RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

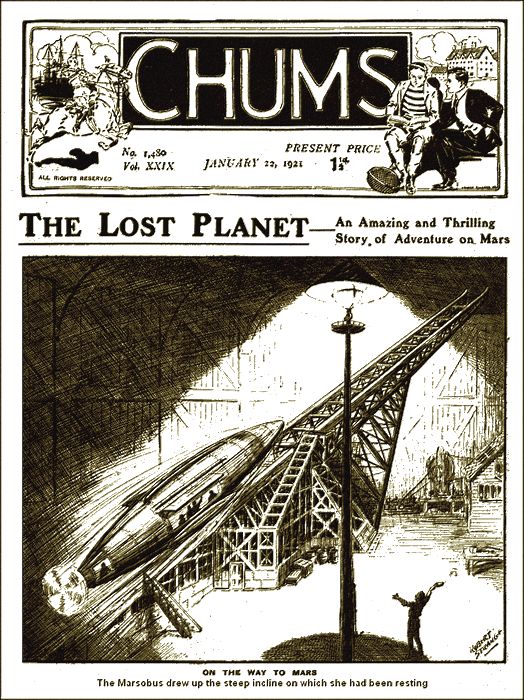

Chums, 22 Jan 1921, with first part of "The Lost PLanet"

TEDDY CRAIG, standing atop the hill that looked down upon Protton, the sleepy little old country town that was known for nothing but the fact that it held the great public school St. Christopher's, drew a hand across his eyes as he stared, blinkingly, at the towered school, touched by the early morning sun.

"All right," he gulped jerking up straight, as though defending himself against some unseen blow, "all right! They've turned me out—chucked the mud of their scorn at me, and wouldn't believe me when I swore I wasn't guilty! Just because I've been a wild 'un, though everyone knew I was harmless. All right!" he repeated. "Some day I'll show St. Kit's that I'm as good a man as the rest of 'em, and straight too!"

Craig turned aside, dropped below the summit, the weariness, that was more of soul than of body, which had marked him as he climbed the hill all gone now. It seemed that the very fact of having reached the hill-top had changed him. Half an hour before he had slipped out of St. Kit's via the window of a dormitory, having resolved not to wait to be carried off to the station—expelled for a crime that, wild as he was, reckless and dare-devilish, he had not committed. The Head, Dr. Mather, had had a valuable collection of silver relics stolen—and one of them had been found, a week after the affair, in Craig's study, slipped, quite evidently of set purpose, into a supposedly secure place. Craig had denied all knowledge of it—but the evidence was all against him. Dr. Mather had sternly denounced him before the whole school, and, saving that for the honour of the school he would call off the police, had formally pronounced expulsion—telling Craig that he left it to him to announce the verdict to his guardian. That had been last evening—and Craig seemed to have lived many years since that time. Throbbing through his brain were two thoughts: first, that he was branded a thief; and the second, that he would rather beg bread in the streets than go down to Devonshire and face his Uncle Joseph, his father's own brother, who, on the death of Craig senior, had been left the custody of Teddy, pending the time when he should come of age and inherit his father's fortune, which was not inconsiderable.

Now, as he went downhill, Teddy clenched his fists again, and muttered fiercely:

"I can't do it—I won't—it would break uncle's heart. He's the soul of honour himself. Was brought up at St. Kit's, and would believe, would feel compelled to believe, that the verdict is true. All right! Five pounds and my eighteen years are enough for me till I've made good on my own. Then I'll come back. It's London for me—and then, let the gods decide!"

Teddy felt bucked at his own determination; somehow, his foot taps sounded louder, his tread felt firmer. He might be out—chucked out—but he wasn't down. Not by a long chalk. Many a man had started in on life without five pounds: few had started with bigger hopes and stronger determination than he possessed just then, and he boarded the London train in what were really astonishing spirits for a youngster who had a cloud hanging over him.

He was alone in the carriage, and hunching himself up in the corner, settled down to read a previous day's paper that he found on the seat. It was a long journey to London—so long that he had consumed all the news and specials that the paper contained long before the heart of the land was reached. He did not want to sleep, he did not want to think—so he started in to read the advertisements. After a while he wandered down the "Personal" column, grinning as he read some of the effusions of the foolish—or the cunning: it was hard to know which was which. One few-lined personal did not, however, make him grin, even although it made him read it twice, thrice, and at last brought, a whistle to his lips.

"By Jove!" he exclaimed, "I'm on this, you bet! Why not?"

Why, indeed, anyone reading it over his shoulder might have asked, for the advertisement was couched in terms not altogether calculated to infuse a boy—even eighteen at that, and just expelled from school—with desire.

