RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

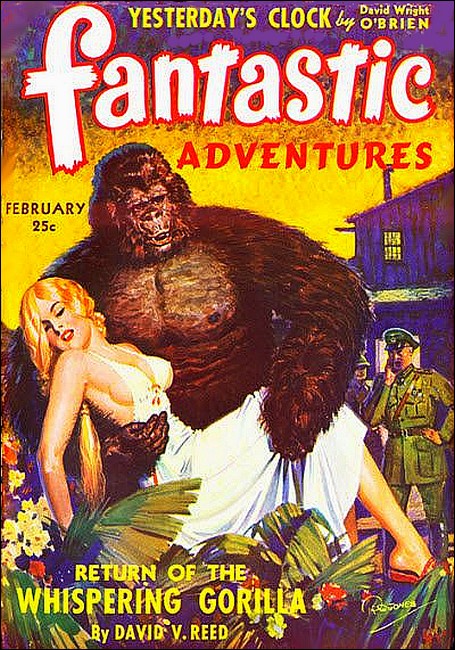

Fantastic Adventures, February 1943, with "Yesterday's Clock"

"The past is gone, mourned Bellows. "It can't be

lived again." The old man looked up. "Ah, but it can...."!

"I'd give my right arm to live this day over again,

knowing what I know now." How often have you said that?!

THE tomato juice tasted foul. The toast was burned and scarcely edible. Someone had undoubtedly done something to the cream, for when it came time to pour it into the coffee, it was slightly sour.

George Bellows endured all this, while wincing his way through the war news in the morning paper. Endured all this and the brisk chatter of Constance, his wife, even though his every instinct told him that this was going to be, but definitely, a bad day.

George Bellows munched his burned toast, took a hasty swallow of his slightly sour coffee, and grimly digested the fact that things looked bleak indeed on the Russian and Egyptian fronts and that the Alaskan situation seemed none too steady.

"And so you see, George," chirped his wife, Connie, with her strange early morning talkativeness, "even though we make a lot of money compared to some of the people we know, we really ought to think of cutting down on our expenses. After all, with this war and everything, we can't be too certain about conditions. Especially since you are in the advertising business, and everybody knows how badly this war has hit the advertising business."

George Bellows looked up at his wife. He sighed despairingly.

"Look, Connie," he began, "how often must I tell you that—"

"You've told me, I know," Connie began. "We'll get down to brass tacks and save pretty soon. But after all, George, when you consider the fact that there's a war on, and—"

George Bellows cut in on his wife a trifle sharply.

"I am quite aware of the fact that there is a war going on," he said. "But after all, Connie. We ran up a lot of bills, somewhat necessary bills before December eighth. We still have them to clear up before we can honestly begin to save for ourselves. Besides, we're doing quite well. You aren't without clothes—" he looked at his wife's comfortable though sloppy negligee and added, "literally. And we aren't starving. Don't fret so about things. There's enough to worry about these days without additionally straining yourself!"

Connie Bellows, an attractive, well-meaning, though scarcely economical wife, looked injured. She threw back her pretty blonde head indignantly and sniffed.

"I was just trying to be helpful," she declared tartly.

George Bellows laid the paper down very carefully. He was a dark, bronzed, masculinely handsome chap in his late thirties. He had eyebrows which were capable of registering infinite sarcasm. Now they did so.

"You really do try very hard, my dear," he acknowledged frostily. "It's such a pity that your best is none too good."

Connie Bellows looked at her husband, George, open-mouthed in shock and flushed anger.

"Is that so?" she demanded in rising accents.

George Bellows picked up his newspaper.

"I am afraid it is," he said. He turned to a perusal of the grim Russian situation.

Connie Bellows rose, planking down her coffee cup indignantly. Her gray-green eyes were sparking danger.

"You—you," she struggled, "you unappreciative beast!"

SHE turned and left the room wrathfully. George Bellows heard her mules clicking as she ascended the stairs to the bedroom, but his eyes returned to the paper. Connie was a nice kid, a cute trick, a fine wife. But she was an impossibly bungling, though eager, financial manager. George Bellows had never minded this fact. But he did mind her occasional outbursts of economy in which she tried to pin all the blame on him for their not having any reserve capital.

"Have dinner ready at six-fifteen!" he called after her callously. "I'll be home then."

There were days when George Bellows, on having thus wounded his well-meaning wife, would follow her to the bedroom and console the inevitable tears that followed such a battle. But this was not one of them. This was a day in which he drank foul tomato juice and munched burned toast between swills of sour coffee.

This was a bad day.

George Bellows contemplated his problems, sandwiching them in, so to speak, between the infinitely more important issues facing him from the black type in his morning paper.

As Connie had stated, the advertising business, of which George was a part, was none too solid these days. What was there left to advertise? Too, although his job as a copywriter in a fairly secure agency paid him rather well, George Bellows—always easy-going and seeking a good time from life—had never bothered to insist that Connie build up a nest-egg against some calamity.

The war had caught the Bellows flat-footed. Like innumerable other persons they had not expected it—at least so soon. They had arranged their living schedule quite along business-as-usual standards and had even been so unfortunate as to indulge in a buying spree for things for the house shortly before the United States became involved in the grim conflict.

Thus it was that this rosy summer morning found the Bellows in the position at which Connie had somewhat vaguely hinted. George Bellows had a good job in a shaky business. But the Bellows' finances weren't cached in banks, due to bills still pending. And the only money on which they could count at present was the rather comfortable stipend he received from week to week.

It was not an impossible situation, however. There seemed no likelihood of George Bellows losing his job. And once the bills were cleared up, saving would be a simple thing—if kept out of Connie's hands.

And so it was that this rather crystal clear picture of the situation, plus the burned toast, the sour coffee and the foul tomato juice, made George Bellows a trifle irritated that morning.

It might have been his morbid interest in the bad tidings from Moscow, or merely his defiance of his wife's gloom casting, which kept George Bellows a bit longer than usual over breakfast that morning.

AT any rate, when he finally looked up from his paper—some fifteen minutes after Connie had stamped upstairs—he realized with a start that it was almost twenty minutes till nine o'clock.

George was due at the advertising firm of Barton and Biddle at precisely nine. For that was where he was employed.

Hastily he rose, starting wildly for the living room, where Connie had undoubtedly left his hat somewhere out of reach.

Being late to work, before the war and the grim result on the advertising business had taken over, had never bothered George Bellows. As a talented and much-needed copywriter in Barton and Biddle he'd more or less grown used to getting to the office anywhere around ten. But that had been before December eighth and the death knell it rang in George's business. Now things were different, and George hopped for his job like a copy cub.

Cursing, Bellows finally found his hat. And when he'd piloted his car from the garage, he swung around the next corner on two wheels and roared recklessly into the rather thick stream of Sheridan Road traffic headed loop-ward.

It generally took half an hour for George Bellows to get from his north-side home to his Michigan Boulevard office. And now he was faced with making the journey in—he looked at the clock on the dashboard—but half that time.

Consequently, he took a few chances in his dash toward Chicago's loop that morning. He did a considerable bit of weaving which motorcycle policemen would have frowned upon. But he made time, and reached Foster Avenue where it joined the Outer Drive after but seven minutes driving. Reached Foster, and started to turn left, only to find that the Outer Drive—due to construction going on—had been blocked off.

"DETOUR!" said the sign, and so George Bellows and the rest of the motorists in the stream of traffic were forced to comply. Forced to comply at considerable sacrifice to speed.

George Bellows cursed most fluently as he followed the definitely retarded traffic along the usual Sheridan Road run toward Lincoln Park.

"I'd have made it," he told himself. "Dammit to hell, I'd have made it—if it weren't for this detour!"

The red-lights were especially irritating to Bellows, who was all too well aware that he would have encountered no such hindrances had the Outer Drive been open. He followed Sheridan Road's leisurely winding route with increasing impatience.

Then at Sheridan and Broadway, Bellows once again encountered the grim sign, "DETOUR!" It meant that he would have to follow the cobble-stoned pathway of Broadway, this time.

The profanity of George Bellows was, at this juncture, the devil's own poetry. Broadway was infested with rocking, lumbering streetcars, which were a nightmare to any motorist, a headache to any unfortunate streetcar passenger.

