RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

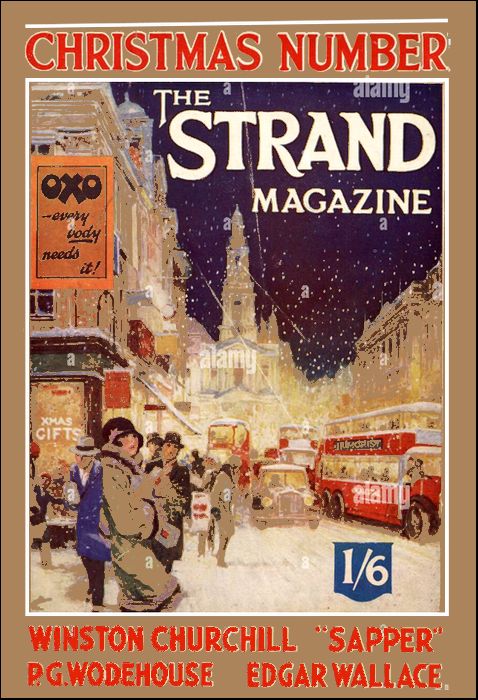

The Strand Magazine, December 1931, with "Captain Ken."

IT was during one of those temporary lulls in the conversation round the extremely well-populated supper-table at Chiddenham Hall that the robust and remotely brassy voice of August Chiddenham—nineteen years old but conscious that he possessed the wisdom of one double the age—broke upon the silence.

"The sudden-death epidemic among the yap-dogs of this parish continues," he said, in the manner of one who is effortlessly sardonic. "If anybody happens to be interested."

"What do you mean, August?" asked Mrs. Chiddenham.

"In plain English," added sister Ella, who, on occasion, really could be more than tolerably sarcastic.

August shrugged loftily. He was in the lofty stage of life.

"Oh, nothing of any importance, mother. I thought I'd mention it as a—a—curio of country life. Old Lady Downsmore's Peke has gone the way of all the local yap-dogs. So they say. Found just inside the drive gate as dead as last year's charity, The creature had a hole in its Peke-shaped body the size of a .22 bullet. Somebody shot it—probably it was asking to be shot—at the top of its voice!"

"But that's the third lap-dog that's been shot about here in the last two months," said Nelson Chiddenham.

"I really do think something ought to be done about it. It's perfectly clear that somebody is going about killing these—little dogs!" said sister Ella.

Fair August agreed in his own way.

"I know, I know," he said. "If Nelse's celebrated blood-dog was all we are advised to believe it is, it—it and Nelse—would track down this lap-dog killer in no time!" he stated more loudly.

This was such a time-worn back-hander at Nelson's bloodhound-setter, Red Sleuth, that Nelson did not even stop eating his honest supper. He was accustomed to Aug.

But Aug had set vibrating in his mind a string that was already awaiting vibration. It was odd, this singular mortality among the small pet dogs of the neighbourhood.

As Nelson had said, this was the third. All found dead, all perforated—bullet-holed, as one might say.

Another point suggested itself—a very practical one.

"Is Lady Downsmore offering a reward, d'you know, Aug?" asked Nelson.

Aug stared at his young brother—his "one best bet" for a real crushing repartee.

"Dogs'-bodies..." said Aug, and thought it out. "Ye-ss. A bad-tempered figure, Nelse—Twenty-Five Pounds Reward, They say she will actually pay it to whomsoever will produce evidence that will lead to a conviction of the person who killed her Peke!"

Sister Ella chimed in, acidly.

"I should never seek to charge Nelson with an embarrassing surplus of brains," she declared. "But fair is fair—and if there really is a number of rewards being offered for these canine murders, then, if I were Nelson, I should at least endeavour to give that lumbering red dog of his an opportunity of earning his keep!"

It was, for Ella, a friendly hint, though late.

Nelson had already decided to circle around the problem. Lady Downsmore's reward of twenty-five pounds, plus that one of Mrs. Morehouse, five pounds, and a third offered by a Miss Tollemache, ten pounds, made a very handsome total of forty pounds.

A GOOD deal of thought, much inquiry, and a lot of hard walking during the next week, at last produced an idea —sketchy, but worth trying.

This idea brought Nelson and Red one afternoon at about two o'clock to the green-painted gate of a carriage-drive that opened on to a delightful lane, some two miles out of Chiddenham village.

