RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

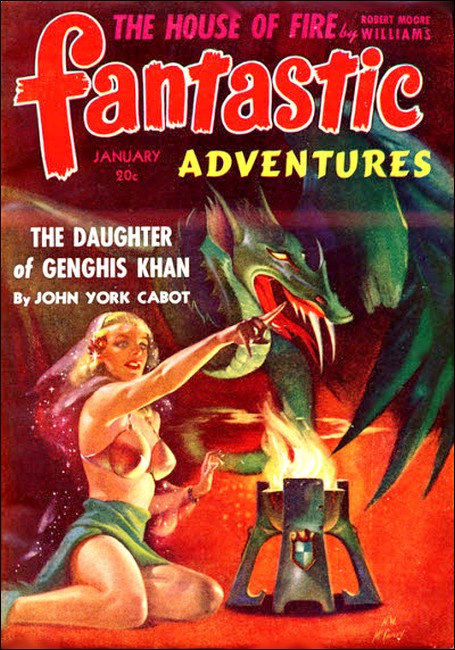

Fantastic Adventures, January 1942, with "Spook For Yourself"

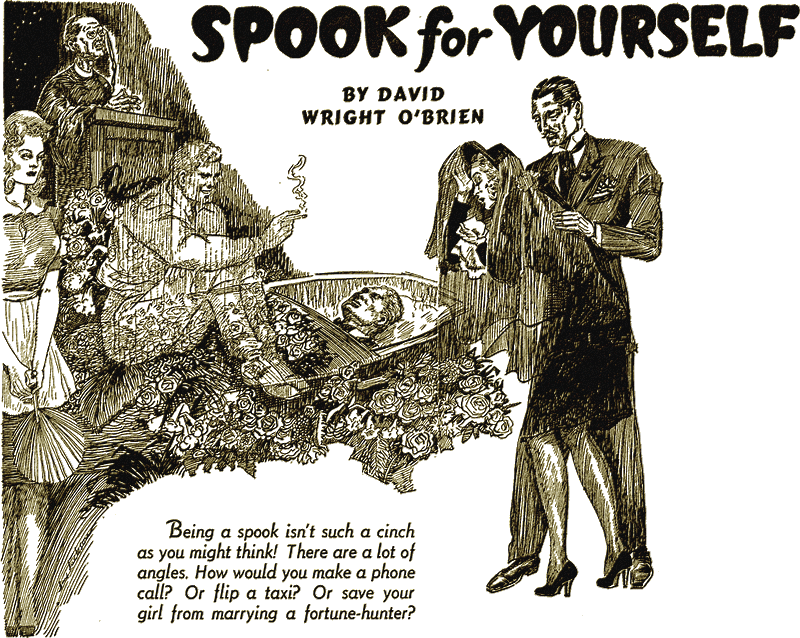

I sat down on the coffin to listen to the sermon.

"YOU'LL hurry back as soon as possible, won't you, Ronnie?" Jo asked me at the airport that morning. They were warming up my little sports monoplane, and I stood in the warm sun with my arm around her, looking down at the wonderful things the sunlight did to that rust-colored hair of hers.

"You know it, hon," I answered. "I'll be back with bells and baubles. Even the moon if you want it."

She grinned up at me, and her nose wrinkled in that elfin way. "I don't want that," she laughed. "But you will bring me something, won't you?" She put a slim finger to her pretty chin in mock contemplation. "How about four leaf clovers?" she decided. "Hundreds of them, for luck."

It was my turn to grin.

"Pick out something hard," I challenged.

"That'll be enough," she said. "But don't forget, hundreds of them."

"For luck," I promised. "For the luckiest, most wonderful marriage in the world the moment I get back." I saw the sports plane was ready, so I took her in my arms and said goodbye.

Minutes later, behind the controls of the ship, I looked down and saw a tiny red-headed girl waving a white handkerchief. Then the earth below resolved itself into an orderly cross-quilt of roads and farmland, and I was on my way.

TWO hours away from the airport, I was still thinking

about Jo and what a wonderful bride she would make on my return.

I hadn't been paying much attention to the instrument panel, and

so when the motor started coughing, and the foot pedals grew

sticky and hard to manage I was naturally startled.

I didn't have much more time to be startled, for in the next two minutes I found the ship out of control, the motor acting ragged, and the nasty problem of a sudden air pocket throwing me wing-down.

Thirty seconds later and I was fighting a terrific downward spin while the wind screamed through the vents of the cockpit cowling!

The spinning cross patches of earth rushed sickeningly toward me, growing larger and larger. There was no time for sweat or fear as I fought those controls to straighten the ship out of it. You can't bail out in the middle of a spin. Closer—all I could think of now was Jo.

There was a blinding, vast, incredibly engulfing roar—then blackness!

I STOOD there about a hundred yards away from the

crumpled, burning mass that was the little sports monoplane,

watching the smoke curl upward from the twisted wreckage.

I was scared stiff and my hands were shaking as I fished for a cigarette and lighted it. It was incredibly miraculous that I was unscathed—totally uninjured by the crash. I kept thinking of this and wondering how I'd gotten out of the wreckage, for the first realization I'd had was standing off from the plane watching it burn.

Sirens wailed—I'd crashed in a farm plot near a highway—and minutes later men were running across from the road, piling out of an ambulance, and dashing toward the wreckage.

They paid no attention to me—ran right by, in fact—and began working on the blaze with chemical extinguishers, while some of them worked dangerously in and out of the wreckage, searching for bodies.

It was then, of course, that I snapped out of my dazed stupidity and dashed over to the men with the extinguishers.

"Hey," I yelled. "Let it burn. There's no one in there. I'm the pilot, and I got out unharmed!"

I was less than five yards from one of the ambulance men with the extinguishers. He didn't even turn.

Now I grabbed him by the shoulder, hard.

"Hey," I yelled again. "It's all right. There's no one in there!"

And at that instant, two things hit me with stunning force. First, the chap acted as if he still didn't hear me. And second, from the corner of my eye, I saw three fellows dragging a body from the cockpit. My body!

