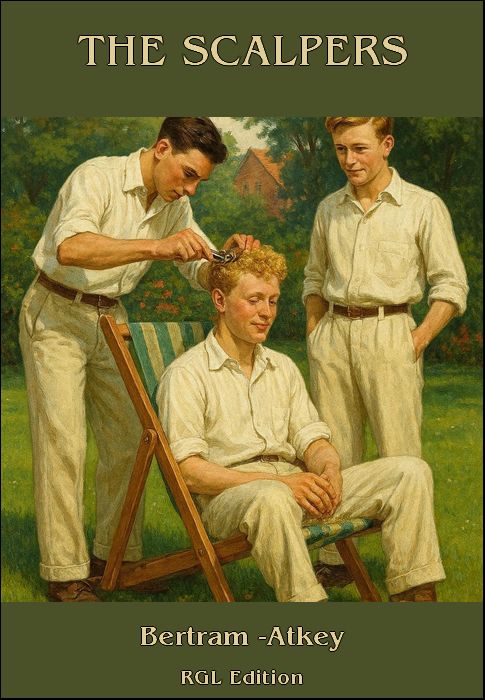

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created by Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created by Microsoft Bing

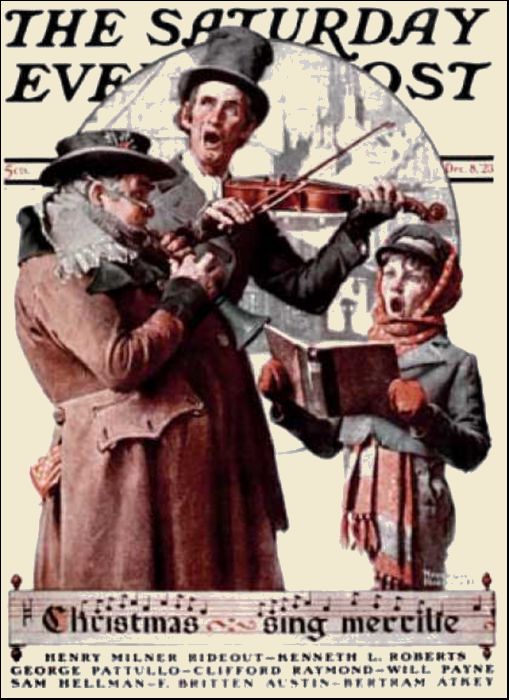

The Saturday Evening Post, 8 December, 1923, with "The Scalpers"

THE Tressidder brothers stood side by side, staring gloomily out of the window at a couple on the tennis lawn at the front of the house. "When I think that a sister of ours—a pretty kid, in her way, too—has let herself be vamped by a thing like that, it puts me off my drive absolutely!" said Tom Tressidder, local golf champion.

"If only the useless bounder would cut his greasy locks it would help a little—not much—but still it would help. And it might put young Dulcie completely off him and his poetry too!" chimed Tim Tressidder, the local tennis crack.

They continued to stare at the trim and dainty girl, their sister, who sat in a deck-chair raptly listening to the utterances to which the young gentleman whom the brothers were discussing was giving impassioned vent.

"She was coming on with her iron shots quite decently," said Tom, "until the cat found that thing in the woods and brought it into the home."

"And if it comes to that, she was working her way well on to making a bit of a noise at tennis," claimed Tim," until that velvet-coated short circuit distracted her attention."

Tom Tressidder scowled.

"Grr-rr! I say, Tim, d'ye think she's really in—er—in love with him?"

The younger brother flushed angrily.

"Oh, damn it, that's impossible! She's usually such a sane kid. Look at the way she runs this house. Clockwork, what I mean to say. She can't love a velvet-coated fuzzy-wuzzy freak like that. I think it's more of a morbid fascination."

"But what the dickens is it that fascinates her? It can't be his face. Chap's only got an ordinary face. Neither-one-thing-nor-the-other sort of face. His politeness?"

