RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

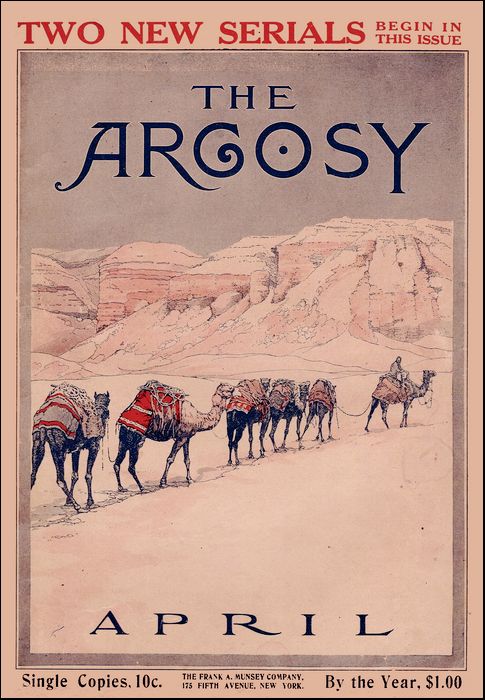

The Argosy, April 1909, with "Caruso on the Wire"

How a sleepy village came to be waked up, and the

indig-

nation of the magnate who was credited with the feat.

THE leading citizens of Vanceport were gathered in Isaiah Bender's general store.

It was a tempestuous night without, the rain slanting down in sheets and a stiff "nor'easter" whipping the bay into whitecaps; but not a man of the familiar coterie was absent.

Each one, too, as he stumped in to inquire for his mail, and then drift to his accustomed perch on a cracker-barrel or one of the back-tilted chairs about the stove, bore himself with a certain accentuated and impressive dignity; for this was late in the fall, and such a "spell o' weather" plainly betokened the departure of the most belated and persistent summer visitor—those eagerly welcomed but none the less despised invaders who usurped the life of the little village from June to October of each year.

In other words, the leading citizens of Vanceport felt themselves restored to a position of authority, able once more to play the oracle without having some "Smart Aleck from the city" cut in to challenge their dogmatic utterances. With so intoxicating a sense of freedom from restraint, not one of them would have missed coming to the store that night had the storm been twice as bad.

Captain Asa Ketchum was the last to arrive.

"Whoopee!" he boomed exultantly, as he sent a spatter of raindrops about him with a wave of his sou'wester. "Haow's this fer dirty weather, mates? Black outside ez the inside of a black cat.

"Them 'lectric lights o' your'n, Isaiah," with a quizzical glance at the storekeeper, "don't seem to be workin' none too well to-night."

An appreciative "Haw-haw!" from the circle greeted this sally; for Bender had been advocating such an improvement in the village for the past five years, but with scant encouragement.

It was not that the Vanceporters did not realize the advantages of a better illumination; they balked at the increase of taxes it involved.

Uncle Billy Gale expressed something of the general sentiment now, when, after the laugh at Isaiah's expense had subsided, he remarked, glancing pensively toward the darkness outside:

"Ef we had many sech nights ez this, I'd almost be ready ter come to 'Saiah's way o' thinkin' myself, ef it didn't cost so all-fired much."

"Yes, that's the way with all o' yew," jeered Bender, rallying finely. "Yew're the sort that sez: 'Ef we only had some ham, we'd have some ham an' eggs—ef we only had some eggs;'

"Naow, look at the propersition," launching forth upon his favorite hobby. "The hull thing can be put in fer three thousand dollars — power-house, poles, wires, dannymo, an' all; an', figgerin' on the lowest basis, it's bound ter pay fer itself, together with cost o' maintenance, intrust on investment, repairs, incidentals, an' et cet'ry inside o' ten years, which means—"

"Hoi' on, hoi' on thar, 'Saiah!" interrupted Captain Asa, repentant of the pleasantry which had stirred up this ebullition. "That may all be. I ain't a disputin' yer figgers none; but yew 'pear ter fergit we're all gittin' on in years. We mayn't none of us be here by the time that thar lightin'-plant is paid fer; an' in the meanwhiles look at the burden we'd have to carry. Taxes is sure high enough ez it is."

He glanced about him with the triumphant air of one who has evolved an unanswerable argument, and was rewarded with slow nods of approval from most of the circle.

"It's all on account of that air pesky tariff," piped up Seth Gentry, a dyed-in-the-wool Democrat, who never could resist an opportunity to switch the conversation into politics. "Ef 'twa'n't fer that a' eternally takin' toll on every scrap o' clo'es a body wears, an' every bite o' vittles he puts inter his mouth, mebbe we could see our way cl'ar ter—"

"Shucks!" disclaimed Eph Fanshaw, an equally uncompromising Republican. "Yew ole fool, cain't you reelize that pertection to 'Merican industries is all that keeps this country a goin'? We'd be like the downtrodden masses o' Europe ef—"

But Bender put a stop to the discussion by banging, his fist down on the counter and declaring that unless the disputants ceased he would close up.

"'Lection's over," he grumbled, "an' yew don't s'pose I'm goin' ter stay up an' burn ker'sene ter hear that sort o' guff. What we was a talkin' about was the lightin' question, somep'n that vitally interests every man, woman, an' child.

"Naow," he went on, assuming an oratorical pose, "Cap'n Asa here has advanced a objection which seems ter have some meat in it. He says ten year' is a long time, an' we might all be in our graves 'fore the plant is paid fer, an' we're free of the burden."

"Well, ain't it so?" demanded Captain Ketchum sharply. "Didn't yew say yerself that it'd be ten year' afore the debt was cl'ared off? "

"Yes," assented Mr. Bender, "I did; but that, ez I told yer, was figgerin' on the lowest possible basis; whereas, thar's skursely any doubt but what the plant would make three, four, or five times the amount I say.

