RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

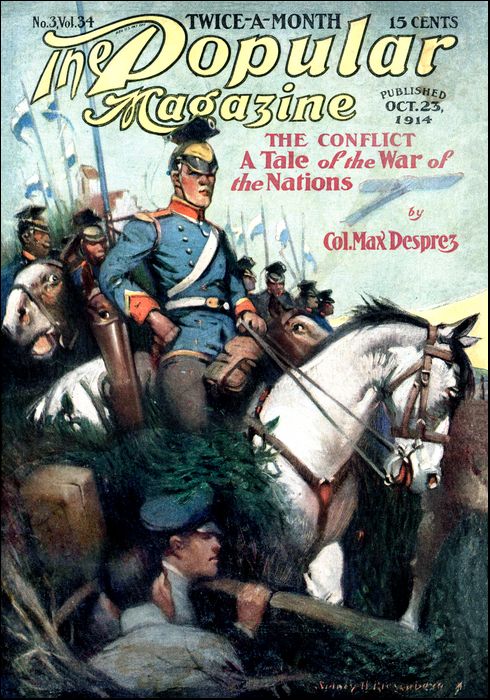

The Popular Magazine, 23 October 1914 with "Purty-Fer-Nice"

AS it was told to me at divers times and in various places, by the old foreman of the Lovelock Ranch, I shall give you the story. If you are a moralist you may discover in it a nice problem in ethics—and you may not. If you have known such a man as the foreman himself, you may appreciate his point of view and sympathize with his problem, and perhaps you will call him an honest man when you are done with him. A prophet once told a lie to save himself and his friends, and God smiled and let it pass—seeing the prophet was saved. And when the foreman of the Lovelock told me his story, I also smiled and liked him better for the thing he had done.

Picture him a bit stiffened, so that he got up with his palms against the small of his back—that was lumbago, that gave him "cricks." Picture his face seamed and tanned and a bit shriveled—that was his range diploma, hung above the wrinkled collar of his shirt to prove he was a friend of the sun and the sage and the whooping west winds. Picture his squinty eyes a-twinkle and his head cocked sidewise and a cigarette hanging precariously on his under lip—that was his shrewdness measuring my humanness to see if it was big enough to take hold of the real bigness of the story. Picture his legs bowed—that was from the saddle. And if you can hear his voice with the calm dispassionateness of one who has passed so far along the trail that he can afford to smile at past prejudices, and with the chuckling note to prove he saw the humor of them, I think you will have a fair idea of the erstwhile foreman of the Lovelock. And so he may tell you what he told me, about Purty-fer-nice—and that, if you please, was the only name he ever called her. I don't know what her first name was; I never heard it.

DO you know, I've got a sneaking notion that folks back East are just as benighted and just as narrow and just as pig-headed as us boneheads out here in the sage, that ain't supposed to know anything but riding and roping and shooting out the lights in saloons and making tenderfeet dance when they don't want to. I may be wrong, but I ain't never found it out if I am. If I was going to make a break for the tall houses I'd try and git on a street car without grabbing for a horn to swing on by, and remember to keep my knife outa my mouth and my feet offn the table; and I'd leave my chaps and spurs in the bunk house till I got back. I'd play the game the way they play it, as near as I could. And I wouldn't be too swell-headed to take a few pointers if somebody wanted to hand 'em out.

But a lot of folks come out here from the East and try to work us over so we'll line up with what they've been used to. That's the point I'm getting at. They don't give a darn about conditions being different. We've got to line up to their chalk mark, or we don't make any kind of a hit with them. They don't stop to think that our environment produced us. They don't take into consideration, for instance, that most of us live right under our John B. Stetsons eighteen hours outa the twenty-four, and that we live with both hands full most of the time, so we can't unload and take our hats off if we happen to meet a woman unbeknownst. Them's the women; they call you a low brute if you meet them any way but bareheaded—at any rate, Miss Purty-fer-nice called me that.

First time I seen her—I'll never forget that if I outlive every tooth I got in my head—I insulted her till she was plumb aching to see me suffer, which I done. I'll tell yuh how the play come up; and, mind you, I ain't so narrow but what I can see her viewpoint. What made me sore was that she couldn't see mine. Long as she lives, I reckon, she'll hold it against me, whereas I don't hold any grudge atall. That goes to show I've got a right to call them Easterners narrow in their views; she ain't the only one; they's plenty more where she come from that's wearing the same brand.

She was teaching school over by Cottonwood Creek. Boarded at the Miller Ranch and drove to school every day in an old buggy and that white horse Jim McGuire used to own. You know the one I mean—the one that piled Bobby into the bobwire fence that Fourth. Well, Miller got hold of him.

He got stove up in the shoulders and Miller kept him for the womenfolks to hack around with, and so this schoolteacher, she drove him to school; couple or three miles it was.

I was handling the lines on the Lovelock then. I wasn't so stove up, though, and I had more hair and more teeth, and I considered myself in the running when it came to womenfolks, and didn't back down from nothing I met up with in the trail. Horses, whisky, hard work—they was all welcome and met with a smile of honest joy. I ride around all three now'days.

Well, I was coming out from town with a load of lumber and bobwire. It wasn't my job, but the fellow that went in after the load leaned over the bar an hour or so too long, and got in a fight and was licked. I left him laid up for repairs in Jack Moore's back room, and took the team out myself, leaving my horse for Scotty to ride when he got able. He was a good man, and we needed him on the ranch, so I treated him white.

We had a new horse that we was working that day. Big, shiny bay that I got stung with—I admit it. Johnny Lovelock, he came to me and asked me what I thought about the bay, and I looked the horse over, helped hitch him up, and drove him around the ranch, and told Johnny to freeze onto him. I admit it, I was plumb fooled on that animal. Hadn't a blemish on him; had good life and style and was gentle to handle. And seeing Johnny was trading off old Goodeye, it looked like pickings. I drove along easy—Scotty's flare-up had kept me kinda late in town—and thought what a good trade me and Johnny had made; me, because Johnny never went aginst my advice but twice in his life.... Them times I'm going to tell about.

