RGL e-Book Cover 2020©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2020©

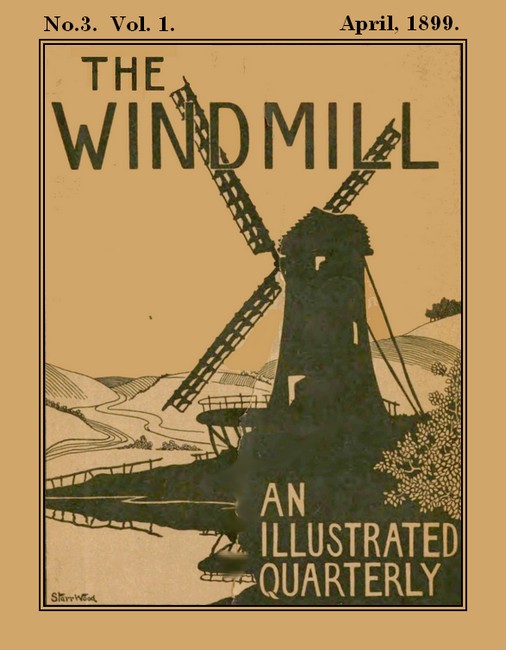

The Windmill, April 1899, with "The Lady of the Morass"

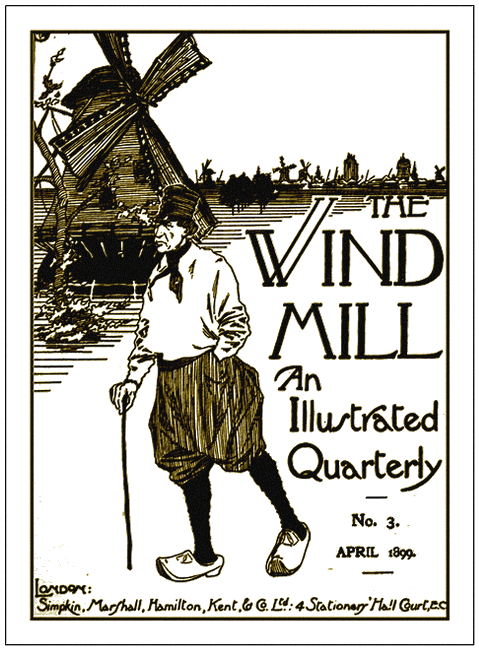

Frontispiece, The Windmill, April 1899

WROXHAM had just come in, big, self-satisfied, and well-dressed. With a cigarette between his teeth, and his legs a little apart, he was planted in front of my canvas—and I knew very well that he was preparing for me something in the nature of a criticism.

"Not bad, old chap," he said at last, tapping the easel with his riding whip. "Not bad at all. All the same, you've made a mistake."

I nodded, and invited him to proceed. My feelings, I assured him, were hardened. As though Wroxham ever considered anyone's feelings!

"Fairly good subject" he went on amiably. "Young man on the road to ruin—Modern Rake's Progress, or something of that sort you'll call it, I suppose. Young man seems to be stepping into some sort of a morass. Behind him cottage, home no doubt, light in the window, and a shadowy sort of girl, symbolical of goodness, and all that sort of thing of course, waiting for him and hoping he'll come home to tea. Lady emerging from morass appears to be offering different sort of invitation. I don't know how it strikes you, Jack, but I should say the odds were in favour of lady who is winking."

"She is doing nothing of the sort," I expostulated, indignantly.

"Not actually, perhaps," Wroxham continued, calmly, "but morally winking. That's where you've gone a bit wrong, Jack. Your allegory's all right, but you've made it too straightforward. Good woman one side of canvas, wicked woman the other, tempted young man between. People look and pass on. That isn't what you want. You want 'em to stop. They won't"

Now it is possible that I might have shut Wroxham up and changed the subject, but for the fact that something in his words appealed to a vague discontent which I myself felt for the picture. As it was, I strolled to his side and looked over his shoulder. Wroxham was evidently flattered, knowing quite well the usual value I set upon his criticisms.

"I am going to use a hateful word," he continued, cheerfully, "but I use it as a friend. Everything else is good, but you have damned your picture with a distinct note of conventionality."

