RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

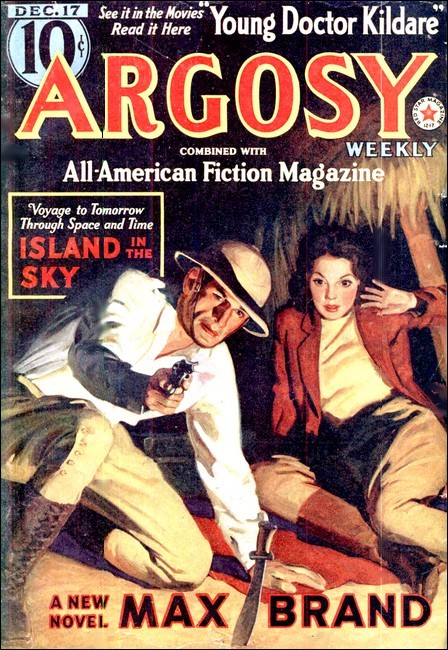

Argosy, 17 December 1938, with "Island in the Sky"

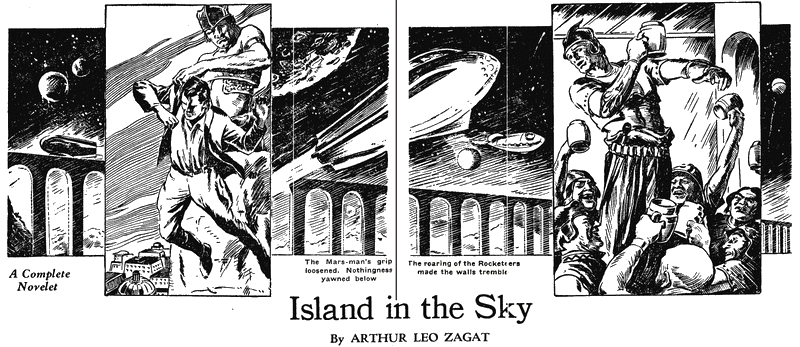

Headpiece from Argosy

Into the darkness of Outer Space they flew, seeking in the

future the secret hoard that the past knew so well how to guard.

NICK'S was a bedlam that night, a riotous madhouse. They were lined three deep at the bar; and the tables were jammed; and not a woman among them, for no woman dares enter where the Spacemen are gathered for a Zanting.

For hours I had had literally to fight my way through the crowded aisles and I was soaked, half-blinded, with sweat. My head swam with the fumes of the dregs in the empty glasses I carried, the potent fumes of the greenwine Nick Raster smuggles from Jupiter. Every muscle in my body housed a separate ache—and my pulses pounded with elation that I was a helper in the Tavern of The Seven Pleiades.

Where else could a lad of eighteen mingle with those who roam the trackless reaches of Interspace? Where else could he serve the men whose breasts bear the proud sunburst, gold for the controlmen, silver for the master rocketeers? Where else could he hear such brave talk of ether-swirls and meteor-storms, of the drowned, incredible jungles of Venus, the sandbeasts that haunt the waterless plains of Mars, all the marvels of the planets beyond the sky?

Kitchen drudge? I was a seraph among demigods!

A burly form in the black uniform of the I.B.C. shoved back to give me room. In the partition at the rear of the room a door swung open for me, closed behind. Web-fingered, nailless hands relieved me of my tray.

I leaned on the aludur sink-edge for a moment of rest, sluicing sweat from my brow with the edge of my hand. I wondered if ever I would wear the rocketeer's black uniform.

These were fool's dreams. Rocket-cadets are chosen only from the highest-ranking graduates of the universities, and I had only an orphan's scant schooling. The most I could hope for was a mechanic's berth in the shops of Newyork Spaceport, out there beyond the walls of the tavern, grooming the great flyers when they homed, pitted and scarred, from their journeyings among the stars.

If only I had been eighteen twenty years sooner—before the Triplanetary Union was formed and the Interplanetary Board of Control given absolute power over all between stratosphere and stratosphere. A man could fight his way up from fuel-hole to control-cabin then. I might have....

A sudden silence, beyond the door through which I had come, cut into my thoughts and turned me to it. Before I could get into the photo-cell beam that would open that door, the first foot-stamp shook the tavern, the stamp of a hundred feet setting the cadence for the Song of the Spacemen. The second thundered as I came again into the room beyond and saw them all standing, the pilots of the void, their eyes aflame, their glasses raised above their jaunty heads. The third crashed as I froze stark-still in the doorway, and on the fourth down-thump of heels the heart-stopping chorus roared forth:

Blast old Earth from under keel!

Set your course by the stars.

Spurn apace Sol's burning face.

Give our greeting to Mars....

THERE he was, slender and lithe, high on a table above the

shouting throng, the man to whom they sang, Master Darl Barton of

the Rigel, his silver sunburst ringed by four stars, one

for each year he had conned the spaceways. His head was thrown

back, and lifted to his lips was the mug of greenwine that he

must drain, as was their superstition, before the song ended, or

die on the journey he started at dawn.

He had called for that test of disaster or safe return, or they would not be singing it. Not many were brave enough to cast that gage to fortune.

Crash! The feet thundered in the breathing space of the song.

Comets set your cosmic pace.

Wide and free you soar.

Say goodbye to the earthbound race.

Back you may come nevermore....

Back to Earth nev—

THE song broke into ear-splitting cheers as Master Barton

upended the mug to show that not a drop remained within it and

then flung it down hard on the table at his feet, smashing it

into a hundred shards.

His weather-lined face was scarlet from gulping the wine down without a breath. His eyes narrowed. He was pointing, none too steadily; his mouth moved so that I knew he was shouting something, though what it was he shouted I could not hear because of the din.

And then, abruptly, everything was still, and there was only Darl Barton's thick accents. "I mean you. You di'n't stan' up for me. You di'n't sing for me."

Yes, everything was still and quivering as the taut instant before blast-off. Because for a rocketeer to refuse to stand and sing the Song of the Spacemen when it has been called for is the ultimate insult to him who has called for it, and there is only one way the insult can be wiped out.

Faces were turning to see who it was Barton challenged, faces grave suddenly, and unsmiling. I turned too, to the table beside where I stood. There was a narrow space cleared about it, and there was only one man seated there.

I saw only his hands at first, bigger than common, their joints knobbed, blue veins ridging the gray, almost transparent skin. They were pressed down flat in the slop that wet the table-top, and the black cuff of one uniform sleeve was wet with greenwine that spilled from a glass just then overturned.

"You didn't sing for me," I heard Darl Barton repeat, and I heard a thud that I knew must mean he had jumped down from his perch.

The crowd was shoving aside to make a path for him.

The face of the man at the table was gaunt and hollow-checked. It was etched deeply by the network of fine wrinkles with which space marks its sons, and the eyes were eagle-hooded. In those eyes I read neither fear nor defiance; only agony such as I had never before seen. The thin lips were pressed tight and blood-drained by the same bitter pain.

Master Darl Barton reached the table and halted before it, his left hand clenched until it was white at the knuckles; his right half-curled and hovering above the butt of the heat-gun holstered at his belt.

"Get up," Barton said, his voice thick no longer with drink, but with his wrath. "Get up," Barton said again, and his hand closed on his gun.

He would say it once more, for the third and last time, and then, if the other did not rise to apologize or defend himself, it would be Barton's right to burn him where he sat. So the Code says, and even the I.B.C. dares not interfere with the code of the rocketeers.

Someone was counting aloud the ten seconds that must intervene between the second demand and the third. "Three!" the voice said. "Four," and the man at the table did not move. "Five," the voice said. "Six." A throb in my temple kept time to the slow thump of the numbers. "Seven." I was going to see a man die. "Eight." On the night of my first Zanting, I was going to see a man die. "Nine."