Nelson and Red hovered for awhile about this gate—the carriage entrance to the house of Miss Pallis, a new-comer to the neighbourhood.

Presently Nelson kicked it, and almost instantly the noisiest little Peke in the South of England came galloping furiously down the drive, most vociferously ferocious.

It was a good house-dog, in its way.

It danced about at them, and called them accursed. It said "Yap!" at them almost unceasingly.

It seemed to be divided in its mind about Nelson and Red and the gate-posts. It seemed to be labouring under the delusion that Nelson and Red had done something injurious to the gate-posts, and were liable to do it again if not severely warned off.

It was, in fact, a very good, a very honest, and very pretty little Peke dog—though somewhat over-vocal.

Certainly it, or something to do with it, urged Nelson Chiddenham and his red animal into a species of ambush opposite the gate, where they crouched for what seemed to be a long, a very long, time.

In the end the Peke wearied of his maledictions, and went back to the house at the end of the drive.

For three days in succession Nelson Chiddenham and his dog Red Sleuth did this.

And on the third day, at about two o'clock, just before the Peke returned to the house after its usual greetings to Nelson, a person arrived at the green gate who seemed to be possessed of the unclean spirits of Impatience and Intolerance.

For he leaned over the gate, having glanced about him, and, aiming with very great care, he brought to bear upon the thoroughly annoyed Peke a thing exactly like a walking-stick, but which was evidently that vastly different thing, a walking-stick rifle—for it said in an irascible sort of way, "Pha-uff!"

The Peke gave a galvanic leap, fell on its side, and then was completely still, and very silent—for it had a hole through it that would have shocked the inventor of holes himself.

The killer leaned over the gate, smiled, and passed on, muttering to himself. He was a tall, good-looking man, nearing middle-age, well dressed in a country-life sort of way.

From their covert Nelson and Co. saw that he was trying to unscrew something from the end of his lethal walking-stick—and failing, for he stopped and bent, laid it over his knee and twisted. Evidently his hand slipped. They heard him swear angrily. Then he took a glove from his pocket and gripped again, failed again, and with a furious oath flung all into the ditch. He strode on, then suddenly turned back, retrieved the walking-stick, and went away.

Nelson Rodney Drake Chiddenham's numerous reddish hairs slowly sank from the strictly vertical position which they had assumed.

"D'you know who that was. Red? That was Captain Kennedy—Captain Ken, as they call him. Captain Kennedy—a friend of Sir Milner's and a friend of father's, and the very best shot at high pheasants or driven grouse that ever I saw—or father or Sir Milner either. They said so, Red. He was up at Sir Milner's in Scotland when we were—and you've retrieved his birds—you have, Red!"

The boy's face was white—it would have been frightened if Nelson had been an easily frightened youth.

"No need to pick up that glove and track him home. Red," he said, presently. "And yet "

He pressed the bloodhound-setter slightly, and they flattened themselves as a lady came down the drive rather quickly.

She walked straight to the dead Peke, picked it up, examined it, found the bullet hole, and put the poor little beast gently down on the turf at the roadside.

She came out from the drive and looked up and down the lane. Nelson had never seen her before—but he judged her to be the new owner of the house, Miss Pallis.

He thought her face would have been one of the loveliest he had ever seen if it had not been so thin and so sad. She was graceful, too, he thought, tall and slender, though not very young. Very fair, but her hair was nearer silver than gold—though, indeed, there was something of wasted gold about it, too.x

Nelson Chiddenham was not a connoisseur of beauty, but he was quite ready to adore this slim, pale lady.

He lay close in his covert with his familiar, the cross-bred bloodhound, until she lady picked up the Peke, walked up the drive, and passed out of sight.

NELSON thought for a moment, then emerged, picked up the glove, and laid Red on the dog-destroyer's trail. It was not in the least necessary, but it was an opportunity for a little useful practice, and the were not so frequent that Nelson cared to throw one away.

There was no difficulty about it. They went down the lane, which a little distance further on continued across the main road. They followed it—and rather unexpectedly ran into August, his motor-bike, and a pretty girl. August, who should have been at a land-agent's office in the town, looked for a moment disconcerted, then angry, as Nelson raised his cap and limped past after Red.

"Doing a little with the Hound of the Baskervilles, I see," gibed August, pleasantly.

But Nelson was gone.

