RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Professor Appleton, the famous scientist who journeyed through space from the Earth to Mars in his wonderful Marsobus, accompanied by

Teddy Craig, a schoolboy, Mackenzie, a Scottish engineer, and Ashby, a hardened globetrotter, in making the attempted return to Earth finds that a mysterious planet, which has puzzled him from his observations from Mars, is in his trajectory, and he determines to explore this strange body. The planet, he finds is a kind of water world where giant fish disport themselves in the depths and queer people with shining fish-like garb cruise in vessels of great size. Ashby, horrified by the appearance of the denizens of the deep, has a nervous breakdown and has to be tied down, but the remainder of the part, anxious to investigate, are captured by the people of the boats, their downfall being brought about by the means of great nets.

PROFESSOR APPLETON, the man who had made the tremendous journey from Earth to Mars and was now on the way back, with Teddy Craig, Mackenzie the engineer, and Ashby the globe-trotter, in the wonderful machine called the Marsobus, looked through the windows of the craft, filled with various emotions, at the strange new world to which the Marsobus had come.

There was sufficient to give the adventurers cause for thought—serious thought. They had seen from afar off the wonder of a world that seemed to be nearly all water—a phenomenon for which Appleton, most famous of scientists, had been prepared as the result of his observation of the celestial body. True, they did not know what lay beyond the limits that they could see, any more than a man flying over mid-Atlantic would know that it was bordered by solid earth. But there was this difference, at any rate: Appleton's theory was that, with an atmosphere as dense as he had found that of this strange world to be, there was certainly a very disproportionate amount of water as compared with land-masses.

It was this phenomenon that had intrigued him to descend upon the planet, not with the intention of remaining there for any length of time, but in order to make some investigations regarding what had been a mystery to him ever since the time when, viewing the vast expanse of space from Mars, he had found some intervening body between Mars and the Earth—some body that not only cut off the sight of the tiny gleam that represented the Earth, but also interrupted the wireless communication that had been possible previously.

"Fellows," he said, after watching for a while the figures on the fairly large island, now growing more distinct, and the great ships that were lying off, "I think, after all, it would be best if we alighted on the water, and tried to get into touch with someone on one of the ships."

"A good idea, Chief," Teddy Craig said. "And I've got another!"

"Out with it," rapped Appleton.

"Something spectacular may help us," Craig told him. "We don't know what sort of people these are; and if we made a dive into the water and disappeared, only to come up to the surface again a little later, they might be impressed. What do you think?"

"A good idea, indeed!" Appleton agreed. And a swift manipulation of levers changed the direction of the Marsobus so that she dived for one of the many ships which were moving through the water, or lying in what was evidently a harbour. Most of these vessels were huge affairs, greater than any that the adventurers had ever seen. They possessed no funnels or masts. They were tall-sided and of great width, bow and stern being similar in construction, and the appearance of the Marsobus on the water was the signal for several of them to rush forward as if to ram her. Appleton was quick to act; he set the levers of the machine so that she rose vertically, escaping a collision only by the merest shade. Looking down upon the top of one of the ships thus robbed of their victims, the occupants of the Marsobus saw that it was crowded with moving figures, all staring up at the strange visitant, undoubtedly, as the binoculars allowed to be seen, in no small trepidation.

"That's the courage of fear," said Appleton grimly. "You see!"

By a touch of his lever he made the Marsobus dive, seemingly for the particular ship they were over; and there was a rush on the part of the figures which disappeared and left the deck clear.

"I don't think we've got much to fear, fellows," Appleton said. "We'll go down again now and submerge, and see what the effect is. Strange, isn't it—there seem to be no buildings on the land, except those down by the shore? It looks as though these people are water dwellers."

Suddenly he let the Marsobus descend vertically; she alighted on the water, well away from any ship, and before any one of them could attempt to attack her the submersing apparatus caused her to begin to sink beneath the surface—while Ashby and Craig, standing at the uncovered but watertight window, saw the astonishment of the people on the deck of the ships.

Then all this was blotted out, as the Marsobus disappeared into the depths.

"Light on, Chief," called out Mackenzie, and Appleton switched on the light. The "splash" of it in the water, as the Marsobus sank still lower, produced a weird effect, and scores of strange-looking fish went scurrying away before the unwonted vision presented to them; and some of the creatures were huge things, octopus-like, but larger than any octopus of which Appleton had ever heard.

Their appearance was sufficient to inspire something like astonishment into Teddy Craig at least, while Ashby gave vent to exclamations of terror.

"Heaven knows what they are!" he cried, trembling all over. "For mercy's sake, Chief, get away! It's horrible! I can't stand it!"

It was a revival of the nervousness that had overcome Ashby when Appleton had first suggested stopping on the water planet, and Appleton was afraid for him.

"It's all right, old chap!" he called out. "Those—those things are more scared of us than we need be of them. They can't hurt us in here! Look at 'em!"

There was no need for that injunction as far as Craig and Mackenzie were concerned, for they were watching intently the octopi scurrying away.

"Other weird creatures there were too, with long gleaming bodies as of fishes, with tails behind them, with fins that seemed to be out of proportion to their size, and, most striking of all, with heads which, following to the line of the body without plainly marked necks, were very animal-like in appearance except for the fact that, the ears were gill-like, and worked in keeping with the movements of the mouth that was set below a slightly protruding nose. The four fins of these strange creatures were like those of sea-lions, and the eyes set on each aide of the head were slit-shaped and covered with constantly moving lids. In fact, the combination suggested the sea-lion.

"Like a fairy-tale picture, Mac," Craig said. "It's rummy too!"

"Rummy's the word," Mackenzie agreed. "Sort of nightmare a fellow might have after too many rations of rum. Here, Ashby, old chap, pull yourself together!"

The man was still trembling and ashen-faced, and it was clear that he was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Appleton, alarmed, realized that it would be a mistake to prolong the ordeal unnecessarily, and touching the button that controlled the movable shutters, he so cut off the scene, except from the steering cabin where he himself was seated.

"Poor beggar!" he muttered. "Hope to goodness he's not going mentally groggy!"

As he thus ruminated he was working the Marsobus forward and not downward, so that it came to a sudden stop—with a crash and a grating which all knew meant that she had fouled some sunken rock.

Immediately Appleton ascended to the surface, intent on seeing if any damage had been done—a quite unlikely contingency because of the peculiar metal of which the Marsobus was made. He unslid the window-shutters, and the little party, peering across the water, saw that they were within a few hundred yards of the shore of the island that they had viewed from above.

They saw, too, that there were large numbers of the strange fish-like creatures swimming towards the land, on which were a crowd of people.

"What are we going to do, Chief?" Mackenzie asked. "Shove out the collapsible boat and—"

"I'm not going—I'm not going!" almost screamed Ashby, making a threatening rush at Appleton. There was a mad light in his eyes, and Mackenzie, fearing what he might do, grabbed hold of him. The next instant the pair were struggling fiercely on the floor of the central cabin, and Ashby, strong with the added strength of madness, fought ruthlessly. Mackenzie, however, was no weakling, and realizing that in his madness Ashby would have no mercy, the Scotsman exerted every effort to conquer him.

"Keep off!" Mackenzie gasped, as lying on his back, with Ashby over him, he saw Appleton approaching.

Next moment, with a sudden movement, Mackenzie had brought his knees up with a great force and struck Ashby in the body.

The frenzied man went flying across the saloon and crashed against a chest, falling to the floor and lying stunned.

"Poor beggar!" said Appleton again. "We shall have to do something for him. Let's put him in his bunk."

It took all of five minutes to get the unconscious man into his bunk, where he lay like a log.

"We don't know what's going to happen next," Appleton said. "And I think it would be wise to take precautions with him. I hate to do it—but I suggest we bind his wrists and ankles."

"I think you're right, Chief," Mackenzie agreed. And this, to them, very distasteful task was carried out.

"Now, we'll see what's happened to the bus!" the Professor exclaimed, and the trio gazed through the window.

Appleton turned the Marsobus about and drove her towards one of the great ships.

"They're as scared as mice, Chief!" Teddy Craig said excitedly. He had been looking through the window and had seen the hurried movements of the strange vessels that looked like floating houses the nearer they were approached. There was, however, no attempt this time to drive off the Marsobus, no movement to attack her, for which, naturally, the adventurers were not a little pleased.

