RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

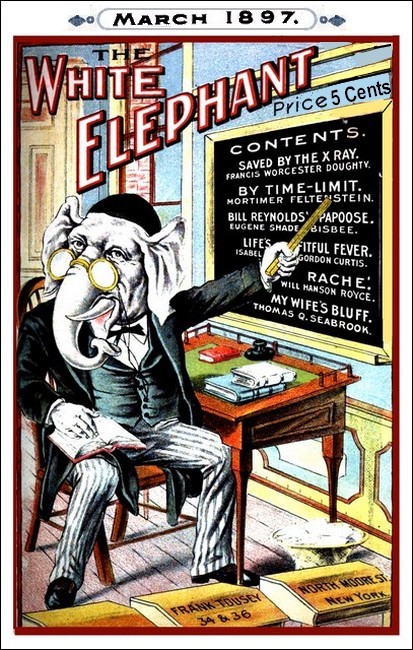

The White Elephant, March 1897 with "Bill Reynolds' Papoose"

OY WILMOT REYNOLDS was his name in full, but upon coming to Wyoming and joining the boys of the "S wrench" outfit, he had dropped the first entirely, and cut the other two down to plain Bill Reynolds. He was a strapping big fellow; but one glance at the fair skin, untouched as yet by prairie winds, told of the "tenderfoot," and the boys were all ready for their laugh when he tried his pony. Every new man is tested as to his horsemanship by being given the most vicious horse to ride that the boys' devilish ingenuity can secure, and—well, if he sticks to the one they pick out, he may congratulate himself upon instant recognition in the higher circles of "cowboydom," for your genuine cowboy dearly loves a good rider.

There were about twenty of us in and about the corral to see Bill tackle his pony on the morning after he came up from Rawlins with Bob Martin, our foreman. It was a small, wiry, black mare that had never known a rope or a brand, and while two of the boys choked her up to the "snubbing-post," two more blindfolded and saddled her. Her heels fairly twinkled as they flew out in her violent objection to the double cinch. But this sort of thing was an every-day matter, and she was soon in shape, and Reynolds beside her, as they led her out onto the open prairie, where there was plenty of room. Before any of us fairly realized it, he was on her back, and had reached over and snatched the handkerchief from her eyes. She made a pretty fight, and the boys howled and turned their guns loose, but never for a moment did Reynolds lose his grip on her, and the victory of mind over matter was a question of some twenty minutes, and the man was master—for the time being. Not until later did we learn that Bill was an expert polo rider.

From that hour Bill Reynolds was a popular man, and as he threw the saddle off the animal he had conquered, one of the boys pulled a bottle from his pocket, and stalking up to him, said: "Well, old boy, you did well; let's irrigate."

Reynolds raised his hand and smilingly warded it off with: "Thanks, my friend, but you'll have to excuse me; I came out here on account of that," and his way of saying it made him look a foot taller in the eyes of every man there.

"No harm, Bill," said the man who had proffered the whiskey.

"And none done, Wilson," replied Bill, holding out his hand, which the other gripped.

After that, if you wanted to find Wilson, you had only to look for Bill Reynolds, and vice versa. And they made a great team, both over six feet, and carrying around two hundred pounds of bone and steely muscle.

Twelve of us, including Wilson, Bill and myself, were told off to round up the foothills of the Wind River Range, and we left the crowd, who were going down the Sweetwater, at Independence Rock. This wasn't very many years ago, but nevertheless, a railway had not been dreamed of, even as far as Deadwood, and we were many a long mile from there, with Sioux to the North and East, and Shoshones to the West. Reservation restrictions were not as rigid then as now, and we had as much trouble with Indian cattle thieves as the storms and coyotes gave us. There was no open danger, but then there is always danger in the air an Indian breathes with a white man, and we kept a sharp lookout for marauders.

