RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Blue Book Magazine, December 1927, with "Captain Cormorant Proposes"

The first of a notably amusing series by the artist of humor who produced the Winnie O'Wynn stories and "The Easy Street Experts."

"NOTHING could have been more civil and gentlemanly than the way the secretary wrote to my wife, to express his regrets that the committee wasn't able to accept her offer to take the part of Venus in the Classical Handicap—I mean, Pageant—owing to their already having made arrangements for the part of Venus," said Captain Cormorant to a few friends in the smoking-room of the club at Havensea. He wiped his mustache. "And it only shows you what a low hound the man must be to think it humorous to go about the town afterward saying that he'd sort of planned to offer her the part of the Gorgon Medusa!"

Few of them had ever heard of the Gorgon Medusa, but they agreed with the Captain—a distinguished visitor to their seaside town. He continued:

"When a lady shows sufficient public spirit to volunteer for these affairs she ought to have every encouragement, and it is by no means creditable to the organizers to have turned down a lady like my wife. Naturally, she treats it with contempt, but it rankles. As she said to me this morning: 'It is not as if I were tied to the part of Venus. There are other parts. I would have accepted Diana, Minerva or Ariadne or Circe or Andromeda or Psyche—"

"But, Captain, honestly now, she isn't quite one's idea of Psyche, is she now?" said young Everman, who, being articled to an architect, was for some obscure reason regarded as rather an authority on the classics.

The Captain leveled his monocle in a glassy gaze upon Everman.

"That is a matter of personal taste and fancy," he replied, "and although I don't claim that my wife is any Psyche or Venus, I'll say this—my wife's worth three thousand pounds a year and she's beautiful to me. She's a noble woman. If every other man who lived on his wife's means, as I do—God forgive me!—were as happy as I am, this world would be a better place, my boy!

"I proposed to my wife in the dark," he continued, after selecting a cigar from the assortment a steward offered, snipping off the end of his cigar, and paused impressively. "I say I proposed to Mrs. Cormorant in the dark, and I've never regretted it. I don't say I should have proposed to her in the daylight so quickly—but it would have made no difference in the end, for daylight or dark, nothing can conceal that noble woman's beautiful nature nor can any criticism alter the fact that she pays income tax on three thousand jimmies per annum."

HE paused a moment to deal with the remaining contents of his glass and adjust the extraordinarily long, drooping mustache which, after his great Roman nose, was his most salient feature.

"In any case I hold that if a lady is cunningly gypped out of the part of Venus, the least the secretary can do is to offer her the part of Psyche. Particularly so when she is prepared to send a contribution of ten pounds to the Pageant."

He produced an elegant note-case from which he extracted a check.

"There it is," he said. "Ten pounds payable to 'bearer.' Had the secretary been a sensible, tactful man, with a kindly disposition, like mine, he would have offered her, say, at least, Helen of Troy, and received this identical tenner. As it is,"—he smiled sadly and put the check away,—"I sponged on my lady-wife for it—Lord help me!—and she let me have it cheerfully.

"'I suppose I'm not beautiful enough to be offered a part in the Pageant,' she said.

"'Beautiful is as beautiful does, my dear,' I said. 'And the first man I hear impugn your personal charms I shall cripple for life.'

"So she gave me the check.

"'I will say for you, Lester, that you are the best husband any wife ever had, even if you are unmoral,' she said.

"'Unmoral?'" asked Taylor, the mayor's brother. "How d'you mean? Immoral is the right word, I take it?"

The Captain smiled.

"No, Taylor; you take it wrongly. No less immoral man than I am draws breath. I'm non-moral—I haven't got any morals, good or bad. I'm not a good man, because I haven't got any moral principles—but I'm not a bad man, because I haven't got any immoral ideas. It is the way I was born. And it's a terrible affliction. An unmoral man such as myself comes into the world doomed beforehand to a life of extreme misery, dull wretchedness, and continuous unhappiness. You, gentlemen, who have to work, more or less, for your livings are happier men than I, who get practically everything I need for the mere humiliation of asking my wife—God forgive me!—for it. I suffer the torments of the damned every day and all day, owing to having been born unmoral."

