RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

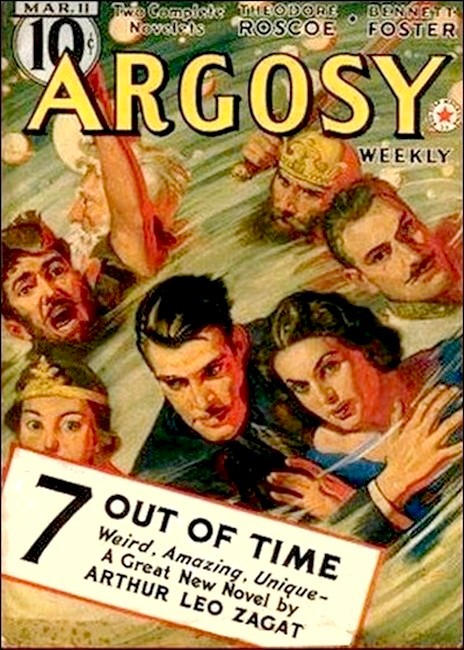

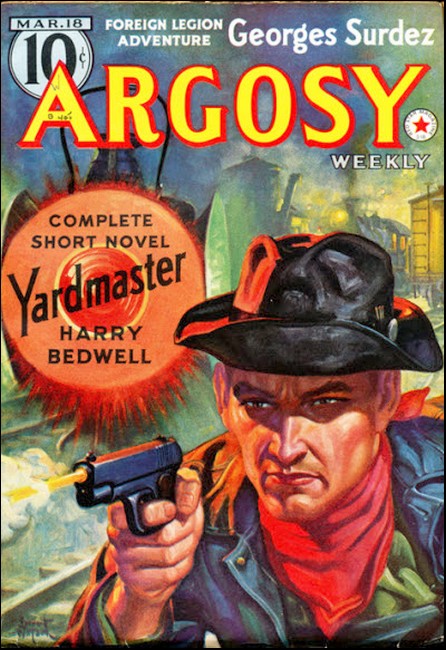

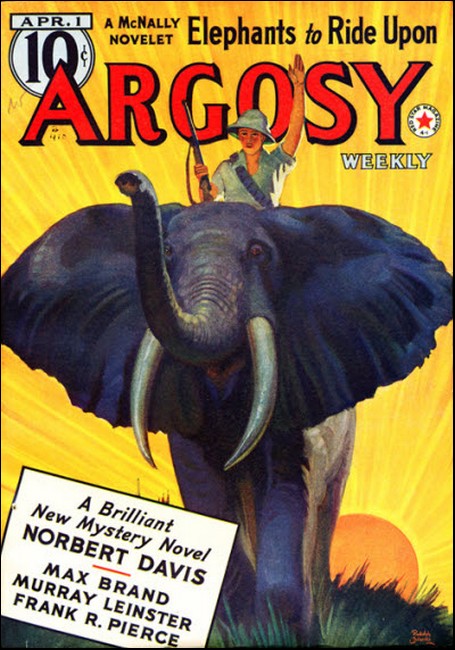

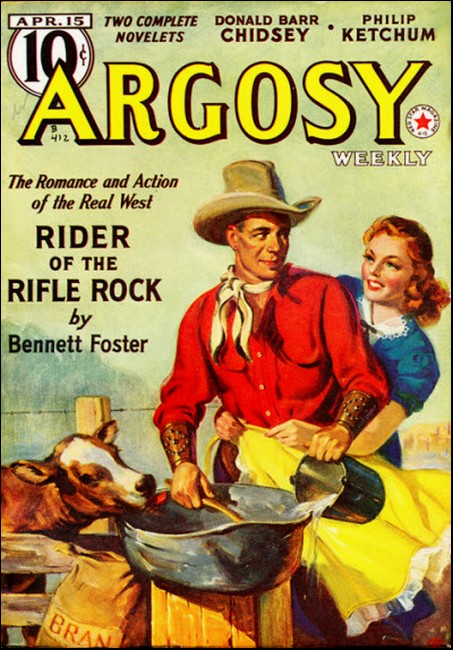

Argosy, 11 March 1939, with first part of "Seven Out of Time"

Here is John March's amazing search for the girt he loved and had never seen; how, summoned by the whisper of a whirl of dust, he stepped beyond the boundaries of time and met the masters of the other world. Beginning a great new fantastic novel by the author of "Drink We Deep"

