RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

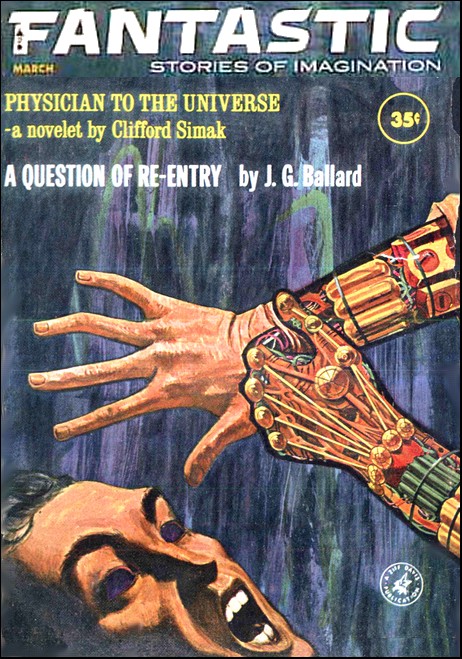

Fantastic, March 1963, with "His Natal Star"

MY name is Jules Bertraud. I have lived in Paris all my life.

It is the first time that I have ever been in conflict with the

police—the first time I have ever been arrested. As my

sanity has been called in question, and you, Monsieur Barbierre,

justly distinguished as an advocate, have kindly undertaken to

defend me, I send you this truthful history of the circumstances

which have led to my being thus imprisoned as a lunatic.

I have purposely applied to you to conduct my defense, as you are not alone learned in the law; but have spent, like myself, whole nights in studying the complex systems of the stars, which but yesterday were under my feet, and to-night, as I write this in my gloomy cell, shine so brightly overhead.

Perhaps you may have never noticed a small star of about the thirtieth magnitude, which, on very clear nights and with a powerful telescope, may be discovered almost midway between the constellations of the Pleiades and Ursa Major. It is the comparatively insignificant star called Perigo. It has a Portuguese name, an ominous one, signifying "peril," "hazard," "jeopardy." It is my natal star. Born under its direful influence, I have been subjected to it ever since. My father, who was, as you know, a celebrated astronomer, has calculated that its orbit is so vast that it takes it nearly fifty years to complete it. His last words to me were: "Beware of Perigo when in perihelion. It will then possess its greatest power over you for evil. What effect it may have upon you at that time it is impossible to surmise; something, however tells me that it will materially change not only your mental but your physical being.

That warning was uttered fifteen years ago. I have never forgotten it. Pursuing, like my father, the study of astronomy, I was enabled to watch through the long nights the steady, irresistible approach of that fateful star which was to have such an influence upon my destiny.

You are well aware how I have struggled against it. Sometimes I have dreaded that it would tempt me to the commission of some fearful crime. Dwelling on this, what wonder if my mind should have assumed a morbid cast? But I am not insane.

I could confide in no one. You, the successful advocate, and I, the obscure astronomer, had not then been linked in the bonds of friendship through our simultaneous discovery of a new planet. My wife's relatives, ever on the watch to secure some pretext for her separation from a man who brought her but little fortune, I could not trust. Even from my wife herself I concealed my growing, appalling apprehensions. It is perilous to confide a secret to woman.

TWO weeks ago I insensibly became aware of the near approach

of my natal star to that great center of the solar system which

ordinary men call the sun, but which to us is merely one of many

planets around which systems of far greater immensity than ours

revolve. It was then that I set myself to a calculation of the

exact time when, in accordance with the inexorable laws of

nature, the star Perigo would attain its perihelion with the sun

of our system. A long series of calculations had assured me of

the fact that at or about midnight of the 17th of October, Perigo

would be in the zenith.

A prey to the profoundest apprehensions, I at ten o'clock that night bade my wife good-night, and, stooping over the cradle of our youngest-born, imprinted upon its forehead what I thought might be perhaps my farewell kiss. I then shut myself in my study, closed the door tightly, and sat down to wait, unaided and alone, the coming of the fateful moment.