Smilingly he took his now brimming glass from the attentive steward.

"The torments of the damned—no doubt of it," he said.

"From boyhood upwards, and in all parts of the world the unfortunate omission of morals from my make-up has made life tragic for me. As a boy, I, with my little companions, was wont in our innocent rambles to 'codge' apples from a big orchard near the village—full of grand old Quarrenden trees. One day we were caught.

"But he was a fine old sportsman, the farmer, and he let us off upon our each giving a solemn promise never to take another single Quarrenden from the orchard. I kept my word. From that day till the time I left the village by request I never touched another Quarrenden. But I found an orange pippin tree in a corner of the orchard nearer the house, and it kept me tolerably well supplied most seasons. I made friends with that farmer's dog—an unmoral dog, I found out, heaven help it. I've never regretted the bushels of pippins I've had off that tree—I never shall. It's one of the penalties of being born unmoral, as I was."

THE CAPTAIN shook his head. "My wife knows my infirmity," he added. "In fact, it was due to it that we met. Had I not been born a victim of this incurable affliction, I might never have met, or known of, the noble woman who now, to my shame be it said, supports me with such royal generosity, and encompassed me with such an enviable atmosphere of affection and plenty."

"How did you come to meet her, Captain?" asked Taylor.

Captain Cormorant smiled.

"Well, it's an interesting story, and as you all know my tragedy, there is no harm in telling you."

He settled himself down more comfortably than ever.

IT was some years ago (he then continued), and I had landed in England fresh from a terrible failure to establish a big llama run in Patagonia. The young fellow who had advanced the bulk of the capital for the experiment had quarreled bitterly with me, and for the time I was thrown on my beam-ends. I had a strict agreement with all my family never to set foot in England again—this I had signed some years before in consideration of a small sum, paid to me for leaving the country, I am sorry to say—and consequently I could not apply to them for financial aid.

I was having a very rough journey indeed. I was plowing a lonely furrow, and it was on stony ground. The times generally were hard—very hard. Even moral men were feeling the pinch—and for an unmoral man things were truly awful.

I remember I used to sit in an attic over a garage in the neighborhood of Bedford Park which was run by a man called George Dailey, an erstwhile whip of my late father's hunt. Poor Dailey, he was a bankrupt himself, and so was his business, but so far he had succeeded in concealing the fact from his creditors. An extremely moral man himself, Dailey had from the days of his youth entertained for me a species of admiration which was practically violent. It was so profound that he did not try to imitate me or to model himself upon me—which was a very good thing for him. He appeared to believe that I was too shining an example for him to copy. In his humble way Dailey had often proved himself a very good friend to me—usually to his loss, poor fellow.

I was, then, sponging upon this old retainer of our family for shelter. Do I understand you to ask for particulars of my family, Taylor? Very well, I am not ashamed to say that my father was a baronet, and the younger son of the fourth Earl of Wrottonborough. I was his youngest, and least successful, son. You would not think so, perhaps, to look at me and to remember the depths to which I have sunk, but it is so. Yes, gentlemen, it is well on the tapis that an accident to a couple of my brothers may yet transform the lady—whom that measly haberdasher of a secretary considered a perfect Medusa for his piffling pageant—into Lady Cormorant; or a prolonged series of calamities, into the Countess of Wrottonborough. But, as I was saying when Taylor interrupted me, I was having a very bad time, at the expense of poor faithful Dailey, and it was quite obvious that something had to be done—and done quickly.