IT is hard to get accustomed to the fact that you are

dead. It is even more difficult to adjust yourself to the

inevitable conclusion that you are a ghost.

These mental callisthenics—unpleasant though they were—were what I had to go through as I watched the ambulance people roar off down the highway with my body some fifteen minutes later.

I ran around like a chicken—or a ghost—with my head cut off during the time that they put out the blaze and carted my corpse off from the scene. I yelled. I howled. I protested. But, of course, no one paid the slightest attention to me.

They couldn't see me. They couldn't hear me. Even though I could hear and see myself and them quite clearly. At last I gave it up, and contented myself with glumly seeing the blaze put out and my body taken away.

Then I stood there on the highway, watching the cars flash past—some of them stopped to view the crash scene—and ruminating on the nasty position I was now in.

Oddly enough, I felt no sorrow for myself. Maybe that was due to the fact that, to myself, I was still myself. If you see what I mean. I still had cigarettes in the pocket of my sport jacket. I had a wallet in the opposite pocket. I could stand up, sit down, move around. Everything was pretty much the same to me—aside from being invisible and inaudible—but not to the world I'd left.

All things considered, my mental adjustment was proceeding at an incredible speed. And now, unhappily, I had room to think of Jo. Her face had been in my mind just before the crash. But now it was there even more strongly. For it had suddenly occurred to me that this would put an end to our plans.

Beautiful young ladies didn't marry ghosts. Or as far as I knew, they didn't.

But oddly enough, there was no maudlin sense of mourning in my soul at this realization. I felt an irritating frustration, of course. But this business of being dead, of finding yourself a ghost, wasn't the morbidly terrifying thing it is supposed to be. I felt—except for that sense of irritated frustration about Jo—pretty darned fine. I can't explain it, of course. You have to try things like that for yourself.

And even where Jo was concerned, I was suddenly determined to find some way to make the best of that. After all, I was a ghost, and ghosts are supposed to have supernatural powers and all that sort of thing. I decided to see what I could do about things.

The ambulance had roared off down the highway to the right, and so I stepped out close to the traffic lanes, and pointing my thumb in that direction, tried to hitch a lift.

If I hadn't been run over by a twelve ton truck, some five minutes later, I might have gone on trying to shag a lift indefinitely, unaware that no one could see me. But as I said, the truck thundered down at me, and before I could leap to one side, tore right into me—but through me!

This experience left me shaken but grateful. For if I hadn't been a ghost I most certainly would have been killed!

I CROSSED over to where a car was parked on the edge of

the pavement.

Its occupants were returning, chattering goulishly, from an inspection of my demolished monoplane. I climbed into the back seat and sat down just before they did.

A fat woman, with a plumed hat and gray hair, was one of the group. She was talking as they climbed into the car.

"It's horrible," she declared, shuddering. "That poor fellow never had a chance!"

She sat down on—or through—my lap. It wasn't uncomfortable, for in my status there was plenty of room for everyone, and I evidently didn't take up any space that they could use.

A middle-aged man, also fat, was driving the car. There was a younger fellow in the front with him, and a young woman and a baby in the back with the gray-haired old doll and myself.

Pretty soon we were rolling along in the same direction that the ambulance had taken. From their conversation I learned that it was Steuberberg, a fairly large town.

I smoked all the way, wondering vaguely what I'd do when I ran out of ghost cigarettes, and listening to their morbid chatter about my crack-up. It began to pall on me, and after a while I turned my attention to the scenery whipping by.

When we arrived in Steuberberg, I climbed out at the first gas station stop they made. There, checking the telephone book, I got a list of the hospitals in the community. Then I tore it up, for I recalled that I was more than a hospital case.

At a newstand, the first one I came to after leaving the gas station, I saw a headline.

"RONNIE SAYERS KILLED IN PLANE CRASH HERE!" it said.

That was satisfying. Even the people in Steuberberg knew who I was, or had heard vaguely about my being a prominent sportsman pilot. I felt a slight glow of personal pride, and followed a man for a block and a half while I read the news account over his shoulder. It was an irritating way to read a paper. But I found out what I wanted.

My body was being taken back to Brock City for burial on Friday. This was Wednesday. That gave me all of two days to get back there. Plenty of time. Even for a ghost. That's what I thought.

For the rest of the day, and straight through the following day and night, I had a maddening time trying to work my way back to Brock City. I hitchhiked, of course, because my first ride had been so successful that way. But I ran into snarls I hadn't expected.

Human hitchhikers had one advantage over ghost thumbers that I didn't realize till then. The human hitchhiker—who could make himself heard—was easily able to find out the destination of his driver. I was not so fortunate, and on at least six occasions was taken miles off my course by unexpected detours of the persons with whom I rode.

And on each occasion I was obliged to wait a chance to get out of the car at a gas station stop or thru-highway sign. It was all very irritating.

Then of course there were the two occasions on which I was forced to leave the automobiles of my unwitting benefactors because of the intrusion I felt I made on their privacy. In each case, my pilots were a young, amorously inclined couple. And in each case I felt acutely embarrassed. Those things happen to ghosts, you know.

On Friday morning, however, I at last arrived in Brock City. And promptly at ten o'clock on said morning, I sat on the edge of the pulpit in Saint Peter's Church, watching the crowds fill the pews for the beginning of my funeral.

UP in the loft, the organist was giving out with

majestically mournful rendition of the Funeral March, and up the

middle of the church, escorted by cutaway-clad pallbearers, came

my casket!

I could see the side-front pews. They were filled with a number of weeping, aged women. I couldn't recall ever having seen them before in my life. And I say life without meaning a pun.

A small, clerically garbed, white-haired minister stood at the front railing in the church, looking sad and righteous as the procession moved slowly along to the strains of the majestic organ.

I could see the faces of the pallbearers now. There was Wiffy Skene, my handball partner from the City Club. Wiffy looked very sad, and I could understand this inasmuch as we were to have played in the finals of the doubles championship four days hence. Behind Wiffy, also guiding the casket along with solemn sorrow, was big, blond Brad Noddinger. It was hard to understand why Brad looked so sad. He'd owed me over a thousand dollars in poker debts. He wouldn't have to pay them now.