"Buck" Adams and I doubled up, and of course Bill Reynolds shared blankets with Joe Wilson. Bill had managed to make Mike, the cook, think he had room in the wagon for a banjo, and we used to sit around the fire after supper and listen to him play. Bill was none of your ready-made players, such as may be heard in any country town, but a finished artist, and he brought music from those strings such as none of us, who had only heard the regulation ranch twang, ever dreamed lay dormant in them. He sang in a full, rounded baritone voice, and from a seemingly inexhaustible repertoire. He seemed happy in a superficial sort of way, but there was an undercurrent of sadness in everything he did when not in the saddle, and I daresay I was not alone in wondering where he came from, and what brought him out here, so far from his natural environment. Aside from his words on the day Wilson offered him the drink, I could think of nothing that could have driven him from home and friends to find a new life among a wild lot on the frontier. But then, men in our line are not usually gifted with fine perceptions, or great subtlety of speculative power. I do not think the others noticed this peculiarity in Bill as much as I did, but then, I had been an Eastern man myself, until—but I am telling Bill's story now, not mine.

We had had pretty good luck, and had got about four thousand head together, and were headed back toward the Sweetwater; we had not seen the first sign of an Indian, when one night we were camped on the south side of the Wind River Range in as pretty a natural park as ever the eye of man beheld. A stream, icy cold, and clear as purest crystal, flowed through it on its way to the river, game swarmed about us, and we had only to cut a willow and go to the creek for all the trout we wanted. The cattle were scattered over the valley, ranging two or three miles from camp, and Bill and I were to do night herd. So after supper, we saddled up and cantered off. The nights were rather fresh, and the cattle showed not much inclination to wander. We rode slowly around them, driving in stray ones here and there, each going in opposite directions, and passing each other at nearly the same point every time in the circle of about two miles circumference. The night was starlight ami almost cloudless, and I could occasionally see Bill on the opposite side of the herd. The Great Dipper had turned topsy-turvy, and I knew the dawn was not far away. Presently Bill came along, and pulling up, asked me for a match. I gave him one, and he was holding the flame to his pipe, when a series of demoniac yells rent the calm night air, and old as I was at the business, I felt my scalp creep, for well did I know the portent of that sound. We were stampeded by Indians, and before the match fell from Bill's hand, the yells were augmented by the crack of fire-arms, and that vast throng of cattle rose as one, and transformed by unreasoning fear into so many mad things, plunged headlong into the night.

The roar of Niagara, if brought side by side with that mighty tread, could never have been distinguished. There was but one thing to be done, and that is what we call "milling"—that is to turn the head of the stampede, and start them going round and round in a constantly decreasing circle, until they gradually quiet down, and, leaning close to Bill, I yelled in his ear, and we started after them side by side. They had taken a course right out over the open prairie, thus saving the wagon from destruction, but the rear passed very near it, and as we rode furiously along in our attempts to overtake and turn the leaders, we heard a volley of shots from the direction of camp. We had run our wild race a half dozen miles before we finally got them turned and circling, and only then by killing a score in the lead; but the "mill" began to do its work at last, and presently they came to a dead stop and looked at each other, as if to inquire what it was all about. The boys from camp soon began to come along, and "Buck" Adams and Wilson were the first to show up.

"We got four of 'em, boys!" cried "Buck," as he got within hailing distance.

"Yes, and one's a squaw," added Wilson; "there were only eight or ten of 'em, an' the rest lit out for the hills; guess they hadn't calculated on the wagon bein' a feature of the show; you boys have had enough for one night I reckon, ain't you? Better go on back to camp now; 'Buck' and me'll take hold."

Accordingly, Bill and I rode back in the gray of dawn and found their words true. Four dead Indians lay within a few yards of each other on the open ground where they had fallen, and while I stood by the newly made fire, Bill wandered off toward the bodies. It was all new to Bill. He had not been gone long when he came back with something in his arms, and stopping in front of me, held it toward me. As I live, the man had a papoose in his arms, and a live one at that! It was bundled up in regulation Indian style, and its black eyes danced and sparkled as they regarded me wonderingly. Not a sound did it utter—I never yet heard an Indian baby cry; that seems to be an accomplishment only vouchsafed to civilization.