And now it was jammed with traffic usually destined for Sheridan Road or the Outer Drive, plus its regular stream.

As George Bellows shifted gears from first to second again and again, laboriously making his way along this clogged, extraordinarily sluggish street, he had gruesome mental visions of the expression of Homer Barton, his boss.

"Late, eh, Bellows?" George could hear Barton's nasal intonations.

"Late, eh?"

The implications of that phrase were enough to send Bellows into a cold sweat. "Late, eh?" could mean anything from, "Watch your job in these times of stress," to, "Draw a month's pay in advance," in the present scheme of the agency's attitude.

And it was over just that phrase that Bellows was shivering when the red, stop-light just ahead of him at the intersection was advertised in advance by a yellow light.

UNDOUBTEDLY the worry of George Bellows was one of the causes which made him jam his foot hard on the accelerator when he saw the slow-light flashing from the post at the intersection. He had been worrying about his being late, and acted instinctively when he saw the sign of something that would hold him up even longer. And as he jammed down hard on the accelerator, his automobile shot recklessly across the intersection just as the post at its corner turned from warning yellow to definite-stop red.

George Bellows' automobile hit the precise center of the intersection at the same instant as a heavy beer truck traveling at an exact ninety degree angle. The collision of both vehicles was more or less inevitable.

The crashing tumult of the accident was still roaring in Bellows' ears when his car slid screechingly to a stop at the curbing of the intersection. He knew, without looking around, that the accident had caused considerable damage, none of which had been suffered by the monstrous beer truck.

And then, mechanically, Bellows was climbing out of his car, the screeching of automobile horns and the shouting of spectators loud in his ears.

One glance at his machine showed Bellows all too clearly that the entire rear of it had been pleated in almost accordion fashion. Pleated so thoroughly that it seemed unlikely it would ever be of use again.

A sudden sick nausea gripped George Bellows. Where in the hell could he ever get another car now that the war was on?

The driver of the beer truck—which had apparently suffered but minor damages on the bumper—had climbed down from his roost high above its huge hood.

He was a round, squat little man of much girt and sinew. He had a shaven head and small, piggish, angry eyes. He advanced on George Bellows, spurred, perhaps, by the spectators surrounding the scene.

"Okay, buddy," snarled the driver of the beer truck quite belligerently, "whatta yuh gotta say fer yuhself?"

Suddenly the pent-up emotions of George Bellows flowed forth. There had been the tomato juice, the burned toast, the sour coffee, Connie's economy prattlings—and now the loss of the last decent car he'd be able to get his hands on.

George Bellows strode swiftly toward the pig-eyed driver of the beer truck, not thinking in terms of the girth and sinew of the chap.

"You bald-pated blockhead!" George Bellows yelled. "Who do you think you're snarling at? Why didn't you look where—"

That was as far as George Bellows got.

THIS hot outburst was cut sharply and efficiently by the sudden presence of the bald-pated blockhead directly in front of him, and the swinging of said blockhead's hard right fist.

The punch caught Bellows on the mouth.

It made his head ring and his knees crumple. It landed him flat on his back in the middle of the cobblestoned street, with a mouth full of blood and horribly unfirm teeth.

The spectators screamed approval which came but dimly to George Bellows' ears.

Groggily, Bellows was trying to climb to his feet. He almost succeeded until another chopping right hand came out of the fog to smash with an agonizing crunch against the side of his jaw. George Bellows sat down hard in the cobblestoned street once more. And again, but more dimly this time, there came to his ears the hoots of a crowd.

This time instinct kept Bellows from trying to rise. And the intervention of instinct, plus a sudden dreadful nausea, held him where he was until a voice apart from the hooting crowd broke through the fog.

"Come on, get up wit yez!"

George Bellows blinked dazedly and realized that a red-faced person in a blue uniform was bending close to him and glowering with a great deal of belligerence.

Sickly, aware this time that he had the help of Law and Order, George Bellows endeavored to rise. The first effort failed, but the second, thanks to two beefy paws under his arms, succeeded.

He stood there swaying, holding his mouth with one hand and his splitting skull with the other. The hooting crowd had silenced almost entirely, as all ears strained to catch his first words.

"What do yez mean driving whilst dhrunk?" demanded the man in the blue uniform. He was a policeman.

"I'm not drunk," Bellows muttered thickly between puffed lips.

"Then why are yez running through the red-light, and why are yez insulting this upstanding driver of the beer truck?" demanded the red face and big mouth of the policeman.

"The light was yellow, not red," Bellows mumbled, hand still over his bleeding mouth. "And I didn't insult this beer truck driver. I was—"

"Niver mind what yez was!" snapped the policeman. "Yez should feel grateful yez didn't kill any young childrun with yer reckless drunken driving!"

"I'm not drunk!" groaned Bellows. He still didn't dare remove his hand from his mouth.

The officer turned from Bellows to the obviously delighted driver of the beer truck.

"Do yez have this fella's number?" the policeman demanded.

"Sure," said the driver; "the louse!"

Horns began to hoot impatiently in the line of cars delayed by the accident. The policeman glared over his shoulder at them. He turned back to the beer truck driver.

"Yez'd better move on," he advised. "I'll handle this dhrunken minice to little kiddies."

The driver went regretfully back to his beer truck. George Bellows found a handkerchief with which he began to wipe the blood from the corners of his swollen mouth.

"I oughtta run yez in fer reckless driving," said the policeman belligerently. "But yez seem to have had yer lesson in the loss of yer machine and the desarving clout on the mouth. Now git that junk offa the corner!"

BELLOWS watched the policeman turn away and stride to the center of the snarled traffic. Sickly, Bellows staggered back to the wreck of his machine. He climbed in behind the wheel and tried to start the motor. There was no result.

Bellows was climbing out of the machine when the squad car from the Accident Detail arrived with sirens wailing. Two uniformed policemen spilled out of the squad and came directly over to Bellows.

"You own this wreck?" one asked.

Bellows nodded.

The uniformed copper produced an accident report book and pencil.

"Look, officers," Bellows implored, "I'll call in, or come to your station tonight with a full report. I'll have a tow truck pick up my car. But I'm late for work already, and I have to rush."

The officer with the notebook glared at Bellows.

"Not so fast, buddy," he snapped. "You aren't going nowhere until we get this report made out."

"But—" Bellows began.

"Hold your pants on, buddy," the second copper said. "This isn't gonna take long. Besides, if your boss is sore, you'll have a good excuse."

"Very well," Bellows sighed despairingly....

THE accident took better than fifteen minutes to fill out. Fifteen minutes added to the ten minutes consumed by the accident itself and the one-sided battle with the truck driver added up to twenty-five minutes all told.

It was precisely twenty minutes after nine when George Bellows left his smashed car and the scene of the accident and started for his office by cab.

Another ten minutes went by before he arrived at his office. And when he stepped into the big front bullpen of the Barton and Biddle Advertising Agency, it was some two minutes after nine-thirty.

Bellows nodded to the switchboard girl and other assorted stenographic help as he made his way through the bullpen to his own private office.

He had his hand on the door of his office, when he heard the voice of Homer Barton, his boss, directly behind him. A cold, quiet, precise voice.

The voice said exactly what Bellows had expected it to.

"Late, eh, Bellows?"

George Bellows, flushing, turned to face his boss. A half hush had settled over the bullpen as the stenographic department bent all ears to hear the star copywriter get told off.

"Yes," George Bellows said. "Yes, Mr. Barton, I'm afraid I am. I had a little—"

That was as far as Bellows got. Homer Barton grabbed the ball and ran the conversation out to a touchdown from there on.

"Bellows, this office has no place for tardiness or negligence with business as bad as it is these days," Homer Barton snapped. "It is the duty of every employee of this agency—no matter how important he may feel he is—to be more than on his toes in such trying times.... Arriving to work in such a leisurely fashion as this tends to disrupt the morale of the entire working force here. I find it hard to countenance, Bellows. You are not so important around here that you can—"

At this point George Bellows, acutely conscious of the fact that he was getting this tongue lashing in front of the entire office staff, cut in crimsonly on his employer.

"If you would let me tell you what happened—" Bellows began.