"By gorry," he concluded enthusiastically, "ef we do what's right an' stick the summer people double what we do the home folks, thar ain't no reason why we can't make the thing pay fer itself in one year."

"If it's as good as all that, why don't you put the scheme through yourself, Mr. Bender? I heard you tell a traveling man only yesterday that you could sell out the business here any time you wanted to for five thousand dollars."

The voice which propounded this query came from without the charmed circle, and had not hitherto been heard. A different voice it was, too, from the lazy drawl of the leading citizens—quick, alert, inquisitive.

Its owner matched with it, a youth of twenty or thereabouts, grown so fast that the legs of his patched trousers did not reach to his shoe-tops and the wristlets of his calico shirt were half-way up to his elbows. Rather a grotesque figure, reminding one of a half-reared setter-pup with his shock of red hair, and his hands and feet too big for his lanky limbs; yet, as with the setter-pup, his face wore a look of keen intelligence, which promised a shrewd and capable maturity.

Vanceport, however, held him in slight esteem. He was entirely too knowing, according to their ideas—too given to asking inconvenient questions, such as that which he had just put to Bender.

The circle turned as one man to regard him with stern rebuke; and the storekeeper, a trifle flushed, snapped tartly:

"S'pos'n yew keep yer lip out'n things what don't consarn yew, Ike Somers, an' at the same time yer fingers out'n my cracker-bar'l."

He crossed over to slam down the lid, beneath which the other's hand had been exploring.

"But why doesn't the electric-light question concern me?" persisted the offender, unabashed. "Ain't I a property owner just the same as any of the rest of you?"

"Oh, I know," with sudden passion, as a titter ran through the group, "you call it a patch of scrub-oak back on the rise, and think that it's worthless.

"Of course, it's worthless now, and always will be so long as a lot of old stick-in-the-muds like you run this village. But show a sign or two of life here, put in some modern conveniences like this electric light to attract people to the place, and you'd soon find home sites, no matter where located, commanding a good price.

"Concerned?" he finished hotly. "Seems to me, I'm more concerned than any of the rest of you."

The others sat silent for a moment, frowning at the effrontery which dared to arraign them, but unable, to find a suitably crushing reply.

They could not gainsay the young fellow's argument, for they had seen neighboring villages bloom and blossom into prosperity under the adoption of similar improvements; but they were unwilling to grant the logic of such a "shallow-pate."

Even Bender repudiated Ike as an ally, and somewhat hastily brought forth a revelation which he had intended to reserve as a surprise.

"Ahem," quoth the storekeeper, clearing his throat. "Whether the 'lectric light would increase the vally of some of the old medder an' scrub-oak land around here is, I guess, gents, a doubtful question. What we was a discussin' was whether it would conduce enough to the gin'ral comfort an' well-bein' of the village for us to afford it.

"Cap'n Asa, here, says no. He says taxes is high enough as they is; an' I guess nobody in the main ain't a disagreein' with him."

A mutter of unanimous assent rose from the tight-fisted company.

"But," resumed Isaiah, "what ef we could get the light without a penny's wuth o' cost to us, or a single dollar added to the burdens of this here community?"

They gaped up at him incredulously, the slow thought coming to some of them that possibly his overweening interest in the scheme had turned his brain.

"Oh, yew needn't look so s'prised," he chuckled,"I've got a plan, all right, an' a plum good one it is, tew. Who'd git the most benefit out'n 'lectric lights, let me as't yer? Who is it 't allus does the most kickin' on our dark streets, an' on havin' ter use ker'sene lamps in their houses? Yew all know without me a havin' to tell yer.

"Well," he went on, "I was a settin' stewin' some o' them things over in my mind the other day, when all of a sudden it come to me jest like a inspiration: Why not make the summer people foot the bill?"

"Inspiration?" excitedly broke in Ike Somers, who had been following the narration with gradually widening eyes. "Why, I asked you that question myself after I heard you tell the drummer that you'd given over all hope of ever getting these old tightwads here to take up with the proposition."

Bender turned angrily at the interruption. It was all he could do to restrain himself from flinging a scale-weight.

"Shut up, thar," he snarled, "or, by gum, out that door yew go, an' yew don't never come in ag'in neither. Yew're wuss 'n a pesky 'skeeter, buzzin' 'round with what yew said an' what yew done. Whoever'd pay any 'tention to what yew say, I'd like ter know?"

He would probably have continued on in the same strain at length; but at that moment there came a shrill hail from outside, and the Bellville stage splashed by without stopping.

Isaiah hastened to the door, and came back with a limp mail-sack which the driver had flung upon his steps.

"Don't gin'rally disterbute this bunch till mornin'," he observed, opening the bag and drawing out the handful of letters it contained, "but seein' 's were all here, an' thar might be some answers from the city folks to the epistles I wrote 'em on the stren'th o' that there inspiration of mine, guess 't won't do no harm ter take a peep naow.

"Yes, by gosh," he ejaculated a second later. "Five on 'em. All what I wrote to. An' nothin' else," tossing the empty bag into a corner, "'cept'n a rheumatism circular fer Ezra Durkee, an' a picter post-card fer 'Nervy Davis from her beau. Wait till I see whether he says he'll be down next Sunday."

His curiosity relieved upon this point, he returned to the stove and the eagerly waiting company.

"M-m-m," he mumbled, as he opened and ran through one after another of the letters. "Dr. Butts says no. Well, I didn't expect nothin' much from him. Nor from Eversley Perkins, neither, who likewise 'begs to decline.'

"Gee, here's^ a reg'lar book from Mis' Harriott—four pages of it—but I see she ends up with 'regretfully yours,' so I guess thar ain't no use wadin' through the rest of it. "Colonel Carson don't bite, nuther. Wal, naow, that's some kind of a surprise to me. I counted sorter confident on him comin' in with a fair conterbution.

