RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

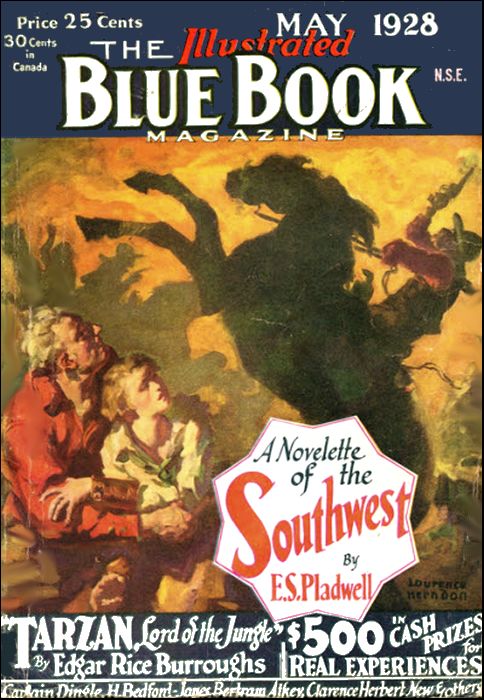

The Blue Book Magazine, May 1928, with "Miss Brown's Jewels"

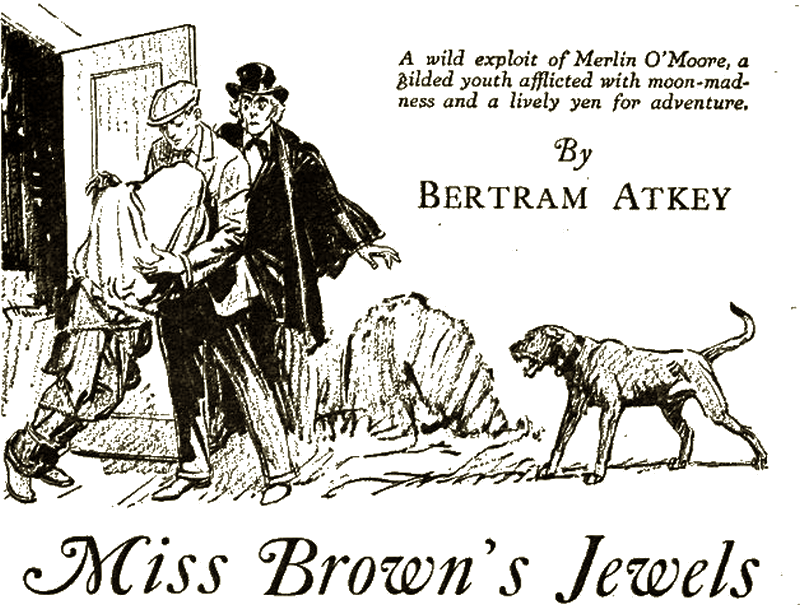

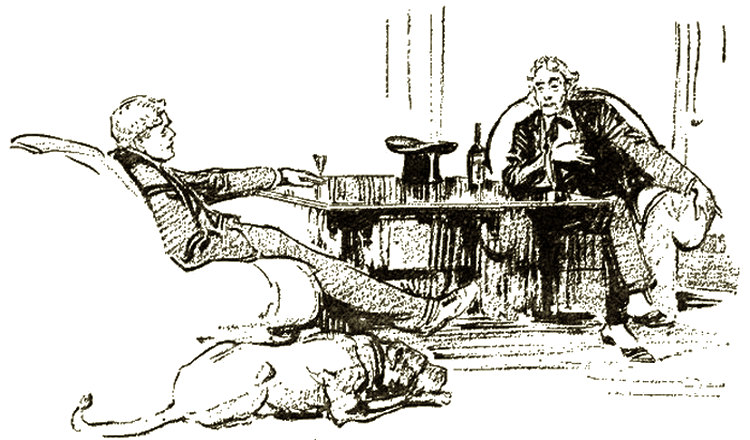

MR. MERLIN O'MOORE. of the Astoritz Hotel lit a fresh cigarette and lounged back on the big couch preparatory to enjoying a liqueur after dinner.

"Touch the bell, Molo," he said restfully, watching the smoke from his cigarette as it swam lazily upward.