I was quite humble now. Wroxham was right. I hung upon his words. Would he stumble upon the weak point? He did.

"It is your conception of the lady of the Morass which is at fault," he went on confidently. "You have reverted to a worn-out type. That sort of thing," he waved his jewelled fingers towards the left hand corner of the canvas, "represents wickedness to Tom, Dick, and Harry—for whom you do not paint There is the ordinary superabundance of hair, the heavy-lidded eyes, the sensual mouth, the full swelling limbs, which, as usual, the draperies seem to reveal rather than hide.

Quite a wrong idea. The wickedness which fascinates to-day is the wickedness which has the guise of innocence. You wanted a girl for your model, not a woman; slim, dressed in black, with the face of a Madonna, and eyes turned heavenwards. You want to puzzle people by showing them the wickedness of the soul, and contradicting it in your delineation of the body. Quite simple, really—a matter of knack and the right model. Nice picture, but you haven't quite hit it."

"What a blackguard you are, Wroxham," I answered absently.

He shrugged his shoulders, and left soon. Wroxham never liked to be called names. But, late that evening, whilst I was smoking a despondent pipe, I had a note from him.

Hill Street, W.

Good for evil, old chap. I will give you a chance to redeem your picture, and set people's tongues a-wagging. The model you want is dancing every night from 8.50 to 9 at the Walworth Star Music Hall. I haven't seen her, but I know a chap who has.

Wroxham.

Of course I tossed his note into the fire. Equally, of course, I was at the Walworth Star Music Hall a few minutes past eight on the following evening. The place was new, gorgeous with plush and mirrors, reeking with vulgarity and tobacco smoke. I mingled with the crowd, and leaned over a balcony—prices were high, considering the neighbourhood, and I could not aspire to a box. It was a long time since I had been in a place I disliked more heartily. There was none of the cockney fun. Vulgar, perhaps, but with some pretence to humour of the East End Music Hall proper—the performance and surroundings were more like a weak and ghastly imitation of Leicester Square. There were a few sickly-looking youths in evening clothes, a sprinkling of unsexed women, whose weak faces and overpainted cheeks proclaimed an appeal to tastes less exacting than the palaces across the water. The performance of its sort was good enough, but I had no ears for it. It was one of my bad times, and a weariness was upon me. Even a Philistine like Wroxham had been able to lay his finger upon the weak spot of my work. That, surely, was degradation enough.

When the girl came, I was galvanised into a sudden eager interest. There was no mistaking her, or the fact that she was a favourite. She came on plainly dressed in a black evening gown, tall and slim, with a beautiful oval face and sad, wistful eyes. I was amazed at her reception. What had they in common with her, or she with them? These brutish-looking men and women, these dissipated boys, and hard-faced, joyless girls. She sang a little ballad very sweetly and very well. I rubbed my eyes and looked around, wondering more than ever at the air of expectance in all these unwholesome-looking faces, at their moist, weak eyes, and ugly, grinning mouths. She left the stage for a moment. There was a little murmur, and she reappeared, half dressed, shameless, hideously at her ease. She sang a song, to which I, no puritan, closed my ears; she accentuated its pruriency with gestures quick but unmistakable; the knowledge of evil flashed seductively out of her soft eyes up at the rows of applauding men and laughing women. I groped my way out into the streets and wandered away to the river, with the cold night wind cooling my hot cheeks, and the feeling that I had stood for once face to face with black sin. My hands were hot and damp, there were beads of perspiration on my forehead. All that was worst in me seemed suddenly called into life.

NEVERTHELESS, I knew that Wroxham was right, and in a cooler frame of mind I wrote to her. For two days there was no answer. On the third evening I received a short note. She did not quite understand my request. Was it her portrait that I wished to paint, or did I merely wish to introduce her into a picture of my own! If the former, she regretted that she must absolutely decline. If the latter, she had had no experience as a model, but she would not object to consider it if I would give her the further particulars.

I wrote and asked her to come to tea the next day—and she came. When, in response to her knock, I threw open the door of my studio, she walked in. I failed at first to recognise her. She was very quietly and very plainly dressed. Yet she carried herself with a certain elegance of bearing which left no room for doubt as to her antecedents and her past associations. She held out her hand and looked up at me frankly.