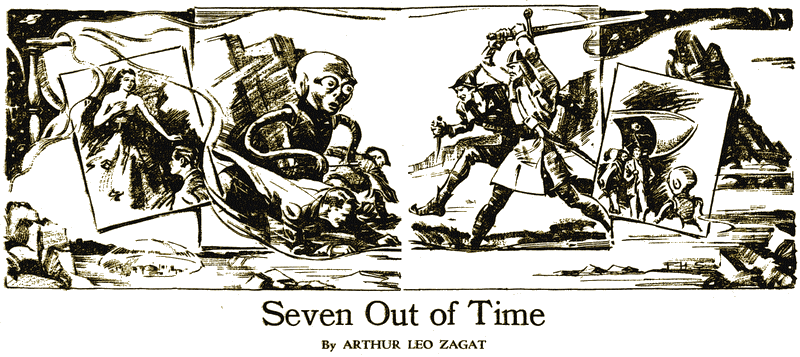

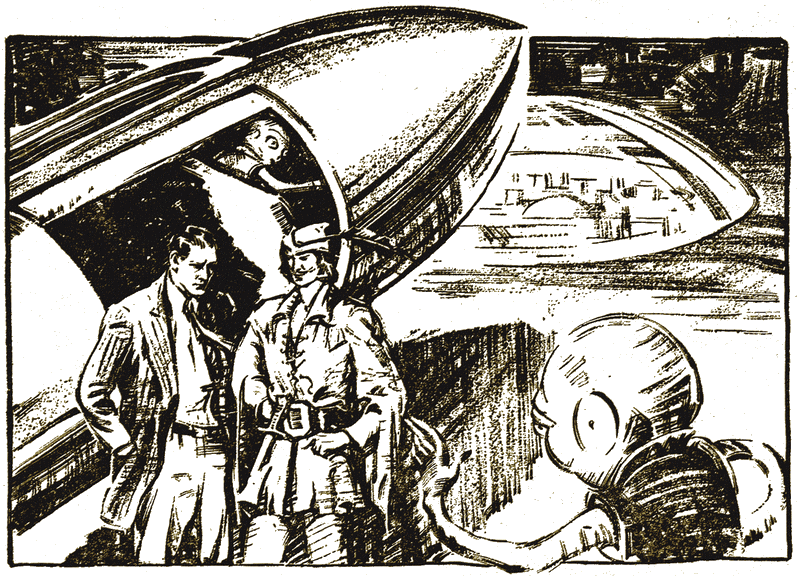

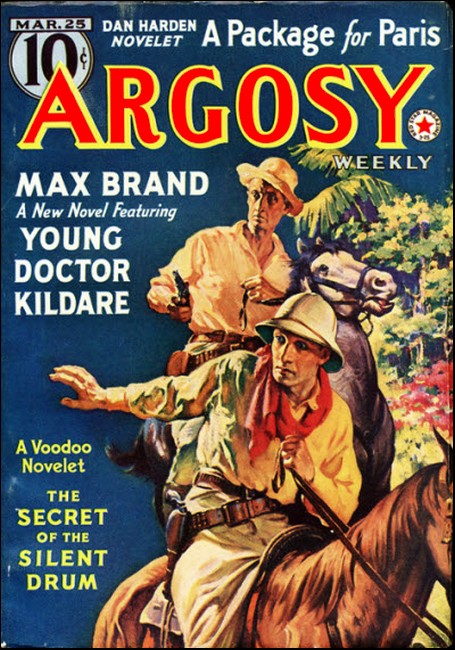

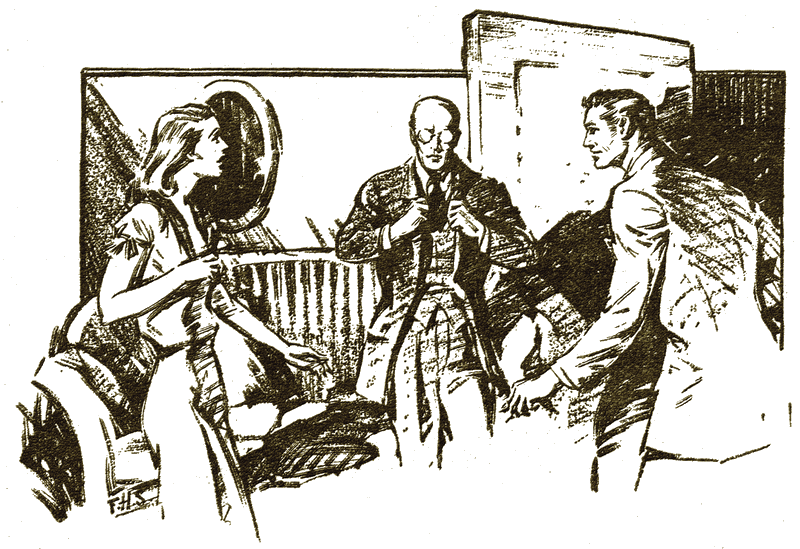

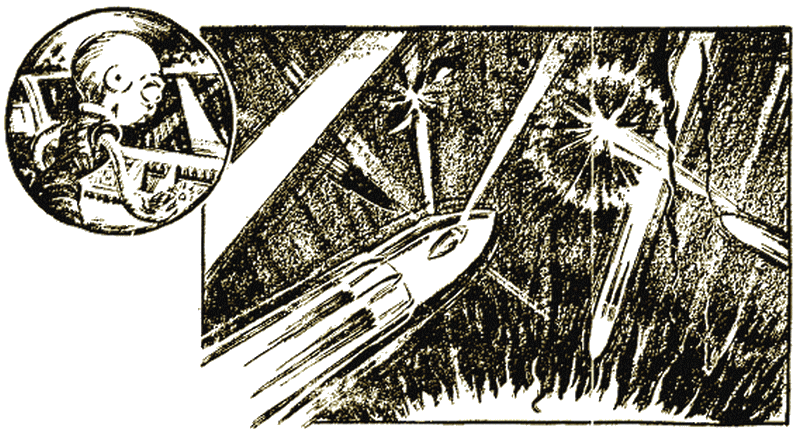

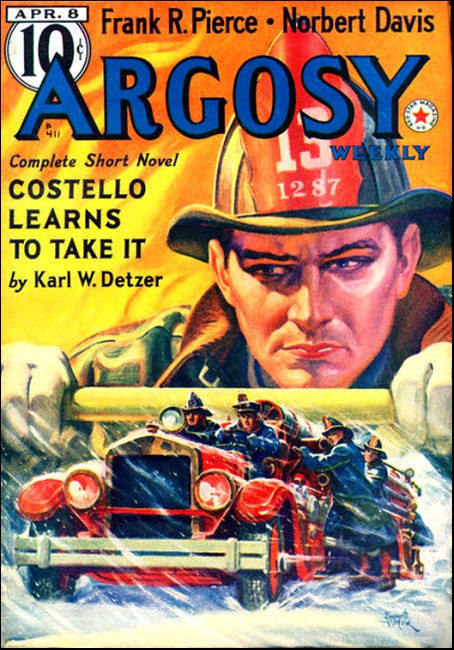

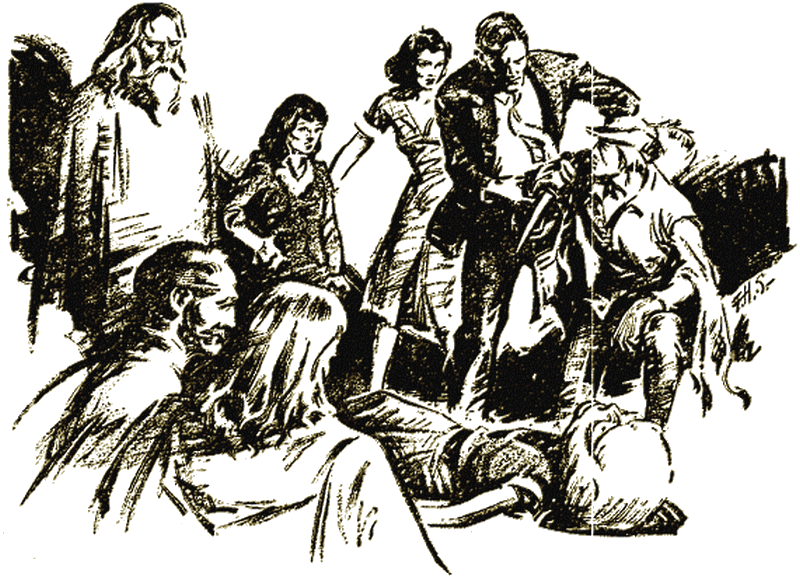

This vintage science fiction classic was originally published as a 6-part serial novel in Argosy in 1939. Each part began with an illustrated headpiece. Parts II, III, IV and V were preceded by a synopsis of the events described in the preceding parts; Part VI was printed without a synopsis.

This RGL edition of Seven Out of Time contains the text of the serial, the four synopses, the six illustrations printed in Argosy, and the covers of the issues of the magazine in which the novel appeared. Five of the illustrations have been moved to the places in the text to which they refer.

A revised edition of Seven Out of Time was published in book form by Fantasy Press, Pennylvania, in 1949. The revisions included textual changes and re-chapterisation. Whereas the serial consists of 27 chapters, the book contains 28, most of them renamed. Here are the two tables of contents for comparison.

| Chapter Title in Serial | Chapter Title in Book |

| I. The Graven Snake | 1. Time Is of the Essence |

| II. Whispering Whirl of Dust | 2. The Portrait of Evelyn Rand |

| III. The Portrait and the Guide | 3. Safari to Brooklyn |

| IV. Address of a Mystery | 4. Forman Street |

| V. Achronos Astaris | 5. The Riddles of Achronos Astaris |

| VI. Colossus | 6. A Sky Too Low, A Fear Too Great |

| VII. Shape of Men to Come | 7. The Empty Shape of a Man |

| VIII. Summoned to Adalon | 8. Adalon, City Of Dread |

| IX. "More Merciful the Gallows' Drop" | 9. More Merciful Is the Gallows' Drop |

| X. House of the Planets | 10. Some Incredible Otherwhere |

| XI. Evelyn Rand | 11. The Scent of Dreams |

| XII. A Matter of Time | 12. Walk Into My Parlor |

| XIII. Lottery of Doom | 13. The Lottery of Doom |

| XIV. Excalibur's Defeat | 14. A Deal With Disaster |

| To the Kintat | 15. They Too Can Fear |

| XVI. Five of the Kintat | 16. What Do You Want Of Us? |

| XVII. Man and Superman | 17. Destiny |

| XVIII. Conquest Beyond Space | 18. The Curtain Falls |

| XIX. Defy the Gods | 19. The Will to Live and Kill |

| XX. Experiment in Love | 20. Choice Between Death and Death |

| XXI. The Master Thief | 21. Experiment in Love |

| XXII. Through the Glass See Clearly | 22. The Death Cloud |

| XXIII. The Mother of All Living | 23. The Mother of All Living |

| XXIV. Million to One Chance | 24. The Magnificent Fools |

| XXV. The Room of the Matra | 25. To Die Alone |

| XXVI. The Sacrifice | 26. Vengeance |

| XXVII. The House On Cobblen Street | 27. Dust Unto Dust |

| None | 28. The Fork in Time's River |

HTML and EPUB versions the book edition of Seven Out of Time are available in Roy Glashan's Libary.

— Roy Glashan, 20 January 2020

Headpiece from "Argosy"

"YOU have not found Evelyn Rand."

Pierpont Alton Sturdevant did not raise his eyes from the papers he had been examining when I entered his office and his voice was dry as the rustle of wind in fallen leaves.

"No sir," I was forced to admit. "I've—" His hand gestured for silence.

The room was enormous, the desk massive, but the head of the law firm of Sturdevant, Hamlin, Hamlin and Sturdevant dominated both. This was not because of any physical quality. P.A. was quite average in stature. His hair, deftly arranged to conceal its sparseness, was gray, but it did not have the patches of white at the temples which fiction writers and movie make-up men like to believe are the invariable mark of position in business or the professions. The skin of his beardless face was netted with fine wrinkles, and tightly drawn over a skull almost femininely delicate.

In contrast to the near baldness of his scalp, shaggy brows shadowed Sturdevant's eyes. His nose was hawk-like. About the thin, tight line of his mouth there was a sort of sexless austerity.

Looking at him from the chair to which, with a terse "Good morning," he had motioned me, I had the notion that Sturdevant was very like some Roman emperor on the throne from which he ruled the world. My chief was cloaked in the same consciousness of undisputed power, of patrician aloofness from the common herd.

A very junior attorney in the august firm over which he presided, I might, to continue the fancy, have been some young centurion returned from Ulterior Gaul and hailed before his emperor to report on his mission. I had, in fact, just come back to the city from the remotest reaches of Westchester and what I had to report was—failure.

"If you continue the search, how soon do you think you will be able to locate her?"

"I don't know." I didn't like that if. I didn't like it at all. "I haven't been able to unearth a single clue as to what happened to her. The girl just walked out of her Park Avenue apartment house that Sunday morning and vanished. The doorman was the last person to see her. He offered to call a taxi for her and she told him that she would walk to church. He watched her go down the block and around the corner, and that was the last anyone ever saw of her."

"I could not take my eyes off the lass" the grizzled attendant had told me, "though the 'phone buzzer was goin' like mad. She swung along freelike an' springy, as if the ould sod was under her feet an' not this gray concrete that chokes th' good dirt. I was minded o' the way my Kathleen used to walk up Balmorey Lane to meet me after th' work was done, longer ago than I care to think."

By the way he spoke and the look in his eyes, I knew I needed only to tell him what it would mean to Evelyn Rand if word of the fact that she had never returned became known, to keep him silent.

And so it was with the elevator boy who had brought her down from her penthouse home and with the servants she had there: Frank Stone, the granite-visaged butter, buxom Mary Fox the cook, the maid, Renée Bernos, black-haired, roving-eyed and vivacious. Each of these would go to prison for life sooner than say a single word that would harm her, nor was this simply because she was generous with her wages and her tips. One cannot buy love.

"You are exactly where you was two weeks ago," Sturdevant murmured, "except for this." He turned the paper he'd been studying so that I could see it and tapped it with a long, bony forefinger.

IT was a statement of account, headed:

ESTATE OF DARIUS RAND in the

MATTER OF EVELYN RAND,

debtor to STURDEVANT, HAMLIN AND

STURDEVANT.

Beneath this heading was written a list of items,

thus:

1-27-47 ½ hr. P. A. Sturdevant, Esq. @$400 $ 200.00 1-27-47-2/10/47 88¼ hrs. Mr. John March @ $25 $2206.25 1-27-47 Disbursements and expenses to Mr. John March (acct. 2-10-47 attached) $ 64.37 Total $2470.62

"Two thousand four hundred seventy dollars and sixty-two cents"—Sturdevant's finger tapped the total—"up to last Saturday, and in addition there is the charge for this quarter hour of my time and yours, plus whatever you have spent over the weekend! Over two and a half thousand dollars, Mr. March," he repeated accusingly, "and no result."