"Ten."

"Get up!" Master Darl Barton said, his gun sliding out of its sheath. The man did not lift. But he gestured with his hand.

"You fool!" he said. "Are you blind?"

Barton's gun dropped from his fingers, unfired. "Gemini!" he groaned. "It would have been murder."

IT would have been murder. For the breast of the man's

black uniform coat bore no sunburst. He had not insulted Master

Darl Barton by refusing to sing the song of the Rocketeers. He

had not the right to stand and sing it. Not any more.

At the last possible instant his hand had lifted and pointed to the place on his breast where the fading of the cloth around it left darker the outline of the sunburst that once had been sewn there.

The outline of the sunburst, and of the stars that had ringed it....

I knew now the reason for the agony that lay in his eyes and made his thin mouth bitter. I knew what it had cost him to sit there and listen to the song, what it had cost to point to the place on his breast where the sunburst once had shone.

I knew, and all knew that were near enough to count the marks of the stars he'd once worn, who he was. Eleven stars we counted. Eleven.

In all the history of the craft, one master rocketeer—one only—has had the steel to endure more than a decade of conning the spaceways. This was that one. This was Rade Hallam.

For another minute Darl Barton stood staring. Then from his lips spilled laughter so laden with scorn and contempt that it was like a slap across the face of the man before him. He spun on his heel, and cried in that great, young voice of his. "Greenwine, Nick! A mug of greenwine to wash the stink from my throat."

"Greenwine!" or "Lanrid!" or "Whiskey!" the others cried, and the waiters were fighting again through the swirling mob, their trays miraculously balanced above the brawl.

Every black-clad back in the room was turned on the man at the table and, crowded as the room was, there was a space about that table as though the man who sat there were marked with the yellow boils of the moonpest.

Straight and proud he sat, but the black flame in his eyes was dying. I saw his hand fumble for the glass that had overturned, and I saw the empty glass lift to his colorless, tormented lips....

"May I get the master something?" I asked, wiping the table with a dripping towel.

"Slota," Rade Hallam mumbled, staring at the wall of backs that shut him out of the Zanting. "A double slota."

Now slota, brewed from the scarlet popquin whose fields give Mars its red hue, is liquid fire in the veins and a trinite bomb in the brain of an Earthman. For an Earthman to drink it is to court madness or death.

"Perhaps the captain would prefer some more of the greenwine he has been drinking," I ventured.

"I'll have slota," he growled, his dreadful eyes lifting to my face. "And I'll remember you're my controlman and not my nurse, Toom Gillis."

I WENT cold with the sound of my name on Master Rade Hallam's

lips; and then his own face was ashen and he was slashing the

back of his hand across his eyes as though to wipe some mist from

them. He was half-risen to his feet, and his pupils were

dilating, and words spewed from his twisting mouth.

"Toom's voice! And Toom's face! But I saw you dead, Toom Gillis! I saw your corpse spill out of the gap in the Terra's pithed skin! You're not Toom Gillis! You can't be."

"I am Toom Gillis," I squeezed out. "But I am not the Toom Gillis you saw die, six years ago. I am his son."

"His son," Hallam breathed, crumpling into his chair, an old and emptied man. "You are Toom Gillis' son and you do not curse me. Do you not know who I am?"

"I know who you are, sir," I replied. "And I know no reason why I should curse you."

"I lost my ship and killed my crew, your father among them. I fled the wreck in the one man-shell that had not been smashed, so because I lived some one other of my crew died, and that other might well have been your father. Reason enough, it seems to me, for you to hate me."

"Reason enough if it were true," I responded. "But it is not."

"The Council of the I.B.C. said that it was, and stripped me of the sunburst. And the Craft believe it is true, and turn their backs upon me. But you—"

"But I know that if the Terra was pithed, no man could have saved her. I know that if you left her, living, you left no living man behind you. I know that if you did not die with your ship and your crew, there was some sufficient reason why you must outlive them."

Rade Hallam's head lifted and his eyes found my face once more, seized my eyes. "You know," he whispered. "You say you know—but how can you? I did not tell my story because I had no witness—"

"I had a witness," I answered him. "My father. The Rade Hallam my father served—and loved—could not be a coward. He could not betray—" Bruising fingers dug into my shoulder, twisted me around.

"Did I hire you to loaf?" Nick Raster roared down at me from his immense height. "And monkey-chatter while we gasp for glasses behind the bar?" His one lash-less eye glared out of the scar that made a horror of his face, and the stump of his left arm jerked as though it were jolting into me the fist that a fuel-tank explosion had ripped from it. He flicked me from him and I crashed into the wall.

"And you!" Raster swung to Rade Hallam. "I'll have no such scum as you in my place. Out! Out, or I'll whistle up the dogs to chew you out."

Hallam's hands shoved down on the table-top, lifting him, and when he was on his feet his graying hair was scarcely level with Nick's chin, and his body was half Nick's width. For a long moment he said nothing, and did not move, but Raster gave back from him, step by slow step, his gross lips blanching.

And then Hallam spoke, his tone so low that only Raster and I could hear him. "Whistle up your dogs, Nick Raster. You would be very wise to whistle them up and have them make an end of me."

Raster's hand crept to the whistle that hung by a chain from his bull's-neck and the fingers of fear took me by the throat. The dogs that whistle would summon were no Earth beasts, but hounds trained to hunt the mammoth stoora in the Venutian marshes. They could rend a man in a split second.

Raster's hand closed on the whistle. And opened again. It seemed to me that in the breath before his hand dropped away a gleam of evil shrewdness had come into his single eye and at once been veiled.

"Go." he muttered. "I want no more trouble here."

Hallam's lip curled in scorn and he turned his back on Raster, and Raster turned to me as though glad of an excuse to turn somewhere. "You still here!" he bellowed, and started for me—my soggy towel splashed full in his face.

"Leave me alone," I sobbed, ripping my apron from my waist. "I work no place where he is not welcome." The apron followed the towel, hiding Nick's ugly head.

It was my luck that thus blinded by rag and apron the innkeeper could not see to grab me as I dove into the swirl that had made way for Rade Hallam and had not quite closed again behind him. Raster's roar followed me but I caught up with Hallam at the tavern door and got safely out into the midnight chill.

LIGHT spilled out after me, across the wide viaduct, to lay our shadows on the towering boundary-fence of the Spaceport. Then it was dark to my burning eyes, but not too dark to discern Rade Hallam's gaunt frame, nor for me to see him halt and sway. My arm was around his waist before I quite knew I had sprung to his aid.

"Easy, sir," I murmured. "Easy. The fresh air often hits hard, though till you get out into it the greenwine seems not to have touched you at all. Easy, Master Hallam."

"Toom," he muttered drowsily. "Good ol' Toom."

"On deck, sir!" I snapped it out crisply, as Dad had taught me, he my master and I his controlman in my room at Mother Gore's that we pretended was a spaceship's cabin. Perhaps the familiar ritual would bring Hallam out of his befuddlement. "What's the course, sir?"

I felt him stiffen against me. "By Antares, mister! If you try once more to get the course of this voyage from me, I'll disrate you." Again mistaking my voice for my father's, he was reenacting some scene that had occurred six years ago. "The controls are sealed and—" He broke off. "Toom!" he exclaimed. "Look at those seals. Someone has been tampering with them."

"Tampering, sir?" A chill stirred my skin with the weird sensation that I was repeating words said long ago and far away. "No one could get in here without you or me knowing it."

"No one ... of course not," The fumes were fuzzing his utterance once more. "I musht be mishtak..." My arm took his weight, and his head lolled over on my shoulder.