I was feeling good. I'd had a shot or two myself—just enough to make my many virtues stand out prominent before my admiring contemplation, and my faults wizzle up till they needn't be dwelt on. I guess maybe you know the feeling. I was tickled to death to realize what a helenall good man I was, but I wasn't drunk. Nobody—not even a wife, if I'd had one—could have accused me of not being sober. I just felt good and satisfied writh myself.

Not to be too lengthy on the preamble, I got to the foot of the hill just the other side of the Cottonwood schoolhouse, when I come out of my pleasant musings. There was a chuck hole there; nothing to speak of—just a chuck hole, and an uphill pull to git out. I was admiring the sunset, and the team was plugging along steady as sheep, so I didn't see this hole, and let a wheel drop into it. Horses stopped, and I chirked at Bell, and she went into the collar—Bell was a good, true puller; she almost made it alone. But she couldn't quite cut the mustard. The chuck hole was on Prince's side.

Prince—say, I feel like cussing now when I think of it! Man or beast, I do most mortally hate a quitter. Prince was like lots of folks I've had truck with—the meanest kind there is to deal with; Long as things went smooth, he was fine and dandy; git in a pinch and he'd fly back. Balked right there, and it getting sundown, and me ten miles from supper and three from the nearest ranch. Oh, it wasn't a real story-hook kinda misfortune. There wasn't any howling blizzard, nor any cold rain—it was kinda spring weather that makes the curlews and meadow larks happy and sets 'em planning about where they'll build their nest this year.

You know how it is, though, when you're awful contented—whisky content—and something goes wrong; you git a jolt that throws you plumb to the other extreme. I got mad. A balky horse always makes me mad, and I was all the madder because I'd been crowing how me and Johnny had stung old Jimpson on that horse trade.

Pull? That bay horse was so scared he might accidentally pull that wheel outa the hole that he set on the double-tree—except times when I'd lift him off it with the whip, and then he'd sit and up a while on his hind legs till he got tired enough to set down again.

Well, I was setting up there calling him names and gitting madder the more I called him, when I seen a shadow crawl up alongside the wagon and stop. This was a horse's shadow, and I whirled around with my mouth open, ready to swear some thankfulness that help had come—and I seen it was the schoolmarm driving home from school and looking like she'd stirred up a polecat's nest inadvertant. Shocked? Wow-w!

I guess maybe my voice had carried my language quite a piece down the road; I got good lungs, and I was purty mad. And I guess my face was purty red when I seen her. And then I remembered that I hadn't been blaggarding none—a man hates like sin to be caught at that—but just damning things fast and furious, and I felt better. Any woman can excuse a man cussing a balky horse, I should think. If they can't, they'd oughta be caught in a chuck hole themselves with supper ten miles off and night coming on, and learn Christian charity.

That old white horse stopped dead still and commenced to switch his tail contented. You know how it is out here; horses git the habit of stopping when they meet anybody in the trail, because folks have to be purty mad or after the doctor or ahead of the sheriff when they won't stop long enough to pass the time a day and show they're human, anyway. Schoolmarm clucked at him like a hen partridge, and shoved on the lines—you know the way most women drive a horse!—and tried to pass me up like a white chip in a dollar-ante game. But old White never budged; he knowed his training better than she did, and I cut in with a polite how de do, and asked her would she please tell Miller, when she got home, to come with his team and help me up the hill. That wasn't much to ask, you'd think—just to give a message for me when she got to where she was headed for.

I guess you've seen women like her. She stood about five feet tall, maybe, and weighed about as much as a sack of oats. She had on a white dress and white slippers and a white hat with thin stuff bunched up on it, and a gold chain around her neck with a gold cross the length of my thumb hanging down like a fancy martingale. She had pale-blue eyes and freckles purty much covered up with powder, and she was driving with white silk gloves on that come up over her elbows and showed a ridge on her arm that I took for a bracelet as big around as a harness ring, and bunches on her fingers where she had rings. She wore a thin white veil that didn't do no good, far as I could see, but git in her mouth when she went to talk—oh, you've seen 'em back East a-plenty. Out West they don't belong, somehow. Her neck was about as big as my wrist, here, and about as long, and her head was tilted up like one of them dolls in a Christmas-store window. That's how she looked.

She puckered up her mouth and says: "I refuse to carry a message for any man that curses poor dumb animals and does not show enough respect for a lady to remove his hat when he speaks to her in the road." And she shoves on old White's lines and tries to drive on past me as haughty as she feels.

Now, I'd been as polite as circumstances and my disposition would let me be. One of our own women, that's been raised out here, would have hit the trail for help, or else offered the use of her horse if he was a good true puller, or looked sympathetic, anyway. She mighta laughed—women generally do when a man gits in a fix like that—but she'd 'a' done what she could to help out, and she wouldn't 'a' blamed me none for cussing that horse. I'd said how de do to this lady, and I'd looked ashamed of myself fer swearing. But I didn't drop whip and lines to lift my hat to her, and so I was in bad from the first jump. Think of a woman that wouldn't deliver no message because I hadn't took off my hat to her, and had swore when I never knew she was anywheres around!

"Looky here," I said to her, kinda tart. "It ain't going to hurt you none to tell Miller what I asked you to tell him. You're headed for the ranch, I know for a fact; I know that old horse," I says, "and I know all Miller's folks, and you ain't one of 'em. You're the schoolmarm that boards there, ain't you?"

She gave another partridge cluck to old White and pinches in her lips, and then has to twist 'em up to git the veil outa the way so she can talk. "I object to being called 'schoolmarm,'" she said to me, like she was telling me why I had to stay in at recess. "And I shall not deliver any message for you. I have no sympathy for any one who uses curse words."

That made me sore. "Well," I fired back, "drive on, then, Miss Purty-fer-nice, and git over the hill as quick as you can. Because what you heard accidental ain't a commencement to what you'll have to listen to if you stick around here. I'll give you two minutes," I said to her, "to git outa earshot; and then I'm going to cut loose. I'm in a helenall fix," I said, "and I'm ten miles from supper and hungry as a wolf. And," I said as sarcastic as I could, "don't worry none about the sympathy, Miss Purty-fer-nice. I guess I'll live just as long without it. You better git a move on—them curse words is coming; I can feel 'em boiling up inside of me."