"But, here," and he held up the last letter, "here is one I'm willin' to bet on 'fore I open it. 'Twenty-Third Street National Bank, Ramsay Grant, president.' Purty near smells of money, don't it? An' him the so-called king of the Vanceport summer colony. Yew kin all go bail he's come down handsome."

While the others waited with bated breath, Bender -opened the letter and glanced through it; then sank back in his chair with a gasp, the typewritten sheet fluttering from his nerveless fingers to the floor.

Ike Somers picked it up and read it aloud:

"Dear Sir:

"In reply to yours of the 15th instant, I beg to state most emphatically that I will not do for you, or assist in doing what you should long ago have done for yourselves. In fact, I have become so disgusted with the antiquated and dilatory methods in vogue in Vanceport, that I have about made up my mind to abandon my summer residence there and remove to some other place of more enlightened standards.

"It will do no good to communicate further with me on this subject, or attempt to change my decision, as my, purpose is unalterably fixed. Anyway, I leave for Europe to-morrow to be gone until late next spring.

"Very truly yours,

"Ramsay Grant."

The reader's voice was trembling as he came to the end of the letter, and when he had finished he paused a second, then turned upon his audience with an explosion of wrath.

"Now see what you old mossbanks have done with your penny-wise-and-pound-foolish policies," he raged. "You've driven Ramsay Grant out, and every one knows that if he leaves all the others will follow suit. In two years from now Vanceport will be too dead to skin. Oh, you clams, you lobsters, you short-sighted idiots, you—!"

But this was too much for Bender to stand. Overwhelmed though he was by the downfall of his cherished hopes, and appalled at the bank president's threat of removal, he yet could not permit himself and his friends to be thus assailed by the village pariah.

With outraged dignity, he sprang to his feet.

"Ike Somers," he roared, "yew git out o' my store, and don't yew never das't so much as poke yer nose inside ag'in. I've said it afore, but this time I mean it. Noaw, git!"

And thus driven forth, Ike Somers missed the subsequent event, which turned the gloomy assemblage into one of rejoicing and festivity.

Instead, sore and desperate, seeing nothing ahead for him but penury and hardship, he plunged forth into forbidden paths.

IKE SOMERS'S home was on the outer edge of the village, about a mile away from Isaiah Bender's store.

His father, an invalid student, advised by his physicians to seek country air, had been inveigled by a rascally land-shark into paying an exorbitant price for twenty or thirty acres of scrub-oak and sand. He died soon thereafter, and this property had been left as the sole patrimony for his widow and only son, a lad then of only ten years.

They had held onto it. Indeed, they could do nothing else; for no one would buy it, and they had nowhere else to go.

How the two managed to live, Providence alone knows. The place produced little or nothing, and work which either of them were capable of doing was scarce in Vanceport. Yet, somehow they managed to eke out a precarious existence, keep a roof over their heads, and scrape up annually the few dollars required for taxes on their land.

Moreover, the hard-worked, busy mother found time to carry on the education of her boy, the foundations of which had been laid by the student father; and Ike, naturally bright and precocious, was as far advanced for his years as many a lad with much better advantages.

He had an ambition to make something of himself, and almost from the time he had discarded pinafores had declared that some day he would be a lawyer; but he began to realize now that such an aim could not be attained without going through college and law-school, and this seemed impossible.

Had he been foot-loose, he would have tackled the proposition as many another young man has done, and worked his way through the institutions; but he felt that at present he could not leave his mother.

Her health was markedly failing under the long strain she had borne, and he was being more and more called upon every day to assume the burden of their joint maintenance.

True, it was but little he could earn at the odd jobs which came his way—opportunities for employment were scarce in Vancegort, and his sharp tongue and superior attainments rendered him anything but popular in the village. Yet he also knew that if it were not for what he was able to contribute, their meager larder would often have been entirely bare.

The one hope on which he fed his soul was that, by some rejuvenation of the sleepy community, their land back on the "rise" might be sold for enough to support his mother while he was preparing for his profession; and with this idea in mind, he had been ardently interested in Bender's efforts to secure electric lights.

With city conveniences to back up the natural advantages, and beauty, of the locality, he reasoned that a largely increased number of summer visitors would be attracted to the place; and he was shrewd enough to see that his despised "patch of scrub-oak," being just beyond Ramsay Grant's villa, would then become the most available site for bungalows and cottages.

And now all his fond dreams were knocked on the head; for, with the final and decisive refusal of the city people to take up the project, it was hopeless. The Vanceporters themselves, he well knew, could be trusted to maintain a masterly inactivity.

Then, to cap the climax, he had, by his own impulsive outbreak at the store, worked himself out of the sole source of income, little as it was, upon which he had been banking for the coming winter.

In return for such assistance as he could render about the place, Isaiah Bender had allowed him to maintain a picture post-card stand on the premises; but Ike had noticed that the proprietor was daily regarding the scant profits of the innovation with a more and more covetous eye, merely seeking an excuse to take it over himself; and hence he had no doubt that the dismissal of that evening would stand.

What he could do now to provide the necessaries of life for himself and mother the young man was at a loss to decide.

Turning over these problems in his mind, and with a deeper and deeper sinking at his heart, Ike plodded sullenly homeward through the mud and rain along the dark country road.

He was sore at the world in general, sore at Isaiah Bender and the circle of "leading citizens," but especially resentful against Ramsay Grant, upon whom he had pinned his highest hopes, and whose letter he blamed more or less unjustly for his present misfortunes.

He stopped now, while passing the banker's dark house, showing dimly back among the trees, to shake a vengeful fist toward it.

"Why couldn't he have given the money?" he muttered bitterly. "He'd pay three thousand dollars for an automobile for his own pleasure, and think nothing of it. Yet, when it comes to something which would benefit other people, he closes up tighter than an oyster. By George! if they called me the 'king' of a place, I'd try to do something to deserve the title."