The lane ran out on to the wide downs. Far across the sheep-cropped, undulating downland moved a man. He was walking briskly towards a distant house—Lonely, but beautifully situated, a big place. This was Hartford Hall—Kennedy's home.

Nelson checked Red and followed on without haste.

Twenty minutes later they were walking up the drive to the Hall—not quickly, for Nelson was just a trifle dubious about what he was going to do, or say.

He was j great admirer of Captain Kennedy—a man with a fine War record, Squire Chiddenham had once said, a first-class shot, a splendid horseman, with a quietly genial manner. He popularly known as Captain Ken, and, as Nelson knew, was a great admirer of dogs—indeed, he specialised in harlequin Great Danes, huge pied monsters, a dozen or more of which were always haunting about Hartsford Hall.

"If I hadn't seen him shoot that Peke, Red—seen him with my own eves. I wouldn't have believed it," declared Nelson. "It's going to be awkward, but—well"—he concluded a little desperately—"it can't go on. He'll be caught one day—and there'll be an awful scandal!"

He went on, puzzling as be went.

Five monstrous pied dogs, almost as big as donkeys, strolled majestically up and looked them over.

Nelson and Red went on, escorted by the pied gentlemen—perfectly quiet, well-trained dogs, but not by any means the type of canine to pick a quarrel with.

Captain Ken, in the hall, saw them coming and strolled out to the big porch to meet them. His face was whitish and, Nelson thought, a little strained-looking. For a moment the Captain stared absently at Nelson and his dog, almost as if he failed to recognize them. Then he smiled.

"Why, hullo, Nelson Chiddenham—what are you up to out here;—to pinch some of my dogs? Come in and have some lemonade or something. Still got Red Whatchamacallim, I see. Good as ever, I suppose."

He steered Nelson and Red into the house.

Five Great Danes followed to the threshold, halted there, and looked inquiringly at the Captain, who shook his head. There were five full-sized sighs and they all walked back to the shade under a big lawn beech from which they had first issued.

"Awfully well-behaved dogs, sir," said Nelson, interested.

"Oh, well, they naturally do as they are told. Any disobedient dog gives me the horrors—but a disobedient Great Dane would give me the howling St. Vitus's dance—whatever that may be. Sit down, old chap . How came you to be this way?"

Nelson flushed.

"Well. I—" He hesitated, then put the glove on the table.

"I found this is glove," he said. "And I thought I'd better return it at once, sir!"

The Captain looked steadily at the crumpled leather glove. An extraordinary expression dawned slowly on his face.

"This—this glove, heh?" he said after a pause. Nelson saw that his hands were clenched so tightly that the knuckles were white.

"How d'ye know that's my glove, Nelson?" he asked presently. "It might—"

An enormous Great Dane scratched lightly at the big bay window from outside—evidently an old favourite—and the Captain wheeled with a reproof so violent and harsh that it was ferocious

The great dog faded from the window as if the Captain had lashed it across the eyes with a heavy whip. Nelson was startled at that—but he was rather glad about it a little later.

"This glove, Nelson—how d'you known it's mine?"

Nelson stiffened himself—and faced it.

"I saw you drop it—about an hour ago," he said as coolly as he could, though there was just a suggestion of gasp about it!

The Captain went to a sideboard and with extraordinary swiftness poured and drank a stiff whisky-and-soda

"Where?" he demanded sharply

"In the lane," said Nelson simply.

The Captain's face was the colour of bone. But a strange and rather scaring glow was lighting itself in his eyes.

"In the lane—what lane—where?"

"Just outside the green gate," said Nelson curtly—not because he felt curt, but because he felt quite a little scared and couldn't show it.

"I see—I see. Thanks, Nelson—thanks! I —think I like your style, Nelson old man..." The Captain strode up and down a few times. It would not have strained the perception of a child to understand that he was, for some reason, fighting desperately for self-control.

"Did anyone see you, my boy?"

"No, sir. I picked it up and came after you."

The Captain gripped Nelson's shoulder " You're a good chap, young Nelson. I wish a chap like you were a few years older. Bayliss told me you were a little sportsman in spite of your game leg and your glasses and things—"

He broke off and sat down at the table, staring at Nelson with eyes that shone like grey-blue water with a wintry sun on it.

"Let's understand each other. Nelson," he said, and drummed softly on the shining surface of the table with his fist. "You saw me throw away the glove?"

