RGL e-Book Cover

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

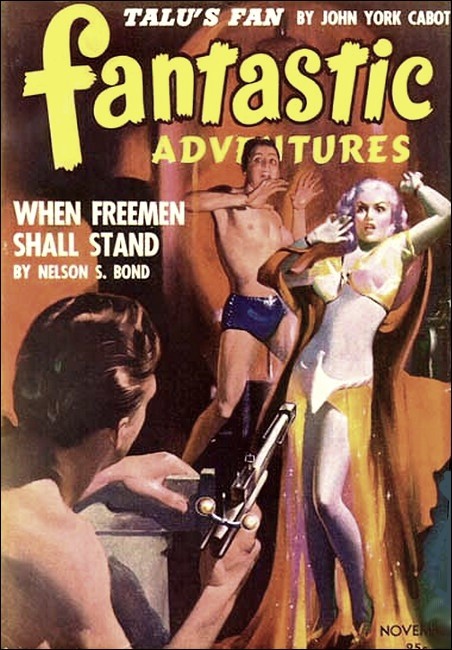

Fantastic Adventures, November 1942,

with "Sharbeau's Startling Statue"

"I swear if to you, Monsieur, as I stand there, the statue moves!"

It was a weird thing that was happening.

A statue that moved, and for a truly amazing reason!

MONSIEUR PAUL SHARBEAU is a friendly, amusing, easy going little man with the emotional temperament of a poodle. He has small, dark, dancing little eyes, the expected little black moustache—waxed at the tips of course—and an utterly blase disdain for the mysteries of life.

I was not surprised, therefore, to hear his voice coming excitedly over the telephone that night pleading shrilly that I come to his modest residence immediately for "some wine and ze convairsation." Not surprised even though it was after midnight and most normal people were in bed, Sharbeau had often, merely on impulse, called me at ungodly hours when he felt in the need for wine and companionship.

I was very much surprised, however, at his closing remark over the telephone when I had finally assured him I would be over as quickly as I could.

"Clee," he had concluded, "you know vairee much about ze occult, no?"

And before I had been able to frame a suitable reply to this, he had signed off.

"Zat is good. Zat is vairee good!"

I sat there looking at the telephone in my hand, the words still reverberating in my ears. Sat there frowning in perplexity over the fire-cracker conclusion of my little French friend.

Sharbeau's impression that I was an authority on matters of the occult had undoubtedly been born of several conversations we'd had in which I'd confessed that I had a cursory interest in things supernatural which amounted to nothing really more than a hobby. Been born of that, no doubt, plus the fact that I'd mentioned Poe to be my favorite author, and had myself turned out an occasional yarn of fantasy-horror.

I sighed, wandering irritably what on earth had been the cause of Sharbeau's sudden concern with a subject toward which he had previously expressed indifference.

Then I remembered that Sharbeau possessed an excellent wine stock which he had managed to smuggle out of France shortly after the Vichy sell-out convinced him his life would no longer be safe under German domination. Remembered, and forgot my irritation.

For excellent wine was excellent wine. Even at a quarter past midnight. And Sharbeau was an interesting enough chap conversationally, and might, after all, have unearthed some occult evidence which I might regret missing.

I thumbed my nose at the typewriter, put away the chapter I'd been polishing, and got my coat...

MONSIEUR SHARBEAU lived in an old brownstone

residence on the near North Side. One of those

buildings remodeled into spacious, four room,

kitchenette apartments. Sharbeau had converted one of

the rooms, the one with the wood-burning fireplace,

into a sort of library-study. We engaged in most of

our conversational and wine bouts there.

He met me at the door, obviously in a state of great agitation about something, and before I'd scarcely had time to remove my coat, he led me immediately into his study.

There was the ever ready bottle of rare vintage waiting on a thick, mahogany table between two glasses, and as I found an easy chair Sharbeau immediately placed a filled glass in my hand and poured himself a drink. His face was flushed, his dark eyes button bright.

"You will nevair believe what it is I 'ave to tell you," he said, downing his drink in jerky haste.

"Sit down and tell me about it," I suggested. I raised the wine to my lips, savoring the delicious bouquet before taking a sip. Rare stuff, and potent.

Sharbeau ignored my suggestion. He strode over to the mantel above the fireplace.

"Regard!" he said dramatically.