Say, she was sure hostile then! She commenced to cluck and slap old White on the rump with first one line and then the other, and when I asked her should I give him a cut with the whip she turned red as a beet, and says, "No, you needn't!" like she wanted to bite my head off. "I never seen such a low brute as you are," she says; and got White going, and then drove off up the hill, and never looked back. I'll bet she was madder than what I was—and that's going some.

She didn't carry any message for me, anyway. I'll say one thing for Purty-fer-nice; she always stuck to her word, and if she ever told you flat-footed that she wouldn't do a thing, you could bank on it not being done. I know I kept looking up that hill while I was unloading the bobwire, kinda expecting to see Miller heave in sight. But he didn't show up, and so I had all the fun of taking off half my load, prying the wheel outa that chuck hole, backing up the wagon—mostly by hard labor on my part—loading up again, and persuading that new horse to help Bell take the load up the hill.

I done it, a-course; there wasn't any quitters on the Lovelock then, except that horse. And I kept my mouth shut when I got to the ranch, and never told anybody but Johnny about the new horse being balky. So, using good judgment and not saying anything, we got rid of him all right. Johnny he drove to town with Prince and the light rig, and let the feller that owned the livery stable coax him into trading for that big roan we had till the outfit was sold out. So we come out all right on the horse, after all. The roan was a jim-dandy on the ranch, and seeing he had a contracted hoof Johnny got some boot on the deal.

Well, I told Johnny, as I said, about me gitting stuck in that chuck hole. It tickled him to death, the way that schoolmarm called me down, and what does he do but just naturally hunt trouble, gitting acquainted with her and pumping her about me, just to see what she'd have to say, so he could devil me about it.

It was at a dance he done this. All us fellows went, a-course, and first off I spotted the schoolmarm, all in white, with her big bracelet sliding up and down her arm and her big eyes sizing up the layout solemn as a preacher and about as disapproving, and her hair pompadoured up to the last notch and her waist squeezed in till you could buckle your hatband around her easy.

"There's Miss Purty-fer-nice, Johnny," I said to him, soon as we was inside. "Over there by the organ. Yuh want to ride away around her, son, 'cause she's down on human men like a wolf. Don't let her git you the way she got me—and call you a low brute just because you're a live male being and no angel with wings." And that done the business. While I was gitting a pardner, he loped right over and got old lady Miller to introduce him.

He claimed afterward he just done it for a josh, to see what she'd say about me; and if he come anywheres near telling the truth, what she said was a-plenty. He tried to git me to go over and git introduced and square myself. But I never had to hunt long or hard for pardners in them days—well, I don't yet, far as that goes, when I take a notion to dance—and I told him I hadn't lost no schoolmarm. So I never did git acquainted with her officially, as you might say, all that spring and summer. I got into the same set with her once or twice that night, I recollect, and when it was "balance, swing," I swung her with the ends of my fingers; and in the "grand-right-and-left" we walked around each other without touching. That goes to show how bad we was stuck on each other.

Johnny, he was different. I always thought, and I think now, that he done it for devilment at the start.

He called her Miss Purty-fer-nice, same as the rest of us, and he kinda grinned whenever he saddled up and rode off with his town clothes on, like it was all a josh—his going to see her about once a week. He never said nothing against her; Johnny Lovelock wasn't that kinda man; he'd 'a' licked anybody that done anything but just plain, harmless joshing about a decent girl, and he wasn't the kind to make remarks about any girl he called on. But looks is plain talk, and can't be repeated; and Johnny, he gave me to understand right along that he felt the same as I did about the schoolmarm, except he could play the game her way and kinda enjoyed doing it once in a while. She wasn't popular, anyway, and I guess Johnny was about the only feller that went to see her atall.

Oh, yes, I know schoolmarms are always heart smashers in storybooks; you can take a girl from the East and bring her out West to teach school, and let a cow-puncher meet up with her in the trail, and you've got the poor devil's heart roped and tied down in about three-fifths of a second. But I never seen it work out that way many times, except on paper.

Men ain't going to fall over each other being attentive to a girl that goes along with her nose in the air, and teaches school in white dresses and white slippers, and has powder on her face so thick you could write your name on her nose with your finger. A feller feels like he's got to watch his grammar, and be sure he don't set down anywhere while she's standing up, and all that junk. And that's wearing on a man that ain't broke to it. It's like taking a range horse and trying to work him with one of them overhead check-reins drawn tight as a fiddle string. Town horses git used to 'em, and town men git broke in to the parlor game; but it's hard on prairie men and cayuses to be checked up too high—they're liable to bolt or kick over the tongue or something.

Took her about six months to rope Johnny in, and she wouldn't have done it then, I guess, if he hadn't happened along with her mail the time she got word her mother'd died. Johnny was always a sympathetic cuss, and I take it Purty-fer-nice shed some tears on his shirt front before Johnny give in. Don't matter, anyway, how she got him; she done it, and that's what puts the kibosh on many a good feller. It ain't the woman trying to git him—it's her succeeding that does the harm.

She finished up the term of school, and then she didn't have any place to go—being left alone when the old lady cashed in—and so Johnny married her and brought her to the ranch.

Sa-ay—a woman sure does make a lot of difference on a ranch. Take the best of 'em, and they change things. There ain't the freedom, after a woman hangs up her hat in the house. And I wonder if you've got enough imagination to realize what it was like to have Purty-fer-nice at the Lovelock. And Johnny married to her. And all us fellers hating to quit on account of Johnny, and hating to stay on account of her.

Never changed a hair with matrimony, she didn't. It was Johnny that had to do the changing; and the ranch, and us poor devils on it. You've seen women like that, maybe. Stand-patters—and standing on a pair of deuces most generally. That wouldn't hurt nobody but them, in cards; but in matrimony it's hell.

Take Johnny Lovelock, as straight a young feller as there was in the country; honest, big-hearted, square—what does she do to him? Well, I'll tell yuh. There was smoking—he'd smoked ever since he was a kid in short pants; if it hurt him it sure didn't show on him, for he was over six feet in his socks and could bulldog a big, husky three-year-old steer, and had nerves so steady he was the best rifle shot on the ranch; no wild West hero, you understand, but big and strong and healthy, and liking his smoke with the boys in the bunk house about as well as any of us. Well, Purty-fer-nice, she starts in to work him over according to her little sewin'-society pattern. She didn't approve of tobacco, so Johnny had to quit. Say, it was plumb pitiful to see him watch a man roll a cigarette, and try and not let on he was crazy hungry for a mouthful of smoke.