Molossus, the big dogue de Bordeaux, rose and slouched heavily to a bell-push, against which he leaned his fearsome, wrinkled head for a moment. Then he padded back to his place near Merlin, curled up on a rug, and with pale eyes watched the door.

Hardly had the dogue settled comfortably down before the door opened quietly and Mr. Fin MacBatt, Merlin's lank, big-headed, blue-jowled valet, entered.

"You rang, sir?" inquired MacBatt, eying them with his curious air of sardonic deference.

"I did, MacBatt!" said Merlin. "You have something to say to me, I believe—if I correctly interpreted the somewhat muffled, remotely sullen remark you made as I came in from dinner."

Mr. MacBatt looked a little less gloomy, and even managed to infuse into his eyes a certain expression of friendliness as his gaze dropped to his arch-enemy Molossus, who, looking like a nightmare carved in fawn-colored iron, was regarding the valet intently.

"Yes, thank you, sir; I did wish to put a small matter to you, if you've no objection, sir," responded Mr. MacBatt.

"Very well—go ahead."

The gloomy-visaged MacBatt gave an excellent imitation of a nervous smile.

"The fact is, sir, I'm thinking of getting married," he said, and paused to note the effect of this statement upon his employer. There was no effect; none whatever.

"What has that to do with me, my dear MacBatt?" asked Merlin suavely.

THE valet's smile vanished and his hard eyes hardened still more.

"Well, sir—if I may say so, sir—you were good enough once to promise me—so to put it, sir—a present when I eventually married, if you remember the remark, sir."

"True, MacBatt. I remember it perfectly. And this is the fifth time you have tried to extract that present from me. It seems to me that you are a very fickle-minded young person, MacBatt. And I seem to remember that at the same time I added to that promise a stipulation that I should approve of the lady of your choice."

"Oh, yes, certainly, sir. I remember perfectly," said MacBatt, with a rather wolfish grin.

"Since that time you have enlisted the aid of no fewer than five fair ladies in five desperate attempts to separate me from that present."

"Five, sir!" MacBatt's voice was one of admirably feigned incredulity.

"Even five," said Merlin gravely. "There was the half-caste girl who was maid to the wife of that Portuguese from South America staying in this hotel last year; there was the hawk-faced French lady of uncertain age and disposition introduced to you by Henri, the head-waiter of the Mediaeval Hall; there was that simple-looking country girl from Gloucester, with the complexion of a dairymaid and the soul of a Russian she-wolf; there was that needle-witted lassie from Leith; and that buxom widow who kept the riverside hotel which required a little more capital.

"Who is the lady on this occasion, MacBatt? And what percentage of the plunder does she expect to get?" continued the multimillionaire playfully.

"The young lady is connected—in a way—with the stage, sir," replied MacBatt dourly.

Merlin showed a little more interest. His best friend also was connected with the stage—being, indeed, none other than Miss Blackberry Brown, the famous white-black comedienne.

"Yes? What does she do?" he queried.

"She's Miss Blackberry Brown's assistant dresser, sir," said MacBatt rather triumphantly. "And it's genuine love this time, sir."

"What is her name?"

"Dora Downton, sir."

"T see. And you and she are in love?"

"Undoubtedly, sir."

"And want to marry and take an inn?"

"Certainly, sir; a café—not an inn, sir."

"Very well. I'll think it over and—"

AN electric bell whirred somewhere in the suite. MacBatt excused himself and hurried to the door.

Merlin smiled as the big-head went. "MacBatt has been having a bad time at poker with Henri and Company recently, Molo," he said to the dogue, "and he wants some ready money."

MACBATT, opening the door, found himself face to face with a gentleman of medium height, with a very thin, very pale, clean-shaven face and a head of silvery-white hair. He wore a very ancient but rather racy-looking, curly-brimmed silk hat, and an equally ancient, deep-caped Inverness overcoat which had faded from black to blackish green. He looked like an actor retired from the stage, to live upon his wits.

"I desire to speak with Mr. Merlin O'Moore," said the man in the Inverness, in a voice of singular sweetness. "Do me the courteous favor, therefore, to convey to him the information that Mr. Fitz-Percy—the bearer of an important message from none other than the world-famous Miss Blackberry Brown—awaits his good pleasure."

