RGL e-Book Cover

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

The Popular Magazine, 20 Dec 1922, with

first part of "The Mann With Yellow Eyes"

"The Man with Yellow Eyes," George Newnes Ltd., London, 1923

"The Man with Yellow Eyes," George Newnes Ltd., London, 1923

"The Man with Yellow Eyes" is a pulp adventure mystery featuring Smiler Bunn, a charming rogue with a knack for getting into—and out of—trouble. Set in England, the story revolves around Bunn and his companion Fortworth as they attempt to protect an American heiress who has recently moved into Harchester Hall in Purdston. The plot thickens with the arrival of the mysterious "man with yellow eyes," a figure tied to the era's xenophobic "Yellow Peril" tropes, which were common in pulp fiction of the time. The novel blends suspense, action, and period-specific intrigue, all wrapped in Atkey's signature style of witty dialogue and fast-paced storytelling.

It's worth noting that the book contains outdated and offensive stereotypes typical of early 20th-century pulp literature. If you're exploring it today, it's best approached with a critical eye toward its historical context.

Frontispiece

Mystified, Mr. Bunn stared in, listening intently.

MR. "SMILER" BUNN finished his second glass of costly pre-war liqueur brandy, sighed loudly for no apparent reason—unless it was because he and his friend and partner, ex-Lord Fortworth, were at the useless end of a careful and painstaking lunch—and lit a cigar that was worth far more than its weight in real money.

"No, Squire," he said, good-humouredly, with the air of one who maintains firmly a previously expressed opinion, "I am a man who has been gifted from birth with a remarkable talent for getting at the essence of things. The core of the apple, so to put it. I am, as a rule, gnawing at the core of a thing before an ordinary man like yourself has begun to find his way through the crust. You may have noticed that about me. Probably you have. It's not a thing I brag about, because it's as natural to me as—as, well, say the size of your feet are to you."

He started on his third liqueur and continued.

"But what really makes us melancholy, Squire, is the fact that there is more going out than is coming in. We're spending money by the half-bushel—we're earning it by the half-pint. If that. We want to think of some way of getting back to the old busy life when hardly a month passed by without a chance of some little rake-in and a trifle of healthy excitement. We've had very little of either lately, and we want to pull ourselves together and get busy."

"How?" demanded that somewhat dour-looking individual, ex-Lord Fortworth (more generally known to his friends as Mr. Henry Black).

Mr. Bunn smoked in silence for a moment. Few people, glancing at his heavy, red, good-humoured, closely-shaven face, would have credited that he was one of the deftest and most successful chevaliers d'industrie in London.

He removed his cigar at last and answered slowly.

"How, Squire? How shall we get busy? I can't tell you—in spite of my great natural gifts. But I've just had a hunch, a fancy, come floating into my head, and perch on the edge of my brain, that we are not so far off a bit of big business. How, when or why, I don't know. It's instinctive—a bit of my natural genius sticking out."

"Like the tail of a tramp's shirt," said Lord Fortworth, sourly.

"Well, that ain't altogether the most elegant way of putting it," observed Mr. Bunn, stiffly. "But—in a low sort of way—you're about right.... And between ourselves, I shan't be sorry. We've been running to seed and you are putting on flesh at a rate that would get me scared. You know your own business best, n'doubt—but it would be a good thing for us both if something cropped up to keep us active on our legs and busy in our minds for a time. However, we shall see."

He helped himself to another cigar.

"I can smell money and excitement as far off as a nigger can smell water-melon," he declared, speciously, "and I've got an idea that there's a flavour of both in the air!"

But Fortworth only laughed with a touch of morose scorn.

"That's simply because Harchester Hall, down at Purdston, has been bought by old Whitney Vandermonde for his heiress to enjoy a year or two of life in England. Anybody with any human feeling would catch a flavour of money in the air if the niece of one of the richest men in the world chanced to settle down more or less next door—as she has with us. If I am any judge of things, our little place at Purdston will reek of money before long. The lady took possession last week, didn't she? That's why you've caught a flavour of money in the air. My advice to you—the advice of a plain man, without any frills, and without any damned fancy natural gifts—is to "

But here he broke off suddenly as his partner turned away and rose to greet a lady who, apparently leaving the dining-room, had caught sight of them and deflected herself in their direction.

She was an extremely good-looking woman with red-hot hair, an impossibly perfect complexion, notable eyes, and an excessively self-possessed manner. She was alone, but gave off without the slightest difficulty a marked impression that she was entirely capable of taking the greatest possible care of herself—if she wished to.

"Of all the friends I have in town, you are the two I most wished to see," she said in a deep, cooing, pigeony contralto. "I am going to sit down and break some very good news to you over a cigarette and a liqueur. I am your fairy godmother to-day. I was just going to call at your flat."

Mr. Bunn's smile decreased slightly. He knew Mrs. Fay-Lacy quite well enough to be very definitely aware that she had never yet fairy-godmothered anybody in her life but herself, and, as he put it later to his partner, she probably charged herself a ruinous fee every time she had done even that.

But he was usually ready to listen to the prattle of a lady after a good lunch, and he made her welcome.

"That's what we like about you, Esme, my dear," he said easily. "Ever on the look-out to do somebody a good turn. Don't you ever think of yourself at all—ha-ha!"

She flashed a glance at him. , "Not half as much as I ought to—in a city like this," she claimed, and lit her cigarette.

"How is business?" inquired Mr. Bunn—for the vivacious flame-crowned lady, in spite of her god-motherly weakness, was by no means one of the drones. She had long ago struck out for herself, and, Mr. Bunn believed, had continued for some years past—ever since parting for ever with her husband as the result of a decision given in the middle department of the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division—to maintain herself in extremely comfortable circumstances as an agent—representing Mr. Craik Lazenger, the celebrated money-lender. There were not lacking sardonic folk who referred to the striking Mrs. Fay-Lacy as the Money-Spider, but it was the pleasing custom of Mr. Bunn and his partner to "take people as they found them," and since she had never fallen into the foolish error of mistaking the partners for flies, they were the best of friends.

"Business? Oh, you mean the financial agency," crooned the lady. "I've given that up—practically. Everybody wants to borrow money, but nobody has anything but the quaintest kind of security to offer.... I can always arrange a small matter for anyone on reasonable security, of course. But it's about another thing I wanted to see you."

She thought for a moment.

"Did I dream it or haven't you told me at some time or other that you've a funny, ramshackle, tumbledown, old country house on your hands somewhere down near Purdston?" she asked.

It was the partners' turn to think. For it was at Purdston, a very quiet, scattered village, on the Surrey-Hants border, that they had long maintained a very cosy and secluded little country house, to which they often fled for recuperation after their life in London, or change from their town flat. Very few people knew of this, for they were not men who took any very keen delight in talking at random about their private affairs.

But evidently the fire-crested fair one before them knew of it.

Mr. Bunn nodded slowly, with the air of a man who suddenly remembers something.

"Why, yes, we have—a bit of a bandbox of a place. Why, my dear?"

"I happen to know of someone who would be willing to take it off your hands, if it's a nuisance to you at all," cooed Esme. "They want to live down there, and there are very few houses to be had in that neighbourhood. They would pay a little over the market value if you insisted, I fancy."

Mr. Bunn nodded.

"Well, that's interesting," he said, affably.

"What is the place worth?" asked Mrs. Fay-Lacy, with a touch of indifference.

"Oh, that depends. Hey, Squire? Depends on a lot of things. But, in the open market, I suppose it ought to be worth—what? Say five thousand pounds."

"Will you sell it for that? I think my friends might give you that for it."

Mr Bunn seemed suddenly to have become dull—very dull.

"Wait a minute," he said, heavily. "I am not sure we want to sell it, hey, Squire?... Might think it over.... Can't see why anybody wants to five there, anyway. Suits us two old fogeys for a week-end, now and then, but it's a dull place, Purdston. Nothing doing there at all. This new neighbour of ours, Miss—Miss—Whatsname—might liven things up a little. She's just bought a big place close by—Harchester Hall, Lord Duless's estate—and I understand she's a niece and heiress of old Whitney D. Vandermonde—America's next-best to John D. Rockefeller. Your friend anything to do with this lady, my dear?"

Behind a thin haze of smoke Mr. Bunn's eyes were watching her intently.

"Nothing so plutocratic!" said the fair Esme, with a tiny yawn, dropping her cigarette end into an ash-tray. "They're just quiet folk come home from abroad who want to settle down,"

Mr Bunn's lip twitched. He had caught the slight dilation of the wonderful eyes of the lady as he spoke.

"Oh, are they? I see. Well, we'll think it over—hey, Squire?—and let you know. Might be able to do business. I don't know that the place is much use to us, and we should like to oblige a friend of yours. We'll think it over and get in touch with you."

"Thanks."

Mrs. Fay-Lacy rose.

"I am meeting them in half an-hour. They'll be so pleased," she gushed.

"That's good. But they may not get it," Mr. Bunn warned her. "Tell 'em that—before they're too pleased."

It was the neighbourly thing to warn her—for neither of the partners had the remotest intention of selling Purdston Old Place, as their little "cyclone cellar" (to quote Fortworth) was called.