He took to chewing tobacco, down to the stable; he could rense out his mouth afterward and she wouldn't git wise. It gave him heartburn, but he chewed along for a month or two, and then she found part of a plug in his hind pocket.

I dunno for sure, but I heard she made a helenall row about that. She hadn't been annoyed, mind you, by no tobacco breath, or any smoke, or anything like that. She'd been saved from any disagreeableness whatsoever, and till she found that plug she never suspicioned that Johnny ever got within rifle range of tobacco. But the mere fact that he was gitting some little comfort outa something she didn't like or approve of, started her working the martyr game for all she was worth. Allie, the girl she had doing the work, told us fellers that she bawled around the house worse than a calf in weaning time.

So Johnny, he quit chewing for a while. He was trying his darndest to play the game; I know that. But Purty-fer-nice, she kept accusing him of using tobacco on the sly—so the girl—her name was Allie Brown—told me.

I guess there ain't anything grates on a man like being forever nagged about something he ain't guilty of. Johnny was purty game; he stood that for a couple of weeks or so, and then one day he flew the track. I guess she'd been throwing it into him a little harder than usual, maybe. Anyway, he come down where I was mending harness in the blacksmith shop, and he looked like he could bite a tenpenny nail in two.

"For criminy sake, Frank, gimme a smoke!" he says to me, kinda gritting his teeth over it. I never said a word back—I ain't the kind to lip in between married folks—but I handed out the makings, and he set down on the anvil and smoked three cigarettes without stopping and without saying a word till he was done. "Thanks," he says to me then, and handed back my papers and sack of tobacco, and got up and left.

I was kinda worried about Johnny. Marriage was giving him the worst of the deal, it looked like to me. I went to the door and looked out to see where he was headed for. And while I rolled and smoked a cigarette I seen him saddle up and ride off. Purty-fer-nice, she seen him, too—you know how the trail kinda angles past the house, at the Lovelock—and she came out on the porch in her white dress and white slippers, and hollered after him. You know how some women call folks; kinda chirpy and breaking a name in two in the middle. "Oh, Joh-on!" she chirps—but Joh-on never looks back. "Oh, Joh-on!" she chirps again, and he puts the steel to his horse and hides himself in dust.

Honest, I was kinda sorry for Purty-fer-nice, too. I didn't have any use for her, and she didn't have none for me. We never come within speaking distance if we seen each other in time—but she looked awful little and lonesome there on the porch, watching Johnny ride off mad; I knew he was mad, just as well as if I'd heard him cussing four ways and backward; and I knew he was mad at Purty-fer-nice, just as well as if I'd heard 'em -scrapping. And I was so sorry for Johnny I used to wake up in the night and swear about the way he'd handed himself the worst of it by gitting married. But I was sorry for her—honest, I was.

She stood there till he was outa sight, and then she took her handkerchief and wiped her eyes, and wadded it up and held it aginst her mouth like she wanted to cry and wouldn't. Then she seen me standing in the door of the blacksmith shop. I throwed away my cigarette and ducked back outa sight—that's the way she'd changed things at the Lovelock! Got us so we ducked, by criminy, when we caught her looking at us—and went back to riveting a holdback strap on the light harness.

In a minute here she was in the door of the shop. And she looked littler and lonesomer than she done before; and her eyes was red and her nose was red and her cheeks was shiny and she'd forgot to repair the damages with powder—which convinced me that she felt bad, more than if she'd spent an hour telling her troubles. When Purty-fer-nice plumb forgot her looks, you could gamble she felt purty blamed tough.

She asked me would I hitch up old Mollie for her. I said I would, and started immediate to go and do it. And just as I was going past her she give a little ketch of her breath and says: "Do you—know where John was going?" Just like that.

I said: "No, I don't know as I do—but I guess maybe he was going to see about the fence in the big field where it's down. He was saying something about it."

That was a lie, a-course. There wasn't no fence down in the big field, and anyway the big field lays off the other way. If I knowed men atall, and Johnny in p'ticular, he was headed for town; he was going with the bit in his teeth—and when a man bolts he don't generally ride off somewheres to set on a hill and admire the view.

I didn't tell her that, a-course. I knowed Johnny was being broke to stay on the ranch unless he had good and sufficient reasons for gitting off it—and then, as a nice, tame husband, he was expected to say where he was going. what he was going to do when he got there, when he would git back, and all about it. And if it was to town, there was more red tape and most, generally a list of things wrote down in pen and ink for him to git. So I know she'd do less crying and less nagging maybe when he got back, if she didn't know just where Johnny'd gone.

I ain't going to give a complete history of their private affairs; I don't know as I've got any license to, seeing it was mostly guesswork on my part. But that's a sample of the way things commenced to go with 'em; and when a couple begins that way within two months after the wedding, it stands to reason they're going the downhill trail for fair, unless one or the other has got sense enough to see where they're heading to and pulls up, or they just naturally think so much of each other that when they've both fought to a standstill they turn around and get to pulling together again.

Johnny hadn't never had a boss over him in his life, and he wasn't the kind that took to it. He come to me every day after that, and begged the makings off me. She'd done that much in just about six weeks—she'd make him cheat at the game. One day he got kinda ashamed, or else didn't give a darn—anyway, he went up to the house with a cigarette in his face. Allie, she told me afterward that Purty-fer-nice went four days without speaking to Johnny, and slep' in the spare room while the row lasted. I know Johnny went off to town and stayed a couple of days, and come back with a bottle in his pocket and a lot more than was good for him on the inside of him. And that's something he wasn't in the habit of doing before he got married.

Well, I butted in then and told Johnny about where to head in at. I didn't have any use for Purty-fer-nice, but at the same time I couldn't see where Johnny had any call to go to the dogs just because a pin-headed female woman like her didn't have no sense.

I told him that and a lot more—only I didn't say nothing about his wife lacking brains. I put it kinda broad and general. I said to him: "Johnny, a married man's got a right to play fair. You never come home half shot when we was a stag party at the Lovelock, and it ain't honest to come like that to your wife," I told him. I said: "You want to cut out all this running on the rope, Johnny. You're snubbed up purty short, but it's up to you to gentle down and not fly back on the lead rope. You went into the corral," I said, "of your own accord. I tried to haze yuh back onto the range and you wouldn't go. Now," I said, "show us you're a man, anyway, that ain't going to cheat when a lady sets into the game. You always played fair," I said, "with men. You're a darned poor specimen," I said, "if you can't play fair with a woman."