Now what was I going to do? I had no idea where he lived, and I had no place of my own to take him. It would be sheer suicide for me to return to Nick's tavern.

The muffled tumult from within the tavern served only to emphasize the desolate loneliness about me. Even the overcast sky was empty of all but the few trailing lights of the late home-farers on the local plane-level.

The soaring dark towers of the city, the leaping arabesques of its foot-bridges, light-spangled against the sky-glow, seemed infinitely distant. Here, within a mile of Newyork's teeming fifteen millions, I was utterly alone with this helpless burden.

Or was I? Abruptly I had the hair-bristling sensation of eyes upon me, somewhere in the dark.

The blank, windowless front of Raster's place loomed over me ominously enough, but it gave no hint of any watcher. The black shadows lay against the black spaceport fence, and nothing stirred within them.

I must be wrong, I assured myself, yet I knew that I must get away—somewhere, anywhere. I bent, slid my free arm behind Hallam's knees, lifted him.

He lay limp across my arms as I hurried away.

AHEAD, a white luminance spread about an exit gap in the

viaduct wall where a descending ramp began. Somewhere below, in

the huddle of ancient structures along the base of the spaceport

fence, I would find us shelter.

I veered toward the opening in the viaduct wall; halted as a huge shadow detached itself from one side-post of the aperture.

It was a Martian who lumbered toward me, his monstrous frame clad in the metal-fibred working suit his race affects; his lidless eyes peering inquiringly at me and my burden. The great size, the green-hued visages, of the people of the red planet make them rather appalling, but they are really mild-mannered and gentle and harmless. I started moving again—

Then without any warning of word or gesture, the giant leaped. I could not dodge him before he had snatched Hallam from my arms and pounded me down with a tremendous blow on my chest.

I rolled, thrust hands against the viaduct-deck, shoved myself up to hands and knees, gained my feet. The Martian was just vanishing into the gap out of which he'd come. I threw myself after him, bounding high to hurl a fist at the point where the spine enters the brain-case, the blow that struck just right will stun a Martian.

I missed! The fellow spun—Both his hands were free—and reaching for me.

I got in one blow at his belly; another; and I might as well have been pounding the viaduct-wall beside him for all the effect it had. His fingers caught up the collar of my jacket and tightened. He lifted and swung me effortlessly over the top of the wall. He held me there, gasping and squirming.

I dangled limp over a black and terrible void. Three hundred feet to the hard roadway below.

"No!" A girl's voice called out, imperious and steady. "Put him down, Atna. Put him down this instant."

The Martian's blue lips twisted, and his head turned. "Why no?" I heard him rumble. "He hurt bahss. Why I no drop him?"

"You mustn't drop him because that would kill him," the girl's voice was explaining, patiently. "And it is wrong to kill anyone, even an enemy." The wall hid her from me.

"I no kill my enemy," Atna insisted stubbornly. "But I kill bahss's."

I licked my lips and squeezed out speech from the tightness of my throat. "I'm not your master's enemy. I'm his friend. He is sick, and I was trying to help him. Ask him if that isn't so."

"He sleep. I no can ask him." Atna's brow wrinkled at me. "You say you bahss's friend?"

"I swear it."

He grunted deep in the cave of his chest and lifted me back over the wall, set my feet on the ground once more. If he hadn't held me up, I'd have crumpled. My legs were jelly.

I gulped. "Thank you, miss." My vision cleared and I saw the girl who had saved me.

She was slim as a willow-wand swaying in the wind, very boyish in her knee-length skirt. But her high laced-boots outlined finely curved legs and the soft cloud of her brown hair framed a pert-nosed, impudent little face.

I contrived a sickly smile. "Thanks," I said again. And, "Thanks," once more.

Such poor eloquence as I possessed had been scared out of me.

Her moist mouth did not smile; her gray eyes were wary. "What—what have you been doing to Uncle Rade?"

"Nothing that deserved being smashed to pulp for. He's sick and I—"

"He's drugged, that's what he is. Where—"

"Neither sick nor drugged, my dear Mona, but drunk." Rade Hallan's foggy voice came out of the shadows. "Three glasses of greenwine put me under; me who once could down thirty without blinking. I got into trouble—and this insane infant did what he could to help me. Then, ungratefully, I passed out."

"It's lucky," the girl said primly, "that we came looking for you. You were gone so long." Abruptly her eyes moistened with tears; and I knew that she was very young, sixteen or seventeen at the most. "I was so frightened—"

"You need not have been, Mona." Hallam drew her to him. "I had Toom to take care of me." He laid his hand on my shoulder, and I was proud.

"Toom?"

"Yes, Mona. This is Toom Gillis, the son of—Cygnus! Why is Atna clutching him like that?"

"We thought that he—"

"They thought I had done you some harm, sir," I broke in. "And I have had a little difficulty convincing them otherwise. I—"

"Release him," Hallam snapped. The big fellow let go of me. Whereupon I slid incontinently down in a heap. The great concresteel viaduct heaved beneath me as though it had no solidity at all, and a dizzy vortex of the night swirled into my brain.

"I—I'M sorry," I muttered. "He must have hit me harder than I thought. I—I'll get up—" I pushed hands down to shove myself up and my hands were pushing against something too soft to be the deck of the viaduct.

"He hit you hard," Rade Hallam's voice was saying, "and you'd gone through too much last night for even a lad of your brawn—"

Last night! My eyelids flew open. Sunlight brightened the ceiling over me, lay on unpainted, sheet-aludur walls. The worn, anxious face of Captain Hallam came toward me.

"How are you feeling, Toom," he asked, "after your sleep?" He was in threadbare breeches and white shirt open about his corded neck. "Ready for breakfast?"

I sat, the coverlet falling from my torso. I was naked, the tavern's sweat and grime bathed from me. "For three breakfasts." I grinned. "But where am I and how did I get here?"

"You are in my home," Hallam responded, "such as it is. Atna carried you here. He wishes me to beg your pardon."

"Taurus!" I grunted. "He thought I was a gangman carrying you off, sir." But I winced inwardly, thinking of what I would be now had the Martian opened his hand when he held me dangling over that three-hundred foot drop. "Besides, I hit him first."

"So he's told me, and that took rare courage. You're a fit son of Toom Gillis."

"I have tried to be, sir." I swung my legs over the edge of the bed. It was not actually a bed, but a metal hammock such as equip the crew-quarters of the spaceships, sprung vertically and sidewise. Another swung on the opposite side of the tiny chamber. This had been broken and welded in a half-dozen places. A single chair, similarly repaired, completed the room's furnishings.

"You could have no better model, Toom," Hallam mused as I rose, "than your father."

"Only one, sir. Yourself, who were his."

The bruise on my chest ached dully, but my head was clear again, and I was aware of a tingling eagerness not unlike that which I had felt when about to enter for the first time the common room of the Tavern of the Seven Pleiades.

Perhaps the singing I heard beyond the door had something to do with that.

Behind the Moon, a million miles.

Lovely Lady, I dream of thee.

Black space is bridged by your mem'ried smiles

And the stars bring your kisses to me....

"There are your clothes." Hallam indicated a neat pile on the

chair-seat. "Mona was up before daybreak, washing and mending

them."

"All this is very embarrassing, sir. I have done nothing to deserve it."

"Except to bring a ray of light into the blackest hour of one who too long has been exiled to the outer darkness." He sighed deeply and his hand rested briefly on my shoulder, then his tones were those of the genial host again. "You've made a swift job of dressing, son. Come along. We're rather primitive here, and you'll have to finish up outside."

