RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

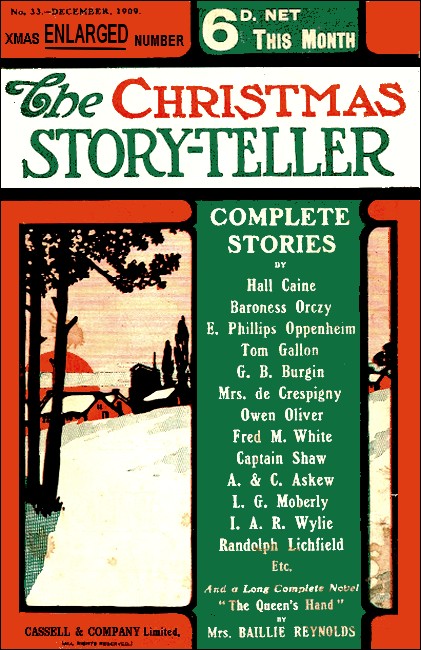

The Story-Teller, Dec 1909, with "The Tragedy of an Unspent Life"

THE editor took the floor, actually as well as metaphorically, it being somewhat past his usual luncheon hour. The discussion however, in which the little group of his fellow- clubmen were engaged had proved interesting.

"My point," he declared with a note of finality in his tone, inspired by the faint odour of roast mutton and the vision of his favourite table filling up, "is this. We do want sensational fiction. The public want it, and therefore we want it. Personally, I don't blame the public. These are strenuous days and the man who reads the ephemeral fiction for which we are responsible must be diverted. But the difference between us is this. I don't think that you fellows quite appreciate the possibilities of sensationalism in—shall we call it literature?"

"The possibilities of sensationalism," a youthful journalist repeated softly.

"Exactly," the editor assented. "I repeat that we do want sensational stories. The trouble is that the moment you hear the word you associate it entirely with blood-curdling murders, Nihilists, revolutions, beautiful velvet-eyed women with daggers in their corsages, and mysterious Dr. Nikolas tracked to their doom by the ultra-modern prototype of Sherlock Holmes. You turn out some good stuff, and I print it when I can; but you are all too flamboyant, too obvious. There is a species of sensationalism lying ready to your hands, which would suit me and would suit my readers, yet which has no kinship with such vigorous happenings."

"We are your humble disciples," a well-known writer of short stories remarked. "Show us the way to this new land of promise. Teach us where to climb or where to dig. We carry the empty hod of necessity, not of choice."

"To know these things," the editor answered, "is that part of your craft which may be reckoned genius. It is mine only to recognise it. Still," he added, looking across the room, "I will give you a hint."

"Bravo, Widdowson!" the youthful journalist murmured, producing his notebook and pencil. "Go ahead, I see the road to fame clear at last."

With an almost imperceptible gesture the editor directed their attention to a man who was just leaving the room. He was short, rather thick-set, fair, pudgy-faced uninteresting. He was dressed in elaborate clothes, which failed to improve his appearance. He betrayed his self-consciousness even in his awkward efforts to open and close the door. "There you are, then," the editor declared, strolling off to his lunch.

"Follow that man home, look into his life, and write me his history. I want no more."

JOHN DUDGEON, on leaving the club, stepped into his

magnificent automobile, and was driven to his palatial residence

in Park lane. Of the manservants who opened the door and relieved

him of his overcoat he ventured an enquiry, the answer to which

filled him with imperfectly concealed disquietude. He smoothed

his hair in the looking glass, however, pulled down his cuffs,

thrust his hands into his trousers pockets, and, with the air of

a man who embarks upon a forlorn hope, suffered himself to be

ushered into his own dining room.

There were seven people lunching at a delightfully arranged round table. Two of the guests were well-known actors, one was the leading lady associated with the older of them, another a writer of brilliant comedies. There remained two women who were strangers to him, and his wife. They were all very well-bred people, and they received him quite civilly. His wife's uplifted eyebrows might, of course, have been taken as an indication of surprise, pure and simple, the silence which followed his entrance, as a compliment. John Dudgeon, very anxious to do the right thing, shook hand laboriously with every one of his guests, and squeezed himself ungracefully into the chair which had been provided for him. Thereupon he smashed his wineglass, asked his recently divorced neighbour after her husband, blew his nose loudly from sheer nervousness, and became negligible. It was not for him to know that the symphony of the lunch party was entirely destroyed.