The other pallbearers, of course, were also quite familiar to me. Some were good eggs, others—two at any rate—I thoroughly despised.

Then there was a small, mourning-clad group following the pallbearers. Most of their heads were bent, but I could make out the identities well enough.

Jo, of course, was the first to attract my attention. There was a momentary sharp, aching tug at my heart when she raised her head for an instant. She wore a black veil, and her face was white and determined beneath it. I wanted to run down the aisle, to put my arm around her and say, "Look, honey. Everything's going to be all right. Give me a smile, huh?"

She held her uncle's arm. He was a white-haired, red-faced old boy. Not a bad fellow. He looked sorrowful, and I couldn't tell if it was because of me, or merely due to the strain Jo was under.

On the other side of Jo, guiding her along, was a tall, black-haired, sharp-nosed chap named Duane Pearson. Pearson was a fraud, a phony, a louse. In short, I'd never liked him. He cheated at golf and snarled at his caddies. He was looking for a fortune to stick his paws to.

I had always suspected that he had a fondness for Jo.

Even though I'd like to have climbed from my pulpit perch and punched him on the nose, I stayed where I was. Gentlemen don't make scenes at their own funerals.

THE casket was finally at the front of the church, and

the mourners were seated in their pews. If I do say so, I'd

packed the house in this last performance. I felt a pardonable

rush of pride at this realization.

Suddenly I had to move over slightly in my perch on the edge of the pulpit, for the white-haired little minister was marching up the stairs to deliver his eulogy.

After looking up and down the packed church for a few hesitant moments, the little minister cleared his throat. Someone in the pews coughed. Far in the back of the church, a baby whined slightly.

"Friends," the little minister said solemnly, and I was amazed at the deep, rich power of his voice. "Friends, we are gathered here today on what, for all of us, is an especially sad occasion."

With no thought of being disrespectful, I pulled out a cigarette, lighted it, and settled back to enjoy myself.

"We all knew and loved Ronald Sayers," he declared.

"You might have loved me, but you never knew me," I retorted. But of course he didn't hear.

The old women in the side pews—the ones I'd never seen before—snuffled audibly at this.

"His passing," the minister went on, "has left naught but hollow emptiness in the bosoms of each and every one of us."

"Get on with it," I said, and again, of course, wasn't heard.

"Death is a dreadful thing," the minister observed.

"You're wrong about that," I challenged. "It isn't at all bad."

Of course the minister went right on.

"It strikes unexpectedly, swiftly, and finally. But it is the end to which we all must go sooner or later."

This was getting a little boring. Too many vague generalities. I stirred restlessly. So did a number of others in the pews.

The minister struck out on a new tack. I suspect that he sensed his audience slipping away.

"Ronald Sayers was a fine, clean, upstanding young man," he declared. And there was a challenging note in his voice I didn't like.

"No one who had any contact with him failed to love him," the little old man continued.

"Bosh," I snorted. He was painting me as wishy-washy.

"His works of charity, kindness, mercy, and love were known to all."

"At least the last named," I agreed.

"Ronald Sayers is not survived by any living relatives," said the minister. I thought of my drunken Uncle Pete, who was pensioned off in Tahiti, and who would be in as soon as he heard the news of my death, both paws grabbing for what was left.

"But there are many of us to whom Ronald was more than kin, more than a brother, more than a father," the minister asserted.

"Please," I protested. "Leave that stuff to Washington." I was beginning to feel a slight irritation that this windy master of vague generalities had been selected to preach my funeral sermon. I got up from my perch and silently slipped down the stairs while his voice droned on.

VAULTING the railing, I stepped over to my casket and

climbed comfortably atop, curling my arms around my knees. Now I

could concentrate on gazing at Jo, who was less than ten feet

away. I'd lost interest in the sermon by now.

Jo was bearing up well. Stiff upper lip and all that. This pleased me, for I knew she had courage, and the very genuineness of her white-faced restraint was stronger than a thousand tears.

I felt badly about not being able to tell her, of course. But there was still nothing I could do about things until I became thoroughly familiar with the powers and privileges of my new status as a ghost.

It was exceptionally irking, on the other hand, to watch Duane Pearson sitting beside her and patting her hand in solicitous understanding. Pearson and I had never gotten along well, although Jo had never been aware of this.

He had a small moustache beneath his sharp, long nose, and now and then he brushed it like a self conscious cat, looking out of the corner of his eye to see if people noticed how fine he was being about it all.

I wished then that ghosts could throttle people like they do in books. I'd have gladly choked Pearson into unconsciousness. But of course my gaze returned to Jo. And in my mind I tried to tell her things.

Maybe my mental wireless had some results, for I seemed to notice a strange change occurring in her. She was still white-faced, but the unhappiness in her eyes was replaced by a sort of hidden understanding. As though she heard me, and knew how I'd want her to feel. The time must have raced by, as I sat there atop my casket drinking in the loveliness of her. Time had always done that in the past when I looked at Jo.

But at any rate, before I was aware of it, the services were over and the pallbearers were leaving the pews and grouping around the casket while the organ picked up its funeral dirge once more.

I climbed off the casket and waited until Jo and the group of immediate mourners fell in behind it as they began to move out of the church. I walked along, then, right behind Jo, still sending out those mental telepathic messages. And they seemed to be going over better than ever, for I saw her little shoulders square, and her chin went up.

Pearson still marched beside Jo, and had I been able to, I'd have planted a ghostly kick on the seat of his well-tailored morning coat.

I STOOD at the top of the steps outside the church,

undecided, watching them put the casket in the hearse, and

looking a bit wistfully after Jo and the others as they climbed

into the long black mourner's limousines.

And it was then that they grabbed my arm.

When I say "they", I mean two other ghosts!

And when I say "grabbed my arm", I mean just that, for they were forcibly restraining me there on the top of the church steps!

They almost scared me to death—I mean out of my wits. One was a tall, heavy, red-faced fellow with a jovial air and twinkling eyes. The other was a little man, pinch-faced, skinny, yet somehow instantly likable. How did I know they were ghosts? Well they grabbed my arm, for one thing, and for another, the big fellow boomed.