Then I handed over the makings, and he looked at me kinda funny, and give a little snort, and rolled a smoke, and give me another funny look.

"You needn't to call me an inconsistent cuss, because I ain't," I said. "Cutting off your tobacco," I explained to him, "is unconstitutional, and don't come under the rules of the game. You gotta have a smoke now and then or you ain't fit for a bull calf to git along with," I told him. "But whisky ain't necessary to your general health and disposition," I said, "and you want to cut it out. And the same with poker."

That last was straight guesswork on my part, but it hit the mark, all right.

Johnny, he scowled at me a minute, and says: "Who told you I was gambling?" And when I just merely looked wise and said nothing—having nothing to say—he says: "I dropped seventy-five dollars—I suppose you heard that, too."

"Well, you want to cut it out," I said, like I'd been wise all the time. "You got a wife now to look after."

That was as much as I dared say—and a whole lot more than anybody else coulda said to Johnny. It helped, maybe. I thought it did, because Johnny, he stayed home for a while, and it seemed like he was trying awful hard to live up to his wife's rules. He'd go two days, sometimes, without coming around for a smoke, and he wouldn't come near the bunk house, which was another thing Purty-fer-nice set down on. She hated like sin to have him come and set talking to the boys, or play a game uh solo or anything, and she'd always act abused, Allie told me, when he'd spend half an hour or so down with us.

He'd stick to Purty-fer-nice and go without smoking and toe the mark and shave every morning and set and listen to her read poetry to him—Allie said she seemed to think she'd got- to educate Johnny up to her level—and take her buggy riding around to places where he didn't want to go; and she'd think, I guess, she'd got him tamed proper. And then he'd break out and spend a whole evening with us fellers in the bunk house, and let on like he never heard when she'd come out on the porch and call, "Oh, Joh-on" along about eight O'clock. Us fellers called it ringing the curfew. And he'd smoke till he got dizzy-headed, and go to town and gamble, and have the hull darned ranch worrying about his morals.

Some of the boys got plumb disgusted with seeing Johnny spoiled that way, and quit. But I stayed with him. It looked to me like Johnny needed friends more than he'd ever needed 'em, and that the supply was dwindling.

#####Purty-fer-nice didn't have much company; I don't believe there was more than four or five women at the ranch all summer, and most of them come to see Allie. A-course, I was gone the biggest part of the time, but Allie, she told me. She said Purty-fer-nice told her that no lady would use slang the why them rancher women done, and she said their grammar was awful and their manners was crude. And she said they never read nothing but the county paper and trashy magazines, and so they couldn't talk about nothing except their narrow little lives and each other. She said she was plumb tired of hearing about the internal ailments of them women. Naturally they didn't wear the trail out to the Lovelock visiting her when she felt that way about 'em.... But all that was hard on Johnny.

Johnny was the kinda feller that could ride to a ranch at any hour of the day or night, and be fed pie and joshed and have his hat hid so he'd have to stay for a meal or two or all night, maybe. You've seen them kind. All the kids running up the trail to meet him, and the women actin' like the angels had give 'em charge over him, and they was anxious to do the job proper. It was plumb pitiful, to me, to see how the Lovelock trail was left cold, and how Johnny, he never went around places no more just to be friendly. Purty-fer-nice wouldn't visit, because the women quit coming to see her; and if she wouldn't go, Johnny wouldn't. See how it worked out?

And yet at the same time I couldn't help feeling kinda sorry for her, too. She meant all right, I guess. She simply didn't have sense enough to see she couldn't bring out a bunch of Eastern rules and make the West follow 'em. She wouldn't 'a' thanked Johnny to move back East and try to work her and all her friends over to suit what he'd been used to; you see, don't you?

It was plumb foolish. We're different out here, just because we have to be. The country and the life we've lived has made us different. And no little, slim, hard-as-nails schoolmarm could work us over. All she coulda done was to fit herself into the life somehow—or else git out. She liked Johnny, I guess—but she plumb ruined him, just the same; and she done it in ignorance and with being too narrow and too strict and too darned sure she was right always, and in not being human enough.

It was gitting close onto spring when the big blizzard hit the sage country. Johnny'd gone to town horseback the day before, and he'd went because he was mad. I don't know just what the row was about that time—Allie, she didn't know, for she was out in the kitchen, washing, and both doors was shut when the big set-to took place. But I guess it was the same old story, most likely; Johnny had probably did something contrary to the book of etiquette, or had maybe said something crude. Anyway, he went off mad, and he didn't come back that night, nor the next night; nor never.

It was the next day that the storm hit us all in a heap. Forenoon had been warm and sunny—but kinda weather-breedy and hazy and too still. Then she come with a Whoop, along about 'leven o'clock. Say, she was sure a real one! Snow like flour, and so thick in the air you couldn't breathe scarcely, nor see, either. I was down to the creek chopping out a water hole when she struck, and I know I had a whale of a time gitting up to the bunk house. That's how bad it was, five minutes after it commenced. There didn't happen to be nobody but me and a feller we called Missou' on the ranch that day—and Allie and Purty-fer-nice, a-course. In the winter us fellers et up at the house to save the price of a cook—we et in the kitchen. And we

went when we was called and beat it before we'd got our last mouthful swal-lered; it wasn't comf'table at the house with Purty-fer-nice liable to walk into the kitchen any minute and give us that school-teachery look of hers that made us wonder if our ears was clean or she'd saw us put our knives into our mouths.

Allie, she hollered, right after I'd got to the bunk house, and I went over. I thought it was kinda early for dinner, but I thought maybe she was outa wood or something. It was Purty-fer-nice—she was sick, and Allie was plumb scared to death, there alone with her. She said Purty-fer-nice was worried about Johnny. She said she'd been kinda sick all forenoon, but she was gitting worse right along, and Allie thought somebody oughta go fer the doctor, or something. And why in time wasn't Johnny Lovelock home where he belonged? And when did I s'pose he'd show up ? And couldn't I do something? You know how some women are; they don't think much of a man till things go wrong, and then they expect him to go to work and hog-tie fate and all the furies and put a ring in their noses so they'll lead.