He paused, giving me a chance to make excuses. But I wasn't having any. I bit my lip and waited for what I knew he was going to say next.

He said it. "As trustee of the estate of Darius Rand I cannot approve any further expenditure. You will return to your regular duties and I shall notify the police that Miss Rand has vanished."

That gave the signal to go ahead. "The hell you say!" I exclaimed, "You can't do that to her! You can't hand over her inheritance to charity." He wasn't the head of the firm to me then. He was a shriveled old curmudgeon for whom I didn't give a hoot in Hades. "You can't make that lovely girl who has always lived in a dreamland of her own, who has never been touched by the harsh realities of life, a penniless pauper. It would be murder, if not of a body, of a mind and a soul. You don't know what you're doing."

I stopped. I was out of breath, for one thing. For another, the calm cold way he was looking at me made me realize what a fool I was making of myself, getting all hot and bothered over the girl.

"I know exactly what I am doing," Sturdevant said when my silence gave him a chance to speak. "I know as well as you do that because of the embarrassment his actress wife caused him by trailing her escapades through the newspapers, Darius Rand in his will tied up his fortune in a trust fund. The income from it goes to his daughter Evelyn only as long as her name never appears, for any reason whatsoever, in the news columns of the public press.

"When she vanished, I determined, as chairman of her committee of guardians, to conceal the situation for a reasonable length of time, hoping that she would turn up or be found. That reasonable time has, to my opinion, expired. I can no longer justify my silence. Therefore, as trustee of—"

"The estate of Darius Rand," I broke in getting sore again. "You're measuring the happiness of someone against dollars and cents."

The faint shadow that drifted across Sturdevant's face might mean I'd gotten under his skin. But his answer didn't admit it. "No, Mr. March, I am measuring a sentimental attachment to someone over whose welfare I have watched for more than six years against the dictates of duty and conscience."

The old codger's weakening, I encouraged myself. "Aren't there times, sir, when one may forget duty and even conscience? Look here. Give me a week more. Just the week Itself. I'll take a leave of absence. I'll even resign, so you won't have to charge the estate for my time. I'll pay any necessary expenses out of my own pocket. All I want is for you to keep this thing away from the police and the papers for a week, and I'll find Evelyn before it's over, I'm as sure that I'll find her as that I'm standing here."

STURDEVANT'S eyebrows rose slightly. "You seem unduly

perturbed over the young lady," he mused, "for one who has never

seen her, for one who had never even heard of her fourteen days

ago. Or am I mistaken?"

"No. Fourteen days ago I was not aware that such a person as Evelyn Rand existed. But today," I leaned forward, my palms pushing down hard on the desk-top, "I think I know her better than I know my own sister. I know her emotional makeup, how she would react in any conceivable situation. That's what I've been doing ever since I found there were no physical clues to what has become of her. I have literally steeped myself in her personality. I have spent hours in her home, her library, her bedroom. I have talked, on one pretext or another, to everyone who served her, her hairdresser, her dressmaker, I know that her hair is the color of honey and how she wears it. I know that she is fond of light blues and pastel tones of pink and of leaf- green. I even know the perfume she has specially compounded for her."

In his little shop on Sixty-third Street, the walrus-

mustached old German in the long chemist's smock had looked long

at me, perturbation in his china-blue eyes. "Ich weiss

nicht," he muttered. "You say a friend from the Fräulein

Rand you are and a bottle from her individual perfume you want

to buy her for a present. Aber I don't know. Ven I say

so ein schönes Mädchen many lovers must have, she laughs

und says she has none. She says ven someone she finds who can

say to her so true t'ings about her soul as I say in de perfume I

make for her, then she will have found her sweetheart. But such a

one she has not yet found."

"Look," I argued. "Would I know the formula number if she did not tell it to me?"

I had got it from Renée Bernos, but the German was convinced. When I opened the little bottle that had cost me enough to have fed a slum family a month, my dreary hotel room was filled with the redolence of spring; of arbutus and crocuses and hyacinths and the evasive scent of leaf-buds, and with another fainter redolence I could not name but that seemed the very essence of dreams. For a moment it seemed almost as if Evelyn Rand were there with me....

"Ah," Sturdevant breathed. "And what did you hope to

accomplish by so strange a procedure?"

"I figured that if I could get inside her mind," I replied, "I should perhaps know what was in it when she walked down Park Avenue to Seventy-third Street, and turned the corner and never reached the church which she had set out for."

The arching of Sturdevant's shaggy brows was more pronounced this time. He was laughing at me, damn him, and he had every reason to.

"Yes?" he murmured. "Is that all you have done in two weeks?"

"This weekend I went out to Evelyn's country home, the house where she was born and where she spent her childhood. It was closed, of course, but I had obtained the keys from Miss Carter, your secretary. I spent most of Saturday in that house, and all of yesterday."

The other rooms had told me nothing about Evelyn

Rand. They were the commonplace living quarters of a wealthy

family, and that was all. But one dim and dusty chamber still

held the personality of the child Evelyn Rand. That was the

nursery.

I pulled out a bureau drawer too far, so that it fell to the floor and split, and that was how I found the thing. Only Evelyn Rand could know, if she were still alive and remembered, how long ago it had slipped between the side of that drawer end the edge of its warped bottom. At feast fourteen years ago, because, as I already had learned, when the girl was six and starting school the door of this room had been locked and never opened again.

As my fingers closed on the bit of carved stone that lay in a clutter of dolls' clothes, grimy picture books, battered blocks and mummified insects, something seemed to flow from it and into my blood, I was aware of a vague excitement and fear.

It was slightly smaller than a dime, approximately an eighth of an inch thick and roughly circular in outline, and there was, oddly enough, no dust upon it. It was black, a peculiar, glowing black that appeared to shimmer with a colorless iridescence. Almost it seemed as though I held in my palm a bit of black light strangely become solid. Too, it was incongruously heavy for its size, and when on impulse I tested it, I found it hard enough to scratch glass.

The latter circumstance made more remarkable the accomplishment of the artist who had fashioned the gem. For it was not a solid mass with a design etched seal-like upon it, but a filigree of ebony coils that rose to its surface and descended within its small compass and writhed again into view till the eye grew weary of following the windings.

On the window-sill to which I had taken the gem lay a magnifying glass. I wiped away the thick layer of dust that covered the lens and looked through it at the stone.

Now, sitting in the office with Sturdevant, I remembered

clearly the amazement I had felt when I studied that stone under

the glass.

Close-packed and intricate as were the thread-thin

loops, they formed a single continuous line. True, two or three

of the coils were interrupted at one point in the periphery by a

wedge-shaped gap about an eighth of an inch deep, but the rough

edges of the break made it obvious that this was the result of

some later accident and not a part of the original

intent.

Then I made another discovery: the coils were not smoothly polished as they appeared to the naked eye, but had traced upon them a myriad of microscopic scales, each perfect in outline and detail.

I could not bring myself to believe that any human could have had the skill and the infinite patience to have carved this out of a single piece of whatever the stone was. It must have been made in parts and cemented together. I bent closer, to see if I could find some seam, some evidence of jointure.

I saw none. But I saw the snake's head.

Tiny yet exquisitely fashioned, it lay midway between the gem's slightly convex surfaces, and at the hub of its perimeter, I could make out the lidless eyes, the nostrils, the muscles at the comers of the jaws, straining muscles because those jaws were widely distended.

To avoid any interruption of the design, the reptile had been graven as swallowing its own tail.

A strange toy for a little girl to have, I thought, and put it away in my vest pocket, meaning later to fathom out what it could tell me about Evelyn Rand.

"You seem to be making a good thing out of your

assignment." Pierpont Alton Sturdevant remarked. "Using it to

obtain a week-end in the country at the estate's expense."

I got pretty hot under the collar at that. It took an effort to remember that if I said what I wanted to, what faint chance there was of persuading him to permit me to continue investigating Evelyn's disappearance would be gone. At that, my voice had dropped a couple of notes in pitch when I went on.

"I also talked to the woman who was Evelyn Rand's nurse and her foster-mother after old Darius divorced his wife, the girl's constant companion till your committee sent her away to college."

"And what did you learn from Faith Corbett?" For the first time a faint hint of interest crept into Sturdevant's tone, though his face remained expressionless.

I hesitated. Could he possibly understand if I answered that question with complete honesty?

THERE was no sound in the office of Pierpont Alton Sturdevant except the almost inaudible burr of the electric clock on his desk. The long second hand of that clock could have swept hardly halfway around the dial before I made my decision.

"Nothing," I answered. "I learned nothing from her that I can put into words."

I had stopped at the door of the cottage and asked for

a drink of water. Faith Corbett, shrunken and fragile as a

withered leaf, had asked me in. Very willingly I accepted her

invitation to have tea with her; and soon the little old lady was

talking about Evelyn Rand.

"She was a dear child," the faded, tenuous voice mused as the scrubbed kitchen grew misty with winter's early dusk, "but sometimes she scared me. I would hear her prattling in the nursery and when I opened the door she would be quite alone, and no sign that anyone had been there. When I asked her who she'd been talking to she would look up at me with those great gray eyes of hers and gravely say a name, and it would be no name that I had ever heard.

"But it was something that happened the day before they took her away from me that upset me most of all," Faith Corbett said. "I didn't understand it and I will never forget it."

She took a nibble of her toast and a sip of her tea, but though I waited silently for her to go on, she did not. Her thoughts had wandered from what she had been saying, as old people's thoughts have a way of doing.