"Fellow's no more polite than any other decent man. Hundreds of men about the place as polite as frizzy out there."

"Well, is it this poetry he keeps grinding out?"

"I dunno—I don't understand the stuff any more than you do—or Dulcie—or the blighter himself. He writes it, but he don't understand it. I heard him reading a blinking sonnet or lyric or hysteric or something to Dulcie yesterday, and I simply couldn't stick it. I broke in on him. I asked him to explain to me what he meant by a line he'd just read. It went something like this: 'The dreaming flowers stand with listless heads and folded hands.'

"'Now, what d'ye mean by that?' I said. 'What are you trying to convey to people? What kind of flowers are they? Hands? What hands? Flowers haven't got hands. How d'ye mean "listless," too?'

"'Lilies—tall, pale lilies—the golden-rayed lilies of old Japan,' brayed the ass, and went on reading.

"Lilies—tall, pale lilies—the golden-rayed lilies of

old Japan," brayed the ass, and went on reading.

"Presently he came to this—something like it: 'The brazen color scream of untamed tiger blooms.' Dulcie was following him like a girl in a dream. Fancy a girl who can play a forehand drive like hers listening to that sort of muck! I barged in again, absolutely sick, old man.

"'Half a minute,' I said. 'What are you talking about?' I said. 'What d'ye mean by tiger blooms?'

"'Lilies—tiger lilies/

"'Well, why don't you call a lily a lily? And they aren't untamed—they're tame. It's all wrong. Bags of 'em round in the greenhouse as tame as—as—the tomatoes. And they aren't brazen—they're ordinary spotted flowers—tame ones. And their color scheme isn't any—'

"The bloke sighed, Tom, and looked weary.

"'Color scream, not color scheme,' he said. 'I am conveying the jarring, brassy trumpet-like sound which the fierce colors of those blooms echo and re-echo around them.'

"'Echo—an' re-echo!' I echoed a bit feebly, old chap, I'll admit. Dulcie laughed in that rotten, pitying sort of way she's learned since she met the long-haired hound, and I pushed off. Couldn't stick it."

Brother Tom Tressidder nodded.

"I know—I know," he agreed sympathetically. "Bill Laffan says she's not fascinated so much by his infernal poetry as by his curly locks. As a doctor, he ought to know. I was talking to him down at the clubhouse yesterday, and he said it was a scientific fact that no woman is proof against this golden curly hair worn longish. Sounds mad, don't it? Old Bill thinks no end of Dulcie; fact, he's in love with her himself, but he was saying that his style of looks is too rugged to beat this poetic bloke's."

Tim agreed.

"Yea. Bill's as sound—as sound as steel; but he's a bit rough-hewn."

"Anyway, he says that, speaking as a doctor, nothing but the loss of Haremain's hair will cure Dulcie of her infatuation. "

"Loss of—"

The brothers stared, struck by the same idea simultaneously.

"Well, but if that's all, can't we manage a little thing like that?" said Thomas. "I'd do worse than that to save young Dulcie from that bounder. I tell you what—let's drift down to the clubhouse and have a chat with Bill Laffan about it. If that's true—why, what are we worrying about? Give me a pair of clippers and Haremain's head between my knees, and I'd glory in the bally act!"

The brothers, slightly cheered, sallied forth without delay.

IT WAS in the joint opinion of the Tressidder brothers a very grievous affliction that their pretty sister Dulcie should have fallen in love with a long-haired poet, and since she was the only sister they possessed it is not greatly to be wondered at that their chagrin was great, their objections fierce and their denunciations extravagant.

They were just beginning to feel that Dulcie would yet be a credit to the family—provided she practiced her forehand drive diligently and ceased not to study untiringly her iron shots—when the poet first crawled over their horizon and completely spoiled their entire outlook on life.