The sound of a loose shutter banging to and fro in the wind against the unoccupied house attracted his attention.

"That's the one on the pantry window that I fixed for him last winter," he commented;" and small thanks I ever got for it. It can bang itself off, for all I'll ever touch it again. Serve him no more than right if a tramp should come along and carry off everything he's got inside."

"He drew his ragged hat-brim down over his eyes and. trudged on a few steps farther up the road, but the persistent clang of the shutter rang out after him like a call and once more brought him to a halt.

"There's a lot of valuable things Grant leaves there," he thought. "I'll bet a chap could scrape up a hundred dollars' worth in a small parcel and sell them in the city with no trouble at all. And a hundred dollars would carry mother and me over the winter in fine shape."

He caught himself sharply together as he realized whither his thoughts were leading him.

"No," he muttered between set teeth, "I'm no thief."

And thrusting his hands deep into his pockets, he again started off.

In order to divert his mind from temptation, he tried to dismiss Ramsay Grant from consideration and center his spleen on the sluggish Vanceporters; but he could not shut out the sound of the discordant shutter from his ears.

The wind was rising, and the reverberating clang followed him ever louder and more compulsory.

"I wish I could think up some plan to soak Bender and that gang of old lobsters," he communed with himself, striving to close his ears to the shutter's din. "If only—"

He stopped suddenly and turned about, either at the prompting of some new suggestion, or because the lure of easy entrance to the untenanted house had finally grown too strong for him.

Evidently, the latter, it appeared; for after a moment's wavering, he retraced his steps to Grant's place, and, leaping the fence, stole up through the shrubbery to the side of the house.

It was as he had anticipated. The shutter, upon the pantry window, working loose in the storm, had rendered access to the villa easy. All one had to do was to break a pane of glass, manipulate the catch upon the sash, raise it, and step inside. There was no need of caution. The road, out this way, was a lonely one at the best, and certainly, on such a night as this, no one would be abroad.

Nevertheless, Ike carefully muffled the stone which he had chosen for a burglar tool, and upon the faint jingle of the breaking glass, dodged hurriedly back into the bushes.

Satisfied at length, though, that his operations had been unheard, he emerged again, completed his work and, having secured the clattering shutter so that it would attract no one else to the scene, disappeared inside.

It was about an hour later that Ike, weary and wet, reached home. He did not seem pleased that his mother had waited up for him, and rather avoided her eye as he mumbled something about being tired and wanting to go straight to bed; but she called him to her side.

"What is the matter, my son?" she questioned. "There is something wrong, I know."

He tried to evade and put her off; but was finally forced to tell that the electric-light scheme was a "dead cock in the pit," and also to confess that his unruly tongue had lost him his position at Bender's.

She paled a little after she took in the full force of his disclosures, and was silent for a moment; then she spoke up resolutely:

"Well, that apparently settles it. There is nothing left for us here. We shall have to go to the city."

He gazed at her wjth slowly dilating eyes.

"Do you really mean it?" he burst out.

More than once he had urged this course upon his mother, and tried to convince her that in a wider field of activity they could do better; but hitherto she had always resisted, clinging with a woman's conservatism to the hope of ultimately selling their land, and thus providing revenue for his education.

She was afraid that if he should take up some other means of livelihood, and follow it for a year or two, he might become weaned away from his early choice of a profession; and she was even more ambitious than he to see him a lawyer.

Now it seemed, however, as though the option were taken from her hands. They were being literally driven out of the narrow little community which, with its different ideas and different standards, had never done more than tolerate them.

Mrs. Somers realized at last the force of the .old saying: "Who can pit himself against destiny?" and so resigned herself to the inevitable.

"Yes," she sighed, "I mean it, Ike; " and repeated, "there is nothing else to do."

"And when shall we go?" he demanded.

His eyes were shining now; his whole manner had changed.

"When? Oh, at once, I suppose. There is really no reason why we cannot leave to-morrow, except for tht doubtful chance of getting somebody to take this place off our hands for a few dollars."

"Oh, no," he urged, "don't let's wait for anything. We couldn't get ten cents for the old place if we waited a year, and we'd simply be eating up the little money we've managed to lay by."

"But remember how little that is, Ike," she cautioned. "It will be barely sufficient to take us to the city and pay our board there for a few days. Suppose you are unable to get work at once? What will we do then?"

His face clouded for a minute; then he slowly raised his head with a. dogged, obstinate expression.

"I'll chance it," he said curtly. "Don't you worry, mom. Even if I don't catch on right away you sha'n't suffer. I'll—I'll take care of you some way."

MEANWHILE the flow of comment and criticism at the village store was running at full tide.

Isaiah Bender, it is true, after rousing up to eject Ike, had sunk into a state of pessimistic depression and sat morosely silent; but the tongues of the others, as though the youth's departure had removed a clog, wagged more vigorously than ever.

All of them were secretly terrified at Ramsay Grant's threat of leaving, but, with a sort of bravado, they pretended to regard it in a philosophic light.

"Wal..."—Uncle Billy Gale paused to expectorate, and hit the small orifice in the door of the stove with the precision of a sharpshooters "Wal, mates, Vanceport was here afore Ramsay Grant ever come, an' I guess it'll stay here, whether he goes or stays."

"Aw, he ain't goin'," blustered Captain Asa. "It's my private opinion he's jest makin' a bluff ter try an' skeer us inter puttin' in the 'lectric light ourselves."

"Yes, that's the way with them pesky plutocrats," warmly assented Eph Fanshaw. "They're always a tryin' to make the poor folks grind their axes fer 'em. I wouldn't vote fer no electric light now, jest to spite him."

