters they do not know they know. Rene Laconte runs an elevator in the Savoy-Ritz and conversations sometimes last for a phrase or two after an elevator door opens. So with the rest of us. We keep our eyes and our ears open and we put together the meaningless little bits we see and hear—and now and then, put together, they take on meaning. Then one of us makes an anonymous call to your F.B.I. and—

"Well," a note of triumph came into his voice, "you read of arrests, and there are arrests of which you do not read."

Doc watched his own thumb rub the top of the round table by which he stood. "The wrath of the Terrible Meek," he murmured. The roar of a passing "El" train beat against him, and a bedroom door that led from this room rattled in its frame. He looked at van Goort and said, "The second thing I want to know from you is the name of the latest recruit to your circle."

The Hollander's lids hooded his eyes. "Recruit?" he murmured.

"A Filipino, isn't he?"

"No, a Javanese. He came to me with letters that showed he'd been head of household to my brother, Koort, in Batavia." Van Goort checked. There was belated surprise in his voice as he asked, "How did you guess?"

"I didn't guess," Doc said, stressing the last word. "Tell me his name and where he can be found, Hendrik, unless you want yourself and the others to die."

A shudder ran through the emaciated frame that once had been rotund. "I understand, now. One of the rats has crept among us. He is known to us as Pandru Ktut and he lives—" Van Goort broke off, his brow furrowing. His bitter lips moved in a an apologetic smile. "You will have to forgive me. I've forgotten. I have his address written down. Vun moment and I will get it for you."

He padded across the kitchen linoleum to the door beyond the stove, opened it on darkness and shut it again behind him. Doc stood very still, waiting for him to return, a nerve ticking in his grizzled cheek. The bedroom door opened again. Van Goort left it open as he came heavily to Doc. "Here it is," he said, and thrust a slip torn from the edge of a newspaper at the old man.

The druggist took the slip, read, "847 Morris Street, third floor, rear. Thank you, Hendrik. I shall pay a little visit to this address before morning, but not alone." Then he asked, "Have you had any word at all from your daughter since that one message you told me of, last year?"

"Greta." Agony twisted the Hollander's face. "No. Not the least hint that she is—" His voice broke.

Doc finished for him, "Alive."

"Alive?" A croaking laugh spewed from pallid lips and for an instant van Goort's eyes were windows to a damned soul. "If only I were sure she is dead, I could sleep nights."

"Yes," Andrew Turner murmured. "Yes, I imagine so." He hesitated, pity in his eyes. "Well... Thank you, Hendrik."

HE plodded along Morris Street, a feeble little man

stopped under the weight of his years. In the middle of the block

ahead, four cars were skewed to the curb and even in the dimness

he could make out that three were colored the green and white of

the police. About the fourth, and about the street door of Marta

Sigurd's tenement, was clustered a knot of the strange people who

spring out of the very sidewalks whenever something happens in a

city. A nighthawk taxi shot by, went past the sidestreet ahead,

slowed as its driver spied the little crowd. Something flicked

down past Doc's eyes, closed on his neck!

It jerked him to a stop and he pawed at it, at the cord tightening on his throat. He got nails under it, could not get it free. In terrible silence he fought it, folded down to his knees. His hand, fumbling beneath his ear, found a stiffish twist of cord, like a mouse's tail...

Someone in the crowd shouted suddenly, pointed, and Tim Flannery broke loose from the dark knot, pounded with desperate speed along the sidewalk. He reached the kneeling form, plowed to a stop, went greenish as he spied the lethal twist of cord. "Another one," he grunted. Then, "Gawd! It's Doc!"

"Watch it!" A sudden shout from above, "Watch below!" sent Tim jumping back from under a black sprawl that swooped down, squashed sickeningly on the pavement. It squirmed and flopped over and he saw a round, Oriental visage, high-cheekboned, brownish rather than saffron. The beady black eyes cursed him and glazed and a bubble of blood burst from the straight gash of mouth.

A wild laugh rang out from the "El" trestle. Flannery's gun leaped into his hand, jabbed upward at the pale blob blossoming over the rail. "Don't Tim," Doc Turner commanded sharply. "Don't shoot. That's Jack Ransom."

Doc was coming spryly to his feet. Tim squealed, goggling at him, and the old druggist grinned. "No, son. I'm not a zombie. This noose didn't strangle me because I've a plaster of Paris cast around my neck, painted with flesh color collodion—liquid court plaster to you."

The crowd from the next block were jostling about them now, but the old druggist seemed unaware of them. He looked down at the dead Oriental, his smile vanishing.

"There's the rest of the deadly thing." From one clawed hand there snaked a long length of the lethal black filament. "He lassoed me the same way he did Bronko Maslyk, from the "El" catwalk where no one would think to look. He'd nicked the cord so that when he jerked it, it would snap an inch from the knot. When that happened as I was trying to get Marta Sigurd loose, I realized why Bronko folded down the way he did. The cord held just long enough to keep him from sprawling. It made him seem to be sitting like a dog."

Captain Jameson pushed through the crowd. "There's your killer, captain," Doc told him. "Of Maslyk and Danny Jones. The poor boy got it because he'd seen things he must not live to tell about, and the dog-faced man had to be spirited away since if he'd been found someone might have identified him as a hairy Ainu—"

"A what?" asked the captain, cocking his head at Doc Turner.

"An Ainu," the old pharmacist repeated. "An aborigine from one of the northern Japanese Islands, Kunashiri or Aino itself. That would have been a dead give-away, but even before I saw him I knew the killer was a yellow rat. If you'd read Marsman's account, you would have known it too. He tells how they used that sweet little torture harness on the British soldiers they captured in Hong Kong."

"OKAY," Jack Ransom muttered, the next afternoon. "Okay.

I see now why you had me hide up there on the "El" trestle and

trail you when you came out of Van Goort's house." His face was

lined, drawn, and there were dark pouches under his bloodshot

eyes. "And since you'd pretty well guessed what Maslyk and Sigurd

and the rest were up to, I can see how you figured some Axis

agent had joined up with them to ferret out the whole gang and

stop them."

"The only way they could."

"Yeah. But what I don't get is why you were so sure if you went to van Groot, he'd set the murdering rat after you."

"The fact that he had a daughter in occupied Holland. A father might be willing to have his son killed as a hostage, but when it comes to what they can and would do to his daughter—"

"Yeah." Jack looked sick. "Yeah. That's why you didn't turn Hendrik van Goort in to the F.B.I."

"That's why, son." Doc rubbed his spatulate thumb along the edge of the showcase by which they stood. "Perhaps I am wrong, but I've told the Frenchman, Laconte, and he'll pass the word along to the others, so he'll be harmless now."

He moved a bottle of cough mixture from one spot to another on the scratched glass case-top. "But let's not think about that. Why don't you go home to bed, Jack? You look like you haven't slept for a week."

Ransom yawned. "Not for forty-eight hours, anyway. I had to finish welding that cylinder block, didn't I, and get that damned truck rolling?"

"You've done pretty well for a youngster the marines won't take because of a bad heart."

Jack grinned happily, "Well, I finally got to slap one Jap down, anyway!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.