At first they had not viewed the matter with any real concern, for they believed Dulcie to be a girl with some notion of the fitness of things. She had long ago proved to them that in the ordinary affairs of ordinary life she was as practical as she was pretty, for ever since the death of their parents, some two years before, she had run the house perfectly and so economically that the income which each of the three had inherited proved to be considerably in excess of what—being people of simple tastes and single minded ambitions—they needed. Tim Tressidder lived only for the day when he would burst into the tennis championship class like a thunderbolt from the void; and Tom dreamed ever about, and labored incessantly to gain, just that extra bit of finish and skill which would put him high up on the rickety ladder of the amateur golf championship. Work never happened to occur to them.

Both had looked for great things on the tennis court and golf course from Dulcie—and now she seemed to have committed a species of hara-kiri by falling in love with a creature which wore its hair long and bushy, and sometimes kept itself warm with a velvet coat, and devised deliriums about brassy color screams and flowers with folded hands.

What really made it so much more nauseating was the fact that this poetic person, Hamelyn Haremain, might in happier circumstances have escaped being what he was and have done decently well for himself in other fields.

The fellow seemed to have some money—the brothers had gathered that he was master of perhaps seven or eight hundred a year and though by no means built on such s heftsome scale as the Tressidder brothers, he was neither precisely deformed nor half-witted. He was slightly over the average height and he was symmetrically built. Indeed, Dulcie had once claimed that he was quite strong and that he had proved it by the solution of some weight-lifting problem or other connected with her little twin-cylinder, air-cooled runabout—on the occasion when quite inadvertently she had driven into a pond down Dorking way.

But this claim the brothers had derided with brotherly frankness. No man who was afflicted with ingrowing poetry and who wore his hair long and fuzzy could be strong, they maintained with scornful heat and inflexible decision.

Dulcie had quoted Samson.

"He was long-haired and he slew Philistines."

"Yea—with the jawbone of an ass; just as Haremain half-slays me every time he opens his mouth!" shouted Brother Thomas, ably supported by Brother Timothy, who quietly but firmly pointed out to the misguided little lady that Samson belonged to ancient history when possibly, he conceded tactfully, long-haired men were strong. But he maintained resolutely that the strong men of today were universally short-haired as, for example, gentle Jack Dempsey or mild Mr. Beckett.

Outvoted, outargued and outshouted on this matter of hair length and physical excellence, Miss Tressidder had abandoned that ground and had taken up a position fortified, as one might say, by the brains of Mr. Haremain.

"You may sneer at him because he's gentle and spends his time thinking of more important things than golf and tennis, but it would be better for you both if you had half the talent and genius and brains that Hamelyn possesses."

"Brains!" echoed the brothers, aghast. "But, Dulcie, he hasn't got any brains. He wears a velvet coat."

"Not always," defended Dulcie. "And you think he hasn't any brains simply because he has to talk to you in short, simple words that you can understand. He explained that to me the other day. And he paid you compliments instead of running you down behind your backs."

"Paid us compliments!"

"Yes; he said you were such splendid game players that nobody expected you to use your brains much. And he said that even if you did know only about five or six hundred of the simpler words of the vocabulary, what did it matter? He didn't blame you—he said some men were just beefy, like you, and others were just brainy, like him. These things were arranged for us by Providence, he said, and if some were more fortunate than others it couldn't be helped, though the more fortunate ones ought to be sorry for the others, just as he is sorry for you. '

The brothers gaped.

"Sorry! Sorry for us! That mop-headed poetry grinder sorry for us!"

"Genuinely sorry for you, and I thought that was so kind and sweet of him," stormed Dulcie. "You don't deserve it. And I am over twenty-one, and I am going to have him here occasionally to tea, and I am going to study poetry with him; and if you don't agree to be gentlemen you can get somebody else to keep house and look after the servants—so there! And he's got I lovely hair and you've got only scrubbing brushes; and before you laugh at his velvet coat you ought to look at yourselves in your silly old baggy plus-fours and your ridiculous stockings and tassels and your perfectly awful little short jackets that make you look as if you had stolen your little brother's coats and your father's knickerbockers!"