"You are Mr. Densham," she said. "I have come to see you about your picture. Is that it? May I look?"

But I stopped her quickly. In fact, my courage was almost gone. How was I to show her my canvas? To explain to her what it was that I required? To the woman who had sung that hideous song at the Star Music Hall I would have explained it with a jest, with all the cynicism indeed of Wroxham himself. But to this girl, whose eyes met mine so frankly, and the very curve of whose lips when she smiled reminded me of one of Guido's Angels—Why, the very idea revolted me.

"Don't look at it now," I said, hastily. "Let us talk first."

Dick's servant, borrowed for the occasion, brought in tea, and we talked together pleasantly of many things. At last, however, she looked at her watch, and rose with a little exclamation of surprise.

"Really," she said, "I had no idea it was so late. You must tell me about your picture now at once, please, Mr. Densham."

She moved towards it, but I stopped her.

"Will you forgive me," I said, "if I plead guilty to having made a mistake. You must remember that I have only seen you upon the stage, and I am sure that I have made a mistake. That is all. If you will let me come and see you sometime I should be so glad."

She looked at me, puzzled at first, and then with a slight hardening of the features.

"I am going to see the picture," she said, and she brushed me aside with a little imperious gesture.

I heard her sweep the covering from the canvas, and I saw her take a quick step backwards. The figure which I desired to remove, for which, indeed, I had desired to substitute her, was only partially obliterated. The coarse limbs, the suggestive droop of the body, the sensuality of the face, were all too readily apparent The girl looked steadily from the canvas into my face, and to have escaped at that moment I would have thrown the picture into the streets and taken my chance of starvation for the next six months.

"I am very sorry," I faltered; "please remember that I knew nothing of you. Of course, my suggestion was an insult You won't forgive me, of course. I don't deserve it. Only, please believe that if I had known you I would never have made so ghastly a proposition."

She was still looking at me in a curious, intent way. Since she had seen the picture there was a distinct change in her. A certain softness and delicacy of voice and appearance seemed to have left her. There was something ominous and unpleasing in the deadly quiet of her manner and her unruffled tone.

"I wonder," she said, "did you see me by chance at the Star, or was it the suggestion of someone else that I might serve to represent for you—that!"

Her hand flashed out with a quick, dramatic gesture to the canvas. I tried to draw her away from it, but she would not move.

"It was at the suggestion of someone else," I said. "Someone who was obviously mistaken in you."

"By no means," she answered, coldly. "I think that your friend showed admirable judgment. I want to know his name."

"I do not think that he had ever seen you," I said. "In fact, I am sure that he had not"

"Nevertheless," she answered, "I want to know his name."

"It was an artist himself," I said, "Philip Wroxham."

If I had not been watching her closely I would have said that the name left her unmoved. But my eyes were fixed upon her, and I saw something that was like a cold shiver pass through her frame, and she half closed her eyes, as though in pain. For several moments she did not speak. I made some stumbling remark, to which she returned no answer.

"I wonder," she said abruptly, "if you mind fetching me a glass of water!"

I left the room in search of it. When I returned she was still standing before the picture, but everything which was strange in her manner had disappeared. She looked round at me with a very sweet smile—she was quite her old self again.

"I am so sorry to have troubled you," she said, sitting down in my easy chair.

"Now, I want you to tell me how much time would you want me to give you, and is the posing very difficult! You must remember that I know nothing about it."

I looked at her with a start.

"You are not going to pose for that," I cried.

"I mean to," she answered, quietly. "I should like it"

I shook my head decidedly.

"It is ridiculous," I said. "I will not have you. You are not suitable."

She rose to her feet, and came over to me. Standing with her hand resting lightly upon her hip, her head a little on one side—just as she had stood before she bad sung that song.

"Am I not!" she whispered.

I pushed her away almost roughly, but she only laughed. The face which had looked into mine was the face of the prima donna of the Star. There was that in it which had driven me out of the place and made me ashamed.

"Am I not!" she whispered again, softly. "I shall be here to-morrow at three."