There came a friendly fog. It was not the worst kind of a London fog, but it was sufficiently putrid. On the evening of this fog I decided that I would not run up to town—partly because of the fog, but mainly because I possessed only the meager sum of ninepence. Dailey had had a bad week, and he could not manage more than a loan of ninepence that day. I spent the evening sitting in my attic, breathing in the odor of petrol, rubber and exhaust smoke which characterizes these establishments, planning my next attack upon the impregnable fortress of my family's finances; and at perhaps half-past ten I decided to stroll out to the local hostelry and have a modest drink. This I did. Bedford Park is a quiet place at the best of times. That night, enwrapped in its heavy clinging cloak of fog, it was like a deserted suburb of Ghostland. Nothing moved, nothing was to be heard. One could see, perhaps, two yards in front of one, but no more. Cutting through a side-street on my way inn-ward, I came upon a big motorcar drawn up at the side of the pavement—a very good, almost new Arrowhead landaulet.

I paused a moment to admire the car. Peering at it through the dense fog, I perceived that there was no chauffeur with it. I looked inside. It was empty. I glanced at the gate before which it stood. The gate was closed. Why this should strike me as curious I am unable to say, but it did.

I continued my investigations. I went in through the gate, up to the house. The house was silent and unlighted. Evidently the occupants had all gone to bed, or were out.

I stood on the lawn, listening. But I heard nothing except the drip of water from the fog-bound trees and shrubs.

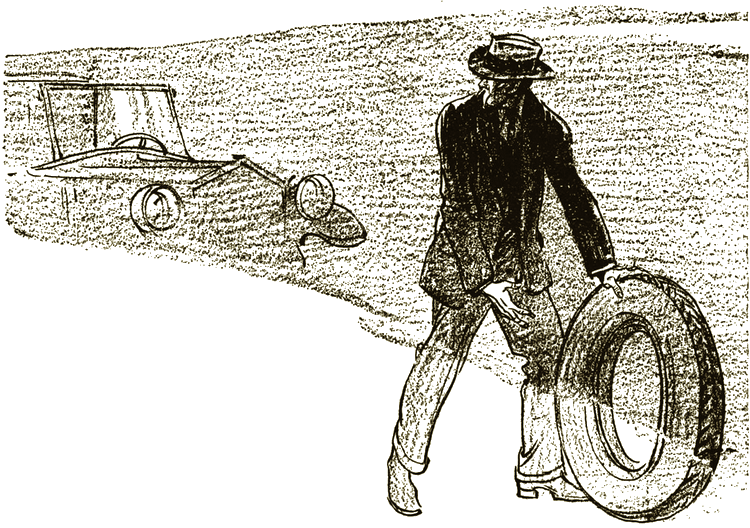

I returned to the car and stole the spare tire, I am ashamed to say.

I returned to the car and stole the spare tire.

SWIFTLY I rolled it through the kindly, sound-muffling fog, back to my lair, deposited it in my attic, lit a cigarette, and went out to get the refreshment I had originally planned. It was still quiet, and the fog was denser than ever.

On my way I had, of course, to pass the car—that beautiful Arrowhead landaulet.

The chauffeur, I observed, had not returned.

There it stood, alone, unattended, its lamps sending rich, warm beams of light into the clammy curtains of fog. They were magnificent lamps. The headlights were a pair of very fine self-contained acetylenes—this was slightly before the advent of electric headlamps. I—er—pinched them forthwith. You begin to see now, gentlemen, what a tragic thing it is to be unmoral? One is never safe from temptation. A kleptomaniac lives in perfect safety compared with one who, like me, has been born unmoral.

As I say, I secured the lamps for myself, also a very charming little carriage-clock on the dash—merely a matter of a couple of screws or so. (The toolbox was unlocked, yes, Taylor.)

I journeyed again to my attic. It was beginning to get quite a well-furnished look. The clock went admirably upon the mantelpiece.

"Lester, my boy," I said to myself, "you have deserved a little modest refreshment; yes, indeed."

And I sallied forth into the chill silences of the fog again.