"Hello, Brother Ronnie, welcome to our city!"

Somehow my wits returned.

"Who, what, how—" I began.

The big, fat, jovial, red-faced ghost grinned.

"A bit of a surprise, eh?" His voice was a boom. "Never occurred to you that there were other ghosts trooping around beside yourself, eh?"

"Yeah," said the skinny little pinch-faced ghost, "it never occurs to any of us."

"Nice funeral you've just had," the big ghost complimented.

"Thanks," I answered. "But look," my gaze flew down to the black limousine moving away from the curb after the hearse, the limousine in which Jo was riding, "I've got some things to attend to. If you two will look me up some other time I'm sure we can compare some interesting notes, and—"

"The rest of the funeral will get along by itself," the big ghost boomed. "My name is Manners. Brother Manners, if you wish."

"I'm glad to meet you, Brother Manners," I answered, trying to get my arm loose. "But you see—"

Brother Manners didn't release his firm grasp on my arm. "And the ghost to your left," he went on, "is Brother Bead. I know you'll be anxious to meet the rest of the boys."

"Look," I demanded frantically, "it's all very nice realizing I won't be lonely in my new life. But if we could put this off till some other time I'd—"

"Sorry," boomed Brother Manners firmly, "but this is as far as you're allowed to go."

"ALLOWED to go?" I was properly frantically

indignant.

"By the Royal Order of Brothers of the Shroud," big Brother Manners answered cheerfully. "Section two, article five. No ghost is allowed to follow his funeral procession further than the church services. It might be too depressing."

"Royal Order of Brothers of the Shroud?" I felt as if I were losing my mind.

"The International Ghost Union," Brother Bead piped up squeakily. "We're president and vice president of Local Nine, here in Brock City."

I could see that the hearse, followed by the long automobile procession, was now at least four blocks away.

"But you don't understand," I pleaded. "My girl, my fiancée, is in that procession. I want to be with her. I want to be able—"

"Plenty of time for that," Brother Manners boomed with sympathetic, but firm, understanding.

"Yes, plenty of time for that,"

Brother Bead squeaked in echo. They both still kept unyielding grips on my arms. I watched the last cars of the automobile procession turn a corner six blocks down.

"All right," I said resignedly. "What must I do now?"

"That's better," boomed Brother Manners heartily.

"Much better," piped Brother Bead.

"We'll just jump into a car," said Brother Manners, "and whip over to the lodge meeting. It's going on now. The brothers will all be glad to see you. We haven't had a famous member in our chapter for quite some time."

They led me down the steps, still holding onto my arms. A car was moving at a fair amount of speed past the church. Before I knew it, Brothers Manners and Bead had whipped me out into the street, and still holding me, had leaped onto the running board of the machine!

Brother Bead saw the expression on my face.

"Don't let it scare you," he said. "It's easy. There are lots of tricks you'll get to learn in a short while." And with that, they pushed me through the side of the car and into the back seat!

There were two people in the back of the car, and one person—a girl—driving in the front. We sat down on the two in the back seat, and Brother Manners pulled a package of cigarettes from his pocket.

"Have one?" he offered.

I reached over past the nose of the middle-aged man on whose lap I was sitting, and said, "Thanks."

We sat there, then, smoking and talking as the car rolled along.

"We might have picked a larger car," Brother Manners apologized with a wave of his hand. "But we're in a bit of a hurry."

"What's this all going to be about?" I asked. "I mean, this lodge business?"

"It's simple, Brother Ronnie," Brother Bead piped up. "You've got to meet the brothers before joining the association. Sort of a formal introduction, y'know."

"I don't mean to be rude," I told them, "but supposing I don't care to join?"

Brother Manners laughed in booming heartiness.

Brother Bead chuckled squeakily.

"You have to join," Brother Manners explained.

"All ghosts have to," Brother Bead added. "If they want to amount to anything."

"What good does it do me?" I insisted.

"You'll learn the tricks of your trade. You'll learn to spook for yourself, so to speak," Brother Manners explained. "We can teach you a lot. We can show you that we've got a pretty swell organization, and that this new life is finer than any other—especially the one you've just left."

"Somehow," I answered, "I feel already as if it is."

Brother Bead nodded.

"You get that hunch immediately. I know I did."

"How many members do you have?" I asked curiously.

"As many," Brother Manners waved his hand vaguely, "as there are good eggs who've died."

"You said good eggs," I replied. "What do you mean by that?"

"Not everyone who dies gets to be a ghost," Brother Bead piped up proudly. "Oh my no, not everybody."

"Well, well," I said, feeling as if it was all I could say, "that's something to be proud of, eh?"

"You bet it is," Brother Manners boomed. "Only people who die violent deaths, and who've learned to live well, and who are good eggs, can be ghosts."

"Well that does limit it a bit, I imagine," I told him.

"Yes," said Brother Bead, squeakily. "And you have to die under a certain age to be eligible."

"Fifty," said Brother Manners. "You have to be under fifty, in addition to the other requirements."

"I'm learning a lot already," I declared. "People have such silly ideas about ghosts in life, don't they?"

"They're superstitious," Brother Bead piped in reedy scorn.

The car in which we were riding was whipping along at a great rate of speed now, somewhere around fifty miles an hour. Looking out the window I could see we were still in the city, but traveling along a wide stretch of super boulevard.

"You'll find our lodge exceptionally mutually beneficial," Brother Bead declared. "I don't know what I'd have done without it. I tell you, when I died I didn't know a soul. Wasn't on speaking acquaintance with a single ghost."

Brother Manners nodded.

"We taught Brother Bead lots of things he'll never regret learning." He suddenly looked out the window. There was the Brock City municipal stadium a half a block away. "There we are," Brother Manners boomed heartily. "Might as well get ready to step out."

"You mean that's your lodge headquarters?" I gasped.

Brother Bead nodded.

"Certainly. It's very seldom in use more than once a week by humans. We try to arrange our meetings not to conflict with the regular schedules in the stadium."

"Although once or twice," amended Brothers Manners, "we've had to hold emergency meetings while prizefights and rodeos were going on."