And Dulcie, having reduced her brothers to sheer stunned and all-bestaggered silence, left them to recover as best they could, while she went out to study tiger blooms on the lawn with Mr. Haremain.

"I'm going to cut that comic bloke's hair if he has me arrested for it," said Tom Tressidder when, shortly after, he and his brother were sitting at a table in the golf clubhouse with the rough-hewn Mr. Bill Laffan.

Bill was a genuine young doctor, but without a practice at present. He was looking for one; indeed he had been looking for one for some time past. But evidently he had been looking in the wrong places. He seemed to spend most of his time on various golf courses which, notoriously, are not likely places in which to find a sound medical practice.

"I'm with you, Tom," affirmed Tim. "The bounder has got to be definitely discouraged. How about you. Bill?"

William looked wistfully at them. He was a very huge young man, buffalo-muscled and heavy with hard bone. But there was no brightness on his very rugged face.

"I'd give a couple of strokes off my handicap to take the blighter's scalp and stuff a cheap cushion with it, but Miss Dulcie would never forgive me. It's different for you—you're her brothers. But me—I'm nothing to her. It would do in my prospects with her absolutely."

The brothers saw that, for they prided themselves on being fair-minded.

"Yes, that's true, Bill. You'll have to stand out. Besides, it doesn't need three of us."

"How will you set about it?" demanded Bill Laffan, suddenly becoming extraordinarily keen.

"Oh, just grab him, and Tim can hold him while I run the clippers round his skull, I suppose."

"But, I say, perhaps that mightn't come off. He may call for help or something. There might be a frightful shindy and he might escape with all his hair on," objected Bill. "Besides it's a bit rough. Why be rough? You want to make a certainty of it without roughness. If you're rough Miss Dulcie will be too furious to see what a fool the fellow will look. But if you do it quietly, without a row, she won't have her attention distracted from the humorous side of it. Why, you—you men, dash it, the bounder'll look like a comic convict! I'll bet a bob his head is all lumpy and shapeless. These poets always have heads like that—speaking as a doctor. Do it, certainly do it as soon as you can, but do it quietly, gently. What I mean, clip the beggar without noise or fuss or roughness—and then let Miss Dulcie see him. That'll finish her infatuation—mark my words. If it's clothes that make the man. it's hair that makes the poet."

The brothers listened gloomily.

"Yes, that's all right, but he's not going to submit to the shearing like a tame sheep. Even the merest worm would turn," objected Tom Tressidder.

Mr. Bill Laffan leaned forward, lowering his voice.

"Look here, you men, I'll attend to that part of it. I'll give you a bit of a tablet to drop in whatever he drinks when your sister next invites him to have something at your place. Oh, nothing that's likely to hurt him—just a bit of a harmless opiate that will make him a bit sleepy for half an hour. He'll simply feel like a bit of a doze, take forty winks and wake up again feeling as right as rain, except maybe a bit chilly behind the ears."

"What a brain! That makes it child's play." agreed the Tressidder brothers eagerly. "We shall owe you a lot, Bill, if this comes off."

"If Haremain's hair comes off, you mean, ha, ha! I'm doing it because I consider it's my duty to try to save a sweet girl like Miss Dulcie from the clutches of any sonnet slinger, regardless of results."

So in an atmosphere of mutual esteem and good fellowship the pitfall was well and truly dug for the poet.

It was perhaps a shade on the rough side, as Tim Tressidder put it when, a little later, they dropped in at a local hairdresser's and by judicious negotiation hired a sharp and businesslike pair of clippers; but, he continued, it is impossible to judge a man's true character until one has seen him immediately after a close haircut. Bill Laffan had dilated somewhat on that aspect of the affair.