Well, I took Allie by the arm and led her over to the window, and showed her the storm, and asked her what chance she reckoned a feller'd have, going fer a doctor. Or what chance Johnny had of gitting home. Or what in blazes she expected me to do, anyway. "You see," I said, "you can't see nothing but snow. You can't see the bunk house half the time. Stand outside by the corner of the woodshed, and 111 bet a month's wages you can't hold your eyes open, or breathe facing that wind. And," I said to 'er, "what the blinkin' blue blazes do you think any human man can do aginst a storm like that? If I could git to town," I told 'er, "I'd go a hell popping. But I know what I'd be up aginst if I tackled such a fool thing as riding ten miles aginst that combination."

And then Purty-fer-nice, she called out in the kitchen: "Oh, Joh-on! Is that you, John?"

Sa-ay, did you ever notice how just the tonation of a voice can make the cold chills run all over yuh? I dunno why it was, but I got that way all of a suddent. I just stood there and didn't dast breathe, and I felt cold crimples going down to my toes and up to my hair. I dunno why. I hadn't commenced to worry about Johnny; I just simply told myself he was in town, and let it go at that. And Purty-fer-nice's voice didn't sound any different from what it always sounded, unless, maybe, it was kinda anxious and kinda wishful-like.

"Oh, Joh-on!" she chirps again, the way women like her call a name. And in a minute she says: "Allie, is my husband with you?"

"No, ma'am," says Allie, like a scholar in school, "it isn't nobody but just Frank."

"Isn't—anybody," Purty-fer-nice corrected her, like she was hearing the last class and was tired and wishing it was time to let out school.

"Yes, ma'am, it isn't anybody but Frank," said Allie, like she was thankful it wasn't no worse.

I started outa the house on my tiptoes and with my gills working for more air. But Allie, she yanked me by the arm, and says: "You come back here, you yeller streak ! Yuh think I'm going to stay alone with her?" And so I stayed. Nobody'd ever accused me of being yeller before.

Well—folks sometimes have to go through things they don't never feel like talking about afterward. That day and night and the next day was the beginning of one of the times. Every time the door would open or shut, or anybody would forgit and squeak out loud in the kitchen, you'd hear Purty

fer-nice holler: "Oh, Joh-on!—and say, it got so I'd jump like a bronk at a rattler every time I heard her. And there was other things that got on a feller's nerves. She was purty sick, all right. And she wanted Johnny—and she ought to a-had Johnny right there with her—and Johnny . . . Johnny, he never come till we brung him in feet first, froze stiff as a log.

You've heard time enough about him starting home and gitting caught in the blizzard on that bare ridge they call the Devil's Backbone. It sure is bleak, up along that ridge....

Well, the baby didn't live more'n an hour or so, Allie said. Poor little devil, maybe it. met up with its dad some-wheres out on the long trail. I figured it that they both went about the same time, and maybe Johnny he located that pore little mite of a ghost and kinda cuddled it along.... You can't tell.

It was sure hard on Purty-fer-nice. I know there was one spell when she a kep' a-calling "Oh, Joh-on! till, honest, I used to set with both hands over my ears, even when I was in the bunk house and only imagined I heard her. That was hell all around.

She was so sick nobody dast tell her about Johnny till a week, maybe, after we buried him. And she kept a-calling him when she'.d hear anybody come into the house.... Say, I dream about that yet, when I've et pie for supper or anything like that. I don't hardly ever touch pie no more, just on that account; I'm liable to hear Purty-fer-nice holler "Oh, Joh-on!" and dream that Johnny's laying froze solid in the bunk house, where we brought him.... Yuh know I found him partly buried in snow alongside the trail, when the storm had let up and I was coming back from gitting the doctor. I found out in town he'd started home an hour or so ahead of the blizzard, and so I was looking fer him all the way back.

I guess it was a month or six weeks after that, when us fellers first found out that the old Lovelock was purty much to the bad all around. A red-faced, mouthy son of a gun from town drove out one warm day; and Allie told me he had Purty-fer-nice going south inside half an hour. Yuh see, Johnny had made his will right after he got married, and left everything to Purty-fer-nice to do-with as she seen fit. She'd had a lawyer out to the ranch and fixed up the red tape, soon as she was able to set up; Purty-fer-nice was great on being businesslike—I suppose that was the schoolmarm sticking out.

Well, anyway, we was taking it fer granted the outfit would go along purty much the same—only it wouldn't ever seem the same with Johnny gone—and all us fellers was wondering would we git canned or not, and saying we didn't give a cuss if we did, and that we was liable to roll our beds and hit the trail, anyway, if Purty-fer-nice tried to run things herself. We'd seen how she'd run Johnny—run him into his coffin at that; we all blamed her, kinda. fer what had happened—and we didn't want none of that in ours.

So then here comes this fish-eyed mark from town, with a mortgage in his inside pocket that Johnny had give him on a gambling debt, and a note or two, and asked Purty-fer-nice what she was going to do about it? Allie told me about it; she heard 'em talking and put me wise. This tinhorn offered to buy the ranch and cattle; he said he had outside capital to invest, and he'd take out what Johnny owed him—and that, according to him, was somewheres around ten thousand. Purty-fer-nice jumped at the chance, Allie said. She was sick of Idaho, anyway, and wanted to git back to what she called civilization. Also she didn't have no use fer the ranch on general principles, and she was sore because Johnny had gambled away all that money—which I've got my

doubts about, and always have had. I think there was some crooked work about them notes and that mortgage, and I thought so then. Johnny might drop a hundred or so, but he wasn't no high roller like them notes looked like.

Well, Purty-fer-nice she sent for me, and wanted to know how many cattle there was. They was dickering on the price then, and she'd agreed to sell out everything. I told her the tally books would show that, and went on to say that when a cow outfit sold out they most generally sold the books. You know—sold what the tally books showed.

Dickinson—that was the gazabo's name—he balked at that. He said he wasn't in the habit of buying sight-unseen like that. He'd pay fer what cattle was actually running the range, and not for what any book said ought to be. It had been a hard winter, he said, and the chances was a lot of stock had died off; in fact, he said he had heard on good authority that the range stock had suffered alf through the country. And he said he wouldn't buy no books. The cattle, he said, would have to be rounded up and counted, and he'd pay fer what there actually was.