I could only gasp. And just in time, too, for in the next instant we were passing the municipal stadium and brothers Manners and Bead were whipping me through the side and out of the car onto the street.

"Thanks," Brother Manners boomed after the car, bowing politely.

I was still shaken by the apparently effortless manner in which we alighted from the swiftly moving car. No jar. No jolt. I remember regretfully the countless miles I allowed myself to be carried out of the way, just a few hours back, in hitchhiking to Brock City. And at any time, it was now apparent, I could have stepped out of the car when my drivers turned off on side highways. I chuckled.

"What's so funny, Brother Ronnie?" Brother Bead asked.

I told him.

Brother Manners and Brother Bead laughed heartily at this.

"You see what we mean?" Brother Manners said. "You've a lot to learn before you can spook for yourself. All sorts of tricks."

"Heh-heh-heh," Brother Bead shrilled. "Think of it, waiting for a gas station before daring to get out!" This seemed to tickle him.

"Well," said Brother Manners, removing his paw from my arm, "we might as well get started."

THE three of us moved up to the sidewalk and headed for

the huge front doors of the municipal stadium.

There was a big sign on the front of the door, reading "LODGE MEETING TONIGHT. PROMINENT SPOOKERS TO BE HEARD!"

I stopped aghast.

"That sign," I choked.

"Yes?" Brother Manners said casually. "What about it?"

"Can't live people see it?" I demanded.

Brother Manners chuckled heartily.

"Of course not. It's a ghost sign. You'll learn about them."

Of course we walked right through the doors of the municipal stadium. It was very hard for me to get used to this neat trick of ghostery. But what we encountered just inside the doors was even worse. Three tall ghosts, wearing long gray shrouds, faces hidden by voluminous cowls, greeted us!

I stepped back, startled.

Brother Bead chuckled squeakily.

"Don't be afraid, Brother Ronnie," he said. "These are brothers. They're just wearing the lodge uniforms."

Silently, the three new "brothers" handed us three shroud-cowl outfits. And by watching brothers Manners and Bead I was able to don my costume over my street clothes without any particular trouble. I could hear a babble of voices coming from inside the stadium proper. Evidently the meeting was in full session.

It was, and I saw as much immediately upon stepping through the last doors and into the vast stadium hall. Almost all the main floor chairs of the stadium were occupied by hooded gray figures. And I saw that they were grouped around a prize-ring —there was evidently going to be a fight the following night—and enthusiastically raising hell.

Brother Manners touched my arm reassuringly.

"There they are," he said proudly. "A fine group, a great gang."

I noticed then, for the first time, that some of the "brothers" carried large placards—the kind you see at political conventions—bearing various legends.

MORE PAY AND SHORTER SHROUDS, declared one of the placards.

DOWN WITH SCAB HOUSE HAUNTERS, declaimed a second.

A third, and very windy placard asserted that, AMERICAN UNION OF AMALGAMATED CHAIN RATTLERS IS 100% BEHIND NATIONAL DEFENSE!

This was indeed reassuring, and I told Brother Manners so.

"We're a patriotic bunch," he declared solemnly.

OUR entrance was noticed for the first time, for there was

a burst of cheering and applause, as hundreds of hooded heads

turned in our direction.

Brothers Manners and Bead, throwing out their chests proudly, took me by the arm and led me down the aisle through the cheering throngs and up into the boxing ring.

There was a short, rotund, shrouded little ghost already in the ring, and Brothers Manners introduced me to him.

"Brother Wumpf, here, is our secretary. Brother Wumpf, meet our new brother, Ronnie Sayers."

Brother Wumpf extended a fat, cordial paw and grinned charmingly from inside his shroud.

"Glad to know you, Brother Ronnie," he said cheerfully. "I've been waiting to meet you. Have a nice trip?"

"Oh, jolly," I answered lamely. "Just ripping."

Then Brother Manners stepped to the center of the ring, holding up his arms for silence. Almost instantly, the ghost crowds subsided.

"Brothers," declared Brother Manners loudly, "we have with us this afternoon a new and rather famous member, Brother Ronnie Sayers!"

This was the signal for instantaneous and gratifying applause. Brother Manners let it continue for a while, then raised his arms again.

"He will be apprenticed immediately upon your approval. And we'll take a rising vote on the question." He paused. "All in favor of admitting the new brother please stand."

There was the sound of many shrouds sliding against wood as the crowd rose in unison.

"Fine," said Brother Manners, and the "yeas" resumed their seats.

"Now all those against the proposal," boomed Brother Manners.

No one rose.

Brother Manners turned, grinning from ear to ear.

"Welcome, Brother Ronnie Sayers. We're glad to have you!" he grabbed my hand.

The stadium broke into cheers. I blushed, shuffling a bit in awkward embarrassment, while successively, Brothers Bead and Wumpf gripped my hand. Now Brother Manners took my hand again, in a curious fashion, folding my fingers oddly.

"This," declared Brother Manners, "is the lodge grip." He paused solemnly. "Practice it and remember it. It will mean much to you in years to come."

I shook hands again with Brothers Bead and Wumpf, this time with the lodge grip. Everyone was very happy.

At last Brother Manners stepped up to the front of the ring again and spread his arms wide. And again the silence was quick in settling over the noisy crowd.

"Has all the business been concluded before our arrival?" he asked. There was a thundering chorus of "Yeesssss!"

Brother Manners smiled.

"Then I move we adjourn until the next meeting," he suggested. "All in favor please rise."

For the second time there was the sound of shrouds sliding against wooden chairs. All the brothers had risen as a man, or as a ghost.

"The ayes have it," trumpeted Brother Manners. "Meeting adjourned for the day!"

I TURNED to Brother Bead.

"This has been swell of you," I began, "and now, if you don't mind, I'll leave you for a little while to—"

Brother Manners broke in on me.

"Leave?" he laughed. "Don't be silly, Brother Ronnie. You're now one of us. You're an apprentice in our lodge, our union."

I frowned. I didn't like the cheer in his voice. I was thinking only of getting to Jo as quickly as possible.

"Which means what?"

"Which means," put in fat Brother Wumpf happily, "that you're to be apprenticed out to our New York branch for training."