"Where'd you get him?" I asked.

"Found him strapped to his dead mother's back," he replied.

"And what on earth are you going to do with him?" I managed to ask.

"Keep him, I suppose; there's nothing else to be done."

Bill's voice, always so cheery, had the sound of an ache in it as he held the waif in his arms before the fire on that chill October morning. Its unconscious misery had struck the tender chord in his nature, showing to all of us the real man. His unspoken sympathy made itself felt by every one of us, and in an hour after the stampede, there was not a man in the crowd who would not have died fighting for the helpless little savage whom Providence had cast amongst us. Bill cut him loose from the board to which he was fastened, and wrapped him up in his blanket. Then he got his horse and rode away. He was gone about half an hour, and there was a trace of a smile on his face as he came up with a canteen and poured its contents into the tin cup hanging at his side.

"I had to throw her and tie her up to get it," he explained, "but the kid's got to have milk;" and the roar that greeted his efforts when he tried to make the little thing drink, awoke the echoes in the surrounding mountains.

"Why, Bill, how old do you think that kid is?" asked one of the boys.

"Look at that row of teeth!" cried another. "Haven't an idea," answered Reynolds, looking up. "Well, he's over two-year old," said some one, "Give him a piece of 'jerked' beef, and see him eat it; that kid don't want no milk."

Hereupon, Mike gave him a piece of smoking hot venison. He reached and took it in great solemnity, and began to chew away on it for dear life.

After awhile he got up and toddled around, eying things curiously, but seemed to soon feel quite at home, and conducted himself much after the fashion of his civilized kindred; all save by crying; he never cried. He became everybody's pet, and Bill actually cut a blanket in half and made him a funny little pair of trousers and a shirt. We carried him along with us in the cook wagon back to the ranch, and although he was the admitted friend of all, yet he evinced a special fondness for Bill, and was known far and wide as "Bill's Papoose."

We had been back to the home ranch about a week; the baby had

been installed as the mascot, when Martin interrupted the

monotony of ranch life by announcing that one of the owners and a

party of friends from the East, would be up the next day. We were

two days' drive from the railroad, and were accustomed to these

visits several times during the year; so along in the afternoon

of the following day the party came; old man Barker, from Denver,

and his daughter, and two Cheyenne cattle men and a Mr. Riverton,

of New York, and his daughter. Barker had built a big, single

floor house not far from the ranch house, where he used to

sometimes bring his family and spend a part of the summer, and

there the whole party was now quartered.

"Little Bill" had the run of the whole place and used to toddle about everywhere. He soon began to talk in that peculiarly disconnected way of babies, and had forgotten all the Sioux he ever had heard. He was just like any other baby, always in mischief, and forever getting into scrapes; a quaint little figure in blanket suit of bright scarlet, and tiny, moccasin-clad feet. I daresay he would have been called picturesque anywhere else, but we never thought of that—cow-punchers have the sentimental bump rather poorly developed.

He had been over to the cottage all the morning of the day following the arrival of the visitors, and about noon he came toddling across the open, and I went to meet him and carry him in. As I picked him up I noticed a small gold chain about his neck, and taking hold of it, saw that it secured a locket. Curious to sec what they had given him, I opened it, and looked upon a very fine portrait of one of the young ladies of the party—the one I supposed to be Miss Riverton.

Bill was standing in the open doorway as I came up, and I showed him the locket and its picture. As he looked upon the face his own turned white as death, but he held it in his hand for a moment, his fingers trembling strangely; then he stuffed it into the baby's neck, and without a word, turned and walked across the floor to his bunk. I could not think of anything to say, so I put the little one on the ground and turned toward the corral to think it over. There was a mystery here. Was this, then, why Bill had come West? I hadn't long to think, for the baby came out, and Bill was right behind him.