"No, nor me, nuther." Uncle Billy's quavering voice was raised again. "What good is 'lectric lights anyhow, 'cept'n as a excuse, an' temptation fer young folks to be out frolicadin' round at night when they ought ter be safe in their beds? Lanterns was all my father an' my gran'father had; an' what done fer them I guess 'll do fer me. 'Sides I doubt if t'other thing is Scriptooral."

Cap'n Asa caught at the point and embellished upon it.

"By heck, Uncle Billy, I don't know but what you're right. Look what their 'lectricity has done fer 'em up thar on Broadway in Noo York! How'd we like ter see our main street here turned inter a 'Great White Way,' with play-houses an' all kinds of dens of iniquity all along it? No, sir; I say let's write a letter hot an' heavy to Ramsay Grant, an' tell him that sooner 'n put up our gdbd money fer such deviltry we'd ruther have him go."

Isaiah Bender broke his moody silence with a bitter laugh.

"I didn't hear of no such scruples when you thought Grant might foot the bill," said he.

"But don't yew see," contended Captain Asa, "that was different. In that case, the sin would have been on his shoulders, not on our'n. I say, let's write him the letter, anyhow, jest to show him that we can't be skeered or bluffed; an' then if he chooses to go, let him go."

"An' at the same time yew might as well hang up the bankrupt sign oyer all Vanceport," Isaiah snapped, "'cause that's what it'll mean ef Grant does git out. Howsomever, thank Heaven yer letter won't have no chance of reachin' him, since he—plainly says he's leaving fer Europe ter-morrer; so that settles that.

"An', naow," rising to his feet, "git out, all o' ye, 'cause I'm goin' to close up. I've heerd about as strong a mess o' fool-talk as I can stand fer one evenin'."

They arose slowly to their feet at his behest and, struggling into their oilskins, started for the door; but at that moment the telephone bell rang, and they lingered with natural curiosity to see what it might portend.

"Fer the land's sake," grumbled Isaiah, circumnavigating the counter to reach the instrument, "who's callin' me up naow? I'll bet Almiry Cooper's Uncle Sol has driv' over from Bellville unexpected ag'in, an' she wants some bacon fer breakfast. Well, ef she thinks I'm goin' to pack it clear up to her house sech a night as this, she'll git' fooled. I'll be out of every livin' thing she wants."

By this time, though, he had taken down the receiver and was gruffly bellowing " Hallo!" into the mouthpiece; then, as though by a miracle, his tone suddenly became as suave and smooth as oil.

"Why, Mr. Grant!" he cooed. "This is a s'prise party. I didn't know you was in town at all. Yew, sure, didn't come on the stage to-night, did yer?

"What?" with lively "astonishment. "Yew ain't in Vanceport at all? Yew're in Noo York, a talkin' to me from the Metropolitan Op'ry House! An' yer voice as cl'ar as ef yew was standin' right at my very elbow. Wal, wal, now, ain't that wonderful?

"What's that yew say, Mr. Grant? Not to pay no 'tention ter that letter yew wrote me? 'Twas all a mistake of yer secketary?"

Isaiah had fairly to clutch at the instrument for support, and the listening group eagerly tiptoed, nearer, involuntarily bending their hands behind their ears as hoping to catch the cheering message coming over the wire.

"Yew're a tellin' me, then, that 'yew will stand fer the 'lectric-light proposition, an' pay all the cost yerself?" gasped Isaiah breathlessly. "Wal, naow, that is ceft'nly han'some, Mr. Grant. Vanceport'll sure remember yew in its prayers.

"Eh?" he interrupted himself. "What's that? C'ruso is jest erbout to sing; an' ef I listen, I kin hear him over the wire?

"Hi, fellers," and he turned excitedly to the others, "what d'yew think of that? He says he's goin' to stand away from the telephone, an' let me hear—"

He stopped suddenly, and over his fat, complacent face, with the short chin-beard, spread an expression of startled awe, of amazed delight.

"By glory, boys," he shouted, "it sounds like the gates of Heaven had been pried open, an' yew could hear the angels singin'! Here, Uncle Billy, jest listen to nim."

He thrust the receiver into the hands of the patriarch, who became almost equally enchanted, and gave way only reluctantly to the insistence of Captain Asa Ketchum that he, too, should hear.

And now arose a veritable free fight over the possession of the instrument. Every one wanted to try the novelty, and, having tried, was loath to step aside. Those who had heard once eagerly clamored for a second chance, and,the man in temporary control of the receiver was an active storm-center, with all the rest jostling and pushing and struggling to wrest away his prize.

The "diamond horseshoe" never contained a more appreciative audience than that little coterie gathered among the hams and calicoes of that country store, listening to Caruso as he sang a famous air from "Rigoletto."

Bender himself was at the phone when the end was reached—that brilliant cadenza which never fails to evoke a tumultuous round of applause.

He was standing with closed eyes drinking in the music; but as the full, trumpet-Jike tones trilled higher and higher, his lids widened, and he raised himself until he stood upon his toes.

Then he came back to earth with a thud, dropping the receiver with a crash, and staring about him in startled alarm.

A second later he was bellowing into the instrument at the top of his voice.

"Hey, what's the matter thar?" he shouted; then, after an interval, in less excited tones: "Oh, so that's yew ag'in, is it, Mr. Grant, an' what stopped the music was yew a shuttin' the door of the booth? By gee! when that feller went skimmin' up ter the clouds that way, an' then all of a suddin I couldn't hear nothin', I think sure he must have bu'sted his throat.

"Did we enjoy the music? Yes, sir, yew bet we did. Ask Uncle Billy Gale here, what ain't never been to a playhouse sence he seen 'Ten Nights in a Bar-room' down at the ole Bow'ry Theayter, in '62. He's a figgerin' naow on takin' the money from his turnips an' goin' inter town to hear the hull of that air piece.

