RGL e-Book Cover

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Amazing Stories, May 1946, with "A Room With A View"

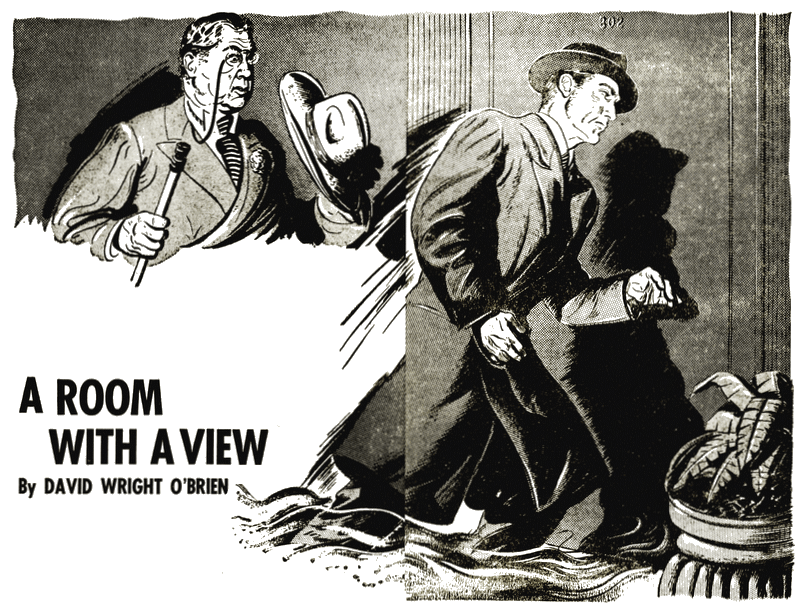

"I'm taking a look at what's behind that door, Senator!"

You could see things in this room. You could even see a

little fat man in a bedsheet and playing a fiddle—like Nero!

"THIS guy," said the Senator, poking his hard-chewed cigar butt in the air for emphasis, "has to think I am the tops."

"Yes, sir," I told the Senator.

The Senator waddled across the office and plunked his two hundred and forty pounds of worried statesmanship into the chair behind his desk. It creaked protestingly. The Senator pounded his ham-sized fist on the glass top of his desk.

"This guy has to be treated like the King of Siam," he growled. The frown furrows in his forehead became almost as deep as the canal-like creases separating his four chins.

I told the Senator I understood exactly what he meant.

"You ought to understand," he glowered. "You're my private secretary, aren't you? You ought to know if this guy isn't treated like—like—"

"The King of Siam," I broke in helpfully.

He glowered some more, nodded without gratitude, went on. "The King of Siam, he's likely to go back to our little old home state and tell everyone their Senator hasn't got what it takes any more. Then what would happen?"

I knew what would happen, but I let him continue.

"I'll be out of a job," the Senator thundered. "The voters will kick me out. And if I am out of a job you won't be needed as my secretary. I'll go back to working for a living in my law office back home. I'll have some fluffy dame as a stenographer, and I won't need any alert male secretaries like you around. Understand?"

"Yes, Senator," I assured him, "I understand."

"So get to work on it," the Senator concluded, picking up a telegram from his desk and glaring at it. "Get to work on it right away." He handed me the telegram.

I stuffed it in my pocket. I didn't have to look at it. I had read it fifteen minutes earlier. It was from a man named Joe Dinkle. Joe Dinkle was from the Senator's home state. Joe Dinkle was a mighty power in home state politics. Joe Dinkle's influence could win a sure re-election for the Senator in the state balloting two months hence. And his influence working the wrong way could send the Senator shooting out of his office like a rocket from a bazooka gun. It was very important that Joe Dinkle should decide to throw his weight in on the Senator's team.

The Senator was glaring at me. He punched his frayed cigar in my direction.

"Well, what are you waiting for? Get moving!"

I GOT moving. In the adjoining cubbyhole, which I

like to refer to as my own office, I got on the telephone.

I called any number of people. And I called a lot of

hotels. I wanted to find out if any of the people would

have any influence to get Joe Dinkle a room for that very

evening in any of the hotels.

One of the distressing things about the wire from Dinkle in my pocket was that it stated that he was arriving that very evening, and expected us—the Senator, I mean—to arrange for a hotel room for him, and meet him at the depot.

Arrange for a hotel room on about four hours' notice. Arrange for a hotel room in Washington, D.C.!

Half an hour later I was still on the telephone. I had removed my coat, I had removed my tie and opened my collar. I had mopped half enough water to float the Pacific Fleet from my brow. I hadn't been able to do a thing.

I had, in the last fifteen minutes, done my damnedest to throw the Senator's weight around to achieve my goal. Nastily, if it had to be that way, sugar-coated when that seemed to be best.

The people I got nasty with, got nasty right back and asked me who in the hell I thought I was. I told them I was speaking for the Senator, and they said so what. It was obvious that they knew the Senator was on the skids, and wouldn't take any guff from him. And if the rumor of the Senator's slide was so prevalent, it was all the more obvious to me that our entire future depended on making a pal out of Joe Dinkle.

The people I was nice to were evasive. I knew some of them could have helped, but they weren't wasting any favors on senators who would not be in office much longer. This again made me all the more anxious to please Joe Dinkle.

I spent another half hour that way, making futile phone calls and getting silly answers. And then I gave it up.

Joe Dinkle would be breezing into Washington, D.C. in exactly three hours, expecting a place to stay.

I got up and went through the door into the Senator's office. He wasn't there. An irritating habit of his, walking out without telling me, his private secretary, where in the hell he was going.

I glanced at my watch. Dinkle would be due in two hours and fifty-eight minutes. I'd have to meet him at the depot. The Senator had with a nice eye for the psychological effect, decided that it would not do for him to meet Joe Dinkle at the depot himself. It would look too much like the Senator was bootlicking Dinkle. He wanted to avoid that impression. Even though he was.

It would take about twenty minutes to get to the station. That left me—I glanced at my watch—two hours and thirty-six minutes in which to do something.

ONE hour and thirty-six minutes later I staggered

hot, footsore and bedraggled into a drug store telephone

booth. I had made the rounds of some fifteen square blocks.

I had offered bribes to bell hops of obscure hostelries, I

had punched doorbells, pleaded with apartment keepers, and

even scanned the barren columns of the flats-for-rent ads

in the newspaper.

The Senator was back at the office. He answered the telephone. He recognized my voice.

"Well, you get him a good hotel?"

I told him the truth. Then I leaned against the wall and listened to the profanity roll forth uninterruptedly for two full minutes.

"You—you numskull!" he concluded. "Didn't you make it plain that you were calling these people in my behalf?"

I gave it to him straight. "That was just the trouble," I said. "I might as well have said I was Himmler, calling to get a room for Goering, the friend of that big shot, Hitler. Your Crosley rating in this town just isn't, Boss."

That stopped his ranting. There was a much appreciated thirty seconds of hurt silence, in which I could envision the Senator mopping his statesmanlike brow like a ditchdigger.

