RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created by Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created by Microsoft Bing

The Saturday Evening Post, 9 August 1919, with "MacKurd"

The Strand Magazine, November 1919, with "MacKurd"

THE man whose card had announced that he was Major John MacKurd. V.C., finished speaking, leaned back in his chair, lit another cigarette, and smilingly awaited the reply of the big banker.

There was nothing in his easy, well-bred attitude to suggest that the proposal he had just made was not quite an ordinary everyday proposal.

But Sir David Glende for a full minute sat speechless, as with surprise, staring very closely at Major MacKurd, who bore the scrutiny of the keen grey eyes with the smiling and invincible tranquillity which appeared never to desert him.

Presently the banker spoke, slowly and very clearly.

"Major MacKurd," he said. "I beg your pardon. I fear I have been guilty of—er—inattention. It is not a customary fault of mine. I think that—quite inadvertently—I must have missed a part of your proposal. Do me the favour to restate it. This time I promise you my whole attention."

Major MacKurd, V.C., nodded cheerily.

"Not at all, sir, not the least little bit in the world, I assure you," he said. "I'll run over it all again with pleasure. I made it a bit brief as I didn't want to bore you. Hate making myself a nuisance."

He carefully readjusted the flesh-coloured patch over his right eye. Then, resuming his cigarette, he fixed his left eye upon the banker.

"It's like this, don't you know—they've rather slung me out of the Army—unfit—one-eyed, wooden foot, and that sort of thing—not to mention the Buzz—and I'm knockin' about loose. Nothing much to do. That quite clear, sir?"

Sir David nodded gravely. He was thinking of his son, reported "Missing, believed killed," and of how oddly this airy stranger reminded him of the boy, but he was able to reassure his visitor that so far he understood the position.

"Of course, there's a bit of pension attached to it—naturally, what?—but I've been rather plotting it out, when the Buzz will let me, and I've about come to the conclusion that it would be a soundish notion to come down into the City."

"Yes?" Sir David nodded, his eyes fast on the three deep vertical wrinkles, only partly concealed by the elastic band of the eye-patch, that seemed permanent on the brow of the V.C. "Quite so. May I ask what is the Buzz?"

"Certainly. It's nothing much, though. It's a soft, thick, cobwebby sort of a buzz in my head. Nothing much—it comes and goes, you know. You know those very soft woolly shawls that one's mother used to wear—that sort of thing—sky-blue. Well, if you wrapped your brain up in one of those and it had a bumble-bee entangled in it buzzing very softly—that's about the idea. Nothing much—but awkward for thinking sometimes, that's all." The banker nodded again.

"I decided to come into the City, and settle down to finance, what?" continued Major MacKurd. "I've got a—a—flair for finance. So I strolled down this morning and noticing this bank the idea came into my head at once. I remembered a pal of mine out there told me once that the banks were frightfully short of bank-clerks, cashiers, and so on—and, as I say, sir, it came to me like a flash to get a position as a cashier, to start with. So I looked in."

He inhaled a mighty lungful of smoke, smiled winningly at the banker, and readjusted his eye-patch again.

"The damned thing's about two sizes too large—keeps slipping, what?" he said, so casually that the profanity was obviously inadvertent and unconscious.

"Cashier, yes. I'm a bit of a dab at arithmetic—bar decimals; never saw much point in decimals, did you, sir?—and, apart from arithmetic, which I suppose doesn't much matter nowadays with these adding machines and all that sort of thing. I like handling bank-notes. Queer, that don't you think, sir? But it's a fact. I love the rustly, silky little beggars—fivers and tenners!"

He hesitated a moment, then, smiling broadly, continued:—

"You've been awfully kind and patient, sir. and I ought to explain, in common honesty, that there's just a chance when the Buzz is on that I might take a few notes home at night to fool about with—making 'em rustle, don't you know—but naturally I shouldn't expect you to be a loser, what? What I mean, of course, is, that I should have to insist on refunding anything you missed or lost through my little peculiarity."

He paused a moment to light another cigarette.

"Salary, of course, I leave to you, sir," he said, politely. "It's experience I'm after, to tell you the truth."

He ceased with an air of having said all that was necessary.

"That's about the scheme I've plotted out," he added; "what do you think of it, sir?"

He waited, surveying with obvious pride the highly-polished brown boot that fitted with such inhumanly immaculate and creaseless perfection over the device of aluminium which he had playfully described as his "wooden foot." He moved it from side to side, smiling.

But Sir David Glende did not smile.

He thought for a long time before he spoke. When at last he replied, the tone of his voice would have surprised those who called him hard—and they were many—and the lines of his grim old face were oddly relaxed.

"Forgive me, Major MacKurd, if I ask you a few personal questions," he said.

"Fire away, sir," replied the smiling V.C.

"How old are you?" '

"Twenty-six."

"What decorations have you?"

"Oh, I've been one of the lucky ones—V.C., you know, M.C., and a French decoration—Croix de Guerre."

