RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

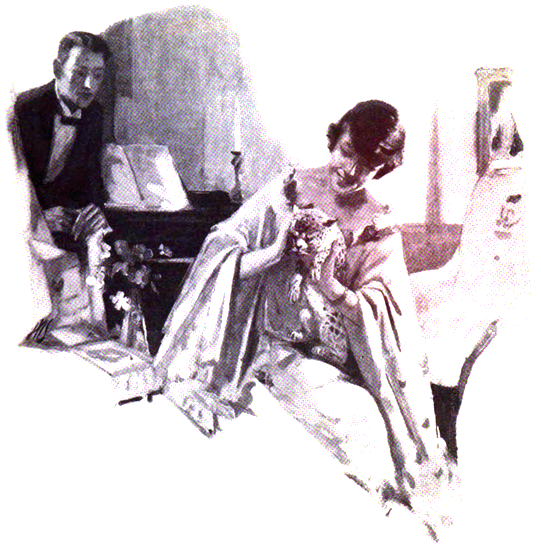

Cosmopolitan, November 1924, with "The Cat")

FRIDAY the 29th. I tried my best to fit in, but I'm never going to like this case. I can't even see that a trained nurse is needed here. What they could get along with much better, it seems to me, is a night watchman and a Swiss rubber rolled into one.

I thought, when Doctor Plainer first called me, that it was going to be a nice long surgical case, and that five or six weeks in the country would clear up what was left of my antrum trouble. I'd always understood that Platner did nothing but surgery. I never dreamed he was carrying me out to a "nervous" case, though I must confess that I was just a little dazzled when I found my patient was to be Verlyna Visalia, the great Verlyna Visalia.

She'd left the speaking stage, I think, before I came to New York for my training, and oddly enough I'd never even seen her on the screen. But I'd never cared much for that Babylonian type of movie which her managers starred her in, though I'd seen her photographs often enough in the magazines and read enough stories about her in the Sunday papers. And I'd had a glimpse at that rather awful portrait of her which stood in a Fifth Avenue window and interfered with traffic until her new manager got the court order to have it removed. Nor can I altogether blame the manager, in view of the fact that she'd more than once been spoken of as the most beautiful woman in the world.

Another thing that's kept me meeker than usual is the thought of getting enough money together to pay for my island up on the Muskoka Lakes. For fifteen years I've wanted that island with the bungalow on it. But I never dreamed that I'd have to come to a walled-in country place like this, where the wind moans through the pine tops and the iron gates make you think of a jail. I never really dreamed that within an hour's run of New York you could find a sepulchral old place like this, tucked away between wooded hills and so shut off from the outside world that the starlings and blackbirds made me think of Poe's "Raven" as I first drove in under the dripping trees on that rainy autumn afternoon.

I didn't like the look of the place and I didn't like the look of Ichikama. the old Jap servant who soft-footed about from room to room and needed almost a major operation to get a word out of him. And I didn't like the imperiously moody manner of my patient any more than I liked the heavy Oriental perfumes that hung about her room and made me think of a harem.

I've got more used to them by this time, I felt at first that some day they'd anesthetize me and I'd go under babbling about Agrippina and Lilith. And I had a suspicion or two of my own. It wouldn't be professional, I know, to say what those suspicions were. But I couldn't keep from wondering why a man of Doctor Platner's standing was taking care of my patient in the manner he did, motoring out from the city through mud and rain, placating her when she had one of her outbursts, and making it obvious that he preferred being alone with her for a while every visit.

It didn't take me very long, though, to find out I was on the wrong tack there. It wasn't anything as cheap as that. Then I switched to another suspicion and began to think that Miss Visalia was a drug addict. Heaven knows, there's enough of them about these days. And I'd learned to spot 'em, back in the hospital, as quick as a bank cashier spots a counterfeit. But my theory simply wouldn't hold water.

I learned that much, and a few things more, by the time I'd given my patient her first sponge bath. What a trained nurse can find out during that bath, indeed, is much more than the world imagines. Nor can I stick to the idea that my patient's being kept here to take any kind of cure. She's under no restraint that I can see. She has no drugs—she has asked for none. She doesn't even look ill. She's not ill. And I can't see that there's anything wrong with her mind except that she can become a trifle temperamental now and then, as any other over-flattered stage star is apt to do.

Yet in some way she's not entirely normal. She can't be. For no normal woman shuts herself away from the world as though she's taken the veil. And no normal woman is ever weighed down by her deadly kind of languor, which leaves her sometimes as though she were trailing a Scotch mist about her. She just lies and rests and idles about day after day like a woman convalescing from a hard operation.