"What happened is of no immediate concern, Bellows. Possibly you overslept. Possibly you just didn't feel like getting down until now. In any event—"

And at that instant George Bellows blew his top. Everything that had happened to make this a definitely bad day, from the moment of the first sip of foul tomato juice until this present humiliation, exploded into red rage.

"Damn you, Barton!" Bellows shouted. "Shut up before I push your fat little face in for you!"

There was an immediate shocked silence throughout the office. Homer Barton, eyes bugging, pink cheeks growing white, stared aghast at Bellows for an instant. Then his thin lips went tight in white satisfaction.

"Draw your pay, Bellows," he said icily. "You can have the usual month in advance allowance, also. Then please get out of this office for good."

George Bellows glared at his boss for an instant, the red rage still with him. He clenched and unclenched his fists, then decided hitting that smug face of Barton's wouldn't help any. He turned on his heel.

"That's quite all right with me, Barton," Bellows grated....

HALF an hour later, George Bellows sat at his favorite, near-the-office bar. He was minus one automobile, one boss, and one job. Bitterness and sick apprehension and brandy filled him with a sort of numbed buzz.

In his pocket Bellows had eight hundred dollars. A month's dismissal pay in advance, plus the two week check that had been due that day.

"Give me," Bellows told Mindy, the bartender, "another brandy and soda."

Mindy went to prepare the drink, and Bellows returned to his gloomy contemplations. For the twenty-first time he told himself that this was it. This was the dire calamity about which Connie had babbled at breakfast this morning. No job, and nothing to his name but the money in his pocket. Just enough money to carry them along for a little better than a month in the style to which they'd adjusted their living.

Bellows was a good copywriter. A fine copywriter. But advertising was shot to pieces, and agencies were just hanging on to the men they had. They weren't hiring new writers. Sickly, Bellows realized this.

Of course there were newspapers. He could get a newspaper job. But it wouldn't pay him as well as the one he'd had, and besides, he hated to think of pounding police beats for fiendish city editors.

Mindy brought Bellows his drink, and he downed half of it in his first gulp.

How, he wondered grimly, was he going to break the news to Connie? How especially, after their exchange of that very morning? Bellows pushed this unpleasant problem from his mind and went back to wishing that he were any kind of a writer other than an advertising copywriter. The advertising writers were the only ones who were having a grim time of all this. News writers, magazine writers, screen hacks, all of them were doing nicely. But he, George Bellows, had to be an advertising writer. He hated the word advertising for a moment. Then he hated himself.

It was at this moment that Louie the horse-bookmaker came into Mindy's.

LOUIE was a thin, dark, dapper little man who spoke with a New York accent and always wore a boutonnière. Today it was a white carnation. He took the bar stool next to Bellows.

"Hello, Georgie," Louie said affably. "Yuh look as though yuh lost yuh dawg."

Bellows studied his drink. "Maybe I did," he acknowledged. Then he added. "How's your business. Taking the suckers down the line as usual?"

Louie laughed politely at this. "Yeah, sure thing. You know me. The oney honest bookmakah in the business, Georgie. They bet the bangtails; I pay off. I don't make 'em pick no wrong nags."

Bellows finished his drink, clamped it hard on the bar and beckoned to Mindy for another. He turned to face Louie.

"Got a race sheet handy, Louie?" Bellows asked.

Louie beamed. "Sure thing." The race sheet came out of the bookmaker's pocket with magical speed. Bellows took it.

"I want to look at Arlington," he said.

Louie waited with bland patience as Bellows studied the lists of the horses and the races. It took a little time, but finally Bellows looked up from the sheet.

"I've had the devil's own bad luck this morning, Louie," he said just a trifle thickly. "In fact, I've had such bad luck that no man could have anymore. That's why I figure the law of compensh—compensations will help me clean you today. I'm bound to clean you out."

"Glad to have yuh try," Louie smirked.

Bellows nodded solemnly. "That's just whash—what I'm going to do." He reached into his coat pocket for his billfold.

Louie looked around with sudden apprehension.

"Come on ovah in the corner," he invited. "We don't wantah place no bets in fronta the woild."

Bellows clambered from the stool, and billfold in hand, followed dapper little Louie to a corner of the bar.

Louie brought out a ticket sheaf, held a pencil ready.

"What nags you want?" he asked.

"Only one," said Bellows. "Despair, in the first. It's listed at fifteen to one. What's your price?"

Louie's sharp eyes glittered. "I kin oney pay ten to one, Georgie. I can't give no track odds, you know that."

Bellows shrugged. "Okay, okay. I ought to know thash—that by now." He opened his billfold. "How much can you cover?"

Louie blinked at the display of greenery. He moistened his lips with his lizard-like tongue.

"I kin covah anythin from one to a thousant; you know that Georgie," he said.

"Okay," Bellows said recklessly. "I want to put seven hundred on Despair."

The little bookmaker's eyes almost fell out. But he scribbled rapidly on a ticket, pocketed a duplicate, and handed the ticket to Bellows.

"Seven hundid smackahs," Louie said. "Hand ovah, Georgie."

Peering slightly through blurring vision, Bellows extracted seven hundred dollars and handed it over to the bookmaker.

"Despaih is your nag, Georgie," Louie said. "You gotcha ticket. Ten to one."

"So you'll owe me seven thousand dollars when the first race at Arlington is over," Bellows declared, pocketing his ticket.

Louie nodded, just a trifle pale.

"Yeah, Georgie, heh, heh. You'll rilly break me if Despaih comes through."

"With the luck I've had," prophesied Bellows, "I can't lose. Better go to your bank, Louie, and get ready."

Whether or not Louie went to his bank Bellows didn't know. But the little bookmaker left with the seven hundred dollars a few minutes later, and Bellows returned to the bar to order some more brandy and soda.

IT WASN'T until an hour later that Bellows began to feel, even through the alcoholic haze, that his bet might not have been the wisest thing in the

world under the circumstances. And on trying to think back over the sudden unhappy impulse that had been its cause, Bellows began to wonder exactly what in the hell ever prompted him to do such an asinine thing.

Worry has a faculty for serving as a sobering influence. And Bellows' worry about the horse bet which represented seven-eighths of all the capital he had left in the world, soon began to negate the effects to the brandy.

By noon, he was suffering the torments of the damned, and with frantic despair was trying to rationalize himself into a fatalistic frame of mind in order to shrug off his woes.

But it wasn't a successful effort. At twelve-thirty, Bellows beckoned to Mindy the bartender.

"Where's Louie the bookmaker?" he asked.

Mindy went on polishing a glass. "I dunno, George, why?"

"I want to find him, that's why," Bellows said. His voice was a little shaky.

Mindy shrugged. "He's all over, picking up bets and the like. He's generally back in here in the afternoon, though."

"About what time?"

"About three, four o'clock."

Bellows winced inwardly. The race in which Despair was to run, the race on which he had wagered seven hundred bucks, was run before two. If he were going to find Louie and cancel that bet, he'd better get moving. He rose from his stool none too steadily.

"Where do you think there'd be a good chance of finding him?" Bellows demanded.

"Who?"

"Louie," Bellows said impatiently.

Mindy thought a moment. "You might try the corner of Clark and Randolph. He generally picks up a lotta politicians' bets in fronta the city hall there."

Bellows nodded a brief thanks and left. He caught a cab and told the driver to go to Randolph and Clark. It took ten minutes. But Bellows didn't find dapper Louie on any of the four corners. He wasn't around the city hall, either.

Bellows decided to fight off his mental panic with a drink. He went into the first tavern he found. One drink, quite naturally, led to four more. Immediately after that he stepped into the street again with the very fuzziest of notions as to tracking down Louie. He didn't get any farther than the next tavern.

BELLOWS realized in horror, some half hour and three drinks later, that it was almost time for the race at Arlington. The race on which he'd placed what practically amounted to his soul. The realization came to him through the simple medium of the radio behind the bar, and the announcer's voice that said:

"Well here We are at Arlington, waiting for the starting of the first race."

Bellows looked up from his brandy at the sound of that cheery sports-caster's voice, and his nausea and panic returned.