"What was it," I asked after awhile, "that happened the day before Evelyn went away to college?"

"I was packing her trunk," the old lady recommenced as if she had not paused at all. "I could not find her tennis shoes so I went downstairs to ask her what she had done with them. Evelyn was not in the house, but when I went out to the porch I saw her on the garden path. She was going toward the gate through the twilight, and there was an eagerness in the way she moved that was new to her. She walked as if she were going to meet a lover.

"I stood and watched, my heart fluttering in my breast for I knew there was no youngster about who had ever got so much as a second glance from my girl. She came to the gate and stopped there, taking hold of the pickets with her hands. Like a still white flame she was as she looked down the road.

"They had not put the macadam on it yet and the dust lay glimmering in the dimness. All of a sudden Evelyn got stiff-like and I looked to see who was coming."

The memory of that afternoon was still so vivid in my

mind that I could hear again the little gasp the old lady made as

she paused for an instant.

"The road was as empty and still as it had been

before," she told me slowly.

"The air was smoky, kind of, the way it gets in the fall and there wasn't a leaf stirring. But there must have been a breath of wind on the road because I saw a little whirl of dust come drifting along it. When it came to the gate where Evelyn stood it almost stopped. But it whispered away and all at once it was gone.

"All the eagerness seemed to go out of Evelyn. I heard her sob and I ran down the path calling her name. She turned. There were tears on her cheeks. 'Not yet,' she sobbed. 'Oh, Faith! It isn't time yet.'

"'It isn't time for what?' I asked her, but she would say nothing more and I knew it was no use to ask again...."

Faith Corbett's voice went on and on, telling me that she had rented this cottage with the pension the estate granted her and that it was hard to live alone. But I heard her with only half an ear. I was thinking of how in that smoky fall twilight long ago it had seemed to Faith Corbett that Evelyn Rand must be going through the garden to meet her lover. I was recalling how the grizzled old doorman had said, 'I was minded o' the way my Kathleen used to walk up Balmorey Lane to meet me;' and large in my mind was the oddly frightening thought that perhaps when Evelyn Rand had turned the corner into Seventy-third Street a whirl of dust might have come whispering across the asphalt....

"YOU learned nothing at all from Evelyn's old nurse?"

Pierpont Sturdevant demanded. "I cannot believe that."

"Well," I conceded, "she did make me certain that the girl was unhappy and lonely in that motherless home of hers. But, as an imaginative child will, she found ways of consoling herself."

"Such as?"

"Such as writing verse." I indicated the yellowed papers I had laid on Sturdevant's desk when I came in.

The only light left in the cottage kitchen had been

the wavering radiance of the coal fire in the range. So much

talking had tired Faith Corbett and she nodded in her chair, all

but asleep.

"Thank you for the tea," I said rising. "I'll be going along now."

The old woman came awake with a start. "Wait," she exclaimed. "Wait! I have something to give you. Something nobody but me has ever seen before." She rose too and went out of the room, the sound of her feet on the clean boards like the patter of a child's feet except that it was slower. I stood waiting and wondering, and in a little while she was back with a number of yellowed papers in her hand, pencilled writing pale and smudged upon them.

"Here," she said, giving them to me. "Maybe these will help you find her."

The papers rustled in my hand. I had been very careful to conceal from Faith Corbett the object of my visit, and I wondered how she could possibly know Evelyn Rand had vanished.

"Verse?" Sturdevant peered at the sheets dubiously.

Eager as I was to pierce the dry husk of rectitude that he wore, I had sense enough to retreat from my intention of reading to him, in that great room with its drape-smothered windows and its walls lined by drab lawbooks, the lines a child once penned in a sun-bright garden. He would hear the limping rhythm and the faulty rhymes, but he never would understand the wistful imagery of the words, the nostalgia for some vaguely apprehended Otherland where all was different, and being different must be happier.

"Poems," I assented. "They have told me more than anything else exactly what Evelyn Rand is like."

"And so it has cost the estate two and a half thousand dollars to find out that Evelyn Rand once wrote poems. You haven't even located a photograph of her, so that I can give the authorities more to go by than a bare description."

As far as anyone knew Evelyn never had been photographed. "I've done better than that," I said triumphantly. "I've found out that a portrait of her is in existence, painted by—" I named a very famous artist. For reasons that will shortly appear I shall omit that name from this account.

"Indeed." Sturdevant's brows lifted. "Why did you not bring that here instead of this trash?" He flicked a contemptuous finger at the sheaf of old papers.

"Because it is in a gallery on Madison Avenue. I intend to go there as soon as you finish with me, and—"

His look checked me. "You seem to forget, Mr. March, that I have canceled your assignment to this matter."

There it was! I hadn't changed his decision in the least. "You—!"

I didn't get any further than that because the annunciator on his desk interrupted me with its metallic distortion of human speech. "Nine-thirty, Mr. Sturdevant," it said. "Mr. Holland of United States Steel is here for his appointment."

Sturdevant clicked up the switch key that transformed the device from a receiver to a transmitter. "Send him in, Miss Carter. And make a note of this, please. John March has been granted a leave of absence, without pay, for one week from date. This office will do nothing in the matter of Evelyn Rand until Monday the twenty-first."

He turned to me and I swear there was a twinkle in his eyes. "Remember," he said. "Time is of the essence of the contract."

I was to recall that warning, but in a sense far different than he intended.

ART lovers are not as a rule early risers, and so after I had purchased a catalogue from the drowsy attendant in the foyer and passed through the red-plush portières before which he sat, I had the high-ceiled exhibition room to myself.

Shaded, tubular lights washing the surfaces of the paintings on the walls accentuated the dimness that filled the reaches of the gallery. A decorous hush brooded there, the thick, soft carpeting muffling the sound of my feet, close-drawn window drapes smothering traffic noise from without. The atmosphere was thick and oppressive.

I passed a circular seat in the center of the floor and saw Evelyn Rand looking at me from the further wall.

I knew her at once, although I had never seen her pictured anywhere. So sure was I that this was the portrait I had come to seek that I did not look at the gray pamphlet I held but went right to it.

I was conscious only of her face at first, ethereal and somehow luminous against the dark amorphous background of the painting. It seemed to me that there was a message for me in the gray, frank eyes that met mine, a message somewhere beneath their surface. It seemed to me that the satin-soft red lips were on the point of speaking.

Those lips were touched with a wistful smile, and there was something sad about them. Somehow the painter had contrived to make very real the glow of youth in the cheeks and in the honeyed texture of the hair; but there was, too, something ageless about that face, and a yearning that woke a response within me.

Yes, this girl could have written the poems that were locked now in a drawer of my desk. Yes, she would be loved by everyone who had the good fortune to know her.

She must have been about sixteen at the time of the portrait. The body within the soft blue frock—a misty blue, like the sky when it is brushed across with cloud—was just budding into womanhood. The hollows at the base of the neck were not yet quite filled.

A fine gold chain circled that neck. Pendant from it was a black gem, round and a little smaller than a dime. I recognized it. It was a replica of the one I had found in the nursery. There had been two of the things then—

My forehead wrinkled. At the edge of the amulet there appeared a wedge-shaped break about an eighth of an inch deep.

That was odd. The pictured Evelyn Rand was, as I have said, certainly sixteen. I might be mistaken by a year, not more. When she had sat for that portrait the gem was lost, and locked behind a door that had not been opened for almost ten years. This must be another. I was mistaken in thinking that the break was at exactly the same point, shaped exactly the same.

There was one way of finding out. The carved black stone was in my vest-pocket. All I had to do was take it out and compare it with the one in the picture.

I fished the curious gem out of my vest-pocket and looked from it to the painting and back again. The pictured pendant and the stone in my fingers were the same. No accident could possibly have marred two different objects, no matter how similar, in precisely the same way.

Somewhere outside, a tower clock started chiming, the strokes coming dully into the room. Automatically I turned my wrist to check my watch. It was ten, right on the dot.

"An interesting bit." a low voice said. "Well worth the study you are giving to it."

I had thought myself alone in the gallery, yet now the voice did not startle me. I did, however, return the black stone to my pocket and button my coat over it as I agreed, "Yes. Very much so."

THE man was short, so short that the top of his head was

at the level of my shoulder, and the first thing I noticed about

him was that he was completely bald. The head seemed out of

proportion, too large for the body it topped.

"Of course you have noticed," he went on, "how painstakingly every physical detail has been brought out. One has the impression that merely by reaching out one might feel the warmth of the girl's flesh, or straighten the fold in her frock a puff of wind has disarranged, or take that black pendant in one's fingers and examine it more closely."

Light reflected from the portrait of Evelyn Rand fell on the little man's face but left the rest of him obscure, so that his odd countenance seemed to hang disembodied in the gloom. It was round, no feature prominent enough to claim notice, but I did observe that brows and lashes were either absent or so light as to be imperceptible against the yellowish skin. The latter was of an odd lusterless texture, yet so smooth that I had a disquieting sense that it was artificial.

There was nothing artificial, however, about the tiny eyes; black eyes keener, more piercing, than any I had ever seen.

Their owner seemed unaware of my scrutiny. He was peering at the painting and his low, clear voice flowed on musingly, as though he were speaking his thoughts aloud, only half aware of my presence.

"How much of his subject's personality the artist has contrived to convey! She is not quite in tune with the world where she finds herself. All her life she has been lonely, because she does not quite belong. She has a sort of half- knowledge of matters hidden from others of her race and time, not altogether realized but sufficiently so that dimly she is aware of the peril which the full unveiling of that knowledge would bring upon her."

I studied the portrait. I couldn't see all that in it.

"She has learned now," the little man murmured, "what she only vaguely guessed at when that picture was painted."