And if an ordinary, everyday person had inquired about it he, or she, would certainly have received an ordinary, every-day "no" for answer.

But as Mr. Bunn shortly afterwards expressed it—" when a fancy-witted finch like Esme Fay-Lacy pulls that fairy-godmother stuff on you to the tune of five thousand, you want to hunt for reasons before you accept any offer or you might find yourself nicely in a fairy cart!" He was not far wrong.

And to leave the matter wide open presumably was one of his ways of hunting for reasons.

SHORTLY after dinner that evening, the partners, each comfortably buried alive in a colossal easy chair, engaged in philosophic reflection upon things in general, were disturbed abruptly by the ringing of the telephone bell.

Mr. Bunn, nearest to the noise, lifted the receiver.

He spoke for a few moments, then hung up thoughtfully.

"And who might that noisy, bell-ringing night-hawk have been?" demanded Fortworth, a little sourly. Mr. Bunn chuckled.

"Our fairy godmother again. She rang up to say her friend is on the way to have a little chat with us about buying Purdston Old Place."

"Ah, is he so? Well, he's wasting his time."

"Sure, sure," replied Mr. Bunn. "But he mayn't be wasting ours."

He selected a cigar and took up a tropical position on the hearth-rug.

"You know me, Squire, and you know my gifts," he continued blandly. "I won't dwell on my gift for clairaudience—

Fortworth sat up suddenly. His partner's proneness to self-complacence invariably acted as a red rag to him.

"Clair-which?" he demanded.

"Clear hearing, that means. My gift for hearing things that the average ivory-head never hears—such as the rustle of a flock of bank notes flying towards us a long way off 1 I hear it now. You don't, because you haven't got any remarkable gift. But that's not your fault—it's your misfortune. I'm clairaudient—clear hearing. You're thick-hearing. That's all. No mystery about it. It's the way we are."

Fortworth jerked impatiently.

"Then again there's my gift for noticing details—little minute things that ain't visible to an ordinary man, like yourself—"

"What have you noticed about this Purdston Old Place business that I've missed, anyway?" snapped Fortworth.

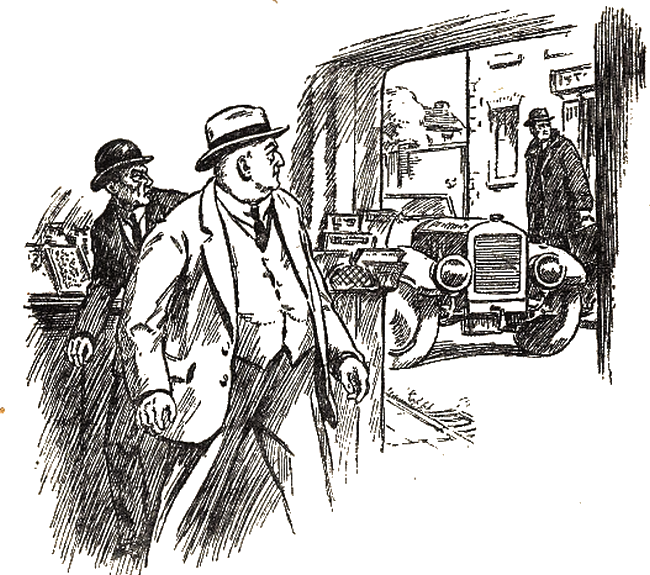

"I'll tell you—" began Mr. Bunn. But he did not, for at that moment Sing Song stole in to announce a caller. He tendered a card to his proprietor.

"Major Aldebaran Weir, Army of the Republic of South China," read Mr. Bunn quietly. "With no address and no club. No place to go to, evidently—so he comes here, to buy us out of house and home."

He glanced at his partner, who shrugged acquiescence.

"Major Aldebaran Weir, hey?" said Mr. Bunn, musingly. "Of the South Chinese Army, as you may say!" He went across to the window, moved the blind a little and peered out.

"Major Aldebaran Weir—with a private Daimler limousine, and a pal in evening dress waiting for him—having a chat with the chauffeur, in fact. Humph! Well, well, show the Major in, Sing, show him in."

He turned to Fortworth.

"I can hear 'em rustling like a flock of starlings," he said, cryptically.

But if he referred, as Fortworth understood him to do, to bank notes, it was soon made evident that they were not notes belonging to Major Aldebaran Weir.

One glance at the thin, yellowish face of their visitor satisfied Fortworth that whatever his personal weaknesses were, slovenly carelessness with his money was not one of them. Dressed perfectly, well groomed and barbered, though he was, nothing could conceal the staring fact that here was a hard man who had lived a hard life.

Lean almost to emaciation, he was something over six feet tall, and in spite of his fleshless appearance he gave off a curious impression of great physical strength. His face was extraordinarily wrinkled, covered with a network of lines, so fine that they would not be visible a yard away. His lips were thin and hard under the narrow line of a queer, drooping, stringy black moustache—so slender that it looked almost like a tapering cord hanging down on each side of his cruel mouth. His hair, too was sleek and straight and black.

But the most startling of the several little peculiarities which one noted instantly about Major Aldebaran Weir, of the South China Army, were his eyes. They slanted like those of a Mongol, and the upper lid was folded over in a straight-seeming fine, so that he had the appearance of a man extraordinarily fatigued, worn-out. Yet it was not this strange, discomforting and, they were to learn before long, deceptive air of deadly weariness which jarred on them most—it was the colour of the eyes that burned under the folded lids.

They were yellow—like darkly brilliant topaz—hot, glowing, luminous, fierce and strange....

"Good evening, gentlemen. I must ask your pardon for this late call, but the matter is urgent," said Major Aldebaran Weir, in a very soft, but also very distinct voice.

Mr. Bunn nodded. Like Fortworth, he had been conscious of an acute thrill of uneasiness on his first glance at their caller, but it had passed. Smiler Bunn had never been a man who allowed another personality to overwhelm his own for more than a second or so—unless he wished it to appear so.

"Urgent, hey? Well, Major, my experience with urgent matters is that the sooner they are settled the better. So sit down, and have a cigar and a whisky and soda, and we'll take a look at the matter," he invited, cordially.

"Thank you. Our charming mutual friend, Mrs. Fay-Lacy, did not exaggerate when she warned me—playfully—against your hospitality."

Their caller dropped into a chair, slewing it smoothly, so that he faced them both.

Mr. Bunn chuckled as he touched the bell.

"If it is hospitable to offer what we regard as the necessities of life to a visitor, then we've certainly got the habit of hospitality. Just bring in some fresh glasses and some more soda, my son," he added to Sing Song.

The Chink's beady eyes flickered to the table on which stood the recently filled glasses of the partners, and he vanished, soft-footed as a yellow ghost.

"I trust, gentlemen, that Mrs. Fay-Lacy was not too optimistic when she hinted that the purchase of Purdston Old Place was largely a question of price?" said Major Aldebaran Weir, in his soft, faintly sibilant voice.

Mr. Bunn pondered for a moment.

"If she hinted that, Major, she was not in a pessimistic mood, anyway. We left it open, true—but no more than half-an-inch open," he explained. "However, there's nothing like talking things over. You want a place in a hurry, and I suppose you've seen it—from the outside, anyway. How much is it worth to you?... Ah, here we are. This will help us talk it over."

Sing Song put down a small tray containing a glass and a siphon on a little table by the caller's arm, and faded into the background.

Mr. Bunn passed the decanter and Major Aldebaran Weir poured himself what must have been a South Chinese officer's ration—about three generous inches. He sprayed half-an-inch of bubbles into it and raised his glass.

"To a successful transaction, gentlemen," he said, with a thin smile, and drained the glass like a man who has drained many a glass before.

He put it on the table and leaned back, with a curious low sigh.

"Well, how much is the place worth to you?" said Smiler, easily. "We'll be frank and tell you at once that we don't really want or expect to sell it at all.

Still, business is always business and—there's no harm in pricing a place. So—to come to business—what do you say?—"

But Major Aldebaran Weir said nothing—nothing at all.

He was sitting comfortably in his chair, his head resting against the softly upholstered back, staring straight at Mr. Bunn.

But his eerie yellow eyes were like dull glass, and his heavy jaw hung down.

For an instant Mr. Bunn stared in amazement, then sprang up.

"My God, the man's dead!" he said, harshly.

"What—what's that?" croaked Fortworth swinging heavily up from his chair. "Dead—dead, man—don't—"

But as they stooped over the lax, lolling form, Sing Song the Chink emerged like a soft, cat-like thing from the shadows in the far corner of the room by the door. He purred to them.

"Not dead, you savvy, master—allee same sleepee—me dluggee him. You seeing—me tellee you bime by—you watchee me, now. He allee same wide awake in ten minute."

He slipped past Mr. Bunn and slid questing, yellow hands into the pockets of Major Aldebaran Weir.

Fortworth, with an oath, put a hand to the shoulder of the Chinese valet to jerk him back from the unconscious man, but his partner stopped him.

"Easy, Squire, easy—he's not such a fool as he looks," warned Mr. Bunn, who had a shrewder idea of

Sing Song's wits than his partner. "Let's see what the lad's after."