"Good God, boy," he finally said, hoarsely, "we got to do something and do it fast!" I didn't try to answer that one.

"How about some of the—ah—smaller places?" he asked, after we'd both been silent a minute. "My status should—ah—impress them, shouldn't it? Can't you badger them into giving you a room?"

"I tried 'em all," I said. "I would have impressed them much more if I'd come bouncing into their lobbies on a pogo stick."

There was some more silence.

"Don't you have any ideas?" the Senator begged humbly. "Come on, boy. You usually bristle with ideas."

"Not on this situation, I don't," I told him. "There's only one idea I have, and I don't think you'd go for it."

"Let me have it," the Senator almost screamed.

"Give him your place," I said. "And you can sleep in the office."

There was a dreadful silence while this sank in.

"My place?" he husked at last. "My place?" His voice was pleading for me to forget the idea.

"That's the only solution," I said.

"But I couldn't sleep in the office," he groaned.

"You could call it pressing work that had to be completed," I said. "It would make you seem busy as hell."

There was another long silence. Then, in a voice suddenly too bright, the Senator exclaimed, "Capital! A brilliant idea, boy. It is positively fine. With only a minor change, it will be perfect."

"Minor change?" I demanded.

"Yes," he said, his heart of gold thumping rapturously. "You can sleep in the office, and I'll stay in your apartment."

"Room," I corrected automatically. "I don't have an apartment. I have a room." And then the old blackguard's nerve dawned on me. I almost blew up.

"I'll stay at your room, then," he said cheerfully. "You may sleep in the office. Dinkle will stay in my apartment, and we'll all be happy."

"Look," I said desperately, "I have a roommate!"

"That's no inconvenience," the old rascal purred.

"He plays a trombone!" I wailed, truthfully enough. "He practices all the time."

"A minor inconvenience," said the Senator. Then he rang off on me with a decisive click.

IT was forty minutes before Joe Dinkle's train

was due to arrive when I dropped back to the office to

clean up some last minute business. I found the Senator

there, stalking back and forth across the floor like a

caged she-lion in springtime. His eyes were wild, his huge

paunch heaving furiously, his famous flowing white locks

disarrayed from tugging.

"Thank God you got here!" he thundered.

"What's up?" I asked innocently.

"I went back to my apartment, to see that it was all in shape for Dinkle's arrival," the Senator boomed strickenly. "There were decorators all over the place, climbing up and down the walls like bees inside a hive. They were plastering and painting. The place reeks of turpentine. It makes you cry like onions. No one could stay there tonight!"

I sat down suddenly, sickly. We stared blankly at each other. And then the telephone rang.

I leaped to my feet and grabbed it up. "Hello," I said, and gave them an automatic this-is-the-Senator's office spiel.

"Yes," I found myself saying automatically. "Yes, Mr. Dinkle. I will relay that information to the Senator." Then, just as trance-like, I hung up.

I did my double-take, then.

"Good God," I blurted, "that was Dinkle!"

The Senator cut me into mincemeat with his stare.

"Say that again," he invited ominously.

"It was Dinkle," I croaked. "I was so knocked out it didn't register on me until he rang off."

"Dinkle is here?" the Senator inquired hoarsely, unbelievingly.

I nodded. "He said he made a mistake in his train time in the wire he sent you. He said he is waiting to be picked up at the depot."

The Senator's groan was agonizing to hear.

"Where will we put him?"

"The only place left," I answered, "is my room. It's dingy. The hall smells of cabbage cooking. My roommate plays a trombone."

"Badly?" the Senator asked dully.

"Horribly," I said.

He winced, and his complexion went a deathly gray.

"What do I do?" I asked.

He was suddenly on his feet.

"Pick him up at the depot, of course!" he rasped. "Pick him up and take him somewhere to stall for time."

"What then?" I demanded.

"I'll work on this thing myself," the Senator thundered. "I'll try every damned living place in the Capital. I'll do the impossible. I have to!"

I got out, then, leaving him ranting to the walls. It was foolish to try to catch a cab in front of the building, so I walked two blocks out of the way. Even then I didn't have much hope of getting a group cab ride that would get me to the station in the hurry I'd like.

I almost fell over in a faint when the taxi drew up along the curb in front of me. Almost keeled over dead when I saw that the cabbie was leaning out grinning and saying, "Taxi, mister?" as sweet as chimes.

I clambered into that cab like a high diver into a pool. I fished out my wallet, and with tears in my eyes flashed a ten on the driver and told him there'd be ten more if he'd wait half a minute for me at the depot.

"Sure," he said, throwing the hack into gear. "Glad to."

I settled back and lighted a smoke with hands that were as steady as a kite in an ack-ack barrage.

"You meeting somebody?" the cabbie asked, a block on.

"That's right."

"He gonna have a room reservation inna hotel?"

That was a silly question from a Washington cabbie. But it was the sixty-four million dollar one to me. I perked up from sheer surprise.

"No," I said. "God, no!"

"That's what I thought," my driver declared. "I know a good place. Real swanky. He can get a entire soot there."

I almost fell out of the seat.

"Say that again," I screeched.

He said it again. I was almost gibbering. Tears were in my eyes. I pleaded with him not to play jokes with me, begged him to swear that he was telling the truth.

"S'truth," he vowed.

"A suite?" I insisted. "An entire suite? Here in Washington?"

He said that was exactly what and where it was.

"Costs twenty-five bucks a day," he said. "Three room soot."

I was laughing and crying simultaneously, and the cabbie laughed to think he had touched me so deeply. I got out twenty-five dollars and waved it under his nose and told him it would be his when he took Dinkle and me to the place. We were a happy twosome when we got to the depot.

JOE DINKLE wasn't happy about anything, however,

when I found him next to the Men's Room where he said he'd

be waiting.

He was a small, wasp-faced man with a high collar and a derby and a coat with velvet lapels. I looked down instinctively at his feet to see if he wore button shoes, and so help me, he did.

His voice sounded like a nail file being scraped on a blackboard—high and screechy and unpleasant to the ears.

"Where is the Senator?" he demanded.

"The Senator has just been called in on an eleventh hour committee meeting," I lied. "His advice was needed badly. He's going to try to be in his office very shortly."

The lie seemed to work pretty well. I scooped up Dinkle's luggage, two bags and a paper-crammed leather portfolio. I told him I had a cab waiting, and hoped that I was telling the truth.

When we got outside the depot, I found the cab easily enough. It was parked where I'd left it, and the driver was telling all prospective customers to go away, he didn't want their business.

He beamed when he saw us, and reached back and threw the door open.

As we settled back in the cab, I could see that Dinkle had been impressed by the feat of holding a taxi against all comers. I took the opening to throw in a plug for the Senator.

"Anything the Senator needs in Washington," I lied magnificently, "he merely has to ask for."

It didn't go over so well. All Dinkle said was, "Hmph."

I told the cabbie to take us to "the address I gave you," and he caught on, gave me a broad wink which Dinkle fortunately missed, and we started off at last.