That turned me to him. "What makes you say that?" I demanded, reaching to take hold of his upper arm.

I felt the roughness of fabric, the hardness of flesh beneath; then—though I was not conscious of any movement on his part—my fingers were closing on empty air and the fellow was standing beside me precisely as he had been, his speech a quiet, drowsy murmur.

"You know her." It was not a question but a statement. "You know how well the artist has done his work." Oddly enough, we both ignored the curious incident as one would a paradox in a dream.

"I know what she is," I replied. There was something puzzling here. "Though I have never met her, never spoken to her." Had something more than interest in a work of art brought this strange individual here? "What is the peril that threatens her?" I asked, to lead him on.

I expected either a plea of ignorance or an answer that would tie the little man to the vanishing of Evelyn Rand. I did not expect what he said.

"The artist sensed it. He put it on the canvas for us to see."

I looked back at the portrait. There was the girl's figure on it. There was the dark and formless background. There was nothing else.

"I'm sorry," I said. "I don't know what you mean."

"Look." I felt fingers brush across my eyes. He must have reached up and touched them, but I did not, as ordinarily I should have, resent the liberty. I forgot it as soon as it occurred.

For behind the figure of Evelyn Rand there was no longer formless shadow. I saw, instead, a desolate landscape informed with some quality, some eerie strangeness, that made me aware at once that it existed somewhere, but not on this planet. It inspired me with something of awe, that quality, and something of an inexplicable dread.

No living thing was visible to arouse that sense of apprehension. It seemed to come from the very pattern of the scene itself; from the sky that was too low and of a color no sky should have, and most of all from a monstrous monument that loomed against the close horizon. Black this enormous figure was, the same strangely living black as the stone in my vest pocket, and grotesquely shaped. There spread from it an adumbration of infinite threat of which Evelyn was as yet unaware—

I twisted around to the little man. "Where is that place?" I demanded. "Tell me where it is!"

"Not yet." The fellow peered at me with the detached interest of an entomologist observing an insect specimen, and somehow my momentary excitement cooled. "Not yet," he repeated. I became aware of how absurd was my thought that Evelyn was in some nameless danger from which only I could save her. "When it is time you will come to me. Here." He thrust a white oblong into my hand. I glanced down at the card.

There was not enough light to read it. I lifted it to catch the reflection from the portrait—and realized that the little man was no longer beside me.

He was nowhere in the room. I shrugged. He must have gone swiftly out, the carpeting making his footfalls soundless. Bon-n-ng. The tower clock was striking again. Bong. It was striking not the half-hour but the hour. It didn't seem that we had talked so long. Instinctively, I looked at my wrist watch.

It was ten o'clock. The watch hadn't stopped. The second hand was whirling merrily around its tiny circle, and the two longer hands insisted that the time was still ten o'clock.

They hadn't moved in all the time the little man had been speaking to me!

FOR a long minute the shadows of that hushed art gallery

hid the Lord alone knew what shapes of dread. The painted faces

leered at me from the walls—

All but one. The face of Evelyn Rand, its wistful smile unchanged, its gray eyes cool and frank and friendly, brought me back to reason. Her face, and the fact that behind her I could see no strange, unearthly landscape but a formless swirl of dark pigment, warm in tone and texture and altogether without meaning except to set off her slim and graceful shape.

I was still uneasy, but not because of any supernatural occurrence. A fellow who's never known a sick day in his life can be forgiven for being upset when he finds out there are limits to his endurance.

For two weeks I had been plugging away at my hunt for Evelyn Rand, and I hadn't been getting much sleep, worrying about her. I hadn't had any at all last night, returning from Westchester in a smoke-filled day-coach. I was just plain fagged out, and I'd had a waking dream between two strokes of the clock.

Dreams, I knew from the psychology course I once took to earn an easy three credits, can pass through one's mind in virtually no time. That I should have imagined Evelyn in some strange land, with some obscure menace overhanging her, only symbolized the mystery of her whereabouts and my fears for her. The little man represented my own personality, voicing my inchoate dreads and tantalizing me with the promise of a solution to the riddle, deferred to some indefinite future. "Not yet," he had said.

It was all simple and explicable enough, but it was disturbing that I should have undergone the experience. Maybe I ought to see a doctor. I bad a card somewhere.

A card—there was one in my hand! Fear returned to me swiftly. The card in my hand was the one I had dreamed that the little man had given me. And it was real! Objects in dreams do not remain real when one awakes....

But there was a rational explanation for this too. The card hadn't come out of the dream It had been in the dream because I already had the card in my hand. It must have been in the catalogue. Leafing the pamphlet as I was absorbed in contemplation of Evelyn's portrait, I had abstractedly taken it out, unaware that I was doing so.

I looked at it, expecting it to be the ad of some other gallery connected with this one, of some art school or teacher. But all the card bore was a name and an address:

Achronos Astaris

419 Cobbles Street,

Brooklyn

I think it was the "Brooklyn" that finally banished my renewed uneasiness. There is something solid and utterly matter-of-fact about that Borough of Homes, something stodgy and unimaginative and comfortable about its very name. I stuffed the card among a number of others in my wallet and forgot about it.

I took a last, long look at the portrait of Evelyn Rand. My reconstruction of her personality was complete. All that was left was to find her.

All that was left! I laughed at myself as I turned to leave the exhibition room. I had hoped somehow, somewhere among the things she had touched, the people she had known, the scenes through which she had moved, to come upon a hint of where and how to look for her. I had found nothing. Worse, every new fact about her that had came to fight denied any rational explanation of her disappearance.

THERE was no man in whom she was enough interested to

make the idea of an elopement even remotely possible. Apparently

she had been content with her way of life—quiet, luxurious,

interfered with not at all by the trustees of the estate. To

conceive the sensitive, shy girl as stage-struck would be the

height of absurdity.

No reason for her vanishing of her own will would fit into Evelyn's personalty as I knew it now.

The possibility of foul play was completely eliminated. Kidnappers would have made their demand for ransom by this time. Seventy-third Street had been crowded with church-goers that Sunday morning; no hit-and-run accident, with the driver carrying off his victim, could have occurred unobserved. The police and hospital records had offered no suggestion of any more ordinary casualty that might have involved her. The charities to receive the income from the estate had not yet been decided on, so that motivation—far-fetched anyway—was out. Finally, Evelyn Rand was the last person on earth to have an enemy, secret or otherwise.

The more I had learned about the girl, the less explicable her absence had become. Except for one thing—the whispering swirl of dust.

Angrily I told myself that it was absurd to attach any importance to that detail. In Faith Corbett's dim kitchen, with the old crone mumbling over her toast and tea, the ides had seemed almost reasonable. In the brittle winter sunshine that flooded Madison Avenue, with the roar of New York's traffic in my ears and the bustling throngs jostling me, I knew how fantastic it was.

I was licked. The best thing for me to do was to go back to the office and tell old Sturdevant to call in the police.

I'd be damned if I would! I'd fought like mad to get a week's grace for myself, and I would use that week. Something would turn up. Something must—

I stopped thinking. I stood stock-still, my heart hammering my ribs, and pulled another breath into my lungs. It was there, faint but unmistakable. The mingled scent of arbutus and crocuses and hyacinths, and the nameless redolence of dreams. The fragrance of spring—the perfume that was used by Evelyn Rand, and Evelyn Rand alone.

She was near—very near. She had passed this way minutes, seconds before, for the delicate scent could not have lived longer in the gasoline fumes and the reek of the city street.

I looked around. I saw a messenger boy lounging along, businessmen bustling briskly past, a rotund beldame in mink descending from a sleek limousine, someone's bright-eyed, chic stenographer on her way to the bank on the corner with a deposit book held tightly in her gloved little hand. A shabby-coated old man was poring over a tome at a second-hand bookstore's stall beside me. I was in the middle of the block and nowhere in its length was there anyone who possibly could be Evelyn Rand, even in disguise.

I must admit that I was considerably shaken. That dream I'd had in the art gallery hadn't helped my nerves, and now this whiff of Evelyn's perfume—I grinned lopsidedly. I was rapidly turning into a screwball. First I saw and heard things that didn't exist, and now I was taking to smelling things.

"You'd better start pulling yourself together," I muttered and turned to the book-stall to give myself an excuse for standing still and thinking things over. I picked up a volume at random. The blistered, water-soaked cover almost came away in my hands as I opened it. The paper of the title page was mildewed, powdery. I read the name of the book, casually at first—then with a shock of surprise. It was The Vanished.

Under the Old English type of the title there was a short paragraph in italics:

Here are the tales of a scant few of those who from the earliest dawn of history have vanished quietly from among the living yet are not numbered among the dead. Like so many whispering whorls of dust they went out of space and out of time, to what Otherwhere no one still among us knows, and none will ever know.

"Like so many whispering whorls of dust." Was that pure coincidence?

I TURNED the page and read the list of chapter headings:

Elijah; Prophet in Israel. Arthur of Camelot. Tsar Alexander the

First. John Orth; Archduke of Tuscany. François Villon; Thief.

Lover and Poet. The Lost Dauphin. Those Who Sailed on the

Marie Celeste. Ambrose Bierce Joins the Phantoms of his

Pen. Judge Crater of New York. And, How Many Unrecorded

Others?

That "How Many Unrecorded Others" gave me an idea. Not a reasonable one, I'll admit, but no less logical than the rest of what I'd been doing to find Evelyn Rand. The idea was that perhaps somewhere in this book I might find that hint, that suggestion of what might have happened to her, for which I'd been looking.

I shrugged. It wouldn't hurt to read the thing.