To divert my mind as much as possible from thoughts of the impeding disaster which I felt certain was about to overwhelm me, I plunged at once into the solution of a problem which had already caused me many sleepless nights. While thus engaged, overcome with fatigue of watching, I sank into a profound slumber I dreamed that I had been suddenly taken very sick; that physicians had been called in; that I had died and had been stretched out upon a board for the purposes of an autopsy. The hardness of the bed upon which I had thus been laid disturbed my slumbers. I awoke, rubbed my eyes, and sat up. I did not at first realize where I was, or the extraordinary things which had happened to me. I looked around. It was the same room in which I had gone to sleep. The paper on the wall was the same, to the very pattern. But the room had been stripped of furniture, even to the carpet, and the floor had been whitewashed. How long had I been asleep? I stood up and walked to the window. I had left the top of it open for ventilation. My study, as you know, is a very lofty room. Whoever had divested it of furniture had also closed the window at the top. To compensate for this he had opened it at the bottom I leaned over the sill and looked out. The stars were shining far away below me; yet the noises of the street, which are never absent in Paris, no matter how late the hour, fell distinctly upon my ear. Again I glanced below, completely mystified. There, shining in the azure depths, were the silver, twinkling stars, the familiar companions of my vigils. The earth seemed to have melted beneath my feet.

A dreadful feeling now took possession of me. Trembling violently, I fell upon my knees upon the hard, whitewashed floor and prayed fervently. I shut my eyes to keep out the horrid visions which oppressed me. Was I going mad? By degrees I became calmer. I opened my eyes and cast them heavenward, and the next moment had sprung to my feet again, staggering back, open- mouthed, wild-eyed, appalled. Above me, not forty feet away, was the pavement of the street in which I resided. Upon its stony surface men and women walked, head downward, in the air, and vehicles of all kinds passed by me in a singular procession, the quadrupeds engaged in drawing them appearing like flies on an exaggerated ceiling.

Still I did not comprehend. While my mental faculties remained unimpared, my brain was slow to appreciate the marvellous change which had taken place in my physical constitution. It was not until I withdrew my head from the window and glanced upward that I began, faintly at first, but soon with all the intensity of my being, to realize that prodigious thing which had happened to me.

ON the ceiling of the room, all the furniture of the apartment

was arrayed precisely as I had left it two hours before when I

had fallen asleep. There was the desk with the inkstand into

which I had dipped my pen. There was my heavy arm-chair, my

stove, a ponderous weight, which I wondered did not fall and

crush me; my bookcase filled with books. Amazed, I looked at all

these things. Even the cat slumbered on the hearth rug.

How did she do it, seemingly holding on to nothing, in a chamber which had been literally turned upside down?

Then suddenly an awful thought flashed across me. Instinctively I pulled out my watch, holding it open in my hand. To my amazement it slipped from me and like a balloon rose to the level of my chin. I caught it and pulled it down. It was just at the strike of midnight.

It was the fateful hour. Perigo was in perihelion.

Brought under its tremendous influence, the pitiful attraction of the earth had been easily overcome. What my father had dreaded and dimly foreseen had come to pass. Henceforth I was released from the influence of the earth. The gravity of Perigo, in my single instance, was all-powerful. Like a flash the real state of the case darted through my mind. I, not the earth, nor the house upon the earth, nor the room within that house, but I, Jules Bertraud, was walking upside down.

My soul was seized with a sudden panic. Rapidly I walked up and down the ceiling. As I moved, coins, keys, and various articles fell rattling from my pockets. A five-franc silver piece struck against the lamp. If it had broken it I could not have descended to extinguish the flames. Heat ascends. It was stifling where I was, notwithstanding the open window, near which, indeed, now realizing the awful influence of the star, I did not dare to venture, fearing that a false step might precipitate me into those tremendous depths that, like a fathomless ocean, gleamed beneath me.

I took off my coat and laid it upon the whitewashed floor. The moment I took my hands from it it arose rapidly and struck against the carpeted ceiling. The cat woke up and ran and nested in it. I cried "Shush! Shush!" It looked up or down—whichever is right—and ran under the desk, fearful lest I might fall and crush it. I, on my part, stood staring stupidly and wondering why it did not fall into my outstretched arms.