THE room into which I followed him was not much larger than

that where I had slept, but a miracle of compact stowage had been

accomplished there. Mona was making herself busy. Cheeks flushed

with the heat from some peculiar contrivance that passed for a

stove—a box-like construction of metal that gave off the

most savory odors. A brightly colored garment clinging to her

lissome curves, Mona presented a picture from which I had not the

least wish to avert my gaze.

She turned, and her brown eyes were sparkling.

"A fine time to say good morning." She tucked a strand of hair away from her high forehead, and I observed that though her hand was narrow and long and carefully tended there were small scratches on it, and a burn, and a roughness that showed they were not unused to hard work. "The noon time-sign has just flashed. You have slept long, Mr. Gillis. Have you slept well?"

"Except for dreams of a girl's pert face, exceeding well, I thank you. And I thank you also for making clothing again of my rags—"

She turned back to her cooking in evident confusion, and beneath the silky down on the back of her neck a redness crept. She moved a pot and I was surprised to see the orange flare of fire come out of a hole it had covered.

"I told you we were primitive." Rade Hallam answered my puzzlement. "We have reverted to the stove of our ancestors for our cooking."

A tank suspended on the wall opposite. The stove was furnished with a wash basin. As I made use of it, I realized that this, like the bunk inside, had been neatly repaired; and this was true of everything about the place.

By the time I had dried myself, the table was steaming with the dishes set out upon it, and three chairs were drawn up. I wondered what had become of Atna.

I can't recall ever downing so tasty a meal, nor with pleasanter companions. Mona was too busy seeing that our plates were kept replenished to do much talking, but under Hallam's shrewd probing I found myself giving a pretty complete account of all I had gone through from the time, five years ago, the board money Dad had paid for me gave out, and Mother Gore turned me loose on my own.

"In other words," he said when I was done, "because of me you are once more penniless and homeless."

"I've always found something. You shouldn't see it so, sir...."

"How would you like, Toom," Hallam leaned forward, "to remain here with us?" His upraised hand stopped my protest at my lips. "I shall expect to be paid for what little I offer—in labor. In honest truth, I need very much the aid of someone I can trust."

"You can trust me, sir, but—"

"But you are puzzled to know what work I could have for you. Come." He rose. "And I will show you."

I rose too, and then wondered why he did not move but looked at Mona, who set down the pile of dishes she had gathered, and picked up a bucket of refuse and went out with it through one of the three doors from this room.

"We have to take certain precautions," Hallam explained.

Mona came back in, her bucket emptied, and said, "All clear, Uncle." He nodded, and led me through the door.

I stopped again, outside, and gaped with astonishment. We were at the bottom of a pit whose sloping roughly circular sides were a reddish-brown jumble of rusted metal; durasteel and aludur and chromenic, smashed and twisted beyond any possible use.

I saw a crushed stratocar with its vanes gone. I saw the broken arm of a motile derrick, and a ruptured man-shell. The jagged top rampart of the pit rose a hundred feet above me. The pit was hollowed out, it dawned on me, into the mountain of junk that rises north of the spaceport, a decade's gathering of refuse from the machine shops and factories hereabout.

"I—that is where you got the furnishings of your hut," I blurted.

"And the hut itself. Look."

I TURNED, and gaped anew. I had just stepped out of a cheery

room. Now I stared at a mound of smaller refuse rising from the

bottom of the pit like a fumerole from within a volcano's

crater.

"Cleverly concealed, Toom, is it not?" There was an odd sort of pride in Hallam's tone. "Even from a plane would anyone suspect that there is a home here, and people living within it? If you have the charity to call it living.... Come, I shall show you something even more cleverly concealed."

He started off. I anticipated climbing the man-made hill. But when Hallam had reached the foot of the slope he ducked down and crawled between the legs of a lop-sided inverted V formed by two crisscrossed girders whose rivets had caught, apparently by accident, in one another.

The skewed V was merely the entrance to a passage burrowing into the heart of the junk-mountain. It debouched into a cavern, its roof more than fifty yards high, the space between its back-sloping walls even greater.

Roof and walls were of the same metal conglomerate as the sides of the pit from which we had come. Sunrays sifting down through chinks in the amazing ceiling made a dim twilight.

"This was a pit like the other," Hallam said. "Atna and I covered it over one night, when we found a motile derrick unguarded. But what do you think of that?"

That was a sleek, ovoid bulk looming in the center of the cavern. A spaceship, by all that was holy! Old-fashioned, tiny when one thought of the modern monsters resting in their cradles a short mile away, but an authentic spaceship.

"What—what can I think?" I stuttered. "I—How—?"

"How came she here? They dumped her here, that's how—in this boneyard. Her plates were buckled, her rocket-tubes were either pitted or burst. Her lock-doors were sprung. Billions of miles she had sped through the void, lacing space with the golden glow of her blasts, carrying man's empire to the very stars. One of the first to land on Mars she was, and the very first to fly sunward to Venus, and they denied her even decent burial."

Rade Hallam's eyes were turned to the craft, his face in the dusk seeming to shine with an inner light. "They cast her on the dung-heap to rot, and they cast me to perdition—we who once combed the comet's hair with our teeth." He turned and spoke to the ship. "But we found each other, you and I, who had blazed the spaceways for them while they squirmed in their high-chairs with fear at the very thought of the perils we dared. But I found you again. We brought youth to each other, and courage, and soon the Earth to which they cling will cringe from the blazing gases of our contempt. We shall need no Song of the Spacemen to bring us luck, for we shall forge our own luck—you and I."

I got the whole story, the thrills coursing my spine. Grounded. Broken. Life dead within him as surely as though the knife that had cut the sunburst from his breast had twisted in his heart instead, Rade Hallam had come upon the rusted skeleton of the very ship on which first he had leaped into space. He had rebuilt her, through what Gargantuan labors, what infinite connivings, I could only guess, and in rebuilding her he had rebuilt himself.

I was proud, in that moment, that in my veins too, ran the blood of one who had blazed the spaceways. Such a man had my father been.

"WELL, Toom?" Hallam asked when we'd finished our tour of the

Polaris. He'd switched on the cold-light in the

control-cabin and everywhere was the glitter of polished metal

and the gleam of immaculate glass.

"She looks trim, sir." By the effervescence in my blood my eyes too must have been sparkling. "As ready for flight as ship ever was."

"No." The proud smile faded from his face. "We still lack two things."

"Fuel, sir?"

"She has enough of both liquid oxygen and hydrogen to take her to Jupiter and back, and she is provisioned for such a journey. Atna, laboring these six years in the spaceport's supply yards, has proved a very able thief. Outside of this cabin, Polaris is complete."

I looked about, at the great switch-bars, the shining wheels, the arm-thick cable-pipes writhing into the wall, at the instrument serried gauge-board. "I see!" I exclaimed. "There's no star-scope."

Hallam nodded. "There's no star-scope, Toom, and for lack of an instrument that can be held in the palm of a child's hand, Polaris is as blind as a boat without a compass."

"Blinder, sir. The navigators had the stars by which they charted their course, but in space the stars are useless to an astrogator without a 'scope to interpret their message."

"Yes. And Mulvihall's tiny miracle of platinum and fused quartz is not thrown on the junk heaps for me to pick up, nor do any lie around the supply-yard, prey to Atna's deft fingers."

"But you don't need a 'scope for a trip to Venus or Mars, sir," I said eagerly. "If you cast the orbit of your destination on a space-chart, calculate the speed of your ship and her ether-drift and use Taner's formulae for integrating the flux of universal gravity, computing the rotational coefficients of Earth and the planet you aim to reach, you can elevate your takeoff cradle to the precise azimuth required to come within a degree of arc of your planet. That is near enough to make a spiral landing by televisor, and—"

His hand lifted. To strike me for my temerity? It closed on my shoulder instead, and I felt it quiver. "Toom Gillis. Toom! What do you know of ether drift and universal gravity and rotational coefficients? What do you know of spiral landings?"