I tried to make talk with Dinkle during the ride that followed. It was a job that took all my concentration, since he wasn't providing much dialogue. Naturally, I didn't have a chance to pay any attention to where the driver was going, even though I was eaten alive by curiosity.

It was dark now, and all I know is that we made a lot of turns at a lot of corners and finally we were in a tree-shaded street and the driver was stopping beside a big, square, black stone building that looked somewhat like the sort of structure that houses a club.

The driver looked back.

"Here we are," he said, indicating the building by a jerk of his thumb.

"Oh," I said. "Oh, yeah." I looked around. The street was not at all familiar. I didn't even have the vaguest idea of what neighborhood we were in.

The cabbie got out, opened the door, grabbed Dinkle's bags, and started up the building walk. I scrambled out, and Dinkle and I followed him.

The front door was big and ornate. One of those wrought-iron grille jobs with a crest worked into the pattern. There was a bell pusher beside the door, and the cabbie set the bags down and pushed it.

I don't know if the bell had time to ring before the door was opened or not. At any rate, the door was opened almost instantly, and we were looking at a tall, cadaverous, unsmiling fellow with a bald head, pointed ears, and the uniform of a butler.

"How do you do?" he said.

The cabbie did the talking.

"A guest, for soot ten." he said, jerking a thumb at Joe Dinkle.

THE cadaverous butler nodded, not saying any more.

He turned and we followed him into a big, marble floored

lobby. At the far corner of the lobby there was a desk,

like they have in hotels. Behind it was a guy reading a

newspaper. All I could see of him was that he was wearing a

cutaway with striped trousers, and that the top of his head

showed patent leather shiny hair.

We were almost at the desk when he looked up from his newspaper, and we saw his face for the first time. It was a sharp-featured face, but rather pleasant. It had a moustache the tips of which were waxed, and a small goatee which was carefully trimmed and smelled of a fine gent's cologne.

The face smiled, dashingly, and personality radiated a million dollars worth all over us. I glanced at Dinkle and saw even he was impressed.

"How do you do, gentleman?" the guy at the desk smiled. "You have come for suite ten, I presume?"

I cut the cabbie off, wanting Dinkle to get the idea that the Senator's stooge had something to do with it.

"Yes," I said. "Senator—"

The guy at the desk cut me off.

"Of course," he interrupted. "I know. The Senator wants Mr. Dinkle to have our very best accommodations. And he shall have them, never fear."

I was quite a little bit surprised. How in the hell did this guy know I was from the Senator's office? And how in the hell did he know Dinkle's name?

But a quick glance in Dinkle's direction showed me that it didn't make any difference. Whatever it was all about, it was working like magic on Joe Dinkle. He was looking terrifically impressed.

I beamed.

"That's just fine," I said. "That's just dandy. The Senator wants Mr. Dinkle to have nothing short of the top." I turned to the cabbie and slipped him the twenty-five bucks I'd palmed.

"Thanks," I said. "We can carry on from here."

The cabbie touched his cap and left us.

"Take Mr. Dinkle's luggage up to ten, please," the guy at the desk told the cadaverous-looking butler.

A smooth purring elevator took us two or three floors up, then stopped on cushions of air. The self-operating elevator's doors then opened, and the cadaverous butler, carrying Dinkle's bags, led us down a richly carpeted hallway to an ivory-paneled door, the front knocker of which said, "Ten."

He slipped a key into the lock, the door swung inward, and we entered a room which was something out of a Hollywood movie set for class. It was the kind of drawing room in which rich guys are always showing etchings to smooth wenches. It was ultra.

The cadaver put down the luggage. He pointed to another ivory-paneled door. "Your bedroom is there," he said. He turned, pointed to another door. "The study is there, sir." Then pointing to another door, "And that is the bathroom. Is there anything else, sir?"

I slipped him a dollar and told him that there would be nothing else. He left.

DINKLE had been giving the room an approving

going-over. Now he sat down, evidently much pleased, and

gave me what he must have imagined was a smile.

"These accommodations seem rather comfortable," he said. "I had expected that there might be a little difficulty in getting connections, but I knew that—"

"A man of the Senator's importance and influence," I cut in, "can, when it's for someone he admires as much as you, do the impossible, Mr. Dinkle."

The telephone rang at that moment, and I leaped to the instrument, snatched it from its cradle.

The voice on the other end of the wire was familiar.

"Is everything satisfactory?" the voice inquired pleasantly.

"Why—ah—sure. Sure it is," I said. "Who is this?"

"Mr. S. Cratch, the manager. I met you down at the desk," the voice said.

"Oh." I recalled the pleasant guy with the waxed moustache and the cutaway coat. "Oh, sure, Mr. Cratch. Everything is fine. Just dandy. Mr. Dinkle seems very pleased. Thank you."

"If there is anything else you'd like," said Manager Cratch, "tell Mr. Dinkle not to hesitate to call."

"Sure," I said, "sure I will. Thanks." I hung up, turned to Dinkle. "That was the manager," I told him. "He says to tell you to call him if there's anything you'd like. He says," I lied, "that any friend of the Senator is an honored guest here."

Dinkle almost beamed. I felt pleased. I glanced at my watch.

"Are you hungry?" I asked. "Would you like me to get the Senator on the wire?"

"I am not hungry," Dinkle said. "I had a box lunch out of Pittsburgh that lasted quite a while. You may call the Senator, if you wish. Incidentally, did you inquire as to how much these accommodations of mine are costing?"

I winced. I knew Dinkle had a fist full of money. But his tight-fistedness was legend. Then I forced a hearty smile.

"I'll call the Senator," I said. "However, you are absolutely the Senator's guest during your stay here. These accommodations are his privilege to provide."

I went over to the telephone.

Mr. Cratch, the manager, answered at the desk.

"What's the address here?" I asked.

"1313 Styx Street," he said.

"Thanks," I said. "Let me have an outside line, please." There was a clicking, then I got an operator, I gave her the Senator's telephone number.

After a few moments of buzzing, he answered.

"Hello," I said cheerily. "Mr. Dinkle has arrived, Senator, and he likes the accommodations we arranged for him. You know, the ones at 1313 Styx Street."

"What the hell?" the Senator exclaimed. "You find him a place?" His voice was trembling with relief.

"Yes, indeed," I said, as Dinkle had an ear cocked. "We thought he'd like 1313 Styx Street, didn't we? Much nicer neighborhood."

"I get it," said the Senator. "I'm writing it down. How in the hell did you do it? He listening? Okay, I understand. I'll ask a cabbie to take me there. Never heard of the place."

"Neither did I," I said. I glanced at Dinkle, who was looking at me frowningly, ears still cocked on my conversation. "No, neither did I feel like eating right now. Mr. Dinkle would probably like to talk to you, Senator." I glanced at Dinkle, nodded. Dinkle rose, came over to the telephone. I handed the instrument to him.

"Hello," Dinkle said, "I am here."

I COULDN'T hear the Senator's answer to that highly

imaginative introduction. I wasn't interested in the rest

of the conversation, so I went over to an armchair by the

door and sat down.