"Twenty-six years old," said Sir David, absently.

"Twenty-six, yes. Hope you don't think that's too old to start in the City, sir?"

"Twenty-six, yes. Hope you don't think

that's too old to start in the City, sir?"

"No, no—not at all," said the banker, hurriedly.

He appeared to ponder. Once his hand moved towards his breast-pocket, but stopped.

"You have been in many actions. Major MacKurd? In many places?"

"Heaps of 'em," said the Major, cheerfully. "Rotten things they are, too."

"Did you ever, by any chance, come across a young officer—a lieutenant named Glende—David Glende? He was reported missing after Passchendaele."

Major MacKurd, V.C., reflected, frowning slightly.

"I can't quite recall him—not with the Buzz on," he said. "I fancy I—Glende? Glende?" He smiled apologetically. "One meets such a crowd of men, you know. And the Buzz is rather bad to-day. I'll just make a note of the name and let you know. If I've met him I shall remember it when the Buzz is off. Was he a friend of yours, sir?"

"My only son," said Sir David, very steadily.

Major MacKurd, V.C., said nothing at all to that—only moved one hand very slightly in a quite indescribable gesture, and raided one shoulder the fraction of an inch. But they were the most eloquent movements Sir David Glende had ever seen. They expressed everything—a sense of the pain, the desolation, the waste, the needlessness, the pity, the tragic folly, and the fatalist's acceptance of it all. Only a man who had experienced it all many times could have made those tiny gestures in just that way.

Presently he spoke.

"I wish I could remember him, sir. Perhaps, when the Buzz is off "

"Yes, yes. Take this card—it will keep the name in your mind—if you have no objection."

Sir David passed a visiting-card, which the Major pocketed.

"Now with regard to the position of cashier," said the banker. "I have not complete control of this bank, as you will easily realize. There are partners—fellow-directors—to consult, and an immediate decision is impossible. You understand my position? But I may tell you at once, Major MacKurd, that your proposal impresses me very much and I shall lose no time in going into the matter. Is that satisfactory to you?"

The V.C. smiled.

"Why, naturally. There's no hurry."

"I expect to write to you almost immediately—and I may go so far as to say that I hope to be able in any case to make you a proposal. I shall need your address, of course."

MacKurd, V.C., gave it—a West-end hotel. He was quite "loose," he said—"campin' just anywhere."

"And I should be very glad. Major, if you can find time to lunch with me to-day."

"Pleasure, sir."

"Shall we say one o'clock?"

"Couldn't be better. I'll drop in for you at one, sir. I've got a bit of shopping to do and it will fit in beautifully, what?"

So it was settled.

Sir David accompanied his visitor to the big doors of the bank—and that was an event which the staff discussed throughout the luncheon hour.

"He said he had a proposal to make to the owner of the bank," mused Mr. Wilson, the chief clerk. "It must have been a proposal of the very greatest importance—something unique, I fancy."

And that was true—though it was not the kind of uniqueness which Mr. Wilson meant.

The old Chief Clerk realized that when presently Sir David sent for him.

"You are pretty good at deciphering handwriting, I believe, Wilson." said the banker.

The Chief Clerk, an old ally and henchman of Sir David, smiled a little.

"I should be, Sir David," he admitted.

"Can you read me the line in that letter which is marked with a red cross?" He passed a letter, folded very narrow so that only a few lines were visible.

"Can you read me the line in that letter

which is marked with a red cross?"

"It is Mr. David's writing," said Wilson, and he read aloud:—

"'His name is'—ah! poor Mr. David wrote this in a hurry, sir—h'm!" Mr. Wilson stared at the sentence intently for a moment, then decided.

"'His name is Claskind'—yes, undoubtedly 'Claskind.' An unusual name, sir."

Mr. Wilson handed back the letter.

"Thank you, Wilson. 'Claskind'—yes. I had decided on 'Claskind' myself."

Sir David turned to his writing-table again and the Chief Clerk went out quietly.

Then Sir David unfolded the letter again and read it throughout—and reread it.

Presently he took a pen and a clean sheet of paper, and wrote busily, constantly referring to the letter spread out before him. At the end of a quarter of an hour he had written the words 'Claskind' and 'MacKurd' dozens of times in as many different handwritings as he could accomplish. He surveyed his work for a few seconds, then shook his head ruefully.

"Ah, Davie, boy," he said, "is it 'Claskind'? or have you made 'Claskind' out of 'MacKurd'? It seems impossible, but out there—as you say——" He turned to the end of the letter and read aloud:—

"Forgive the scrawl, father, but I'm writing with shells joggling my elbow, so to speak—Jerry's evening strafe—and time's short."

The banker muttered the last words softly.

"'Time's short.'"

The old man stiffened abruptly, compressed his lips, put all away, and stared blankly before him, thinking.

At last he rose.

"It's impossible to make him a cashier—although he's 'rather a dab at arithmetic,'" A faint smile twitched his lips. "We can't have unknown quantities of notes sleeping out of the bank at any odd moment the fit takes him. It's impossible. And yet I have an instinct that he's the man who saved Davie from that terrible thing. I shall do something for him—whether my instinct is right or wrong. That, at least."