I went into the store, shadowed, musty with the peculiar aroma of old paper and rotted leather and dried glue found only in such establishments. A gray man in a long gray smock shuffled out of the dusk between high shelf-stacks.

"How much is this?" I inquired, holding the volume up. "I want it."

"Hey?" He peered at me with bleared, half-blind eyes. "Hey?"

"I want to buy this book," I repeated. "How much do you ask for it?"

"This?" He took it in his claw-like hands, brought it so close to his face I thought he would bruise his nose. "The Vanished? Hm-m-m." He pondered the matter of price. Finally he came out with it. "Thirty-five cents."

"Little enough." I shoved my hand in my pocket, discovered I had no small change. "But you'll have to break a five for me," I said, taking my wallet from my breast-pocket. "That's the smallest I have."

"You're a lucky man," the bookseller squeaked. "To have five dollars these days." His shrill, twittering laugh irritated me. I jerked the bill from the fold so hard that it brought out with it a card which fluttered to the floor.

The gray man took the greenback and shuffled off into the misty recesses beyond the shelving. I bent to retrieve the white card.

I didn't pick it up. I remained stooped, my fingers just touching it, my nostrils flaring once more to the scent of spring, the perfume of Evelyn Rand.

The sense of her presence was overpowering, but I knew, this time, that she was not near. The perfume came from that card on the floor, and the printed name on it was Achronos Astaris.

At last I knew where to look for Evelyn Rand.

"HEY, here's your change." I straightened, thrusting the card into the side-pocket of my coat. "Keep it," I told the gray man, grinning. "And keep the book too. I don't need it any more." I laughed out loud as I strode out of that musty store.

My exuberance didn't last long. The thing that dampened it was my sudden realization that I didn't know where Cobblen Street was, had no idea of how to get there. I was born on West Eighty- third Street and have lived in New York all my life, but Brooklyn is an unknown world to me as it is to most other Manhattanites. I always get lost when I cross the river.

I hate to ask directions. It seems to be a confession of incompetence. But I had to if I wanted to get out to 419 Cobblen Street. So when I caught sight of a policeman standing on the corner, I approached him with my question.

"Cobblen Street," he growled. "Never heard of it."

"It's in Brooklyn," I suggested.

"Oh! Brooklyn." Then we went through a procedure that seemed to me interminable. The cop got out his little red book and, after some stumbling, finally discovered Cobblen Street. Several moments later he located the number and read aloud a complicated series of directions involving the El, the subway and eventually a ferry. I clung to the subway instructions, a little dazed.

"Does that mean the station is four blocks west of Cobblen Street," I asked, "or that I walk four blocks west from the station?"

He took off his cap and scratched his head. Then he got a sudden inspiration. "Wait! I'll look in the front of the book."

I stopped him hurriedly. "Thanks for your trouble, but if it's as complicated as all that I'd better take a taxi."

I hailed one, gave the driver the address and climbed in. For the first time that day I felt like smoking. I got my pipe out, tamped its bowl with the mixture that after much experimentation I've found suits me exactly, puffed flame into it.

The bit was comfortable between my teeth, and the smoke was soothing. I became aware of how very tired I was. I moved over into a corner and leaned back, stretching my legs diagonally. I am well over average height and am invariably cramped in any kind of vehicle.

The change in my position brought my face into the rear-view mirror. There are two things that irk me about that physiognomy of mine. It is unconscionably young-looking in spite of the staid and serious mien I assume when I can remember to do so. I'm sure Miss Carter, or "Persimmon Puss" as the irreverent office boys refer to P.A. Sturdevant's secretary, considers my youthful appearance ill-suited to the dignity of Sturdevant, Hamlin, Hamlin and Sturdevant. Then too, my nose is slightly thickened, midway of the bridge, and there is a semicircular scar on my left cheek, mementoes of encounters with football cleats in my unregenerate days.

Otherwise my appearance is not really revolting. I have a thick shock of hair, a rather ruddy brown in color, eyes that almost match it in hue, and a squarish jaw which I like to think is strong and determined. I'll never take any beauty contests, but neither do I generally frighten people in the street.

We were on Fourth Avenue now for a few blocks, and then on Lafayette Street. Tombs Prison lifted its dingy bulk to my left, was succeeded by the white granite of the monumental structures surrounding Foley Square. The Municipal Building straddled Chambers Street like a modern Colossus of Rhodes and then the blare and hurly-burly of City Hall Park was raucous in my ears.

A truck-driver disputed the right of way with my cabby. "Where the hell do yeh t'ink yer goin?" he wanted to know.

Where did I think I was going? Why did I think I was going toward Evelyn Rand, when all the evidence I had of any connection between her and this Achronos Astaris was the faint hint of her perfume on his card? The card might never even have been near Cobblen Street. Hundreds of them must have been inserted between the leaves of the art gallery's catalogues, and that probably had been done at the printers. If the scent did cling only to this single one, it still might have been touched by her at some place Astaris never had even heard of.

Pessimism, a conviction that I was on a fool's errand, replaced the buoyant confidence with which I'd started out. That scent of spring and dreams had made me so sure that I was on the track at last; maybe it would restore my confidence.

I fished out the card, lifted it to my nostrils. All I smelled was paper and ink.

THE fragrance had not, then, come from this bit of pasteboard.

But it had been there, without question, in the street outside

that bookstore and inside it....

I had made a fool of myself. Just before I entered it, Evelyn had been in that store! I had missed her by seconds. I was running away from her, not toward her.

I grabbed the sill of the narrow window before me. "Turn around!" I ordered. "Turn around and go back to where we came from!"

"Nix, fella," the cabby grunted. "It's ten days suspension or my license if I turn here on th' bridge."

He was right. We were on the bridge and the traffic regulation is rigidly enforced there. We would have to go on to the Plaza at the Brooklyn end, and then return.

"All right," I said.

That was the longest, most chafing mile I have ever ridden. The noon rush was beginning and the roadway was jammed. But finally the taxi circled the curve of the open space where the bridge ends, and slowed. "Well," the hackman grunted to his windshield. "You change your mind again, or is it go back?"

I opened my mouth to tell him, "Back, of course," but the words died on my lips. He'd jerked around, his swarthy face startled.

"Boy!" he exclaimed. "The way you said 'Go on!' I t'ought you'd picked up a dame!" He turned again and the cab wheeled out of the Plaza, running down a narrow street in the direction of a traffic arrow that had painted on it, To Borough Halt.

The taxi's sudden burst of speed threw me back against the leather seat. I stayed like that, my teeth biting into the bit of my pipe.

Who was it that had spoken to the taxi-driver, telling him to go on to Cobblen Street?

Abruptly I chuckled. I had recalled a similar experience told me by a friend, and I had the answer. Some woman in a car passing alongside of my cab had said "Go on," to her own driver. Just the right cant of the other auto's windshield, perhaps aided by a puff of breeze, had carried her voice to my hackman's ear. Listening for a reply to his query, he had thought the words had come from within his own vehicle.

The explanation was simple and plausible and it satisfied me. It was with no sense of yielding to some guidance outside my own will that I decided to continue on and interview the oddly-named Achronos Astaris. I still clung, rather hopelessly, to my first notion that he might have something to do with Evelyn Rand, and so much time had now elapsed that an hour's more delay in returning to the Madison Avenue bookstore would make no difference.

Just as I came to this conclusion there was a mild fft from somewhere beneath me and a violent verbal explosion from the cabby. He veered the car to the curb and braked it, still luridly sounding off.

He ran out of breath at last, and subsided from oral eruption to more purposeful action, the first step of which was to reach over and snap up his flag.

"I got a flat, buddy," he informed me, quite unnecessarily, as he heaved out of his seat. "Take me five-six minutes to fix. That's Borough Hall ahead there. Mebbe if you'd ask a couple guys where this Cobblen Street is while I'm workin' it'll save time."

"I've got a better idea," I said. "I'll pay you off now and walk the rest of the way. According to the cop's book it's only four blocks from here." I paid him his fare and alighted.

ASKING questions was one thing, getting informative replies

another. In turn a news-stand attendant, a brother attorney

hurrying, briefcase in hand, toward the nearby courthouse, and a

bearded derelict standing hopefully beside a little portable

shine-box, shrugged doubtful shoulders and looked blank. Finally,

I approached a policeman with some trepidation. If he produced a

little red booklet— But he didn't. "Cobblen Street," he

said. "That's over on the edge of Brooklyn Heights. Cross this

here street and go past that there corner cigar-store and keep

going and you'll walk right into it."

I heaved a sigh of relief—but relief was premature. My brisk pace slowed as I found myself in a maze of narrow, decorous streets labeled with such curious names as Orange, Cranberry, Pineapple. I entered a still narrower one called College Place and brought up facing a blank wall that forbade further progress. I extricated myself from that cul-de-sac, walked a little further and halted.

I had lost all sense of direction.

From not far off came the growl of city traffic, the honk of horns, the busy hum of urban life, but all of it seemed oddly alien to this street of low, gray-façaded houses with high stone stoops and windows shuttered against prying eyes. Years and the weather had spread over them a dark patina of age, yet there was about them a timeless quality, an aloofness from the flow of events, from the small affairs of the men and women whom they sheltered. The houses seemed to possess the street, so utterly that no one moved along the narrow sidewalks or appeared at the blinded windows, or let his voice be heard.

I was strangely alone in the heart of the city, strangely cloistered in drowsy quiet.

Into that quiet there came a low sonorous hoot, swelling till the air was vibrant with it, then fading away. The sound came again, and I knew what it was. A steamboat whistle. I recalled that we had not come far from the Bridge, that the East River must be very near. And I recalled, too, that the policeman had said that Cobblen Street was on the edge of Brooklyn Heights. It would overlook the river, then, and that whistle should give me the direction.