Dinkle wasn't saying much except an occasional yes or no, and I gathered that the old boy was really handing him a honeyed line of guff. The Senator was good at that. He had to be.

I lighted a cigarette, staring abstractedly at the door. It was less than three seconds later when I realized that the knob of the door handle was turning.

I stared at it in fascination. It turned slowly, surely, and then pressure was being put on the door, and it was swinging slowly inward. Not stealthily, just slowly, matter-of-factly. I stared at it bug-eyed.

And then, as it swung wide, he stepped into the room.

By "he" I mean the little fat man in the bedsheet with the wreath of holly on his almost bald brow. He stood there, staring at me, then at Dinkle, who was at the other side of the room, busy on the telephone and with his back to this tableau.

The little fat man had pop-eyes that glittered wildly. He had an idiotic smile on his thick, pursed lips. Something made me glance down at his feet, and I saw they were clad in sandals.

For a shocked half minute I returned his idiotic stare with a stare of my own that was probably twice as slap-happy. Then the fat little man in the bedsheet spoke. His voice was a husky half whisper, which Dinkle, at the other side of the room and still oblivious to what was going on, couldn't hear.

"I beg your pardon," said the little fat man. "Really, I do."

Then he giggled softly, idiotically. And as suddenly and as noiselessly as he had entered, he was gone.

My head almost did a spin off my shoulders as I turned to see if Dinkle had noticed all this. Obviously he hadn't. He was still talking to the Senator, and his back was still to the door.

I let out a deep, whooshing breath.

Then I began to realize what had happened, and then I began to doubt what my eyes had seen. Suddenly, impulsively, I got up and opened the door. I stared out into the hallway.

Down to the left of the corridor, at a door on the very end, I saw my visitor of a moment or so before.

He was just entering a door off the hallway, probably leading into another suite. In his hand he had an object. The bedsheeted little fat man with the laurel wreath on his head smiled foolishly at me. He held the object in his hand aloft.

"I found it," he giggled.

Then he went into the end suite, and I heard the door close behind him.

The object he had held aloft was a fiddle.

I closed my eyes, took a deep breath, and stepped back in from the hallway, closing our door carefully.

When I opened my eyes, it was to find Dinkle staring at me in obvious bewilderment. He had finished his telephone conversation. I had no idea how long he'd been watching my antics in the hall. But it was obvious that he couldn't have seen the little guy in the laurel wreath and bedsheet.

"Is something the matter?" he demanded coldly.

I forced a silly smirk to my face.

"No. Oh, Lord, no," I lied. "I was just feeling a little faint. I stepped out into the hallway for a breath of fresh air."

DINKLE was staring at me hard, and it was obvious

that my explanation sounded silly to him. But he didn't say

anything. A moment later I wished he had said something,

and was still in the process of saying it. For the sound of

a fiddle came faintly but definitely to our ears.

A fiddle playing, mournfully, "I Ain't Got Nobody."

The silence between the two of us held. And the fiddle notes, screechy, faint, and awful, continued to seep into our suite. Like an idiot, I found myself thinking of the words of the melody.

"I ain't got nobody, and nobody cares for me. I'm so sad and lonely—". The words trailed off in my mind and I snapped out of it.

"That sounds," said Dinkle, "as if someone is playing a violin very hideously indeed."

I forced weak laughter.

"Heh, heh. Probably some comic radio show someone has on." I spied the Capehart sitting in the corner of the drawing room. "Say, that's a nice machine you have there. Let's get a decent program and drown that other one out."

Dinkle didn't say a word as I leaped across the room, turned on the big radio, and began to fiddle around for a station. After a few moments I was able to turn dance music on and up to a pitch where it drowned out the noise of the little fat guy's screeching fiddle.

"There," I said, looking up at Dinkle. "That's much better. What did the Senator have to say?"

Dinkle seemed to unfreeze a little. "The Senator is coming right over," he said. "He seemed to agree to the suggestion that we get right down to brass tacks and talk things over now."

"Oh," I said, "that's fine. That sounds like a swell idea."

Dinkle nodded coldly. "I think I shall have a nap while waiting for him," he said. "I think you may go, now."

That crack caught me slightly off balance.

"Why—uh," I faltered, "perhaps the Senator will want me for something. Ah—maybe I'd better wait until he comes. I'm his secretary, you know. You go right ahead and take your nap. I can have a smoke or two and sit here in the drawing room."

"Don't bother," Dinkle said, cutting me off neatly. He walked over to the radio, snapped it off. "I detest dance music," he said coldly. "Don't bother to wait. The matters I have to discuss with the Senator will not need an auditor. Thank you for meeting me at the depot. I have a splitting headache. Good-night."

It occurred to me, standing there foolishly looking around for my hat, that I had never been more thoroughly dismissed. It also occurred to me, with a sense of vast relief, that the fiddle playing had ceased.

I picked up my hat, made for the door.

"Sure thing, Mr. Dinkle. Whatever you prefer. Good-night."

Dinkle had already said good-night once. Twice obviously seemed superfluous to him. He watched me leave in tight-lipped silence.

In the hallway, I stood there a moment wiping the perspiration from my brow and trying to steady the trembling in my knees. The highly hellish frame of mind Dinkle was in, probably unknown to the Senator, was as unaccountable as it was grimly foreboding. Whatever had made him so suddenly crotchety was beyond my knowledge. But whether or not it was something I had done or something the Senator had said on the telephone, things definitely looked bad.

I pressed the button of the self-starting elevator, to bring it up to my floor. It went noiselessly into action, and, purring smoothly along, rose to the third. Someone was in it.

I stepped back, to let whoever was in it emerge. But I didn't step back quite far enough, for the occupant ran headlong into me on stepping forth.

I was conscious, first, of a body slamming into mine, then of an ugly oath, then of seeing a most queerly costumed guy squaring off and glaring at me with blazing ire in his dark eyes.

THIS guy was a lulu. He wore colonial-style

clothes. He had a powdered wig, atop which was a

tricornered hat. The big buckles of his shoes shone as

brightly as the wrath in his eyes.

"Sire," he snarled, "watch your way!"

"Now listen," I exclaimed, "I was—"

He cut me off. "Knave. Fool. Insolent ass! Argue with me, eh?"

And then, before I could dodge, he had slapped a leather glove but hard across my cheek.

When I was recovering from this, and ready to let fly with a haymaker, the guy in the foolish clothes shoved a card into my palm.

"Here, Sire, is my card. I, of course, demand redress. My seconds will call on you in the morning to arrange for the contest of honor."

And then, before I could catch my breath, the loony in the powdered wig and the tricornered hat and the colonial costume was striding off down the hall.

I watched him as he stopped at the door of the suite directly across the hall from Dinkle's. I saw him remove a key from his vest pocket, insert it in the door, and open it. Before he entered the suite, he turned to me and snarled,

"In the morning, Sire! You may select the weapons."

Then he was gone.