The saturnine MacBatt surveyed him in silence while he spoke. Then, infusing into his tone a touch of respect which had not been in his attitude when he first opened the door (inspired, doubtless, by the mention of his master's great friend, Miss Blackberry Brown, the famous white-black comedienne), he invited the caller to enter.

"Here's one of the smooth ones," muttered the valet, as he moved away to advise Merlin of the call. "Yes, one of the deadheads—or I'm a Mormon!"

Merlin O'Moore received the ancient deadhead with the affability of a man who feels lonely.

"If you do not mind talking while I drink a liqueur, Mr. Fitz-Percy, I should be glad to hear of any way in which I can be of service to you or Miss Brown," he said politely.

"Assuredly I do not, my dear sir," returned the Fitz-Percy, running an eye, undimmed by age or usage, over the tray. "Indeed, speaking of liqueurs, I may say that I have not yet taken my liqueur this evening. Absurd though it may seem to you, who probably have never been in such a fix in your life, I am confronted with such an alarming deficit in my—er—personal budget—that I had decided to postpone liqueuring until some other day."

He smiled blandly at Merlin, his hand absently straying to the back of a chair, delicately indicative of his willingness and preparedness to draw out that chair and occupy it. Merlin did the correct thing, from the Fitz-Percy's point of view—he invited his caller to join him—an invitation which was swiftly accepted.

"To take a liqueur with the famous Mr. Merlin O'Moore at the equally famous Astoritz is a privilege which few intelligent people would decline," said the Fitz-Percy, with a graceful little how. He handed his coat and hat to MacBatt.

"Bestow them carefully, my good friend," said the deadhead, "for they have seen much honorable service and deserve careful and considerate handling in their declining years."

He sat down, with something in his air which suggested that he did not propose to rise again with undue precipitation.

"YOU are a friend of Miss Blackberry Brown?" inquired Merlin.

"I trust that I may truthfully say so," replied the deadhead. "I taught the child many things appertaining to her art. Her mother was a close friend of mine years ago, years ago—in the palmy days. I think the little one would be the first to claim me as a friend, and, at risk of laying myself open to the charge of vanity, I believe the child has yet a soft spot in her great heart for old Fitz-Percy."

"I am sure of it," murmured Merlin politely, though he had never heard Miss Brown mention this old family friend before.

"And I am proud to think that, desiring an utterly reliable messenger to you this evening, she did not hesitate to pour her troubles into the ever-sympathetic ear of this old battered one whom you see before you."

"Quite so," replied Merlin. "And what precisely was it she wanted done?"

The deadhead leisurely finished his liqueur.

"She wishes you—and if you care to avail yourself of my services, myself also—to take steps this evening to prevent, if possible, a particularly sordid robbery," he said calmly.

Mr. O'Moore sat up.

"Robbery!"

"Yes, indeed—a very bad and heartless case," said the Fitz-Percy tranquilly. "Miss Blackberry has just discovered that, early this evening, her assistant dresser, one Dora Downton, skipped gracefully into the never-never—taking with her a handful of Miss Blackberry's very best jewelry!"

MacBatt, hovering at the sideboard, flushed a blue-black flush, and broke in urgently:

"Is that true, sir?" he demanded.

"If, my good friend, you will telephone to Miss Brown's dresser at the Paliseum, she will confirm it," Fitz-Percy replied.

The glowering big-head turned to Merlin.

"The wedding's off, sir!" he said, curtly, and slid out of the room.

Outside the door he ground his teeth and shook his fist.

"Laugh!" he snarled. "That's it—laugh! This is the sixth go I've had for that wedding present; but watch out for the seventh, my laddie! Next time I try I'll get it—if I have to go through it and get married before I call on you for the coin!"

"IS that really so?" Merlin was meanwhile asking of the deadhead. Fitz-Percy nodded.

"Yes, indeed," he said. "It is that which I came round to see you about. Let me explain: This afternoon I had hoped to enjoy the privilege of inviting Miss Blackberry to take tea with me. Indeed, I invited her yesterday. Singularly enough, the approach of the tea-hour today discovered me completely—er—without funds. An embarrassing position, you will agree, my dear boy—most embarrassing—to one less accustomed than myself to such a difficult situation. Fortunately, I have acquired, in the course of an abnormally checkered career, a certain deftness in the art of grappling with such situations; so, borrowing a nimble twopence from a sympathetic landlady, I merely telephoned Miss Blackberry and pleaded neuralgia. It was when I called in at the Paliseum this evening to explain the matter in detail that I discovered the child and her head dresser mingling their tears. Shocked, nay, stunned, my dear boy, I comforted them and asked what trouble had befallen them. So I gleaned the news. The Downton girl seems to have made a clean sweep. That poor child's jewels were in a green leather case with a number of letters she valued. The Downton had taken case and all—"

Mr. O'Moore moved uneasily.