"The horses are coming out onto the track now," said the announcer, "moving down toward the big starting gate. The crowd is buzzing with excitement as it waits for the opening of today's racing."

"Oh God," thought George Bellows. "Oh God."

"Number one post position is held by Despair," said the announcer. "That horse is ridden by jockey Stan Hemp, and listed at fifteen to one starting price."

There was more from the cheery race-side sportscaster, more which was lost in a cloud of sick, bitter remorse as far as George Bellows was concerned.

Dimly, the account of the difficulty entailed in getting all the horses into the starting gates came to Bellows' ears. Dimly, too, the sudden cry:

"They're off!"

Bellows buried his nose deep in his glass, almost as if he were trying to cover his ears with it also. But the announcer's voice came through to his consciousness in spite of this.

"It's Despair, breaking fast," said the announcer. "Despair taking the lead as the horses thunder around the first turn!"

A curious expression came into George Bellows' eyes; he lifted his head from his glass. Something in his stomach was suddenly twice as terrible as the grief he'd felt moments before. It was a pathetic, anguished, dare-I-hope feeling which tore him apart.

"Now in the backstretch," the announcers' voice came through again. "Despair still holds the lead, by three lengths. Coming up fast on the inside, however, is Castaway, the favorite."

Bellows gripped the edge of the bar with his fingers until the knuckles were white. He closed his eyes.

"Despair still in front, only by a length now, as the horses came into the last turn. Castaway still inching up; another horse, on the outside, making a game bid. Other horse is Merrily. And now they're in the stretch, beating down for the finish line!"

George Bellows lived and died a thousand times in the next fifteen seconds. The announcers' voice was now the all consuming focus of every last atom of Bellows' will power, nerve fiber, very being.

"Despair still by half a length. Castaway fading back. Merrily, the twenty-to-one shot, moving up to within a quarter of a length of Despair. They're nearing the finish line and it's—Merrily? Yes, Merrily wins by a nose in a tremendous last stretch drive! Second was Despair, third was Castaway. And that's the end of the first race at Arlington Park, run at—"

But George Bellows wasn't listening any more. He'd slid from the bar stool and started blindly toward the door. Like a thumping carnival drum in his brain there came the chant: "Seven hundred bucks. Seven hundred hard earned dollars. Down the drain. Down the drain. Nothing left. Nothing left. Down the drain."

He stopped just outside the tavern door and pulled out his billfold. Carefully, groggily, he counted the money he had left. A little over eighty bucks. George Bellows wondered just how damned drunk a fool could get on eighty bucks.

He decided to see....

IT WAS scarcely three hours later when George Bellows, having found a bar, tropical in atmosphere, on the near north side which specialized in zombies, rolled forth for said south sea-ish bistro on his ear.

Taken under the most rigidly equal of circumstances, zombies are not drinks to sneer at. And taken with the quantity of brandy which had already been consumed by Bellows during his disastrous day, their effect can be most mildly described as sledge-hammerish.

George Bellows, through much coy maneuvering, had managed to down six zombies, even though that bistro had a strict limit of two to a customer. With the tactical brilliance given only to drunks and idiots, Bellows had discovered that since the bistro had two distinct bars and another room distinct from both bars, he could go to both bars and to the third room and have two zombies in each. That he did.

And at his third bar, Bellows found a fast chum. A dark, bearded little man with a long, pointed nose and sharp dancing eyes. The little chum called himself Achmet, which name Bellows freely translated into Allah before their acquaintance was ten minutes old.

In the dark, bearded, politely attentive Achmet, Bellows found the delight of all woe-ridden drunks, a sympathetic audience.

To little Achmet, Bellows related the entire happenings of his undeniably tragic day. And again and again Bellows demanded, with gestures, that Achmet explain the workings of fate against George Bellows.

"Ish not fair, Allah," Bellows protested. "Ish jush like a damn chain tied roun'm' neck by Fate!"

"Fate," said little Achmet quietly, "has a way of being quite unconquerable. One cannot run against its winds, my friend."

This, quite naturally, served to bring out any latent perverseness in the fogged mind of Bellows. He decided to argue the point.

"Thash not so!" he protested. "All's I hadda do today wash to change a few thinghs I did, 'n' everything wouldda been different. I couldda changed it all, if Idda known, and Fate couldn't do a damn thingh aboush it!"

At this little Achmet raised his jet black eyebrows.

"You think so?" he asked with a queer little smile.

Bellows nodded, drunkenly emphatic.

"CourshIcould!"

"Supposing," mused little Achmet, "you had all of today to live over. Do you think you could avert the trouble you've had?"

Bellows pounded his fist on the bar. "Ubetcha!"

Achmet appeared to change the subject suddenly. "Do you have any interest in clocks, my friend?"

"Wha kina clocks?" Bellows demanded.

"Unusual clocks," the little Achmet said. "Clocks with strange powers over their servant, time."

"Sure," Bellows lied with drunken cheerfulness and a casual wave of his hand. "I'm the orishinal clock bug. I'm inereshted in everything outta th'way. Where'sh thish clock?"

MUCH to Bellows' amazement, the little man reached into his pocket and brought forth a small, curiously designed timepiece not larger than the average pocket watch. It seemed to be encased in a coral substance, and was topped by tiny, delicately carved camels. Its face seemed much like the face of an ordinary watch except that it was sectioned into three circular parts, each of which had watch hands and numerals.

Achmet handed the strange little clock to Bellows.

"What do you think of it, friend?"

"Ish really 'stonushing," Bellows exclaimed. "Whash the three sets of hansh for?"

Achmet smiled, as though he'd expected that question. "One set tells the time today," he said. "The other tells the time tomorrow, and the third tells the time yesterday."

"How ver, ver cleversh!" marvelled Bellows.

"It is the third section that should intrigue you, my friend," said Achmet.

Bellows blinked. "How'sh thash?"

"It tells the time yesterday. When it is set to run for yesterday, it will transport its bearer back twenty-four hours into the preceding day. In other words, should you wish to try to conquer this woeful day by living it all over again, all I would need do would be to set that third section going and give you the watch."

Achmet's eyes twinkled as he looked up at Bellows.

"Inereshing," Bellows mumbled.

"Yes," little Achmet agreed. "Especially in view of the fact that that is precisely what I intend to do. I will set the little clock"—he took it from Bellows' hand—"for the yesterday section." He peered down at the timepiece, holding it in one hand while his slim, amazingly dextrous fingers tinkered with the third section on its face. Then he started winding the stem gently. He smiled, and handed the watch to Bellows.

"There, my friend. I have set the watch and now it is yours. Precisely at midnight tonight, you will be sent back into yesterday. Yesterday will, of course, be this day, the day you wish to live over again."

Bellows blinked foggily at the watch.

"Don' get it," he mumbled.

"You will comprehend as soon as the phenomenon occurs," Achmet assured him. "Even though befogged temporarily, you will recall all this when you begin this day over again. You are given your wish to relive this day. I, Achmet, wish you luck in your struggle against the fates."

Bellows was still staring uncomprehendingly at the little clock.

"Thanksh," he muttered.

"Now, if you will excuse me," said Achmet.

"Sure, sure," Bellows mumbled. "Ish jush downstairsh onna right landing." He watched Achmet leave, smiled when the little man turned at the door and smiled goodbye. Then Bellows held the watch to his ear, shook it, shook his head, and pocketed it.

"'Nother zhombie, pleash!" Bellows told the bartender.

The bartender smiled regretfully. "Sorry, sir. You've had the limit of two."

Bellows sighed resignedly and turned away from the bar. It suddenly occurred to him that he'd best look in at his house. The way things had gone this day, he wouldn't be surprised to find it in ashes on his arrival.

It never occurred to him that he was riotously drunk. And it never occurred to him that he had Connie to face in that condition. He found a cab outside the south sea-ish bistro, gave the driver his address.

"And hurry, shee," Bellows demanded. "The plash'sh burning down!"

He sighed and leaned back on the cushions....

CONNIE was waiting for George Bellows as he stumbled up the porch steps searching for his key. The taxi had just roared off, and Bellows was bent over on hands and knees retrieving his billfold, key case and cigarettes when his spouse opened the door.

From the arctic tones of her voice it was obvious that she had watched his uncertain navigation up the walk to the house.