"For training," I blurted. "But—"

"You'll have to learn to spook for yourself," Brother Bead reminded me squeakily. "We teach you how. Being a ghost isn't easy, you know."

"And how long," I demanded, thinking of Jo, and that snake in the grass Duane Pearson, "does this apprenticeship last?"

"Three months," Brother Manners said cheerfully.

"Look!" I exploded. And then, carefully, I told them exactly what I thought of the apprenticeship period, and why. "And so," I concluded, "you can't blame me for saying 'excuse me' until I take care of the matter."

Brother Bead looked disapproving.

"Can you use your ghostly powers to their full advantage?" he challenged.

"No," I admitted, "but—"

"Are you thoroughly capable of taking care of yourself in your new status?" Brother Wumpf broke in.

"I don't know," I acknowledged, "but—"

"You're foolish to venture forth without instruction," Brother Manners said. "Why, you don't even know how to use your voice so that humans can hear you."

I had to blink at this.

"Can I learn?" I asked, amazed. Brother Bead smiled, and squeaked:

"Certainly, and plenty more!"

"You know how to lift things, how to physically touch people, or, say, hit them?" Brother Wumpf challenged.

"I never thought of that" I admitted. Proper control of those powers would be a good thing to know, and I could see it.

"Well, then," Brother Manners summed it up. "We'll apprentice you out. You'll learn all these things. Three months won't make that much difference in your plans. In fact, they'll be a help. You'll be thoroughly adjusted by then."

I took a deep breath.

"All right," I said. "I'm game!"

BROTHERS Bead, Manners, and Wumpf had been quite correct.

I had a lot to learn. The next three months, although they

positively flew by, turned me from a bungling amateur into a

first class and quite professional ghost.

I was apprenticed out to a kindly, middle-aged ghost in the Bronx. His name was Brother Watkins, and from him I got my basic training. It seemed that Brother Watkins had a select clientèle of swamies, soothsayers, spiritualists and mystics—who knew about such things—for whom he did most of his work.

I learned how to impersonate voices. How to appear when I wanted to, and disappear when I wanted to. I became an expert at tilting tables and making objects float about rooms. I developed a special, hollow, ghostly voice which I could use when the occasion demanded it.

Now and then Brother Watkins sent me out on house haunting assignments, the first few of which scared the daylights out of me. But I learned to clank chains professionally, and if you don't think this a difficult feat, try it sometime—any time. There is a delicate, rotating wrist motion necessary to make professional clanking.

Brother Watkins knew his stuff. And from him I learned other things. We used to go for walks in the off hours, and in these long strolls he told me endless tales of ghost history and lore, filling up my background on that subject very neatly.

Although I'd been sure that everything seemed far from morbid or unpleasant from the very first hours in which I was a ghost, I learned from Brother Watkins that this new life was not only not bad, but that it was distinctly superior to my previous existence as a human. There was no struggle for existence, for example, because sustaining life was quite unnecessary.

Eating was superficial. But Brother Watkins gave me ghost pills which had all the pleasures of fine meals—from the standpoint of sensation—at any time that I felt a craving for a thick steak or pheasant dressing. Ghost cigarettes were plentiful, and I learned that the lodge had an undiminishing supply of them which it gave freely to any member. Smoking was, incidentally, still as enjoyable as ever.

And, most important of all, ghosts didn't grow old. They stayed just as they were at the time they became ghosts. I, for example, was entitled to perpetual youth.

Boredom, too, was out. For as ghosts we had the opportunity to live beside the world for the duration of its existence—watching it change, struggle, and improve itself. Our task, over and above the mundane jobs of ghosting as humans expected us to, was dedicated to—of all things—"making the world a better place in which to live!"

And there was no gloom, no pall, to hang over as in the case of live human beings. Ghosts are an exceptionally good-natured, easy-going, cheerful lot. The ghost world—I learned—was an utterly blissful one, a real Shangri La.

Personally, I would have been quite blissfully contented with my lot. Certainly I had no envy for the world I'd left behind me. As I say, I'd have been perfectly contented, but for one thing.

Jo was still in my mind.

I told this to Brother Watkins on one of our strolls. He shook his head sympathetically.

"It isn't easy," he agreed. "But those things have a way of working out."

I told him that I hoped he was right. But his only reply was an understanding smile. And as I said, time raced by, and before I knew it, my apprenticeship was up. I was finally ready to go forth to spook for myself.

"I suppose you'll be heading back to Brock City," Brother Watkins said, taking my hand in the lodge grip.

I nodded.

"But I'll be seeing you soon," I insisted.

Brother Watkins smiled.

"There's plenty of time," he replied. "Plenty of time."

I hesitated. Brother Watkins was a good scout.

"Say hello to the boys back in Brock City," Brother Watkins said. "Give them my best."

"I will," I assured him. "I certainly will."

I TOOK a train back to Brock City. That was one of the

things I'd learned from Brother Watkins. Ghosts don't necessarily

have to hitchhike wherever they go. After all, a ghost has as

much privacy on a first class vehicle of transportation as

anywhere else. You'd be surprised at the number of ghosts

traveling the country first class.

Before leaving the depot in the heart of Brock City, I took great pains in primping up and getting ready to look my best for Jo. After all, three months was a long time to be away. She wouldn't see me, of course, although by now I'd learned how to enable her to do so if I wished. The principle of the thing, however, was what counted.

By telephoning a depot taxi stand from a booth a few hundred feet away, I arranged my transportation out to Jo's suburban estate. We use your telephone communications frequently.

In this case I called the nearby taxi stand, told them a cab was wanted at Jo's place. Then I walked over to the stand until I saw the starter give the order to a cabbie. I climbed in, then, and settled back with a cigarette to vision how lovely Jo would look when I arrived.

Brother Watkins had taught me a lot.

After a ride of a little less than an hour, the cab turned up the gravel drive leading to the sprawling manor which belonged jointly to Jo and her Uncle Chester—he's the one who was on the other side of her at my funeral.

It was a distinct treat to see the place again after all those weeks. And when the indignant cab driver argued with the butler, insisting that someone had called for a taxi, I climbed out of the hack and took a leisurely stroll around the familiar old grounds.