"Letters?" be inquired. "What letters?"

The huge dogue hunched near the couch pricked his cropped ears slightly at Merlin's tone. Was there or was there not a slight jar of jealousy in the millionaire's voice? But whatever Molossus' opinion may have been, the deadhead showed no sign of having observed it.

"The letters, my dear boy? Oh, I don't know. Evidently some which she valued," he replied carelessly. He knew well enough—none better—that Merlin was in love with Blackberry Brown, and that the letters were from him, but he preferred that Merlin should discover the fact for himself.

"The letters, my dear boy? Oh, evidently some which she valued."

He turned, pointing through the big window.

"What do you say to our sallying out in search of the deft-fingered Downton, and recapturing the jewels and letters? It is a night after any adventurer's heart—believe me, there is a moon as big as a barn rising—and who knows but that we may achieve yet another success?"

Merlin slid off the couch.

"Certainly," he said he; "ring for Fin." And he disappeared into his bedroom, whence a second or so later MacBatt followed him.

Mr. Fitz-Percy, left to himself, smiled, nodded, finished his liqueur, refilled, and began to pace the room.

"Curious, very curious, that the valet should have selected as his latest bride-to-be this light-fingered lady," he mused. "We must inquire into that aspect of the case—yes, indeed!"

He then proceeded to inquire into the aspect of his cigarette-case which, being empty, he filled with some of his patron's admirable cigarettes—frankly praising the millionaire's taste in tobacco, the while.

A QUARTER of an hour later the millionaire, the deadhead and the dogue had departed in search of the delightful Dora and what Dora had so expertly got away with.

Having seen his employer well away, the valet mixed himself the stimulant he considered he needed, and settled down sullenly to review the situation.

"If anyone asks my opinion," he said to himself, "I should say that it serves 'em damned well right; Here Blackberry Brown—earning more money for singing a few songs and doing a white-black dance every night, than she knows how to spend, and owning so much jewelry what with the things the Boss gives her, that if she put it all on she'd have to use crutches to help her carry it—goes and leaves a box full of it lying about in her dressing-room to tempt a poor little kid that's as much stuck on Mr. O'Moore's valet as her missus is on Mr. O'Moore! Can you wonder that Dora does a bunk with the box? I can't! We may be 'umble, but damn it, we're 'uman—me and Dora." He took a pull at his glass—and suddenly recalled that this was his night "off" and that he had an appointment to meet the doubtful Dora at nine o'clock.

He stood up sharply,

"Of course I don't suppose for a minute that she'll be there," he reflected. "She's vanished for good—if she's the girl I take her for. But—well, he wont be back for hours yet, and I might as well have a look around. After all, I don't know. Put it this way—supposing the girl's so much m love with me,"—he glanced at himself in the glass,—"that she's simply pinched the jewels so that she can bring a sort of dowry to me—though I must say that Dora never struck me as being the sort of girl likely to get bats in her belfry over anybody but Dora Downton. Still—while I aint any curly-wooled matinée idol, I aint so bad! I may look a bit tough, perhaps, but lots of women like a tough-looking man. Anyhow, I'll have a look around. May as well see how the land lies."

DULY dressed, and merely pausing for one swift "one" with Henri (on the hotel) as he passed the Mediaeval Hall, MacBatt, dreaming all sorts of complex and idle dreams regarding dowries and the like, presently arrived at a retired little underground grot and wine-bar which was the usual trysting-place of himself and Dora. Taking a chair behind a discreet screen in a discreet corner, the big-head beckoned Giuseppe, the waiter—more usually known to his clientele as "Gus."

Gus, it seemed, had news for him,

"I beena look-a-out for you. Mistera MacaBatta, yaes," he said. "Thees message come at commencementa of evening today." He passed a crumpled note. MacBatt tore it open and, as he half-expected, discovered it to be a line from Miss Downton explaining that she had been detained and asking him to call for her at an address which she gave.