His lips twitched again, as he thought of Major MacKurd's airy proposal,

But as he took his hat his face grew very serious, for his mind harked back yet once more to Davie's letter—to the few phrases that were burnt in on the father's mind.

### LETTER

"He saved me from myself, father I was in a blue funk—in another minute my nerve would have gone and I should have bolted. My God, think of it, father I—bolted—in front of my own men. He came like an angel from heaven—I mean that absolutely—as cool, as steady, as self-possessed as steel. How I envied him. He spotted my trouble in a flash. 'It's pretty hard when it gets a claw into you, eh?' he said. 'I was that way at Ypres. Most fellows are—once—you know.' We talked for a few minutes and presently I went right—with a click—as swiftly as a camera shutter. The relief of it! I was no longer afraid, father I could have kissed his boots. He saw it and he laughed a little and nodded. 'It's gone?' he said. 'Quite,' I said. 'I shall never be able to repay you.' But he laughed and shook hands. 'My dear chap it's nothing! I had my dose at Ypres. I'll be moving.' And soon after we went 'over' and I was as right as rain. His name was Claskind—and I owe him far more than my life—far more. father—"

Yes, it was burnt in on Sir David's mind, all that letter. And somewhere deep down in his heart there was established a wonderful instinct—developing momentarily to a conviction—that the hastily-scrawled "Claskind" stood for "MacKurd."

The clock struck one while Sir David pondered the thing, slowly pacing his room—one and two and three o'clock, but Major MacKurd, V.C., did not return.

"It is the Buzz—he's forgotten the appointment," said the banker, rigorously controlling himself. It was the bitterest disappointment he had ever known.

"I was wrong to let him go—in that state. The folly of it!"

He touched a bell and ordered his car.

But MacKurd, V.C., was not at his hotel, and nobody there appeared to know when he would return.

Sir David went back to his bank and wrote a letter.The clock struck four as he signed it.

Then he went to lunch—what time MacKurd, V.C., drifted to quiet harbourage in an ornate West-end chemin-de-fer den, started on his second bottle of champagne, and broke into the third hundred pounds of his financial reserve. The Buzz was rather bad that day, and he had an idea that a little champagne and a little relaxation were good for it.

The other matter, his City enterprise, had quite slipped his mind.

II.

But at eleven o'clock the next morning MacKurd, V.C., opened and read the following letter from Sir David Gilde:—

### LETTER

"I have thought a great deal about your proposal, and I am very glad to be able to say that I have a plan to propose which, I think, will render it unnecessary for you to go through the drudgery of a cashier's work at this bank in order to acquire financial experience. For some time past I have found myself increasingly in need of another private secretary at my home, and I am very glad indeed to be able to invite your acceptance of the position. The actual work will not be excessive, but it will, as my arrangements for the future develop, become more and more important and confidential. The salary I suggest is one thousand pounds a year,and I must stipulate that you live at my house. I can promise, I think, that you will have, in this position, opportunities of acquiring an experience of finance which might not be easily available to you in any other position.

"I trust, my dear Major MacKurd, to have the pleasure of receiving your acceptance verbally from you, and hope that you will find it convenient to call and see me at the bank to-day.^

"Yours very sincerely,

"David Ross Glende."

MacKurd put the letter down and surveyed the smoke of his cigarette as it curled ceilingwards.

The Buzz was rather pronounced this morning—also his brain seemed queer—shaky—quivering steadily, like heat-waves.

But he realized that this was an extremely kind letter.

"He's a decent old boy and I'll give it a bit of a trial, what?" said MacKurd. "I'm not so keen on it as I fancied—but. hang it all! it's a chance to learn how to run banks, form fours—no, companies—ha! ha! Promote 'em, what? Promoted plenty of men in my time—promote companies now. Not too bad, what? First shot! Hang this Buzz!"

He touched his bell and ordered a bottle of champagne.

It occurred to him to look at his bank-book before he left the hotel. A little figuring showed him that he had precisely five pounds left with which to carry on. The cheque he had written overnight at the chemin-de-fer den had reduced him to that.

When, presently, he stepped into the taxi which was to take him down to the City the Buzz was no more than a faint, far, tiny drone. He had seen to that. He was a little pale, but one watching him would never have dreamed that MacKurd, V.C., was a nervous wreck, flying at a fearful speed upon a swift, golden stream of champagne to the rapids of insanity and the deep falls of death.

It never occurred to him that the offer of the old banker was anything unusual—that, viewed as a purely business transaction, Sir David had been liberal to the point of absurdity. Had some truth-teller, with a heart of marble, arisen and told MacKurd, V.C., that his value in the market as a secretary to a financial magnate was not a thousand a year and a luxurious home, but literally nil, the V.C. would have laughed, jokingly called the truth-teller a pessimist, and suggested a small bottle.