"It's going to make our chances better and things much easier for us if they're afraid," Appleton said, as, with her remarkably constructed floats that automatically issued from the Marsobus when necessary, the machine rode on the water, and the Professor opened the door that gave exit. "We'll see what we can do to get into touch with someone."

The rope ladder was thrown out, and Appleton himself went out and stood on it and waved his arm towards the nearest of the ships. It was one of the largest, and, being only about thirty yards away, towered above the long tapering body of the Marsobus.

Appleton needed not to shout to attract attention, because the side of the ship, in which were a large number of port-holes, showed faces of people looking at the Marsobus. Strange faces they were, too. Bullet shaped, with large round eyes deeply set, and overhung by pendulous lids; a mouth that showed thick and red-lipped through a mass of hair, beneath which Appleton surmised ears must also lie hidden, since they were not to be seen. Such was the appearance of these folk who stared at what they must have considered to be the equally astonishing figures on the Marsobus.

They were curious, they were excited, and they were afraid these three facts were clear enough to Appleton who, for a moment or two, did not know what to do; he was afraid lest if he went over in the collapsible boat it would be the signal for hostile action to begin.

"We've got to take the risk, though," he said over his shoulder to Mackenzie and Craig, who were looking out of the top of the Marsobus. "Bring up the boat!"

It was done, and Appleton suggested that he and Craig should go over while Mackenzie remained behind, ready, if necessary, to take action with one of the guns.

"But don't do anything rash, Mac," he said; and the Scotsman grinned.

"I'll punch a hole right through that ship, mon," he said, "if they try any monkey tricks. They look now as though they might too!"

The appearance of the boat on the water, with Craig and Appleton in it, had changed the attitude of the people on the ship; they had rushed from the port-holes, which were covered now, and had gone on to the top deck, standing there in a dense mass and armed with long spears, each of these having two barbed points to them. For the first time the adventurers had their view of the full length of the people. Almost ape-like as they were about the head, their bodies were very different from those of apes. Indeed, they looked for all the world like fishes. They were arrayed in shining raiment that gave them the appearance of being clad in chain-mail. Appleton, however, quickly saw that this was not the case, that the clothing was, apparently, made from the skins of fishes. The effect was remarkable enough, indeed, for these people looked half men, half fish.

They carried, all of them, long sticks pointed at the end, each with two barbs; and these they were waving threateningly towards the Marsobus.

"They look like knights in armour!" Teddy Craig exclaimed. "Sort of King Arthur crowd! I lay, Chief, let's go ashore!"

"Right oh!" Appleton agreed. And a few moments later the rope ladder was let down, and the collapsible boat was launched. Into it the adventurers dropped, each armed with his automatic.

"Row, Teddy," Appleton said. And the boy pulled away from the Marsobus.

Appleton, sitting in the stern, saw the commotion that was caused amongst the crowd on the shore; they were evidently not at all pleased at the movements of these strangers, and suddenly after a brief and seemingly heated discussion they took action.

Scores of them raised their barbed spears and hurled them at the approaching boat, then no more than thirty yards away. Fortunately Appleton read the signs aright, and cried, as he slumped to the bottom of the boat:

"Get down!"

Craig obeyed, leaving the oars hanging in the rowlocks. Spears went hurtling over the frail craft, to fall into the water harmlessly. Several of them, however, found resting-places in the shell of the boat, and the holes that the barbs tore let in the water so rapidly that the vessel began to sink. At the same instant, although neither of the crouching pair saw it, the great ships were moving towards the Marsobus.

"We've got to go overboard, Teddy," Appleton said, as he saw the water rushing in. "Now!"

Together they went over and began to strike out for the Marsobus, where, as they saw, Mackenzie was standing at the gun, which was run out through the port-hole. Glancing behind him Appleton saw the reason for the engineer's action. He realized that Mackenzie was going to try to hold off the ships while he and Craig reached the safety of the Marsobus.

One shot only did Mackenzie fire at the ships behind the swimmers, and then, springing from the gun, he was at the door on top of the Marsobus, firing rapidly with his automatic.

"Hurry—for goodness' sake hurry!" he cried. "There's a sword-fish!"

The last word was sufficient to make the swimmers look hurriedly over their shoulders, and they saw indeed a grim monster slicing through the water after them, its vicious-looking "sword" flashing as it came. It was fewer than twenty yards away, and at the rate it was moving Mackenzie felt that there was little hope for his comrades unless he were lucky enough to get home a shot. It was no easy matter, especially as the Marsobus was rocking to the motion of the water, and as the people on the nearest ship were hurling more spears, thinking, no doubt, that they had their chance presented to them while the strange-looking individual on the queer vessel was so busily engaged in trying to save his companions' lives.

Nevertheless Mackenzie, not deigning to seek cover, continued to fire until his pistol was empty, almost moaning as he each time missed.

Appleton and Craig were swimming as they had not swum before, slicing through the water straight for the Marsobus, caring nothing for the spears that plonked into the water around them, their one anxiety being to escape the terror behind them.

Neck and neck they raced, urged on by Mackenzie, who in his frenzy to help was now swinging by the rope ladder.

"Come on!" he cried out, as Craig came within a few feet—Appleton, with fine courage, having eased up a little to enable the younger man to get to the ladder first. One final spurt, and Mackenzie had Teddy by the hand.

"Can—manage!" Craig gasped, realizing that after all it would be easier to act on his own, and Mackenzie let him alone.

Teddy grabbed the ladder and hauled himself up, and a moment later there came an agony-filled cry from Mackenzie. Teddy told him that Appleton had been caught, but he felt the ladder beneath him shake, glanced over his shoulder, and saw Appleton scrambling up the ladder, having reached it just in time to avoid the flashing sword of the monster.

"Get in, both of you!" cried Mackenzie. "Else those spears will—"

There was no need for him to finish the sentence. The three men dropped into the Marsobus, hauled in the ladder, shut the door just as a shower of spears came over, clinking on the shell of the machine.

Through the window they saw the swordfish dashing itself against the side of the Marsobus, but they knew that that could do no harm. Nevertheless, Mackenzie, angry at having missed it so badly before and having reloaded by now, fired again through the gun-port and succeeded in getting a couple of shots in the fish's body. The water was dyed red, the sword-fish lashed about furiously, then made one more dash, but never finished it. It died in the midst of its rush.

Now that the episode was over, the three men were trembling like children, and it was some time before they could gather themselves together. It was Appleton who recovered clear-headedness first, and he pointed a still shaking hand at the ship that was nearest the Marsobus.

"Mac!" he cried, "you holed her and—"

"I did, mon!" Mackenzie agreed, with a slight laugh. "I told you that I'd punch a hole clean through any that tried tricks. It stopped 'em coming, too. The moment that shell plonked in the whole bunch of them hove to, though they did throw in some more spears. But what are they doing now?"

This was signalized by considerable excitement being displayed by the people whom the adventurers could see at the port-holes of the ships. It was as though they were shouting their pleasure at having seen the creature killed, and Appleton said to Mackenzie: "Seems to me they're rather bucked about that shot of yours—I mean the one that killed the sword-fish. I vote we take advantage of that; it may make things a bit easier for us."

"You're boss—carry on!" Mackenzie said coolly.

"Well, we'll make another attempt when Teddy and I who look pretty dreadful figures, have changed. I'm chilled to the bone! Keep an eye on things while we change."

"Right oh, Chief!" Mackenzie said. And for the next half-hour he stood by the window looking at the vessels, which made no move to attack nor showed signs of going away. It was as though they were waiting for their strange visitants to make the next move; in fact, a few minutes before Appleton was ready there appeared on the deck of the ship that had been struck by the shell a man who waved his arms as if beckoning, though it was evident, that he was not altogether at ease. He had deliberately thrown aside the spear that he had been holding, and Appleton accepted that as a token of peace.

"We can't afford to risk our only other boat," Appleton said. "I suggest that we drive the bus towards the ship that man is on."

Mackenzie nodded, and went to set the engine working. Appleton steered the Marsobus slowly in the direction of the vessel, and the people who had been at the port-holes promptly disappeared. But the man on the deck, who had given what had been interpreted as an invitation, stood his place, even when the Marsobus came to rest alongside.