MacBatt countermanded the refreshment be had ordered.

"Leave it, Gus," he said. "I'm in a hurry."

Gus grinned and accepted a shilling. "That is all raighta," he said. "Thees—"

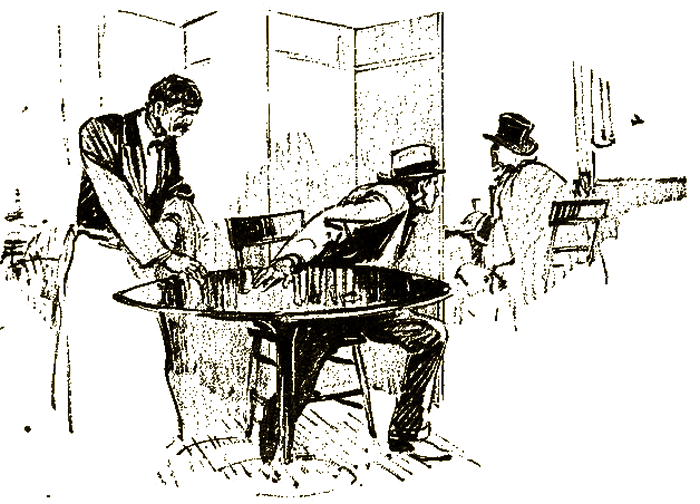

He stopped short, staring round as the big-head ducked violently behind the screen, obviously to escape the notice of two newcomers who were descending the stairs—none other than Merlin O'Moore and the Fitz-Percy. They proceeded to occupy a table at the other end of the room, and MacBatt beckoned Gus back.

"Look here, Gus, I don't want those two men to see me here—understand? Go across and keep them occupied till I'm out of it."

"Look here, Gus, I don't want those two men to see me here—understand?"

The ever-obliging Gus nodded.

"Rely-a upon me, Mistera MacaBatta!" he said reassuringly, and hastened to attend the others.

"That's what I like about old Gus," mused MacBatt, watching cautiously. "You can rely on him. He's a good little Italiano, is Gus."

Then, observing that the wily Neapolitan had succeeded in drawing the attention of both Merlin and the deadhead to something interesting in the wine-list, MacBatt, shielding his face with a handkerchief, slid swiftly upstairs and out.

"Good business," he said, with a sort of sardonic satisfaction, surveying Merlin's car waiting outside; and hailing a passing taxi, he ordered the licensed brigand at the wheel to drive to an address near Putney—the address given in the note from Miss Downton

But MacBatt was not the only one who had been busy since the deadhead had broken the sad news concerning the deft-fingered Dora. Messieurs O'Moore and Fitz-Percy, for instance, had permitted no vegetation to flourish beneath their motor-tires. They had interviewed pretty Miss Brown between "turns" at the Paliseum and the Colladium Theaters of Variety, and while Merlin had soothed and comforted her, the wily Mr. Fitz-Percy made inquiries among those most likely to know—Blackberry's other dresser, the stage doorkeeper, and so forth—and had gleaned a few suggestions as to Miss Downton's haunts.

A quick, though fruitless, run through several of these had finally landed them at the retired little wine-vault from which their inopportune arrival had speeded the sardonic MacBatt.

They proceeded to make further inquiries—this time of the reliable Gus. That "reliable" individual, who was an extremely shrewd judge not of character but of the depth of a customer's pocket and the probable extent of his generosity, speedily realized that he had to do with men of means. The careless way in which Merlin allowed the deadhead to order a bottle of the most absurdly expensive vintage in the vault, and especially the offhand way in which Merlin ignored the wine when Gus had reverently poured it, convinced the waiter of that.

So when presently the deadhead suggested tentatively that possibly Gus could tell them whether a young lady—here he described Miss Downton in detail—had been in, or was likely to be in, that evening, the reliable Gus, with a swiftness and accuracy that would have staggered MacBatt, proceeded to tell all he knew (and a good deal that he did not know) about the fair Dora and her customary cavalier, "Mistera MacaBatta."

"And where, my good young fellow, do you think Miss Downton may be found now?" suavely inquired the deadhead, exchanging glances with Merlin.