Sir David Glende was on the point of going to lunch when MacKurd, V.C., reached the bank.

The banker's face lighted up a little as he saw that, this time, the Major had kept the appointment.

They shook hands, and without embarrassment MacKurd asked the banker to pay the taxi-driver.

"So you have decided to accept my proposal? I am very glad—very glad," said Sir David. "You won't mind living mainly in the country?"

MacKurd smiled rather vaguely, for the Buzz was bothering him.

"Certainly not—as long as there's plenty of champagne, what?" he said.

"You are fond of champagne?" asked Sir David, steadily.

"Not especially—for myself, you understand. But it keeps the Buzz quiet. Somebody suggested morphia last night, but I don't fancy that morphia's got quite the kick of champagne, do you, sir?"

The banker appeared to ponder.

"No, I should say not. I think you will do better to stick to champagne. I think there may be a medical friend of mine lunching with us." (He had arranged that.) " Suppose we put the question to him?"

"Sound scheme, sir—very, what?" said the V.C. secretary.

III.

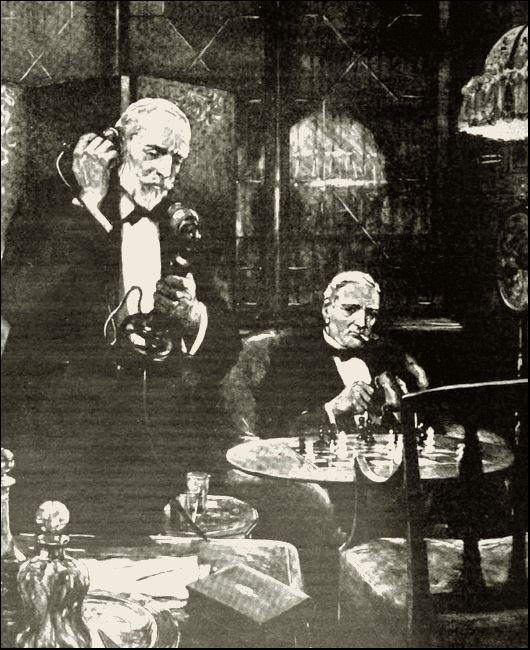

ON an evening about six weeks later Sir David Glende was sitting in his library with an old friend—the local practitioner in the village whereof the banker was the modern equivalent of the old-time squire—largely the owner, that is. Dr. Owen Fansley and Sir David had played a round of golf that afternoon, dined together, and had come to the big, cool library for a chat and a game of chess.

They had been there some hours already, sitting by the open window, staring out at the grey velvet twilight of the midsummer evening, but their conversation was still earnest, and the set of chessmen stood neglected on the table close by.

"The matter is worrying me more and more, Fansley," said the old banker. "It is all going wrong—wrong. I know it, I see it—anyone could see it. The man is headed straight for insanity and death. There are ugly words for some of the things he has done—and few men would hesitate to use them. I suppose I am soft—weak. That is not my reputation, either—but I suppose the hardest man has somewhere in him a soft spot—a weak link."

He paused, musing, staring out across the shadowy park.

Then he spoke abruptly.

"You have had to do with a side of human nature which is not very familiar to me, Fansley," he said. "Advise me. What am I to do about MacKurd?"

The old doctor moved his head in a gesture which deprecated urgency.

"You must tell me more of the peculiarities and eccentricities of which you complain before I can suggest anything, David," he said.

Sir David nodded.

"Yes, of course. Well, you know him—and you know that he is not normal."

"Far from it," said the doctor, gravely.

"And it is possible that he is seriously—deranged?" There was a question in the banker's tone.

"Well—let us leave that open for a little. Go on."

Sir David hesitated a moment, then spoke abruptly.

"The fact is I'm afraid he is devoid of common honesty!"

"Ah! But I thought he warned you of that?" Sir David shook his head.

"No. He told me that he might take banknotes—not as money but as—er—toys! Because they fascinated him. He was very precise and insistent about returning them. He meant it, too. I am quite sure of that. He meant it—then, at any rate. He appeared to regard it as amusing—in the way a truly humorous thing is amusing, not as that which is cynical or sardonic may be amusing. I am quite convinced of that. Let us leave that for a moment. He drinks enormously—champagne—though during the last week he has been drinking brandy with it. He adds champagne to a stiff brandy as one adds water to whisky. But he is never drunk—he never gives the minutest sign that he has touched alcohol. That is—frightening, Fansley. And he gambles with the wild magnificence of one insane. I have accompanied him twice to evil, discreet dens in the West-end, and I have had almost to pinch myself to be sure that I was not dreaming. He is incredibly unreliable. You know, my idea was to give him a sinecure—to ride about the place, amusing himself with the supervision of the shooting, the rearing of the game, such as the war has left us with, the trout, the farm, reconstructing the golf course—and landscape gardening—anything, a free hand, and, practically, carte blanche. Was that difficult?" There was an odd, unexpected quaver in the banker's voice. "Was there anything in that which any sane man with the instincts of a gentleman such as MacKurd obviously has been could find onerous or irksome? Yet this wild-man has failed to keep within even such bounds. Bounds, do I say? Why, there were no bounds—in all human reason. I have made him free of all I have—except only that I cannot bring myself to let him meet Madeline. That is the real reason why she has been in Scotland for the last six weeks."