I help her dress and she moves slowly about the room as though she were only half awake. And she smokes. She smokes more cigarette than are really good for her. Sometimes she talks and sometimes she sits up in her day bed, hour after hour, without moving or saying a word. Yet she impresses me at such times as being so warm and sleek and comfortable that she makes me think of a boa constrictor that's just eaten its monthly rabbit. But there's always something expectant in her slightly oblique eyes. She seems to be waiting for something. Just what it is I've no way of deciding. And she plainly resents any intrusion on her moods. She's as imperious, in fact, as one of the royal family. Or I ought to say, one of the Borgias, for I feel sometimes there's a wide streak of tyranny in her make-up.

But Verlyna Visalia is beautiful. And I think that portrait painter was stupid to try to make her ugly on canvas. She's so lovely that I'm beginning to understand how people can forget to resent being bullied by her—and I noticed last night that even Doctor Platner could eat crow if the occasion arose. It's a tropical night sort of beauty, and I can't help feeling that possibly pretty big fires may burn under the crust of her quietness. Perhaps they've even broken out, for there's history in her face, though it's history, just now, with the blinds drawn.

A woman like that, though, must have been loved by more than one man in her time. And her body is as beautiful as her face. I know something about such things. And she is vital, for her body seems to have none of the tiredness which creeps so often into her face. It makes me think of her, in some way, as a magnificent animal—when I really ought to be thinking of her, I suppose, as a rather neurasthenic woman who isn't sleeping quite as well as she might be.

For Verlyna Visalia is always more unsettled as night comes on. She insists on having a light burning and wants me in the room with her. And she cries out, now and then, in a nightmare. But I've never caught anything coherent in what she says.

The most amazing thing about her, however, is her vanity. It's as open and ingenuous as a child's. I've seen her sit for an hour studying her own face in a hand mirror. And whatever may have happened to her in the past, she must have found quite enough to feed that vanity on. For even here she has an odd stream of gifts sent in to her—books which she scarcely ever opens; baskets of fruit and brocaded boxes of chocolates which she tosses aside; armfuls of American Beauties with stems so long they have to come in what look like cardboard coffins. She opens them and glances over them listlessly and then forgets about them. I've noticed, by the way, that there's never a card enclosed.

I've seen her sit for an hour studying her own face in a hand mirror.

This afternoon, though, a different sort of gift was sent to the house for her. And I'm not surprised that it's shaken a little of the lethargy out of the lady. For it came in the form of a neatly woven hamper laced with rawhide. My patient regarded it indifferently enough when Ichikama put it down beside the Belgian grapes on the bed table. She didn't even make an effort to open it until, as I was braiding her wonderful double rope of hair for the second time, we both heard a muffled whimper from inside the hamper. She stared into space with wide open eyes for a moment or two. Then she asked me in that curt manner of hers to hand her the box.

She had quite a little trouble in getting the fastening of the lid free. But when this was done and she'd lifted the lid back, she stared so long down inside the hamper that, without quite thinking, I leaned over and had a look for myself.

All I saw there was a cat curled up in some fine moss covering the hamper bottom. It lay asleep between a rubber hot water bag and a baby's feeding bottle half full of milk. I was used to queer things in that house, but it impressed me as rather a foolish gift. I thought so, at least, until I saw my patient reach down and lift the cat out of the hamper.

I began to realize then that it wasn't an everyday sort of cat. It was a fluffy little four legged baby with pale amber-green eyes which watered at the strong light. It must have been very young, for it still carried a hurt and helpless look and doddered on its uncertain short legs when my patient put it down on her Venetian coverlet. She leaned over it, studying it intently. She even stroked the pale yellow fur closely freckled with darker spots and laughed a little as it meowed weakly, like a hungry kitten.

"What is it?" I asked, making no effort to hide my dislike for that frail and wobbly thing of mottled fur.

"It's a darling," she said as she held it up against the warm hollow of her throat. I don't know why, but it gave me a slight feeling of nausea.

SUNDAY the 22nd—I've been finding out

things about my patient. She's not nearly as exotic as

I imagined. Her family name, in fact, is the extremely

commonplace one of Fink, though she insists that her

mother was Roumanian. She manufactured the Verlyna and

took the Visalia from the California town in Tulare

County where she was born. She's to be excused for

this, I suppose, for a Hattie Fink could never have

become the woman of mystery that Verlyna Visalia has

been to the world.