I was groggy as I entered the elevator, and still considerably dazed as I stepped out of it when it reached the lobby level. I looked dazedly around the lobby, and as things returned to focus, I saw the desk in the corner where the manager, S. Cratch, was sitting reading a newspaper.

There were plenty of questions I wanted to ask him. Questions about the sort of place he was running. I started toward his desk, and at that moment the Senator came pushing through the door into the lobby.

"Ah," the Senator boomed. "There you are!"

I hesitated. S. Cratch looked up from his newspaper. I glanced from Cratch to the Senator.

"How on earth did you ever do it?" the Senator demanded, bearing down on me. He was glancing around the lobby admiringly.

I decided to talk to Cratch later, and turned my attention to the Senator.

"He's upstairs," I said, meaning Dinkle, "taking a nap. You surely got here in a hurry. What made him so crotchety? What'd you say on the telephone that annoyed him so?"

"I found a cab right away," the Senator said. "Didn't have to share my ride with a soul. Never would have found this Styx Street if I hadn't had a smart cabbie. Never heard of the street before. And what's all this about Dinkle being in a state? He was plenty pleasant over the telephone."

I began to explain Dinkle's attitude toward me after he'd left the telephone, and while I was explaining someone else came into the lobby. I didn't pay any attention to this new entrant until I heard his voice.

"You left this in the back seat, mister," said the new voice.

I looked up and saw a taxi driver moving up to us. The same cabbie who'd found this apartment building for me. He was holding the Senator's briefcase in his hand. Obviously, I reasoned, he'd been the smart cabbie who brought the Senator to this address.

The Senator turned, smiled mechanically, took the case from the cabbie. I stared at him wide-eyed.

"Thank you, my man," said the Senator.

The cabbie recognized me, then.

"Hello, Mister," he said.

"You certainly get around," I told him. Then, to the Senator, I added, "This is the cab driver who brought me to this place. I'd never have found Dinkle accommodations if it weren't for this life saver."

"Well," the Senator beamed. "Well, I must say that—"

BUT the cabbie wasn't sticking around to listen to

his praises being sung. He was moving rapidly for the door.

So rapidly, in fact, that something made me suddenly and

unreasonably suspicious.

"Hey," I said, "wait just a minute, will you!"

"See you later, mister," the cabbie yelled. He was going through the door.

I started after him.

"Hang on," I shouted.

"What on earth is going on around—" I heard the Senator snorting, then I was shooting through the door in the wake of the cab driver.

"Listen you!" I yelled, as I raced out onto the sidewalk.

But there wasn't any cabbie in view. And neither was there any cab. In less than four seconds both had vanished. Even a combination Jesse Owens and Barney Oldfield couldn't have leaped into the hack, thrown it into gear, and roared off in split-second speed of that kind.

I stood there staring up and down the street like an open-mouthed idiot. There just wasn't any answer to the enigma.

When I got back into the lobby, the Senator had gone. I had scarcely turned toward the desk, where that worthy manager, S. Cratch, sat serenely, when he spoke up.

"Your friend, the Senator, has gone up to Mr. Dinkle's suite," said Cratch amiably. "He told me to tell you to wait here for him. Why don't you have a chair and make yourself comfortable?" He pointed to a deeply cushioned armchair near his desk.

I ignored the armchair. I advanced toward Cratch.

"If you don't mind," I said, "there are a few questions I'd like to ask you about this place."

He smiled cheerfully. His waxed moustache wrinkling personality and his goatee seeming to shine forth its cheer.

"Not at all," he said. "Not at all. Feel free to ask me anything you like."

I moved up to the desk. "Okay," I said. "Gladly. First of all, what sort of a place is this?"

He seemed puzzled by my question, but he was still smiling most affably as he answered, "Why, this is an apartment house. Sort of an apartment hotel, on club style, you might say. It is, I am pleased to say, very little known and highly exclusive."

I don't know what answer I'd wanted, but that wasn't it.

"Maybe I'd better start all over," I told him. "Maybe I'd better ask you what sort of guests you have here."

"I don't understand you," he said. The perplexity on his face deepened.

"I ran into two of your tenants just a little while ago," I said. "On the third floor, where Mr. Dinkle has his suite. One of them was wrapped up in a bedsheet with a wreath on his head. He was looking for a fiddle. The other one was dressed like a picture of an early colonial settler. He slapped me in the face with his glove and walked off muttering about my having my choice of weapons. Now, tell me truthfully, what goes?"

Mr. Cratch seemed highly puzzled for a moment, then his face broke into a wide grin. He started to chuckle, and the chuckle grew heartier until it was a full sized laugh.

I STARED at him like a goof while he doubled up in

merriment. Finally he began to calm himself down, coughing

and wiping the tears of laughter from his eyes. At last he

was able to make words.

"Excuse me," he spluttered, "for being so rude. I didn't mean to laugh like that, but I really couldn't help it. It was funny, you know!"

"Funny?" I demanded indignantly.

"Yes," he said. "You see, one of the tenants is giving a costume party this evening, He invited a number of the guests. You undoubtedly ran into two of them."

"But this one," I protested, "who smacked me on the cheek with his glove. That wasn't in order!"

He stopped smiling, looked instantly solicitous.

"I'm dreadfully sorry about that. The gentleman was quite obviously under the influence of liquor. I'll secure an apology from him in the morning, if you like."

"Never mind," I said. "Maybe all of us have a few too many now and then. Only he shouldn't have gotten so rambunctious. After all, I wasn't bothering anyone."

"Certainly you weren't," Cratch said sympathetically. "I am really deeply sorry that anything like that should have occurred. Was there anything else you wanted to ask about?"

I was so conciliated by the suave S. Cratch, that I almost told him there wasn't. Then I remembered the sixty-four dollar question.

"Say, one thing more," I said. "What about that cab driver?"

"Cab driver?" Mr. Cratch asked.

"Yes, the one who was in here a few moments ago, returning the Senator's briefcase. He was the same guy who steered me to this place a little while back, when I was tearing my hair out to find a place for Mr. Dinkle to stay."

"Oh," said Cratch noncommittally. "Is that right?"

"That's right," I said impatiently. "That's plenty right. And what I want to know is simple. Is that cabbie working as a renting agent for a swank joint like this? Or is he a hustler for the place? What goes?"

S. Cratch looked hurt.

"Really now," the dapper, personality-plus manager protested, "that is certainly a rather uncomplimentary question, isn't it?"

"Complimentary or not," I said, "what's the tie-up between this place and that hack driver?"

Mr. Cratch sighed, still showing wounded pride.

"Did it ever occur to you," he said with weary patience, "that everyone in Washington these days is a self-styled renting agent? Cab drivers, taking people to and from depots and in and out of dwelling places, have a better than usual chance to see what is available and what is not. Your cabbie in question probably took our most recent tenant to the depot, learned that he was vacating his suite here, and spread the word to the first person he encountered who seemed in need of accommodations. You tipped him well for it, did you not?"

"Sure I did," I said. "Plenty."