Sir David paused, breathless, for a second. Then, dropping his voice, he said: "Owen, listen to this ! MacKurd has thrown away eleven thousand pounds of my money in the last six weeks—and I find to-night that he has—"

He stopped short as the door opened and MacKurd, V.C., looked in.

"Are you engaged, Sir David? Shall I switch on the light?" he asked, in his pleasant voice.

"No, no—switch on, do."

The bunches of electric bulbs on the carved ceiling and panelled walls glowed softly, revealing MacKurd in evening dress under a magnificent fur coat, at the door.

"I am sorry to interrupt, but if you are not using the big car to-night, sir, I had rather plotted out a little run up to town."

There was a brief silence. Then the banker cleared his throat.

"Very well, my boy," he said.

"Thanks very much, sir."

MacKurd half turned, then stopped.

"Oh, by the way, I'd quite forgotten. I owe you five hundred of the best, sir. I ran out in town yesterday; you were down here and it was rather awkward. So I wrote a cheque, signed it for you and cashed it at the bank. Rather sound scheme, what?" He laughed pleasantly, said "Good-night," and went.

Sir David looked at the doctor, his lips trembling and his eyes full of misery.

Fansley had flushed slightly, half rising from his chair.

"Oh, but this is absurd—" he began.

restrained himself, and sat again.

"You see? That is what I was going to tell you! And how can one call it forgery? He must be mad!" said the banker.

"Mad? No. I have examined him—how many times? I will stake my reputation that he is sane!" exclaimed the medical man.

He waited, but Sir David said no more.

"Why do you permit it? Has he a hold on you?" asked Fansley.

"Yes."

"It is a strangle-hold! Are you being blackmailed?"

"God forbid! No—I give. Freely I give. It's not the actual money I mind, God knows "

"Why do you give?"

Sir David took from his pocket the letter in which his dead son spoke of "Claskind."

"Perhaps I am wrong—an old fool," he said, humbly. "But this is one of the reasons I want to befriend MacKurd."

He told the doctor the story of Davie, read him the letter, and explained his singular fancy that Claskind and MacKurd were the same man.

Long before he had finished the doctor's face had cleared, and when the old banker had said his last word and was returning Davie's letter to his pocket, he leaned forward, speaking briskly, with the air of one who would finish the matter forthright.

"He, MacKurd, does not remember Davie—or any occasion upon which he encouraged or steadied him?"

"No. He says so frankly. I have often asked him. But his memory is appalling!"

Nevertheless it is highly improbable that he was the man who befriended poor Davie. Why—what real grounds are there for believing he was? He is of a different regiment—"

"But both were in action at Davie's first battle!"

"True—and many others, David. Let me go on. The fault is with you—no, not in any personal sense—I mean, your health—Listen. You came very near a breakdown during the war—nearer than you suspect. Only I—whose duty it is to know—know how near. This man—this feather-headed adventurer—came upon you in a moment of reaction—and the idea that he was the man Davie meant lodged itself in your mind—like a seed in a crevice upon a cliff-face. You did not dislodge it—on the other hand you welcomed it. One easily understands that you would welcome it. It is natural that you should. Also there is no doubt that MacKurd, in spite of his fatuous irresponsibility, is a man of singular personal charm. A nice boy prematurely aged, who has suffered horribly for a long time. So the seed rooted—and so it is just that much more difficult to dislodge. Confess it, David—you look upon MacKurd very much as one might look upon a son of whom one could be proud were he not so—wild?"

The grey head of the old banker drooped.

"Yes. that is so."

Fansley nodded slightly, and continued:—

"But, you see, David, that you are doing him no good—indeed, you are giving him the means to do himself harm. He will throw away all you give him—all you allow him to take—to his own detriment. He needs discipline, not indulgence."

He pondered a little.

"You can't send a man to hospital because he drinks too much champagne to lull a buzzing in the head, which a period of peacefulness in country-side silences, fresh air, wholesome food, exercise, and lots of sleep, will cure. You can't put a man in a nursing-home because he gambles and signs another man's name to cheques to pay his losses. You can only discipline him."

"You may as well speak of disciplining a butterfly, my dear Owen," said the banker. "He is utterly irresponsible."

"Why?" asked Fansley. "You don't know. I will tell you. He is as he is because he is aimless—without an objective. He needs nothing. He is striving for nothing. Sex, you say, means nothing to him, and he is not susceptible to feminine charm or influence—but, wisely, you do not wish your daughter to meet him. Money he has in plenty—thanks to you—and everything else."

The doctor leaned forward, putting his hand on the other's arm.

"David, old friend, you must harden your heart if you are going to prove a real friend to this man," he said.