Yet there is mystery about her. Last night I heard her call out the name of Julio Patoso in her sleep. And I've been wondering just who Julio may be. I've been giving her sponge baths every night about nine merely to tire her out and make her sleepy. She calls it her dry cleaning. I discovered, the first time I did this, that she had a small scar on her breast. It rather looks like a knife wound. At any rate I can still distinctly see the mark of the stitches. It's on the left side and disagreeably close to the heart. And I can't see how it was ever put there for medical purposes.

So last night I found the courage to ask, as casually as I could, how it ever came there. She looked down at it and massaged it with the tip of her finger. Then she explained that it had been done with a trick dagger in some of her picture work. The Spaniard who played the calif in one of her haremesque concoctions forgot to press the spring in a quarrel scene when he kills her for her unfaithfulness, so that the blade failed to slip harmlessly up into the handle. It was an accident, of course.

Then she went off into one of her brown studies and I felt it wouldn't pay to put any more questions to her. Whatever it was, I imagine the lady could always hold up her end in a quarrel scene. She has a temper like a wildcat, as I discovered this morning when she let out at old Ichikama, who stood as serene and unblinking under the lash of her temper as one of his painted ivory Buddhas. The only thing that moves him is this new cat thing about the place. He's plainly afraid of it.

Miss Visalia, I find, has decided to keep the animal which came in the wicker hamper. She fondles it and holds it against her skin and has even perfumed its woolly carcase and tied a ridiculous ribbon bow about its neck. She calls it her "Kitty," But it's no more a kitten than I am. It's really a two or three weeks old leopard cub. I suppose its new owner gets a sort of theatrical enjoyment out of having such a thing for a pet.

She fondles and cuddles it, but I don't believe she

loves the animal as much as she's like to have one think.

At first, when I saw her cuddling it to her bosom, I thought it was the play of a kind of suppressed maternal instinct on her part. But I don't believe she loves that animal as much as she'd like to have you believe. For yesterday I saw her lie and stare at the cub and blow cigarette smoke into its face. She would laugh when it wrinkled its nose and sneezed and wiped at its face with its clumsy little paw. It would even try to strike at her with its harmless padded foot. For that she would roll it on its back and rumple up its chubby body until it whimpered. It may not be cruelty, but there's something about it I don't altogether like. And following Ichikama's example, I'm not greatly taken with this idea of having a leopard cub about the place.

This afternoon when Miss Visalia sat so intently studying her pet I had a good chance to study her own face. She has a profile so clean cut that it looks metallic. Yet the lines, oddly enough, impress me as neither hard nor heavy. Her nose is so short and straight that it brings back to me some half forgotten picture of Cleopatra. There's something that strikes me as sort of half barbaric and half oriental too in the equally short and slightly out-curving upper lip. That part of her face has an air of half defiant levity which doesn't altogether go with the bitter curve of her mouth and the morose brooding of her wide-set eyes.

But it's the eyes themselves, I think, that are the most remarkable of all. For they're eyes that change quickly, both in coloring and character. They seem to have the power of turning at a moment's notice from a sort of opaque amber to a cloudy hazel, a hazel with a touch of raw gold in its inner textures. At the center of this amber and hazel, when the lady's a bit stirred up, the pupil gets large and glows like a cat's. And when she slumps back into her lazier moods I always feel there's something feline about both her body and her face. She seems catlike in her lithe sleekness, without either the softness or the cruelty of the cat.

Yet she's so self-immured and lazily fastidious about herself and so indolently watchful and unapproachable that I begin to feel she has something in common with the cat family. Perhaps that's why she's so taken up with this leopard kitten of hers. She seems to carry the same sleepy warning of quiet ferocities, of unexpected vitality in indolence. And she could show her claws, I imagine, if the reason for doing so arose.

SUNDAY the 15th—Doctor Platner is plainly

opposed to his patient's having a leopard cub about

the place. But when he suggested its removal Verlyna

Visalia so completely lost control of herself that he

had to withdraw his objections. And he did not care

to meet my eye on his way out. I wish, though, that

he'd been a little firmer in his stand. I don't care

much for life in a menagerie. And my patient is really

making this a menagerie.

There's something almost voluptuous in her delight in that tumbling and scampering bundle of fur. She coos over it when she gives it its bottle of milk. She carries it about in her arms and talks to it. She seems to love its soft and fluffy coat, its helpless clumsiness, its tumbling awkwardness. And it's sleek and soft and playful enough, coaxing for affection and still full of impishness. But I can't help thinking what it will some day grow into.