They were not left long in doubt. Sing Song appeared only too anxious to show whatever he found.

He worked swiftly, deftly, with a strange excitement.

From each side pocket of the dinner jacket, under the thin, smartly cut overcoat, he produced an automatic pistol of medium calibre, showed them to Mr. Bunn, and slipped them back again. His neat, groping fingers played delicately about the narrow waistcoat pocket of the man in the chair—dipping in, to draw out a thin, flat lacquered case of about the size of a lady's visiting card. Handling it with extraordinary care, he pulled off one end which seemed to act as a cover, disclosing the ends of six little slips of dark ivory—rather like ordinary matches flattened out broadly at the end. He gave a curious, cat-like spitting sound as he glared at these, and laid the case gently on the table.

"You no touchee them, master. You touchee, you deadee."

"You no touchee, master—you touchee, you deadee!"

His fingers curled, like things with eyes, to the inside lining of the waistcoat, writhed softly there, found the secret pocket for which they sought, and came out holding a thin roll of what proved to be tough, cream-coloured silky paper, on which were painted in vermilion ink, a series of Chinese characters—totally meaningless to Mr. Bunn.

The Chinaman stared at them for an instant, muttering. Then he carefully rolled the tiny strip, and replaced it.

The partners watched him, fascinated.

"Some workman, Sing," muttered Mr. Bunn, with a sort of dazed pride.

The Chinaman seized the long, fleshless hand of Major Aldebaran Weir, raised it and slid back the right cuff and sleeve, peering at the inner forearm, murmuring to himself.

Suddenly he stiffened

"Look, master—you seeing, please!"

His finger tip rested lightly on the soft white skin at the inner bend of the elbow.

Craning over, the partners saw a curious blue mark, a design like a little blue tangle of veins.

But it was not the tracery of any veins. It was a tattoo mark—a snake—a cobra with inflated hood.

Sing Song pulled down the sleeve and turned, grinning with excitement, to his owner, drawing up his own sleeve.

"Allee same Cobra Tong, master," he said in a low, rapid voice and pointed to a similar tattoo mark inside his own right forearm. He turned back to the table.

"You no touchee, master—me tellee in one minute," he said, took up the little lacquer case and hurried out of the room. The partners stared at each other and at the unconscious man.

"He's some conjurer, that yellow scoundrel of mine," said Mr. Bunn, with a species of affection in his voice. "Better do as he suggests. We'll get the reasons out of him later. Must be some reason for all this, hey?" He scowled at Major Aldebaran Weir. "This sportsman don't exactly go about unarmed," he observed. "Shouldn't be surprised if he's safer as he is."

Fortworth, always inclined to heavy anger when he encountered anything he did not understand—like a rhinoceros—agreed rather sulkily.

"You'd think he meant to shoot our agreement to . sell the Old Place out of us, the way he comes with a battery concealed on him. We'll have to ask him about that when he wakes. What sort of manners or etiquette is it to come into a peaceful flat with a tool in each pocket this way—Chinese?" he growled.

But then Sing Song glided in. He worked swiftly. He replaced the lacquer-case in the Major's pocket, substituted another glass—half-filled with whisky and soda—for the drugged glass from which the man had drunk—and turning to Mr. Bunn and his partner, asked them to be seated as they were before the drug took effect. Hurriedly, in his clipped, queer English, he explained that if they went on with the conversation at precisely the point at which it had been broken off, the extremely well-armed victim of the drug would hardly realize that there had been any hiatus at all.

Mr. Bunn understood.

"All right, my son.... But I shall be wanting a talk with you afterwards. Who the devil gave you leave to keep valuable drugs like this without my knowledge, hey? ... All right, get out, if you want to."

They sat again, as the Chink disappeared, facing the Major.

His hand moved slightly—a faint stirring—and Mr. Bunn, who had long ago learned that he could trust his yellow valet—if nobody else could—in any serious matter, followed Sing Song's advice implicitly

At the first movement, therefore, of the lean, clawlike hand, he began to speak.

"—the fact is, Major, that we have grown to like the place and nothing but a very exceptional offer would jolt us, so to put it, into parting—a point which, perhaps, we should have put more plainly to Mrs. Fay-Lacy when she first raised the thing in the Astoritz at lunch-time to-day and—" his voice went droning on and on as he watched the light of returning reason rekindle itself in the topaz eyes of the Mongol-visaged Major—" did her utmost to persuade us to part with the place. But, as I say—and my partner agrees with me—it is a question whether the price you mention will chime with the price we might feel inclined to accept. So put a figure to it, Major, put a figure to it—"

The Major had recovered completely now. He said nothing for a moment—but they saw his fierce eyes flash round the room, play over them, dart to the half-empty glass by his side, and his hands steal to his pockets, feeling furtively. He reassured himself of his weapons, and the puzzled suspicion slowly cleared.

"I—pardon me, gentlemen—I have been inattentive. For a moment I could see nothing—a kind of blackness passed over my eyes. A damned funny feeling. It passed in an instant—like dropping off to sleep for half-a-second."

Mr. Bunn nodded with bland sympathy and understanding.

"I know, Major. Liver—get it myself. Sick sort of absent feeling—you kind of lose the thread of what you're saying—and get sort of—well, buffaloed.

Spots in front of your eyes—that kind of thing. As I say, liver. It cost me a handful of money to find that out. I went straight to an oculist and a specialist when I first had that happen to me. Your liver went back on you—short circuited, hey? Try a glass of old brandy for it. Nothing like a drop of brandy for keeping your works up to the mark. No? Well, as you wish... You're feeling all right now? Right. Good. Now what about the house?—"

He leaned back good-humouredly upon their visitor.

"I will give you five thousand pounds for the house," said Major Aldebaran Weir.

Mr. Bunn smiled.

"There is nothing whatsoever doing at the figure," he said. "I'm sorry, Major—but only a fancy price can tempt us."

The Major studied him in silence for a moment. It was completely evident that Mr. Bunn spoke the barest truth and the Major wasted no time.

"I see. You don't really want to sell at all. So I will tell you my outside figure at once. I will give you fifteen thousand pounds for the house," he said, coldly, passionlessly, with nothing whatever in his look or tone to indicate that there was anything extraordinary in this huge jump of ten thousand pounds above the market value of the house.

"It is a pleasure to do business with a man like you, Major," said Mr. Bunn, warmly. "I hate a haggler. The offer is not excepted."

The fleshless yellow face darkened.

"Eh? Refused! My dear sir! I am offering you ten thousand pounds more than its value 1"

"Yes—that's why we're refusing it, Major," said Mr. Bunn, very cheerfully indeed. "If it's worth fifteen thousand to you we kind of feel it's worth more than that to us—as soon as we can find out why it's worth that money to you."

Major Aldebaran Weir said nothing for a moment His eyes burned yellow, but he kept perfect control of himself as he rose.

"You have wasted my time," he said, with a curious, cold hostility in his tone.

"No, no, Major—you've wasted your own time," corrected Mr. Bunn, easily.

Major Aldebaran Weir nodded after a moment.

"I agree. I was misled by the confidence of Mrs. Fay-Lacy," he said softly. He put on his hat and his gloves. One hand he slipped into a pocket of his dinner jacket.

"I advise—I strongly advise—that you sell the house to me," he said, with a faint, far-off menace in his voice. "It will save me a great deal of trouble."

"You're angry, Major. What trouble will it save you?" smiled Mr. Bunn.

A sudden dreadful malignance shot into the strange eyes of the man; and his wide, thin lips parted in an ugly smile.

"The trouble of having to negotiate for its purchase from your executors!" he said, slowly.

Mr. Bunn sensed, rather than saw, the outline of the muzzle of the automatic pistol pressing against the cloth of the Major's pocket.

"Executors, hey?" he said. "Well, well, if you feel that you want to take all that trouble, take it I

Certainly. So do, Major Aldebaran Weir of the South Chinese Army, so do! But you may take it from me that it ain't a really original idea. You are not the first enterprising young fellow who has tried to fix things so that our executors come into action—over our dead bodies, so to put it. But we're still here, you notice. My advice to you is to study how to keep out of trouble with us—not to charge headfirst into it."

He moved tranquilly to the door, and opened it.

"You've got a lot to learn about house-hunting," he continued. "Your tactics are too Chinese to please me—and you'll find that unless you can learn to negotiate for a house in this country without dragging in a lot of executors, you are going to remain homeless for a considerable time. It ain't the popular thing to threaten to remove the owner of a house unless he sells it to you, nowadays. At least, not in England. It's out-of-date and old-fashioned. Used to be done, I believe—but it went out of fashion some time during the reign of Stephen and Matilda—whoever Matilda may have been. So, good-night to you, Major Aldebaran Weir—of the South Chinese Army!"

He shouted for Sing Song, who appeared silently, apparently from nowhere, to show the caller out.

The Major hesitated, glaring.

Then he shrugged his shoulders and passed out.

"You shall not be forgotten!" he said, malevolently, as he went.

PROMPTLY the partners put Sing Song through an examination concerning his most unvaletlike behaviour in connection with the deadly-looking Weir.

He explained satisfactorily.