During the meal his wife addressed but one remark to him, glancing disparagingly the while at his clothes.

"Have you been riding this morning, John?" she asked.

"Not this morning," he answered a little sullenly. "It looked like rain."

She turned away with the faintest shrug of her expressive shoulders. One of the two actors, who wanted a backer, thought he saw his way clear to opening up a conversation with his host.

"Do you ride a great deal, Mr. Dudgeon?" he asked.

"Very seldom indeed," the master of the house replied with a terseness which almost unnecessarily emphasized his distaste for the subject of conversation.

His wife, who had heard the question and reply, intervened. "Mr. Dudgeon is not used to horses," she said drily. "He has only just commenced to ride, and I am afraid that he does not take to it very readily."

John Dudgeon, who risked his life most mornings to please his wife, and whose exploits in the saddle were absolute nightmares to him remained silent. The conversation drifted away, passed once more over his head, the jargon of a foreign tongue, to bewilder him, incomprehensible. Yet there was a difference since his advent, and he knew it. He said nothing. He interfered with nobody. Yet his presence there was like a dead weight. The conversation never lost a certain note of self-consciousness. Very soon after the coffee and liqueurs had been brought the luncheon party dispersed.

John Dudgeon followed his wife into her room. It was a very beautiful apartment, filled with yellow flowers, decorated in pure white, and crowded with French furniture of the best period. There were all sorts of feminine trifles about—books, music, photographs, watercolours—a woman's room, obviously, a woman of taste, too and refinement. He looked very much out of place there, and felt it; but he was lonely.

"I'm afraid you didn't care about my turning up to lunch to- day, Isabel," he said, fingering one of her knick-knacks awkwardly. "You didn't say that you had people coming, and I was sick of the club."

"It was a little unfortunate, certainly," she answered coldly, "especially as they were not people in whom you were likely to be interested."

She stood as though waiting for him to go, but he did not move.

"What are you going to do this after-noon?" he asked lamely.

She looked at him with that questioning expression which he hated. She seemed half-amused, half-impatient. She was wearing a blue gown—the colour which became her best—and turquoise earrings, which she had selected and he had paid for a few days ago. She was a very beautiful and a very graceful woman, and his eyes, as he looked at her, were hungry.

"My dear John," she expostulated, "what on earth does it matter what I am going to do? First of all, if you must know, I am going to rest for an hour—as soon as I can be quiet. You had better go and play golf, hadn't you? The afternoon is quite fine."

"Yes," he answered in a dull tone, "I suppose so!"

"Do you mind sending the car back for me and returning by train?" she asked. "One of the tires is off the electric brougham, and I have lent my mother the Daimler. The trains are just as convenient for you, are they not?"

"Certainly," he answered. "I will send the car back."

She was evidently expecting him to go—yet he lingered. She was quite a beautiful woman, and he was such a fool!

"I am very sorry about luncheon, Isabel," he repeated. "I shouldn't have come home, but I had an idea that I should find you alone."

She waved the subject away.

"It doesn't really matter," she declared in a resigned tone. "I always think that a man is better at his club for luncheon, though. Now you must please run along. I want Estelle to come in and make me comfortable for an hour."

AFTER that there was really no possible excuse for him to

linger. He changed into more suitable clothes and drove down to

his golf club a dozen miles or more from London, taking care to

send the car back the moment he had arrived. He found no one to

go out with, and pottered round alone, playing, as usual,

execrably. Afterwards he had some tea and wandered aimlessly

about the clubhouse. There was not a soul there whom he knew; no

one who addressed a word to him Every one else seemed to be

having a good time, in their own way, with their own friends.

John Dudgeon got sick of it. He was a new member, and the

loneliness choked him. He caught up his cap and set out to walk

to the station, although he had an hour or so, to spare.

"A million pounds and misery!" he said to himself as he turned out of the avenue. "A million pounds!"