It was in the immediate neighborhood of the Arrowhead landaulet that the silence and loneliness were most marked. It was, indeed, so silent and so lonely that it would have been ludicrous to leave the speedometer—a very fine bit of work —upon it.

So I collected it, took it home, and returned to the car for the magneto. After all, why leave a good magneto?

To a man of my experience it is a matter of seconds to take the mag' out of a motor, and especially out of a car which is notoriously the most "accessible" car on the market.

Rendered confident by my unexampled run of luck, I had opened the bonnet, when it occurred to me that I was wasting time.

Why do the thing by installments?

It would take me a long time to remove the car by fragments. Skillful with the mechanism of the motor as I was, nevertheless, I should inevitably have trouble with the transmission, and if not with the transmission, then with the engine.

Why not take the car? It would be simpler and save time. I reflected: I needed a car. Here was a car—complete except for a spare wheel, headlamps, clock and speedometer. And I knew where to get these accessories. I replaced the magneto, and pondering, cranked her. She started, ticking over as sweetly as a pleasant dream, murmuring a little happy song to herself.

I got into the driver's seat, and took off the handbrake. It worked very sweetly. Evidently a fine example of Arrowhead enterprise.

I depressed the clutch pedal—it worked like velvet—and delicately dropped the gear-lever into first speed. I gave the accelerator a touch, let in the clutch, and lo, we glided dreamily into the fog, practically without sound. It was all very disgraceful.

I had got a good car, and I knew it.

I DECIDED to take myself for a run into the country. Pausing for a brief moment to collect the headlamps and to throw a few things into a suitcase, I drove the Arrowhead quietly out of London and away into the country.

I was making for a certain village not far from Basingstoke, where on a retired farm in that rather spacious, lonely district, dwelt another old retainer of my father—one Butts, an ex-bailiff. Butts had married Mary, an old nurse of mine, and both of these good, honest, worthy folk were once, like Dailey, allies of mine. More than once I had, I grieve to say, battened most unmorally upon their hospitality.

You see what a curse my infirmity is, gentlemen. It follows me everywhere. Still, I confess I enjoyed the drive. It was most pleasant. After a long period of roaring, jerking motor-busses, of grinding trams, of earthy tubes, it is a very great luxury to travel in a really good, well-made car. At any rate I found it so.

I took it easy in the town, but I pushed her rather when we had come out into the country.

We went purring sweetly through the clear, cool night, for the fog we had left behind; and I confess, gentlemen, I had never enjoyed a drive so much before. I could have sung—indeed I did sing—a scrap or so. Old favorites of mine, "I would that my love would silently flow—flow like a beautiful stream" and that other exquisite thing, "Oh, that we two were maying!" which always brings the tears to my eyes; that wonderful song, so sad, so wistful—

FOR one fleeting moment the voice of the hard-bitten old adventurer faltered, and the heavy-lidded eyes grew absent. The mask was off.

"Oh, that we two were maying," he repeated, staring down God knows what dim, beautiful, rose-decked vistas of the past, perhaps to seek or to see again some lovely ghost of his youth, long vanished, who would never return. Then his eyes cleared again, and he resumed:

Yes, it was very—pleasant. Then, a few miles from our destination some little trivial thing went wrong with my right headlamp. I stopped, got out to adjust it, and as I did so I received the surprise of my life.

"Are we not nearly there, Roy darling?" said a voice, so musical, so soft, so caressing that for a moment I could not believe it human.

I was on a lonely stretch, so that a glance both ways assured me that there was nobody in the road near enough to be seen—yes, it was moonlight, Taylor—and I was wondering whether I had not imagined it when the voice came again:

"Roy dear, aren't we nearly there?"

It came from the interior of the landaulet, gentlemen, and for a moment my legs felt as though they were made of pure leather.

A lady in the car I had stolen! A lady who called me "Roy darlingl"

Evidently this little matter of procuring a new car was to be rather more complicated than I expected.