"DANGER! Professor Appleton, London University, requires four men not afraid to take risks in the interest of science and civilization. No scientific training needed—only brute courage. No remuneration, probably no reward except death; unless it be the fame that the world gives to those who are not afraid to die for a Great Ideal. Apply in person to Professor Appleton, 26d Harley Street, W.C.1."

A startling enough advertisement, that! Who Professor Appleton was Teddy Craig had not the least idea, and did not care. All that he cared was that there was a hint of adventure, a suggestion of something unknown, in the advertisement, and that something within him had risen to it, as a heart leaps to the call of his mate.

The feeling grew more intense as the journey lengthened, and Teddy was at such a fever pitch by the time he arrived at King's Cross, that, although he knew Harley Street was only a short distance away, he hailed a taxi caring nothing for the fact that he ought to conserve every shilling of his five pounds.

He rang the bell at 26d, the door was opened by a wizened faced man whose eyes gleamed like diamonds out of his parchment mask that went by name of a face.

"Professor Appleton, please," Teddy said crisply.

"He ain't in," was the man's reply.

"When will he be in, then?" Teddy asked "It's most important and—"

"That's what they all said," the man told him with a throaty chuckle. "Important as—as death." He bent forward confidentially. "See here, young fellow—"

What it was that the old man would have said Teddy was not to know, for at that moment a taxi stopped at the kerb, a man stepped out, walked up the steps, and the servitor muttered:

"The governor!"

Teddy turned, swiftly, expectantly, and instead of the venerable, learned looking old man that he had anticipated, saw a youngish man, not more than thirty-five, upstanding and virile, immaculately dressed—as little like the youngster's conception of what a professor should be as it was possible to imagine.

Teddy stepped aside, and the man, with scarcely a look at him, passed through the doorway.

"This young gen'man wants to see you, sir," the servitor said.

"Show him into the library," was the reply, without even a look back at Teddy, who, for some unaccountable reason, was both amused and annoyed at the nonchalance of the Professor, who strode down the hall and disappeared behind the door at the far end.

"Come in, young sir," the servant said, and Teddy stepped inside, was ushered into a comfortable room, and told to take a seat.

"'Member what I told you," said the man, with another chuckle, and went out.

"Well, I'm blowed!" said Teddy to himself. "He's a rum sort. Here I thought I was coming to a tremendous adventure, and dropped into a comic opera. Why the Professor has that old fellow for a servant or the old man has the Professor for a boss goodness knows. They don't belong, anyway! How long am I going to be kept here, I wonder?"

He was looking around the room as he ruminated, and, boy-like, could not resist the temptation to get up and walk over to one of the long rows of books. There seemed to be books on every conceivable subject, but the fact that impressed Teddy most was that science predominated, and of science astronomy—and one case was filled with nothing but books dealing with Mars. There seemed to be books on that subject in every foreign language—and in a flash there came to Teddy the remembrance of Professor Appleton's name, which when he first read it in the train, had conveyed nothing to him.

"By Jove," he said in an audible whisper. "He must be the Johnny who, so the papers said, talked like a Yankee stunt-merchant about making the trip to Mars! I wonder—"

"What?" came the quiet word from behind him, and swinging round, Teddy saw the Professor standing in the room, with a slight smile wreathing about his lips. "What is it you wonder Mr.—Dr—"

"Craig's my name, sir, Teddy Craig," the youngster said immediately. "Your man said you were Professor Appleton—therefore you're the man who put that ad in the paper yesterday. That's why I've come to see you, and—"

"You wonder whether it by any chance has anything to do with Mars, eh?" was the question. "Sorry I overheard you thinking, but I wasn't really eavesdropping, you know."

"It's your own house, sir," Teddy said, with a slight laugh, somehow feeling altogether at home in the presence of this young Professor. "And—well, you're right, that is just what I was wondering. It is for you to inform me if I am right. I should like to have details of the matter on which you advertised."

"Sit down, man, sit down. That's right." Appleton seated himself as Teddy took a chair. "You don't smoke, and you don't drink—I can see that. Which is all to the good. Got any parents to leave—any sisters or brothers and—Dr—anybody who'd worry very greatly about you? Professor Appleton was plunging into a series of questions without any explanation before Teddy had scarcely crossed his legs.

"My mother and father are dead," Teddy said simply. "I've got no brothers or sisters—I've an uncle who's my guardian who—"

"Is by way of being unsympathetic to the spirit of youth?" Appleton suggested, but Teddy shook his head.

"Far from that, sir," he said. "Uncle Joseph is a good sport—he likes me. Sometimes I think that it's because he's been so jolly decent that I've been so—well, wild, you know. Better hear my yarn first, sir, before we go any farther," and he went on to tell of the sequence of events that had ended in his coming to London. "That's the story, sir, and I leave it for you to believe or not, as you think fit. At any rate, I know I'm speaking the truth, and some day I'll show the fellows at—at the school!"