"Now, then, up we go—and keep your wits about you," Appleton said. "Pistols all right? Good! Keep 'em in evidence—they may be useful. Come on!"

Up on to the top of the Marsobus the three men went, and found the deck of the ship filled with men. The Marsobus lay many feet below the ship, and the top of it was on a level with the lowest row of port-holes. It was quite easy to see in; but, beyond a casual glance, none of the adventurers wasted time upon that. They were anxious to get to close quarters with the strangers who were leaning over the side of the vessel, gesticulating wildly and jabbering away in a tongue which, while naturally unintelligible, was clearly very simple—as far as Appleton could judge, and he was an adept at philology. They seemed to be getting more excited.

The man who had given the invitation to the adventurers was leaning over and indicating a fixed ladder on the side of the ship, and Appleton, greatly daring, said to his comrades:

"That's an invitation to us to go aboard. We'll do it. Keep your pistols in your hands, and let fly if there's the least sign of trouble!"

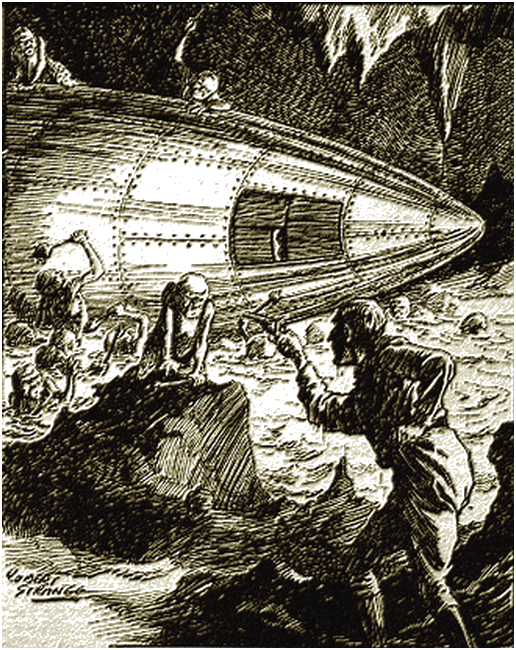

He climbed up the ladder, and the others followed him at once. As they reached the top the crowd drew back, and Appleton stepped on to the deck. Craig was immediately behind him, and Mackenzie came over the side just in time to see the rush that took place, and to be taken quite as much by surprise as the others had been.

Scores of the little men leapt forward and made for Appleton and Craig, while others jumped between the ship's side and Mackenzie, who found himself caught in the toils of a net that enveloped him and held him tighter the more he struggled.

Through the mesh of it he saw that an exactly similar thing had happened to his companions who by now were on the deck, struggling wildly, tearing at the nets. The suddenness of the attack had been complete, and the nets, thrown skilfully, not only enwrapped the unfortunate men, but rendered the use of their revolvers impossible. The situation looked desperate.

Craig lost his: knocked from his hand by the net. Appleton, although he still retained his, had no more chance than Mackenzie of using it, because one of the assailants sprawled upon his arm. Evidently the strangers realized that while their "captives" held these weapons they would he dangerous, and were bent on getting possession of them.

And Appleton's they got, after a while, that is. They succeeded in knocking it out of his hand, and it got mixed up in the folds of the net; thereby preventing a danger, not only to themselves, but also, as the Professor knew, to the enmeshed men.

They were not, then, without intelligence.

And the thing that Appleton had expected happened. In the struggle that he was still putting up the pistol went off, being noiseless and smokeless. Appleton knew only by the fact that a man who had been trying to subdue him suddenly went backward with an ugly hole in his forehead. At the same time a man, who had been attacking Mackenzie, tumbled to the deck as the Scot managed to fire, and the next moment to have his arm well-nigh twisted off by one of the little men, who, despite their diminutive size, were very powerful.

Wrapped about by the clinging, cloying nets, the adventurers had little chance, and they knew, now that their weapons were gone, they were helpless; and their assailants made pretty short work of them by giving each of them a crack on the head with a flat-bladed weapon like a canoe paddle.

AS soon as the adventurers had been reduced to unconsciousness, their assailants set to work to complete the scheme which they had had in mind. The fear that they had displayed was all part of their plot to lure the strangers into their power, as also had been the concealing of arms, except the long barbed spears. They possessed other and more powerful weapons, as their prisoners were to find out before much longer; but they had argued that to appear to have only what were, after all, primitive weapons, would inspire confidence in the visitors, which was just what the inhabitants of the floating houses desired, because they had made up their minds that the ship that could not only fly and travel on the sea, but could also descend into the depths and rise again, was a prize worth obtaining. The desire to possess it unspoilt had been behind their failure to use their more powerful weapons.

The success of their scheme seemed to cause them much pleasure—and it was a very excited body of men who went over the aide of the ship and dropped on to the top of the Marsobus.

There were half a dozen of them, and, after peering curiously into the still open trap of the Marsobus, each man firmly gripping a peculiar-looking object, spherical shaped and having the appearance of a bomb, they climbed into the hole and descended into the main cabin of their prize.

From cabin to cabin they went, touching nothing but gazing curiously at everything. It was as though they were afraid to interfere with things that were strange to them. Certain it was that they were interested very much in the gun which, still protruding from the side, had caused the damage to their own vessel.

They were interested and surprised at all they saw, and held excited conversation about nearly everything.

But their greatest surprise was shown when they found the unconscious Ashby lying in his bunk, where he had been placed after the encounter with Mackenzie. All through the exciting events of the past hour or two Ashby had lain in his coma, and his companions had, when occasion allowed, examined him to make sure that he was still alive. Also, Appleton had several times tried to revive him, but without avail.

The strangers jabbered away when they saw Ashby. They touched the inert body, listened for heart beats, and shook their heads as if to say that the man was dead. Nevertheless, they were evidently not convinced, for while one of them went out of the Marsobus, the others cut the cords that Appleton had placed on Ashby for safety, and when the other man came back they administered something out of a bottle that he had brought, forcing the liquid between the teeth of the unconscious man.

They waited a little while, and then, as nothing happened, forced some more of the medicine into Ashby, holding his head in such a way and rubbing his throat so that the liquid made its way into the body.

But, do what they could, Ashby remained in his coma, and at last, after a short conversation, it was evidently decided that he was dead.

Once again a messenger left the Marsobus, to return after a short while accompanied by another man arrayed in the costume made out of fish skins, but which, instead of ceasing at the waist, continued up to the neck, and with a head-piece made of a sword-fish's head, with the sword as surmounting ornament. The men in the cabin salaamed before him, and then showed him the inert body of Ashby.

With an imperious gesture the new-comer gave an order, and the remaining bonds being slashed. Ashby was lifted up and carried to the top of the Marsobus. By this time twilight had fallen and the face of the waters was covered by a rising mist that hid the not far distant island and shrouded oven the close at hand vessel on which the fight between Appleton and his comrades had taken place. Without any ceremony or delay the bearers threw Ashby into the water. As though inured to death, they stayed not even to see whether their victim sank; the new-comer, evidently a person of high standing, issued further orders, and then clambered up the steps on to his own vessel, followed by all but two of his people—these latter being left on guard in the Marsobus.

Twilight, aided by the ever-increasing mist, deepened rapidly into night, and it was out of the darkness that, a very short time after Ashby had been hurled into the water, a figure climbed like a moving shadow up the side of the Marsobus. As though he were sure of his ground, the climber cared nothing for the rocking of the craft as he made his way to the top, where he paused and peered into the depths of the vessel.

Because of the darkness he could see nothing. Neither could he hear anything. He drew a wet hand across his forehead, as though trying recollect something. It was Ashby.

"Funny," he muttered. "How'd I come to tumble off? And why haven't they missed me?"

And Ashby, whom the sudden immersion in the water had revived, although he came back to life with the loss of memory of everything from the moment when he had made his outburst against being compelled to accompany his friends to the island, dropped, sidled over into the hole in the Marsobus and so made his way down to the dark cabin. He was puzzled by the silence, and told himself that something serious must have happened, because it was certainly unlike Appleton, for one, at any rate, to leave the Marsobus open.

"Perhaps the beggars have gone ashore and got nabbed," he said to himself, as he moved across to the switch and turned on the light, to find himself standing before two weird-looking creatures who, after staring at him for a moment in stupefied silence, burst into shouts of fear and made a rush at him.