I PAINTED the picture, and I knew that when once I exhibited it the days of my obscurity were over. I showed it to no one, and I lingered over those last few finishing touches, indulging to the full in a curious reluctance to part with it or to let any other eyes save mine and her's rest upon that terrible figure. And when it was finished I sat down before it, and I felt that I would give years of my life never to have painted it, never to have seen that wonderful face which looked now from my canvas as I had seen her look at the Star Music Hall. I smoked my pipe furiously. I glared at it with frowning face and a curious but very potent sense of guilt. How had I dared to make capital out of a woman's corruption. If she was that, God help her—but I knew another woman, and I longed to believe in that other one. I had done her an evil turn surely to immortalise the blackness of her soul. Somehow I felt that if this work brought me success, as I never doubted but that it would, the fame and the gold would come to me tainted and besmirched—a veritable blood-offering.

Wroxham came in while I sat there. I would have hidden the picture, but I was too late. Already his eyeglass was fixed, he was preparing, I could see, for something elaborate in the way of criticism. I moved aside, and nerved myself to listen to his flow of words.

But none come. When I looked up surprised at his long silence, I saw that he was not capable of uttering any. His eyeglass had fallen and lay shattered to pieces upon the floor. A curious grey pallor seemed to have crept into his face. He swayed for a moment on his feet, and then stood perfectly still. His eyes were dilated and rivetted upon the figure in the painting, and he looked as one who sees those things which it is not good for mortals to know of.

When he spoke, his voice was hoarse, and seemed to have come from a long distance. He spoke without looking at me or moving his eyes from the picture.

"Who is she? Where did you find her?"

"You should know," I answered, bitterly. "You sent me to her. It is the girl at the Star Music Hall."

His white lips murmured a woman's name. "Give me her address," he said. She came out from behind the screen. "I am here," she said, calmly.

Wroxham gave a little cry and started back. Then he looked from her face back into the picture.

"Is it my work?" he asked her.

"It is your work," she answered.

He took up his hat and groped towards the door. His knees were shaking, he seemed suddenly to have aged ten years.

"Then may God have mercy upon me," he said, in a dull, stricken tone. "May God forgive me."

She stood by my side, tremulous, a little awed. She looked at herself with horror.

"Am I—like that?" she moaned.

I set my teeth and caught up a knife. In a moment the canvas was in shreds. I flung it upon the floor and set my heel through it.

"You are not like it," I cried, passionately. "You never will be like it again. Promise."

She lifted her eyes to mine.

"I never will," she whispered.

BUT that night she sang her old songs at the Star Music Hall, and a broker's man took an inventory of my few belongings and shared my solitary chamber. Wroxham, I heard afterwards, was the life and soul of a brilliant little supper-party given by himself and half a dozen others to the ladies of the Frivolity Theatre.

E. Phillips Oppenheim.

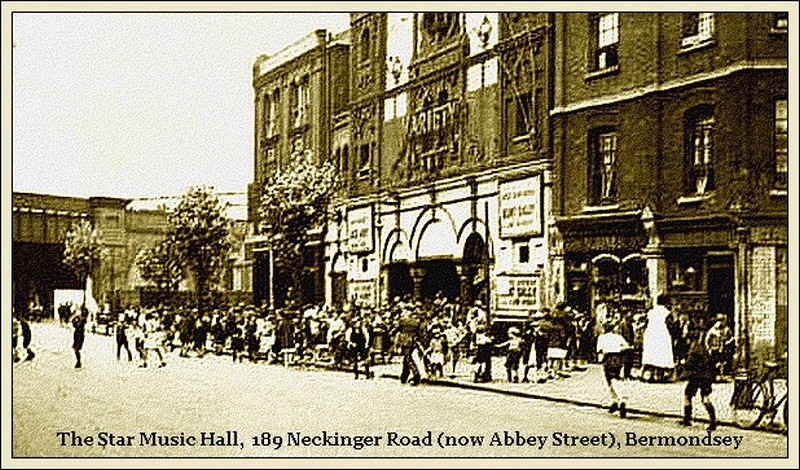

THE Star Music Hall which Oppenheim describes in this story is presumably the one shown in the following photograph.

Oppenheim refers to it as the "Walworth" Star Music Hall. However it was actually situated in the adjacent borough of Southwark. —R.G.

A typical British music hall poster

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.