"I can make one, sir. I swear I can make one, though I've never had my hands on the switchbars of a flyer."

I WAS not boasting, but telling him something that he must

know. "I can cast a world-line as true as any controlman zooming

Space, and calculate a conjunction of ship and planet within a

hairsbreadth. Dad commenced teaching me the rudiments of

astrogation from the moment I could lisp the terms, and no matter

what straits I have been in since his death, I have lost no

opportunity to perfect my knowledge." I thought of how often I

had gone hungry to purchase the needed books and tables.

"Do you hear that?" It was to the ship he spoke, not to me. "When you sent me to the Tavern of the Seven Pleiades in search of the aide I must have because human flesh must have sleep sometimes and rest, in the months of a flight, I had no hope. When those who were there turned their backs on me I knew despair. But you were right and I was wrong. I have brought you one of the two things we lacked, and now I am certain the other will come to us. Our time of waiting is at an end, Polaris. Now indeed I know that."

There was no madness in his voice, but there was perhaps a glimmer of madness in his eyes. It was a divine madness. He was not mad enough, all the same, to take my word for what I knew. "Get over there," he commanded, "and I'll test you out."

I seated myself in the spring-floated controlman's chair "Prepare for blastoff," Hallam barked.

"Prepare for blast-off, sir," I acknowledged. This was a game I'd played many times with Dad. I thumbed buttons, then: "Ready for blast-of, sir."

"Blast-off!"

Down went the proper bar. I watched the gauges. Their pointers of course were still, but I knew what they should be doing. "In free fall," I gasped, at last, as though in truth I were just coming out from under the awful weight of seven miles per second acceleration that had torn Polaris free of Earth's gravity.

"You're headed 2.74 degrees alpha, 9.52 beta, 89.63 gamma," Hallam snapped. "Your speed is twenty-two miles per second. Our objective is 38.65 alpha, 79.34 beta, 2.68 gamma. Hold your speed but lay your course."

"Aye, aye." I played the rocket-tube bars. "On course, sir."

"Make it so, mister," the master snapped, then his voice was soft with approval. "That was well done, Toom."

"Thank you, sir," I said. And then, "But the objective you've given me is in the orbit of no planet, sir. It is somewhere between Mars and Jupiter."

"Exactly," Hallam responded flatly. "In the region of the asteroids. It will be an asteroid, Toom, for which we make when we blast-off, and now you know why I need a star-scope?"

AN asteroid. The man was—Wait! Was it not in the region

of the asteroids the Terra was pithed?

"Meteor five-tenths port, six point two up, headed directly for us!" Hallam yelled. "Quick!" I veered my imaginary course to avoid the danger. And at once Master Hallam was roaring something about an ether-swirl. And so it went.

He drove me until I was limp as the rag I'd flung in Nick Raster's face, until I was trembling and dizzy. Until my palms were rubbed raw with tugging at the switch-bars and my head reeled, and I scarce longer could see the gauges. It was only then that he had me make a spiral landing and signal Done with tubes, to the fuel-hole.

He was exhausted, as I. But he said crisply, "Oh, well done, Toom Gillis! I have known only one controlman better than you, and the name of that one was the same as yours."

Perhaps that, combined with my fatigue, made me a little drunk, for as I unstrapped myself and Hallam switched off the light, I thought I saw the meteor-alarm flash scarlet, its needle swinging to 0.3 starb'd, level. "Look!" I exclaimed, jabbing a finger at it—and it went black.

"What is it, Toom?"

I explained.

Hallam laughed. "We're meeting no meteors yet, lad," he chuckled.

"No, sir. But—but might not the signal have been activated by some listener-ray focused on us?"

I could make him out only dimly in the dark, but I could see him stiffen. "A listener-ray. Can it be that at the very last—But it's gone now. If some police squad had tapped in it would still be focused on us, while they trace us down. It was either some random flash or altogether your imagination."

"Probably my imagination, sir." But I was uneasy. And my uneasiness would not be dispelled.

GRAY dusk filled the pit when we crawled cautiously out from under the inverted V of the girders. At the hut, Mona greeted us with a scolding. I bristled, but Hallam whispered to me that her sharp tongue only showed her relief at our safe return.

After I'd washed up I offered to set the table for her. "You'd do better keeping out of my way." She tossed her rumpled locks. "I have too few dishes to risk their being smashed by any clumsy oaf who comes along."

I grinned. "If that's the way you feel.... But you'll ask me to help you some time and you know what answer you'll get."

"You'll have a beard down to your ankles before I ask you, Toom Gillis," she came back. "And that will be a long time, judging by the smoothness of your skin."

"I'll have you understand, young lady, that—"

"Toom," Hallam interrupted. "Please come over here. I want you to work out a world-line for me. There are a few shortcuts I'd like to—"

He cut off as the door opened to admit Atna.

"Bahss!" the green-faced giant rumbled, "Bahss!" There was excitement in his voice, as he held out to Hallam a little black box. "Bahss, you look what Atna find."

Mona turned, motionless, trembling.

"A star-scope!" Hallam had fumbled the box open, and if ever intonation made a prayer of thanksgiving out of a man's voice, it was then. "A Mulvihall star-scope." I believe that if there had been no light in that room it still would have been bright with the glow in his eyes. "How in the ecliptic did you come by it?"

The Martian shrugged. "Things roll when I climb down pit side, like always, an' I watch for something we can use. I almost at bottom when I see this roll by me. I remember picture you show me, an' I pick up."

Rade Hallam's head lifted his shining eyes to me. "A gift from the Gods of the Void." His voice was hushed. "Toom Gillis, I told you—"

"Uncle," Mona broke in, "the police will be combing the dump for it. They'll find us, and—"

Hallam's lips went white. "Gemini! We've got to get away from here. We've got to leave at once."

"Where? They'll find us anywhere in the city. We can't—"

"Give me two hours and they'll never find us." The words had a clarion ring. "The Antares blasts-off at eight and there will be two ships leaping into Space from Newyork port tonight."

"You mean to—?"

"We're near enough to the spaceport to be covered by the blinding flash of the Antares' blast-off. Our own will not be noted, and once out in Space we'll never be spotted. Come! All of you! We'll have to work quick to get this installed and tested by eight...."

THE shorter hand of the chronometer on the Polaris'

gauge-board was almost on the mark of VIII, the longer lacked

only two spaces of the XII. Master Rade Hallam was strapped in

the controlman's chair, and I lay in the relief man's hammock.

Mona, I knew, was in a similar hammock in the crew quarters, Atan

down in the fuel-hole.

"Suppose the Antares is delayed, sir." I spoke the thought that had been bothering me all the time we had worked feverishly to set the star-scope, "What then?"

"Then our own flash will be seen, as we burst through the roof over us, and the port patrol-ship will follow. They'll have to pith us, Toom. I'll return to Earth vindicated, or I'll not return at all."

His hand trembled and throbbed on the switch-bar; his eyes never flickered from the chronometer. That minute hand had stopped—No. It was still moving. The space between it and the hour-mark had lessened imperceptibly. It was the long second-hand I was watching now, as it swept around the dial.

Twenty seconds to eight. Fifteen. Ten. Five—Now! Hallam's fingers thrust down the switch-bar—

The rocket-tube roar was thunder—A gigantic, invisible weight was forcing me down, down, on the springs of the hammock. It was crushing me. In another instant my blood would burst from my fingertips, my ribs would cave in—

There wasn't anything. There was nothing at all, except the hammer of pain in my arms, my legs, my chest. The triphammer of pain on my skull.