"If I thought that Miss Dulcie had the chap correctly weighed up in her mind I would not harm him or conspire to harm a hair of his head. But she has not—I'm sure of it. There's many a man wearing his hair long that would give himself away completely with it short. Many a man has kept himself out of jail by wearing his hair long and artistic; many a politician has kept himself in office by letting his hair sprout till he looked as if it was running to seed. Speaking as a doctor, I assert that a very large number of these famous men get their reputations only by concealing—with hair—from the multitude the fact that their cranial development is far below par and that they wear a pea on their neck instead of a full-sized head! No. If Miss Dulcie prefers this weird bird to me—well, it will about break my heart, but at least I'm a sportsman and I shall have to stick it. But what I do say and you two agree with me, I know is 'Let's have it fair.' Let the man be tested. Let Miss Dulcie have a chance to see the man as he is. If he stands the test, well and good. I say no more. But test him first; and the way to test him is to give him a haircut; and the way to give him a haircut is the way we've planned it."

Whole-heartedly the brothers had agreed, and when, duly furnished with the necessary equipment, they parted from Mr. Laffan, they headed homewards with lighter hearts than they had carried for many a day.

IF IT was with surprise, tinctured with suspicion, that Mr. Hamelyn Haremain observed a marked increase of cordiality from the brothers Tressidder next day, he was careful not to show either the surprise or the suspicion.

He had called in as was becoming his custom for a little tennis and a good deal of poetry with Dulcie.

Hamelyn was a blond youth with clear blue eyes and if its proportions had not been wrecked by the nimbus of yellow hair surrounding it a very good-looking face. A competent observer would have noticed that his mouth was not bad and that his chin might have been worse. He carried himself with the ordinary ease of normal youth and was looking quite decent in flannels. But the Tressidders had long since reached the stage when they could hardly see him for hair.

The brothers were sitting in deck-chairs on the lawn as he came in through the door of the long garden wall.

"Here's Love-in-a-Mist!" said Thomas under his breath. "Be civil," he reminded his brother.

They were civil.

"That you, Haremain? Sit down. Dulcie's slipped down to the town for something or other. She'll be back in a few minutes.'

"Thanks very much," answered the poet, his dreamy eyes on the guileful golfer.

"Topping day, what?" suggested Timothy with breeziness.

"Very topping," agreed the poet, his eyes traveling to Tim.

"Well, personally, I call it a bit too hot," demurred Tom, affably enough. "Too hot for golf. The links are bone dry and dusty as a gristmill. And, for that matter, it's dry work talking. What about a quick one? Look here, that's a brain wave. I'll tell you what, Tim, old son, we'll have a bottle of that prewar Rhine wine up. What was it? Forster Riesling. Topping good drink a day like this. What about it, Haremain?'

"An admirable idea," agreed the poet.

Tom having contributed the idea, Tim rose to contribute the labor of fetching and opening it.

"How's the poetry running?" inquired Tom blandly, and continued without waiting for an answer, "Tough work—very. Never did much of it myself. Bit prejudiced against it, in fact. Silly to be prejudiced. Pure prejudice. Leads a man to extremes rather, don't you think?"

"Yes, indeed," agreed Hamelyn Haremain feelingly.

"Yes. It may sound a mad thing to say—sitting here comfortably—but old Tim and I very nearly took a dislike to you, old chap, because you are a blighting poet. Queer, eh? Prejudice. But we saw the foolishness of it in time. So—er—that's that."

Hamelyn Haremain sighed.

"Yes. yes; one meets it on every hand, this prejudice. It is so—just as you say—and it is very sad, very shocking. It is pleasant to meet men broad-minded enough, like your brother and yourself, to tread such malign prejudices under your heels—most pleasant."

He passed his hand, rather a sunburnt hand for a poet, across his brow.

"Still one goes on. One—er—continues. We poets understand. They killed Keats; and Chatterton killed himself; but we—

"Still stick it, what I mean to say," finished Tom Tressidder, as Tim reappeared with a tray bearing three distinctly inviting glasses brimming with the Forster.

With a casualness permissible among three men of the world he put the tray on an outdoor table and passed each a glass.

"Well, cheerio!" he said in a rather excited voice.