Major Aldebaran Weir, it appeared, on seeing that Sing Song was a Chinaman, had made a certain sign. Sing Song had recognised the sign, but he had not answered it, for it had been one of the signals of membership of a certain Chinese Tong, or secret society. Sing Song, many years before, had been a member of this tong—the forbidding name of which, he explained, was, in full, The Honourable Society of The Cobra—but, in his simple Chinese way, little Sing Song had long since learned the inadvisability of allowing any casual stranger to know that he belonged, or had once belonged, to any tong whatsoever. There were obligations attached to membership, and highly discomforting penalties were liable to follow disregard of those obligations—in certain circumstances. That became clearer to the partners later on—though they accepted the Chinaman's word for it from the start.

Aware that this visitor was a member-—and probably an important one—of this, one of the most .powerful of the many criminal societies in China, Sing had not hesitated to use his drug for the purpose of aiding him to get a somewhat clearer notion of Major

Aldebaran Weir's character in general. The pistols explained themselves, but the strip of painted paper explained much more; even though, stated Sing Song, it contained only a few words and three signatures, of which Weir's was probably one. These names meant that three members of the tong were entrusted with a special-enterprise, and, presumably as a guard against treachery, each of the three possessed a copy of the written undertaking signed by the others—a device much in favour among the desperadoes of all tongs.

The words over the signatures Sing Song had not been able to read—they were in some dialect or tongue unfamiliar to Sing, who was far from being an educated Chinaman. But he had made out among the characters two names in English:

"Patricia Charmian Vandermonde" and "Whitney David Vandermonde."

The Chinese signatures had been those of three men, Li Shan, Fan Tzu Kang, and Tsin Tan. One of these names, Sing believed, was the Chinese name of the Major.

The roll of paper had been the only interesting find—that and the discovery of the hall-mark of the tong—the tattooed cobra on the inner arm.

As for the lacquer case, that merely corroborated the evidence of the man's character suggested by the automatics. Sing Song proved this very simply. He produced a lacquered case almost identical with that carried by Major Aldebaran Weir, placed it on a table, warning the partners not to touch it, and disappeared for a moment.

He was back almost at once, bringing a rat in a wire cage.

"You watchee, please master," he advised, and proceeded to manoeuvre the rat—a big, lively, vicious beast—into a corner of the cage. Then, very carefully, he took one of the match-like ivory splinters from the case, and pressed the needle-sharp point against the rat with just enough force to give the merest pinprick. The rat squeaked once, then suddenly relaxed limply, shivered, and lay still.

It was dead. A heavy rifle bullet could not have killed it quicker.

"Poisoned thorns!" said Mr. Bunn, quietly, his ruddy face paling a trifle, his eyes hard and greenish like jade.

Sing Song smiled, carefully replaced the splinter in its case, and explained that when Major Aldebaran Weir felt called upon to use the ivory "thorns" in his case, he would get a disappointment—for he, Sing Song, had substituted for the poison splinters in the Major's case, half-a-dozen precisely similar but harmless one from a case of his own.

A day was to come when Mr. Bunn would appreciate that quick change to the full; and perhaps he had some dim inkling of that, for he actually did then what he had spoken vaguely of doing for years. He raised Sing Song's "money" then and there.

"Right, Sing. You can put those poison pins out of action right away—in case of accidents. Understand me, son? At once. And from now on you stand to draw from me five shillings a week rise! D'ye get that, my lad? You're raised. Your money's gone up. Hey? How's that, son? I've talked about it for years—now I've done it. A crown a week! That's the result of sticking to your job, Sing. Raised money. Understand, now, you don't need to play the fool, or get swelled head because your money's gone up—or I'll cut it down again, quick. But you've been a good lad. Keep so. You look after us, and I'll take care of you. Remove the rat—and come back here!—"

From the discussion which followed emerged the definite decision that the interests of the partners clearly and unmistakably called for their presence without loss of time at Purdston Old Place.

"It's simple arithmetic," Mr. Bunn had declared to his partner. "Look at the facts—here, I'll run through 'em, to save time: First, Patricia Vandermonde, sole heiress to the second richest man in the world, decides to spend a year or two in England and buys Harchester Hall.

"Second, Major Aldebaran Weir, as cold and complete a crook as I ever had the privilege of seeing searched, offers us a fancy price for Purdston Old Place, the nearest house to Harchester Hall there is.

"Third, Weir is proved to be a member of this Cobra Tong, a powerful criminal society.

"Fourth, we've found out that he and two more like him, have started out on some enterprise to do with Whitney D. Vandermonde and his heiress, and as those people can't be in need of anything the Cobra crew can give 'em, we'll put it the other way round and say that the Cobra gang are in need of something the Vandermondes can provide—if they want to.

"Fifth, Weir is fool enough to threaten us because we won't sell.

"Sixth, and last—and most important—there's my hunch, my presentiment, that a great flock of notes—enough to darken the sky—have taken wing in our direction.... How about it, Squire? It seems to me that we're wasting our time hanging about in London. Purdston is where we ought to be. Hey?"

Fortworth, who had been grumbling intermittently ever since Major Aldebaran Weir had left, agreed dourly.

"Good!—"

Mr. Bunn glanced at the clock.

"Ten-thirty! There's no time like the present. What's to stop us running down there right away? Money's like a bird. If you're going to drop a pinch of salt on its rudder, you want to be lively about it."

Fortworth had no objection to advance, for, when roused and "started," he was about as easy to stop as an irritated grizzly bear. So Mr. Bunn got what he described as "busy."

"Good! You telephone to Bloom to expect us, Squire!" Bloom was the butler who, with his wife, comprised the "staff" at Purdston.

"You, Sing, clear up here as quick as you can, and then get the car round."

"Yes, master."

Sing hovered, uncertainly, his beady eyes glittering. "Well, what is it, son? Hurry up and out with it."

"Please, master, you takee gun this time, yes?

Velly bad, allee same quick killee evely time—Cobra Tong men bad—velly cunning, velly quick 1—"

Chevaliers d'industrie, knights of fortune, adventurers though they were, it was very rarely indeed that Smiler Bunn and Fortworth ever carried firearms, and never before had the competent Sing ventured to advise it.

But evidently he was taking this business in very grim earnest, and as the partners were no longer sufficiently young and foolish to ignore good advice because it came from a humble source, they agreed readily to go armed.

"Well, you ought to know about the Cobra Tong—as a member yourself," said Mr. Bunn drily. "We'll take our tools along. Now, see about it 1"

Within half-an-hour their big Rolls-Royce limousine was sliding across Westminster Bridge on its way to Purdston.

For a time the partners smoked in silence.

The queer-looking scoundrel who called himself Weir and claimed to be a Major in that nebulous and far-off horde which he described as the Army of South China, had chilled them both a little, either by his appearance, his threat, or, more probably, by the atmosphere of sheer, cold-blooded malignity which, towards the end of his visit, he had radiated. Both 8 Mr. Bunn and his slightly morose partner were vaguely conscious of a premonition that they had been, or were about to be, caught up in an affair, compared with which most of the adventures from which they had profited in the past, were but small and dangerless.

Two facts stood out starkly for their consideration

—the one being that the Tong against which they were preparing to campaign was wealthy, powerful, and formidably unscrupulous, and the other being the practical certainty that any affair involving Whitney Vandermonde and his heiress had to do with very great stakes.

"Any guessing we do now will be just that much good guessing wasted," said Mr. Bunn, as they ran clear of the suburbs and the pace of the big, powerful car increased. "But if you can tell me what is the connection between you and me at Purdston, Patricia Vandermonde at Harchester Hall, Whitney Vandermonde in New York, Mrs. Fay-Lacy in London, Major Aldebaran Weir of the South Chinese Army, and these Cobra Tong devils from nowhere, you'd tell me something I can't guess for myself."

"I am no guess-expert," said Fortworth, dourly. "But there's one thing I can point out which is no guess. You can take it that if Weir carried these poison thorns as part of his stock-in-trade, his two Chinese pals carry 'em too—and theirs haven't been unloaded by Sing Song. You want to keep that glued in your mind!"

He stared sulkily out of the window.

"And I'll go so far as to say that I'm not fancying the business of clashing with these highbinders, at all. We're butting in between a multi-millionaire, of whom we know nothing, and a crew that would be better left alone. I hope your hunch is a real hunch, and one that's going to bring in a whole lot of grist to the mill, for I've got more than a mere hunch that we're going to earn it. Personally speaking, I'll go so far as to say that I wouldn't have agreed to touch the thing if that other thing out of the Chinese Army hadn't threatened us."

His voice thickened, and Mr. Bunn concealed a smile.

"1 allow no man, whether of the Chinese Army or the Salvation Army or any other Army, to threaten me in my own flat," went on the ex-peer, who seemed to have been steadily accumulating a grim, slightly ferocious determination to teach Major Aldebaran Weir a lesson that he would not readily forget.

That was Fortworth's way, and nobody knew better than the astute old adventurer his partner.

"I think we are damned fools to interfere, and I don't value your hunch a cent, to be frank about it; but I've been turning things over in my mind, and I guess I'll have to have another word with that Aldebaran tough," growled Fortworth.