"Toom. Toom Gillis." Rade Hallam's voice. "Toom."

I opened my eyes. Nothing was changed. Nothing at all except—Yes. The clock was changed. The minute hand pointed to three minutes past eight. We'd missed the blast-off then. We were still on Earth—

"We're beyond Earth's atmosphere, Toom," I heard. "We're in free fall, in Space."

I managed to straggle up to a sitting posture. "In free fall—" I repeated stupidly, still dazed. "But—"

"But you have normal weight? I've switched on the automatic gravity-compensators. Come here, mister. I want you to take the controls while I go to see how Mona has stood the acceleration." He was unfastening the straps that now would no longer be needed, and I saw how blue his fingertips were, how wan his face. He had not stood it any too well himself. "There's the Antares." He nodded to the four leaf clover of the televisor screen as I took the chair he vacated.

There she was indeed, black ball against the star-dusted black velvet of Space. I gasped at the sight of that incredible panoply of stars, more brilliant, more dazzling, than any Earthbound human can conceive. And I gasped again when I realized that the blue streamer scything the skies was the Antares' wake of burned but hot gases.

"Master Hallam!" I jabbed my forefinger at it. "They'll trail us by ours. You forgot—"

"I forgot nothing, mister," he snapped. "I shut off our rocket-tubes the instant we came free of Earth pull. We are leaving no trail, and we'll leave none till we're far enough out that we'll not be spied by Earth, or by the Antares, whose course we're angling from, as you see."

TAURUS! He'd kept consciousness to do that with his

weight—the weight of every cell of him, multiplied over

three hundred times! And I'd dared to comment on the blueness of

his finger tips, the wanness of his face, I who'd passed out

completely before our acceleration had reached more than ten or

twenty times Earth gravity!

"You'll use the tubes, mister, only if necessary to dodge a meteor."

I heard his feet thud across the durasteel floor and I heard the durasteel door clang shut. Less than twenty-four hours ago I had called myself a fool for dreaming that some day in some distant future I might sit in a controlman's chair. Now here I was.

It was a heady wine, this realization. It bubbled in my brain, and fizzed in my veins, though all there was for me to do was to sit there and let the sweet ship run. Spying Earth's sphere in the lower limb of the televisor, I thumbed my nose at her orb.

As if in rebuke, Sun's mighty blaze flared from behind Terra, and smote me full in the eyes!

I didn't look into that lower visor-screen again till I'd groped for and found the dark goggles that hung on a hook beside it. And even after that I looked at it only when needs be. I'd learned that Space was no place for trifling, nor for an instant's relaxation.

We settled down quickly into routine. At first Hallam hovered over me, scanning every move I made; but after he thought it prudent to step up Polaris to an even thirty-miles-per-second gait, we stood watch and watch. Atna, I believe, slept hardly at all, below in the fuel-hole.

Those first few Earth-days Mona spent many hours in the control-cabin, ohing and oohing over the countless wonders unfolding on the visor screens. But after awhile this palled on her and if I wanted to visit with her I had to seek her out in the living quarters. This I did right often, and for the life of me I do not know why. Our conversation might begin pleasantly enough, but almost invariably it ended in bickering, and a flare of temper. She would flee into the cubbyhole where her hammock was sprang, and I to stare hot-eyed at Rade Hallam in the controlman's chair, swearing silently that I would never speak to her again.

And then, when my next trick was ending her voice would follow the Master in to me singing sometimes that first song I'd heard from her:

Behind the Moon, a million miles...

and sometimes another, and I'd go in to her like a weak-willed ninny.

WHEN we'd been out about two months, Rade Hallam found me

gazing intently into the televisor, my brows knitted. "What is

it, Toom?" he asked quietly.

"I thought I saw—There it is again!" I pointed. "Look! That dark speck transiting Procyon. I caught it against Sirius a moment ago. I'd say it was a spaceship, only—"

"Only there should be no spaceships this far past Mars. I don't see it, lad. Are you sure?"

"Dead sure. If it holds its course we ought to catch it in a moment clear against the Sun's disk."

He bent to the screen. There was something feral about him, something—deadly.

"Maybe it was a meteor I saw," I ventured. "But it seemed too sleek for that, and it would have to be a cursed big meteor for me to make it out while it was still too far away to activate the alarm."

"I discern nothing." Hallam straightened. "Your imagination must have been working overtime again."

"It wasn't imagination, sir," I insisted. "I saw something.—Look, sir. Would there be reason for anyone to follow us?"

"There might be. There might well be." His countenance was a mask, his eyes expressionless. "But how could anyone follow us when no one could possibly know we're out here?" He seemed to be asking the question of himself, yet I might have answered him if Mona had not appeared in the doorway.

"Toom," she said, "I'll be pithed if I'll hang over a hot range broiling frozen chops and then have you hang around in here gossiping till they're spoiled."

"You'd better go, lad," Hallam advised me. "Or she'll be calling me a heartless old slave-driver again. I—"

"Uncle!" Mona cried. "You—you..." Her face flared as red as a popquin.

"Out!" Hallam shouted. "Both of you. I'll not be bedeviled by you young rapscallions. Out, before I have Atna put you both in the brig."

I didn't ask Mona about that slave-driver business until I had eaten. When I did she didn't wait even to bicker but darted into her cubby and slammed its door.

Scratching my head at the vagaries of the eternal feminine, I wandered back into the control-cabin. "Seen anything more out of the ordinary, sir?"

"No, Toom," Hallam answered. He looked even older, grimmer and more leathery, than ever. "I haven't. But I've been doing a lot of thinking and I've decided that I've been damnably unfair to you."

"Unfair, sir?"

"Yes. Come over here, Toom. I'm going to tell you where we're headed and why."

YOU must remember (Rade Hallam began, his brooding gaze fixed on the televisor) that up to five years ago the I.B.C. regulations for space-flight were far less stringent than they are now. One could clear port for "destination indeterminate," and follow one's own bent in the void.

Thus it was possible for the Terra to blast-off on a secret mission. And the mission on which she blasted-off, that fatal trip, was indeed secret. So far as I was aware (I thought he laid undue emphasis on the phrase) only two men ever knew what it was; on the Terra only myself. I sealed the controls after setting our course, leaving unconcealed and free only sufficient switch-bars to cope with emergencies.

The man whose secret our destination really was, was Mona's father, Jare Lloyd, the explorer. The astronaut who on this very Polaris first drove sunward to Venus. The master rocketeer who—after he had taught me all I know of spacemanship and turned over Polaris' command to me—with the Aldebaran put Earth's ball farther under his keel than man had ever been, farther than man has since been.

You think Jare Lloyd died sixteen years ago, when the fuel-tanks of the Aldebaran exploded, off the Moon. Only one of her crew was believed to have survived.

Jare Lloyd did not die off the Moon. Terribly burned, his body a wreck, his indomitable spirit brought him back to Earth in a man-shell. When that journey ended, his mind was shattered and all that was left to him was some unconquerable instinct that led him crawling through a black and blinding storm, to his wife and the girl-babe he had never seen.

It was Atna who heard a faint scratching on the door, beneath the howling of the storm, and carried Lloyd in. It was Naomi Lloyd who hid his return lest he be taken from her to some institution, and who nursed his broken body back to some semblance of health. But it was ten years before her tender care brought light again into his brain.

The first I knew of all this was when Atna brought me a message that Naomi Lloyd wanted me to come to her on a matter of importance. I had visited her once, and my reception had been such that I had never visited her again. I found out why, after a decade, when she led me into an inner room and showed me who had really sent for me.