"I believe you, Craig," murmured the Professor. "Your eyes wouldn't let you tell a lie. I was just wondering whether—well—let's get ahead with things. You've had your say. I want mine. But first I want a solemn oath from you that whether we come to a clinch or not you'll say not a word to a soul."

"My word—my word of honour that what happens between us goes no farther, sir," Teddy said seriously, and almost impulsively, as a schoolboy will do, he thrust out a hand, which Appleton grasped.

"That's that," the Professor said. "Now listen. You've heard of me before—I know that from what you were saying when I came into the room. And you're right when you conjectured that I was advertising with a view to Mars. Those foolish fellows who write the stuff that gets into the papers not long ago had some wonderful things to say about what I thought getting into touch with Mars. My improved wireless which they said would send messages to Mars in no time; my statement—as they called it—that I was going to fly to Mars, all rubbish that, by the way, though I did once go into the question of the possibility of reaching the planet by airship. Proved that it was impossible, though, which was a pity, since it would have been very comfortable travelling."

Appleton was speaking almost casually of these stupendous things, and somehow Teddy did not feel, as he might have done had any other man said them, that he was in the presence of a man whose mind was deranged. There was something very convincing, very matter of fact, about the Professor. "And when I gave my lecture before the Royal Institution," he went on, "regarding the problem of reaching Mars—I suggested that it was possible and hinted that I had indeed solved the problem, but was handicapped for want of money. I received, within twenty-four hours, offers of sufficient capital to run a European War! And now, young Craig, I've got all my plans laid, I'm going to conquer Space—I'm going to annihilate Space—I'm going to bring to pass all the dreams of all the scientists. I'm going to Mars, and you, if you like, can go with me. What about it!"

Suddenly, Appleton had passed from the nonchalant Professor into the young enthusiast, and Teddy, gripping the arm of his chair, was almost numbed with excitement.

"You mean that, sir?" he managed to gasp out. "But how—it isn't possible!"

Appleton laughed.

"Ever monkey about at stinks at school?" he asked. "Ever used the telephone—ever seen an aeroplane? And you can then say that anything's impossible? I tell you. Craig, my son, that there's nothing impossible to science absolutely nothing! The only limit is our knowledge. When the first man shoved his bark boat out on to a river, he had solved the problem of navigation. When the first man flew a kite he had solved the problem of flight. And when the yellow fellow in China—that's where they say it originated—let off a squib full of gunpowder he had solved the problem of getting to Mars. It's all a matter of degree. And I'm going to Mars in a squib!"

Teddy laughed now. It all sounded so foolish. And for the first time he felt that after all Appleton was a man made mad by his own knowledge.

"But I say, sir," he exclaimed, "that's a bit of a tall order!"

"Of course, when I said a squib I didn't mean anything quite so primitive," Appleton told him. "The fact is. I've invented a new kind of rocket, which—but there, I can't tell you about it now. The point is, young Craig, are you willing to go with me to Mars—No, don't answer at once! Think about it. It's worth thinking over, and heaven knows it is a big enough thing to ask anyone to undertake. How long will you want to consider the matter? Can't give you too long, because I've got everything ready; the rocket is made. I've worked out all my calculations, and within a week from now I'm starting. So you see—"

"Look here, sir." Teddy said, flushed of face now, and trembling somewhat. "Look here, you'll probably think I'm as mad as I thought you were a few minutes ago, but I'm going to say 'Yes,' and that now. If you think I'm the man for the job, I'm your man!"

"Well spoken, and as I like it," said Appleton, reaching out a hand and gripping Teddy's again. "Now come along into my laboratory, and see whether you're a fellow who can pass the tests that I naturally have to put. If you do, and you're still of the same mind, there's an end of it—or a beginning, shall we say? You'll go with me!"

He got up and Teddy followed him out of the room, down the long passage, into what was probably one of the finest private laboratories in England. Weird and wonderful were the things there, giant retorts, amazing electric apparatus; a great telescope, and, what attracted Teddy's attention chiefly, a micro-telescope and a thing that looked like a submarine—a model, indeed, as he thought, of a submarine. It was about five feet long, and had this that marked it out as different from any other submarine, namely, windows on both sides and at bow and stern.

The Professor put him through a hundred tests so it seemed. He tested his heart, and his nerves—his blood pressure, and his oxygen requirements. And so on until the Professor said:

"You're quite normal, and you have kept yourself fit, Craig You can make the fourth of those who're going with me."

"I'm on, sir," the boy said, soberly.

"Very well, Craig," Appleton said. "By the way, where are you sleeping to-night?"

"An hotel, I suppose," said Teddy.

"Well, look here, I propose you stay with me—until we're ready to go."