I followed his pointing finger. There was nothing atop the mantel but a stone statue—one that had been there on every occasion I could remember—some fourteen inches high. It was the statue of a Greek warrior in an attitude suggesting he was running.

I made my voice tactfully polite.

"It's a very nice statue. A very nice statue indeed. I've noticed it every time I've been here. Often intended to comment on it. What about it?"

Sharbeau closed his eyes for an instant, drawing in a shuddery breath.

"You notice nozzing unusual about it?"

I shook my head. "I don't know exactly what you mean."

"I mean since you are regarding it ze last time you are here."

Again I shook my head. "No, Sharbeau. I'm sorry. I never noticed it very carefully before. If something's happened to it, if it's broken, I'm terribly sorry."

Sharbeau seemed suddenly to realize his glass was empty. He stepped over to the table and filled it to the brim again. Once more he downed the liquid in a quick gulp. A strange procedure for one as fond of fine wines as my little friend.

He stepped back to the mantel, pointing a finger again at the statue. And again there was the same throbbing drama in his voice.

"Regard!"

I was getting badly confused.

"Perhaps you'd better be explicit," I said. "I told you be—"

"Ze limb of ze statue," Sharbeau said, "ze right limb, is forward!"

I saw what he meant. In the running attitude of the figure, its right leg was stretched out ahead of the left. But so what?

Sharbeau interpreted my expression. "Allllways," he said, "it was ze left limb forward!"

I perked up a little.

"Are you certain of that?" I demanded. "Are you positive that the left leg of that thing was always stretched out in front of the right?"

Sharbeau nodded. "But of course. I 'ave ze statue ten years. It is one of my favorites. I know every contour of it. Every line!"

His finger suddenly shot up to point to the face of the running figure.

"Regard!" he exclaimed again.

"All right," I told him instantly. "I see what you're driving at. What changes do you think have occurred in the facial expression of the statue?"

Sharbeau stared at me somberly. "Allllways," he said, "ze face smiles. Now it frowns ever so slightly!"

I smiled suddenly.

"And you want me to explain it?" I asked.

Sharbeau nodded.

"Someone, maybe a prankster, has switched statues on you," I told him. "That's the only explanation there could be."

Sharbeau gave me a clearly disappointed glance. He sighed. "I am sure you, ze great student of ze occult, would 'ave somezing sensible for to explain it." He paused to sigh deeply again. "And you give me stupid answers!"

I got a little impatient. Obviously my friend Sharbeau was a trifle drunk.

"Don't be so damned silly," I told him. "When there's a perfectly logical explanation for something it's stupid to try to pin it on an occult theory."

SHARBEAU seemed suddenly on the verge of

tears. He moved over to my chair and gripped my arm

with fierce intensity. Perspiration broke out on his

brow. His button eyes were pleading.

"But, Clee, it is not anothair statue!" he said with hoarse frenzy. "I am sure it is anothair statue, jus' like you are, until I check everywhere and find that there is no such stone as what this is made from anywhere in ze United State!"

Sharbeau was a trifle tipsy, but he wasn't in the babbling stage. He was sincere, I could tell. And if he had checked, if he had found out beyond a shadow of a doubt that this was the only statue of similar stone in the United States—then it seemed highly unlikely that such a prank as I had suggested would have been possible.

"You're dead certain?" I demanded.

Sharbeau released his grasp on my arm and stepped back, throwing his arms wide in a melodramatic gesture.

"Regard!" he demanded. "Do I, Paul Jacques Sharbeau, look like ze deceitful man? 'Ave I not allllways been on ze hup-and-hup wiz you?"

I admitted that he was the soul of integrity.

"Then I will tell you more," he said. "Tonight, shortly before I am call you, I find ze statue by ze table in ze study here, on ze floor, in ze completely changed attitudes I 'ave describe!"

"But—" I began.

Sharbeau cut me off, holding up his hand.

"I look on ze mantel, knowing it must be anothair statue put in ze place of my favorite statue which must be stolen! Voila—there is no statue on ze mantel. Ze statue on ze floor is ze only one!"

"Still—" I started.

Sharbeau once again cut me off.

"So I am convinced as first you were. I am know ze statue on ze floor is imitation of ze real statue. A prank. And yet," Sharbeau paused dramatically, "when I am pick up ze changed statue, I am see that, but for the vairee strange changes in left limb and right limb and facial expression, it is just like my own."