WHEN I recovered from the shock of finding Jare Lloyd again,

and the greater shock of finding him as he was, he told me how,

on that last voyage of his, he had saved an aged Martian from

death in the tail-embrace of a stoora. In gratitude, the

Martian had related to him a legend of an Island in the

Sky, a yellow island, where their ancients had buried

a store of the "heavy stones" for Mars' scanty supply of which

Earthmen seemed so eager.

Now the "heavy stones" Jare knew to be pebbles of that almost weird element hellenium without which half the syntheses that have made our modern world what it is would be impossible. A grain was worth somewhere around a hundred dollars; any considerable amount of it a tremendous fortune. Jare knew also that long before our own ancestors crawled up out of the steaming brine, Martians were traveling space, though since they have degenerated to hazy-minded savages. Thus it was altogether possible that they might have cached hellenium on some asteroid.

Being Jare Lloyd, he had to go and find that yellow asteroid and see if the legend he'd heard was true, though no human but he had ever yet dared that region where the fragments of some shattered planet stream in their vast circle about the Sun. He went back to Aldebaran and gave the order to blast-off. He gave the course to his controlman and sat down at his desk to put down in his diary what he'd heard.

He'd written only a few lines when a deputation from the crew was trampling in. They'd noted by the wheeling of the stars that the ship was venturing farther into unknown space, and they were on the verge of mutiny.

Jare sensed they were in an ugly mood, but he cajoled them into giving him an hour for his answer. Before that hour had ended they were in no condition to trouble him further.

Jare Lloyd had donned the helmet of a space-suit and spilled into the compressors of the air-supply a half-gallon of the ether-dyne that he carried on board for the collection of other-planetary animals for the zoos. His mutinous crew were in a state of suspended animation till he chose to wake them.

When Jare went back to his desk, his diary was gone. Some one of the crew had taken it. But he recalled that all he had written was: "I've got track of an almost unbelievable treasure..." and so he laughed it off, and went to the controls.

He found the yellow asteroid, spotted the hellenium cache, but with his fuel-hole untended, he could not manage the delicate maneuvers required for landing on so small a body. So he drove the Aldebaran Earthward, and when he'd passed Mars again he reawakened his crew, and they did not know nigh two months were missing out of their lives. He told them that he'd yielded to their demands, and they cheered him. He wrote no more for a spy to read, but mentally noted the position of the yellow asteroid and its orbit, against his return with a crew he could trust.

Then had come the fuel-hole explosion off the Moon, and ten years of blankness.

Now Jare's mind was back, and clear as though those ten years were a single night the details of position and orbit of the yellow asteroid were in it, but he knew he never could fly again. Would I retrieve the treasure for him, so that he might die knowing that Naomi, and Mona, his daughter, would have some repayment for the privation and distress he had brought upon them?

There was only one answer I could make to that.

It had to be done in inviolate secrecy, because of the Law of the Triplanetary Union that all treasure-trove of space is wholly the property of the planet whose native finds it, save for a beggarly one percent to the finder. That there was another reason for secrecy we were not then aware, but we were soon to find out.

I was to find out....

THE Terra was cleared and I was about to mount her and

order the last lock-port closed, when Atna appeared, crying my

name; little Mona in his arms. He'd taken the child to witness an

airpolo game, had returned home to find her mother slain, burned

by a heat-gun, and Jare—tortured to death!

There could be only one motive for the crime—to extract from Lloyd the location of the treasure. There was only one man who could have that motive, who could know that there was a treasure—

Nick Raster, who had lost his arm and eye in the Aldebaran explosion. Who was thought to be the only survivor of Jare Lloyd's last voyage. Who must have been the one to steal Jare's diary. I knew that, but there was nothing I could do about it. I had no proof, and even if I had, to accuse him would do Naomi and Jare no good and would rob Mona. All I could do was send Atna with the child to a safe place, and blast-off.

How Raster had got wind of Lloyd's existence I did not know, but I guessed that it might have been somehow through me. If that were so he might well have planted a spy on board the Terra. I determined to trust no one. I kept our goal to myself, sealed the controls—but I've told you about that.

What I haven't told you is that because of that very sealing of the controls your father died, and all the crew of the Terra save for me.

The way that came about, was this...

(Once more Rade Hallam paused, and I saw that he was gray with the long strain of talking, and with the greater strain of remembering. I knew that I should make him stop, but I could not bring myself to, who was about to hear how my father met his end.)

We found the yellow asteroid (he commenced again) exactly where Jare Lloyd's data and my calculations placed it, after as uneventful a voyage, one as free of meteors and swirls, as ever man made in space. Once indeed, I had had the notion that someone had been tampering with the seals I had placed on the controls, but Toom Gillis—the other Toom Gillis—had convinced me I was wrong.

I did not land the Terra on the tiny planet, but blanked the televisor and had Toom hover her some twenty thousand miles off, while I made the rest of the journey in a man-shell. That way no one would know what I did after I landed, or what I brought back with me.

The cache of hellenium was there. Some instinct tore my eyes from the cairn, and up to the Terra. I was just in time to see the black projectile of a meteor lancing for her hull, just in time to see her rocket tubes flare as, warned by the alarm, Toom called on them to dodge it.

THEY were the wrong tubes! The ship leaped toward the meteor

instead of away from it. The flying rock struck, and my sweet

craft was pithed, and out of the great rent in her hull I saw the

tiny specks spill that were the men I'd left in her, and I saw

the air puff out of her.

There had been a spy on board. He had attempted to open the seals and discover on what course the controls were set. Once he knew that, he undoubtedly would have contrived an accidental-seeming death for me and returned to Earth with his information. He hadn't succeeded, but in making it he had somehow crossed the connections so that when Toom tried to escape the meteor he had sent the Terra to her death.

And I was marooned there, alone on a spinning yellow rock in the vastness of empty space. I think I went mad for a while.

When I came to myself again, what I had to do was as clear and cold and definite in my mind as the fused-quartz prism of a star-scope. I would make for Mars in my man-shell. I had enough fuel, and rations enough, for that; just enough. I could take no ounce of surplus weight with me, but that did not matter. The hellenium had waited there a matter of a few million years, it would wait there another year or two till I returned. And nothing would keep me from returning.

I did reach Mars. And from Mars I was sent back to Earth in irons, to be tried by the I.B.C. for losing my ship. The rest you know or can guess.

And that is why (he finished) there could be someone following us.

Remember the meteor-alarm flashing, down there under the junk mountain, as though a listener-ray might have been focused on our talk—and shut off, just as we ended our conversation. I didn't want to believe it at the time. But I haven't forgotten... If a police-squad had been listening-in on us we'd never have gotten away, as I said at the time. But suppose it were not? Suppose it were—Nick Raster or a spy of his! Suppose the almost incredible good luck of Atna's finding the star-scope was not luck at all, but arranged by Raster. So as to enable us to embark—and lead him to the treasure he's waited sixteen years to trace!

IT WAS nearly two more months before we at last reached the orbit-zone of the asteroids. During all this time, though we watched very carefully, we never again saw any hint that we were not the only living beings in all the empty immensity that stretched between us and Mars. Hallam decided that his apprehensions might be baseless; and I hoped that he was right.

Nevertheless it was entirely possible that some space-ship was keeping us in view without herself coming within range of our rather antiquated instruments.

Mona did not take my desertion in good part. I never heard her singing now. When we were together at meals she spoke to me only when necessary, and even then addressed me as Mr. Gillis.

Altogether the fine joy of our adventure was gone. But I was excited enough when, tossing sleepless on my hammock I heard Master Hallam say, very quietly, "There it is, Toom."

I got to the 'visor in a single bound. There it was, indeed. A jagged rock, not ten thousand miles away. Golden with the sun's rays. Two or three miles in diameter. A wee thing to have come over three hundred million miles to find.