Gus did not know—at least, he said he thought he did not know. It was so difficult to remember. He was a busy man—as the signors could see for themselves. He was also a poor man, and had to work so very hard to make a little money, that he could not always remember things.

Merlin understood, and without delay he put a sovereign on the table.

"Can you remember if I give you this?" he asked.

Gus could. Promptly he reeled off the address he had read over MacBatt's shoulder when the valet had looked at Miss Downton's note and, sliding the sovereign expertly into his pocket, he unblushingly gave them full details of the circumstances in which he had learned the address, including a brief description of the big-head's hasty flight and adding that, in his opinion, arrived at after a careful study of the couple extending over some weeks, the delightful Dora loved the dour MacBatt about as much as she loved work.

MERLIN and his hawk-witted old companion were well on their way to Putney before the deadhead voiced a doubt which had been with him ever since they left the wine-bar.

"What, my dear boy, are your view about the honesty of the good MacBatt?" he inquired.

Merlin's views were caustic, and soon expressed.

"He's much too shrewd to steal or help steal anything from me or my friends on a small scale. If he could get away with an amount that would keep him in complete comfort for the rest of his life, he would. But not for less," said the millionaire. "I would trust him with five hundred or a thousand pounds in cash, but I should be extremely unwise to do so with ten thousand."

"Judging from my own short experience of Mr. MacBatt, I am in complete agreement with you," said the deadhead thoughtfully. "And therefore it is difficult to understand why he has deliberately gone to visit the doubtful Dora—knowing her to be a candidate for Holloway Prison."

"Perhaps," said Merlin sarcastically, "he loves her so much that his emotions have drowned his prudence."

Fitz-Percy laughed.

"Is that quite like MacBatt, my dear boy?" he asked incredulously. "However, we shall soon see. It may be that he will have a perfect reason." He looked up at the bulging yellow moon. "At any rate, he and his lady, between them, have given you an object upon which to work off your moon-restlessness (which Miss Blackberry Brown tells me you share with her) this very charming evening."

Merlin nodded as they slid over the bridge, and pulled up so that they could inquire from an adjacent policeman the whereabouts of the place they sought.

They had not long to seek—within ten minutes of crossing the bridge they had arrived in a quiet, lane-like by-road, badly lighted, and sparsely built upon; and they stopped some thirty yards from a house which, surrounded by trees and shrubs, lay well back from the road.

There were no lights visible in this house, and they approached it very quietly, with Molossus at heel. They entered the gate, passed along a short drive and found themselves at the front door. Here Merlin paused, sniffing.

What is it, laddie?" whispered Fitz-Percy.

"Petrol. Somebody has poured or spilled some petrol near here within the last quarter of an hour or so. The smell doesn't hang about long out in the open. They may have gone, after all. Probably the fair Dora, or her companions, if any, poured some petrol into their tank,"—he pointed to the tracks of motor-wheels, plain in the moonlight.—"and upset some as they poured it. If so, they haven't been gone long, but it looks as if we have just missed—"

He broke off abruptly as a huge black Chow dog came dashing round the corner of the house, snarling rabidly.

Merlin released Molossus, and the black dog saw, too late, what it had thoughtlessly charged into. It never had a chance. There was a hideous snarling flurry, one keen yelp choked off halfway, and then the pale-eyed dogue brought the chow back to Merlin, very much as a retriever brings a rabbit back to a keeper.

There was no sign from the house.

THEY reconnoitered completely round the place, without discovering a light in any window or hearing a sound of any occupant. So they broke in through a window at the back, and scouted swiftly through the house behind a big electric torch. A smell of cigar-smoke still hung in the atmosphere, but it seemed the birds were flown or not at home.

"They're gone," said Merlin, while in one of the front sitting-rooms.

"Ar-rrgh!" remarked somebody or something from a big wardrobe-like cabinet in a corner.

Molossus wheeled to it, sniffing and snarling softly about it. The deadhead turned the key and swung back the door.

Something with a canvas bag over its head and so swathed in box-cord that it looked like a mummy, fell helplessly forward into the arms of the explorer.

But it was not a mummy—it was merely Mr. MacBatt, bound, gagged and bagged, with two red eyes that would shortly be black and a lump upon his bulging brow the size and shape of a large gherkin.