Even during the last few weeks it has changed. It is less a ball of fur and it now likes to bite at one corner of the bedspread. Once, too, I saw it give a feeble imitation of a snarl when its mistress cuffed its ears. And today, when it was put down on the floor, I noticed for the first time how it fell to sniffing and nuzzling along the door cracks. That gave me a stirring in the roots of the hair which I'd find it rather hard to explain. It seemed to carry a suggestion of jungle wildness.

Yet the illusion of this young animal being merely a house cat, a little bigger than most house cats, seems to die hard. Its mistress, as she fondles it, keeps repeating "Poor little kitty!" And she even lets its uncertain soft tongue lick her arm and her bare shoulder, shuddering with a sleepy-eyed delight as she feels that touch on her skin. And I find it hard to fight back a feeling of revulsion when I find the little beast asleep in the crook of my patient's arm, curled up against her breathing side exactly as a sleeping baby lies against its mother's breast. She has, I notice, begun to call it Sheava. And Sheava, I've also noticed, can purr like a cat. Yet this morning I saw the little beast standing up beside the bed doing its best to sharpen its baby claws on the hardwood post. It disturbed me in a foolish sort of way. just as my patient's growing habit of pacing up and down her room begins to get on my nerves. More than once, lately, it has made me think of an animal in a cage.

TUESDAY the 24th—I've been asking myself,

the last few weeks, whether I'm a trained nurse or an

assistant zoo keeper. Every day now Sheava, besides

its milk, has to have two lean mutton chops, which it

mangles disagreeably between its sharp young teeth. It

is slowly losing its round and pudgy figure and every

week seems to get leaner and more restless. It has

acquired the habit of nosing about the room corners

and sniffing about the doors, which have to be watched

and kept latched. It can also raise itself on its hind

feet, elongating its supple body as it investigates

chair seats and window sills.

It also has a liking for dark corners, from which it watches you with intent green eyes. Sometimes at night these eyes are all that I can see in the darkness. A few days ago, when I had to get Sheava out from under the bed, the little beast resented my interfering with its solitude and crouched back with its hair bristling, making catlike sounds at me. My patient laughed when it spit at me. Then she at once got out of bed and dragged her pet forth by the nape of the neck, cuffing it soundly for its bad temper.

But it was the thing that happened yesterday that got most on my nerves. A chimney swallow in some way fell down into our unused fireplace, and from there fluttered out about the room.

Sheava had been curled up asleep on the foot of its mistress's bed. But an odd change took place in it the moment it caught sight of that bird. It slunk into a corner and crouched there, with its amber-green eyes glowing and its little tail stiffened out like a hunting dog's.

It cowered there with its hindquarters rocking softly from side to side, waiting and tense and so ferocious-looking that Verlyna Visalia laughed as she lay watching it. She even started to talk baby talk to it, until I somewhat solemnly reminded her that a bird in the house was considered a bad sign. That seemed to sober her, and her face clouded as she watched the flying swallow strike flat against one of the window panes. Then the stunned bird flew low across the room towards the other window. But it never reached that window. Sheava sprang and struck up at it with a lightning-like paw, striking the poor thing down with its hooked claws and springing on it exactly as a cat springs on a mouse. The next moment I could hear it being crunched, crunched horribly, between those strong young jaws. I had to get out of the room.

The thing made such a disagreeable impression on me that I decided it was about time for me to do something. So I waited until Doctor Platner came. I stopped him downstairs and told him I couldn't see much use of my staying on the case. He has an amazingly well controlled face, but I could see a change creep into it as he asked me why I wanted to leave. I found the courage to tell him that I didn't feel it was a case calling for the services of a trained nurse.

He asked me, almost sharply, why I said that. I replied quite as acidly that there didn't seem to be much the matter with my patient. And at that he came out of his shell. He asked me to sit down and I noticed, in the strong sidelight from the library window, that his face looked older than usual. He almost pleaded with me to stay. He also protested that I was quite wrong about his patient. There were certain features of the case he couldn't very well go into, but Miss Visalia had been under a great strain and he knew of no one who could take care of her as discreetly as I could. I was needed more than I imagined. And if I'd be loyal to him in this matter he'd see to it that I—well, that I got less tiresome cases in the future and enough of them to keep me as busy as I wanted to be.

He was so in earnest about it all, and he was so generous in his promises about looking after me in the future that when he actually put his hand on my shoulder and asked me to stick it out. I weakened and told him I would. Then he surprised me for the second time by shaking hands with me and telling me I'd never be sorry for my decision. He is a great surgeon. I know, but for a few minutes there I saw him with the mask off.