"An' now, ter git down to business ag'in, eh? Yew say yew won't be able to git down here afore yew sail; but to go right ahead an' have the 'lectric-light plant put in, an' yew'll settle when you come back in the spring? Oh, yes, that'll be all right, Mr. Grant. Jest so that we know yew're goin' to foot the bill in the end.

"An'—What's that? Yew think this'd be a good time to put in some other improvements that is badly needed? Wal, I don't know, Mr. Grant. Yew see, taxes is pretty high now, an' our folks—

"Oh, yew're willin' to go inter yer own pocket fer the other things, tew? Wal, now, that is cert'nly squar' on yer part, Mr. Grant. It's more'n squar'; it's deownright ginerous.

"A town hall? With a stage an' scen'ry on it? Yes, indeed, sir; I cert'nly dew think it's badly needed. An' what'11 sech a buildin' as we require cost erbout? Wait a minute, sir, an' I'll ask Eph Fanshaw, here. He's a builder, an' he kin prob'ly give yew a rough estimate."

He slid his hand over the mouthpiece, and turned to question the man of practical knowledge.

"One that'll seat erbout tew hundred people, Eph," he explained. "An' finished pretty nifty both inside an' out."

Fanshaw calculated laboriously with a stubby pencil on the lid of a flour-barrel for a minute or two, and then announced that, in his opinion, "fifteen hundred'd come close to seein' things through"; but this did not at all satisfy Isaiah's expanding views.

"Shucks!" he growled. "Ramsay Grant'd think yew was plannin' ter build a dog-house."

He turned to the telephone again, and explained in dulcet tones that since they did not wish to "stick" their benefactor, they had concluded a town hall costing three thousand dollars would serve all their present needs.

"What'd I tell yew?" he observed a second later, as he again shut off the mouthpiece to turn a beaming glance upon his associates. "He made no more fuss over it 'n yew would in swallerin' mush an' milk fer breakfast. I'm only sorry now I didn't raise the figger to five thousand."

On the subsequent items, however, Isaiah gave himself no sueh cause for regret. Mr. Grant proposed a new Union Church, and was promptly held up for eight thousand on that score. A new schoolhouse was decided upon, which Bender told the donor he was getting cheap at four thousand.

The electric-light plant, which it will be remembered was originally estimated at three thousand dollars, it was now discovered could not be put up for a cent less than double that amount and a thousand dollars more.

Still, the bank president seemed in no wise dismayed at the rapidly mounting total, nor at all inclined to be critical of the figures suggested to him.

He assented to everything without demur or haggling, and immediately went ahead to discuss some new subject for outlay.

At last, when Isaiah's brain was fairly whirling, and the others had reached a state where they could only gaze at one another in dazed incredulity, he halted.

"I guess that is all," he remarked. "Or, no—I was forgetting about those execrable paths you have down there. Have a three-foot cement walk laid along the road leading to my house, will you, Bender, and have it extend about a quarter of a mile beyond my place."

'"Beyond your place?" Isaiah dissented. "What's the use o' that? Thar ain't nothin' more out in that direction 'ceptin' Mis' Somers's scrub-oak patch."

"And that is exactly the reason why I wish it done," retorted Grant. "Mrs. Somers is a worthy and estimable woman, and if I can be of assistance to her, I shall be only too glad of the opportunity. While I think of it, too, don't forget to see that one of the new electric lamps is hung opposite her property."

And with that he rang off.

The storekeeper's face was a little clouded as he turned from the phone.

"The idee," he grumbled, "of wastin' good cement a runnin' a walk out to the Somers place, an' hangin' a lamp out there to light the owls an' chipmunks! What he ought ter 'a' done was to put that walk in front of my store, an' give me a extry light on this corner in return fer all the trouble I'm takin' fer him."

His expression slowly cleared, though, as he recollected the full extent of the blessings which he had gained, until at last the little drop of bitter in the brimming cup was forgotten.

"Glory hallejuhah, boys!" he ejaculated, cutting a pigeon-wing in his exuberance. "Jest think of it! We're goin' ter git free, gratis, fer nothin' our 'lectric lights, an' a church an' a school-house, an' cement sidewalks, an' a taown hall!"

"A taown hall with a stage an' scen-'ry," amplified Uncle Billy Gale, with sparkling eyes. "Oh, I tell yer, fust thing yer know we'll have a Gre't White Way of our own, an' mebbe have C'ruso standin' on that stage an' scen'ry a sing-in' fer us!"

THAT was a busy winter in Vanceport. Day after day and week after week the carpenters and masons and bricklayers and plasterers and painters worked with unflagging industry. The ringing blows of the hammer and the blithe tap of the trowel came to be familiar sounds.

It was not long before the powerhouse, the church, the school-building, and the town hall began to assume visible form; and then Vanceport, as though awaking from its long doze, commenced to sit up and take notice.

There is no more powerful incentive than example; and when the villagers saw the pretty and substantial public structures which were going.up, they felt stirrings of shame at the weather-beaten and faded condition into which they had allowed their private properties to lapse.

Eph Fanshaw was one of the first to act upon this impulse by replacing his dingy old carpenter-shop with a commodious, modern building. True, the step was taken largely on account of the increased demands of "his business; still it must be confessed that a far less ornate structure would have satisfied all his requirements.

Nor could any such excuse be adduced for the attractive new front which Isaiah Bender added to his store, or for the transformation of Uncle Billy Gale's old blacksmith forge into an up-to-date machine-shop and garage.

-Indeed, the fever proved of a most "catching" variety, and even where there was no rebuilding or repairs, there was a general freshening up with paint and putty, and such a "readying up" of yards and gardens, that, as the Rev. Jonathan Short expressed it on one of his bimonthly Sunday visits, "Vanceport shone like a bride adorned for her marriage morning."

The town, too, began to boast an increase of population. With the demand for labor, artizans and mechanics commenced to move in, and to erect homes and cottages for their families.