"But—what am I to do? I still believe he is the man Davie wrote of. Am I to turn him out—penniless, save for his pension? Why, he would be in prison before a month was up."

"Better a prison ward from which there is an exit than that cul-de-sac the grave," said the doctor.

The banker drew a sharp breath.

"My God!—a man who has fought so—for us, who sat snugly at home and took the profits that were literally thrown at us! A man who had been torn apart with hot metal—as he has—as so many have! Aren't there any proper places for such cases, in the England they paid flesh and blood and sanity and souls to guard?"

"His health is excellent," said the doctor, inexorably truthful. "His Buzz would die out in a month of sane living. He—"

A muffled telephone-bell rippled gently on the big writing-desk. Sir David answered abstractedly, but that was only for a second. A sudden flush burnt on his thin face; and he spoke sharply.

The doctor watched him, not without affection. They were old cronies, these two. Perhaps it was that which rendered the medical man harsher in his judgment of MacKurd than he might have been had Sir David been an ordinary client.

The Sir David of private life had disappeared now, though—it was Glende, the money-captain, that shrewd, keen, skilled navigator on the treacherous sea of finance, who was speaking at the telephone now—clearly, incisively.

"I am grateful that you have notified me without delay. Yes, bring him as quickly as possible. Ignore expense, please. Are there preparations of any nature for his reception which you require to be made here? I have a medical man—a personal friend—here with me now, and he will remain."

"Yes, bring him as quickly as possible. I have a medical man—

a personal friend—here with me now, and he will remain."

He was speaking with an iron control over his voice—but Fansley saw that the hand gripping the receiver was shaking.

"Very good. I shall be ready for you. Thank you. Good-bye."

He replaced the receiver and turned to his friend. He was stone pale now. He sat down, resting his elbows on his knees and his head on his hands.

"Oh. God!—please—please—" he muttered, brokenly.

Fansley sat silent, watching him but leaving him alone.

Through the warm velvet darkness outside there swam the low thrumming of a high-powered motor, like the deep soft boom of a bee. A great aura of white light from that car's lamps was swinging through the night towards the house. A thought struck the doctor, and he went quietly to the open casement, listening. It seemed to him that the note of the car was familiar to him.

"That's Madeline's car—surely," he half-whispered! The sound died down and the white blaze dropped. The car was running down the dip before breasting the steep hill that led to the entrance-gates.

Fansley listened.

Deep in the heart of the drowsy gloom far back in the wood a nightingale was singing, and its notes lay upon the beauty of the night like pearls upon a black and glossy cloak. Accustomed though he was to the country-side night, yet this night, he felt, was pregnant with the promise of events. It was as though somewhere out in the great warm darkness the Fates were stirring—Life, with her wide, vivid eyes, her laughing lips, bedecked with flowers; Love, with her flushed face, her swimming gaze, her white hands; and, perhaps, Death, too, sombre, wreathed with nightshade, darkling and sorrowful, moved mysteriously hesitant, gazing towards the house.

Then the fierce shout of an electric horn shattered the spell, and Fansley turned back to his friend.

The old banker had recovered himself now. He stared at the doctor.

"Owen," he said, "they have telephoned to say that they are bringing a man here to-night—at once—who is a returned prisoner of war. He is young and unwounded—but he has lost his memory utterly. He has never spoken of his life previous to his capture by the Germans, dazed, shell-shocked, in the rags of what was once an officer's uniform, at Passchendaele. To-day, for the first time, he mentioned a name—apropos of nothing, it seems. He uttered my name three times. Nothing more, but the nurse reported it. The doctor—a man I know slightly—happened to know that my son was reported 'Missing—believed killed' at Passchendaele—and he has suggested bringing him to see me at the earliest moment. And they are now on the way! And it may be Davie!"

Without speaking, Fansley caught both his friend's hands in his and wrung them hard.

"Thank you, old friend," said Sir David. He stared out into the night, his lips moving.

The whirring boom of the approaching car waxed louder as the machine came up over the hill. Fansley watched the white glare and saw that the car had turned in at the lodge gates. It was coming to the house.

"Yes, it's Madeline," he said to himself. "This is ordained." For he knew that Sir David had not expected his daughter home from Scotland for a month yet. But he was not surprised. It seemed to him that this night was not to be as other nights. The workings of Fate were more visible, he thought—the spinning of one infinitesimal fragment of the great universal fabric was plainer to be seen—though how it would finish it was impossible to say. There was to be a climax there, that night, he was sure of that—the threads were coming to take their place in the design, the tiny specks were drawing near to their exact positions in the mosaic.

He nodded absently, wondering, with a nervous curiosity, whether the dénouement for which Fate was so plainly preparing was to be tragic or otherwise. He looked at his friend, the great financier, praying in his chair; he pictured that silent, broken, nerve-shattered man without a memory whom they were bringing even now; he considered, not without pity, MacKurd, V.C.—odd that he only should be absent; and lastly, he thought of Madeline. How fitting that she should come home, without warning though it was, this night.