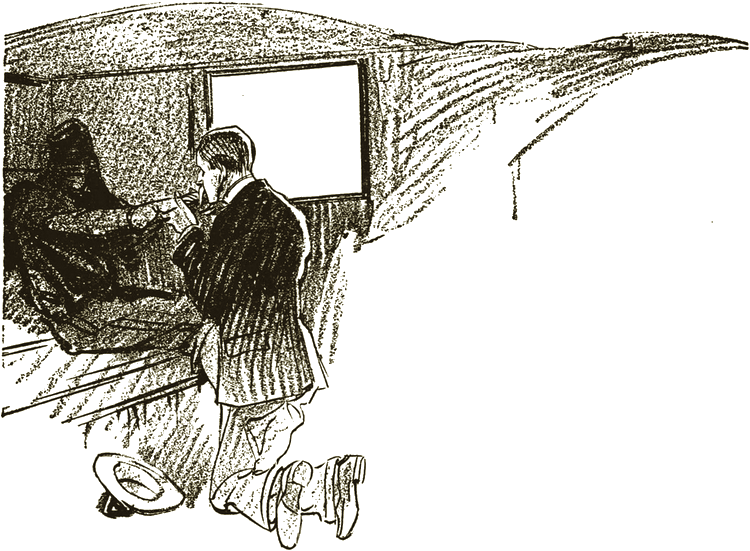

I HESITATED—on the point of bolting for it. But I am not good at bolting, so with a violent effort I went to the door of the car, and removing my hat, looked within.

Either there was no interior light or it had failed, for the inside of the car was in a moon-ameliorated darkness—moon-ameliorated, Taylor, is a literary touch merely—a fanciful way of saying that the darkness of the car was lightened by the light of the moon. I was perhaps a little carried away by the romance of it.

In the silvery shadows of the warm gloom, scented with the smell of fine leather upholstery, of some rare and costly perfume, of delicate femininity—in that enchanted gloom, I say, I saw yearning as it were to me, a woman's face seemingly white as pearl, gleaming through the dusky folds of a veil.

"Roy darling," she said, in her matchless voice, "I'm tired and nervous. Shall we soon be—home?"

Home! A pang struck through me as I remembered that if she were the owner of the car and of a severe and vindictive nature, I should shortly be in a place not at all like home.

I bowed my head.

"Alas, dear lady," I said, in my very best manner—which on account of my breeding is naturally rather good, "there is a—misunderstanding. When I drove this magnificent car away, I was wholly unaware that it was freighted with—shall I say—loveliness so rare that it is only equaled by the music of the voice by which it makes its presence manifest. I believed it to be an empty car, deserted, abandoned in the fog, maybe, by some wealthy man whose nerve may have failed him, and who, rich enough to abandon the car as a mere bagatelle, had left it and consigned himself to the care of a taxi-driver. In the hope of securing the reward which he might later offer for the recovery of the car, I was driving it to a safe place."

It was pretty thin, yes, Taylor. But, heaven forgive me, that was the hashish-dream I wafted toward the owner of that white, half-seen, half-guessed face and that glorious voice. Also it was, maybe, a trifle theatrical. But a touch, a soupçon of theatricality usually goes very well with a lady.

She sank back, gasping.

For a moment there was silence. Then I heard a low sound—a catching of the breath. She was sobbing. It went to my heart.

"Ah, do not weep, I entreat you, dear lady, do not weep," I implored her in my best voice, which, on account of my experience in such matters, is pretty good. I tremolo-ed it a little. "Had I but dreamed that you were in the car I should not have touched it."

"But why—oh, why did you touch it? You have done a great deal of irretrievable harm."

"Each word you say, dearest lady, stabs me anew," I said. "You speak of irretrievable harm, but give me leave to put the car and its exquisite freight back where I found it, and I will drive if need be through the jaws of—er—Hades to do it. Try, O lady of the moonlight, try to regard me as your willing slave, as a machine which will do in all respects exactly what you command it to do—no more, no less."