"That's decent of you, sir," the youngster exclaimed.

"Not at all—you're my employee," Appleton said, "even although I'm not paying you! I'm glad you didn't say anything about payment, by the way. I've turned down fifty men because the first thing they asked was 'How much?' Here's the idea I've worked on. I did not want any man who had encumbrances. I wanted men who would go for the sake of the great Game, not just for monetary gain. Therefore, I have offered—nothing—except the chance to make history and add to the sum of human knowledge, just that chance and the risk of going out in a grand endeavour. That's big enough for me and—"

"For me, too, sir," said Teddy quietly.

"That's why I've chosen you," was the man's reply. "You don't want money—if you did I'd pay you!"

"I'm only a kid yet, sir," said Teddy. "So I've not run up debts, or gone bankrupt. As a matter of fact, I'm a rich fellow, or shall be when I'm twenty-one. That is if—if—You know what I mean!" He grinned a bit.

"Yes, I know what you mean," Appleton said. "You mean if you ever come back to this old earth? That's in the hands of the God who made us. Science, Craig, is but the study of God. Why do I want to journey to Mars? Just to make a sensation for the newspapers? No! I want to go to Mars because I am burned with a desire to know more about the infinite wonder of God!"

It was another side to his character that this amazing man was revealing, and Teddy felt a gulp in his throat as he listened to the reverent, almost passionate, voice of the Professor. He could not trust himself to speak, all he could do was to follow Appleton when the latter said:

"But come, Craig, you must he hungry!"

TEDDY CRAIG did not sleep much that night, and when he did he dreamed. Weird dreams and haunting, and always in them the figure of Appleton. And during the many waking hours, Craig was also thinking about Appleton, scientist, enthusiast, philosopher, mystic and, withal, a man. It was the humanity of him, as Teddy told himself, that had impressed the youngster more than anything, the simple humanity that counted for more than his cleverness, his genius, or his ambitions. Teddy dropped off to sleep at last with the very comforting feeling that he had found a man whom he was pleased to know, a man whom he would grow to love.

Morning brought with it a hardly contained eagerness on the part of Teddy, but as far as Appleton was concerned he was his own nonchalant self.

"Shall have to leave you alone to-day," he told the youngster over breakfast. "Have got to interview the other applicants who went off yesterday to think things over—interview them and test them, you know. When it's all fixed up I'll introduce the lot of you; then we'll be getting away down to where the—Dr—transport, shall we call it? is. There's plenty for us to do within the next few days."

"I didn't like to ask you yesterday, sir," said Teddy, "but was that submarine-looking thing in the lab the transport, as you call it? I mean was that a model of it?"

"It was, Craig," Appleton told him. "I've got another model too, but that's quite a tiny one, no more than a foot long and—and here, we've got an hour before anyone is due to call. Let's go and see it, eh?"

"Rather!" cried Teddy, springing to his feet.

"Here, I say, youngster, finish your marmalade!" Appleton said.

"Lost my appetite at once, sir." Teddy told him, with a grin, but sat down and finished the meal nevertheless. After which Appleton took him out into the garden—having previously gone up to the laboratory alone. In the garden Teddy found a tall building, concrete built, into which Appleton took him, locking the door after him. Teddy looked with amazement at what was inside, when the electric light was switched on. The building held a great glass case that seemed to occupy the whole space, while outside the case were a number of levers and switches, the purpose of which he naturally did not know.

"What is it?" he gasped.

"Watch and see!" was the reply.

Appleton took something from his pocket and Teddy saw that it was a small copy of the model he had seen in the laboratory. Breathlessly he watched the Professor open one end of it and adjust something within. After that he opened a small glass door that allowed him to place the model inside the case. Then the door was closed, Appleton manipulated a lever, all this being done in silence, and then he said:

"That case is now filled with very heavy gas to cause a good deal of resistance to the Marsobus—I've been stumped for a name, youngster, and that's what I've called it! pretty, I know, but it's true, anyway! Well, now watch; she is timed to start in ten seconds!"

To say that Teddy watched is to put it very modestly. He simply gloated as he looked with round eyes at the tiny Marsobus within the glass case, wondering what was going to happen in ten seconds. Suddenly it happened. This model moved slightly, not along the floor of the case, but upward. She tilted up her nose and rose from the floor—rose higher and higher, gathering speed; then Teddy saw her spurt upward at a higher speed. Again and yet again she did this. Teddy wondered what would happen when she struck the top of the case which, as he could see, was not, apparently, made of glass but of some dark substance.

"She'll smash to pieces!" Teddy cried, impulsively clutching Appleton's arm.

Appleton laughed.

"Watch!" was all he said, and Teddy watched tensely. "See!" the Professor said a second or two later, and Teddy saw an amazing thing happen. Instead of striking the top the Marsobus suddenly spread out a pair of tiny wings, or planes, and hovered in space!