The door opened and the girl came in quickly.

She still wore her thin summer motor wraps. They were white with the dust of a long journey. And her beautiful face was pale with fatigue and her dark eyes looked jet black within the shadows which weariness had painted round them.

Sir David looked up, staring.

"Why, Madeline—my dear little girl! Where have you sprung from? Never from Scotland to-day!"

She was pushing him back in his chair, caressing him.

"Yes, daddy dear, yes, yes, yes! With only one stop for lunch and one for petrol!"

"But why, my dear, why? Is anything wrong at Stanes?" He spoke of his Scotch estate where Madeline had been staying—partly, on Fansley's advice, to recuperate, after a spring chill, and partly as company for Sir David's sister, a semi-invalid, passionately fond of Scotland.

"All's well there and the place is lovely—but I had an impulse yesterday, daddy. Like a great wave—overwhelming. Something sent me here—if an actual living person had stood before me and said, 'Hurry home to your father, he is in need of you!' it could not have been clearer. I did not attempt to resist it. We started at the very peep o' dawn this morning—and oh, daddy, the new Sunbeam is such a good, honest little car. Thank you so much for her—she reeled off all those long miles like a dream, and Griffiths is such a splendid chauffeur: we drove in spells—and so—and so—here I am, and are you all right, dear? Is he all right, doctor?"

"Perfectly, Madeline, my dear child," said Fansley, with the privilege of an old, old friend—and one, moreover, who had attended her arrival into the world.

She settled on the arm of her father's chair, one hand on his shoulder.

"So my impulse meant just—nothing?"

Fansley smiled gravely.

"Oh, I shouldn't say that—yet," he answered. And they all turned abruptly as the door was opened rather violently.

Major MacKurd, V.C., had returned.

He stood upon the threshold, surveying them—deadly pale, his head heavily swathed in bandages, one hand bandaged and one lapel of his big fur collar half torn off. There was dried blood on the white front of his dress shirt, and a smear of blood on his face.

"Oh, I beg pardon," he said, dully. "I hadn't the remotest idea that you were engaged, sir—not the remotest, what?"

He would have gone with that, but Sir David stopped him.

"Why, what's happened, my boy? Don't go. Here's work for you, Fansley. Come in, Major. This is Madeline, my daughter—of whom I have spoken to you."

(But he had not spoken much of her, nor very often.)

Slowly MacKurd limped forward. He bowed, rather painfully, but his eyes clung to Madeline.

"I hope I don't look too much of a blessé," he said, painfully. "But we have had rather a spill. The Lanchester got badly ditched a few miles out—and I went through the screen, what? Grayson is all right—not a scratch. I was driving."

He was addressing them all—but he never moved his eyes from Madeline. She, too, was looking at him as she did not usually look at a stranger. As Fansley stepped forward to give a professional glance at the bandages a phrase detached itself from the conversation of that evening, driving through his mind—

"He is not susceptible to feminine charm!" But—he was looking at Madeline with a rapt scrutiny that was odd in one who was so impervious to feminine attraction.

"Who bandaged you, MacKurd?" he asked.

Even as he spoke a motor-born brayed sharply down the drive—and Sir David turned quickly to the French window.

"Here they are, Fansley!" he said, and his voice cracked as, bareheaded, he disappeared into the darkness. But the stabbing glare of the lamps on the big ambulance car that came gliding up dazzled him and he stepped back with a stifled exclamation of impatience.

A little crowd appeared round the hospital car like magic, even as Fansley, using all his self-control against an impulse of fierce excitement that boiled up in his veins, slipped his arm through that of Sir David.

"Steady does it! Mind, now—steady, David, say—"

Steady! But even his professional heart was racing.

The butler and footmen who had been on the qui vive for the past hour fell back, making way for the two men who came forward towards the open window.

"This way," said Fansley, and stepped aside as they moved into the lighted room—two men in khaki, one an elderly, worn man, an R.A.M.C. Major, the other little more than a boy, but with blank eyes and an old man's face. It was Davie!

He came forward, the hand of the doctor on his shoulder.

"Let me introduce you to Sir David Glende— Sir—David—Glende, your father, old man!" said the military doctor, very slowly and distinctly.

Politely, but without a gleam of recognition, the prematurely-aged boy saluted.

"How are you, sir?" he said.

Sudden tears rolled down the face of the City banker, as he reached for the boy's hands.

"Ah, Davie, my boy—my boy!" he muttered, his lips quivering.

"Just one moment, sir," broke in the military doctor, who had been whispering to Fansley, and turned the boy to his sister.

"Glende!" he said, with a certain sharpness in his voice. "This is Madeline—your sister!"

The boy bowed, looking puzzled.

The doctor tried again.

"Here is Dr. Fansley—an old friend of yours!" he said.

Again the polite, blank stare.

"Don't you remember us, Davie—Madeline and your dad?" begged the banker. "Davie—try! For God's sake, try! And Fansley—who taught you golf."