He walked along the narrow lane, between the high hedges wreathed with honeysuckle and dog roses, heavy-footed, heavy- hearted. The perfume of the flowers in the hayfields faded to soothe him. He was not even conscious of it. He only knew that he was very unhappy, very lonely, weary of his daily life, weary of looking forward into a hopeless future. Then, without a moment's warning, came his adventure. It wasn't much of an affair, but it took its place in his life. A girl had been accosted by a tramp. The spot was a desolate one and the man penniless. The girl was already feeling for her purse with trembling fingers when John Dudgeon came hurrying round the corner. She turned her white face towards him, and gave a half-stifled cry. John Dudgeon came hurrying on and the tramp, after a glance at his broad shoulders sheered off.

"Please don't worry about him," the girl begged, seeing the light of battle in her rescuer's eye. "I'd much rather—you stayed with me."

She was going to the station—so was John Dudgeon. They walked together, travelled up to Waterloo together, and she very speedily recovered her spirits and her tongue. She was a timid, somewhat childish little thing for her years—barely 19—pretty, in an ordinary sort of way; of limited intelligence, perhaps, but cheerful and talkative. To her John Dudgeon seemed quite a hero. He was one of the gentlemen at the golf club, too—quite a superior race of beings to the young men of her acquaintance, although there was nothing about his speech or manner to suggest any difference in station. They got quite confidential on the journey up to town, sitting in a third- class carriage, providently empty. She was an orphan she told him, and divided her time between an aunt who lived in a cottage near Walton and another in London. She was employed in a draper's shop—would like a situation in London, but her aunt was against it. Just now she was resting, recovering from an illness. The doctor had insisted upon a month's holiday. She found it dull at Walton all day long, and varied the monotony by going to town as often as she could afford it to see her other aunt. So she chattered on, telling him her whole history, and to him the years fell away. With a scarcely noticeable effort of memory he brushed them on one side. He ignored the miracle which had transformed his life. He was a clerk in the office of a music hall agent. His work was irregular, but he earned a good, salary. He had no relatives that he knew of, and plenty of time to spare. He hoped that he would see her again. Naturally, he did!

JOHN DUDGEON travelled backwards and forwards to Walton many

times during the next few weeks—but he never touched a golf

club. They walked together along the river bank, in the woods,

across the meadows. A late but glorious spring seemed to have

turned these low-lying lands into a paradise of perfume, and

blossom, and music. The meadows were yellow with early cowslips,

starred with buttercups. The woods were carpeted with primroses.

The river was soft and blue, as though summer itself had come.

Life had dealt him so many blows during the last few years that

he accepted this, her one favour, with a grim determination to

count it as a just recompense, due to him, to be seized and made

the most of. His self-respect was recreated. She watched for him,

listened to his lovemaking with shy pleasure, suffered his touch

with joy, looked at him with all the mysterious happiness of the

woman who sees her master to be. And John Dudgeon played the game

up to the last lap—and failed. It was a little habit of

his. He held her in his arms for one moment only—then he

thrust her away.

"Mary," he aid. "I am a blackguard!"

The change her face was a tragedy in itself. John Dudgeon's voice was hoarse, and he was ashamed.

"I am married," he said. "I am very fond of you, Mary. I am always lonely and very unhappy, but none the less, I am married."

She drew away from him, shivering.

"You—never told me! she murmured.

"Listen," he begged her. "Four years ago I was exactly what I described myself to you. I was a clerk employed by a music hall agent. I earned a moderate salary. I was independent. I was contented, almost happy. I had friends, as many as I wanted. It was four years ago!

"And now?" she faltered.

"It was in all the papers," he went on. "They called it the marvellous good fortune of a clerk. An uncle whom I had scarcely ever heard of died in Philadelphia and left me a million pounds. I only just knew his name. He left England when I was a child. He made it all mining. The papers called it a romance. I sat in my office one morning, making out a salary list for a small hall down in Southwark, and a lawyer came in. He put his silk hat on my desk and he turned to me. 'Mr. John Dudgeon?' he asked. 'That's my name,' I answered. 'I congratulate you,' he said, shaking me by the hand. 'You look strong enough—can you stand a shock?' 'If it's good news I can,' I told him. 'It's a million pounds,' he answered, solemnly."