I experienced no unpleasant consequences, physically, from my novel situation. My body, however, seemed to have grown much lighter. It seemed as if I could not weigh more than fifty pounds. My blood flowed naturally in its channels. I was feverish, but that was from the heat of the chamber. I leaned out of the window and felt the cool breeze upon my fevered cheek. I gazed again into the eternal depths below. There, midway between the Bear and the Pleiades, was my natal star. I had but to leap from the window to be carried at once toward it. Of what interest I might be to science if I could reach it! But I should never return, or if I did, it would be when Perigo had passed its perihelion and then I should be hurled back to earth a shapeless, indistinguishable mass.

I BECAME seized with a sudden desire to leave my study. I

walked over to the door, but it was far above my head. The

transom, however, was open; by a desperate spring I reached it,

drew myself up easily, and crawled through. Arrived on the other

side, I hung for a moment by my hands and then let go. It would

have been dark but for the moon, whose mellow light came through

the glass roof of a covered passageway against which I had

dropped. Had I been of normal weight I must have crushed through,

and then nothing could have saved me; but as it was, the thick

glass roof of the passageway easily sustained me.

I was moved by an indefinable instinct to go forward. You may think it was a curious journey, thus to be wandering around one's own house upside down, walking along the ceilings; but the world to me was upside down, and the only thing that appeared to me to be at all ridiculous was the fact that the earth, the houses, and the people in them were all upside down. I wondered how the people could breathe, and why those houses, horses, and carriages did not detach themselves and fall into the deep abyss.

I reached the end of the hall and passed out on to the ceiling of the stairs. I worked myself down to the wall of the staircase, looking up every now and then at the pattern of the carpets. I crossed the hall, stumbling against the chandelier. Several of the crystals were detached and fell to the pavement with a loud crash.

Pierre, the butler, who always sleeps in the little room to the right of the hall, woke up and came out, candle in hand, rubbing his eyes sleepily. I trembled with fear, and dared not move while he went through the rooms with his pistol, looking for robbers. At length he satisfied himself and returned to his chamber.

I now desired to escape from the house. The hall door was entirely beyond my reach; but again I could have resort to the transom. If I could only reach the railings outside I might work my way along them until I met some one. I felt an inextinguishable longing to be with you, the only man to whom I could explain my strange case, and of whose sympathy I could be certain.

With much effort I forced the transom, and creeping through, I hung for a moment by my hands. I dared not look down into the fathomless abyss. A single glance would have destroyed me. Wisely I forbore, and commenced to climb up in the direction of the street railing. The inequalities in the woodwork and my light weight favored me. The next instant my hand grasped the iron. I drew myself up until my head touched the stone coping, and planting my feet upon the ornamented finish of the fence, I worked my way along the street.

IT was now nearly two in the morning, and I am satisfied that

I should have reached your door in safety if I had not, in

turning the corner, had the misfortune to be espied by a

policeman. This man, as you know, seeing me standing on my head,

thought me a maniac. He called up another policeman, and despite

my entreaties I was carried off to the station. Being turned

around what they thought was the right way, despite my attempts

at explanation, in the hands of these ignoramuses, I narrowly

escaped suffocation.

Conducted to the police station, they threw me into a cell, where I fell with such force against the ceiling that I lost my senses. When restored to consciousness two hours later I found myself sitting up on the floor. The influence of Perigo had passed. I was again subordinate to the law of terrestrial gravity.

This, my dear Monsieur Barbierre, is a brief outline of my adventures. To you, who know my family history and the vindictiveness of my wife's relatives, I make this confession. As a man who reveres the truth and knows the incredulity of the public, you will see the futility of stating the exact facts in the case. I should never be believed. Worse, should I publish what I have here written, I should undoubtedly be adjudged insane.

I beg of you to exert, therefore, your inexhaustible ingenuity in rescuing your brother scientist from his present predicament without betraying his secret. Do this, and forever deserve the gratitude of your devoted friend, Jules Bertraud.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.