"Take care of the young one, will you, Jack? I'm going away for awhile," said Bill, and passed on toward a pony tied nearby.

As he mounted and rode away I turned toward the child, who was looking wistfully after him, and observed a small bit of paper dangling from the chain about his neck. Closer inspection showed it to be a letter, and it was addressed to "Miss Mildred Riverton."

This discovery made clear what Bill had meant by asking me to take care of the baby, and tossing the little letter carrier onto my shoulder, I made my way toward the cottage. I felt a strange delicacy about anyone seeing even the outside of this letter, that was, I felt, intended for her eyes alone, and was more than glad to find the original of the miniature sitting alone on the porch.

I set the baby down and said: "A message for Miss Riverton," and as she rose the little savage ran toward her as fast as his chubby legs would carry him, and she caught him in her arms with a rare, musical laugh, and then read the note.

Her face grew paler than had Bill's when he looked at her portrait, and I thought she was going to fall, and stepped toward her, but she quickly recovered herself—this fragile Eastern girl— and in a steady voice, said: "You are a friend of his, are you not?"

I assured her that Bill, for it was he whom I knew she meant, had none but friends in our camp.

"Then you must go to him at once!" she cried, subdued excitement in her tones; "he is in great danger—he has ridden away to destroy himself—ah, baby!" she vehemently cried, and snatching the marveling child to her arms, she pressed him close against her breast and covered the little brown neck with burning kisses, tears the while coursing down her cheeks.

Bill was in danger! I needed no second admonition, but ere the words had died from her lips, was flying across toward the corral. Briefly explaining to several of the boys that Bill was in trouble and had gone away to perhaps make an end of himself, in five minutes six well-mounted men rode out on the open prairie, and striking the trail, broke into a run after the man who was running away from his friends. The trail was easy to follow through the sage-brush, and from its appearance he had evidently been going at a pretty sharp clip, so we increased our own gait, and in the course of half an hour were five or six miles away, and had not yet caught a sight of Bill. Straight ahead of us was a deep arroyo, and the trail led directly toward it.

Every man among us knew it, and that there was no crossing nearer than three miles lower down. Was it possible, I wondered, that Bill had jumped it? Not a man of us would have dared try it, and yet the trail led on straight as an arrow. Suddenly a horrible thought came into my mind, but I had not time to give it rein when we came to the edge of the arroyo and looked down, and the question that had half formed itself, beheld its answer. There, at the bottom, thirty feet below us, lay Bill and his horse. The latter was stone dead. In much less time than any pen can picture it, three lariats were dangling over the side, and three men knelt beside their comrade. I put my ear to his heart and heard a faint thump—thump—the sweetest music that ever came to my ears. We swung a lariat about him, and a moment later he lay on the ground above, but as he was drawn up, I saw his left leg dangle limply, and at once divined the cause. True enough, it was a compound fracture of the thigh.

Well, we got him home, and he did not recover consciousness until he heard old man Barker saying to bring him right over to the house, but he was strong enough to protest so vigorously, insisting that he preferred his own bunk, that we took him where he wished. I had had some little surgical experience in an earlier portion of my career, and managed to set the leg and bandage it up pretty comfortably. Of course, the pain must have been awful, but Bill never winked, and save for his pallor, you never would have known there was aught the matter with him. Just before sunset, Mr. Riverton and his daughter came over, and asked if they could see Bill.

I carried him the message, and he simply turned his head wearily toward the wall, and said: "Ask them to come in." The two entered the big room.

There was no one else there, and as Miss Riverton caught sight of the form on the bunk, she gave a little cry, and running toward him, dropped to her knees, and flinging her arms across his body, buried her face in them and shook with sobs.

I discreetly withdrew.