"Even so—" I started again. I got no further.

"I am remembaire," Sharbeau continued, "a vairee good friend, a dealaire in antique art and curios who 'ave once see my statue and tell me it is ze only kind of zat stone in ze United State."

"You made sure the stone in the statue was the same?" I asked.

"But of course," said Sharbeau. "I know ze texture, ze grain of it. Even wiz ze change in limbs and expression, ze texture and grain of ze stone is like alllways." He paused. "But rapidly I am calling ze art and curio dealer, am asking him is he certain what he tell me before about ze statue. He says yes."

"No chance, then, of this statue being a clever substitute," I concluded.

"None whatsoevaire!" Sharbeau said emphatically. "Now you believe me, no?"

I shook my head grudgingly. "Now I believe you," I admitted. "But, what you have proven is that that statue somehow moved, got down from the mantel, and started across the floor. The change in leg position most certainly points to the fact that it moved on its own legs and forgot to assume its former attitude when you walked in on it." Suddenly I stopped. Hand to my head.

Sharbeau looked at me in alarm. "What is ze trouble?"

"My God!" I exclaimed. "I've been talking about that statue as if, as if it were animated, alive, and, and—" I faltered.

Little Paul Jacques Sharbeau spread his hands expressively in an elaborate gesture.

"But of course," he exclaimed. "Zat is what I am trying so vairee hard to tell you!"

FOR the rest of the evening we discussed that

damned statue until we were blue in the face and more

than a little blotto from the wine. And from Sharbeau

I gained every atom of information that I could about

its history.

He had picked it up while in Greece. Bought it from a dealer who had claimed it to be centuries old and especially rare. No, there had never been anything strange about it during the ten years in which it had been in Sharbeau's possession. Never until this very night.

For my contribution to the discussion I vocally sorted through all the available information in the back of my mind dealing with the occult as related to statues or images. There was a surprising hodgepodge of stuff I'd gathered and long forgotten, but none of it seemed specifically to fit the purposes. Not a whit about living statues. It was pretty discouraging, especially to Sharbeau, who still had the fixed notion that I was "ze great authority" on anything supernatural.

The best I could do was a promise to barrage the Public Library and several private informational sources I had on such matters the first thing the following morning. Maybe there would be a clue.

Sharbeau, on the other hand, vowed to keep a closer watch on the statue and let me know the instant anything else inexplicable occurred to it.

When I finally rose to leave, I teetered a little drunkenly over to the mantel and stared broodingly at the stone image of the runner. There was something about it, something in the facial expression, which Sharbeau swore had once been smiling, that was defiantly determined.

It made me shudder, and I turned away.

My head was fuzzy, and I figured a cold towel on my face might be a good idea before leaving.

"Where's your bathroom?" I asked Sharbeau.

"Ze vairee first door on ze right," he told me.

MORNING found me, in spite of a slight

hangover, right on the Library steps the moment the

doors were opened. For the affair of the startling

statue was the first thing to enter my consciousness

on wakening.

And even as I ate breakfast and read the paper, my mind strayed constantly from my bacon and eggs and latest headlines, always ending up in a wrestling match with the eerie enigma to which Sharbeau had introduced me the night before.

I telephoned Sharbeau before heading for the Library, and his sleepy voice told me that he'd remained awake the rest of the night just on the chance that the statue might begin to prowl again.

Even though I told him to go to bed and get some sleep, I had a hunch that the little Frenchman would remain on watch before that stone statue until he'd one bottle of wine too many and passed into merciful slumber in spite of himself.

By noon I was finally positive that there would be nothing gained by any further canvassing of the Library. The files there didn't present a source that seemed to give the least hint of what I was looking for. I even took a long-shot chance and poured through a thick, dull tome on ancient Grecian sculpture. Sharbeau's statue was evidently not quite important enough to be listed in it, for it wasn't mentioned.

I couldn't get in touch with two of my private sources, and the other one proved to be utterly unenlightening. It took me the entire afternoon to accomplish exactly nothing.

Gulping a hasty dinner, I walked down Michigan Boulevard to Sharbeau's place. I had to ring the doorbell at least a dozen times before it was answered. And then a sleep-fogged Sharbeau, clad in the wrinkled remains of the suit he'd been wearing the night before, opened the door.

"Mon Dieu!" he exclaimed in horror, peering out past my shoulder. "It is night-time again, no?"