"A million pounds!" she moaned, looking at him round-eyed, wondering. "It be-longs to you—all that money?"

He nodded gloomily.

"There was no doubt about it," he answered. "The lawyer thought to do me a good turn, and he took me about I got introduced to people, and I found that the world was full of ladies and gentlemen who wanted to make friends with a million pounds. I found a very beautiful woman. I thought that she was the most beautiful woman on God's earth, and I loved her, and I married her: and she loved—and she married—my million pounds! It wasn't likely to turn out well. She was a lady, brought up differently—different friends, different manners, different way of looking at things. But I don't think she ought to have done it. She doesn't want me now. She's got her house and her yacht and a little place in Scotland, and two hundred thousand pounds settled upon her. She has any amount of friends, but I haven't one. I have never been so lonely in my life. Mary, until you came."

"Oh. John!" she murmured.

"I mean it," he continued with a note of pent-up savagery in his tone. "I am a stranger in my own house and in the houses of her friends. I am a stranger in the whole world where she moves. The people who visit her and whom she visits tolerate me. The servants—hang them all—smile insolently even when they obey my orders. They know. I am there, but I don't belong! I wasn't born to it or educated to it. Their ways aren't my ways, and though I've tried hard I can't change. I tell you, Mary, there's no one crueller in this world than servants to a master whom they don't respect."

She was already beginning to forget herself. She was troubled with very little imagination, but his words were illuminating. Dimly she began to understand the suffering of which he spoke.

"Poor John!" she said, and this time all the old affection had returned to her voice.

"It's my own fault," he declared gloomily. "I ought to have known better. I made the mistake myself, and I most pay. But, Mary, I am sorry—I can't tell you how sorry I am—and ashamed!"

Once more her thoughts swung back to herself. The prospect terrified her. No more of these walks. A sudden end to the world of tremulous bliss into which John Dudgeon had led her. She clung to his arm, and her eyes sought his pleadingly.

"John," she declared, "I can't let you go! I can't! I won't! Let us forget what you have told me. Let us be friends, and I shall believe that it was all a dream."

"A dream!" he muttered.

Then he looked through the trees of the wood in which they were sitting, across the patchwork of meadowland, of river, and tree-belted slopes—he looked back towards the great city. He thought of his fine house, his motor cars, his investments, his bank balance and he groaned. He looked farther back still. He thought of that stuffy little office, with its odd flavour of patchouli and stale cigarette smoke, his luncheon—a ham sandwich and a glass of bitter, his cheap Virginian cigarettes, his steamboat and 'bus rides, his week's holiday at Margate, and he groaned again.

"A dream!" he muttered. "I wish to heaven it was!"

They walked out of the wood through a field of buttercups. Above the sky was blue, with tiny flecks of white cloud. The birds were singing. The air was sweet with perfumes. A gaily coloured butter-fly danced before them, as though to show the way to happiness. She drew closer to his side. Her hand gripped his. She was afraid of that far-away look in his face.

"We will forget," she whispered. "For a little time we will forget! I cannot let you go, John!"

SO they drifted to the very edge. He had nothing to conceal

now, and he used so of the resources of his great wealth for her

pleasure. He took her out in his motor car, long excursions

sometimes to different places, showed her the sea, the old-world

cities and villages which he had heard of all her life. He took

her about in London, but she would accept little in the way of

presents from him and their inclinations kept them both from the

fashionable places. Sometimes, however, they, lunched at one of

the lesser-known restaurants and more than once, when she was

able to stay with her aunt in town, they went to a theatre, in

cheap seats and morning clothes, and John Dudgeon thought that he

had never enjoyed the play so much. Once his wife was there, in a

box with a party of friends; and he pointed her out to his

companion. She drew a little breath. Mrs. Dudgeon—how she

hated her name!—was wearing a wonderful white satin dress.

Her hair was coiffeured in the latest fashion. Her neck and bosom

were ablaze with jewels. And beyond everything, she was an

exceedingly beautiful and well-bred woman, looking her best.

"Your wife," Mary whispered in an awed undertone, "and you care for me!"