For a few moments they sat in silence surveying first the empty glasses, then each other. If the poet noticed a certain slightly hungry stare growing in the eyes of the brothers he gave no sign of it.

It was drowsy after-lunch work, sitting on that warm, sunny lawn in a deck-chair.

The poet was the first to break the silence—in a dreamy voice:

"Yes—a fair, a fair and fragrant wine. Not in vain did the golden beams of a benign and beneficent sun caress and kiss each richly swelling berry in that vineyard on the Rhine! They wrought a good work, my friends, who filched with loving care the golden rays imprisoned in the grapes that grew to joy and gentle us this day."

"Certainly, certainly they did," agreed Tom Tressidder in a trembling voice. "By Jove, Harebrain, old chap, you've certainly got the gift of words!"

The poet seemed to ignore him. Even more dreamily he continued in slow, measured, drowsy phrases, leaning back with closing eyes:

"—to joy and gentle us this day. I praise—I hymn—the vine, the green and gracious vine—the tender, sun-kissed grape—the golden wine. Dark in the dusky shade the swelling bunches dream—dream—dream—" He paused.

"Why. the chap's as tight as a lord!" whispered the awe-struck Tim. "He's doing poetry in his sleep."

"Shut up!" hissed Tom, his great hand sliding stealthily to his pocket.

"—dark in the dusky shade the swelling bunches dream," continued the poet, languorously, "and perfectly fulfill themselves—beside the Rhineland stream. No, no. Bad, bad—Rhineland stream—damn bad. Try again. Sweet in the sheltering shade the sun-kissed—weltering— No. no. Not sweltering in the shade."

"Potty; absolutely potty," signaled the lips of Tim Tressidder.

Tom shook his head, watching the poet as a doctor watches a gas case at the dentist's.

The poet, sliding swiftly down into the deep well of slumber, tried again, in a somewhat different vain, muttering:

"'But I,' said the Grape, 'continue.' 'And survive.' said the Vine. 'Above the mounds of splendor I flourish, over the dusts of glory entwine.' Ruins—inheritors—grapes—a bottle of wine; Jerry's an—ugly fighter—but—he's delivered the goods on the Rhine—Rhine wine Grr-rr!"

It was rather weird, that dropping off into a little sleep, a little slumber; and had the brothers Tressidder been a shade less excited they might have argued something from that last curious expression—culminating though it did in a moat unpoetic snore which rimed with nothing, except maybe the growling of a watchdog.

Then did Thomas Tressidder arise, a baleful light in his eye and a gleam of cold steel radiating from his right hand—the clippers. "I'll have very last hair on his head," he said grimly, to! Get a move on, Tom-oh!

The clippers flashed like a playing of lightning about the frizzy head. Then as with a whispering secret sound they bit and burrowed deeper into the poet's shining thatch, they seemed to vanish and were silent.

Large dots and skeins of the yellow hair began to slide down the shoulders of the sleeping poet.

"Lord, what a mat—what a mat!" muttered Tom Tressidder as he worked the barbaric instrument. "Stick it in a bag—anywhere out of sight, Timmy. No need to let young Dulcie spot We'll tell her the blighter came here like it—as blind as a newt. He won't be able to deny it! Lord! There's a festoon of it for you!"

But Thomas was overly optimistic.

Dulcie saw—had seen—was seeing.

Lost, rapt, absorbed in their fell work, the brothers had not noticed the opening of the garden door, nor observed Dulcie enter, stop, stare, raise her hands, open her sweet mouth—then suddenly close it again and stand watching with a strange, rather guilty stare. She watched openly for a moment, then crept back through the door, leaving it open by no more than an inch. But through that inch a pair of blue-blue eyes watched the dastardly deed to the end.

Tom Tressidder worked swiftly and untiringly—for much golf had given him the wrists of a virile young gorilla.

Presently he stood back, wiping his brow, and surveyed all that was left of Mr. Hamelyn Haremain. Tim stood back with him, their mouths opened ready for the briefly contemptuous and derisive laugh which—somehow—never came.