"Yes—when the silencer wouldn't unscrew," said Nelson—so that the Captain should understand that he had seen everything

"You mean that you saw me shoot that yapping Chinese insect?"

"Yes, Captain Kennedy. I did!"

Nelson saw Red's hackles like the spines of the alleged-to-be-fretful porcupine, as the Captain's fist crashed on the table like the blow of a hammer.

"Not Captain Kennedy! Captain Kennedy Insecticide! Insect-killer! Weed-killer! That's my name—Insecticide! I kill the little vermin like flies—like wasps—like beetles. Nelson! A man's got a tight to kill vermin, hasn't be? A doctor's got a right to kill microbes—bacteria—whatever the bugs are called, hasn't he?" The Captain was shouting now.

NELSON, with one eye, saw a surge of Great Danes roused by the Captain's voice, weaving about the big window like a pack of gigantic foxhounds, but they did not touch the glass, for they tad been rigorously well-trained.

"I kill 'em. Nelson, when I get a good chance. Kill 'em! Hey Why not? Y'see, the little vermin killed the only thing on this green earth that ever meant anything to me! Killed her! Contagion— infection—what's the word? She used to kiss the little devils—when I hadn't the pluck to ask her to kiss me because I respected her as if she were a goddess! She was the loveliest girl in the world, so trim and sweet and slim and graceful and so kind—the very kindest of all. Only she loved these lap devils—used to kiss them and fondle them—and send them all out for a romp and scramble. It was pretty enough—but you understand dogs and so do I—and you know, as I know, that a dog is first of all a dog. And dogs were not designed for drawing-room pets, to be kissed and fondled!"

He was talking very fast and violently, beating his left fist in the palm of his right hand savagely.

"It's natural for a dog when he's out of doors to go nosing and prying and poking about. Half their senses are in their noses. Her dogs used to go scampering about—very pretty and all that—but just as dirty, from a sane, human point of view, as any other dog!"

His brows were knotted and every few second he shut his eyes tightly for the length of a few sentences. He was like a man in intense pain.

"Even now—at this very minute, Nelson—there are scores, of pretty, dainty, sweet women kissing little dog that have come straight from some ash-can, some garbage or other, my God! They—the women don't know. At least, they won't think. Nelson, one or other of those dogs killed my girl—some foul infection! How can a woman with some trivial abrasion—some minute scratch on her pretty lip or chin—kiss a dog! Kiss a dog, my Goo—when she would shrink squealing from some tramp fresh from even a workhouse bath. Give me the tramp. I love dogs. Nelson—I always have—but as dogs. Look at my Great Danes—gentlemen—ladies!—all of 'em! But kiss 'em! I? Would you? These little silky tykes—good little devils if they were well-schooled—get spoiled and when they aren't watched are just as nasty as any other unwatched dog. Is that a lie—or is it the stark-naked truth, Nelson?"

The Captain paused, staring hard at Nelson But he could only have seen him through a mist, for now tears, great wrung-out tears, were rolling down his stone-white face.

"Yes, it's true!" said Nelson, honestly, for he knew it was true.

Captain Ken's voice leaped up again.

"That's why I kill 'em. I left my girl and went to France with her promise to marry me when I came back—on my first leave—and one of the toy dogs killed her dead before I could get home! That's why I kill 'em!"

His voice was suddenly a shout, his eyes glared,

"I've killed scores—I'll kill hundreds—thousands—I've got the money to pay for 'em—an I can shoot—"

He was almost screaming now—and outside the perturbed and excited Great Danes were baying furiously—glaring in: and every single hair on Red's back was bristling. Nelson was scared stiff, but dared not show it. The Captain was mad—he understood now—mad on this subject, at least—sane about everything else.

"Kill 'em—kill 'em, I say " shouted Captain Ken—and wheeled ferociously us the door opened and a burly man. very light on his feet, stepped in.

"Why. sir—I—"

"Get out of it, Lake! Who gave you leave to butt in here? Get out or I'll—"

The Captain rushed at him. dangerously—and the man, Lake, slid a clean, crisp, extraordinarily fast punch to his employer's jaw that laid Captain Ken on the floor, all but unconscious.

The man turned to Nelson, his rugged face working.

"An' that's what I'm paid to do, sir," he said, apologetically. "Every now and then—to the Captain—the man who saved my life twice over there—under the machine-guns. If you don't mind my saying so, you'd better leave him, sir!"