"Well!" Connie said acidly. "Pick up your things, drunken bum, and come inside. You'll find it eighty degrees cooler in here, I'm sure!"

George Bellows blinked at his wife, picked up the last of his scattered effects, and got up waveringly from his hands and knees. He essayed a smile.

"Lo, Connie. Look lovely!"

"Get in here!" his spouse ordered.

Bellows weaved into his home, and Connie slammed the door behind him.

"What is the meaning of all this, you snake?" she demanded. And then, before he could answer, she added suspiciously: "Where's the car?"

George Bellows smiled vaguely at his wife.

"Smashed the damn thing up. Didn' like it, anyway. Ran ish shmack inna trucksh!"

"You ran it into a truck?" Connie's eyes were wide, her voice horrified.

George Bellows nodded a trifle proudly. "Never ush car again. All shmash."

"Oh, George!" His wife's voice was a wail of anger and pain.

"Accomplish lotta thingsh today." Bellows weaved there smilingly as he spoke. "Tole Homer Barshun whash he could do wish the damn job. Quit coldsh."

This was not a precise recounting of what had happened. But to Bellows' fogged mind it seemed like an excellently brief manner of imparting everything to Connie without too much wasted words and explanation.

"George!" Connie gurgled the word in shocked, sick fear.

Bellows nodded, still smiling with vague happiness. "Put alia money I collectsh from Barton onna horsh. Horsh almosh won. Ran secun."

"How," Connie managed sickly, "how much money did you put on this—this horse?"

"Sheven hunner dollarsh!" said Bellows with shy pride.

There was a moment of unbroken, electric silence. His wife stared at Bellows utterly aghast, as if she were viewing Bluebeard in Madame Tussaud's wax museum for the first time. Her face was white, and twin crimson splashes of rage marked her cheeks. Her pretty lips were a tight line of frigid wrath.

Her voice was scarcely a whisper when she finally spoke.

"I'll send someone over tomorrow for my things," Connie said. "I couldn't stand staying in this house another minute. If you ever see me again, it'll be because you scraped up train fare to appear in person at Reno!"

She stepped around him, then, opened the hall door and slammed it shatteringly behind her as she left the house.

GEORGE BELLOWS looked sickly at the still trembling door. He turned and staggered into the living room. As tight as he was, he knew that this was the payoff. This was the final crushing blow of the hideous day.

He suddenly felt very sick, terribly weary, and dreadfully drunk. He peeled off his coat, letting it drop to the floor. Then he bent over, picked out a small object from the pocket of the coat and stared curiously at it.

It was an exceptionally strange little clock of some sort. Drunkenly, Bellows swayed there unsteadily, staring down at the curio. He held it to his ear, then shook his head. There was no recognition, no recollection in his eyes as he stared at the clock. He lurched over to a coffee table and placed the curious timepiece carefully atop it.

Then he slumped soddenly down on the divan. He started to lean back. He felt as if someone were trying to close his eyes. He sat up, fighting off a swift nausea.

Carefully, Bellows bent over and removed his shoes. This done, he leaned back on the divan again, and again it lured him hypnotically. He felt so tired. So damned tired. He sank back wearily.

Minutes later his snores resounded through the room. He was asleep, or, more precisely, was "out cold."

STRONG morning sunlight, pouring into the face of George Bellows, finally succeeded in waking him scarcely two minutes before the alarm clock went off.

For a moment Bellows lay there, blinking appreciatively in the warming glow of nature's klieg lights. Then, suddenly, he sat up in bed and looked wildly around.

In the twin bed beside his own, Connie, his wife, slept peacefully.

Bellows put both hands to his head, closing his eyes. Then he opened them again. Connie was still there. The morning was still sunny, and he was still in his bedroom.

"My God," Bellows gasped. "How did I get here?"

The memory of everything that had occurred in the preceding twenty-four dismal hours returned to him in an overwhelming flood of remorse and sick anguish.

His car smashed, job gone, money lost, wife walking out on him. His sick drunk and his passing out downstairs, all that came to his consciousness.

"But Connie isn't gone," he told himself perplexedly. "She's right here, and I'm in bed, not sprawled on the couch downstairs. I don't even have a hangover. What's it all about? Could it have been a dream?"

He closed his eyes trying to reason it out. He'd be sick as a dog if he had been drunk the night before. But he felt fine. Connie wouldn't have returned in a hundred years, had she walked out on him. Yet here she was right across from him.

"It couldn't have happened," Bellows told himself.

And yet he could swear that it all had happened. But how could he argue against the facts of the present situation, facts belying all the vividly terrible recollections he had?

"My God," Bellows muttered, "it must have been some terrible dream!"

Then he saw the clock, and knowing that the alarm was due to ring in another instant, he reached over and shut it off. Quietly, then, Bellows rose and slipped into a bathrobe.

For a moment he stood there beside his wife's bed, frowning. That dream, that damned nightmarish dream, was still as clear to him as if he'd actually experienced it.

"I'd be willing to swear it all happened," he thought. "I'd swear to it on a mountain of Bibles. Ugh!" He shuddered at the grim recollections that were still with him.

George Bellows then woke his wife.

Connie blinked sleepily, opened her eyes fully, then smiled at her husband.

"Good morning, George. Time to get up already?"

Bellows smiled none too certainly, for the vivid recollections were still persistently with him, and he told her it was almost eight o'clock.

"I'd better hurry with your breakfast then," Connie said. "You start dressing and shaving and I'll have breakfast ready by the time you're done."

Bellows nodded, still bewilderedly unconvinced about everything, and started for his morning shower....

WHEN he came down to breakfast, the puzzled expression was still in Bellows' eyes, and he gazed at the table warily. It was set for him as usual, tomato juice, coffee, toast, a newspaper propped up against the sugar bowl.

Connie came out from the kitchen, smiling brightly.

"You seem strange this morning, George. Anything wrong?"

"No," Bellows said, seating himself.

"No, nothing at all."

Connie took a seat across from him.

"That's good," she declared. Then she began to chatter brightly about innumerable inconsequential things, while Bellows picked up his tomato juice and glanced down at the headlines in the paper.

He had two shocks simultaneously.

The tomato juice tasted foul, and the headline in the paper was the same as he had seen it in his, his "dream!"

Connie, still chattering happily, didn't notice her husband put down the tomato juice hastily and stare in pop-eyed amazement at the paper.

With a hand that trembled visibly, Bellows lifted the lid from the toast tray and looked beneath it. The toast was burned!

It was all he could do to reach for the cream pitcher and gingerly pour a little of the liquid into his coffee. Then after adding sugar, Bellows lifted the cup to his lips.

The coffee tasted like hell, for the cream had slightly soured!

During this interval Bellows had been paying no attention whatsoever to his wife's chatter. Now he looked up at her whitely, and her voice came into his range of consciousness.

"And so you see, George," chirped his wife, "even though we make a lot of money compared to some of the people we know, we really ought to think of cutting down expenses. After all, with this war, and everything, we can't be too certain about conditions. Especially since you are in the advertising business, and everybody knows how badly this war has hit the advertising business."

Bellows' jaw went slack. He gaped foolishly at his wife, while through his mind there ran the phrase, "This is just exactly as she said it in the dream, if it really was just a dream!"

Then he said, unaware of speaking aloud: "But it couldn't be a dream, then! It couldn't have been a dream!"

Connie now found it her turn to gape. She looked at her husband in amazement.

"What on earth are you saying, George?"

Bellows was still too white to redden at his wife's words. He could only shake his head stupidly, as if trying to rid it of a fog. Something much more deeply rooted than reason was assuring him that the horrible nightmare he'd experienced hadn't been a dream at all. He glanced down at the paper wildly. Yes, every news story on the front page had been there before him in that so-called dream. And everything else in the pattern duplicated that pseudo-dream, even to the words his wife spoke, the foul taste of the tomato juice, the burned toast and the slightly sour coffee!

George Bellows pushed his chair back from the table and got unsteadily to his feet.

"What's wrong, George?" Connie said in sudden alarm.

Bellows shook his head. "Nothing," he said. "Nothing at all. Just a little groggy. Need some air. I'll take a quick walk."