Ashby met them. He struck the foremost one full on the point of the chin, and tumbled him back upon his companion. The couple fell in a heap on the floor of the cabin, and next instant Ashby was on them. He was possessed of the strength of madness again, and he pummelled the strangers soundly. One of them he knocked into unconsciousness, and the other, seizing by the throat, he almost throttled before he hurled him across the cabin and crashed him against the side.

"Think that's about put them out," Ashby grunted. "Where the deuce are Appleton and the others?"

That they were not in the Marsobus he quickly saw by going through the machine. He secured an automatic from the arms-chest and went back to the main cabin, to find that one of the men he had knocked out was gone. Ashby rushed up to the top of the Marsobus, and the upglare of light from inside showed him the figure of the man climbing the side of the ship alongside.

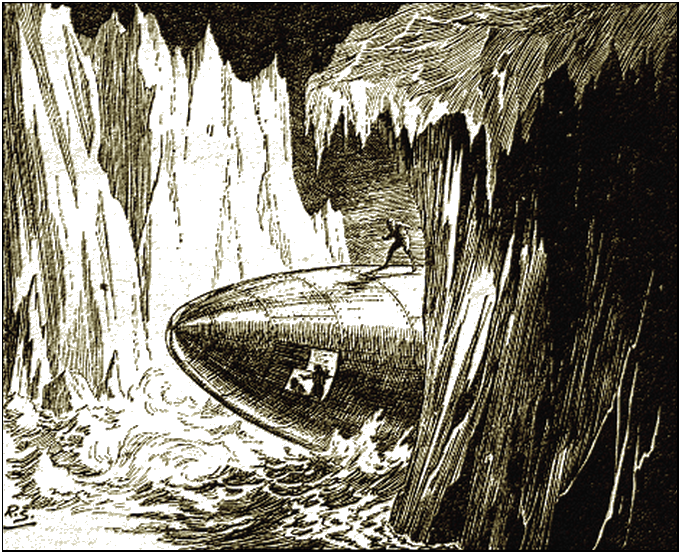

Ashby fired promptly, and the man lost his hold, tumbled backward, and dropped into the water.

But if Ashby had hoped that by this he was preventing the alarm being given, he was mistaken; and naturally so, because the light in the Marsobus had attracted attention from several ships, and the one nearest the Marsobus became crowded with men, who showed clearly in the light that seemed to run all round the ship, very much as though there were footlights at the sides of the deck.

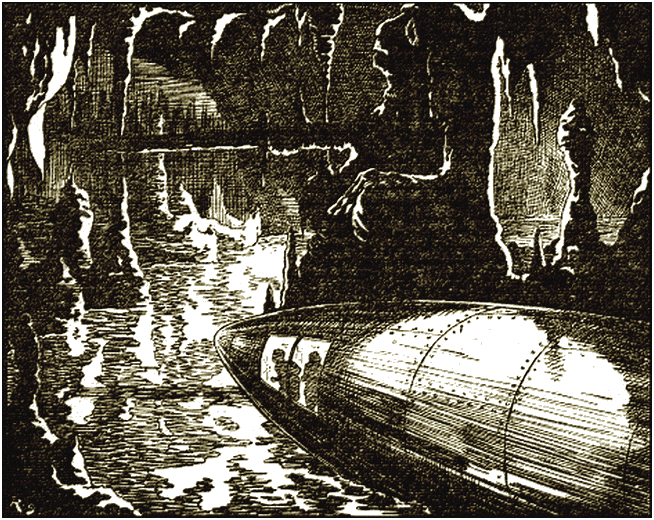

Ashby, whose mind seemed amazingly clear after all he had passed through, jumped back into the Marsobus, shut the trap door, set one of the engines working, closed all the ports, and manipulated the submersing apparatus. The Marsobus began to descend, her filtering light through the water being the only sign given of her whereabouts to the people on the ships.

Ashby decided not to go very deep, and brought the Marsobus to a standstill.

"I've got to find out somehow where the others are," he muttered, glancing across at the man whom he had thrown across the cabin, "The question is how?"

He went over to the man and examined him. Finding that he was not dead, he proceeded to bind the man's wrists, ready against the time when he should recover. He picked up the bomb-like object which was on the floor, where it had been when he first saw the two men after switching on the light.

"Don't like the look of that," Ashby said to himself. "Might be dangerous. Better shove it away."

He took it and laid it in one of the small lockers, and then returned to his prisoner. He tried various means of restoration, and after a considerable time had the satisfaction of seeing the man open his eyes.

"That's better," Ashby said, and then knew himself at an impasse, since the man could not understand him and he could not understand the man, who was staring at him with eyes that held no little fear. It was as though he were seeing a man who had returned from the dead, and Ashby was indeed to him such a man, since he had only a little while before helped to throw him while still unconscious into the water.

Ashby, however, knew nothing of this, and proceeded to make various signs to the man in the hope of being able to make him understand that he was asking where the other occupants of the Marsobus were.

For a long time Ashby continued in this work, but the prisoner maintained an impassive face.

At last Ashby reported to threats. He took the man to the window, through which could be seen the denizens of the deep—creatures that were fearsome enough to scare any man, even as they had scared Ashby himself not so long before; although, strangely enough, they seemed to hold now no horrors for him. Somehow he made the prisoner understand that unless he gave the information that was being asked of him he would be thrown into the water, as it was quite possible to do by means of the diver's outfit that enabled a man to issue from the Marsobus even while it was submerged.

But the man only smiled and shrugged his shoulders. Ashby could not understand it. He put it down to the man's pluck. That this was not so, however—though what else it was he could not for the life of him think, though he was to know later—was proved when he whipped out his pistol and thrust it into the face of the captive. The man instantly began to tremble again, and Ashby, who, of course, had not seen what had happened between Appleton and the people on the ships, at least was able to put two and two together and to guess that there had been trouble, in which pistols had been used to some effect.

"That's got you!" Ashby said; he succeeded, as he thought, in getting the man to agree to take him where the other occupants were.

Ashby, however, was under no delusion regarding the dangers that lay ahead of him, but had little doubt that very determined efforts would be made to take him prisoner as well, and he knew that he would have to work out a plan of campaign.

The first step was to get to the surface, which Ashby was not sorry to do. He switched off the light and set the Marsobus rising close enough to the surface to enable him to use the telescopic periscope. Sitting at the mirror, he examined the reflection and saw the mist-wrapped sea blackened with features that looked like shadows, but which he knew were ships, the indefiniteness broken here and there by splashes of light.

"The beggars are on the look out here," Ashby muttered. "But how the deuce I am to manage things I don't know!"

Not even the fact that he had got the prisoner to agree, as he supposed, to assist him would be much help after all, for the simple reason that it did not seem possible to get to know from him just where the captives were. Ashby pondered over this problem for a long time, and at last decided that it was necessary to interview his prisoner again. He went and fetched him from where he had left him, and, placing him at the mirror, showed him the vague shapes of the ships, his idea being to get him to say if the prisoners were on one of them. How he managed it Ashby never quite realized, but at last he did succeed in eliciting what he took to be agreement that the prisoners were on one of the ships. The question as to which ship was more difficult to answer. Ashby decided to take the risk and to go up to the surface, and, lying well away from the vessel, endeavour to get the man to indicate the one on which the captives were.

Shortening the periscope as he went up, Ashby raised the Marsobus until it was almost on the surface; and then, taking in the periscope altogether, made the machine break surface.

With lights out the Marsobus lay on the water, and Ashby, uncovering one of the windows, peered out, hoping to be able to see the vessels plainly enough for his purpose. As far as he could judge, the Marsobus had ascended to almost the same spot as she had been before, and yet, such was the mist, it was impossible to distinguish the ship near which they had been lying.

Only Ashby had an idea that his comrades were likely enough on that vessel, and at any rate it provided a steering point.

He at last determined to take the chance of turning on the searchlight and sweeping the surface to seek for the ship that had the great hole in its side. Dark as it had been when the man who had escaped him climbed up the near-by ship, Ashby had been able to see the hole, and, putting two and two together, had guessed that it was caused by a shot from the gun of the Marsobus.