Then I spotted a drugstore on the corner, and headed for it. I'd get straightened out there.

The shop was small, low-ceiled, the shelving and showcases painted white and very clean. There was no soda fountain. Glass vases filled with colored water, red and green, stood at either end of a high, mirrored partition.

From behind this came the clink of a pestle in a Wedgwood mortar. The sound continued when I cleared my throat, loudly, but a tall, stooped man in a white coat came out through a curtained doorway, tugging at one drooping wing of a pair of walrus mustaches. He blinked genially at me through thick, silver-framed eyeglasses.

"Warm isn't it?"

"Very warm." I agreed, fumbling in my pocket for Astaris' card. "I hate to disturb you just to ask directions, but I've been wandering around this Brooklyn of yours till I'm nearly crazy. I'm looking for Cobblen Street. Four—" I read the number printed on the pasteboard. "Four-nineteen."

The druggist followed the direction of my gaze, and then he looked into my face, the smile gone from his. "Plum Street"—he gestured to his entrance— "runs into Cobblen, but"—he paused uncertainly—"but are you sure you want that number?"

"Of course," I answered, a bit puzzled by the change in his manner. "It's right here, on this card." I held it out to him.

He made no move to take it, or even to look at it. "Listen, old man." His hand was on my arm, solicitously. "Cobblen Street is very long and there might be an easier way for you to get to where you want to go than along Plum. Sit down here a minute," he led me to a bentwood chair in front of a showcase, "while I go in back and look up just where four-nineteen is."

I couldn't quite make him out, but he was being so decent to me that I couldn't argue with him. I sat down and watched him hurry back behind the partition to consult, as I supposed, another one of those little red guidebooks.

I was mistaken. I have exceptionally keen hearing and so I caught from behind that mirrored wall, something which I definitely wasn't supposed to hear. The pharmacist's whisper, suddenly excited: "Tom! Grab that 'phone and dial Dr. Pierce. I think that fellow out there is the patient that got away from his asylum last night."

Another whisper came back: "How do you figure that?"

"He just asked me for four-nineteen Cobblen. Four-nineteen, mind you. And he showed me what he said was a card with that number on it. But there wasn't any card in his hand. There was nothing in it at all."

"Maybe he is that nut," I heard the other whisper respond. "You go back out there and keep him talking and I'll get Pierce's keepers over here. Here, you'd better take this gun along in case he gets violent."

That got me up out of the chair and out of that store in a rush. I was a block away before I slowed and stopped.

NO card, huh, I thought. It was the druggist who was crazy,

and not I. The card was still in my hand. I could see it, feel

it, read the name and address on it. I had found it in the

catalogue of the exhibit.

Then I realized that I didn't know I'd found it there. I'd decided that the card had been between the pages of that pamphlet because otherwise I would have had to believe that it had been handed to me during a space of time that occupied no time at all, by a man who did not exist. But if the card itself did not exist? Here it was between my thumb and fingers, white, crisp, unquestionable. Even if the mustached pharmacist hadn't seen it, others had. The gray bookseller. The policeman on Madison Avenue.

Had they? I had dropped it in the bookstore, had bent to pick it up, but the near-sighted dealer had said and done nothing to indicate that he was aware of what I reached for. Nor, I now recalled, had I shown it to the cop.

What if I had not? The card was real, couldn't be anything else but real. I had been meant to hear the druggist's whisper, saying that it was not. It was his perverted idea of a joke. The best thing to do about the incident was to forget it.

A sign projecting from a street-lamp told me I was on Plum Street. The sound of a steamboat whistle gave me the direction of the river. I got moving again.

This street was as deserted as those through which I had come. Yet I had an uneasy feeling that I was not alone in it, that someone was keeping ahead of me, just ahead, although I could see no one. Once I caught a flutter of blue, of a misty blue like the sky when it is brushed across with cloud. It was as if I had glimpsed something out of the corner of my eye, except that it was not to one side but before me.

The long block started to slope upward, curving. I went around the curve and ahead of me a vista opened.

The sidewalk climbed quite steeply to its end, about a hundred yards farther. Beyond was brightness, the brightness of the sky over water and, apparently suspended in that brightness, there was a white and gleaming mass, breathtakingly beautiful.

Stone and steel and glass, the gargantuan towers were gathered into a giants' city to which one must climb on some incredible bean-stalk. Each separate structure was distinct, yet all merged together in a jagged pyramid that soared high and ever higher till its topmost pinnacle seemed about to impale the sun.

Manhattan's skyscrapers these were, challenging the heavens.

After a while my gaze drifted downward to the base of that enormous pyramid, to the swirling, cloud-like haze that had obscured the foundations of the skyscrapers and made them seem to hang unsupported in mid-air. Odd, I was thinking, that so late in the day the mists should be still heavy on the Bay. But the obscurity was neither cloud nor mist, and it did not lie over the confluence of the Hudson and the East River. It was on the nearer shore.

What I had thought to be cloud was a low building toward which Plum Street ascended and against which it ended, a low, gable- roofed wooden house with a little green lawn in front of it. A gravel path went through the lawn to an oaken door that made a dark rectangle in the white, clapboard façade.

I halted at the end of the sidewalk. It came to the forefront of my mind that while my eyes had been lifted to the skyscrapers they had vaguely caught movement there ahead. Someone had gone up that path and through that door. That someone must be the same evanescent individual who had gone up Plum Street just ahead of me. Too bad, I thought, that I had just missed seeing her.

It did not seem strange, then, that I should be so sure there had been someone ahead of me, though I had seen or heard nothing substantial to tell me so.

It seemed no stranger than the presence of the gabled frame house here in the heart of New York. One comes upon just such relics of more gracious days in the most unlikely parts of Gotham. Mostly they are dilapidated, ramshackle, mouldering to ruins. This one, while it had a flavor of antiquity about it, was perfectly preserved—the pickets of the wrought-iron fence around its little lawn erect and unscarred by rust, its windows washed and gleaming, though darkened by blinds pulled down behind their panes.

From the center of the long roof a small, domed cupola rose. Around this ran a narrow, railed balcony.

Something of my school-days' history returned to me. I wondered if George Washington had not perhaps stood on that balcony, spyglass to eye, watching General Gates' redcoats filing into the row-boats that would bring them across the River for the Battle of Brooklyn Heights. Perhaps this building had been his headquarters during that momentous encounter. That would explain its preservation.

On either side of it was a four-storied, graystone house, each the beginning of a long row of similar ones. In front of the house on my left stood a tall lamp standard bearing a street sign, white letters on a blue background. I could read those letters from where I stood.

They formed the words, Cobblen Street.

On the third step of the high stoop behind that lamp-post was painted a number—415. I looked at the stoop of the stone house to the right of the wooden one and read, 423. I looked to make sure.

The low house, with its little lawn and its balconied cupola, was 419 Cobblen Street!

AS I went across to the house some errant breeze lifted a whirl of dust from the asphalt. It accompanied me across the opposite sidewalk and through the gate in the tall fence of hand-wrought iron. It whispered about me as I went up the path, and though I felt the gravel underfoot there was no sound in the hush except the soft hiss of the tiny, impalpable maelstrom.

The high portal, darkened by the years to the tone of old leather, opened smoothly, silently before me. Quite without hesitation, almost as though I were no longer master of my own movements. I stepped through the aperture into cool dimness.

The door thudded dully behind me. It shut out the city's low murmur, so familiar that I had not been aware of it till now it was gone. It was as if a barrier had come between me and the world I knew.

Passing from the bright winter sunshine to this semi-darkness, I was temporarily blinded. I halted, a bit bemused, waiting for sight to be restored.

I could make out no detail of the place. I could see only a gray, featureless blur. But I had an impression of spaciousness—of space itself. Of a vast, limitless space that could not possibly be confined within the four walls of a house, or within the four points of the compass.

Abruptly my thigh muscles were quivering and the nausea of vertigo was twisting within me. I seemed to be on the brink of a bottomless chasm. If I took another step I would hurtle down, forever down. The impulse seized me to take that step, to throw myself, plummeting, into that abyss—

Hold it! I told myself, voicelessly. Get a grip on yourself. This is only the hall of an old house. In a moment your pupils will adjust themselves and you will see it—walls papered with the weeping-willow design you've always liked, hooked rugs on a floor of adze-hewn planks, perhaps a graceful balustraded staircase....

Subconsciously I must already have been aware of all this, for the very foyer I described took shape now out of the formless blur. The design I remembered from the Early American exhibit of the Metropolitan Museum patterned the faded walls. Wide planks formed the floor, rutted with decades of treading feet and keyed together by tiny double wedges of wood, their dull sheen brightened by oval rugs whose colors were still glowing despite the years since patient hands had fashioned them. Directly ahead of me the wide staircase rose gently curving to obscurity above, its dark rails tenuous and graceful.

"Well," I said, turning to the person who had admitted me. "This is—" I never finished the sentence.

No one was there—no one at all.

Someone had opened the door for me, and no one had passed me, going away from it. But of course—whoever it was had slipped out as I entered. Was Brooklyn inhabited exclusively by practical jokers? This one wasn't going to get away with it. He couldn't have gone far. I grabbed the doorknob, determined to go after him.

The door didn't open. It was locked; I was locked in! That was going too far, much too far. I—

A silken rustle behind me twisted me around. I started to speak—my mouth remained open, the angry words dying unspoken.

DOWN the stairs from above were coming tiny feet, a froth of

lace that could only be the hems of the multitudinous petticoats

which women wore in the days when this house was built. The filmy

blue of a wide hoopskirt descended into view, a pointed bodice

tight on a waist that my one hand could span.