"Sure, Squire," agreed Mr. Bunn; "and you're right. Besides, they tell me that this little lady, Patricia, is a very friendly, attractive little dame."

His voice changed:

"Better keep your gatling handy," he warned. "I shouldn't be surprised if these Cobra guys start the rough stuff—if any—without much delay. What's Sing doing?"

Sing Song had switched off all his lights, and the pace of the car slackened as it swung round a sharp right-hand turning.

They were approaching their house, and from the road on which they were travelling now a lighted car would be easily visible from the house.

But rather unexpectedly Sing Song stopped the car, and came round to them.

"Well, you yellow wolf, what is it?"

Sing explained that he had seen a light—near the house. Nothing more than the tiny beam of a small electric torch, which had flashed out, wavered and vanished.

He had stopped the car, he said urgently in the darkness, because he thought perhaps his master would prefer to approach the house quietly and on foot. Mr. Bunn peered out towards the house.

"No lights indoors, either," he muttered. "That's not usual; you telephoned Bloom that we should be coming, didn't you, Sing? And he answered, hey?... Well, what the devil has he got the place in darkness for? Ought to be busy laying the table in the dining-room at least. I don't like it, Sing, you yellow scoundrel.... He's right, Squire. We'll leave the car here and walk up to the house. Probably it's all right, but may as well be careful!—"

They moved quietly through the darkness towards the gate of the curving, tree-bordered drive leading to the front of the house.

It was very dark.

At the drive-entrance they paused, listening. From the edge of the village, some considerable distance away, hidden by a rise, they heard a dog howling faintly, but save for that, there was no sound. Away across a wide park, the boundary of which was also the boundary of the Old Place grounds, many lights still burned warmly in the windows of Harchester Hall. But the house of the partners was dark.

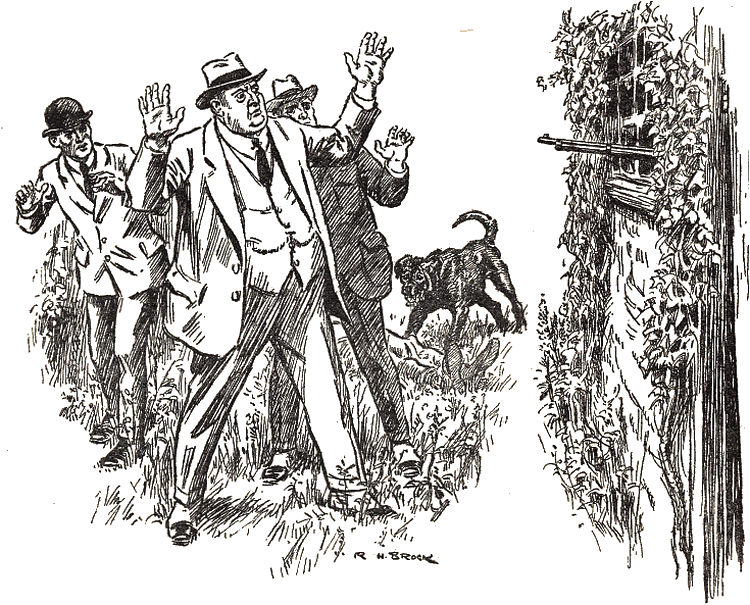

"Seems all right—queer about the lights, though," muttered Mr. Bunn. "All right—go quietly." He led them down the drive, a big electric torch in one hand, and automatic in the other. They moved silently on the short turf at the side of the roadway.

They had gone a third of the way along the drive, and Mr. Bunn was beginning to smile at their caution, when a wild thudding of hoofs on the hard gravel at the front of the house drummed suddenly through the darkness. There was a shout, a thin scream, and the dance of the hoofs settled into the steady pounding of a gallop.

"Stand back!" warned Mr. Bunn.

The flying hoofs drummed near, and drew level. The sudden beam of Mr. Bunn's torch threw up a picture of a horse galloping furiously through the darkness towards the drive gates.

Crouching low over the flying animal's neck was a man. They only saw his face for the fraction of an instant, white in the electric ray. It was the face of a stranger.

"Man's mad—he'd have broken his neck if we had shut the gate,", said Mr. Bunn. "What's he doing here, anyway? Are there any more like him left?—"

He switched off his ray. Even as he did so the whirring rush of a motor suddenly started came soughing through the darkness to them, and almost immediately a dazzling blaze of lights poured down the roadway as the driver of the oncoming car switched on.

Roaring up his engine furiously and changing gear with extraordinary speed and skill, the driver of the car was travelling dangerously fast in the narrow drive by the time he swung past the trio on the turf border. The ray of Mr. Bunn's torch was lost in the blaze from the big, powerful headlights. As the car swung past, there was just enough light to catch a glimpse of the faces of the men that were peering over the side of the car—dreadful, mask-like, yellow faces, two with black, beady, glittering eyes, one with curious, eerie eyes that, for the fraction of a second, flared with a greenish-yellow flame in the ray from the torch.

They were gone in an instant. But though two of those evil, Mongolian, oblique-eyed faces were strange, the watchers recognised the third.

It was that of Major Aldebaran Weir.

"See that," said Mr. Bunn sharply. "They've lost no time! Must have come on almost immediately he left us. Come on—let's get to the house and see what has been going on!"

They hurried down the drive, and came out on the open, gravelled space before the front door.

Mr. Bunn ran his ray over the front of the silent, lightless house, and suddenly he swore, harshly, stiffening like a pointer.

"Too late, by Heaven!—"

Under one of the ground-floor windows lay the body of a woman.

IN his excitement Mr. Bunn had jumped rather wildly to the conclusion that the dark figure lying prone under the wall of the house was that of Miss Vandermonde, but as he knelt by the side of the unconscious woman flashing the ray of his electric torch on her white face he saw that it was Mrs. Bloom, the wife of their butler at Purdston Old Place.

As Fortworth joined his partner, she opened her eyes, staring up with an expression of terror.

Sing Song had disappeared, prowling round the house.

"Hello, Mrs. Bloom, what's all the trouble?" said Mr. Bunn, slipping his arm round the shoulders of the housekeeper, helping her to sit up. "I don't like seeing you this way—don't care about it at all. Easy now—don't hurry—easy, I say." He steadied the fluttering hands and spoke sharply to quell the symptoms of rising hysteria which the woman showed.

"Nobody's going to be allowed to hurt you, I tell you. Be easy. Hey? Are they gone? Sure, they're gone. What's that? Want to get up? Sure, you shall."

He raised her and holding her arm tightly, stared into the darkness of the garden and shrubberies, shivering, her eyes still a little wild.

"I—I fell from the window—" she gasped, looking up. Mr. Bunn flashed a ray upward and saw that one of the first-floor windows yawned open.

"I was tidying your room, sir, and I thought I heard my husband shout' Help!' I listened a moment but he did not shout again. I turned to the door to go out and call downstairs to Bloom and—and there were two Chinamen. They had pistols. Somehow, it gave me a shock—although I'm used to surprises here with you gentlemen—and I rushed to the open window. I—must have fallen. And I thought I fell against a horse—I seem to remember a sound of hoofs and a man swearing before I struck my head on the ground. Where is Bloom, sir?—"

She had been speaking hurriedly as the partners took her into the hall and made her sit down. Whatever they may have been in their dealings with men neither Mr. Bunn nor his partner could ever be otherwise than gentle and generous with any woman.

"Bloom? Oh, he's all right, no doubt. Capable card. Bloom. Here, you take a drink of this,"—Mr. Bunn passed her his flask-cup, half full of his sovereign remedy—rare old brandy—" and just sit here for a minute while I see where he is."

Switching on every light he approached, Mr. Bunn passed quickly out of the hall towards the kitchen. He was back almost at once.

"Nothing there," he said and went into the dining-room. He had no farther to go.

The butler was there, lying in a crumpled heap on the floor, surrounded with an assortment of silver and cutlery fallen from the overturned basket by his side.

Evidently he had been laying the table in readiness for the partners' arrival, when he had been attacked. Mr. Bunn bent over him, as Mrs. Bloom came in.

"They've killed him!" she said shrilly, but Mr. Bunn, his hands busy over the butler, laughed a little harshly.

"Sandbagged him! He's not dead! Probably be all right before long," he said.

They raised the unconscious man to the couch.

"Give him some brandy, Squire," commanded Mr. Bunn. "Where the devil is Sing Song?—"

He raised his voice.

"Hey, Sing!"

"Master!" The Chink, his eyes glittering, slid soundlessly in, promptly on time as ever.

"Well, son, found anything? What were they after, anyway? Couldn't steal the house... hey? Come with you? You 'showee' something. All right."

They left the butler in the care of his wife and, with their pistols carefully ready, followed Sing Song out into the dark. He led them quickly down the drive, through the entrance gates and into the road. Just before they reached the spot where they had left the car the Chink halted, pointing to a dark mass at the side of the roadway. He moved past it, stepped to the car, switched on the headlamps, flooding the roadway with light and came back to the partners who were staring at the object revealed.

It was a dead horse—saddled and bridled for riding.

The three craned over the animal, examining it.

"Now, whose horse is that? And why did its owner bring it for a gallop in our drive at midnight before killing it—and if he killed it himself?" demanded Mr. Bunn.