They unpacked him—and considerably to their relief found that he was conscious. At any rate, he spoke.

"Brandy," he said curtly.

Gently they broke it to him that there was none.

"Whisky, then," he said, groping for the flask Merlin offered him. He drew heavily upon it—very heavily indeed. But it did him good. It cleared his head. He stared for a moment, then hastily ran through his pockets.

"They've got my keys, sir," he said. "What's the time?"

"Nearly eleven o'clock," Merlin replied.

"Then I've been in the box there twenty minutes and they've been gone nearly a quarter of an hour. Have you got the car, sir?"

Merlin nodded. The badly jarred big-head exclaimed: "Then we'd better follow them, sir. They mean to break into the Stores and fair strip the place!"

They understood then, and a second later were making a rush for the car.

AS has been explained heretofore, the millionaire practically owned, among other things, a huge departmental store near Oxford Circus. Since he occasionally needed things from this highly convenient piece of property, and was in the habit of sending MacBatt to get them, day or night, the bulbous-browed valet was supplied with a master-key for use at night. Anything Merlin needed from the Stores, therefore, no matter at what hour of the night, was always obtainable by the simple process of sending MacBatt to take it, leaving a signed chit either with the watchman or in place of the articles taken, to be discovered and charged to Merlin by the assistants in the morning.

Now, it appeared that Miss Dora Downton, who presumably knew of this arrangement, and her friends—two leather-hided, rubber-souled gentlemen, being her brother and her real fiancé, explained MacBatt—were about to visit the store, enter by means of the valet's key, sandbag the watchman, and practically devastate the jewelry department at their leisure.

The successful ravishing of Miss Blackberry Brown's jewels, it seemed, had merely been a preliminary canter, so to speak, to the real effort.

"I see," said Merlin as he switched on his engine. "We ought to arrive just at the most useful moment."

He started the car and MacBatt lay back to reflect upon his present situation and con over the story which, later on, he purposed to present to his employer.

MacBatt seriously considered that he had been shamefully treated.

He had followed Miss Downton on to Putney with some vague idea that she was so very much in love with him that she had stolen Blackberry Brown's jewels with the intention of investing the proceeds in some way (unknown to and unguessed at by the cadaverous big-head) which might benefit him as well as herself.

This intention would not be at all honest, of course. But, then, neither was Mr. MacBatt, and, in any case, he proposed to explain to Merlin that the reason he had followed Miss Downton was because he hoped to show her the error of her ways, get the jewels back and restore them to Merlin's little friend, Blackberry Brown. It was a good reason and looked sound to MacBatt—be did not see how Mr. O'Moore was going to deny it.

Immensely to his amazement, however, his dream had been finished with extraordinary swiftness—practically, indeed, at the moment he had entered the drawing-room of the Putney house, to which he had been admitted by a deep-jawed, tight-lipped young man who was a stranger to him.

"Ah—you're the MacBatt man?" that individual had said, "We're expecting you. Dora wants to see you; step right in—yes, she's in there." He had indicated the drawing-room. "Step right in!"

And the unsuspecting MacBatt had stepped "right in"—right into a slam across his bulging brow with a sandbag that felled him like a poleaxed mule.

HE did not entirely lose consciousness. Indeed he retained just enough sense to feign unconsciousness, and so was dimly aware of fluttering fingers that searched his pockets for his keys, and presently found them, and of voices discussing the raid upon the store which was to follow the successful theft of the keys. Then the valet had felt himself bound, gagged, bagged and put away where Merlin and the deadhead had found him.

Yes, on the whole, reflected MacBatt, he was satisfied. As the thing would appear to Merlin and Blackberry, he had endeavored to recover the jewels and nearly lost his life an his heroic attempt. That was good enough. If Blackberry—and possibly Merlin also—did not do something pretty tolerable in the reward line, MacBatt would be somewhat seriously disappointed in them. And as for the delightful Dora and her brace of man-eaters—well, he had not yet finished with them. The big-head tenderly fingered the lump on his brow and with a dour ferocity began to gloat over the coming attack upon the looters at the store....

But—and it was perhaps as well for the Downton trio—Mr. MacBatt was not invited to contribute his personal views towards the strategy which Merlin and the deadhead purposed using to ensnare the looters, and consequently the whole thing went through with such simplicity and complete success that there was practically no need whatever for physical force.