"It would be foolish," came Appleton's casual voice, "to go to Mars in something that smashed to pieces when it arrived? Or drilled its way in, eh?"

"Good heavens!" breathed Teddy. "It's—it's—wonderful! And save us, she's coming back!"

The tiny Marsobus, turning, closed her wings, and was indeed making the return trip. She settled down before the astonished eyes of the boy. He laughed jerkily, almost hysterically.

"How's it done?" he asked, quietly, tensely.

"She's just a combination of rocket, submarine and aeroplane!" the Professor said simply. "Inside that Marsobus model, just as there are inside the real thing, are certain chemicals that explode at stated times, and generate power to drive the very powerful engines with which she is fitted. It is obvious that it would be impossible to carry ordinary fuel sufficient to do such a tremendous journey as it is to Mars! Therefore, the power problem had to be solved first. I have solved it by the discovery of certain chemicals. They take up but very little space, weigh very little, and yet are of great concentrated power."

"My hat!" breathed Teddy, drawing a hand across his forehead. "My hat! And—it—will work with—the big one as it did with this? You're sure?"

"Craig," said Appleton seriously. "I've tested this invention in every conceivable way except that of launching the full-size Marsobus. That one you saw in the laboratory has been fifty miles up and has come back again, safely and without damage. Everything has been proportionately worked out, and the altitude register showed that she went exactly fifty miles as I had primed her to do, before she opened her wings, turned, and started on the return journey. Of course, there's been a certain amount of adaptation necessary to effect the return journey without human agency in her; but the real thing will be able to hover, and remain where I want her to as long as necessary, and then to land where I want her to land. You're still of the same mind?" he suddenly switched off.

The grip of Craig's hand on his arm gave him the boy's answer, and Appleton smiled.

"Good for you, Craig," he said quietly. "Sorry I can't tell you anything more now. You'll discover everything in due course—and I wouldn't like to spoil the real thing for you by telling you too much beforehand!"

"Spoil it!" breathed Teddy. "Spoil it! Good heavens! If you told me everything, there'd be enough to keep me wondering for the rest of my life!"

"Well, wonder on, my boy—but wonder with a still tongue in your head for the next few days! Now let's get back to the house. I've got work to do!"

Teddy saw no more of the Professor until the evening, and then it was at dinner. Craig was tired out from a boyish tour of London, in which he had spent nearly all his five pounds and enjoyed himself immensely, the uppermost thought to his mind being that as Fate had willed it so, he must make the best of time while it held, seeing that he was leaving all familiar things for something vast and unknown.

It was a weird dulling thing to think of at all. There was only one thing to which Teddy could compare it, and that was when be first left home to go to school. That was like going to a new world, but this thing that he had pledged himself to do—it was something more tremendous than that. He could not really focus his mind; yet on the other hand everything seemed to have taken on a new significance. He looked up at the cold, austere column in Trafalgar Square; he had seen it dozens of times before, but it had meant nothing to him. Now it meant much—honour, glory, the tradition of his own race. Queer how he should think of that for no other reason than that he was going away from it all, when, despite all the school teaching, all the reading, that emotionless stone had stood for nothing.

From which will be seen that Teddy's mind was mazed and muddled. He was still muddled when he sat down to dinner, facing Appleton in the well-appointed dining-room, that evening. The Professor noticed his distraction and spoke of it. Teddy, needing no other urging, launched forth into a boyish exposition of his mental state, to which Appleton listened quietly until he had finished.

"You're right, my boy," he said at last. "We humans have grown too self-centred. Science is the great chastener of human pride—but, why should we worry about anything of the kind? You've had a good day?" So have I. I've found the three other men who're coming with us. One is an engineer, another an ex-airman, and the third—well, he's everything. Been a seaman down in the South Seas; went within a hundred or so miles of the South Pole, has globe trotted nearly all over the world, and is, moreover, a man of culture and education. He can give me points, too, on mineralogy. In fact, he's going to be a most useful member of the party. To-morrow we go down to Dartmoor, where the Marsobus is housed.

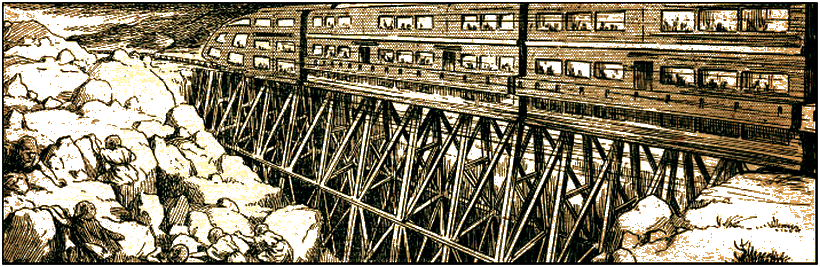

"I'm getting to bed early to-night; we've got a very early morning train to catch. I'll tell my man to call you. Good night."