"It is night-time again, yes," I told him, stepping past him into the apartment.

"I was asleep, on ze floor of ze study," said Sharbeau, confirming what I'd already figured. "Ze wine, it must 'ave hit me shortly before noon. Ze bell ring and waken me."

"What about the statue?" I demanded. "Did it move again?"

Sharbeau blinked, then clapped his hand to his brow. "Mon Dieu—I do not know! I 'ave been asleep!"

He turned and hurried back into the study, and I was right on his heels. The place reeked of wine, and there were no less than eight quart bottles of the stuff, all empty, sitting around. Sharbeau had had quite a watch of it.

He came to an abrupt halt, emitting a gurgling cry, and staring down at the floor in horror.

Perhaps five feet from the door, in still a different posture from the one of the night before, was the figure of the stone statue!

"Well," I choked feebly, very feebly, "well!"

"Again it happen!" Sharbeau gasped.

"While you were asleep at the switch," I managed at last, "it went on the prowl again."

I felt a creepy chill along my spine. But I forced myself to bend down and examine this new posture of the stone statue.

The left leg of the statue was thrust forward this time. And just the night before, with my own eyes, I had seen the right one forward!

And the expression on the features of the image was changed also. Where it had been defiantly, scowlingly, determined the night before—in contrast to its former smile it was now much more markedly grim, much more resolute and fiercely, savagely determined!

Sharbeau had seen all this too.

"Mon Dieu!" he moaned softly.

I COULDN'T think of anything to add to that. I

stared wordlessly at the stone figure, my brain

wheeling madly but none of the cogs meshing any too

well.

And then something that might or might not have been significant occurred to me. I put my hand on Sharbeau's arm.

"Listen," I said, "was this, this runner facing in the same direction last night when you discovered him down from the mantel?"

Sharbeau nodded, uncomprehending.

"Toward the door?" I insisted.

"But of course."

"Is he any nearer to the door in this attempt than the first time?" I asked.

Sharbeau thought a moment.

"But of course. It is so. Vairee much nearer."

"Then," I declared, "we have at least something to work on. The statue is not just prowling. On each occasion it made for the door. It is trying to get out of here!"

Sharbeau reflected on this. "Oui, it seems so. But why?"

He had me there. And even though it was a reasonable question I was nettled.

"I don't know," I snapped. "Anyway, we've got a little more information than we started with."

Sharbeau nodded.

"Look," I said suddenly, "put your statue back up on the mantel where it belongs and go to bed and get some decent rest. I'll watch the thing until you relieve me. Then I catch a few hours sleep, here. You can wake me up when you're tired and I'll relieve you. That way we'll keep a constant watch. What do you say?"

Sharbeau nodded. "A vairee good idea, Clee." He picked up the statue and took it back to the fireplace, where he put it atop the mantel. He looked at it haggardly for a moment, sighed troubledly and turned back to me.

"What did you learn from ze Librairee?" he asked.

I told him the disgusting truth, which seemed to slump his weary shoulders even more than before. I realized, then, that if this thing wasn't cleared up within a damned short time, Monsieur Sharbeau was going to be a psychopathic wreck.

"Think I'll wash up," I told him, as he was shuffling out of his study to get his much-needed shut-eye.

"Ze first door on ze right," he said automatically ...

The hours I spent on guard in Sharbeau's study passed slowly, and the ash tray at my side was heaped with cigarette butts when midnight finally rolled around.

I sighed and stretched, suddenly aware that my eyes had been fixed in what amounted almost to a fuzzy sort of hypnosis on the statue atop the mantel.

I sat suddenly erect, straining my eyes into focus on the figure. No. Of course it had been my imagination. It hadn't moved. It was in precisely the same posture as when I'd taken post before it.

Only then was I really aware that Sharbeau's life wasn't the only one that was going to be messed up badly if this thing weren't figured out pretty damned quickly.

It was driving me quite a little bit batty. And I was finally getting wise to the fact. Cursing myself for ever having gotten involved in the weird mess, I rose, yawning, and went out to rouse Sharbeau and take over his bed.

He woke easily, for he'd had plenty of sleep by now. And after promising not to wake me until nine the next morning, he shuffled back into his study to take up the watch before the stone statue.