The light streamed from the Marsobus and penetrated the mist, breaking upon the ship, which proved to be the one with the hole.

Feverishly Ashby forced his prisoner to look at it, and then shutting off the light made himself understood.

And the prisoner nodded—which Ashby took to mean that his comrades were not on the vessel.

But things were happening. The "enemy" came to life, as it were. From a score of vessels there sprang vivid lights, not in the form of searchlights, but glowing balls as of fire, which threw a brilliance over a very large urea. Followed by these, before Ashby quite realized it, from the crowded decks of the ships that were nearest, there came what to him seemed to be lighted "blankets" thrown with great force. As they swept through, the air, having all the appearance of zigzag lightning, they seemed to spread—and the next that Ashby knew, even as he touched the lever that would have sent the Marsobus back into the depths, was that one of the "blankets" had fallen on the machine. And when he tried to get the Marsobus to move, it was to find that she was held sufficiently to prevent her from making the progress that she ought to have done.

"Caught—like a netted fish!" Ashby rapped, forcing the lever over; but the propeller did not answer, and it came to him at once that it had been fouled. Moreover, the Marsobus was being slowly drawn along the surface, and Ashby's prisoner laughed aloud. Ashby could not see him because of the darkness, and it was perhaps as well for the prisoner, because Ashby was in the frame of mind to have done anything in the moment.

And Ashby determined to make a fight of it.

The Marsobus, going along the surface at the will of the unseen power that drew her, was still able to do something for herself; so, at least, Ashby was able to see her as a weapon. There was no need for him to turn on his searchlight in order to pick out an object at which to fire, which was his intention. The lights on the vessels were sufficient to guide him, and, with the enveloping net fogging his vision, he brought out the port gun and, sighting it, fired at the nearest object. That object was a light, which was instantly blotted out, and Ashby knew that he had found his mark.

And then, going to the ammunition cases, he found to his horror that there was but one shell left. At the same time he realized that even had he possessed plenty of ammunition he could not have hoped to do anything more than cause damage to the enemy, who in the end were almost certain to win, seeing that they had managed to catch the Marsobus. Ashby knew that the game was up. It seemed to him that there was nothing for it but to surrender and trust to luck.

Then the thought came to him that after all he ought not to throw in his hand altogether—there were his companions to be thought about. While he remained free there would always be the chance that he might somehow succeed in helping them, though how was a conundrum as dark as the deep blackness of the interior of the Marsobus or the now almost impenetrable gloom outside.

The thought of "outside" seemed to give rise to something in the man's brain. Switching on one of the lights, he moved across the main cabin to one of the lockers in the side, and took from it the diver's headpiece. His captive, who was grinning from behind the heavy beard that shrouded his flat face stared at the strange-looking object. And Ashby, realizing that for the purpose of the mad plan he had conceived, it was advisable that this man should not see what he did, turned off the light again—and there in the darkness he put on the helmet. Then, having seen that his automatic and a fair supply of ammunition were in a waterproof pouch, he moved quietly over to where the emergency under-water exit was. He opened the inner door of it, went inside, fastened it again, and then, touching the push that controlled it—was discarded into the water, the door closing tightly behind him.

It was indeed a wild scheme that he had formed, his object being to get to the inland, which was, after all, only about two hundred yards away not very much of a swim ordinarily, but one that he knew was fraught with danger because of the monstrous fish that seemed to swarm in the waters there. Had Ashby seen that race between his comrades and the sword-fish, not even he might have essayed the foolhardy project on which he had set out; but, as it was, the instant he was in the water he began to strike out towards what he knew was the coast.

"There's one thing," he said to himself as he swam with as little sound as possible, "that prisoner of mine will remain a prisoner, unless his people can smash open the old bus to get at him. And another thing is, with the shutters all closed, they'll think that one of us is inside and yet won't be able to prove it; and, goodness knows, their fellow won't be able to make himself heard through the double shell of the bus."

Ashby also realized that, with the enemy confident that he was in the machine, they would not be on the qui vive for him as they would have been had they known he had managed to get out. The thing that worried him chiefly at the moment was the fact that at any time the enemy might send up more of their brilliant and lasting fire-balls—and it was as a counterfoil to such a contingency that he had donned the diver's helmet, because with it he would be able, if necessary, to swim under water for a very long time, being a splendid swimmer and a stayer.

As luck would have it, however, there was no need for this, as no lights went up. The mist made it dark enough for him to be sure that he would not be seen from any of the ships, while at the same time it made his own work the harder since he had to be careful. He had taken his bearings by the dim points of lights that betokened ships in the mist, and beyond which lay, as he knew, the land for which he was making.

What he would find there, he had not the least idea, neither did he know what he would do afterwards. The present necessity was to get there. So he swam on and on, past the coming wraiths that were ships, and in passing them he swam beneath surface. Constantly there was with him the dread of attack by some monster, and, as every yard was covered, he could have shouted with joy because nothing of the kind had happened.

It was, however, a joy that was short-lived. He passed half a dozen ships, and, seeing the still lights that spoke of the island, had turned aside from his original course, intending to make land at a spot where there was at least no light, whatever else might be there, when suddenly out of the mist there appeared before him two glowing orbs that were not the lights of a ship. They were lights that lived—and moved towards him.

Ashby's heart well-nigh stood still as he saw the great orbs of light which he knew were the eyes; but a second later he was forging away from them, driven onward by the fear that had come over him. He heard a swish and a lashing as of a many-tailed thing, and although he had not been able to see the body he was certain that he was in the presence of an octopus. Gone now was the necessity to keep silent for fear of being heard; in fact there would have been an advantage in having them hear him, since in that darkness Ashby knew that he would be no match for the ogre of the seas if it should come to a fight. Yet he could not shout because of the helmet he was wearing, and his only chance seemed to be to put as great a distance as possible between himself and the octopus. He had whipped his hunting-knife from the sheath where he had placed it before going out of the Marsobus, and he swam with it gripped tightly, even although to do so made swimming difficult. He had turned again so that he was moving towards the lighted shore, willing to take the risk of being seen—and the shore was nearest.

NOW and again Ashby looked backwards and saw eyes gleaming phosphorescently in the gloom, and thanked providence that he was a good distance away and, as far as he was able to judge, gaining.

Then of a sudden the eyes disappeared; several times Ashby looked round fearfully lest he should see them again, and yet fearfully too, lest he should not. Because somehow he now felt the danger to be greater since he did not know where the brute was. Now he realized that at any moment he might feel the coiling grip of a tentacle about his legs, since the octopus, moving swiftly, silently beneath the water, might be able to gain upon him. Added fear gave added strength, however, and Ashby forced himself forward at a pace that amazed him. And as each yard was covered and yet he was unmolested, he began to think that he would win out after all.

And win out he did, to the extent of getting near to the shore, as he knew by the fact that his feet touched the bottom.

"Thank Heaven!" he breathed, standing up, and he looked out across the water. Behind him now lay the land, with lights that spoke of people and enemies. In front lay—what? The water and—Ashby jumped as, even while he was wondering if the octopus had gone, he felt something touch his foot—something that curled about it.

And then before he had recovered his balance the terror was in front of him. It's shining eyes were there again, and this time he fancied he could see the waving tentacles. At any rate, he felt them the next moment, for they were about him, noisome in their touch and grim in their meaning.

In front of him was the terror! It's shining eyes were

there again, and the tentacles waved menacingly in the air.

Ashby struck out at the dark spot between the eyes, and his knife sank deep, so deep that it was with difficulty that he managed to get it out again. And the tentacles were closing more tightly about him. Again he struck, and well, just at the moment that the darkness was broken by a glare above him, and he knew that once more the enemies from whom he had tried to escape were acting again; probably they were going to complete their capture of the Marsobus. Ashby did not know. All that he knew was that the light was a thing of which he had been afraid not so long ago; now it proved to be a friend, for it gave him the chance to see his present foe. Time and time again, while the light held, he slashed at the octopus, until the brute was nothing but a ribboned remnant of its old self, while Ashby, exhausted by his tremendous efforts, slumped into the water. The dousing revived him somewhat, and he compelled himself to scramble up and stagger onwards towards the shore, reaching it just as the light-balls died away.