The poet was shorn not within an inch of his life but certainly within a thirtieth of an inch of his skull—and it had wrought a change, an incredible change, in him.

Something had misfired in the great Tressidder scheme!

Hamelyn Haremain had dozed off a moderately good-looking but extremely effeminate seeming person. But Tom Tressidder had transformed him into a youth who could have posed with entire confidence for some of those old Greek sculptors—and that though, practically putting it, be was as bald as a toy balloon. The contour of the poet's head was perfect—the skull of a man with courage, philosophy and, possibly, genius. A fine head, a handsome head, a head that the hardest-shelled phrenologist would have fingered free and gratis for the sheer joy of it.

Now that the misleading hair was gone the Tressidder brothers dimly realised the full meaning of the word "brow." Hamelyn had it—a matchlessly curving area of it—quite obviously with something worth while behind it. A brow that got them guessing. The nose spoke for itself, pure-blooded Christian though Haremain was. A grand nose, a proud nose, a Greek nose. His fine firm lips were the lips of a warrior or a lover or of both—Dulcie knew best. And the bold chin was a man's chin—the chin of one who could be inexorable where that was needed, but tender and true and faithful as a mother when those qualities were called for.

The Tressidder brothers stared at Hamelyn, then at each other.

"Tim," said Tom with solemnity, "we've made a bloomer! That chap's a white man! I'm a damn fool, Tim, an you're a damn fool, and Bill Laffan's a blasted fool! I don't see how a chap that looks like this merchant can be anything but white/'

Tim nodded.

"He's certainly a fine-looking chap, Tom-oh!" he acknowledged huskily. "If I looked—Clarice would—"

He broke off abruptly, for the poet was stirring restlessly in his sleep.

Bill Laffan may have been a blasted fool, but he was not fool enough to give them a dope which had any long-lasting effects. Whatever the sweet William had given them to slip into Hamelyn's wine was undoubtedly to the point—but it was also brief.

The poet moved, murmuring something about "Blow, blow, thou whiter wind! Freeze, freeze, thou bitter sky!" or words to that effect, and his sunburnt hand fluttered aimlessly about his shaven skull. The sinewy fingers touched the skin, and the poet woke with a violent start.

"What the devil?" he said, and rose, running his hand urgently over and around his head. It made a rasping sound as it went.

"Good Lord!" he said, and stared at the brothers with eyes that were suddenly steely. "Who did this?" he said. His voice was not at all languorous and there was nothing of the lusciousness of the grape in it.

"I did, Haremain," said Tom Tressidder, rather white.

"With my assistance," added Tim gravely.

"It was a mistake—in some ways an error of judgment. I—I think I'd better apologise. Haremain," said Tom.

"I apologise also," said Timothy.

Cautiously the Greek god ran his hand over his head again, then stiffened, frowning.

"Fetch me a hand glass, one of you," he said sharply.

Meekly Tim went. It was no fun for him—or for Thomas but they were sportsmen and gentlemen, and you have to take your medicine where you find it, if you are one of these.

For many seconds Mr. Hamelyn Haremain stared at his handsome reflection in the glass—looted from Dulcie's room, as the excited and shining blue eyes peering through the garden door promptly saw.

Then with a long, long sigh, Hamelyn put the glass carefully on the garden table, slipped off his blazer and rolled up his shirt sleeves, taking one or two light, easy, flexing steps on the dry turf.

"I'm sorry, Tressidder," he said to Tom, "I'll have to ask you to put up your hands! Quickly!"

"I've apologised," said Tom, very slowly and painfully. It came hard, very hard, for poor old Tom.

"Yea, I know. I'm sorry—but it's not enough! You have done me a great injury!" said Hamelyn, his nostrils blown out.

Tom Tressidder let a sigh of relief like the sigh of a high-pressure boiler escape him.

"Good enough," he said, grinning a cordial grin at the poet. "I rather like you, Haremain. I'm with you old man, I'm with you all the way!"