A-course, there wasn't nothing fer me to say. I knowed he was a sharper and wanted the big end of the deal; and I knowed Purty-fer-nice wasn't able to hold her own with him; and I didn't have nothing but my own opinions, and what I knew of Johnny, to prove he lied and never had no honest debt aginst the Lovelock fer any ten thousand. All .I could do was keep my face shut.

Later on I heard what he was going to pay a head fer the stock, and it made me so sick I did go to Purty-fer-nice, and told her she was being hornswog-gled all around. And she give me to understand that I was to mind my own business, and not butt in. She said she was satisfied with the price, and had agreed to it, and had signed some kinda darned paper that clinched the deal. AH I was to do, she told me, was to gether up the stock and see that they was counted.

I wiH say she didn't come down on me with both feet, like she- done the first time I saw her, but she was purty cool—and if she hadn't been so little and peaked and white and kinda helpless looking, and if I hadn't heard her calling and calling fer Johnny when Johnny was laying dead in the bunk house, I'd 'a' told her to go to thunder, and gether up her own cattle.

She stood to lose ten dollars a head on the stock, and that counts up fast. She'd oughta asked me or some one that knowed, before she went and agreed on any price. And she'd oughta made 'em buy the books. And she'd oughta took some steps to find out fer sure whether Johnny owed that there Dickinson any" ten thousand dollars. But no—you can't beat a woman fer bull-headedness, especially when she's tackling something she don't know anything about. She wouldn't hear to nothing. I was to take out the wagons and gether the stock and bring 'em all in to the ranch; and I was to see that Mr. Dickinson had a chance to count the herd. And I was to keep my nose out of everything but my own affairs; she didn't say that, but she looked it and acted it. '

I tried to tell her that she better hold off till after the calf crop—but she got red and shut me off; she was one of them kind that mustn't hear nothing about one of the biggest things in life, because it's coarse! Couldn't tell her that, seeing Dickinson was buying the herd at so much a head big and little, every calf helped out that much.

"I prefer not to discuss such subjects," she says, and I had to quit right there. She said Mr. Dickinson was in a hurry—which I believed, all right; the quicker he could rush things through the safer he was in doing it. And she

said she was in a hurry, too. She would give immediate possession, she said, just as soon as the stock was counted and turned over. And I was to git right out and round up them cattle as quick as the Lord'd let me.

The storm that took Johnny and Johnny's baby had also put a crimp in the stock, all right enough. And they'd drifted. I got a full crew, and we combed the range from the Rockies to Salmon River and south to the Snake. We wore out the saddle bunch till there wasn't a day passed that some of the boys didn't come in off circle afoot and swearing to beat a full house. And while I'd dodged naming any figures when I was called on to hand out information to Dickinson and Purty-fer-nice, I knew within a hundred head how much stock we oughta have. I'd handled the Lovelock iron too long not to know; why, I coulda told 'em offhand how many calves had been branded for the last five or six years, and how many carloads had been shipped, and all about it. The last year, a-course, had kinda got past me, on account of Johnny running on the rope somewhat, and the hard winter gitting in its work. But making allowance fer poor cows and old stuff and yearlings we'd missed at weaning time dying off during that big storm and before that, there'd oughta been somewheres between four and five thousand head, counting the calf crop.

Well, the calf crop was short, a-course. And cattle must have drifted plumb outa the country. But the sick-enest part was the Lovelock critters laying in the little draws and brushy bottoms, or up on the bleak places where the big storm had caught 'em. All told, we drove just exactly nineteen hundred and seven head in to the big field over there east of the ranch. I had reps out with different outfits, a-course, but the word I got from 'em just before I hit the ranch wasn't much encouragement.

So there was the stock trimmed down more'n half, and there was Purty-fer-nice gitting bilked about ten dollars a head on what there was, and there was Dickinson with that ten-thousand-dollar claim aginst the estate which nobody asked him to prove or nothing, and which I didn't believe in atall. Honest, it was the rawest deal I'd ever went up aginst, and I guess I wouldn't 'a' felt much sorer about it if it was me gitting trimmed in a crooked game, instead of Purty-fer-nice. I didn't have no use for her, mind; I blamed heifer a lot of the trouble, and for Johnny passing out. But I do love a square deal—and I don't care who's setting in the game.

Well, I throwed the stock into the big field and rode up to the house and told Purty-fer-nice she could send word to Dickinson that the stock was ready to be counted. And then I went to the bunk house and flopped myself on a bed, and done some of the hardest thinking I ever done in my life. Letting Dickinson git away with it sure got my goat, as the saying is now.

A-course, it wasn't my funeral—and yet it was, too, kinda. Johnny had always counted on me to look out for things when he was gone, and take care of what belonged to him same as if it was mine. And I knowed how quick he'd 'a' made a roar about the way-things was going, if he'd been where he could do anything. And Johnny wasn't there, and so I kinda felt it was up to me to see that Purty-fer-nice had a fair deal. And it was the helenall of a job to look after her interests when she'd gone and balled things up with her darned agreements and her general bull-headedness. I couldn't even tell her she was gitting stung, and shoulda held out for selling the books and letting the Dickinson bunch do the gathering and counting. That's what I'd 'a' done. She coulda made a discount fer possible loss on the range, and still been

away ahead of what she was with 'em all gethered up and counted.

Well—I dunno as I oughta tell the straight of this. I dunno how it will look to yuh. But it sure looked good to me at the time, and it always has looked good. And I ain't never been troubled in my conscience fer what I done. So here's my hand, spread on the table:

I went and hunted up one or two of the boys, and talked the thing over with 'em, and then we got a couple more and chinned a while, and then we was ready fer what might befall—as the church hymn says.

Dickinson, he come out in a top buggy, and he had the cashier of a bank in the rig with him, and another feller lie called an expert accountant. He come down to where I,was, and said I could pick a man from the ranch—or two men if I liked, to count fer Purty-fer-nice. He said he wanted everything to be all straight and satisfactory, and that he would not fer the world cheat a woman. I just listened and said unh-iumh, like I swallowed it all as if it was oyster soup at a sociable, and went off and got my outfit together, and we all went down in the big field.