Strangely enough, during the battle with the octopus Ashby had not thought of his other foes; had not, indeed, had time to spare for a glance seawards. If he had he would have found that he had been standing in the water in what was really a cove, sheltered from the outside, which could not be seen into from where the ships lay off the harbour. Now, as he staggered on to the dry land, be began to realize why it was he had not been molested, or an attempt made to capture him. He had not been seen.

Fear of the rising of other fire-balls, with the chance of not being seen next time considerably uncertain, made Ashby decide that it became him, for the time being at any rate, to conceal himself and not try to move far until he had had time to get an idea of the lie of the land, which he could only do during the day-time. The last of the fire-balls, as they died away, had shown him something that he believed would provide him with a temporary hiding-place at least; a cleft in the wall of rock beyond the stony beach on which he stood. Brief though his glimpse of it had been, he had yet noted its position, and be strode in the direction of it. Well aware that the cleft did not start from the ground but was placed some distance away, he had to make sure that he was beneath it, and also to find a way by which to reach it.

Because of the darkness, he knew that he would have to take the risk of using his electric torch, which he had carried with him in his waterproof pouch. He switched it on behind the cover of his soaking jacket, cupped it in his hands so that the light from it was dimmed as it streamed out, and, throwing its beams against the face of the rock, he searched for the opening that meant so much to him. He found it after a while, and saw that, although it was some ten feet above, it was accessible owing to the broken character of the rock beneath. He turned off the light, conscious that to use it any longer while climbing might be to court discovery, and then began to make his way up relying solely upon the sense of touch. It was fairly easy to him, even although he was very nearly "all in." It was merely the undaunted courage and fine determined will of the man that kept him going until he finally reached the cleft, which he found was wide enough to allow him to got inside it.

It was then that endurance failed; and Ashby, dropping to the uneven floor of what he imagined to be merely a small cave, lapsed into an unconsciousness that had at least something to its credit, inasmuch as it was different to the coma in which he had laid during the many hours immediately following his outburst of mad rage against Appleton. It was sleep—sleep born of sheer physical exhaustion, and it was sleep that, lasting for many hours into the following day, served the purpose of refreshing him, at the same time that, by one of those strange happenings with regard to the human brain, brought back the memory of what he considered the injustice of Appleton in prolonging the journey back to Earth; and, moreover, made Ashby's mind a blank regarding what had happened from the moment when he had dropped into his first coma until that in which he found himself standing upright in the cave and looking out across the cove with just the merest glimpse of the water beyond.

"Marooned me!" he said savagely; "that's what they've done! The brutes! Must have given them something to think about!" he was looking at his bloodstained clothes, imagining them to be the token of the fight which he remembered starting. "Well, anyhow, one of 'em got a packet to be going on with. But what the deuce did they shove this helmet on to me for?" He unfastened the diving helmet as he muttered to himself. He was wondering, too, how it was that his clothes were soaked through—because the moist night air had not allowed them to dry while he lay asleep.

Ashby's mind was now as alert as it had ever been—apart from the hiatus in memory; and he was filled with anger at what he honestly believed to be his desertion by his comrades. The thought uppermost in his mind, however, was what he was to do about his own situation. He remembered that while he was in the Marsobus he had seen people on the land, and the problems that confronted Ashby were first, food; and secondly, how to evade the inhabitants, or, at best, how to placate them if he were seen and captured.

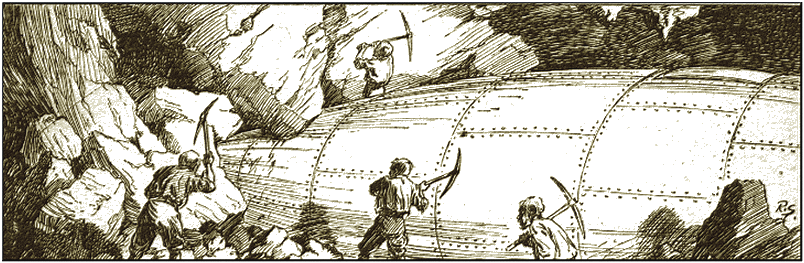

The insistence of the body for food forced him to begin his task at once; and very carefully he made his way down to the water's edge to reconnoitre the position off the land. Arrived there, he peered around the bend, and saw a number of the large vessels, some moving out to sea, others still at anchor, and lying alongside the rugged coast, not four hundred yards away, the Marsobus.

"Gee—the old bus has been taken!" Ashby breathed; for there was no mistaking the position. A dozen of the strange-looking people were on top of the Marsobus, using queer kinds of tools in their very evidently difficult task of trying to make an opening in the machine.

Ashby's first impulse was to use the automatic that he held in his hand. Actually he raised it to fire, but then lowered it again as he realized the futility of attacking in such circumstances; and also as his consuming rage against Appleton made him mutter:

"Why should I help them?"

He did not know, of course, that his comrades were not in the Marsobus. His natural conclusion was that they had been unfortunate in a fight with the strangers, and that the Marsobus had either gone wrong, or the enemy had, by some clever means, managed to capture it.

For some little time Ashby remained hidden behind the rocks, watching operations on the Marsobus, smiling to himself as he saw the futile efforts of the strangers; and while he was amused by this, he was wondering what Appleton and the rest must be thinking about.

"Got the wind up, I'll bet!" he muttered. It did not occur to him that they must be in very severe straits not to be making some effort for themselves; and even if it had, in his existing frame of mind, Ashby would not have raised a finger to help them. He felt that his fate was taking retribution for the evil which had been done to him; and he was content.

The most astonishing thing about the whole matter was that Ashby did not yet realize that what was happening meant his own doom, just as much as it did that of his comrades. The truth was that his brain was deranged, though he was self-careful enough to take steps towards what he considered his own safety—at the same time he forgot that safety might really be in the direction of assisting his companions. Perhaps it was his obsession. Perhaps, on the other hand, it was a scarcely realized idea that whatever the enemy might do, he couldn't conquer the metal of which the Marsobus was made—but the fact remained that Ashby—instead of doing anything to help the comrades whom he thought were in trouble—after a while withdrew from his hiding-place and made his way back to the cleft in the rock from which he had issued such a little time before.

Hungry and wet, but realizing that as far as the possibility of food was concerned matters were hopeless, Ashby's greatest concern was to remain concealed until the coming of night, when he would be able to go out and search the shore in the hope of finding at least some kind of shell-fish.

While in the cave, however, forced inactivity naturally drove his thoughts to the question of final safety, and even in his half-insane state of mind the realization came that the future looked hopeless. Believing, in the first place, that his comrades had deserted him, he could not look to them for succour; while even if they had not cast him away, under the circumstances they would be unable to do anything, inasmuch as they were evidently imprisoned in the captured Marsobus. Also it became obvious to Ashby that his salvation depended upon himself—and the Marsobus. That meant that he would have to do something to recapture the machine, and that in its turn meant that he would have to rescue Appleton and the others. It was a long process of reasoning, but it must be remembered that Ashby was still obsessed by insane rage, and what previously would have been a very obvious course for him to take, he now regarded as the one to be avoided if any other way could be found.

But once he had reached the point of decision, he became fired with impatience to be doing. He paced up and down the cave into which the gradually dying light filtered, but did not reach the extremes of it. Unconsciously the distraught man lengthened the stretch of his pacing, and it was with something of a shock that after a while he discovered that there seemed to be no end to the cave. Up to then it had not occurred to him to use his torch, his mind had been too preoccupied with schemes and hopes for him to worry about the character of the place in which he was hiding. Now, however, he pulled out the torch and switched it on. The streaming light from it showed him what, in a calmer frame of mind, he might have discovered without a light. The floor of the cave had a decided inclination. Moreover, the cave was very narrow, almost like a tunnel, in fact; carved out of solid rock. The floor was uneven, and the roof, about the height of two men, was of stalactite formation.

For a few moments Ashby stood still and flashed his light here and there, wondering what lay beyond, and whether he should risk further exploration. Finally he decided that he would go at least a short distance, and, using his torch only intermittently to show him the character of the floor in case there might be crevasses, he proceeded into the darkness. What astonished him as he went was the length of the tunnel. He had been counting the paces, and had reached three hundred without reaching the end, and the question came as to whether it was worth while pursuing his journey any longer. At a point the tunnel, instead of easing up, began to go down very steeply.