Mr. Cratch shrugged, spread his delicate, well-formed hands expressively, and smiled gently. "You see," he declared. "He gave the information to you and profited well from it. What more could you expect? He's probably sold similar information about other possible vacancies in other buildings a hundred times. Is that not reasonable?"

GRUDGINGLY I had to admit that it was reasonable.

But there was something else on my mind, something more

than vaguely disturbing, for which I didn't think the glib

Mr. Cratch could summon any reasonable explanation.

"Look," I said. "When Dinkle and I first came in here you knew we were friends of the Senator's, and you knew Dinkle's name. I was so excited, at the time, at getting Dinkle situated, that I let it slipped my mind. But I'd like you to explain that one."

"Well," Cratch smiled winningly, "one who has been in Washington as long as I, and one who has frequented the government offices as much as I, should be able to recognize most of the senators and their private secretaries. I've seen you around the Senator's office building many times."

"But Dinkle," I said, blushing like an ass at the flattery, "—you didn't explain how you knew his name. You haven't seen him around Washington. Don't tell me that."

Again Cratch smiled. "I have visited the Senator's home state, and my remarkable memory for names and faces brought Dinkle's to my mind. It took me perhaps three or four seconds to recall that he was a sort of political figure in your state, and was named Dinkle. His pictures appear in the papers of your state frequently, do they not?"

Giving the manager the benefit of the doubt on one of those not uncommon remarkable memories, it was all pretty reasonable to believe. I realized this much instantly. Yet there was one thing more. Where in the hell had that taxi gone? How had the driver done such a slick vanishing act?

S. Cratch must have read the expression on my face, for he asked, "Well, is there anything else?"

It would have sounded too damned silly to put into words. I made up my mind to skip it.

"No," I said, "there's nothing else. Nothing at all."

He gave me a flashing smile, the old personality poosh again. It had the strange effect of working, in spite of the fact that I knew it was strictly on a for-the-customer basis.

"I'm glad to have been able to clear up your difficulties," he beamed. "After all, quite frankly, this establishment appreciates the patronage of the Senator and his Washington guests."

Coming from a guy who claimed to be a Washington authority, that last crack set me back on my heels. He should have been wise to the fact that the Senator was, at least temporarily, a wrong number around Capitol Hill. However, if he hadn't caught wind of the yards, yet, so much the better. It was good to have someone thinking that your boss was still a big shot for a change.

I went over to a comfortable armchair and sat down to wait for the Senator. After about half a dozen cigarettes and an hour and a quarter later—during which time I did a lot of praying to myself and S. Cratch continued to read—I heard the soft whirring of the self-operating elevator and all of a sudden the Senator was stepping from the lift into the lobby.

I was on my feet and pointing as eagerly as a hunting dog. I almost wanted to scream for joy at the sight of the smug, pleased, mouth-full-of-feathers expression on the Senator's face.

I almost fell on my face, crossing the marble floor to him.

"Okay?" I blurted. "Everything okay?"

The Senator shot a quick glance at the desk, where Mr. Cratch was still buried in his reading.

"Perfectly okay, my boy," he said triumphantly. "Things could not be any lovelier." He glanced again at Cratch. "Let us go outside and search for a cab. If the night is still pleasant, we can walk back to my place, eh? We can celebrate over a few drinks of that special pre-war Scotch I've been saving."

He didn't have to say another word to convince me that everything was, indeed, super-specially rosy.

OUT in the street, the Senator said:

"You were right about Dinkle's mood being foul, m'boy. He was as touchy as a mother tiger when I got up to his suite. But I—ah—soon placated the troubled waters with a bit of—ahem—oil. In a little less than an hour and a half, m'boy, I had him eating out of my hand. There was a deal made, and we parted the warmest of friends."

"A deal?" I asked.

"Certainly," said the Senator. "Nothing rancid, however. My ethics would have stopped me from anything of the sort. And Dinkle, as you know, is a great church leader, a power with the highly moral vote in our fair state. No. There was nothing dirty about the deal we made."

"What sort of deal?" I pressed.

"An appropriation for a government building subsidy and land purchase," the Senator said. "As senior senator from my state I can say what land is to be purchased, and what building is to have essential priority."

"What's Dinkle's interest in it?"

"The moral interest. The church interest. I told you he controls the decent votes of the state. He wants an orphanage and several educational institutions constructed."

"Ahhhh," I said. "And you agreed to get it for him?"

"Naturally," said the Senator. "And on the site he has suggested. It will bring Dinkle and all his righteous voters right into my camp."

"Whew," I snorted. "So that was all he wanted!"

"That was all," said the Senator. "His attitude was hostile, no doubt, because he thought he could frighten me into complying with his request out of terror, if no other reason."

"We sure did a lot of worrying over nothing," I said.

"Not necessarily," said the Senator.

"I don't get you," I told him.

"I was planning before he arrived, to vote against the orphanage and the land purchase."

I whistled. "Thank heaven he came down here."

"Quite," said the Senator.

We'd walked about three blocks during our talk, and quite suddenly the Senator spied a taxi. He hailed it, and, miracle of miracles, it stopped to pick us up.

The Senator gave the address of his place, and I licked my lips in eager anticipation of some of that pre-war Scotch.

"LIKE it?" the Senator was asking, as I raised

the glass to my lips and settled back in one of the thick

leather chairs in his apartment.

"I love it," I said, sipping slowly. "It's ironic, isn't it, that your place here was cleared by the decorators in time after all? I mean, after we finally got a place for Dinkle."

The Senator smiled affably.

"I don't even mind the faint reek of turpentine that pervades the atmosphere," he said. "This is really a time for celebra—"

The ringing of the telephone made him pause. He put down his glass, picked up the telephone.

"Oh, hello, Joe, old man," he said jovially, winking at me. And then the jollity slid from his face like jello from a tilted platter.

"But, Joe!" he protested a moment later. "You can't believe that lying—"

The Senator stood there, staring open-mouthed at the phone in his hand. Then he put it back in the cradle. His voice was shocked and amazed as he turned to me and said:

"It was Dinkle. He's boiling. He just rang off on me!"

I was on my feet like a whirring gadget.

"What happened?"

"McCracken," the Senator said dismally.

I winced. McCracken was the junior congressman from the Senator's home state. McCracken was of the opposite political party from the Senator. McCracken was being groomed to run for the Senator's job in the coming elections.

"McCracken called Dinkle. Or Dinkle called McCracken. I don't know which. Probably the latter. But that isn't important. What is important is that McCracken told Dinkle I was never for the bill he wants, that I don't have any influence to push it through and that he, McCracken, can guarantee to deliver the goods for him."

"And Dinkle believed him?" I asked.

"McCracken read an excerpt from a statement I made in a Senate pre-discussion of the orphanage bill. It sounded like I was against it at all costs. Dinkle knew nothing of that statement until McCracken brought it to his attention. Now Dinkle is fire and fury. He won't believe anything I say!"

The pre-war Scotch suddenly tasted bitter. I put the glass down.

"Let's get going!" I said.