I shook my head, trying to shake the cobwebs out of it. What the devil was this?

The crinolined maiden paused on the stairs, a slim white hand to her startled bosom. For a moment the shadow of the ceiling was across her face, and then I saw it, somehow luminous against the dark background of the stairs.

It was the face of Evelyn Rand. The soft red mouth was tight with pain, the gray eyes peering down at me haunted with a strange dread; but it was the face that had looked out from the portrait on Madison Avenue.

"Evelyn!" I cried, leaping forward. My feet struck the bottom step, pounding upward—and were suddenly motionless.

She wasn't there any longer. She wasn't above me on the stairs. She hadn't retreated, startled by my cry. She had blinked out, in the instant it had taken me to get across the floor and three steps up. But something was left of her. A faint sweetness on the air—the scent of spring, the scent of dreams.

Of dreams. Had I only dreamed that I saw her?

"Not quite," a low, toneless voice said behind me. "She was not there, but neither did you dream that she was."

I wheeled, my breath caught in my throat.

Just below me, a shaft of vagrant light gleaming on the polished scalp of his too-large head, his lashless, disquieting eyes pinpoints of flame in the gloom, was the little man of the art gallery.

But that could not be. He was a figment of my imagination, an illusion that had appeared and vanished between two strokes of a clock. My fingers dug into the rail they had grasped to aid me up the stairs. That at least was firm and hard. That at least was real.

"Less real than I," said the little man who twice had apparently materialized out of nothingness. "That staircase exists only in accord with your concept of it, as do the walls about us and the floor on which we stand."

I had not spoken aloud the thought to which he thus responded. Was he reading my mind?

"A crude way of phrasing it," he answered. "But you could not comprehend the reality."

He was laughing at me, though that round face of his with its strangely artificial skin was still as a modeled mask. He was—wait! I made a last attempt to cling to the explicable. I was in that dream again, that confounded dream. What I thought I heard him say was merely the reply of one part of my brain to the thoughts of another. I was imagining the odd being as I had imagined Evelyn Rand—

"Wrong. It was I who projected her before you. I wanted to check your reaction to the sight of her, to ascertain if it would correspond with what I had already observed, if it were constant or a sporadic aberration."

I could not have dreamed those words, for I had not the least idea of what they meant. I was beginning to be afraid....

"The hell you say," I flung at him to conceal my growing fear. "What am I, some kind of guinea pig you're experimenting with?"

A faint, mocking smile brushed his fleshless lips. Or did it?

"Exactly," he murmured.

That enraged me. "Experiment with this," I yelled, and leaped down at him, my fist flailing straight for his round, unhuman face.

My fist whizzed through empty air. My feet pounded on the floor. The little man had vanished—

SOUND behind me whirled me around. The fellow was on the

staircase, three steps up. He was exactly where I had been, an

instant before. But how in the name of reason had he got there?

He couldn't have passed me, he couldn't possibly have passed me.

To get to where he was he would have had to go up the steps at

the same time, by the same path, I had plunged down them.

"Matter can be in one place and then in another," he said in the slow, patient way of one explaining some complex idea to a child, "without ever having been anywhere between. Even you should know that. Or are you not acquainted with the observations on the behavior of electrons that already had been made in your time."

"In my time! What—?"

"The twentieth century, as you reckon it." I had the curious feeling that he was speaking of some period in the remote past. "I am certain our researches are correct on that point."

Mingled with my confused sense of wrongness about all this was a sort of baffled exasperation. Damn him! He was coldly amused by my bewilderment.

Yet no flicker of the muscles in his face, no changing light in his black and piercing eyes, revealed that to me. But I was as aware of his amusement as though he had laughed aloud.

Was I too, very dimly, beginning to learn to do without speech? Was I tapping some subtle current of communication that I had not even suspected to exist?

"Who are you?" I blurted out.

He was growing tired of this colloquy between us. "If you must think of me by a name, Achronos Astaris will do." He had stopped playing and was coming to the nub of his purpose with me.

"What, John March, is it that has impelled you to forget everything else in your desire to find Evelyn Rand? What is it that makes her a necessity to you, so that without her you are not complete? What is it that has made ambition, the anxiety for preferment, pride in the occupation you chose for your lifework, insignificant compared with the need you feel for her? What is it that draws you to her with a force greater than the attraction of gravity? What chemistry of the emotions has governed your actions since she became real to you?"

His dreadful, probing eyes demanded an answer. "I love her," I cried out. "God help me, I have fallen in love with her."

I had not known it till that moment, had not realized it. But it was true. I was in love with the girl for whom I had been searching so long, and never seen.

"Ahhh," Achronos Astaris breathed. "I know that the name of your reaction to her is love." For the first time I sensed a wavering in the clear, cold surety of him. "But what, precisely, does that mean?"

I stared at him, anger once more mounting within me.

"It is puzzling," he mused. I wasn't certain whether I heard Astaris say that, or whether I was reading his thoughts. "There is more than a physical chemistry to the emotion, although that is one of the factors. Plainly there is an urge—"

"Damn you," I shouted. Again rage drove caution from my mind. Blindly I leaped forward—and jarred against nothingness! Against a wall invisible, immaterial, but impenetrable as though a screen of inch-thick armor plate had risen instantaneously in my path.

Still senseless and unreasoning in my anger, I clubbed at that unseeable barrier with my fists. There was no sound of impact, but at once my knuckles were bruised and bleeding. I kicked, snarling, at empty air and saw the toes of my shoes buckle and split against nothing I could see. Exhausted, I shoved my palms against the wall and felt perdurable nothingness that was warm as though it were composed of animate flesh, that was vibrant, somehow, with a queer kind of life, but impenetrable as granite. I backed up and lunged at it shoulder first, and was stopped dead, seemingly in midair.

AT LAST I was aware of Achronos Astaris watching me with a

cold, mildly interested detachment, as some scientist might watch

a Siamese fighting fish batter its nose against glass of its

aquarium.

When I gave up finally and hung, panting and weak, against the invisible partition, he sighed. "You learned quite quickly. There is a definite improvement in five hundred years."

I stared at him, too choked by anger to speak.

Inexplicably, though Astaris was still clear and distinct, the staircase, the ceiling and the walls had faded again into the gray, shapeless blur out of which they had formed. I glanced down, terror rising in me now. There was only grayness beneath me. I twisted around. Nothing was behind me but a gray vacancy. I was enclosed by it, suspended in it. Once more the great fear of height possessed me, the heart-stopping realization of an unfathomable abyss into which I must plunge when Achronos Astaris released me.

For, wheeling again, I had found his eyes upon me, pinpoints of black flame, and I knew that only his eyes held me where I was. There was an impalpable Force in those eyes that reached through the strange barrier I had struck and embraced me.

And those eyes were not only holding me there, suspended. They were dissecting me, probing far deeper than my flesh, into my spirit itself. Like lancets they bared the hidden psyche, searching—searching for something that was there but which they could not find.

Wrath they found, and quivering fear, and an awed bewilderment transcending fear, but not the thing they sought. Gradually they faltered, at a loss. And then I was aware that Astaris had given up his search, that he was sending a message out into the boundless ether, that he was waiting for a reply.

I do not understand even yet, how I knew all this. I know only that for a little while I had the power, and that I was soon to lose it. At the moment I write these lines I would give all my hope of salvation if I could regain it.

"No," the answer came. Not a voice. Not sound at all. Naked thought from an infinite distance. "Send him to us, but you must remain yet awhile."

Astaris did not like that. I was aware that he did not, but I was aware also that he would submit. And abruptly my baffled fear flared into terror.

For now Astaris' eyes released me! Astaris himself was obliterated by the sudden motion of the grayness; it swirled about me, a dizzy darkness.

Yet it was not darkness; rather an absence of form, of color, of reality itself. I was falling through nothingness. I was caught up in some vast maelstrom and whirling through some spaceless, timeless non-existence altogether beyond experience. I was rushing headlong through distances beyond comprehension, yet I knew myself to be completely motionless. The Universe had fallen away from me, was somewhere behind me, light-centuries behind me. I was beyond life. I was beyond death. I was beyond being itself.

And all about me was the soft, voiceless whisper of swirling dust.

Argosy, 18 March 1939, with second part of "Seven Out of Time"

COMMISSIONED to investigate the disappearance of Evelyn Rand, John March, who is telling the story, is faced with a peculiarly baffling mystery. Soon, too, he discovers something else, to his own amazement—that he has fallen in love with this beautiful and strangely unworldly girl whom he has never seen.

But he manages to collect some rather odd scraps of detail from her life. There is the tiny amulet he finds at her home, graven in the shape of a snake. And there is the puzzling tale of Evelyn's old nurse: of how the girl walked to the road one day with the eagerness of one about to meet her lover, and yet was met only by a whispering whirl of dust.

EVEN more inexplicable is March's experience at the gallery

where a portrait of Evelyn hangs. Standing before the painting,

he is joined suddenly by a queer little man who begins to discuss

it with him. Then while the stranger speaks, it seems to John

March that the background of the portrait assumes for an instant

the immensity and the terror of all space. Deeply shaken, March

turns to the old man—to find him vanished. But he has left

something in March's hand—a card that bears the name

Achronos Astaris and an address in Brooklyn. From that

card there seems to come fleetingly a sweet, dream-like odor, the

perfume which John March has learned was the particular favorite

of Evelyn Rand.

At length March arrives at the address inscribed on the card. Inside the charming old house he believes himself to be alone—until he sees descending the stairs a girl dressed in the finery of two hundred years before. Her face is the face of Evelyn Rand. But before March can do more than cry out she disappears; in her place stands the strange little man from the art gallery.