As I passed into the open air, a piece of paper lay at my feet, and picking it up, I began to mechanically read some lines written on it, but my mind was wholly upon the scene I had just witnessed. Finally, however, the words burnt their meaning upon my brain; I had become the unintentional possessor of their secret, for the note was the one Bill had sent by the baby, and read:

For the sake of our old love, Mildred, take this poor baby and educate him— the boys here know his brief story. I am going away, and this time forever out of your sight, for the pain of knowing you, who loved me as I once was, to be lost to me for all time, is more than even my courage can face. I read of your engagement in a New York letter to a Chicago paper months ago, and Mildred, your lover who was, wishes you joy unbounded, for a dying man can afford to be magnanimous, and if you are not already married to my old acquaintance, Tom Arthur, I hope you soon will be.

Don't bother about me, Mildred; I did it all myself, and perhaps deserve my fate, but the bitter irony of it is the part that chokes. If you care to know it, I have not tasted the stuff that cursed me and dragged me down until even woman's love could not lift me up, since the night I left you with that oath on my lips that I had taken my last drink.

There are some papers of value—mining claim deeds and the like—in my box, that I wish you would take care of for 'Little Bill,' as they call him. That is all, but thank God, I go to my last sleep with lips unstained and my soul clear. Good-bye, Mildred, and God bless you.

Roy.

IN a little while Mr. Riverton took his daughter away, and I went

back to see Bill. The color had returned to his face, a smile

haunted the corners of his mouth. I held the note in one hand, a

match in the other. Holding the paper before his eyes, I said:

"She dropped it, Bill, and I didn't know what it was until I had

read it; I was thinking of something else; no one else shall see

it."

I struck the match and as the paper flamed up, Bill reached my hand and held it tight, as he said: "God bless you, Jack!"

I returned the pressure and the wish—it was in my heart just then.

Bill looked me steadily in the eye for a moment; he seemed to want something, but before I could ask him what, he said: "Sit down here, Jack, I owe you something; I thought it was a curse for bringing me back, but since she came, it has taken the form of a blessing. Jack, we were engaged to be married; fortune was kind to us both; her gifts were lavish, and happiness lighted our pathway. But the set I lived in ran a fast gait, Jack, and before I knew it I was the leader in the race down hill, while she was concealing behind a mask, an aching, breaking heart. She gave me chances, times innumerable, to break away from the life I led and be a man for both our sakes. But the passion was stronger than love, my boy, and held me in heaviest chains. One night I went to her house drunk, Jack. She saw it instantly, and in that instant a look came into her face that sobered me; it was between a yearning, passionate love for the soul of Roy Reynolds, and a shrinking loathing for the physical beast. I turned to leave her, then came back for a moment, while I said: 'Mildred, I've touched the last drop of liquor!' Before she could reply I was gone, but I heard her cry 'Roy' as the door closed. That was two years ago, Jack, and I've kept my word; but, my boy, don't think I'm a hero, for the shock of her look that awful night drove all desire out of me, and the very smell of the stuff now nauseates me. I thought she was married and that left me small desire to live; besides, I just couldn't see her again, Jack; it was too much! But she's been waiting and looking for me, Tack, and we are going away and we'll take care of 'Little Bill together. And that's why I say 'God bless you, Jack!'"

I wrung his hand in silence and left him alone in his new happiness.

* * * * *

IN a week it was thought Bill could be moved, and of course he could get better attention on the railroad than away up in the country, and so an old Government ambulance was resurrected, and a good bed made for him, and he looked mighty contended for a man who had had his leg-bone stuck clean through the flesh. The different conveyances of the party got in line, and, as they moved off on their long drive, the ambulance bringing up the rear, the last the boys saw of Bill Reynolds, he was lying with his head in Miss Riverton's lap, smiling a farewell to us all while, standing at their side, waving a handkerchief in his little hand, his chubby, brown features a mixture of wonder and regret was "Bill Reynolds' Papoose."