He knelt down by Captain Ken. speaking quietly, soothingly, like a woman picking up a child that has fallen on the sharp gravel path. He was evidently a sort of valet-attendant.

Nelson got up.

"Heel, Red!" he said mechanically, and went out.

The Great Danes were not pleased with him, and said so.

But Nelson was not afraid of dogs, and the dogs knew it, as dogs do, Moreover, Nelson had something else to worry about, as he went limping miserably homewards across the downs.

"Captain Ken! Who ever would have thought that be went about with this trouble always—always—kind of gnawing at him," said Nelson as he went, feeling wholly helpless about it.

Over an undulation of the downs a first-rate light hunter came cantering, ridden by the slender lady Nelson had seen at the green gate in the lane.

She reined in as she approached and asked Nelson if she were on the right track to Hartsford Hall—Captain Kennedy s house.

Nelson said "yes" —but he never quite understood why he added that Captain Kennedy was not well that afternoon. He saw her face, more beautiful than ever from the pink flush which the riding had given it, suddenly blanch and her wide eyes darken.

"Ill!"

Nelson made haste to reassure her. He explained that he had just left the Captain, who was not exactly ill but was a little upset about something.

"Was it serious, do you know?" She seemed extraordinarily anxious

"No," said Nelson. "Something about one of the dogs." He hazarded that probably everything would be all right in the morning.

She looked very searchingly indeed at Nelson—far too penetratingly for one's comfort.

"You are a friend of Captain Kennedy?" she asked.

Nelson claimed to be that, and they exchanged names and, so to put it, addresses.

She seemed to hesitate, to hang, as it were, undecided. Her horse moved about fretfully, and she dismounted.

"Tell me. Nelson—you don't mind my calling you Nelson?—is the Captain upset about one of his own great dogs (I have heard of them) or about some other dog—a—for instance—a toy dog—a dead Pekingese? Do you know that?"

Nelson hesitated in his turn. He could see that this lady was no enemy of the Captain, and so he fell back on the truth— the good, old, unpleasant but oddly reliable truth.

"Yes, Miss Pallis. It's about a dead Peke," he said. Her blue eyes pierced him.

"A Peke that—that died near the gates of my house in Grove Lane this afternoon?" she asked.

Nelson must have been inspired, for he nodded.

One band on the bridle rein of her horse, she drew near, and the other hand Nelson suddenly fell, light as a flower, on his shoulder.

"Captain Kennedy is a dear friend of mine. Nelson," she said, "and I want to help him, Don't you? Let's exchange confidences, Nelson,"

Her voice was the voice of a siren, but the music of her voice would not have helped her if Nelson had not sensed that she was very much indeed what she claimed to be—a friend of Captain Ken's.

They exchanged confidences— it was nearing tea-time when presently Nelson, with his red shadow at his heel went, limping across the main road on the short cut home.

A motor horn sounded and a battered old Ford shook its ancient bones round the corner. It was the Chiddenham "sedan." driven by the Squire—Nelson"s silent father.

THE "sedan" stopped with a squeal and a squirm as the Squire saw his youngest—and, secretly, his favourite—son. Squire Chiddenham was running across to have a chat with Sir Milner Bayliss, the insurance millionaire, an old crony of the Squire and a great friend of Nelson, His grey eyes soaked up Nelson.

"Anything wrong. Nelson? You look—worried."

"Yes, sir. I've had a queerish thing happen."

The Squire glanced at his watch.

"Well, well, hop up and tell me as we go."

So Nelson and Red "hopped up," and long before he had confided fully in his father they had rattled up to Longwater Hall

"Better come in with me and we'll get Sir Milner into consultation—three heads are better than two," said the Squire.

So it was in the presence of his father and the childless man who wished he were his father that Nelson presently ended the tale—tremendously glad and relieved that great good luck had ordained things so,

"Hum!! said Sir Milner at the end, eyeing Nelson under grey, shaggy brows. "It's a queer Story, my boy—hey, Chiddenham? Captain Ken of all men—God bless my soul, what a tragic thing! What were you planning to do about it, Nelson?"

"Well, sir; I don't know—quite. I wondered on the way home it Captain Ken had quite got hold of the truth—about that lap-dog in the first place," said he diffidently.

"Well?"

"You see, I know, of course, that ladies do—well kiss and fondle dogs that are not really broke—"

"Dirty little dogs, in fact," suggested Sir Milner, dryly.