He laughed. The canker was still there, but there was sorrow in his fixed eyes and bitterness in his laugh.

"I cared for her—once," he admitted. "It was about the time when she fell in love with my million pounds!"

"She is very beautiful," the girl murmured, "but she must be very cruel—very cruel and very cold. I think that she looks like that."

They spoke no more of her, but the evening was spoilt. Nevertheless there were others over which no cloud rested, and the change in John Dudgeon became a noticeable thing. The club saw little of him. He had quite given up the habit which had annoyed his wife so much, of mooing about the house. So they went on till the time of battle came.

IT was his wife who lit the torch. They came face to face with

her one day, and John, for once equal to the occasion, met her

insolent stare with stern immobility. She was in her electric

landauette, on her way to Ranelagh, and they were just returning

in his big touring car from a morning in the country. He showed

no sign of his knowledge of her, but, nevertheless, her faint,

contemptuous smile maddened him. For the first time he pressed

Mary to stop in town to dinner, and engaged a private room at the

restaurant which they frequented. Already the poison of that

smile was working!

Mrs. John Dudgeon visited her husband that evening in his room as he was changing for dinner. He has sent her a message which he knew would mean war.

"Do I understand," she asked, "that you are not dining at home this evening, John?"

"I thought that my message was plain enough," he answered, bending toward the looking glass to arrange his tie.

"You have forgotten, perhaps, that we are entertaining friends?" she remarked.

"You may be," he answered. "There is no friend of, mine who sets foot within these doors."

She raised her eyebrows. It was unusual to hear him speak thus. There was a decision in his tone, too, to which she was not accustomed.

"Whether they are your friends or mine," she continued, "the fact remains that we are giving a dinner party."

"Give it, by all means," he answered shortly. "I wasn't consulted. I didn't desire to be consulted. I have made other plans for this evening."

"They include, I presume," she remarked, with chill anger, "the entertainment of the young person who was with you this afternoon?"

"Whatever or whoever they include remains my business and mine alone," he declared.

She turned away with an expression of despair, mingled with scorn.

"You are too hopelessly bourgeois John," she said. "If you show yourself about with some little chit from a milliner's shop, you might at least dress her properly. You can afford it."

He turned around with a glint of passion in his eyes. Nevertheless, his restraint was admirable.

"It is only in the society to which you belong," he answered, "that girls accept such presents from their men friends!"

THE echoes of her laugh as she closed the door behind her rang

in his ears, a hateful thing. It rang in his ears as he stood on

his doorstep, waiting for a taxi—even after he had met

Mary, and was sitting at the table with her, waiting for the

service of dinner. She was wearing a new hat that evening, a

cheap little thing, but to him it seemed perfect. There was an

unusual colour in her cheeks, too—the long motor ride had

agreed with her.

"I think that this is just lovely," she said, looking around the stuffy, ill-furnished room as though it had been a chamber in a palace. "John, why didn't we ever think of this before? And I needn't go back till the 11 o'clock train. Isn't it delightful?"

He laughed a little recklessly. "Why not? It was the way of all the world—expected of him—justifiable in a hundred devilish ways. They drank champagne. Even Mary, and she was very inexperienced indeed was conscious of something different in the atmosphere, something electric, the presage of storm. She drew away from his first embrace, but it was only a momentary hesitation. She was afraid and yet she was conscious that there was nothing else in the world so delightful as this new intimacy into which they seemed to be drawn.

"John," she murmured, "It is close in here! Don't you feel it? I am stifled!"

He threw open the window. The room was at the back of the restaurant, the street below a retired one. The roar of London came to them muffled, almost musical. They sat there while the waiter cleared the table, John fighting his battle with grim courage, she utterly content, utterly happy, absolutely trustful. With the disappearance of the waiter they drew further back into the room, and she came naturally enough into his aims. He kissed her once, and then, drawing away, turned to pour out the coffee.

"Where would you like to go to?" he asked. "The Palace is quite near."

She struggled to conceal her disappointment.

"Must we go out?" she asked. "I thought it would be so cosy here for a little time."

He shook his head.

"They will want the room," he said. "They probably have other people coming. One is not supposed to stay at these places after dinner. Shall we try the Palace? Very good show there, I believe."