Connie rose and came swiftly to his side.

"Do you want me to call the doctor, George?"

Again Bellows shook his head. He started for the door, then turned.

"Connie," he said huskily, "how did I come home last night?"

"Why, you weren't out last night," Connie said. "You came home in a cheerful frame of mind about six-thirty. We both sat up and played gin rummy until around midnight. Why? What's wrong, dear?"

"Nothing," mumbled George Bellows, staggering for the door. "I'll be back the minute I get a little air."

OUT in the fresh morning air, George Bellows got a grip on himself. Well, sort of a grip. And after he'd walked half a block, he was able to do a little rationalizing. Rationalizing that included a careful re-summation of everything that had occurred in the "dream" he'd had.

From the re-summation, Bellows was able to recall for the first time since rising, the incident at the south sea-ish night club where there'd been the little Achmet. And then, of course, he recalled the curious little clock.

He remembered, too, the argument he'd had with the little man about fatalism, predestination, and fighting the winds of fate. And he recalled the promise of the little man, after giving him the weird timepiece, that he would be able to relive his nightmarish day.

Bellows felt extremely weak in the knees.

It was preposterous. If there'd been anything a man needed to convince himself that the whole thing had been the poppycock of a dream, it was the mumbo-jumbo of the clock and little Achmet. Such things were utterly impossible.

It was ridiculous, fantastically absurd. Bellows told himself this again and again. But by the time he'd walked around the block and was in sight of his house again, his mind was clear on one thing.

"Impossible or not, ridiculous or not, the damned thing happened to me, and this is my chance to relive this day!"

And so when Bellows reentered his house, he assured an anxious Connie that he felt much better. Assured Connie of that while going into the living room for a look around.

It had occurred to Bellows that he might find the little timepiece in the living room, the curious clock Achmet had given him. He had left it there. But after a brief, futile search, he suddenly realized that if, as he was now convinced, he was living this day over again, the watch naturally wouldn't be about. He wouldn't even have seen it yet!

Connie, coming into the living room, asked: "Don't you want to finish your breakfast, dear? You'd better hurry, if you want to get to work on time."

George Bellows squared his shoulders grimly. Of course he would finish his breakfast. He would finish his breakfast then set forth to prove to himself and posterity that a man can create his own destiny, given half a chance.

Back at the breakfast table, Bellows looked up at Connie and smilingly said: "Everything tastes swell, kid."

Connie looked surprised.

"Thank you, George," she said a little flatly.

As a matter of fact, everything tasted foul. But Bellows was out to change things. To change everything. He'd started off this day the first time with a fight with Connie. He wouldn't fight with her this morning.

"Yes indeed," Bellows reiterated, "this is a dandy morning snack!"

Connie suddenly stood up.

"Do you have to rub it in, George? Do you have to be so sarcastic? I know the tomato juice is flat. I know something's wrong with the cream. It wasn't my fault the toast burned. And now you have to be nasty!"

BELLOWS, mouth full of burned toast, gurgled astonishedly at his wife as she swept angrily from the room. He heard her mules clicking up the stairs to the bedroom.

He swallowed the burned toast and rose hastily to his feet, thinking of following her to set things right. And then he glanced at his watch.

It was twenty minutes to nine. He'd just have time to make it to work. He couldn't afford to go upstairs and placate Connie. He'd have to let that wait until he got to the office. He'd call her from there.

Bellows found his hat where his wife had hidden it, and dashed to the garage. He was already into the stream of Sheridan Road traffic when he remembered about the trouble he'd encounter at the Outer Drive. It would be blocked off.

It was.

A little sickly, Bellows followed the regular Sheridan Road run along toward Lincoln Park. Mentally he lashed himself for having forgotten about this snag in his haste. Unconsciously, he did a bit of weaving and accelerator pounding in his nervous impatience. Then, of course, he encountered the second detour at Sheridan and Broadway, and was forced along the street car ridden, cobblestoned street. The scene of his accident was approaching, and Bellows began to be aware of it.

He fought back the impulse to sneak off into a side street, knowing that it would only serve to slow him until he was late for work, and knowing too, that he would have to thwart the fate of the accident on his own hook.

And then he came to that corner. The corner where, in the first living of this day, he'd had the smashup with the beer truck. The light, as it had the first time, was changing from green to yellow. Bellows knew he had time to scoot across the intersection before the yellow faded into a red "stop" signal.

Grimly, Bellows smiled.

"Not when I know better," he muttered.

He slammed his foot down on the break pedal, obeying the yellow light to the strictest letter of the law. Ahead of him, to the right, he saw the big beer truck barrelling across the intersection.

He'd thwarted fate!

And then Bellows felt a jarring impact from the rear. A jarring impact which knocked him forward against the wheel, smashing his mouth on a spoke.

The roaring of the crash was still in his ears when Bellows climbed dazedly from his machine. Sickly he saw at a glance that a streetcar, coming up directly behind him, had been unable to stop fully when Bellows had jammed on his own brakes. And the streetcar had quite thoroughly pleated his automobile, obviously beyond hope of repair!

For a minute George Bellows was too sickly stunned to do anything but gape. Gape and hold a handkerchief to his swollen and bleeding mouth. The streetcar motorman was climbing from his platform.

BELLOWS hesitated only an instant.

He knew what a wait would mean. Any time spent in bickering here, or accident reports, would make him late to work. And that would mean his discharge.

He made up his mind swiftly. He could settle about this accident later, somehow.

Quickly, Bellows looked about. He sighted an empty taxi and dashed toward it. He heard shouts of amazement and anger behind him as he ran.

Bellows shouted his office address to the driver, adding:

"Five bucks if you get me there before nine!"

The driver nodded throwing the hack into gear. They roared off, leaving a bewildered motorman, an irate traffic cop, and a hooting crowd of spectators to decide what to do with a demolished sedan which was tying up traffic.

Nervously, Bellows settled back and lighted a cigarette. He glanced at his watch and frowned. Then he looked out the window, saw the speed and dexterity with which the driver handled the hack, and knew he had a prayer of a chance of arriving at work on time.

At precisely three minutes to nine they rolled up before the office building in which the advertising firm of Barton and Biddle was located. The driver got his five dollars, and George Bellows raced into the building lobby just in time to catch an express elevator.

Bellows entered the offices of Barton and Biddle at exactly nine o'clock. He nodded to the switchboard girl and the stenographic help in the bullpen, making his way toward his own private office cubicle.

And then he saw the boss, Homer Barton.

Barton was moving from the other side of the office to intercept him. Bellows looked up at the clock on the office wall to reassure himself. Yes. It wasn't any later than nine. Barton could have nothing to gripe about.

"Oh, George," Barton's voice came to Bellows. "I'd like to talk to you a moment."

Bellows waited for Barton to reach him. The fat, pink faced little fellow was smiling in sort of a hesitant kindliness. Bellows frowned. There was just something in the attitude of his boss, nothing obvious, to suggest disappointment.

"I'd like to talk to you alone in your office, George," Homer Barton said.

Still frowning, Bellows led the way into his private cubicle and turned to face his employer. Homer Barton closed the door carefully behind them and coughed apologetically.

Suddenly Bellows had a horrible premonition concerning the faint evidence of disappointment in his boss' manner. He had the definite sensation that Barton had been waiting for him, hoping he would be late.

"What I have to say isn't pleasant, George," Homer Barton said in his cold little voice. "And frankly, I wish I didn't have to say it to you personally this way."

Bellows watched Homer Barton in a sort of dull fascination. The little man wet his thin lips.

"Our business has been falling off considerably, especially in our radio department. You are our radio copywriter, of course, and so when the necessary, ah, adjustments had to be made in our copy staff it was decided we'd best turn your work over to some of our magazine and newspaper copywriters."

Homer Barton paused to smile sadly at George Bellows, deliberately letting the implication of his words sink in.

"You mean I'm canned?" Bellows said huskily.

"I'm sorry. George. We'll give you the best of recommendations, and a month's pay for dismissal. But it has to be done."

Bellows nodded. "Sure," he muttered. "Sure. Okay. I'm off starting now, okay?"

"That will be all right," said Homer Barton. "You can pick up your check at the switchboard. I had it made out in advance." He extended a cold, damp little hand which Bellows took and shook briefly.