A village improvement society was finally formed, and a hot discussion opened up in favor of a trolley line to Bellville to take the place of the antiquated stage.

Yet, despite all the expense of these various repairs and additions, nobody seemed to be out of pocket. Indeed, money had never been so plentiful in the village; and Isaiah Bender found to his surprise, on footing up his hooks, that his winter's business, even after deducting the cost of the alterations to his store, was more than treble the best summer trade he had ever known.

It was about this time, too, that Ike Somers, at his new home in the city, began to receive letters offering him gradually enlarging amounts for his "patch of scrub-oak."

The first was from Isaiah Bender, and made a tender of five hundred dollars, which Mrs. Somers was inclined to jump at; for, although Ike had secured a position as a newspaper reporter, his earnings were still meager and the starting of his law studies still loomed dim and far away.

Ike, however, advised her not to be too anxious, but to hold off a bit; and the wisdom of his course was shown a week or two later, when a missive arrived from Uncle Billy Gale, raising the bid to six hundred dollars.

After this, letters from the "leading citizens" appeared at frequent intervals, and the price of the land steadily advanced until it had reached five thousand dollars.

Then Ike cut short the avalanche of correspondence by informing the crew that he would take no steps in the matter until he had run down to Vanceport and looked over the ground himself.

"There is undoubtedly a good-sized 'culluhd pusson' in this woodpile," he said to his mother, "and I am certainly not going to close until I find out just what and where he is."

Moreover, when he finally did revisit his old stamping-ground, it was in a professional capacity.

Much to his surprise, his city editor called him up one morning and directed him to take an assignment at Vanceport.

"To Vanceport?" Ike exclaimed amazedly, for he had been so out of touch with the old place that he had no knowledge of the remarkable changes which had occurred there.

Nor, it may be observed, had any mention of them been vouchsafed in the epistles of the "leading citizens."

"To Vanceport?" he repeated. "What on earth is going on. at Vanceport that merits the attention of a metropolitan daily?"

"Oh, they are going to have quite a celebration down there, I believe. Opening of a lot of new buildings, inauguration of an electric-light plant, and all that sort of thing. Kind of a 'harvest home' lay-out, don't you know?"

But Ike seemed not to be listening.

"Opening of a lot of new buildings!" he gasped dazedly. "Inauguration of an electric-light plant! At Vanceport, did you say?".

"Yes. Ramsay Grant, the banker, who got back from Europe yesterday, did it all for them; and this is to be a sort of 'welcome-home' and grand pow-wow in his honor."

The reporter's face was more than ever a study.

"Ramsay Grant?" he ejaculated unbelievingly.

Then a great light fell upon him.

"Oh, say, chief, I can't go to that," he stammered hurriedly. "Send one of the older men. I couldn't handle an affair of that sort. I—I'm sick."

But the other would listen to no excuses. There was no one else who could be spared for the assignment, it appeared, and, protest as he might, Somers in the end had to go.

Still, it must be confessed that for a time after his arrival he kept himself pretty sedulously in the background.

He dodged about back ways and through unfrequented thoroughfares in order to get his notes and snapshots of the new buildings and changed conditions, and it was not until he had strolled out along the new cement walk leading to his former home that he dropped the attitude of a skulking fugitive.

Altered as the rest of the village had appeared to him, he had to rub his eyes before he could make himself believe that this was the same locality he had once known so well.

Houses, either finished or in course of construction, had sprung up on every side; lots were staked off, and the whole section presented the aspect of a thriving and rapidly growing suburb.

What caught Ike's eye more than anything else, however, was.the sight of a neat real-estate office, and, noting that its occupants were strangers to him, he entered and engaged in conversation.

When he came out again he was like a different being. No longer did he seek to dodge or evade observation, but, hurrying back to town, paraded boldly along the main street until he had found a long-distance telephone-booth, where he shut himself up and was busy with the wire for more than an hour.

Then, emerging again, he strolled about in plain view, affably greeting old acquaintances, until it was time for the train bearing Ramsay Grant to arrive, when he joined the tumultuous throng assembling at the station.

Not long did they have to wait. On schedule time to the minute, the accommodation, puffed in, and from the steps of the rear coach descended the short, rotund form of the banker.

At first, he seemed unable to comprehend the meaning of such an outpouring of people; seemed rather dismayed than pleased at the shouts and cheering which greeted him. He appeared almost inclined to cut and run; but Isaiah Bender, who was acting as master of ceremonies, speedily reached his side, and explained matters.

"It's jest a leetle welcome our folks has arranged fer you, Mr. Grant," he said. "See," and he pointed proudly to an electric sign which hung between two posts just outside the station.

"Welcome to our benefactor!" it read.

Grant straightened up at the sight, and seemed far from displeased.

"Hum! Ha!" He pulled down his hat-brim and puffed out his chest. "Yes, I suppose I have been a benefit to the village in a small way, Bender; but I certainly did not expect such a cordial appreciation of it as this. It touches me. I may say, it warms up my very soul."

"Oh, we ain't begun yet," chuckled Isaiah. "Come on, Mr. Grant; I'll pilot yew to yer kerridge."

And then the astonished banker found himself escorted to a hack drawn by white horses and swathed in bunting, which fell into line behind the Vanceport Silver Cornet Band and led a lengthy parade over the entire village settlement.

The magnate could not restrain his expressions of admiration and amazement as he proceeded through the well-lighted streets and noted the evidences of prosperity and well-being on every hand.

Was this Vanceport, he kept wondering to himself, and ejaculated at almost every step, "Marvelous! Marvelous!" while Isaiah repeated with parrot-like exuberance: " Yew're to blame fer it all, Mr. Grant. Yew're to blame."

In turn, they inspected the electric power-house, the church, and the school-building, thus at last arriving at the "taown hall," where upon the stage "with scen'ry" was set out the semi-circle of chairs and the stand bearing a glass and pitcher of water which always s betokens "oratorical doings."