"Just a little farther," he muttered, and went on much farther than he had really intended; and then curiosity had him in its grip, and he knew that he must remain to learn what there was to be learnt.

What had happened was that of a sudden, he saw afar off, not the glow of a moving light, but of a steady brightness, which suggested either that he was nearing an exit into the open air, or that there was some artificial light down there in the depths. As he thought about this matter, Ashby decided that the latter must be the case—since the twilight was not strong enough to give so much brilliance.

Ashby went on, impelled by curiosity. Now and again he used his own light, but less frequently in case the light beyond indicated the presence of people. Carefully and quietly he picked his way, feeling by the rock-wall as he walked; and the light grew larger as he went, until at last he knew that there was need for more caution. Coolly he drew his automatic from its waterproof case and then moved forward, almost creeping, so quietly and so slowly did he go. He could see the end of the tunnel: it was as though it ended as a corridor ends by leading into a hall.

The glow lighted up the tunnel now, and Ashby was afraid lest he might be seen; but having come so far he determined to carry on. He hugged the wall and came to the arch, peered out, and gasped with astonishment.

The tunnel ended on the very edge of a pit, at the bottom of which was a city seeming built of marble. It was a wonderful sight. From the roof, which was about ten feet above the tunnel in which Ashby stood, hung what looked like a series of beautiful curtains chiselled out in marble. The walls of the pit itself, which was hundreds of yards in diameter, were of rock, with what Ashby took to be houses cut into them; while great pillars of white substance reared up from the floor to the roof, and this white substance threw back a scintillation of light as the brilliance of a mysterious light cast itself upon them.

There were houses built in rows; and the streets, all of which led to a central square, were filled with people moving towards that place. In the centre of the square was a marble-like plinth, which Ashby judged to be some twenty feet in height. It was flat-topped, and there were steps leading up to it. The people were all dressed like those whom Ashby had seen above.

Ashby had flung himself down and was watching the scene. He had forgotten everything in the fascination of what he saw, and the murmur of thousands of voices coming up from below—the pit was at least a hundred feet deep—droned in his ears.

"Dropped in on a ceremony!" The thought ran through his mind.

He was held by the wonder of it, and his curiosity made him careless as to whether he were seen or not. As he watched, the crowds of people gathered in the great square and stood tightly packed around the plinth, looking up at it as if waiting for something to happen.

And when it did happen there was a roar, in which Ashby himself very nearly joined from sheer astonishment.

The top of the plinth opened as if there were a sliding panel to it, and from inside it there issued a man taller than the rest of his fellows, but dressed the same as they with the exception that he wore a head-dress that attracted attention immediately, because of its remarkable character. Ashby realized that it was made out of the head of a sword-fish, and the sword was still attached to it. The man stepped on to the plinth, and there came after him three other figures, which to Ashby's amazement, turned out to be Appleton, Mackenzie and Teddy Craig. Behind them were several of the strange people; and as soon as all were on the plinth, the panel slid back into place. The man with the head piece turned to the assembled crowd and seemed to beckon for silence, which he got instantly, and then he went on talking for a long time, every now and again having to stop because of the uproar as of cheering. He kept pointing to the three captives, whose arms were securely tied behind their backs, while their legs were free.

"Probably holding an inquest on 'em," Ashby muttered.

He watched and listened to words that he could not understand, but the grim meaning of which he grasped after a while. Suddenly the captives were seized by their guards and forced to lie on the grating on top of the centre of the plinth. Ashby had wondered what that grating could be for, but now he was to know. The prisoners were bound to it, not without a struggle. They were secured and could move neither leg nor arm. The man who had been speaking to the crowd said something to the guards, who disappeared through the sliding panel. The leader spoke to the prisoners, making vigorous signs as he did so, and the fact that Appleton shook his head told Ashby that he understood what was required of him and was refusing.

The man stamped upon the plinth, and there came an answering shout from below, followed a few minutes later by smoke issuing, from between the grating on which the prisoners were lying.

Even then Ashby did not quite realize what was taking place. It was only when the smoke gave place to a dull red glow that the full truth broke upon him.

"Being grilled, by George!" he almost cried. And to his credit, let it be said, for the time being he forgot all about his own feud with them and determined that the moment had come for him to take action.

He raised the soundless automatic and fired straight at the man who was the leader. He spun round, throwing up his arms as he did so, and then tumbled off the plinth. There was a rush on the part of the people standing nearest, and a great uproar ensued.

"Looks as though I've done it on him!" Ashby muttered grimly, as he saw the consternation amongst those who had raised the man and were examining him curiously. They dropped him back to the ground, and one of them rushed up on to the plinth and ran down through the panel. A second or two later the guards rushed on to the top, and Ashby saw that their feet were differently shod from what they had been before. They walked on to the grating and cut the bonds that tied the prisoners to it, lifted them to their feet and drove them below.

Ashby's self-satisfaction at the success of his shot was short-lived. He had known that, and relied, upon the fact of the silence and suddenness of the downfall of the leader would most likely cause confusion and perhaps interrupt the course of events. What he did not know, of course, was that the people below, or at least some of them, had experienced the effect of the silent weapons during the ensnaring of the captives on the deck of the ship while Ashby himself was lying in his coma in the Marsobus. He had hoped that they might be superstitious enough to lay the striking down of their leader at the door of Fate, as a retribution for what they were doing to their captives; but actually what happened was that they understood that in some way the fourth man who, as the fugitive from the Marsobus had told them, had been thrown overboard and then returned to the machine, was actually in the underground city.

Despite his ignorance of all this, Ashby interpreted aright the next move on the part of the people below. The great lights went out suddenly and the glow beneath the grating on the plinth was the only patch of light.

"They've tumbled to it that someone's about!" Ashby muttered; "and they're going to search. It's me for the open air!"

ASHBY realized that the people would know all about the tunnel in which he stood, and at the same time he realized that there were probably several other tunnels leading to the city, and that the enemy would guess that he had come by one of them.

He went rushing up the incline, reached the top, and then ran down to the tunnel mouth.

As he ran he had formed a scheme which he knew would, if successful, not only mean that he would escape for the time being at any rate, but would also serve to mystify the enemy.

At the cave-month he had left his diving helmet which he now put on. He placed his automatic into its case, and scrambling down the rock face, ran to the water's edge and waded out until he was able to walk beneath the surface.

And he began to walk parallel with the shore in the direction of the Marsobus.

Walking, as he was, beneath the surface of the water, Ashby had nothing to guide him except his sense of direction, and yet, so confident was he, that he felt he was going right. He did not dare to use the torch that he carried: the light of it would have been seen from above and the success of his scheme, in all its aspects, depended on his being able to carry it out secretly. It was to be in the nature of a surprise for the enemy.

So he went on slowly, passing here and there the shadows that signified ships, and always moving in towards the shore when he felt the sea-bottom declining outwards. The absence of his diver's boots meant that he must keep always only just below surface; and therein, of course lay a danger, though, as it was nighttime, that danger of being seen was considerably reduced.

For hundreds of yards he walked, now and again going nearer to the shore so that in the shallower water he could put his helmeted head out and see how near he was to the Marsobus. It was at the sixth time of doing this that he received the surprise that suggested he must alter his plans; until he finally came to the conclusion that, although it changed in some respects, it might still be carried out in the main.

What he saw was the Marsobus lying bathed in a blaze of light as a searchlight flashed its beam upon it, and at the shore, near which it was moored, were Appleton and Mackenzie and Craig, together with a number of people dressed in the shiny scaly clothes.

"What's a-doing?" was the thought that ran through Ashby's mind as, within two hundred yards of the Marsobus and well outside the stream of the searchlight, he stood, half-head only above the surface, and watched.

Naturally, he made no further move towards the Marsobus; the plan now was to learn what was afoot. He was soon to learn.

He saw Appleton lifted, struggling, by several of the strangely attired men, and laid, face up, on top of the Marsobus, while other men went into the water carrying ropes. Yet others straddled across the Marsobus, and within a few minutes Appleton was bound to the machine, with ropes round his ankles and his arms outstretched above his head. By the time the same thing had been done to Craig and Mackenzie—the former at the bow, the latter at the stern, with Appleton in between them—Ashby had grasped the idea. Ashby saw one of the men speaking and gesticulating to Appleton, as though he were being given a last chance; and Ashby suddenly roused to the reality of the situation and the necessity for him to take his own action.