Five minutes later, after the taxicab had angrily snarled off down the gravel driveway, I was comfortably seated in the shade of the trees off the tennis court, looking at the carved initials on the trunks—Jo's and mine—and indulging in a lot of pleasant nostalgia.

It was late afternoon, and the sun was going down, giving a little chill to the air. I was making up my mind to get inside and have a look around, when I heard footsteps on the turf behind me. I scrambled quickly to my feet and looked around.

There was Jo!

I TELL you, it was all I could do to keep from making my voice

audible, my appearance visible. Her lovely red hair, her pert

little nose, the cool depths of her beautiful gray eyes—all

were exactly as I remembered them. The eyes weren't quite so

cool, of course, for they were troubled and uncertain.

It was all I could do to keep from putting my arms around her. I stepped back as she moved toward me. She seemed to be walking idly, almost unconsciously. And now I saw that her eyes were moist. She had been crying.

Jo stood beside the tree I'd been sitting under moments before. Her hand reached out and lightly touched the place in the trunk where we'd carved our initials.

"Ronnie," she said softly. "Oh, Ronnie. I hope I'm doing the right thing. They tell me I am, Ronnie. They tell me that it's what you'd want me to do. But I wouldn't, except that nothing matters any more."

I was so choked up inside that I didn't realize I'd moved close to her, almost close enough to put my arms around her. And then an amazing thing happened.

The troubled doubt left her eyes.

"Ronnie," she breathed. "It's—it's just as if you're right beside me. I'd swear you were close enough to put your arms around me."

Frankly, I'm not the superstitious sort, but this made my spine tingle.

And then she turned, in a happy, dazed sort of way, and began to walk back to the sprawling old manor. I had to stand there and let her go, while I tried to drown a few emotions and stop my mind from whirling.

Somehow I felt wildly, joyously happy. Jo still loved me. Jo would always love me!

But suddenly it occurred to me. What had she said? What was all that stuff about what "they" wanted her to do? Something, a ghostly premonition, if you will, made me feel decidedly uneasy all of a sudden.

Just then a large maroon limousine turned up the driveway, and minutes later, as I watched the passengers get out, chattering gaily, and enter the house, I decided that something screwy was certainly going on. And whatever that something was, I'd soon know what it was all about!

WITH the cunning and skill that only Brother Watkins could

have developed in me, I used my ghostly advantages to thoroughly

investigate everything and everybody in the huge, sprawling

manor. I listened to servants conversing. I rummaged through

drawers in Uncle Chester's study. I cut myself in on the

conversation among the recently arrived guests. And this is what

I learned.

Jo was going to marry Duane Pearson!

It took me less than an hour to find this out. And it took me less time than that to find out the "why" of it. Obviously not herself in the months that followed my death, Jo's guidance had been snakily taken over by the thin-nosed Pearson.

He had passed himself off at first as one of my very best friends. Which was a bare-faced fraud. Then, ingratiating himself with her Uncle Chester—who although a likeable old duck was none too bright—the bounder worked his way around to suggesting marriage as the only thing to give Jo a new life.

Jo, poor kid, had protested against this at first. But being in a state of almost constant dazed bewilderment, she'd been literally pushed into agreeing before she knew what was going on. And now, this very evening, as attested by the guests who had already arrived, Jo's Uncle Chester—the blithering ass—was going to announce her engagement to Duane "Stinker" Pearson!

I don't have to tell you what my reactions to this were. I had a first blinding flash of rage in which I decided I would throttle Duane Pearson the moment he arrived at the manor. But then, reason made me discard this, inasmuch as it wouldn't help poor Jo's already distraught state of mind.

I paced back and forth around the house as guests continued to arrive. They were admitted to the lounge, where cocktails were being served, and where Jo and her Uncle Chester received them. It wouldn't do me any good to look at Jo again, I felt badly enough as it was. So I stayed out of the lounge and panthered back and forth over the rest of the house, wrestling with the problem in my mind.

About five o'clock, I hit on an idea—or I should say a series of ideas. And by five-fifteen, I determined that this would be my best and only course. I got Brother Manners on the telephone.

"Look," I said, after talking about three minutes, "have you got all that straight?"

"Certainly, Brother Ronnie," he said heartily. "You can depend on me to come through. Glad to be of help."

"It means everything," I reminded him.

"Count on it," he repeated. "We're happy to help."

I'D LEARNED from the conversation of the servants that the

dinner would begin at seven o'clock, and that the engagement

would be announced at the conclusion of the fourth course.

This would give me sufficient time to build up to the desired climax—I hoped.

After my conversation with Brother Manners, I went back to the door of the lounge and stood there moodily peering in at the guests and listening to the conversation. Jo, as I said before, moved around through all this mechanically, like a person in a bad dream.

But when the butler announced, "Mr. Duane Pearson!" I went into action.

Pearson came strutting up to the door of the lounge like a particularly nasty cat might look just after topping off a dinner of hapless canary. He was wearing evening clothes, and poised dramatically at the door, he touched the corner of the little moustache that hid beneath his long sharp nose. This was his moment of triumph.

Smiling, Pearson stepped over the threshold.

Also smiling, I stuck out my foot, tripped him neatly, and sent him sprawling headlong into the room on his face!

The confusion was immediate, not to mention several hysterical giggles and one or two repressed curses from Pearson himself as two servants helped him to his feet.

I slipped into the lounge as the embarrassment subsided and the conversation resumed again some two minutes later. Pearson, looking like a ruffled peacock, after having paid his respects to Jo and Uncle Chester, had now moved over to chat with some friends.

When I saw the butler bringing a tray of drinks Pearson's way, I moved over beside him and bided my time.

"She's really lovely, and I'm certainly lucky," Pearson said to one of his friends, after taking a glass from the tray.

"Here's to you both," someone said.

Pearson raised his glass. It was a gallant gesture, and would have gone over quite well if I hadn't reached out and tilted the contents down on him just as he'd lifted the cocktail to its peak!

Of course, this led to a great deal more confusion, and resulted in Pearson looking like a drenched duck, or an angry fish. Take your choice. I was beginning to be glad I'd come.