That talk, however, has left me more than ever perplexed. There's a twist or two in this situation which I can't make out. I can't understand the mysterious strain under which this beautiful and indolent eyed patient of mine has been placed. And I can't understand Doctor Platner's exceptional personal interest in that patient. I've been wondering if even great surgeons, after all, are only human, and if he's learned to agree with the others who once called Verlyna Visalia the most beautiful woman in the world.

MONDAY the 13th—Its almost a month now

since I gave Doctor Platner my promise. And I'm

sorrier than ever I did it. For I've found out a

thing or two since then. Nurses usually do find

out a thing or two when they've been on a case as

long as I've been on this one. But a smoke-screen

had been kept over everything so neatly that I

was nearly startled out of my skin yesterday

afternoon—Sunday—when I opened my

patient's door and saw what I did. She was dressed in

one of her absurd ashes-of-roses negligées and stood

by a window staring straight before her. Kneeling in

front of her with his arms about her knees and his

head bowed as meekly as any stage Romeo's was my great

surgeon.

Visalia stood by a window staring straight before her.

Kneeling

in front of her with his arms about her knees was my great surgeon.

There was such abandon and such adoration in his attitude that I found it hard to believe this cool-eyed man of affairs could ever be so carried away. He did not see me as I stood gasping in the doorway. Nor did the lady herself, for the first moment or two. And during that moment or two I got an impression of her face which I'll never forget. It wasn't a look of surrender that I saw there, and it wasn't a look of triumph. It impressed me as a look of hunger, or perhaps I ought to say of hunger being satisfied. It reminded me of a purring animal king fed on something for which it stood waiting and famished. I don't like to say there was cruelty on that face with the staring, abstracted eyes. And it wasn't exactly hardness. But the kneeling figure seemed to be giving everything, and the standing figure seemed to be merely accepting it.

Being beautiful, she was permitting a man to worship her beauty. And she was cool enough about it all when she looked round and caught sight of me. There wasn't really a sound or a movement from her. She merely signaled me with her eyes. And that signal said to get away. So I backed quietly out of the room and just as quietly closed the door behind me. I don't know why it was, but I had the ridiculous feeling that I was backing away out of a man-eater's cage. Since then, I notice, my patient has been quietly studying me. She has made no direct allusion to what took place. But she has complained that men are cruel and has declared that nothing, after all can be more selfish than love. Then she asked me as naively as a child if I had ever been in love. I told her as steadily as I could that my life had been altogether too busy for romancing. She rather humiliated me by accepting that in perfectly good faith, remarking that women like that were always the happiest in the long run.

Then, remembering apparently that I'd already taken a step or two into the privacy of her life, she swung the gate a little wider and confessed to me that she'd recently gone through a very unhappy affair. It had burned up the best of everything that was in her and had left nothing but ashes. And it had been tragic, as well, to others. Then she looked at me with her abstracted and slightly oblique eyes and remarked that I was, of course. Anglo-Saxon, and that I probably wouldn't understand. But she warned me to be very guarded with men of the Latin race. They took such things so seriously. And they could hate quite as fiercely as they loved.

I listened meekly enough. But I can't help wondering who the mysterious Latin may have been. I was even tempted to ask if his name was Julio Patoso. Instead of that, however, I followed another plan. I waited until Doctor Platner's next visit and when he asked me the usual questions about my patient I stated that she hadn't been sleeping very well.

"I heard her call out the name of Julio Patoso," I truthfully enough informed him. And I watched his face as I said it. He keeps that face pretty well under control, but for a moment and no more I caught the cioud that flitted across it. The name, whatever it may have stood for, carried a distinct message to him. And the sound of it couldn't have been pleasant in his ears. He merely said, however, that he'd leave a sedative for his patient. I was bold enough, at that, to ask if it wouldn't be belter for everybody if the leopard cub were taken away from the house.

"Yes, for God's sake get rid of it," he cried out with quite unlooked-for intensity.

"That," I reminded him, "will not be an easv thing to do. Doctor."

He let his eye meet mine.

"I know it," he acknowledged with a frustrated look on his face. And that's the satanic cleverness of the man."

"Of which man?" I asked, startled and altogether at sea.

"Patoso, of course!" he snapped out as he turned away.

SUNDAY the 26th—If I can't quite understand

what Doctor Platner was driving at, I've at least come

to understand that Sheava is not to be got rid of.