"Well, sometimes, sir. But all the same, I've never heard of a diseased or dirty dog killing anybody," declared Nelson. "After all, sir, he may be wrong."

"It's more of a question for a doctor, that," suggested the Squire.

Nelson seized on that.

"Yes, father—that's exactly it. That's what I thought. And I was thinking that if somebody went and called on the doctor that attended the lady who died, and explained the trouble with Captain Ken—how he isn't to be trusted about lap-dogs— perhaps the doctor might be able to do something to help him."

Both men nodded, deeply interested.

"He might be able to prove that the poor girl died of something which had nothing at all to do with contagion or infection from one of her toy dogs—that's what you mean, hey. Nelson? Well, that's a good idea—very sound—very well thought out. Don't you agree, Chiddenham?" boomed Sir Milner.

The Squire nodded.

"D'ye know the doctor's address?"

"Oh, yes, sir." said Nelson. "Miss Pallis, who is a cousin of Miss Seymore, the girl who died, told me the village she lived in"—he named it, a place some fifteen miles away—"and if the doctor there is the same, he would be the one who attended her."

Sir Milner agreed.

"Yes, that should be so, Nelson."

He touched a bell

"And, if your father is willing, I think it would be about the best thing possible if I let Chater run you over there to have a chat with that doctor and hear what he has to say. Have something to eat here first, then nip over, see what you make of it—tell him your story just as you've told us—and then come back here and have a bite of dinner, and let us know just how you got on. Hey, Chiddenham—what d'ye think?"

The Squire did not make haste to answer, He bad seen Nelson flinch a little—and he was not quite sure if the boy was equal to the task.

"Let the boy go, Chiddenham. We all have to begin to learn about life some time or other, said Sir Milner.

The Squire shrugged.

"All right. Do the best you can, Nelson. Tell your story—"

"In your own way, mind," interposed Sir Milner. hastily. "Just as you've told us."

A few minutes later Master Nelson Rodney Drake Chiddenham was sitting curled up in a corner of the huge Rolls limousine en route to the village in which Miss Seymore had lived—and died.

There was no difficulty about finding the doctor—a tall gaunt man of sixty of rather severe aspect, but with a twinkle never very far from his eyes and a wide mouth that smiled quite readily. His name was Forbes. He was just entering his house as the great silver-grey car rolled up and Nelson emerged.

Nelson raised his cap and introduced himself.

"Chiddenham—Chiddenham!" mused tho doctor. "I know your father—I met him some years ago at u shooting party at Longwater Hall Come in! Nothing much wrong with you, I should think."

His keen eyes flickered over the iron cage embracing Nelson's leg.

"I'm just having some tea—you'd better have a cup with me. Is that your father's car?"

"No, sir. It belongs to Sir Milner Bayliss. He, sent me over in it."

So they went indoors. Nelson found it quite simple to tell his story to the doctor, for he proved to be an easy man to tell things to. He listened carefully and rarely interrupted.

He asked a few questions at the end, then sat thinking for a few moments. He got up and went to a sort of bookcase and brought out an oldish, well-worn book. rather like a thick diary. He pored in silence over an entry in this book for a time, his face serious.

"Yes, yes—poor girl. Remember the case perfectly," he said to himself, and closed the book. "Humph!"

He thrust out his lower Up and studied Nelson with absent eyes.

"All this—all this is very unprofessional, Nelson. Yes. But desperate cases—desperate remedies, eh? Perhaps not so desperate after all. More tea, Nelson? No. Then just hang on here for a few minutes, will you? I have one or two things to see to, and then I think I will run over and see Captain Kennedy in my private capacity, of course. He went out.

A quarter of an hour later the Rolls was suavely conveying them back to Sir Milner's.

"You seem to know a pretty good deal about dogs, Nelson," said Dr. Forbes presently. "Did you ever hear of a case where a toy dog—or a cat—infected its owner—fatally?"

"No, sir," said Nelson, flatly, accustomed as he was to unkissed dogs.

The doctor lit, with the care of a man who cannot afford to spoil it, a cigar.

"Miss Pallis—he said presently. " As I remember her, she was very much like Miss Seymore—"

He thought for a while in a cigarry silence.

"I suppose it would be entirely feasible if we diverted this rather sumptuous vehicle sufficiently out of its course to enable us to call on Miss Pallis before we settle down on Sir Milner?" he said at last.