Old Uncle Chester was beginning to fix Pearson with a beady eye, as though trying to decide if the young man had been drinking heavily before his arrival. Other guests were beginning to snicker in his direction.

And Pearson, although still wearing a fixed smile, was beginning to look grim around the corners of his mouth. So far so good.

Of course, when he took another drink from another tray, I managed to have him spill it quite completely over a dowager who sat beside him. This resulted in angry shrieks, much more confusion, and a growing hysterical gleam in Pearson's eyes.

I was working smoothly, and on each occasion I thanked Brother Watkins.

PEARSON, grimly deciding that there would be a certain

safety in being seated, sought an empty chair with his eyes. When

at last he located it, I beat him to it.

This, I must admit, is crude. But he was a sucker for the old pull-the-chair-away-as-they-sit-down gag. And since there was no one to notice it moving just enough, and since no one was within five feet of the chair, Duane Pearson was forced to a lot of apoplectic apologies and explanations after he'd picked himself up from the floor.

The hysteria in his eyes was swiftly approaching the cracking point. I was getting quite pleased with myself, when, unexpectedly, old Uncle Chester rose and announced dinner.

It was an obvious move to get ahead with things before further disaster started. And realizing this, I had to curse. This shot my time schedule all to hell. The time schedule I'd given to Brother Manners. And if Manners were too late—I hated to think of it.

Still crude, but still effective, I worked the chair stunt on Pearson again as they all sat down to dine. There must have been thirty guests to witness his shamefaced confusion as he came up from under the table.

But now I let up for a while, and turned my attention to Jo. A lot was going to depend on her ability to stand shock. It was risky business, and I didn't dare let it miss fire. My psychology had to be good—awfully good.

Jo had watched the various Pearson disasters with a vague blankness that was at once comforting, and disturbing. It was comforting to see that she obviously cared so little for him. But it was disturbing to think of the risk I was going to have to take while she was in such a condition.

I looked at my watch. It was a quarter to seven. I had told Brother Manners to get it here by a quarter after seven at the very latest. But now things were running ahead of my schedule.

Believe it or not, I began to feel cold sweat running down my spine. I tried to keep my eyes away from Jo, and busy myself with heckling Pearson.

Which was a mistake.

I'd just neatly spilled a bowl of soup in Pearson's lap, and he was on his feet howling while the rest of the guests looked on aghast, when old Uncle Chester, sensing that it would be now or never, stood up and began pounding on the side of his glass with his spoon. Pearson who, lips working madly, slumped back into his chair mopping his lap.

Now I knew that I'd again forced the time schedule up a notch. Old Uncle Chester, before the entire affair got out of control, was obviously going to announce the engagement now.

AND it was only seven o'clock! I looked at Jo, and felt

that awful aching tug at my heart. If I'd messed this big

chance—

Old Uncle Chester was clearing his throat.

"Hah, ahhhh, hah, er, hahahhh," he began. "Please, your attention, ladies and gentlemen." He clinked his spoon on the edge of the glass again as if to give himself confidence, and looked doubtfully at Duane Pearson.

"It is my—hah—extreme pleasure, hrrumph, to, ah announce this evening—hah—that my niece, Jo, is betrothed to—hah—hfph," he was off again, clearing his throat a mile a minute.

I wanted to die—if I'd been able to. It was that terrible. Brother Manners, I was now positive, would be too late.

"Kaff," Uncle Chester picked up with words again. "Where was I? Oh—hah, kaff, yes, I recall. To announce the betrothal of my niece, Jo, to—"

And at that instant, while I tried in agony to tear my eyes from Jo's almost pitiful expression of resignation, someone grabbed me from behind, and I wheeled to face Brother Manners.

He was breathless, triumphant.

But before he could open his mouth, I cried. "Gimmme!" and took the box he held in his hands.

I tore the top off the box as I turned back to the table. Tore the top off and took one look at them and knew they were the real McCoy. Then, wildly, I was throwing them up into the air, over the table, watching them drifting down like so much green confetti.

Four leaf clovers—hundreds and hundreds of them!

They were falling everywhere, and to all the guests it was impossible to imagine from where they came. Out of thin air, it must have seemed to them. But not to Jo. I was watching Jo, and she picked up one, examining it curiously. Then her face was shining like a million haloes, and she stood up.

"Ronnie," she said. "You got them, you darling!" And her voice had that small girl squeal of delight in it I'd always loved. She was smiling, radiantly happy at what she knew.

The confusion was frantic.

"Take care of things," I yelled to Brother Manners over my shoulder. "And thanks!" I was after Jo.

He nodded, and took over where I left off, throwing four leaf clovers over everyone—from nowhere. The confusion was now panic.

Jo had a head start on me, and I heard the motor of her little sports roadster starting in the garage. When it came thundering down the gravel roadway, I swung in beside her.

She must have felt my presence.

"Oh, Ronnie," she said. "I'm glad, so glad. I knew you'd come."

I didn't answer. The speedometer needle on the car said seventy, and was going up. I grinned. She was headed for the airport. Jo could fly a ship as well as I could. And she had one there.

"You got the clovers," Jo said. And again there was that small kid joy in her voice. "I knew you would, Ronnie. You're so good about things."

I still didn't answer. I didn't have to.

When we got to the airport, Jo had them roll her ship out on the runway. And I was beside her when we took off. She was still radiant with happiness, her nose wrinkling in the elfin way it did when she grinned.

"You're right beside me, Ronnie," she said when she'd leveled the ship at three thousand. "I know it."

And now, for the first time, I let her hear my voice.

"Sure I am, darling. And I'll always be."

"Oh, Ronnie. You sound so happy. It is happy there, isn't it?" she said. "I can't wait to see you."

She pressed the stick downward, throwing the plane into a nose over. Then she kicked the rudder pedals. We were spinning, and the ground was whirling crazily up to meet us!

"It won't be long before I'm in your arms, darling!" she shouted above the scream of the wind. She was beautiful and laughing. "It won't be any time at all!"

And of course it wasn't—it was merely a matter of seconds....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.