Verlyna Visalia grows more and more attached to that

pet of hers, which she has fallen into the habit of

teasing in an entirely new way. She lifts it up on the

bed and confronts it with her polychrome wall mirror.

The cur bristles and snarls and strikes at its own

likeness in the looking glass. It even grows canny and

cowers back and tries to out-maneuver its mirrored

image by striking at the back of the frame with its

hooked claws.

I hate to see the thing soft-footing it through the rooms, with its amber-green eyes on everything that moves, ready to stalk it. It seems more restless at night, and I've even got to dreaming of a silent and padded figure with a mottled back staring out of the darkness at me and weaving its lithe body snakily about one corner of my cot. I tried to explain to my patient that all animals in captivity need quiet and darkness for sleeping and that Sheava would be much better put away somewhere for the night. But the imperious lady on the lied wouldn't hear of it. "Sheava's my guardian spirit!" she foolishly asserted.

Sheava may be her guardian spirit, but I notice a less mysterious one had been added to this ménage. A sullen giant named Howden has been installed here as a watchman. He prowls about the grounds by day pretending to be a gardener. At night he closes and locks the big iron drive gates and nobody goes or comes without passing under his observation. The discovery of this mysterious man on duty down there depressed me more than I'd be willing to admit. It makes the place seem more than ever like a jail. But a foolish idea has crept into my head. And I can't get rid of it. I mean about all these precautions and watchings and withdrawals from the everyday world. I begin to feel they exist, not to keep something in, but to keep something out!

SUNDAY the 19th—Now that Spring is here,

Verlyna Visalia seems better in spirits, and even

comes out now and then and paces moodily on the path

of the sunken garden.

She has, however, been having trouble with Sheava, who grows sulkier and more intractable every day. A few nights ago, indeed. Sheava escaped from the house, and a fine time we all had of it, combing the gardens and the shrubbery for that lost cub. Howden brought me a flashlight and dog-whistle, and told me to go along the east wall. I was to blow for him if I saw anything. I found a garden rake and went poking through the bushes, stopping short at every shadow, with my heart pounding at every sound of the wind in the trees and a tingle going up and down my spine at the rustic of every dead leaf along the ground.

Howden found Sheava in the abandoned chicken coop, lying on his back and playing with an empty wire nest as a kitten plays with an empty spool. His mistress showed a tendency to laugh at us for all the fuss and feathers we'd stirred up over her pet's visit to a hen house. But I noticed today she wasn't so quiet mannered when she discovered that Sheava had found her gray squirrel cloak where it hung in her closet and had torn it down and ripped it to shreds. Verlyna Visalia has, in fact, ordered Howden to get her a heavy dog whip. It's about time, she's announced, that this cub finds out who's to be mistress round here....

Saturday the 20th—Two months have dragged

away and up until tonight everything has gone on about

the same. But tonight, for some reason or other,

Doctor Platner and my patient quarreled. I have an

idea it was over Sheava. But I can't be sure. At any

rate, Doctor Platner is going to discontinue these fly

by night visits of his. He has, however, given me the

number of his private telephone and at eight every

morning I'm to call him up.

I might tell him tomorrow that my patient paced her room tonight for three solid hours exactly like a panther pacing its cage. But I don't think I'll give my cool-eyed Doctor that satisfaction.

Much as I dislike this mottled cat thing that prowls around here, I must acknowledge that he's growing into a beauty. He has lost his cub-like clumsiness and every move he makes now is graceful. There's actual splendor about his lithe body when his mistress lets him out in the garden and he bounds across a stretch of open space. He simply undulates, likes the waves of a smooth and oily sea. The blunt nose look has gone from his face and his eyes have deepened in coloring. His pelt is truly wonderful, and I begin to understand the idly voluptuous delight Verlyna Visalia takes in smoothing it with her gold backed hairbrush. I've noticed that under the hide now you can see the running muscles rise and flex.

Our Sheava, too, has developed a distaste to being handled. He is capricious and moody and has to be watched every moment of the time. His mistress, it's plain to see, resents this. She still wants to baby the brute. She has taught him to leap through her arms. Yesterday she tried to tie a herring-gull turban over his head. Sheava with great despatch ripped it to pieces. But his mistress was not angry. "Won't New York sit up," that foolish woman demanded, "when Sheava and I ride down Fifth Avenue on the same auto seat!"