Utterly tired, Teddy did not lie awake that night, and it seemed to him he had not slept many minutes before he was roused. Within an hour of getting up, he and Appleton were sitting in the railway carriage which Appleton had engaged, waiting for the three other men who had been accepted by the Professor.

They came, one by one, and were introduced. First came Mackenzie, the engineer. A tall upstanding man he was, almost as broad as long, and with a face that betokened strength of character equal to his physique.

"Pleased to meet ye, young sir," he said to Teddy, and his big hand closed tightly upon the boy's. "Craig, eh? A good Scots name, though 'twould seem ye have lived long among the Sassenachs forby that ye ha' lost the music o' the north in your voice."

"Scotch, I am," said Teddy, laughing, "but I'm ashamed to say, I've never been to Scotland."

"The finest little country on God's earrth," said Mackenzie. "Why—" He broke off as another man entered the carriage, and was introduced immediately as Robert Ashby, one-time seaman, always a globe-trotter.

He looked it, every inch of him. Sun-tanned to a coffee brown, strong-looking and healthy, with steel grey eyes that for all their customary coldness were the eyes of a man who, as Teddy knew instantly, was good-hearted and generous, and whose mouth held lines that spoke of a sense of humour.

"Appleton knows men when he sees 'em," was the inward comment the boy made; a conviction in which he was confirmed when, a few moments later, the third man turned up.

"Ah, good morning, sir," the new-comer said as he sprang in, just as the train was moving out of the station along the platform. "Almost did it in!"

"Glad you got here, anyway, Horsman," Appleton said. "These are our companions," and he introduced them all. Teddy took to Horsman immediately. He knew that this must be the ex-airman of whom Appleton had spoken. Fresh-faced, strong-chinned, well set up, and every inch of him a soldier, Horsman was one of those fellows for whom any boy might be forgiven being a worshipper.

The journey passed quickly, helped by the flow of conversation, and at last the five men alighted from the train at a wayside halt in Dartmoor. A trap was engaged, and presently they were bowling across the moors, to arrive at a spot enclosed by tall wooden fencing. The driver was dismissed, and the five men stood before the one door in the enclosure. Appleton rang a bell, and a voice beyond demanded to know who was there.

"Appleton," was the reply, and instantly the door swung open, to admit the little party. "Morning, Squires," the Professor said to the man who admitted them and who was beaming at the sight of the scientist. "Everything all right?"

"Everything," was the reply. "Just the same as usual, you know; dozens of folk peeping and prying and the talk in the villages just as usual! It's surprising the kind of things they've imagined, these country people!"

"None of them been out since I left?" Appleton queried anxiously.

"Of course not, Appleton," was the reply. "They're paid too well to want to leave and so break their bargain. And everything's ready to start when you're ready."

"I'm ready to start now," said the Professor, "but a week to-day is the appointed time, and we can't start before. By the way, these are—" and indicating his companion's, he introduced them as his fellow adventurers.

"Mr. Squires is a brother scientist, who has been in charge of things down here for me," he explained as they walked towards a great building. Coming to it, the door was opened and they all went inside, to see about two dozen men at work on what Teddy, at any rate, knew was the finished Marsobus, of which he had seen a model the day before.

No man spoke a word. They all stood and gazed upon the strange looking craft that was to take them on such a perilous adventure; and, except for the occasional clink of steel on steel, or the movement of the workmen, there was silence, until Appleton, turning said:

"We'll go and get some food!"

Two hours later they were back in the building, with intent to learn what they could about the Marsobus, Appleton having explained that he had engaged them with a few days to spare for this purpose.

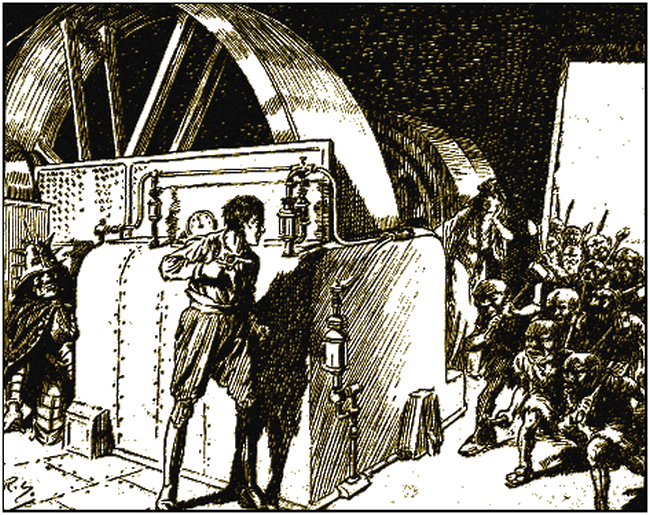

"Mackenzie," he said, when they were standing beside the Marsobus, "you know all about motors? Well, these in this Marsobus are very simple affairs, but extremely powerful. You'd better have a look over them right away. Come in."