"And why kill a horse of the class of this one, anyway?" added his partner. "It's mighty near a thoroughbred. Very high-class hunter or steeplechaser."

Fortworth was right. The poor beast had been an unusually high-class animal—a bright red bay, powerful and shapely, about five years old. Less than a quarter of an hour ago they had seen this horse galloping—apparently strong and vigorous.

But now it lay, sprawled and shapeless and already oddly stiff. Its muzzle was covered with a strange greenish foam, blood-streaked and still moist.

Sing Song muttered something to himself. He knelt down and ran the big torch he had taken from the car, over the carcase, stooping low, searching and peering like a man who looks for some particular thing which he expects to find.

He found it quickly enough and stared up over his shoulder at Mr. Bunn.

"Master, you seeing—" he said softly and pointed to the horse's neck. They craned over.

Deeply embedded, low down, near the throat, they saw the flattish base of one of those needle-pointed ivory thorns.

Carefully, Sing withdrew it.

"Now, how the devil did those Chinese man-eaters shoot that thing into the horse?" asked Mr. Bunn, "through a blowpipe or how?—"

Sing Song grinned wryly.

"Me showee—you watchee. Velly easy."

He balanced the reddened splinter on the inside edge of the first and second fingers of his right hand, so that its point protruded perhaps an inch beyond the finger, and the flattened base rested against his thumb-nail, which he strained against the side of his second finger, then, half turning his wrist in a peculiar movement, he shot his thumb forward in a way that was vaguely like that of a boy shooting a marble—and the thorn darted forward to bury itself for two-thirds of its length in the neck of the horse. It pierced the tough skin with appalling ease.

"Huh! There's a devil trick, if you like," grunted Mr. Bunn. "How d'you do it, Sing?"

The Chink's grin widened.

"Allee same plactise long time—five year ten year. Onlee Cobra Tong men plactise this killee. Me showing you bimeby, master," he promised.

"And how far off have you got to be to be out of range—to be safe in fact?" pursued Mr. Bunn.

"Twainty feet—thirty—plaps forty feet. Plaps be wise you forty feet—but he hit you evely time he flickee twainty feet off. If he hit you and thorn stickee you deadee, master—allee same deadee like horse."

"Yes, damn you, I understand the deadee part of it, my son. No need to rub that in... unload that thorn before it does any more damage."

Mr. Bunn spoke thoughtfully.

"What's it all about, anyway?" he asked his partner. "I don't get the idea at all. Who was the rider of that horse and what was he doing here at our place? And what was that yellow-eyed rattlesnake out of the South Chinese Army—if any—Major Aldebaran Weir, and his pals doing here for that matter? It wasn't our names on that slip of paper, was it? Whitney and Patricia Vandermonde were the names. I don't like it. It's a mystery, dark and damned dangerous. If this Cobra Tong has a grievance against Whitney Vandermonde how does it help 'em to sandbag our butler? Bloom ain't exactly a friend of the Vandermondes, and is never likely to be... what does that Tartar-faced tough want this house for, too?" He turned suddenly.

"This has got to be thought out—and quick!" His eye caught the horse.

"No need to leave that here—inviting inquiries. We don't want a crowd of police prowling about trying to solve the mystery of the Dead Horse... we'll attend to the animal ourselves."

They did so. Laboriously, they managed to drag the stiff carcase into their own grounds and there, in a dark and secluded comer, they left it until next day, when, after another examination, they purposed bestowing upon Sing Song and Bloom the privilege of burying it.

Then Sing brought in the car, and they went indoors to continue their investigations.

Bloom, a little shaky, was sufficiently recovered to talk. His story was told in half a dozen sentences. He was laying the table when he heard a noise at the door, looked up and found himself confronting a tall, lean man with strange yellow eyes and two Chinamen.

They were all moving into the room and the tall man was covering him with an automatic. But before he had time to speak the Chinamen, moving with extraordinary quickness, had rushed on him one from each side. He had shouted "Help," and suddenly had been beaten into the silence and blackness of insensibility by two stunning blows. The next thing he remembered was his master, Fortworth, bending over him and giving him brandy.

Mr. Bunn listened in silence to the end, then nodded in a dissatisfied sort of way..

"Well, that tells us very little," he commented. "Just as well for you, Bloom, they knocked you out before you could put up a fight. They aren't the sort of folk who stick at trifles. Did they say anything before they rushed you?"

"Not a word, sir. They came in as if they expected to see me and they knocked me out as if they had it all cut and dried hours before."

Mr. Bunn nodded.

"Yes, they're a far-sighted crowd, Bloom," he said. "Have you missed anything?"

"Not yet," replied Bloom.

"You never heard anything of the man on the horse?—"

"No, sir ... I noticed nothing out of the ordinary all the evening—oh, except, now I come to think of it, the dog. He barked a bit just after I came into the dining-room. But he stopped almost at once and I remember thinking that it must have been a stray cat that started him off."

"Ah, all right—you and your wife had better turn in and have a good night's rest,'" said Mr. Bunn. "It's late and you've both had a rough evening. Help yourself to a drink, Bloom, and turn in. That'll be the programme for you."

Bloom, nothing loth, made haste to obey. He disposed of a shaken man's portion of Scotch whisky—about three inches—and disappeared.

Mr. Bunn reached for the hat he had only just laid aside.

"No, not going far," he said in response to his partner's unspoken query. "But I just want to see why old Corporal stopped barking—though I fancy I know. It's an easy guess."

With that faithful shadow, Sing Song, at his heels, he stepped through the French window and made his way round to the kennel which was the abode of the big, black, queer-tempered, cross-bred hound they kept at Purdston.

He was an ugly customer to strangers, this heavily built mixture of boar-hound, blood-hound and Airedale, which Mr. Bunn, fascinated by his air of truculence, had picked up as an overgrown puppy in a gipsy camp some three years before.

"Don't understand why old Corporal wasn't making some very rough music when we came up, Sing," muttered Mr. Bunn, as he crossed the yard at the back of the house. "I guess they've left a thorn in him, too."

But he was wrong. "They" had not wasted a "thorn" on Corporal.

Mr. Bunn and Sing Song came upon him, lying gaunt and angular, outside his kennel.

"As I thought—he's dead, hey, Sing?—"

But Sing laughed sibilantly in the shadows.

"No, master—you lookee, him sandbagged allee same Bloom. Tong-men not knowing him here—no time killee. Look, master."

He disentangled a big shred of cloth from the great jaws of the dog and passed it to Mr. Bunn.

"Ah, that's from Weir's overcoat," said Mr. Bunn. "Good old Corporal. They overlooked him probably, and he burst out on them as they were prowling round the house. They beat him down and let it go at that. Pressed for time, hey?... Thought he was an ordinary dog, hey, Sing? That's the first bit of luck this evening, boy. Bring him in and look after him. If we can get him right before the scent gets stale I guess it won't be long before we get a claw driven into the identity of mysterious Mr. Horserider. Here's where old Corporal is going to pay off his board bill, hey, Sing? Damn you, Sing Song, I'm very pleased about this—very pleased indeed."

And so saying Mr. Bunn hurried indoors to celebrate his pleasure in his customary thirsty fashion. Certainly, as far as the curiously bred Corporal was concerned, he had reason to be pleased—for like many other creatures, human variety and otherwise, what Corporal lacked in beauty he amply made up for in usefulness. He had powers of scent which equalled those of a bloodhound, and Mr. Bunn claimed that Corporal could follow any trail to the end.

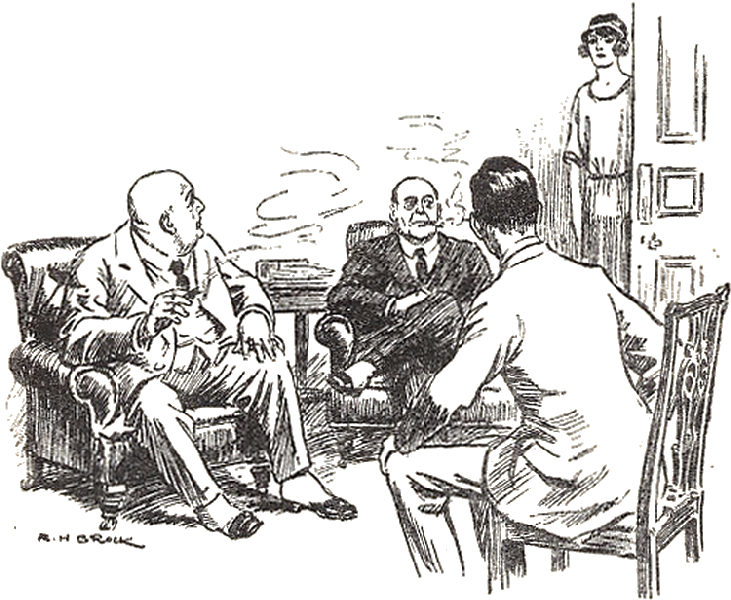

"I THINK it's about time we had a little straight talk," Mr. Bunn was saying, perhaps an hour later, when having returned from a close inspection of the interior of Purdston Old Place, and its window, door, shutter and other fastenings, he settled down in a mighty armchair facing his partner across a small table comfortably munitioned with decanters and such aids to inspiration. "So now for a little algebra. Sing, my son, stand over there where I can sec you. You may have a drink. On the whole you've earned it."