I was dead tired, and fell asleep to a whirling half-dream in which I did a stately gavotte on the White House Lawn with a stone statue that always wanted to run away. Sharbeau played the accompaniment for the dance on a bottle of rare wine which had been fashioned into a sweet potato whistle ...

SOMEONE was rocking the boat quite ungently,

and when I opened my eyes I blinked into the visibly

excited and tremendously elated face of my little chum

Sharbeau.

"I 'ave solved him. I 'ave solved him!" he was shouting. "Ze problem of ze statue is ovaire!"

I sat up, startled.

"Huh?" I gasped. "You mean—"

"I mean it is ovaire, forevaire!" Sharbeau cried, pulling at my arm excitedly.

I bounced out of bed, rubbing my eyes. My watch told me I'd been asleep three hours.

"Come to ze study!" Sharbeau insisted.

I followed him into his book-lined library, looking quickly around to see evidences of a struggle, of a broken statue. I don't know why, but these were the first things that came to mind.

I didn't see either. I just saw the statue, back on the mantel top where it belonged.

"It moved again," Sharbeau said, grabbing my arm and forcing me into a chair. "It moved again, and I, Sharbeau, am see it move!"

"But I thought—" I began.

But Sharbeau was bound and determined to tell this thing through to the bitter end. He wouldn't allow interruptions.

"It is get down from ze mantle!" Sharbeau said. "Right before my vairee eyes!" He sucked in his breath to emphasize this. "I am watch wiz horror. My throat she is filled wiz ashes. I cannot speak. My 'eart is pound pound pound. Ze stone statue climbs down from ze mantle like a living thing!" Sharbeau paused to roll his eyes.

"Go on," I demanded. "Good God, man. Don't stop now!"

"It is on ze floor, now," Sharbeau recounted. "I am still watch in choked horror. It moves toward ze door, in slow, difficult steps."

I closed my eyes, shuddering, getting a mental picture of that small stone creature moving laboriously across the floor while Sharbeau watched on, bugeyed.

"I cannot stand it," Sharbeau exclaimed. "I am afraid, but I cannot stand ze suspense. I force myself to step toward ze moving statue. Force myself alzo my soul cries out against it. I am bending down, reaching for ze moving statue, when it speaks!"

The words almost knocked me out of my chair.

"Speaks?" I bleated. "Good God, you don't mean s—"

"I mean speaks," said Sharbeau. And suddenly his face was wreathed in a reflectively happy smile. "And I am so glad ze statue speaks, once I am hearing what it has to say."

I was on the edge of the chair.

"What did it say?" I almost screamed.

Sharbeau cocked his head reflectively, as if making sure he was quoting the precise words of the stone statue. "It say, 'Only once in fifty years am I forced to do ziz. I had to speak. I could not be thwarted again.'"

I blinked, repeating the words. "Only once in fifty years was it forced to do this? It had to speak? It couldn't be thwarted again? It said that to you?"

Sharbeau nodded.

"But what was the meaning behind those words, behind the very moving statue itself?" I demanded.

Sharbeau held up his hand. He beamed. "Vairee simple, vairee simple indeed, mon ami. It is a wondaire we do not think of it before. The statue then ask me a question."

"A question?" I bleated.

Sharbeau nodded. "Oui. It is ask me this question. It is breathe it in my ear." He paused, his face coloring reminiscently. "I am blush wiz embarrassment, and it is all I can do to answer. But I am giving ze satisfactory answer, ze statue completes its mission, and now it is back on ze mantle like always before."

My glance shot up to the mantle. The statue was there, all right. There and exactly as it had been before any mysterious transformations had started on it. The left leg was thrust forward in the running position, just as it should be.

And the facial expression, just as it should be, was positively beaming with joy and serenity. Gone was the scowling frown.

I turned to Sharbeau.

"But the answer to his question," I demanded, "what was it?"

Sharbeau beamed.

"It was simple, as I say," he told me. "I am answer by saying to ze statue: 'It is ze vairee first door on the right!'"

I didn't say anything. I couldn't. I just looked at Sharbeau and up at the mantle where the statue now postured serenely. The very first door to the right, eh? Once in fifty years, eh? I glared at Sharbeau, and the glare slid into a squint of doubt.

Hell, the statue never moved an inch after that. And Monsieur Paul Jacques Sharbeau is an honest man, a person of integrity. And once again he has assumed his utterly blasť disdain for the mysteries of life.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.