"Just as you like," she answered indifferently, turning toward the looking glass, to hide the tears in her eyes.

Out in the street she clung closer to his arm.

"You are not cross with me, John?" she asked timidly.

He gave her fingers a squeeze.

"Of course not, dear," he replied. "Why should I be?"

"And you are not tired of being alone with me?"

"If we were not in Shaftesbury avenue," he declared. "I should kiss you."

"I think I am sorry that we are in Shaftesbury avenue," she murmured.

THAT night his farewell seemed to her a little more earnest

than usual. He watched the train out of sight, and he walked all

the way home from Waterloo to Park lane. Side by side, as it

were, with his misery, he felt a peculiar exaltation, the

unrecognisable yet very real exaltation, of renunciation. The way

to happiness had been shown to him clearly, a happiness which

would have satisfied him utterly, which would have thrilled

through every fibre of his body. For her sake he had set his

teeth and clenched his hands and let it go by. Would she ever

understand, he wandered? Would she ever think of him as anything

but a fool? Then he turned into Piccadilly. It was close on

midnight. He was jostled and pushed from side to side. He had no

more doubts!

He appeared, the next morning in his riding clothes. His wife smiled as she saw him.

"I thought you had quite given up your efforts in that direction," she remarked.

"I am beginning again," he answered. "By-the-by, when do you go to Cowes?"

"To-morrow," she said, with a sudden alarm. "You weren't thinking of coming, by any chance?"

"Not unless you wanted me," he replied, with a gleam of hope. After all, anything would be better than a relapse into that hideous loneliness!

"To be quite truthful, I don't," she answered. "You'd only be bored to death, I wouldn't thing of it, if I were you; especially as the people who are coming are just the people you don't get on with. Why don't you go to Scarborough or the Isle of Man for a week or so?"

He turned quickly away. What a fool, after all these years, not to have known!

"I might do that," he assented. "It's getting too hot for town."

AT the telephone, half an hour later. Mrs. Dudgeon was telling

her dearest friend of the escape they had had. She sat in a low

chair, with the instrument on a small table by her side, where it

was, almost hidden among the blossoms of a great bunch of red

roses. She was looking very dainty and beautiful in her morning

wrap, a creation of flimsy lace drawn over a foundation of rose-

coloured silk. No wonder that John had been unable to turn away

from her without that little pang of smothered regret.

"Yes, is that Lena?" she said. "How are you dear? I just rang up to tell you about John. Such a narrow escape! I quite thought that he meant coming to-morrow, and you know how difficult it is. Yes, yes! Of course—but you don't understand. One can't say outright that he is not wanted, and he is so thick sometimes. Oh, of course, I might have done if it had been absolutely necessary! Victor put his foot down this time, and declared that he wouldn't come if John was going to be there to play host. Lonely? Oh, I suppose he has his own amusements! I never ask him any questions. What's that, Lena? I can't hear a word you say. Some one is making such a noise in the hall. Wait a moment while I see what it, is."

Mrs. Dudgeon turned toward the open door with the receiver in her hand. The expression in her face changed from one of petulant irritation to blank amazement. What was the meaning of these men—the policemen—their shuffling footsteps? What were they carrying? She dropped the receiver with a crash and sprang to her feet. They saw her then, and the doctor, who had followed in the rear of the little procession, and was now upon his knees, held out his hand.

"Keep her away, some one!" he ordered.

The butler came towards her. His face was white and his voice shook.

"Madam," he said, "we thought you were upstairs. It is the master—there has been an accident."

"Is he hurt?" she faltered.

No one answered her at all—a gloomy, tragical silence. She gave a low cry and fainted....

THE editor was standing in very much the same place when the

news reached the club. The youthful journalist brought it, as was

only fitting.

"Heard about poor Dudgeon?" he exclaimed directly he entered the room.

No one had heard anything.

"Thrown from his horse and killed in the park this morning. Fell on his head, and died within a few seconds."

A little thrill of sympathy found for itself various forms of expression among the group.

"Poor chap!" the editor said thoughtfully. "After all, he's cheated you fellows. He has gone and taken his story with him."