The Senator seemed in a fog. "Eh?"

"To see Dinkle, fast," I said. "Come on!"

I didn't have time or inclination to be surprised at the fact that we caught a cab without a moment's delay in front of the Senator's place. And I was willing to forget, temporarily, the fact that the cabbie was the same guy who'd delivered both the Senator and me to Dinkle's quarters on two occasions.

"You probably know where we want to go," I said. "Get us there in a hurry."

The cabbie just grinned and said, "Sure, mister."

WE got there in a hurry. I think the wheels of the

hack touched the ground only for turns during that mad

ride. I slipped him a bill as we piled out of the cab, and

we rushed into the lobby of the building, straight across

the marble floor to the elevator, and pronto up to Dinkle's

floor.

We double-timed it down the corridor to his room, the Senator game, but wheezing badly a good five yards behind me. I was first to the door, and I did the first knocking.

"Oh, Mr. Dinkle," I shouted. "Mr. Dinkle!"

There wasn't any answer.

"Mr. Dinkle!" I repeated, louder this time.

The Senator pulled at my elbow.

"Try the door," he suggested.

I turned the knob and pushed inward. The door opened as easily as a woman's mouth.

I stuck my head through the opening, looking around. Dinkle's things, his luggage and his suit-coat, were still in evidence. Some papers were messed around on the desk in the corner. The Capehart was playing soft music. But there wasn't any sign of Dinkle.

Figuring he might very conceivably be in another and more secluded room, I raised my voice again.

"Mr. Dinkle," I yelped.

There still wasn't any answer. I turned to the Senator. He was looking as worried as I felt.

"That's funny," I said.

"Is it?" the Senator asked acidly.

"I mean,"—I was getting flustered—"where in the hell can he be?"

And then we heard the violin screeching off down the hallway. The instrument, the manner in which it was being tortured, and the tune were all familiar to me. The tune was "I Ain't Got Nobody," and I had a mental picture of a fat little guy in a bedsheet sawing it off.

"Come on," I told the Senator. "I have a hunch. It isn't a very nice hunch, but come on!"

He followed me as I raced out of Dinkle's suite and started down the corridor. The music, if you could call it that, was still going on, and getting louder as we neared the room it came from.

It was the room I'd seen the bed-sheeted nut enter earlier in the evening, and when we stopped in front of the door we smelled the smoke.

"Something's on fire!" the Senator exclaimed.

I saw the wisps of smoke trailing out beneath the crack in the bottom of the door, then. Tiny, swirling tendrils.

Ominous as hell. The Senator was coughing.

The violin still played. I pounded on the door.

"Hey," I shouted, "open up here."

The music halted momentarily.

"Open the door!" the Senator boomed. "Something's burning in there!"

The music started up again. I ain't got nobody. Nobody cares for me. It was hideously off-key.

THE smoke was getting considerably thicker. I

kicked on the door with my feet, and immediately regretted

it when I almost broke ten toes.

The music stopped.

"Dinkle," I yelled. "You in there, Dinkle?"

There was a grunting moan that might have been meant for an answer.

The Senator give me a glance of horror.

"What's this all about?" he demanded hoarsely.

"Run down stairs," I said. "Get the manager. We've got to get into this room."

The Senator looked surprised, started to tell me to go myself, then turned away and lumbered off down the hallway at what he considered to be a mean speed.

The violin had started up again. The smoke tendrils were drifting up from the slit under the door in greater waves now, choking me and making me cough.

I pounded on the door again, but I knew nothing short of a key or a fire axe was going to get me into the place. The Senator had gone to get the guy with the key, so I started looking around for a fire axe.

There wasn't any; and by the time I'd proved this to myself, the Senator and Mr. Cratch tumbled out of the elevator and came running down the corridor to where I was pounding foolishly on the door again. The Senator was wild-eyed and wondering, and for once Cratch didn't look suave and self-assured.

"Damn him," said Cratch, "I can't imagine where he got the matches. We've always kept any incendiary materials away from him!" He was looking down at the smoke, and shoving the key in the lock.

At the sound of our voices, and the noise of the keys rattling, the violin stopped again.

The smoke was getting thicker. Cratch was having trouble with the key and was cursing roundly. We heard the sound of a window, opening inside the room.

And then Cratch got the door open.

We tumbled into the room, and started an immediate chorus of coughing. The smoke was so thick we couldn't see three feet ahead of us. I was right behind Cratch, and the two of us tumbled over the body on the floor.

When I regained my balance, I bent over to have a look at the body. It was very much alive, and writhing and squirming and coughing and sobbing. It was tied, hand and foot, with belts, towels, and torn sheets.

It was Dinkle!

The Senator hadn't seen him. He stepped around ahead of us and ran across the room to the open window.

"Good God!" he exclaimed. "Look!"

Cratch and I left Dinkle on the floor, leaped to the window. We stared out in the direction the Senator was pointing.

A bedsheeted little fat man was clambering along a pencil thin building ledge, one hand clutching a violin.

"Nero!" Cratch yelled. "Damn you, come back here!"

The little fat guy looked back over his shoulder and almost fell off the ledge. He giggled and then went on. He was nearing another window, and it seemed pretty clear that it was his idea to enter the building again through that window.

"Damn you, Nero," Cratch shouted, "you'll be sorry for this."

The little fat guy reached the window, kicked it through with his foot, and, hanging on with one hand, reached in and opened it.

"He's going into Aaron Burr's room!" Cratch exclaimed. He left the window and rushed, coughing, through the smoke and out into the corridor.

The Senator was looking at me wild-eyed.

"What the hell is this all about? Nero, Aaron Burr? What the hell goes? Where's Dinkle?"

I had forgotten Dinkle, and I suddenly remembered in horror.

I pointed to the writhing body on the floor.

"Good God!" the Senator exclaimed.

WE dragged the well-tied Dinkle out of the

smoke-filled room and into the corridor. Smoke was filling

the corridor, now, but it wasn't nearly as thick as in the

room.

I got the towel out of Dinkle's mouth, while the Senator untied his hands and feet. The little man was purple. Purple from near asphyxiation, purple from smoke poisoning, purple from the tight welts left by the bonds, purple with rage.

He stared at the Senator and me like we were something that had just crawled out of Adolf's moustache. His mouth was working and he was trying to say words, but he was spluttering too much from the fury that shook him to make any sense.

"I'll fix you. I'll fix you both!" he screeched. "Torturers! Madmen! Arsonists!"

"Look—" I began.

Dinkle stepped up and threw an unexpected and puny punch that caught me on the nose.

"I'll see that you're both put behind bars!" he screeched. "I'll sue you into poverty. I'll have the people of our state ride you out on rails!"

He was in no mood to be argued with, but the Senator stepped up to try. He didn't get a word in. Dinkle punched him in the nose. The Senator had a big nose and it began to bleed. He looked amazed, touched his nose, saw the blood on his hand. Then he reacted instinctively. He hauled off and smacked Dinkle on the jaw with a looping right.