SUNDAY the 2nd—Another six weeks have

slipped past. Until today nothing much happened,

except that the hot weather rather burned up my garden

and my g.p. has twice made me ridiculous gifts of

jewelry. But the heat, I think, has got on everybody's

nerves. And there was a real outburst here this

afternoon. Somebody about two weeks ago sent Verlyna

Visalia a Pomeranian pup. I'm not sure but I have a

vague suspicion it was Doctor Platner. My patient was

never greatly taken with the pup. There were even

orders that it should always be kept downstairs. But

this afternoon Sheava got loose—and the trouble

began. We were all started off on the customary mad

hunt. Howden, as usual, was the first to discover him.

This time he turned out to be stealthily stalking

something, which turned out to be the Pom. I heard

Howden's shout and when I got up to him I saw the man

strike the crouching leopard cub on the back. He used

a pick handle, and struck with all his strength. But

it didn't keep Sheava from springing.

The pup was dead, of course, before any of us could do anything. And there was no way of keeping the news from Miss Visalia.

She was terrible in her rage. She turned white, and said there'd be no more of this kind of work. Then she shut Sheava in her room and got the heavy dog whip. She wasn't in the least afraid of the animal, even when he'd try to spring at her. She lashed him unmercifully. She lashed him across the back, across the neck, across the face. When the whip stung his haunches he'd turn quickly and try to lick first one wound and then another. But the whip never stopped. It writhed about the snarling nose. It flayed the glowering green eyes. It cut until the blood showed in places. And this kept up until the leopard cub could only claw blindly at the air, whining and cringing. He finally gave up and groveled on the floor, loose-lipped and drooling, whimpering for mercy.

She was terrible in her rage... She lashed the yellow haunches,

flayed the animal's head with its glowering green eyes

I hated to see it, and I hated to see that woman's face, so white with passion. "That's something he'll remember," she said, coolly enough, when it was all over. And it's something I'll remember, I'm afraid, much longer that I want to.... But I've found Howden's pick handle and quietly carried it off upstairs and hidden it behind my closet door. I feel safer with it there.

THURSDAY the 6th—My patient, during the

last three days, has not been resting well. She calls

out in her sleep and last night I distinctly heard

the name of Patoso again. That prompted me to make a

suggestion today. I took the bull by the horns and

asked why we shouldn't all have a change of scene, why

we shouldn't try a few weeks up at Lake Placid or even

ten days down at Brielle.

My patient said it was quite out of the question. I naturally asked her why. And then she studied me for a few minutes, after which she began to talk. She told me she was there because her life had been threatened. There was a man somewhere out in the world who'd sworn to kill her, a passionate and reckless man who'd stop at nothing. But luckily he was dying. Almost a year ago they'd told her he'd have only a few months more.

I asked her why he should be dying. I really wanted to work my way closer to this mental delusion of hers, this megalomania which persuaded her men were going down like nine pins because of her beauty. She studied me again with those abstracted eyes of hers, and said that he'd once shot himself through the breast, and had tried in a moment of depression to commit suicide. He had missed his heart but the wound in the lung had brought on tuberculosis. He'd never recover. But always, so long as he was alive, she'd be afraid of him.

I took it with a good sized grain of salt And I'm still inclined to take it that way. I've seen these nervous cases before. And I've had more than one tall yam dished up to me on the platter of plausibility. It shapes up, to me, as the excessive vanity of the woman morbidly feeding itself on evidences of her own importance.

SUNDAY the 10th—Now that autumn is here

again and the days are growing shorter and the night

wind whines in the pine trees, I find myself getting

unaccountably restless. I'll be glad when I can break

away. I don't altogether like the way Sheava has

been acting the last few days. In the morning when

I telephone to Doctor Platner I intend to tell him

so. It's beginning to get on my nerves, having that

musky-scented jungle pet under the same roof with me.

Sometimes, when for an endless stretch of time he lies

crouched down on a rug, tense and taut and motionless

and ready to spring, yet never springing, I want to

stand up and scream.

TUESDAY the 19th—The unexpected has

happened. My case, apparently, will be over sooner

than I looked for. La commedia e finite, as Verlyna

Visalia remarked. For this morning she received a

newspaper from Mexico City announcing the death of

Julio Patoso. She's like a woman reborn. She's had her

trunks hauled out and even called up Doctor Platner.

He's to come out Sunday. And there was actually color

in her face when she hung up the receiver. Ichikama

himself, for once in his life, has become garrulous.

And my patient dressed without my help today. She's

suggested, in fact, that we try a hike over the hills

tomorrow. Even a well-trained nurse, I'm forced to

admit, can occasionally be wrong in her diagnosis!