His face was dark and dissatisfied—but not so thunderous as that of Fortworth—as he poured himself what he termed a "lifebuoy."

"Don't interrupt me while I'm talking, if you don't mind, either of you. We're in a nasty, dangerous business and I don't like it. But there's money in it, and man cannot live by bread alone, as Shakespeare puts it—or was it Charles Dickens?—one of 'em, any way. The way I read things is that this Weir wolf and his crew are up against the Vandermondes—probably old Whitney Vandermonde, for I don't see how a girl or a harmless woman could have hurt a Chinese Tong at all. But Whit—for short—is in America, so we'll say that these Chinese brothers of yours, Sing Song, under command of the Major, are aiming to injure

Whit, through his daughter. Either—for a guess—they mean to kill her or, more likely, kidnap her. But that's only a guess, and we'll have to investigate it later." ... He paused to readjust the level of the contents of his glass.

"We shall have to stop their game for the sake of the girl and the gratitude of Whitney Vandermonde. It should work out at five figures, I estimate, though it's an early estimate, and gratitude ain't easy to put into figures at the best of times. For some reason—probably because it's the nearest house to Harchester Hall—Weir & Co. want this house. Want it as headquarters, no doubt. That's the only reason I can see. But what I don't see is why they come here behind our backs and beat the senses out of Bloom. We'd refused to sell 'em the house—and that settled it. Why batter Bloom? There's neither rhyme nor reason to it, you'd think. But unless I miss my guess by furlongs this he-wolf Weir doesn't do things without a reason. When we find the rider of that horse no doubt we shall be on our way. First thing, therefore, is to find that rider. We'll do that to-morrow with luck, and provided old Corporal can smell as well as usual."

He finished his glass.

"Also we must make the acquaintance of this Miss Vandermonde. Shall have to arrange that—pay a friendly call there to-morrow, and get acquainted."

Fortworth snorted slightly, and Mr. Bunn cocked an angry eye at him.

"Well? Any objection?—"

"I don't suppose Miss Vandermonde will be any too grateful for our acquaintance," said Fortworth. "You've got to remember that she is—or will be—one of the wealthiest women in the world, and it ain't very likely that she's exactly short of, or in need of, two more acquaintances. Suppose she turned us down."

"Nobody," responded Mr. Bunn, with dignity, "nobody has the right to turn down two private English gentlemen of means, manners and leisure. Leave the social stuff to me—I understand it.... What I want to see you two revolving your brains round is the fact that Weir & Co. are dangerous, and quick, and deadly—and armed with arms they won't hesitate to use, any more than their little friend the Cobra hesitates to use his fangs when in the mood.... And the chief of this crowd was introduced to us by Esme Fay-Lacy—whom we've known for years—must get into touch with her to-morrow. I've got an idea that she doesn't quite know what kind of a scorpion she's got hold of in this Major Aldebaran Weir—"

He paused for a moment.

"Anybody got anything to say? How about you, Squire? Any ideas?"

But Fortworth was devoid of ideas and hesitated not at all to say so. Lacking data, he observed (though less elegantly), he had arrived at no conclusions.

"Well, you then, Sing Song. Have you told us all you know—or can guess?"

But Sing never answered that straightforward question, for at that moment the huge, gaunt, heavy-jowled hound, sprawling on the hearth at Mr. Bunn's feet, raised his fierce, ugly head, growling low down in his throat. His brown, bloodshot eyes gleamed dully in the light.

They had brought him round, but he had been heavy and dazed for the past hour. Now he had partially recovered.

His corrugated mask seemed to knot itself into a hundred new wrinkles as his lips writhed back from his white fangs, and the stiff hairs on his shoulders and along the line of his backbone stood up like porcupine spines. He raised himself and threw up his head for the deep note—half bay, half bark—he usually sounded, but Mr. Bunn grabbed him swiftly by the throat.

"Quiet, Corp—quiet!" he said softly, menacing the hound with his left fist.

Corporal understood, and was silent.

"Listen!" whispered Mr. Bunn.

The three, companions in many a tense moment, listened tautly.

For a moment they heard nothing.

Then, very low, came the faint sound of footsteps on the gravel path outside moving quietly round the house.... Stealthy steps...

Mr. Bunn flushed an even deeper red, glancing at the clock. Twenty minutes past one!

"They're working round the house," he said softly. "And who the devil is it thinks that they've got a right to come prowling round here at twenty past one at night?—"

He stood up suddenly

"We'll have a look," he whispered angrily. "These Chinks, hey?" he demanded, staring at Sing. But Sing Song shook his head, his eyes glittering.

"No, master. That boot allee same nailee sole—not Chinaman boot. You going, me coming, master—we seeing bimeby him English boot crunchee gravel."

He slid from his chair, and a wicked-looking knife gleamed in his hand, appearing, it seemed, by magic from nowhere.

"Put it up, you!" said Mr. Bunn in a half-snarled whisper. "If that's no Chink outside you can cut out the solo on the knife. Give it here, boy. / will say when knives are called for."

He took the weapon from the reluctant Chink and put it on the high mantelpiece.

"Now make for the French window facing the lawn. He was working round that way. We'll slip the bolt and be ready to fall on him. Quiet, Corp—and stop here. We'll need you to-morrow."

In the morning-room, with its French window, they paused to listen. Almost at once came the faint jar of a nailed shoe or boot on the tiled floor of the little verandah outside the window.

They heard the thin squeak of the handle of the French window as the prowler gently tested it.

"Still! Keep still," breathed Mr. Bunn. "He's coming in. Wait till he's well inside—then rush him. Easy, now."

They sensed and heard rather than saw the slight inward bulge of the window as the prowler put a testing pressure on it at top and bottom to discover whether there were bolts as well as a lock.

There were, and for a few moments the man outside made no further movement audible to the three inside the room. Then a low, steady rasp, very harsh and slow, jarred quietly from the outside.

"He's diamond-cutting a pane," breathed Smiler. "Wait on him—wait on—"

He did not finish, for a sudden, loud jangling jet of sound dinned across the dark silence, muffled in a moment by the deep note of Corporal—who probably was as startled as themselves.

The telephone in the room they had just left was ringing furiously. There was a quick, light clatter of hasty feet on the verandah outside, dying out at once.

"Gone, damn him! He's away like a fox. After him, Sing! Get him, boy."

The Chink shot across the room, snatching at the key and bolts of the French window. But the bolts normally unused, were stiff and delayed him badly.

Mr. Bunn and his partner were at the telephone long before Sing Song was out of the house...

"Hello!" snarled Smiler, most uncordially. "Hello! who's that—ringing up at this ungodly time o' night. Hey? Oh, you, is it, Esme? You ought to be in bed—hey?—hello—yes, tucked up in bed, I say. What's that? Hello? Are you there?... It's Mrs. Fay-Lacy, very excited," he said in an aside to his partner. "Hello! What is it? Are you there?—can't hear a word you say. There's some guy cross-talking into the machine, Squire, like a d—d ghost calling out of a coal-mine somewhere—hey, you there, what's that?—Charmian Vandermonde doesn't guess that Fan Tzu Kang and his men are—what—what? Are you there? Hello! Are you—where the h 1 are you—who are you?—what's that? Oh, you again, Esme, is it? There was a guy cross-talking about Sam Sue Kang—what's that? You're sorry-sorry, yes, I've got that—sorry Major Aldebaran Weir isn't the person you thought he was—your friend is another man altogether—what's that?—muddle? Mix-up? No idea who he is ... All right—all right, Esme. I understand. No—no harm ... Eh? Explain later. Sure, Esme. Lunch with me one day, go into things. Knew you were too much my style to put me on to a crook like Weir—oh, sure, sure—yes—good-night—time you were in bed—yes,—certainly—tucked up in your little white bed—and switching off your pretty pink electric light—not pink—yellow—ha-ha—well, well—good-night!—"

He hung up and turned to his partner.

"That was Esme Fay-Lacy—only an excited maniac kept butting in. She rang up to warn us that she's discovered that Major Aldebaran Weir ain't the particular friend from abroad that was recommended to her. Some mistake about letters of introduction. She had just found out and as she fancied Weir was a bad lot she thought she couldn't do less than warn us.... But I was more interested in that other guy who was trying to talk about Patricia Charmian and Tam Sue Kang—eh, well, Fan Tzu Kang, then—but I couldn't get any sense out of him. He had a touch of an American accent, I thought, and he must have meant Miss Vandermonde, anyway. It looks as if Fan Tzu Kang is this Major Weir—this mysterious guy spoke of him and 'his men.'... Now, what about that creeping Joseph we sent Sing after? We'd better see—"

They turned back to the morning-room, only to meet Sing Song coming in ruefully.

"Me solly, master. Him gone too far allee same too quick. Me no seeing, no catchee." His eyes gleamed as he held up a tweed cap.

"But can do, master. Findee cappee—Golpril smellee him. Please, you coming quick!"