One of the men was gesticulating and speaking

to Appleton as though givimg him a last chance.

Previously his plan had been to get into the Marsobus via the underwater "diving door," and to mystify the enemy by working the machine away from the shore, after having cut the cubic with which it was moored. That would have meant that while the enemy were searching for the man who had killed the leader in the underground city, they would be made aware that after all the strange machine was being operated. That, however, would have meant that Appleton and the others would have to be left; which, after all, Ashby did not mind, except that his own safety in the end depended upon that of his comrades.

Now, however, he realized that not only did he stand a chance of getting into the Marsobus, but also of effecting the rescue of his companions—if everything worked as he hurriedly thought it out.

He stepped back into deeper water, and walked towards the Marsobus, troubled mentally as to whether he would reach it before the enemy cast off the Marsobus—because Ashby had clearly understood that the intention was to send the craft off on the tide—with its strangely prisoned crew aboard.

Ashby hurried as well as a man in such circumstances could hope to hurry, and although once or twice he had to go to the surface, he actually did reach the Marsobus while it was still moored. When he came within the down-glare of the searchlights, he had to be careful lest his form be seen beneath the surface. It was the shadow of the Marsobus above that told him he had reached his objective.

He knew that the most critical moments had come. He must be careful about getting into the Marsobus. He walked beneath it, sheltered by its great bulk, until he reached the place where the diver's door was situated. Unable to see, and afraid to use his torch, he had to rely upon his sense of touch and his knowledge of the Marsobus; neither failed him, and at last he found the spot at which the door could be opened from outside. He performed the necessary work—and the outer shell of the Marsobus slid open. The next step was to get into the cavity; and this he did by grasping the rails that were inside and pulling himself up by a great effort. He felt the Marsobus rock and wondered whether the people above would be suspicious. He need not have worried, for at that moment they were cutting asunder the hawser by which it was moored, and as Ashby found himself inside the cavity and slid the door to, thus shutting himself in, the Marsobus was freed. He did not know that. All he knew was that he was inside, and a groping hand touched the mechanism that slid open the inner door and he was once more in the Marsobus, his immediate task accomplished, but others awaiting him.

He stood up, the water draining from him in a pool. He removed the helmet and stretched himself.

"So much to the good!" he said aloud, and there came an answering voice that made him start; he had forgotten the prisoner he had left behind.

"Gosh, I wonder what the deuce is that?" he said. And even then be failed to recall the incident immediately preceding his narrow escape from death in the clutch of the octopus. His mind was hazy and uncertain still.

For the moment he had nothing to do. He decided that for a little while it would be unwise to get the engines working. He must wait until he felt that the Marsobus had got sufficiently far away from the shore for anything that he did not to be noticed.

Caught by the tide, the machine was drifting off into the darkness and the mist, and Ashby, himself soaked through and chattering with the cold, wondered what Appleton and the others could be feeling like as they lay looking up into space, helpless to save themselves, and not knowing that there was help of any kind near at hand.

"They're going to be mighty surprised when they see me!" he chuckled, and there was only a grim humour in him. "They'll think I've come to get my own back. Wouldn't be a bad idea to show myself and then let 'em stay where they are for a little while longer! By George, I think I'll do that!"

Very cautiously he slid aside one of the window covers, knowing that the absence of light in the Marsobus would make it possible for him to see without being seen; and he found that although there was still the glare of light that told of the searchlight, it was not fixed upon the Marsobus, which evidently had made good progress on the bosom of the water.

"A little longer," Ashby muttered; but he did not shut the window this time: remaining by it and peering out across the waste to the rapidly dimming lights of the shore and the ships, until at last he judged that it was safe for him to act. Although he closed the windows he slid open the trap-door in the top of the Marsobus, and then switched on one of the lights; then ran up the steps that led out.

"What the deuce is that?" he heard a voice say—the voice of Appleton issuing from between teeth that chattered through the cold. The light was thrown up like a spurt, and it was this sudden glare that had made Appleton exclaim.

"Must be Ashby—thank goodness!" said Mackenzie's voice. "Though how he got free I don't know. Hallo—Ashby!"

"'Lo, Mac," said Ashby, stopping on to the top of the rocking Marsobus.

"Pretty fine mess you lot are in."

"Thought we were," Appleton said; "but now you're here it's all right and—"

"Yes—all> right!" Ashby almost snarled. "You go and maroon me, glad to be rid of me, and now—now—"

"I say, Ashby, old chap—what are you talking about?" Appleton broke in, utterly astonished. "You've gone mad—to think that we deserted you and—Look here, cut us free and then we can talk about things."

"Why should I? D'you think I want> to talk about things?" Ashby said tauntingly. "You can stay there and freeze!"

He stepped back into the machine and actually slid the door to above him. And his amazed comrades were left to make the best of a business that they could not understand.

"Must have gone fey, Chief," Mackenzie said. "It's a mystery."

"Mac," said Appleton, "I'm beginning to see light, I think. Somehow Ashby managed to get free—likely enough he was captured and escaped. Also, I'll bet it was he who knocked out that fellow in the underground city—though how it all happened I can't guess. Then he must have come back here—did you see—no, you couldn't where you are. But I did. He's dripping wet at this very moment, and I shouldn't be surprised if we find that he got into the bus through the diving door while she lay moored."

"Doesn't seem as though it's going to do much good for us however he got in," Craig put in. "What's he mean about being deserted?"

"Can't imagine—Unless he came round and found himself bound, and was cut free by the enemy. Poor old Ashby. I'm afraid his mind's gone a bit rocky. I . . . hallo—he's got the engines going!"

It was a fact that the Marsobus, instead of drifting as she had been doing, was now pushing a purposeful way through the water; and as she was moving at a very rapid speed, the three men bound to her, in as grim a situation as ever men have found themselves placed. Were well-nigh frozen by the rush of wind.

Although they did not know it, Ashby was sitting in the steering cabin, with the window open and peering across the waters, on the qui vive against colliding with anything; and he was enjoying himself. He had a further little scheme he was going to play, and he proceeded to do so. He ballasted the Marsobus slowly, and she began to submerge. The water lapped up and about the three men outside, and Appleton, who had been the first to sense the new motion, but had been afraid to mention it, now yelled out with fear.

"Mad—mad as a hatter!" he almost sobbed. "He's going to drown us!"

But the Marsobus rose again, and presently the engines stopped.

"Only—trying—to scare—us—Chief!" Craig managed to choke out.

"He did it well!" Appleton said with a shiver. "I wonder—Here he comes!" as once more the door opened and the light streamed out.

"You mad fool!" Appleton shouted as Ashby's figure appeared.

"Not so mad—not so mad!" Ashby chuckled. "I'm out for a bargain with you. You wouldn't agree to go straight home before; but now you've got to agree, or else you'll never go home at all. I'll just close the trap and submerge! It's up to you! I'll take the risk of being able to get the old bus back!"

The ultimatum thus presented to them left the three bound men speechless for a while; they could only stare at Ashby as he stood, half in and half out of the Marsobus, his rugged figure thrown into bold relief by the light streaming up from within.

It was Appleton who found his tongue first—and that only because Ashby rapped out:

"What about it?"

"Look here, old chap," the Professor said, "you've got the master-hand in this game; and, after all it's not altogether fair for you to play it when the rest of us are—I thought you weren't well—you've been such a good fellow all through, and—"

"No butter!" exclaimed Ashby. "Lordy, how I'd like a pat of butter!"

The unexpectedness of that was sufficient to make Appleton, for one, laugh, even in those circumstances—it was so ridiculous, and Ashby himself joined in. What the effort would have been—whether that momentary and involuntary sense of humour would have had any favourable result—must be left amongst the unknown things; for, just then, there came an almost blinding glare of light upon the Marsobus—and everyone knew that it was a searchlight from an enemy vessel.

"Quick, Ashby!" cried Appleton, first to grasp the meaning of it. "We'll all be snaffled. Free us and get us in—now!"

With one of those strange, mental freaks that were characteristic of him in his present state, Ashby, instead of seeking his own safety—which he could have found by going in, abutting the door, and submerging, quite heedless of the fate of his comrades—whipped out his knife, laid hold of Appleton, and slashed the bonds that held him.