"Yes, sir," said Nelson, blithely enough.

The hard-working country practitioner spared an odd glance out of an eye-corner at the shabby boy who so casually and unconsciously directed the voyage of a machine almost as expensive—so to put it —as small torpedo-boat.

Another cigar-flavoured pause. Then the doctor said:—

"What's wrong with your leg, my boy? Does it hurt?"

The leg kept them comfortably conversational till the car ran in through the green gate of Miss Pallis, and slid silkily to a standstill opposite her front door.

There the doctor left Nelson to himself

PRESENTLY the front door opened and the doctor stepped in again. He was followed by Miss Pallis.

"Ah, Nelson—is that you?" she with a voice that made him want to go out and, for her sake, invite Red to bite a large piece out of some villain somewhere. Only the parish was short of villains.

The car was further diverted—by the curiously authoritative voice of the old doctor—to Hartsford Hall.

It was a long wait there—very long.

Yet. in the end. three people appeared—the doctor, Miss Pallis, and Captain Ken.

It seemed a little odd to Nelson that the Captain saw Miss Pallis into the car without a word—without one word. As for himself—h« might have been a speck of dust in one of the broad brake drums of the car for all the notice Captain Ken took of him.

Yet he was curiously content as the car rolled away. He seemed to sense that the Captain could not have spoken without tears. He had looked like a greatly shaken man.

It was fairly obvious in the well-lighted back of the car that Miss Pallis had been crying. But, unless they must, wise folk don't notice when ladies cry—though they are most observant when ladies laugh.

It was the doctor who broke the silence.

"Well, so ends a perfectly understandable misapprehension," he said.

"Yes," said Miss Pallis rather faintly. But her eyes shone.

She said nothing more until the cur was at her house. Then she shook hands with the doctor, and suddenly leaned towards Nelson.

"Good night, Nelson," she said. Her hair was like silver and gold intermingled in the subdued light, and her eyes were like jewels set in dark shadows. "I am so glad I met you on the downs—so grateful!"

Except for his mother's, Nelson had never known a woman's arms about him before.

The doctor coughed dryly as the car encircled the oval of turf and turned homewards.

"Ladies," he said, "are apt to be a bit demonstrative, Nelson. Otherwise all's well. It was an odd delusion, that of Captain Kennedy's. Miss Seymore died of a form of erysipalas. Nothing to do with the dogs—nothing at all!"

Only a practitioner of his own quality would have known that he uttered the thing which was not.

"I was able to convince Captain Kennedy of that—in the end."

Nelson thought.

"But wherever did he set the idea from—firs of all, I mean, sir?" he asked.

The doctor laughed—one of those reassuring laughs that doctors use.

"Why, from the idle, foolish burblings of an old gamekeeper of the Seymores. An old hoy—dead years ago—who hated everything except a steady retriever. He said—that poor old ignoramus—to Captain Kennedy that in his opinion Miss Seymore had been infected and killed by lap-dogs! And that, magnified by war-wrecked nerves, war-strained mentality, wounds, and shell-shock, sowed a dangerous seed in the Captain s brain, Nelson! You saw the fruit of that seed."

Nelson thought again.

"Yes... but Miss Pallis, sir? I can't see how she—"

The doctor laughed quietly.

"No? No. It just happened that she was always rather fond of the Captain. And she bought a place near the place he had inherited—to be near him, you see, Nelson. She had a companion—and the companion had a rather noisy Peke which attracted the lethal attention of the Captain. In a way it was all pure chance—coincidence, if you like the word better. And in a way it was the mercy of God.

"To-night—back there—Miss Pallis came to the Captain like the lovely phantom of the poor girl who many years ago might have been his bride! He—she—they were both grateful, I think, to come together again. You see, Miss Pallis and Captain Kennedy were very close friends indeed—until Miss Seymore came home, met him, and swept him off his feet. And also Miss Pallis is extremely like her cousin—not quite so lovely, perhaps, say a very sweet echo of that most beautiful girl who died. But the Captain, after all, is only an echo—so to put it—of the man he used to be.... That is, in a way, good. Miss Pallis has always loved him. That is really why, when she heard that he had returned to England—he went abroad when Miss Seymore died, ten years ago—and had settled down here, she, too, came here to live—to renew, if possible, that old friendship. They will comfort each other, these two. my boy."