Running slowly through a thoroughfare of clubs and restaurants, Merlin picked up two hefty naval officers, friends of his on leave, who were "looking round" the livelier parts of London for whatever might be visible; a little farther on near the Astoritz, he took aboard an inspector of police and a hugeous Irish constable, also friends of his. Then he turned the heavily laden car store-ward.

They left the constable in charge of the small but good three-seater motor of the looters which they found in a street on to which the back entrance of the store gave, and then, guided by the big-headed MacBatt, they entered the building quietly.

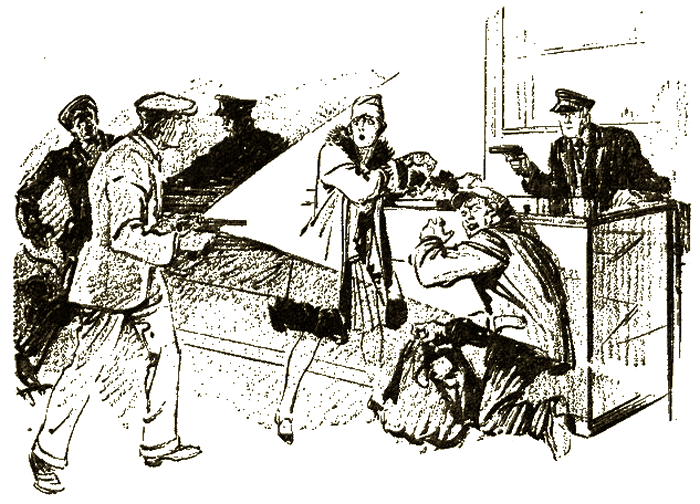

As expected, the Downton trio were in the jewelry department, and the fair Dora was so absorbed in selecting the best articles in stock, and her brace of bravos were so busy packing away what she selected, that they were not aware of the softly moving little cohort of bloodhounds tracking them until they were practically surrounded.

The Downton trio were in the jewelry department, the

fair Dora absorbed in selecting the best articles in stock-

One nearly got away. He dashed wildly for an exit behind one of the counters, but Molossus brought him back a second or so later, loudly demanding that a doctor should be sent for at once to cauterize what Molo had done to his leg. Dora and her fiancé surrendered without argument. They were much too shrewd, it seemed, to import any firearms into the matter. They had revolvers, but very intelligently had left them in their motor—a piece of foresight which had an effect upon the sentences subsequently doled out to them by the judge before whom they were invited to explain matters.

The watchman was found temporarily stunned, but otherwise in good working order, in the leather-goods department—from which the thieves had taken the suit-cases in which they were packing the jewels.

LATE that night, after a little supper in Merlin's suite at the Astoritz, Mr. MacBatt was invited to tell the company present—Merlin, Blackberry Brown, and, of course, the Fitz-Percy—all he knew about the affair.

MacBatt did so readily; he had had plenty of time to prepare his narrative. Whether they believed his story or not, it is difficult to say. But there was a convincing ring about his grim concluding statement:

"I did my best to get Miss Brown's jewels back for her. I thought that girl Downton was in love with me—not knowing she was an expert jewel-thief—and I thought I could persuade her to give them up. I didn't expect her to get her two blackguards to lay in wait for me. If I had, I should have taken a few tools along with me that would have put this lump"—he gingerly touched his brow—"and a few more like it, where they belonged—not on my head!"

Apparently they believed him.

At any rate Blackberry was good for a tenner—deftly passed as she left the suite; Merlin remarked that he would have a chat with him next day—it produced another tenner; and the jaunty, chronically broke old Fitz-Percy bestowed the inestimable privilege of a frank and hearty hand-shake, an approving pat on the shoulder, and a sonorous, "Well done, MacBatt!" upon him; even the sharp-set MacBatt expected no more from that genial old tale-teller.

ON the whole, however, MacBatt was satisfied. The downfall of Dora had cost him a good wedding present, but it had brought him two useful little tenners, and a considerable access of reputation.

"Which I could do very well with," as he subsequently remarked to his friend Henri of the Mediaeval Hall, over a quiet whisky and soda. "But I lost my girl!" he concluded ruefully.

Henri grinned. "That was the best of all the luck—hein?" he said.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.