He opened a narrow slit of a door and led the way inside. A switch was touched, and the interior was flooded with electric light. Teddy for one stood absolutely amazed at what he saw. They were in the stern of the Marsobus and the chamber in which they stood contained two pairs of motors, some big cylinders and a good many other pieces of mechanism: it was for all the world like the engine-room of an electrically driven ship. The chamber was constructed so that although the Marsobus was slanting at a very big angle, one could walk upright in it.

"There's an engine-room like this at either end," said Appleton. "Each set of motors is sufficient to drive the Marsobus, but it was a case of providing for emergencies. Here's a plan, Mackenzie. Set the motors going and see how they work."

Mackenzie, without a word, took the plan, scrutinized it carefully and after a while reached over to a switch; immediately the motors began to purr, and everyone except Appleton and Squires showed their amazement at the absence of noise.

"They do be verra quiet," commented Mackenzie admiringly, and began to move from point to point, taking notes as he examined every movement and noted every peculiarity.

"Yes, they're pretty good," said Appleton. "They're running now on electricity supplied from outside, but—cut them off, Mackenzie!" The engineer obeyed, and then Appleton moved across the chamber and disconnected a wire. From each of his lower waistcoat pockets he took out a tiny phial.

Into two funnel-like arrangements on top of one of the sets of motors he shook something from each of the phials. He did the same with the other set, and then, closing the funnels, and securing them with a lock-nut, he pulled over a lever, the breathless watchers heard a slight crack as of a pistol-shot, and instantly one of the motors begun to purr as it had done before.

"By hookey, sir!" exclaimed Mackenzie, "What's happened? What have you put in and—"

"That's the fuel to drive them," was the reply. "I've only put in a grain of each of those chemicals and yet there's enough motive power to drive the motors for five thousand miles!"

Mackenzie drew a hand across his forehead. Horsman leaned forward excitedly. Robert Ashby slapped his thigh. Teddy gaped, but Squires and Appleton smiled amusedly.

"You'll understand, at any rate, Horsman." Appleton said, "how essential it was to reduce weight, and to do that we had to find the right fuel. I think we've done it!"

"I should just think so, sir," the airman gasped.

"Ah, she's stopped," Appleton said at that moment, and the second motor started at once. "No, nothing's gone wrong; only the fuel is consumed, the two being arranged to switch on automatically, each as the other cuts out."

"And you mean to say, sir," exclaimed Teddy, "that we should have gone five thousand miles in that time! Why, good heavens, it's incredible and—"

"I told you those motors were very powerful, didn't I?" Appleton said, "I rather pride myself on their being the finest motors ever yet produced. Are you satisfied with them, Mackenzie?"

The engineer simply looked with dumb eyes at the Professor, unable to speak for a while.

"Eh, mon, but it's wonderrrful!" he rolled at last. "Forby there be other murracles aboard this boat, eh?"

"Oh, one or two," was the reply. "Come along," and Appleton led the way through a steel door into another chamber. This was fitted up in much the same way as a ship's stateroom, with bunks at the sides, and a clamped down table and chairs on the floor. "This is where we'll live while we're going," the man said calmly. "We shall exist mostly on tinned foods, though the electric cooker we've got will provide us with hot drink and so forth. Tinned stuff packs better, and after all, you can cook it, eh, Horsman?"

"We used to out in France," was the airman's reply. "Lordy, what an aeroplane this would make!"

"It is one after a fashion," said Appleton, and he explained what Teddy had seen the tiny model do. "What is that?" he echoed, as Teddy pointed to a cut off section of the "stateroom," and asked the question. "Oh, that's the wireless cabin. You see, I'm going to send bulletins down here, while we're traveling, to my friend Squires. We're going out, as you all know, as scientific explorers, and one of my objects is to establish communication between the earth and Mars. That wireless apparatus in there is one of the two most powerful sets in the world; Mr Squires here has the other set, and they're tuned to each other. All the stuff that has been written about wireless messages from Mars is rubbish, it only needs thinking about seriously to come to that conclusion, and I'm not going to explain the reasons why. But when we get to Mars it will be a different thing; it will mean that there are in Mars people speaking just the same tongue as people on the earth, having the same principles of wireless and so forth; and these things are necessary before intelligent communication can be set up. One thing I am certain of, and that is that my apparatus is efficient for the distance—and the first wireless message from Mars, if there ever is one, will be sent by that instrument. But let's go farther along! There are other things."