A chorus of school-children dressed in white opened the program by singing an ode especially composed for the occasion, and then each of the "leading citizens" made a speech, descanting with perfervid eloquence upon the glories of Vanceport and the manifold virtues and generosity of Ramsay Grant.

Finally, the central figure of the evening rose to reply. He was gracefully modest—some thought a shade too modest—in speaking of his own part in the village's improvement, alluding to what he had done only in the most general terms; but he came out strong in congratulating and praising them for what they had accomplished by their own unaided efforts.

"A year ago," he said, evoking a round of cheers, "I was seriously considering abandoning my summer residence in Vanceport; but now you have made it such a paradise that I could not be hired to leave."

This was all very well; but every one felt that something was still lacking. The audience remained in their seats, and the members of the committee in charge drew apart and conferred earnestly together.

At length, Isaiah rather hesitatingly approached the banker and plucked at his sleeve.

"Don't yew think it'd kind o' end up the perceedin's with a hurrah," he whispered, "an' send 'em all home happy, ef yew gave us a check naow?"

Grant turned upon him blankly.

"A check! A check for what?"

"Why, fer all these public improvements we've put in—the 'lectric light, an' the taown hall, an' the church, 'an the schoolhouse, an' the cement walk out to yer place—same's yew promised. I've footed up the totals so's to make it convenient fer you, an' the hull amount is twenty thousand eight hundred dollars."

But Grant waved away the paper which the other sought to thrust upon him.

"I promised that?" he said grimly. "And this is the reasdn for all this to-do to-night, and the hailing of me as a public benefactor? Why, man, you must be mad. I remember receiving a letter from you last fall requesting, me to contribute to some electric-light project you had down here, and promptly declining the proposal; but that is absolutely the only connection I have ever had with your program of improvements."

"What?" demanded Uncle Billy Gale, who, with the rest of the committee, had drawn near at the signs of an altercation. "Dew you mean ter say that yew didn't call us up from the Meterpolitan Op'ry-House in Noo York, an' after letting us hear C'ruso sing, tell us to go ahead with all these fixin's at your expense?"

"My dear man, I certainly did not call you up with any such message, and as for being at the Metropolitan Opera-House, I never was there in my life. Some one has shamefully imposed upon you!"

Isaiah Bender collapsed, speechless, into a chair. The banker threw himself back into a belligerent attitude, as though prepared to resist any unlawful assault upon his pocketbook.

The other members of the committee glowered fiercely at him, and the audience, which by this time had gained some inkling of what was taking place upon the stage, was in an uproar.

Just what might have happened, it is hard to tell; but at that moment Ike Somers stepped forward from the reporter's table, and, addressing Mr. Grant and the committee in a low voice, asked them to step aside with him a few moments, as he believed he could explain the misunderstanding which had arisen.

Then, recalling to the "leading citizens" the stormy night upon which he had been ejected from Bender's store, he told how his attention had been attracted on his homeward way by the clanging shutter at Ramsay Grant's.

He did not mention, however, the temptation which had assailed him, but contented himself by stating that when he saw how easily access could be gained to the house, and the telephone inside, he was seized with the idea of thus paying off his scores against Bender.

"My original purpose," he explained, "was by mimicking Mr. Grant's voice and pretending to be speaking from New York to raise Isaiah up into the clouds for a few days, and then drop him to earth with a dull thud; but we moved unexpectedly to the city, and in the hurry and bustle of our departure I completely forgot the matter."

"But why did you not explain afterward?" demanded Grant sternly. "You could have written."

"Of course I could; but it really never occurred to me that these timorous old grannies would actually go ahead on no stronger authorization from you than a mere telephone talk. When I found out for the first time to-day that they had actually done so, I was simply thunderstruck."

"And now what do you propose to do about it?" snorted the banker. "Do you know, young man, that you have been guilty of a pretty serious offense?"

"Ah, that is the point I was just coming to. Fortunately, I am in a position to make amends. I learned this afternoon that a commission appointed by the Governor, struck by the beauty and progress of Vanceport, has about decided to select our land north of the village as the site for an important State institution, and I have closed a deal disposing of it for forty thousand dollars.

"Now, I feel that this increase in its value is entirely due to the improvements started here, and in all fairness I should stand the bill.

"I impersonated you in ordering them, Mr. Grant. May I not take your place again in paying for them?"

But the suggestion seemed not entirely pleasing to the banker. The savor of public esteem had been sweet in his nostrils, and he was not exactly willing to step down from his pedestal.

He hummed and hawed and grew red in the face for a moment; then burst forth explosively:

"No, sir, you shall not. I've had the credit of doing these things; and, by the Lord Harry, I'm not going to resign it. Here, Bender, give me a pen, and I'll write you a check this minute."

Isaiah Bender, however, had not been cherishing the seed of civic pride in his breast all these months for nothing. It flowered out now into effusive bloom.

"They ain't neither one of yew goin' ter pay," he announced with dignity. "Vanceport is big enough an' great enough an' grand enough to meet her own obligations. We'll fix these things by addin' a mite to our taxes an' be beholdin' to nobody. Eh, boys, ain't I right?" he asked of the "leading citizens."

And among tne committee there was not a dissenting voice.

"But, say, boy," quavered Uncle Billy, still a shade incredulous, "ef yew sent that phone to us from Mr. Grant's house in Vanceport, haow in thunder did we come to hear C'ruso sing?"

"Oh, that was merely to make the deception complete," laughed Ike. "I saw a phonograph standing there in the room, and, slipping on a suitable record, let it do the rest."

"All right," said Uncle Billy. "I ain't a bearin' yew no malice; fer mebbe we'll have, a C'ruso an' a Meterpolitan Op'ry-House of our own right here in Vanceport some day. We've got the stage an' the scen'ry naow!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.