Then it was that MacKurd, V.C., saw fit to lurch forward—a ghastly figure, bandaged, pale as death, a smear of blood down his dust-streaked face, his eyes glittering.

He laughed—a short, harsh cackle, and brought his uninjured hand down heavily on the shoulder of the memoryless boy, staring hard at him with gleaming, bloodshot eyes.

"Well, old son, so you got through, hey, what?" he bawled, in a voice quite unlike that which he normally used. "Some show, what? But the blighter's for it this time. He's on the run! How's your nerve now, son? And have you got a drink on you of any sort?"

MacKurd laughed—a short, harsh cackle, and brought his uninjured hand

down heavily on the shoulder of the memoryless boy, staring hard at him

with gleaming, bloodshot eyes. "Well, old son, so you got through, hey, what?"

For a second they all fell back from him in a consternation that was akin to terror, for he looked like one mad—all save Davie.

He did not fall back. Instead, he punched, with a species of fey playfulness, at MacKurd's chest. And there was a sudden light in his eyes as he shouted back:—

"You! You, is it, MacKurd? Oh, good luck! Drink? No—I'm as dry as tinder!"

For a moment they shouted strange, profane congratulations at each other—lamenting the lack of a drink. They looked horribly ill. That their tortured brains had tricked them into believing that they were meeting again after some "do," which was perhaps Davie's first battle, was self-evident. MacKurd was swaying on the edge of collapse.

Then the R.A.M.C. Major was inspired. He seized the decanter on a small stand near the chess table, poured two dazing doses of whisky, and pressed forward.

"Who said 'drinks'? Here you are, boys," he barked, and crammed the glasses into their hands.

They drank thirstily, and fumbled for cigarettes, talking swiftly as they fumbled.

With his eyes and a most expressive gesture the military doctor drew Sir David, Madeline, and Fansley with him out through the French window.

"Give them a little while!" he said. "It may be only a few minutes! What an amazing stroke of luck that that wild-looking chap was there? Who is he?"

"That is Major MacKurd, V C.," said the banker, quickly, defensively. "He befriended Davie when he first went under fire—and Davie worships him."

"MacKurd, eh?" said the Major. "What's he doing here?—he should be in hospital."

"Ah, Major—his wounds are very recent—" Fansley came forward—"take a turn with me."

He slipped his arm through that of the R.A.M.C. Major and they paced up and down the lawn briskly, talking.

On the terrace just outside the French window Sir David and Madeline waited, holding hands like children—listening with a strained and painful intensity to the high-pitched voices inside the library.

"He will remember, dear—he will remember, dear—he will remember, dear—"

Madeline was saying it over and over again.

The voices were sinking to a more tranquil, everyday note. The listeners could no longer distinguish what was said. Their hand-grip tightened—and then, suddenly, they heard Davie's voice speaking naturally, with a ring of wild surprise.

"But—I say, you know, MacKurd, I know this billet! Why, I'm hanged if it isn't my home! My home! This is the library—at Netherby—my governor's room! Why—"

The R.A.M.C. officer hurried up. He, too, had heard that cry of amazement.

"Quick! Quick! In you go!" he said, and literally pushed Madeline and Sir David into the room.

"It's now or never!" he snapped to Fansley.

And it was now.

"Father! Madeline!"

The cry cleaved through the room like the sabre-note of a strongly-bowed violin string. Never before had the boy uttered the words in quite that way before, never would he again. There was a strange, deep joy in it, amazement as swift as light, as poignant as pain, with gratitude, relief, triumph. It was the cry of a slave who wakes to freedom from a sleep begun in bondage.

He went to his people with open arms and shining eyes.

"Then I am home—truly home again?" he said.

"Ah, yes—home again, David!"

The banker gripped his son's hands—so that it was Madeline who hurried with a cry of pity to MacKurd, V.C., who had fallen back on the big lounge, with a long, curious sigh.

Fansley went quickly to him. The R.A.M.C. Major was watching Davie with a little smile of satisfaction on his lips.

"Is he—?" asked Madeline, hesitating.

"Oh, no—it's just a faint. He's not fit yet—but he will be all right," said the doctor.

Madeline leaned close to whisper.

"Make him well, doctor, oh, be sure to make him well!" she breathed. "He has done so much for us all—did you hear father say he befriended Davie?. And now he has restored his memory!"

"I will, my dear," said Fansley, with singular confidence. "And I think—I think—you will find that Davie has restored something to MacKurd!"

And, before the week was past, they knew that it was indeed so. The culminating excitement of Davie's arrival, following the shock of the motor accident, had straightened out that odd little twist in the mind of the V.C. which inspired the erratic wildness characterizing him before that evening.

They did not learn that at once—but when, many months later, Sir David Glende gave his daughter into the care of MacKurd, it was without any doubt or fear of the future that he did so. For, even as Davie had come back to his own home and his own memory again, so MacKurd, V.C., had come back to his own manhood. And the Buzz was utterly gone.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.