"It is too late," she said, in accents of real despair. "What is the time? Look at the carriage-clock."

I feigned to look.

"Alas, dear lady, it would seem that one of those dastards, those wolves in human form prowling through the fog in London, has stolen the carriage-clock, for it is gone," I explained. "But as to the time,"—I made a guess at it—"it is close upon midnight."

"You have utterly ruined me!"

"I am utterly ashamed," I said humbly.

She seemed to key herself up a little.

"You have spoiled everything," she said; and the richness of her voice seemed to have changed subtly from the mellow richness of a ripe pear to the sharpish richness of not-quite-ripe grapes. It was still fruity, you understand, but there was a touch of acid in it. "You have wrecked my plans!"

"Heaven forgive me!" I said.

"You have destroyed my prospects of happiness!"

"I crawl in the dust at your feet," I answered abjectly.

"You have crushed under your heel the delicate fabric of a woman's carefully built-up romance!"

"I will repair and make good the evil I have done," I said.

"That is impossible," said she in tones of despair.

"May I humbly—most humbly—ask why?"

"I was—eloping," she said, her voice becoming tender again. "For certain reasons it was necessary for us to have my car brought round to the rear entrance of my house. I was to enter it quietly, and in a few moments my fiancé was to come, quietly take the wheel, and drive away. When I saw you take the driver's seat so quietly, I thought you were Roy."

GENTLEMEN, I assure you my hair crisped with horror at the thought that while I was so blithely disassembling that car in Bedford Park, building up, as it were, my little home, two people were edging in, converging on the car. It was amazing that I had not been—well, nabbed. As it was, so singular are the means and methods of Fate, I had myself nabbed the lady.

Dismissing an unworthy inclination to smile at the thought of that poor devil "Roy darling," waiting for the car back at Bedford Park, I pulled myself together, opened the door of the car, and stepped in.

She did not forbid it.

Her hand, gloved in a soft, whitish leather, lay on her lap, and I ventured to place my own upon it.

"Lady of the moonlight," I said, rather thrillingly, I fancied, "what am I to do—what am I to say? I have, inadvertently and with the best intentions, torn you and Roy asunder. You tell me that the disaster is irretrievable, and in so far as Roy is concerned, I fear it is. For I see, dear lady, that you have been placed in a singularly compromising position by my excess of zeal"—this took place in the era when unmarried ladies avoided compromising situations, instead of seeking them as apparently the matrimonial competition compels them to do nowadays—"and that nothing remains for me now but to make such poor amends as I may. Poor in this world's goods, dearest lady, I am—nay, I confess that I am utterly broke. But, thank God, I still have self-reliance. Deficient of morals, good or bad, I admit freely that I am—but, thank heaven, I still have manners. My reputation has long since left me, but my good taste and breeding are practically unimpaired.

"I am reduced to living in circumstances of great penury and discomfort, but my natural desires are for the best of everything—for the recherché. I am a grandson of the Earl of Wrottonborough, and I am free from the silken cords of any love-entanglement prior to this. My name is Cormorant, Captain Lester Cormorant, late of the Bolivian Light Horse." This was, of course, prior to the great "go" with Jerry the German, and my acceptance of a commission in the 429th Mud-Walloppers, as we all used to term the old regiment.

I pressed her hand, and she did not remove it.

"Suffer me to speak, dear lady, I beg," I continued, "and if I offend you, believe me it will only be in carrying out the duty of a gentleman—unfortunately poor and unmoral, but the grandson of an earl and the son of a baronet. Dearest lady, I have unwittingly been the cause of losing you your lover; nothing therefore remains but to do what any gentleman would do. If, sweet lady of the shadows, you care to accept, as some poor substitute for Roy, the poverty-stricken, remorseful man before you,"—I dropped on one knee, an awkward business in a landaulet,—"I only beg that you will take me!"