He had better have said "some of the way," for although undoubtedly a fine golfer he was but a very moderate boxer, as a masterly welt just above the belt a few seconds later, caused him to suspect.

"Rather low!" he grunted chidingly.

"I think not. Try a higher one!" snapped the poet, and passed it to him on the jaw.

"Gad!" went Tom groansomely.

"No, no; Haremain," whipped the poet; and, so, went for Thomas, beginning with the solar plexus. He called on that spot twice, swiftly, with diabolic skill, then worked his way upwards, played crisply on the point for a while, then concluded the worthy Tom with an anaesthetic under the heart.

He went down across the tennis court—an obvious fault—and the poet dropped his hands for an instant.

A bare-armed Tim touched him gently, gravely.

"There's still me, old son. Sorry to seem to press you. If you'd sooner wait—just as you wish."

"No, no," said the poet. "Let's get it over. But how about Tom? Is he—"

"Tom—oh's a good old bullock. He's all right. Come on, old chap! Good luck to you. But I'm after your blood, Hamelyn!"

This was right—he was a long, long way after the poet's blood!

He was to Hamelyn what the punch ball is to Dempsey.

The shining eyes at the garden door went dim as Brother Tim completed the double fault across the tennis court—dimmer still as the poet, after a glance at the sorrowful brothers, lapsed into a chair and buried his classical head in his hands.

Then the door swung wide and Dulcie hurried in, her eyes sparkling with tears.

"Oh! Oh!" she said! "How dare you!"

The poet looked up.

"But—but—they gave me some wine that made me sleep, and then they—cut my hair—like this, Dulcie!"

"Well, you ought to say thank you to them for that—not hit them so!"

"Not hit them? But, Dulcie, please Dulcie, don't you like poets who—who look like poets. I—I mean—long hair and—and all that sort of thing? I heard—someone said that you did. When I first saw you—oh, months ago—I went away and grew all that that fearful fluff for your sake."

"Let me see!"

Dulcie stood back, screwing up her eyes—but not so tightly that a pale, bright diamond or two failed to escape them.

She stared for a long, long time. Then slowly a splendid pink flush veiled the glorious ivory of her face and she came to him, crying softly.

"Dear, my dear. I was ashamed they—cut it off but, oh! I am glad, too," she whispered. "You see, I thought you liked it that way."

"Dear, my dear. I was ashamed they—cut it off but, oh! I am glad,

too," she whispered. "You see, I thought you liked it that way."

"No, no, Dawn—dear little Dawn I hated it!" He was enwrapping himself about her.

Dulcie sighed interminably. "So did!"

"So you did. I was so stupid not to guess."

"I hid it. But how were you able to defeat Tom—and Tim?"

"I—I hardly know, little one. I was middle-weight boxing champion of the Flying Corps two years. And when I felt my short hair, the thought of boxing seemed to come back to me!"

"Ah! Ah! That accounts for it, my darling. You and the boys will be such friends."

"Yes, yes."

The boys were glaring at a head that was bobbing jerkily over the side wall the head of Bill Laffan.

Grateful for this diversion from a very natural embarrassment they went across to the head.

"No good, Bill," explained Tom briefly. "It's been a failure—a shockin' bloomer. Buzz off, old son!"

The head's mouth fell open.

"What, me? Me buzz off?" it uttered.

"Well, look for yourself!"

The head of William Laffan turned, its eyes fixed on the rhapsody in the deck chair. For a moment it hung, fixed.

Then it murmured wanly: "Oh—righto. Thanks, I can take a hint with any man!" and disappeared.

Tom looked at Tim.

"Hamelyn's a white man, I think, Timmy."

"As white as wool, Tom-oh!"

"Better go and tell 'em so, what?"

"You've taken the words out of my mouth, Tom-oh!"

"All right, old son. Come on, then—by the left "

And so went across to Dulcie and her man—good chaps, maybe a little congealed behind the brow, but, still, good chaps.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.