Barton was at the door when Bellows asked: "Incidentally, you were hoping I'd be late this morning, weren't you?"

Little Homer Barton looked at his ex-employee startledly. He flushed a guilty crimson.

"Why of course not!" he snapped....

IN THE more or less well known figure of speech, George Bellows' head was bloody but not quite bowed when he walked gloomily into Mindy's bar some thirty minutes later.

A growing sense of futility, a sort of numbing despair, was beginning to settle on Bellows' shoulders, true enough. His bucking of the winds of fate to that moment had been scarcely successful. He'd altered the course of his day as consciously as he could to prevent the pattern from taking on the same tragic aspects that it had the first time. But in only the minor, inconsequential details had the pattern changed. And now he found himself no better off than he'd been in the first living of this day when he'd slumped dejectedly onto a barstool in Mindy's.

He had eight hundred dollars in his pocket, like the first time, and Mindy was smiling asking him what he'd have, ditto the first time.

"Give me," Bellows said, and then he hesitated. He squared his shoulders slightly, deciding once more to vary the pattern. The first time it had been brandy.

"Give me a scotch and soda," Bellows said defiantly.

Mindy looked at him as if he wondered about the defiant voice, but he went off to get the drink nonetheless. He'd no sooner returned with it, than Louie, the dapper bookmaker sauntered into the place and slid into a stool beside George Bellows.

Bellows looked up, startled, from his untasted drink. Again the pattern was slightly varied in inconsequential detail. When Louie had entered in the first version of this day, George Bellows had been already slightly stewed. Now he was only starting.

"Hello, Georgie," Louie said affably. "Yuh look as though yuh lost yuh dawg."

"You said that before," Bellows said flatly.

"Huh?" The dapper little bookmaker was taken aback.

"Skip it," Bellows advised.

"Sure," Louie said. "Sure."

"How's the horse business?" Bellows asked casually, taking his first gulp of scotch.

"Not good, not bad," Louie replied cautiously.

"That's good," Bellows said dryly; "it's not bad."

Louie blinked and didn't answer.

SUDDENLY Bellows was aware that he would be achieving a supreme triumph over fate if he would just drink and get up and walk the hell out of there. Then there would be no bet, and no loss, and a considerable part of his previous grief would not happen.

Bellows drained his scotch and started to get up from his stool. Suddenly a foolish expression crossed his face, and he snapped his fingers.

"My God!" Bellows exclaimed aloud. "What an ass I almost was!"

"Huh?" asked Louie.

"Got a form sheet?" Bellows asked excitedly.

Louie nodded. "Sure." The racing sheet was out of his pocket and into Bellows' hand in an instant.

George Bellows, excitedly running his hand along the form, felt the first elation he'd experienced since all his trouble began. Elation and sardonic amusement at the boner he'd almost pulled. For he had almost walked out on Louie. Walked out on Louie the bookmaker when he, George Bellows, through having lived this day before, knew positively what horse was going to win the first race at Arlington!

What was the name of that long shot that beat the horse he'd picked the first time? Bellows found it with an excited exclamation, jabbing his finger beneath the name. Merrily, that was it!

And Merrily was priced at twenty to one.

"Yuh wanta plank a bet?" Louie asked.

"You bet your sweet life I do!" Bellows exclaimed.

Louie nodded toward a corner.

"We bettah go ovah to that corner," he suggested. "We don't wantah place no bets in fronta the woild."

Bellows found his billfold, and clambered from the stool to follow dapper little Louie over to the corner of the bar. Louie had eagerly produced a ticket sheaf and a pencil. He looked expectantly at Bellows.

"How much?" he demanded. "And on who?"

"Seven hundred dollars," Bellows said. Somehow he felt a little more ethical, working on his advance knowledge, in only betting the same amount as before. "Seven hundred dollars on Merrily, in the first. The list price is twenty to one. What'll you pay?"

There was the same startled look from the little bookmaker that there'd been before. But then he regained his composure and said, nonchalantly, "I kin oney pay, say, fifteen to one, Georgie. I can't give no track odds, you know that."

Bellows grinned. "All right. Fifteen to one. Seven hundred bucks. That makes ten thousand five hundred dollars you'll have for me, Louie, when that race is over." He added, "Better get to your bank right now."

Louie held out his hand. "If you win, Georgie," he corrected him. "You gotta longshot there. Hand ovah the seven hundid iyon men, Georgie."

Bellows gave Louie the bills, took his ticket in exchange. He patted the little bookmaker on the shoulder.

"Don't let it throw you, Louie, when Merrily romps in."

Louie obviously thought that was very funny. He grinned from ear to ear, like Peter Rabbit....

IT WAS an almost boisterously happy George Bellows who inhaled the fresh, clean air of the lakefront several hours later. An already triumphant Bellows, who had fought fate relentlessly until he had discovered the chink in its armor.

He had left Mindy's immediately after negotiating his magnificent wager with Louie. Left Mindy's, again changing the pattern of his first living of this day. Changing it, so far, in detail only, but in details which would this time mean victory.

He had sought the sunshine and healthful lake breezes in direct and conscious contrast to the routine he'd followed in his first living of this day. Then he had sought only the solace, dubious as it was, of brandy and more brandy.

"Ahhh, but it's so different now," Bellows told himself. "So very, very different."

And so for another hour he looked at the gulls and the lake and the trees and felt quite supremely happy. Finally, his watch told him that it was just about time for the first race at Arlington to be run.

Confidently, Bellows found a restaurant which he sometimes patronized. A restaurant where they always had the day's races blasting forth from the radio.

There Bellows took a seat, noting that the racing program had already started, and the preliminary remarks concerning the first race were already under way by the announcer.

Bellows somewhat smugly ordered a cheese sandwich on whole wheat and a glass of milk. Then with this definitely unimpeachable repast before him, he settled back to listen.

Everything Bellows had heard the first time was once again repeated by the announcer, so he paid scant attention to the radio until the race was due to start. Even the worry of his wrecked automobile and lost job were gone from Bellows' mind now.

Ten thousand five hundred dollars would keep the wolf quite comfortably from the door until he started at another agency. And as for the automobile, Bellows was quite willing to content himself with the realization that gas rationing and tire shortages would soon make all such luxuries unfeasible anyway.

And so Bellows contemplated his good fortune and waited until the announcer finally came through with his electric words.

"They're off!"

Bellows sat forward a little at these words, to be sure. But his smile was bland as the announcer, exactly as he had in the first living of this day, recounted the exciting running of this race.

Despair, as he had the first time, led most of the way around. Castaway, also as before, threatened constantly from the backstretch on. Little mention was made of Merrily, but Bellows knew that his horse wasn't due for mention until the driving home stretch when it broke the finish line ahead of the rest.

It was over very quickly. Over just as Bellows had known it would be. Over just as it had been the first time. The announcer was bleating excitedly.

"Merrily! Yes, Merrily wins by a nose in a tremendous last stretch drive. Second was Despair, third was Castaway. And that's the end of the first race at Arlington Park, run at—"

Grinning triumphantly, Bellows paid for his milk and cheese-sandwich and left the restaurant. He decided to go directly to Mindy's where he could leave word with the bartender for Louie. Word to meet him there later, say at five, with the ten thousand five hundred dollars winnings.

MINDY'S was only ten minutes away by cab, but Bellows, in his mood of exuberant triumph, decided to walk it. He arrived there a little less than half an hour later.

Casually, Bellows ordered a ginger-ale, and then, just as casually, asked Mindy if Louie had been in.

"Yeah, sure about ten minutes ago," Mindy said. "Which reminds me, he left you this."

Mindy walked over to the cash register and pulled forth a long envelope, brought it back to Bellows.

"He seemed white and shaky about somethin'," Mindy said, handing the envelope to Bellows.

"He should," Bellows grinned. He took the envelope. Louie paid off fast; he had to say that for him. And then Bellows frowned swiftly. The envelope was not a fat bulging thing that might contain currency. Instead it seemed to have only a thin sheet of paper in it. Bellows tore open the envelope wondering if Louie paid by check.

The check was not a check. It was a brief, horribly explanatory note.