Sa-ay, have yuh ever been down east of the Lovelock, in that big field? It's just about two sections, you know, under bob wire fence. And yuh known that string of little buttes along about in the middle, don't yuh ? Four of 'em, kinda like a string of sausages—you know 'em. You can see 'em fine from the top of "the Devil's Backbone. Well, if you've ever been down close, you know how the one on the south end lays due north and south. It's little, and there's a narrow gully—oh, maybe two rod across in the widest place, and narrowing down on the east side to about twelve or fifteen feet—between that and the second butte; and then the other two swings back east, so they lay kinda cattacornering to the others.

Well. I put Dickinson and his two counters on gentle horses and led 'em down there, and showed 'em. the gulch and the herd grazing off to one side, all scattered out in rough country. I told 'em to git off and stand on one side of the gulch, and I'd put two men on the other side, and we'd drive the bunch through, single file.

Dickinson, he casts his eye out over what he could see of the herd, and then he turns to me, and says: "Oh—ah—about how many head do you think there is?''

I squinted out over the field and went through the motions of considering the matter, and then I said: "WTell, I never made no count. It's hard to say. They oughta be somewheres in the neighborhood of five thousand," I said. "The tally books showed that much last summer, and while there was some loss, a-course, there's the calf crop this spring," I told him.

He kinda grunted. "I ain't buying them by the book," he says purty short. "I'm buying what goes through this pass. Go start 'em up."

I rode off, kinda grinning to myself, and got the boys started. The. stock wasn't so scattered out as they looked from the buttes.

Y'see, I'd had 'em placed, like you place the furniture on a stage, to show up good from the front. And while the west side of the slopes was sprinkled thick with cattle," believe me, there wasn't none hid outa sight in the hollers! So I had the boys posted, and they worked 'em along toward the south end of the field to git around a deep gully—and for other reasons—and trailed 'em up to the pass, strung -out thin so'st they wouldn't bunch up and begin to mill; and an old bell cow from the ranch in the lead. Nineteen hundred head a cattle looks big to a greenhorn.

I rode up with a coupla the boys, and asked Dickinson if he'd ever counted cattle. He just the same as asked me

what it was to me, so I never said any more. The boys got their pocket of pebbles for counters, and I went back and got the old bell cow headed for the gulch and the rest follering along all right, and waited till they was stringing through the pass in good shape. And then I rode around with some of the boys to the other end of the gully to receive 'em as they come through, and send 'em on.

We-ell, we received 'em, all right; and things was going like clockwork. If they hadn't of went that way, I wouldn't be telling yuh about it. But I come purty near falling down on the job just because it did go so danged smooth. I hung around with the receiving crew till something kinda prodded me up that I better see how they was making out on the other side, so I loped around to where they was feeding cattle to them three town fellers steady as wheat into a mill. One of my boys I had counting for the outfit—Smiley, we called him—seen me ride up and flagged me. So I rode up to where he was counting opposite Dickinson and dropping a pebble in one of his pockets for every hundred—you know how they count stock.

We-ell, he didn't say nothing, but went on counting. But he give me a' funny look, and then tilted his head toward the thin little trickle uh cattle that flowed between us and Dickinson's bunch. The dust was purty thick by that time, and Dickinson was too busy counting to look our way, so I got off my horse and went up close to Smiley, like as if I was watching the cattle.

Smiley, he counted fer a minute longer, and then he says to me kinda worried and under his breath; but never taking his eyes off the cattle: "Rustle me another hatful uh rocks, Frank—and for criminy sake, don't send that old speckled cow with the twisted horn past us agin! She's gitting purty derned 'conspicuous. I've counted her four times a-ready, and I seen one uh them gazabos acrost there take a second look at her last time she went along."

I stood a minute longer, and went back and fell onto m'horse and rode down till I was outa sight, and then went hell poppin' around that little end butte, and stopped the percession. Sure enough, right turnin' the corner, as yuh might say, was the speckled cow with the twisted horn. I cut the bunch in two right there, and hazed her back north. I hated like sin to spoil that lovely ring-around-a-rosy, but it was better to be safe than sorry. I've always believed, though, I coulda made them town sharps count up another five thousand on theirselves, easy, before they'd commence to wonder how about it!

Oh, sure, they was satisfied, but kinda sour. They'd counted up a little over six thousand—and I couldn't help but think of that old yarn about the fish and the loaves uh bread, and about the widder's oil supply; I forgit what they called it. Dickinson he come to me, and he says, kinda grouchy: "That's more'n the record Lovelock had, isn't it? You said between four and five thousand. We've counted six thousand and thirteen—and your men have made it six thousand and nineteen."

"We-ell," I says to him, "we'll let your count go. I guess that'll be all right. And," I says, sober as you please, "you shoulda took my advice and bought the books. I know," I said, "about how these things come out. There's most generally less stock on the books than there is on the range; us cattlemen," I told him, "is inclined to be kinda careless after we git more stock on our hands than we can call by name."

"You certainly must be," he snaps out. "I'm paying for at least a thousand head more than the books have any record of."

"Well," I says, real cheerful,

"a-course you'd hate like sin to git the best of a lady to the extent of a thousand head uh cattle. And if yuh want to you can keep still about what stock the reps bring in later. That'll be none uh my business," I said. "I never did like Johnny's wife, nohow. I'll gamble," I told him, "she won't never know the difference; and," I says, "as long as she gits paid fer more'n what the books show, she's got no kick coming."

Well, that qUI skunk, he went down into his pocket and fished up a twenty-dollar gold piece, and give me! Sure, I took it. I got it now; and when I kinda git to thinking about old times, I try to figure out sometimes whether that there gold piece can rightly be looked on as a medal, earned by perfecting widders and orphans, or just a plain old piece of graft I oughta be ashamed of, but ain't.

Oh, sure, we throwed that herd right onto the range, and scattered 'em as quick as we'd branded the calves, and another hard winter or two come along; so Dickinson, he never did git wise. And Purty-fer-nice, she's back East—went quick as she got her money outa Dickinson's bunch—and I guess she's still telling it scary about us low brutes of cow-punchers out West, that ain't got no manners atall, and eats with our knives.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.