He handed the cap—an ordinary grey cloth affair—to Mr. Bunn.

He took it, glancing rather sourly at the clock.

"Creeping on towards two a.m.," he said. "And you, you thundering mixture of wire and whipcord, want us to go chasing over hill and dale after the owner of this cap, with a poor devil of a hound who probably has had his sense of smell battered clean out of his body for the next twenty-four hours. However—" he turned the cap over, scrutinising it carefully—"no name, no trade-mark, huh!—however, we'd better follow it up, if we can, hey, Squire?"

Fortworth agreed, with the sullen air of a buffalo-bull goaded by mosquitoes into a thoroughly dangerous state of mind.

"Then, just come in and take something to keep the cold out, and we'll lay old Corp on—if he's willing."

This they did. It was a warm night, but, as Mr. Bunn said, over a quick stimulator, it was liable to turn cold at any moment.

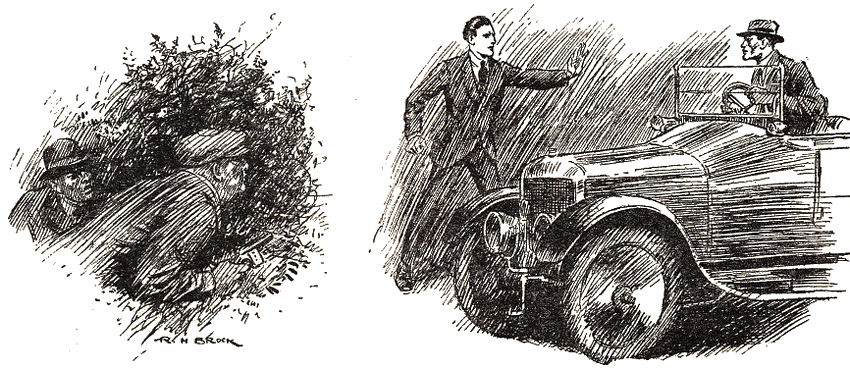

Within five minutes, Corporal, after muzzling the cap, had picked up the scent on the verandah, and was straining ominously against the strong steel chain with which Sing Song—as the fastest runner of the trio—was holding him in.

"Right? Better take our guns! We're on the side of law and order," said Mr. Bunn, dropping his automatic in his pocket. He added a flask to his armament and, pausing only to select from a stand in the hall an excessively butt-ended oak stick that would have been "highly recommended" in any shillelagh exhibition, he and his partner followed the Chinaman and the hound into the night.

"Ought to be in bed, as a matter of fact," he muttered as he went. He glanced up at the sky. It was clearing a little. Occasionally the moon peered anxiously from behind the black herd of wild-looking clouds that were sailing swiftly across the sky shepherded by a south-west wind.

"Shall be able to see our way—some of the time," said Mr. Bunn. "Get on, Sing. And keep the hound mute—and in hand. I don't envy the man he gets his jaws on this night! No, sir. And the man I get mine on will be a case for cauterising, believe me!"

RUNNING silently, his nose low to the ground, the black hound led them swiftly across the lawn along a narrow, winding path through the shrubbery to a small paddock. He hesitated a moment here, then picked up the scent again, and crossed the paddock to the boundary wall which divided the partners' comparatively modest domain from the deer park surrounding Harchester Hall. He checked at the wall, snuffling, and raising himself, his fore-paw against the wall.

"Hullo, what's this?" said Mr. Bunn, surprised. "Did Mr. Nighthawk come from the Hall? He certainly seems to have headed back there. Get the damn dog over, Sing, get him over," he added irritably. "We can't stand here admiring the back view of him all night!—"

Between them they lifted the hound over, and rather laboriously followed him.

He caught the trail at once and headed straight across the park towards the Hall.

"Don't understand this—don't understand it at all," panted Mr. Bunn, rolling after the Chink and his keen-scented guide, with Fortworth. "Don't know that I like it, either. Shall begin to ask myself a lot of awkward questions if we track Mr. Nighthawk to the Hall. What does anyone there want prowling around our place at this hour, hey?"

But, however that may have been, it was straight to the big house that the Corporal steered them.

He went without a falter past the big range of stabling and through a little maze of buildings and yards at the back, half-circled the huge stone pile and ran, whining low, to a standstill at a small, unobtrusive arched door, studded with heavy iron nailheads, behind a buttress angle at the side of the house.

Here, perforce, he halted; he set his heavy, wrinkled muzzle to the narrow crack between the stone sill and the door, and snuffed hungrily.

The partners stared.

"This is—very unexpected," said Mr. Bunn softly, mopping his brow. "He went in here—that's as sure as a rabbit goes to his hole. What are we going to do about it, hey?—"

He peered at the keyhole, and flashed his light over every inch of the door.

"Been oiled recently at the hinges," he muttered. "Some of it has leaked through. Not used a lot, I should say. New step—cement, too. Not stone. Evidently put in by someone in a hurry. Hasn't been dry long. Probably put in when they were getting it smartened up for the Vandermonde tenancy—though I don't see Patricia using this semi-back door much."

He scowled in the moonlight at his companions, thinking hard. "Let's look, now—we want to meet the lady, anyway. How would it be to knock her up and notify her that we've just chased a burglar into her establishment? It ain't strictly true, no doubt, but it would be the civil thing and a neighbourly act, and it ought to get a neighbourly friendship well started." Fortworth grunted slightly.

"I don't see that—and I doubt it. I shouldn't feel that I owed any friendship to any guy that chased a thief out of his house into mine," he demurred.

"He led us here—and he's no thief," explained Mr. Bunn. "However, perhaps you're right, though probably you're wrong. Let's take a look round—as we're here."

There could be no harm in that and they proceeded to act accordingly, moving quietly and cautiously round to the front of the big house.

Except for a window or two on the first floor and one on the ground floor, the place was in darkness.

The curtains of the lower windows were only partially drawn, and leaving the others in the deep shadow of one of the enormous cedar trees which dotted the wide area of roughly circular lawn before the west front of the house, and around which the wide carriage drive circled, Mr. Bunn moved cautiously to this window to investigate.

Peering in, over the heavy stone sill, he saw a large and comfortable study or library, extremely well furnished, brightly lighted and with a blazing fire, before which, at a big writing table, sat a man, his back to the fire, his profile to Mr. Bunn.

He was a youngish man, with keen, bold features, Smiler judged, and he seemed to be extremely busy with some of the many papers and books on the table before him.

"Looks like the secretary putting in a little overtime on his accounts," hazarded the old adventurer in his mind as he watched.

Even as he decided this the man in the library glanced at a clock behind him and verified the clock by his watch. He frowned a little, thrust aside his papers, and drummed his fingers lightly on the table.

Then he lit a cigarette, jumped up and turned towards the window. Mr. Bunn dropped silently into the shadow under the sill. A moment later he heard the click of a window catch released and almost immediately over his head a window swung open.

"Hah, that's better," said the man who had opened it, drawing a deep breath.

Mr. Bunn lay still. He knew that only a few feet above him the occupant of the room, probably grateful for a breath of cool night air, after the heated atmosphere within, was standing at the open window staring out.

"Nearly two—they should be here," mused the man, quite audibly. "And—if that light means anything here they come!"

Mr. Bunn heard the faint shuffle of a slipper on the oak floor, waited a few seconds, caught a slight chink of glasses from inside the room and softly raised his head.

The man had left the window, closing it behind him.

With extreme caution, Mr. Bunn peered in again through the narrow opening of the curtains. The "overtime" worker was fiddling at a cellaret at one side of the room, producing decanters and glasses which he set on the table at which he had been working.

Then, from over the carriage sweep, issuing apparently from under the inky shadows around the trunk of the cedar, came a tiny sound—a faint hiss.

Mr. Bunn heard it, understood it, and silently retreated from the window to rejoin his fellow prowlers in the shadows.

"What is it? Somebody coming, hey?—"

"Looks like it—a car with lights has pulled up somewhere down by the entrance to the park," muttered Fortworth.

"Ah—he's expecting somebody. Queer time o' night for visitors. We'll watch this. May mean nothing—but we'll see. Keep the dog quiet or there will be trouble, Sing."

They waited silently, peering from behind the cedar trunk down the drive that paled and darkened intermittently as the clouds overhead veiled and unveiled the moon.

"Here they are. Nice time of night to pay a friendly visit," breathed Mr. Bunn.

Three dark figures were coming up the drive to the house. Walking close in to the side, on the mossy turf, they made no sound. There were two men and a woman in a long cloak.

Softly these people of the night approached the house, and the watchers saw the great main door open soundlessly for a foot or two to receive them. It was as though a gap in a cliff had opened and they had vanished through it.

Instantly Mr. Bunn swung into action.

"Scoot away down the drive and get their car number, Squire," he instructed his partner. "Watch out for the driver—he'll be a wideawake wolf, if I'm any judge. There's a big mix-up here—Chinese puzzle, you may say—but we'll get to the bottom of it, or you can call me no conjurer. Sing, stop here, and keep the dog muffled."

He went soundlessly across to the window again....

Somebody had taken a passing pluck at the curtains again and the gap had narrowed. But it was not closed, though Mr. Bunn's range of vision was restricted.