Dear Georgie: the sprawling scrawl read.

Don't like to do this, but can't help it. Your dough is down the drain and I don't know how I can pay off. If you're ever in California, look me up.

Yrs. regretfully,

Looie.

George Bellows felt suddenly as if he wanted to vomit. The room seemed to swim grayly around him, and he had to hold onto the bar for support. This was his triumph over fate. This was his so-successful bucking of an already predetermined destiny. No matter what he did, or how he fought, the pattern could never be changed basically.

No more car. No more job. No more seven hundred dollars. Just like the first living of this day. George Bellows' head was figuratively very bloody, but now it was definitely bowed.

Through the dim fog of despair and sick futility that shrouded him, he heard his voice saying desperately to Mindy:

"Bring me a bottle of brandy. A nice big bottle of brandy. You can skip the soda."

Mindy merely raised his eyebrows. But he brought out the bottle....

EVEN at the start of the bottle, Bellows was conscious of one unshakable fact. His destiny for this day—as it had undoubtedly been for all the days of his life from birth to death—was rigidly patterned, unalterably sealed. There was no fighting it. No bucking the winds of fate.

He'd tried. He'd tried with a thorough knowledge of the bad luck that lay ahead of him, and still he hadn't been able to dodge any of the tragedies he knew to be coming.

And what made it even more terrible was his positive knowledge that the final tragedy of the day was also inevitable. He would lose his wife, to finish the ironically futile battle. There could be no preventing that. Connie, just as she had in the first living of this day, would walk out on him in disgust. Nothing could prevent it. Nothing in the world that he could possibly do.

Staying sober wouldn't prevent it. If he stayed sober some other fiendish complication would step in to carry out the preordained destiny. So to hell with staying sober.

"To hell," Bellows summed it up neatly, "with everything!"

Halfway through the first bottle, George Bellows became squintingly philosophical, and since he was practically the only customer in the place at that hour, he was able to commandeer Mindy's ear.

"Y're licked already, chum," Bellows said carefully, pointing a none too steady finger at Mindy's chest. "Wyncha give up? Wyncha go in fifty-fifty onna gun wi'me? We'll commit sooshide, huh?"

"Now," said Mindy moderately and with practiced tact, "I don't know about that."

"Y'oughtta know," Bellows insisted. He lowered his voice to a confidential whisper. "I know," he hissed.

Mindy smiled tolerantly and lighted a cigarette on which George Bellows had already wasted half a pack of matches.

"Thanksh," Bellows muttered parenthetically. Then: "Y're lucky. Y'don't know y're licked. I do."

Mindy wandered away to fix a drink for a customer who'd just entered. Bellows gravely began a sotto-voce argument with himself. The summation of it seemed to be that the world was the miserable place it was because of small dark gentlemen named Achmet, or Allah, who gave people curious clocks and ruined their lives for them by making them see how futile everything was.

To an outsider, a casual listener, Bellows' self argument would have been scarcely coherent. But to him, it made much sense, especially after pondering it a little longer.

By the time he'd finished his bottle, Bellows had determined to seek out the swarthy, dark-bearded little chap named Achmet, or Allah, or whatever it was, who'd been responsible for his having to endure this tragic day of proving to himself the futility of struggle against fate.

BELLOWS found a cruising taxi on Michigan Boulevard, and managed to make the general direction in which he wanted to travel vaguely clear to the driver.

Then he leaned back and slept.

Ten minutes later the cabbie and a doorman were shaking him into wakefulness.

"Come on, buddy," the driver said impatiently. "Isn't this where you want to go?"

Bellows opened his eyes a moment to blink around.

"Allah here?" he demanded.

"Pickled to the roots," snorted the doorman disdainfully. "Take him somewhere else; we don't want him here."

The driver shook Bellows again. Again Bellows opened his eyes.

"Listen, Buddy," the driver pleaded, "where do yuh wanta go?"

"Go shee Allah," Bellows mumbled with vague determination. He closed his eyes and began snoring again.

"Look in his wallet," the doorman said. "Maybe his address'll be there. You can take him home."

George Bellows, unconscious of the fact that fate again was bringing him into an inescapable encounter, snored happily onward. The driver shrugged.

"Okay. I don't like to do that. But it's better'n dumping him into the street like this." He proceeded to roll Bellows over to get his wallet....

IT WAS approximately twenty minutes later when the taxi drew up

in front of the Bellows' neighborhood residence. It being late afternoon, the arrival gained considerable attention from most of the block's residents.

With no little effort, the driver at last succeeded in waking George Bellows. And on climbing unsteadily from the cab and blinking in the sunlight, Bellows became aware of where he was for the first time.

He knew he was in front of his house. He knew that he was drunk. And he remembered that he faced the final and by far most terrible tragedy of the day. This was the scene in which Connie would leave him.

Bellows shoved some bills into the cabbie's hand and turned to make his weaving way up the walk. Alcoholically fogged though he was, he sensed that the ancient Roman martyrs must have felt much as he did now when they walked into the arena to face the lions.

He fumbled for his keys as he climbed the porch steps. He dropped his billfold and keys and cigarettes, and was bending over on all fours to retrieve them when he heard the front door open. He looked up to see Connie standing there in the doorway, staring at him aghast.

Bellows retrieved his things, stuffed them haphazardly into his pocket, and swayed back up on his feet.

He felt a foolish grin cracking his mouth, an uncontrollable grin.

"Lo, Connie," he mumbled. "Look lovely."

THEN he navigated the rest of the steps and stumbled past her into the house. Connie still hadn't said a word. Now he heard her slam the door behind him.

He stumbled around to face her, the silly grin still on his face.

"What does all this mean?" Connie asked quietly. "And tell me also what you've done with the car."

"Carsh smash'tup!" Bellows said. "Shtree'car hit it. N'er be worsha nickle again."

"Oh, George!" Connie gasped.

"I alsho don' hawa job anymore," Bellows hiccupped. "An I losh alla money we got lef onna horsh."

Connie's expression was one of sick horror. Her pretty gray-green eyes were moist, and suddenly twin tears ran down her cheeks.

"Go 'head," Bellows said. "Now leave me. I'ma bum, thash wot. Leave me 'n get it o'er wish."

And then, to Bellows utter amazement, Connie's arms were around him and she was hugging him tightly and sobbing.

"Oh, George. Oh you poor darned unlucky George. What a positively horrible day you musta have had. Don't think I'm angry, George. I couldn't be angry when you're so utterly down. I couldn't in a million years. You, poor, poor miserable George!"

Dazedly, Bellows let Connie lead him into the living room where she made him lie down on the sofa. He was still too stunned to speak when Connie came back with cold towels and an ice pack.

But the sobering impact of the ice pack and cold towels was nothing as compared to the shockingly sobering impact of Connie's utterly reversed behavior.

"I'm making some black coffee, darling," she said smiling bravely. "You just lie still, and don't worry about anything. It's all going to be all right, honey. You wait and see. You'll find another job, and the car doesn't mean anything. I've a little money I've been saving on the sly. It will tide us along."

Even had he been utterly sober, Bellows wouldn't have been able to figure it out. It was utterly contradictory. Completely, totally out of line with what had happened the first time. And for no reason. Absolutely no earthly reason.

AN hour later when Connie went out to get his third cup of black coffee, Bellows, still beneath the cold towels and the ice pack, was able to figure out the only possible explanation for it all.

"It's simply that she's a woman," he thought, "and there is no rhyme or reason to any reaction of the female of the species. No one, not even Fate itself, can determine how a woman will react from one instant to the next."

And when Connie came back with the third cup of black coffee, the smile Bellows gave her wasn't the least bit silly. It was brimming with appreciation and the deepest affection man can offer to the one imponderable, incalculable quotant in the otherwise inflexible scheme of Fate—woman.

For he knew that as long as the species existed in the world, man need never fear any predetermination of anything, anytime.

Connie saw the smile, and asked tenderly:

"What are you thinking of, George?"

"Eve," Bellows grinned. "Mother Eve. She certainly threw a rigidly ordered world beautifully out of balance when she entered the picture. And am I glad!"

Connie gently adjusted the ice-pack on her husband's forehead and wondered vaguely what the hell he was talking about....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.