"Gemini, sir!" I blurted. "You've hit it right on the nose. That's astrogation!"

The asteroid was turning, slowly, but quite perceptibly. Something black showed against it, something malformed and black, not on its surface but perhaps a thousand miles away from it and circling with it. "It has a satellite, sir," I mumbled.

"A satellite," I heard Rade Hallam whisper. "Look a little more closely at that satellite, Toom."

I did. I saw that the black object was a spaceship. A pithed spaceship! And I saw that it had satellites of its own, black specks....

"The Terra."

"The Terra, and her crew. The gravity of the tiny planet not quite enough to draw them to its surface, but strong enough to hold them. They journey eternally with it on its eternal journey through space. One of those specks is your father, lad."

What my thoughts, my emotions, were in the next few minutes I hope I shall be excused from phrasing.

At last, slowly, majestically, the dead ship and the dead men moved behind the asteroid and were hidden.

It was just that moment Mona chose to enter. "What's happened, Uncle? I felt the forward rocket-tubes blast to stop the ship—Oh!" She'd come near enough to see the televisor. "We're there! We've found it!"

"We have found it," Hallam answered.

"And—and that dark spot, there, is that the treasure?"

"It is the treasure."

"Are you going to land the Polaris, or—"

"I'm going to land her. Stand by."

His hands moved on the switchbars. He brought us nearer, nearer the asteroid, circling us with her slow rotation. The Polaris drifted down, light as thistledown. Light as thistledown she settled on the saffron rock, not a mile from the dark mound of pebbles.

"Done with tubes," Master Hallam signaled to Atna in the fuel-hole. "Report to control-cabin."

Mona was dancing, vibrant.

"Break out the canvas bags I had you sew up, Mona," Hallam directed her, "while Toom and Atna and I get into space-suits."

"You and Atna and—Aren't I going out too, Uncle?" The girl's face fell. "After coming all this way—?"

"You can carry the least load of us four, and someone has to operate the air-locks. You—"

"Pardon me, sir," I interrupted. "May I remain aboard?"

"Toom!" Master Hallam wheeled to me. "What's this? Do you think that just to please Mona I'm going to permit—"

"It's not that, sir. I have a real, an imperative reason for my request, and what's more, I strongly urge that you adhere to your original intention of having Mona remain, too."

"I won't." She stamped her foot. "If he stays I'm going out. I wouldn't stay here with him if he was—"

"Quiet, child," Hallam admonished her. He was studying me. "Do you want to tell me the reason for your request?"

"I'd rather not, sir," I replied, my eyes sliding to Mona, and back again to his. "But I wish you would grant it."

"Very well," he turned to the girl. "Mona. You will stay too."

"I will not." She was white-faced, taut-lipped. "I swear I will not unless you put me in chains. I'm going out there with you."

Rade Hallam shrugged. "It seems I'm not master of my own ship. But I'm too weary to argue. Break out the bags and then get into a space-suit."

It didn't take the three of them long to get ready. I let them out through the airlock, then returned to the control-cabin.

WITHIN the ship the space-suits had made them grotesque

enough; out there they were incredible colossi striding across a

nightmare landscape. The horizon of this small world was a bare

four miles away, but my vision insisted on making it the thirty

to forty it would be on Earth, and magnifying them in proportion.

Weighted though their shoes were, the asteroid's gravity was so

infinitesimal that every step they took lifted them bodily, and

their gait was a buoyant hopping.

They reached the cairn of hellenium, bent to it and started filling their bags. A monstrous shadow blackened them! Before they could stir, a spaceship half again the size of Polaris was settling on the plain! Off to one side, its landing place made the apex of an equilateral triangle with Polaris and the cairn. My three friends started bounding toward me. A scarlet streak spat from the stranger ship, puffed yellow dust from the plain right in front of them. The warning was sufficient. They halted—waited while an opening lock-door slitted the silver side of the newcomer, and two men in space-suits climbed out.

By the stature of the leader, by the limp, empty way the left sleeve of his suit hung, I knew he was Nick Raster. The gloved hands of both clutched heat-guns as they stalked toward the fear-frozen trio. In their very posture there was ruthless menace—And then the two men were shriveling wisps of incandescence in the blue haze that streaked from Polaris and caught them square in its torrid blast.

I had not been gaping idly. I had been twirling a certain wheel, thrusting down a certain switch-bar, whose functions were very different now from that for which they had been intended.

My long hours in the hold of the Polaris, laboring with the tools with which earlier Hallam and Atna had reconditioned her, had borne fruit.

A twitch at the wheel lifted that blazing blast to the inside door of the pirate spaceship's lock. The metal glowed red—white—burst outward in a blinding coruscation of sparks. Burst outward with pressure of the air within, and I knew there was no life within her, no life at all.

I pulled up the switch-bar and saw the flame die down.

"ALL I did, sir." I explained when the hellenium was

safely loaded, "was to install additional pipes to the swiveled

rocket-tubes on each flank of the ship. Through these pipes the

whole pressure of the fuel-tanks could be delivered, pressure

sufficient to send a blast a distance I hoped would be enough to

protect you. No enemy ship would attack us before we

landed, because they had to keep out of sight till we located the

asteroid."

"So that is what you were about all the time I thought you were avoiding me."

This was Mona. "Toom. Toom, darling. Why didn't you tell me? I—I was so hurt. I—I cried myself to sleep, every night-watch, and—"

"You did!" Somehow my arms were around her. Somehow we were alone in the control-cabin. Not that either of us realized it, busied as we were with realizing something infinitely more important.

After all the hellenium was loaded, a man-shell visit by Rade Hallam to the Terra's skeleton enabled him to fetch away sufficient of her control fittings to prove to the I.B.C. his innocence of culpability in her loss. As all the world knows, his sunburst was restored to him, with full seniority. As far as the world knows, that was the sole reason for the flight of Polaris.

We left Dad's body, and those of the others, as they were. There are no worms in space, no corruption. Neither Hallam nor I could think of fitter burial for rocketeers.

In a gesture at making amends for the injustice done her master, the I.B.C. authorized, ex post facto, Polaris' voyage, and predated the restoration of Hallam's commission to the time of her blast-off. Which made it rather nice for me, since they then could not ignore my work as his controlman. They called it service as a space-cadet, and it gave me well over the required mileage to entitle me to my golden sunburst.

Nick Raster is a heap of charred ashes on a yellow asteroid three hundred million miles from Newyork Spaceport, but the Tavern of the Seven Pleiades is flaring and riotous with a Zanting. They are lined three deep at the bar, the bronzed rocketeers, and the tables are jammed with them. A Zanting like never has been held, this, for this night there is a woman at one of the tables, a slender girl with a pert, impudent face who has voyaged farther than any of them in space, and thus has more right than any of them to be here.

The men of the void are standing, and their glinting glasses are lifted high above their proud heads. The Song of the Spacemen has been called for. Their feet thunder in its first cadence-stamp, thunder in the second, and atop the table at which Mona stands, Master Rade Hallam raises a quart mug of greenwine to his lips.

A third time the feet of the spacemen thunder and, beside Master Hallam, I raise my own mug to my mouth. On the fourth crash I start to drink.

The fiery liquid sears its way down my gullet. My brain is reeling with the fumes and my lungs are bursting.

The song breaks into an ear-splitting roar as Rade Hallam holds his mug out, inverted, and I hold out mine, and from neither spills a single drop of greenwine.

We smash our mugs to a hundred shattered shards. The tavern is a sea of faces and of upraised arms, a storm of sound surging about me, battering at me. But for me one face stands out clear, and one high, sweet voice, crying, "You will come back! You will always come back, my husband, to me."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.