THURSDAY the 21st—We didn't after all have

our walk over the hills. Something sadly different to

that has occurred.

Just after breakfast my patient, who'd been going over her gowns, said she wanted Sheava brought to her room. I remembered a convenient task downstairs when Howden was told to bring the brute in, for I've been more than ever afraid of Sheava lately.

I don't know how it started. I don't suppose anybody ever will know. But I'd come upstairs again and was just swinging the linen closet door shut when I heard that repeated shrill scream from Verlyna Visalia's room. I knew something was happening, something I dreaded to face. But I had sense enough to run to the stair banister and shout down to Ichikama, calling frantically for him to come, for Howden to come, for anybody to come. That craven Jap must have heard me. But he neither answered nor appeared. So I set my teeth and ran back to my patient's room and swung open the door.

I saw her standing there with her back to the wall. She still held the heavy whip in her hand. But her face was white and her eye wide and staring. On her bare shoulders I could see two narrow streaks of blood running down towards her breasts. In the center of the floor I could see the leopard. He was crouched low on the rug with his lean body taut and his tail moving slowly from side to side. I could see that he was ready to spring

And something told me that if he did it would be terrible this time. So I ran to the closet where I'd hidden away my pick handle. I'd no idea of exactly what to do. But it's an instinct with a trained nurse to protect her patient. Without stopping to reason out why, I raised my pick handle and brought it down with all my strength on that cowering lean back. I might as well have pounded a pillow. That crouching big cat paid no attention to my blows. It was plainly a matter of personal hate, a matter between him and the woman against the wall.

I was still pounding at him when he sprang. Both he and the woman seemed to scream together, in a cry oddly alike, as he leaped for her throat, for her face. And they fought and went down together, a flurry of white and yellow.

It sickened me. But I remembered that all such brutes feared fire, could be fought with fire. And I remembered the bottle of grain alcohol on my supply table. So I ran for the bottle and caught up on my way a pair of silk stockings and twisted them around one end of my pick handle. Then I drenched them with the spirits. My hands were shaking so that I had trouble in lighting a match. But once I'd touched the flame to that dripping mop it caught fire. I held this against the maddened brute's body. I slashed his writhing back with it I kept at him until the smell of scorching fur became sickening.

But he never let go. I could see his flexed body quiver with pain. But he never turned round to me. I could hear him gag with the fumes. But he refused to release his hold.

Then I lost my head at the horror of it all. I think I began to scream. I was beating foolishly at the mottled yellow haunches when Howden came on the run and pushed me to one side. He had a blunt blue automatic pistol in his hand, and he dropped on one knee close beside the two faces that lay so close together. I could see him push the blunt barrel close in against the furred body, just at the base of the straining neck.

It made less noise than I expected when he pulled the trigger. But he'd been sensible about it. There was no need for a second shot.

My voice was still shaking when I telephoned for the local doctor and also to Doctor Platner. When I got back to my patient's room I found that Howden had lifted her up on the bed. He'd put a towel over her face, and for a moment I thought she was dead. But I soon found her pulse and got busy on my first aid work. When, to give respiration a decent chance, I lifted away the towel, I understood why Howden had placed it there. But I didn't understand, at the moment, what Doctor Platner meant when I met him breathless on the stairway half an hour later and he gasped: "So our dead Patoso wins, after all!"

SUNDAY the 8th—After all my waiting the

case has at last become an interesting one. Doctor

Platner is doing one of the neatest pieces of surgery

I ever clapped eyes on. Two weeks ago a section of

flesh shaped to the form of a lower lip was cut on

Verlyna Visalia's forearm and a grafting juncture made

with the lip base. The arm was then bound up about the

head and held there until the graft seemed assured.

Today, when we carefully took away the dressings,

enough adherence had taken place so that the section

could be severed from the forearm and shaped like a

lip.

The same procedure will now be followed in restoring the right half of the upper lip. Then as soon as our patient is strong enough for another operation he'll cut a piece of healthy cartilage from one of the ribs at the juncture with the breastbone and with it build up the nose, slitting the skin and drawing it over the bone as the healing process goes on.

The skin grafting along the torn cheek flaps has been really wonderful. It'll leave scarcely a mark. And this afternoon that magic-fingered surgeon told his patient he was making her back into the most beautiful woman in the world. But I noticed two tears run down the white cheeks with the stitch scars still in them. Then she reached for his hand and hung on to it for dear life. And then, right in front of me, he so far forgot himself as to push back that still gorgeous hair of hers and kiss her on the forehead.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.