I have unwittingly been the cause of losing you your lover. Sweet lady of

the shadows, if you care to accept a substitute, I beg that you will take me.

I sobbed a little. I thought a sob seemed to be called for.

SHE appeared to be reflecting on my offer. "Do not let the matter of poverty distress you, Captain," she said softly. "I have three thousand a year."

I dropped on both knees at once. And emboldened, I pressed her glove to my lips.

"Your lightest wish shall be my life's ambition, Moonlight Lady."

"I cannot humiliate myself by returning to Bedford Park unwedded!" she said.

"Unthinkable!" I agreed.

"And so—all being well—when we know each other a little better—perhaps—"came that golden voice through the warm gloom, faltered and stopped.

What could a gentleman do?

I did it.

Timidly, she returned my embrace. Presently I drove on to Butt's place.

NOT till she stepped into Mary's well-lighted little parlor, hastily illuminated by my old nurse, whom I had to rout out, did I set eyes on the face of the noble-dispositioned woman who is now my lady-wife. Nay, more, my comrade.

I confess to you, gentlemen, that, on the whole, I was rather surprised; she was different, in some ways, from what the moonlight had led me to believe, and I do not deny that, like the darkness, she too had been perhaps a little moon-ameliorated. But when that is said, all is said. Her nature is like her voice—of purest gold. Her face—pshaw! Why this modern craze for dollish beauty, anyway? It is the curse of the country. Handsome is as handsome does. And on those lines my wife is the handsomest woman in the country.

We have been married now for a number of years, and I have never regretted it for a second. Nor, gentlemen, has she.

THE CAPTAIN finished his whisky-and-soda and rose. "What about Roy?" asked the man Taylor.

"We never inquired and he never complained. No gentleman, evidently."

"But why did she have to elope?"

"She was under the power of a brother—a scoundrel who terrorized her with threats. He had spent his inheritance, and he desired to live on her, the blackguard. He made a scene at our wedding, and I had to half wring his neck before he could see things in their proper perspective—for him."

"How?" pursued the person Taylor.

"The proper perspective of our wedding for him was, I conceive, as he finally viewed it from a bed of nettles in the churchyard ditch into which I chucked him."

"What happened to Dailey?" asked Taylor.

"He went bankrupt in the usual way— the usual way," said Captain Cormorant "And now he is the landlord of a cozy inn near Pulborough, in Sussex, which—God forgive me!—I persuaded my lady-wife to buy him!"

He smiled indulgently down upon the group from his towering six feet four inches.

"And now, my good friends, I must go to the admirable lunch which, instinct whispers in my ear, my dear wife has ordered for me, God bless her—"

A MAN entered suddenly. It was the secretary of the Pageant Committee. He looked flurried and perturbed—like a secretary who has just heard that he has lost a ten-pound note subscription to his "cause."

"Ah, Captain Cormorant, I've been looking all over the town for you! I'm sorry to say the lady who was to take the part of Psyche in the Pageant has had to go to Yorkshire. She will be away some time. May I have the very great pleasure of offering the part to Mrs. Cormorant?"

The Captain stiffened.

"You may offer it, sir, till you are black in the face," he said. "But, on behalf of my wife, I have very great pleasure in declining it. We are not interested in your infernal pageant, my good sir. It is highly probable that we shall be returning to our town house before the affair comes off. My wife would not dream, for an instant, of accepting other people's leavings, sir; and unmoral though I may have the misfortune to be, sir, I have yet enough pride in me to uphold—with violence, if necessary—her views!"

He swung on his heel.

"Good morning, gentlemen!"

At the door he paused in the middle of a highly effective exit to hurl this verbal javelin of irony at the dazed secretary.

"But if at any time you find that you have in your silly pageant a vacancy for the characterization of the Gorgon Medusa, sir, pray let me know!"

And so to luncheon.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.