The old doctor chuckled.

"Not such cold comfort either—they are still comparatively young, well-off, and I think the lap-dog complex will soon be exorcised, if it isn't already! Not so bad, Nelson. All will be well with them!"

Before Nelson had quite made up his mind what "exorcised" meant the car stopped and his father and Sir Milner appeared in the great ball.

THE doctor, on old acquaintance of Sir Milner and the Squire, may have been just a little "unprofessional" during the story he told them at dinner, but one forgives that when the last words are "So, you see, all will be well with them."

Then Nelson was called upon to give again his version of the matter, which he did, not without embarrassment.

Sir Milner eyed him.

"So, really, you set out with old Red to track down those rewards hey, Nelson?" he asked.

"Well, yes, sir," admitted Nelson, a little fiery in the face, and added hastily and rather emphatically that be would not dream of attempting to collect them now.

"Of course not. Its just a bit of bad luck, Nelson. But that's the way of the world—the way of the world, my boy. Never mind—one has to take the thick with the thin. And you've helped make those two folk happy—a good chap like Captain Ken, a charming lady like Miss Pallis. That's something. Satisfied?"

"Yes, sir," said Nelson and meant it

He and Red went home with the Squire in the ancient "sedan."

"Tired, Nelson?" asked his father, half-way home.

"No, father."

"Good. Yon did very well about all that, Nelson. He's a good chap, Captain Ken. It would have been a great pity to have had a scandal. You weren't upset at losing those rewards?"

"No, sir—not a bit. I—I like Captain Ken and Miss Pallis."

"Good," said the Squire, and honked the old sedan into their drive.

"Hah!" said Aug humorously as Nelson entered into the family. "And what might our Mister Sherlock Holmes have achieved during this long session with the Hound of the Bustervilles?"

(Fair Aug, having just failed to borrow "ten modest bob" from sister Ella, the family miser, was a little annoyed at him.)

Nelson grinned

"Nothing, Aug," he said, cheerfully enough

Aug affected extreme astonishment.

"What—no rewards! The old bloodhound must be losing his olfactory genius!"

The Squire entered. He had heard Aug and he was smiling one of his rather rare smiles.

"Oh. about those rewards. Nelson," he said before the whole family, and took a cluster or bank-notes from his pocket. "Sir Milner insisted on making an arrangement about those, and he is himself adjusting things with—with—the right man—later He insisted. Let me see now—Lady Downsmore offered twenty-five pounds, didn't he

Slowly he put down on the table one by one five most attractive five-pound notes.

"Lady Downsmore's reward!" he said.

The family gaped. He added a fiver.

"Mrs. Morehouse's reward."

Aug gasped. His father added yet two more fivers.

"Mrs. Tollemache's reward. That correct, Nelson? Count the money"

Nelson counted eight five-pound notes.

"That's right, sir," be gulped.

"Well, it's yours, my boy—well-earned," said his father, took a quick glance at him. and went on:-

"Sir Milner will arrange with those ladies and—our other friend! Also—"

The Squire produced ten more or those fivers. Aug reeled.

"He says that the pet-dogs of those ladies must be replaced. And as he considers that you know more about dogs than any body in the district he wants you to find three Pekes, or whatever they are that please the ladies. They are to take their pick. You are to find 'em. If you can buy them for less than fifty pounds you can keep the difference. If you can't, Sir Milner said—then you aren't the boy he thought you were!"

The Squire pushed over the notes and left Nelson—and all—staring at forty pounds of Nelson's money... maybe more.

The long, low, liquid whistle of the totally be-staggered Aug fluted like the far cry of a hungry gull through the big room. Nelson looked at his father, serious and quiet, opposite him. and, for no reason that he understood, something seemed to swell in his heart and his throat—something that threatened either suffocation or a dreadful, shameful spate of tears.

Half blindly, he pushed the pile of notes towards his mother and, muttering something almost unintelligible about supper for Red, limped hurriedly out of the room.

There was an odd pause, broken by the voice of the Squire—the voice that meant strict business

"And if anybody here tries to cadge any of that money from Nelson and I hear of it, there will be trouble!"

But the genial August "touched" quite successfully for what he called a couple of "half bars," viz., one pound, behind the stable three days later. And the Squire never heard of that for even Aug had a sort of dim idea that he could trust young Nelse to that extent.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.