The Senator was a big man, all his weight was in the punch. Dinkle collapsed as if his knees were wet spinach.

The Senator looked down in horror at the little man.

"Good God, what have I done?" he wailed. And then he turned on me. "It's your fault!" he bellowed. "You brought him to this madhouse!"

I stepped back a pace. "Now listen—" I began.

Then hell broke loose down the hallway.

There was yelling, lots of it.

"Fire!" most of the voices yelled.

Other doors along the hallway opened, and strange looking people were sticking out their heads and looking frightened. A little man in a bedsheet, clutching a violin in his hand, came racing down the hall. He was laughing wildly in a high, hysterical voice. He seemed to be having the time of his life.

"Fire!" he screamed. "Fire!"

There was a crackling that was ominous. It came from the room we'd just taken Dinkle from. I poked my head in the door. Window drapes blazed, and the smoke was enough to conceal a flotilla of destroyers.

I looked down the corridor. Smoke was pouring from the room that the bed-sheeted guy Cratch had called Nero had just emerged from. The bedsheeted fat guy had stopped in the middle of the hall. His face was ecstatic, and he was playing his violin.

Then Cratch appeared. He stepped up behind Nero, grabbed the violin from his hands, and brought it smashing down on the little fat guy's head. Nero went down and out for the count.

Cratch ran for us. His eyes were blazing and he was out of breath and out of aplomb.

"You'll have to get out of here," he said. "The flames will be beyond any chance of control in another ten minutes. Hurry, please. I'm sorry about everything. But please get out."

I grabbed him by the lapels.

"What's this all about?" I demanded.

He shook himself out of my grasp. "I thought it would be a good idea," he said. "But it didn't work out that way. I could have gotten twenty-five dollars a day for my extra rooms. This is awful. I was only trying to help out the housing shortage, make a little something out of it. Please leave. Hurry. Take that man with you." He pointed to Dinkle.

PEOPLE were running by us in the hallway. They were

in every state of attire and every type of costume. Fancy

dress costume balls seemed to be the order of the day.

Cratch shouted at them at the top of his lungs.

"Be calm," he yelled. "Don't rush. Make for the subterranean tunnel!"

Some of the chaos was quieted. The voices calmed down, but the babble carried on.

"Goodbye," said Cratch. "I have to get my records. Damn it, they're always being endangered by fire!"

He turned away and dashed off. The Senator and I stared at each other like a pair of idiots. The smoke in the hallway was now a lot thicker. Strange people in strange attire continued to mill past us.

"We'd better buzz," I said. I pointed at Dinkle. "You take one end, I'll take the other."

We dragged Dinkle into the elevator, got safely down into the lobby. We almost ran headlong into Cratch. His arms were filled with ledgers and account books. He nodded and moved on past us into the elevator.

We let Dinkle down on the marble floor none too gently. The Senator raced for the registration desk.

"What are you going to do?" I asked him.

"Call the fire department," he said.

"Make it fast," I said. "Or they'll be putting out our blazing hides."

It was then that I saw the little ledger a few feet from where Dinkle lay. It had been dropped by Cratch, obviously, for it was just like the ones he'd been carrying.

I picked it up.

"Unsettled Accounts," was the inscription on the cover.

I opened it. It contained names, lots of them, names followed by dates, and highly peculiar data. On the inside cover, written in a flowing hand, was an inscription reading, "Property of S. Cratch." It had a signature under it. The signature of S. Cratch, only it was a running together of the initial and the last name. "Scratch," was the way it was signed.

I came across the entry "Dinkle, Joseph," by accident.

Then the Senator lumbered up. His expression was one of complete bewilderment.

"You called?" I said.

He nodded. "They told me I was crazy. I said I wanted to report a fire on Styx Street. I gave my name. They said wait a minute. Then they told me I was crazy. Where in the hell did I think there was a Styx Street in Washington—that's what they asked me. There wasn't any such place, they said. I'm losing my mind. Let's clear out of here!"

We carried Dinkle out, each holding an end, like a sack of potatoes. The Senator's wallop had been quite an anesthetic.

The flames weren't apparent from the street, but smoke was pouring from a number of the windows. We carried Dinkle along for a block and a half. We stopped at a little baby park, plunked him on the ground, sat down on a bench.

"This is the end," said the Senator. "I'm through. You're through. We're all through. Dinkle will crucify us."

I had taken out the little book. The ledger that Cratch, or Scratch, had dropped.

"I don't know," I said. "Look at what I found." I handed him the book.

DINKLE stirred slightly and moaned. But he didn't

open his eyes.

The Senator was staring dully at the book, leafing idly through it and not saying anything.

"We've been through hell," I said. "Literally and figuratively."

The Senator handed me the book.

"I'm crazy," he said. "You're crazy. I know what you're thinking and it's the same thing I'm thinking. We're both as mad as hatters. Styx Street." He shook his head and shuddered.

"You didn't see Dinkle's name here?" I asked impatiently, shaking the book under his nose.

"Huh?"

I opened it to the page where Dinkle's handle started a column.

"Read this," I said, "and when Dinkle comes around we'll ask him some questions. Questions about slimy financial deals that swindled orphanages and churches. Questions about a lot of things you'll find in that account book of Scratch's."

Life came back to the Senator's eyes. They bugged out so far a stick could have knocked them off. Then hope brought the color back to his cheeks, and sheer elation followed.

"It can't be," he gasped. "It can't be! My god, man, this is wonderful!"

Dinkle moaned again. We looked down. He was opening his eyes, sitting up. Then he saw us, and he grew purple with rage once again.

"Hoodlums!" he screeched. "I'll—"

"Shut up!" The Senator barked. "Shut up. I've got a few things to say to you."

Dinkle's rage changed to a momentary amazement.

"I'm going to tell you a few things I've just found out about you, you lecherous little snake!" The Senator thundered. ...

THERE were considerably more than a few things that

the Senator told Dinkle. Things about Dinkle's hypocritical

past. Things about churches defrauded, orphanages milked,

widows impoverished. Lots and lots of things, with names

and dates and places.

When it was over there was no question as to the support Dinkle was going to give the Senator in the coming campaign. There was no question in Dinkle's mind that the Senator had better be re-elected to office, or else. And there was no question about Dinkle's coming reformation.

Dinkle had no idea of where the book came from. He only knew that it contained some awful truths. He didn't know that it had been compiled by a gentleman named S. Cratch, otherwise known as Scratch. A gentleman who managed a hot spot called hell, and who tried to turn a few pennies profit for himself by renting out a tiny section of it to relieve the Washington housing shortage.

No, the Senator didn't tell Dinkle that he'd found his name in the account book of Scratch himself. For then Dinkle might have learned about the final entry Scratch had put beneath his name. An entry that would have worried Dinkle into a too early date with the Devil.

"Due for permanent residence under my supervision six years from this date" was what that final entry under Dinkle's name said.

As the Senator put it—the day after he'd been re- elected—it was nice to be able to tell Dinkle to go to hell, and even nicer to know that some day he would.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.