Dully almost, numbed with amazement, the men followed him into yet another chamber; and simply gaped at what they saw. For all manner of scientific instruments were resting on shelves, held down by steel clamps—astronomical instruments, surveying apparatus, an electric motor and many other things.

"We go to Mars not simply as explorers," Appleton said quietly, "but as carriers of our civilization; hence the reason for taking these things. We want the Martians, if Martians there be, to know what manner of people we on the earth are and—"

"Ha' ye got the guid old Book wi' ye, sir?" Mackenzie asked solemnly.

"Even so," was the reply. "Beyond there," he broke off suddenly, "is the second engine-room, similar in every way to the one in the stern. Here," he drew aside some curtains, "are windows, through which we shall be able to see. There are windows also in bow and stern. By the way. I omitted to say that those cylinders in the engine-rooms are containers of oxygen, under enormous pressure. We shall want that in here and we shall want it in Mars as well, since, as you most probably know, the air there is much rarer than on the earth, and we should, to any the least, be very short-winded! Therefore, I have designed a special mask for our use when we arrive; it is used in conjunction with a box to fit on the shoulders, much the same as the modern diver is equipped. And now, friends, the next few days will be taken up with your all getting thoroughly acquainted with the ways of the Marsobus. We start next Tuesday night!"

THE days that followed were crowded with scarcely contained wonder as new marvels were discovered about the Marsobus. If either of the four who had been engaged by Appleton had had any qualms about the venture, they lost them as these revelations were unfolded to them, and by the time that Tuesday evening arrived, everyone was eager to be off. Teddy, especially, felt as a schoolboy feels as he boards the train that is to take him to the seaside for the first time in his life.

The workmen had gone. Squires alone remained to say good-bye, and the parting between him and Appleton was affecting, even although both men smiled and spoke confidently.

"You're sure everything's all right, Appleton, old chap?" Squires asked, with a trace of anxiety in his voice.

"I tested everything myself during the day," was the reply, "You can shift the roof now!"

Squires pulled a lever and the roof of the great building slid away as a theatre roof moves for ventilation purposes. There followed a general hand shaking, then the adventurers entered the Marsobus. Appleton being the last. Once inside, he shut fast the slit of a door, and signed to Mackenzie who had taken up his stand by the motors. The engineer pulled the lever that controlled the admixture of the chemical fuel, the motors began to purr, the Marsobus trembled slightly, and the men inside heard a tremendous droning which they knew to be caused by one of the two great propellers—an auxiliary being fitted in ease of accidents, and arranged so that it should work automatically in case of failure of the other. Followed a scraping as the Marsobus drew up the steep incline on which she had been resting; then the scraping was over, and Teddy, standing at the window in the stern, saw the lights in the great building receding. It seemed to him that he saw them for but one moment, and then they were lost sight of. He gripped the rail by the window, a flood of emotions surged through him; a wave of foreboding, followed almost immediately by a feeling of exultation as he heard Appleton's voice saying:

"My friends—we're off! Our journey has begun!"

The tension broke at that, and every man of them turned and faced their leader, whose face was flushed, but who, despite what must have been his pride in achievement, was still his nonchalant self.

"May the guid God luik after us!" came a pious prayer from Mackenzie, and a murmur of "Amens" went round the engine-room.

"There is nothing for any of you to do, except Mackenzie—unless be wants you to help him at all," said Appleton quietly. "Don't forget, Mackenzie, the moment the motor stops and its opposite number starts automatically, you will replenish it with fuel, so that it is ready to take up the work. Don't spare oil anywhere. Craig, come along with me to the wireless cabin. Horsman, and you, Ashby, potter around and please yourselves!"

"I'm staying here, sir," said Horsman, "I want to watch the stars go by! Do you know, sir, it's the rummiest thing out to be flying without feeling the rush of the wind in your face. But it's good—good for the soul! It's a wonderful world we live in!"

"Wonderful indeed!" said Appleton, as he moved away with Teddy at his heels. The Professor went into the cabin, and at once jotted down something in his diary.

"The exact time of starting, Craig," he said. "And now to wireless down to Squires!"

He adjusted the earpieces as he sat at the table, and for the next few minutes was silent, as he worked the mechanism of what he had called the most powerful wireless installation in the world. Presently he looked up.

"I got him," he said. "There's a terrible to do on the earth. That propeller of ours was too noisy—it awoke half Dartmoor. I think, and the whole of Britain is already, at this time of night, too, alive with the news of some tremendous airship that was flying over the country and has gone as quickly as it came. I've told Squires that he can now send round word of what is happening, and I bet that by the morning there'll be many strange things said and written—chiefly that Squires is a liar! Afraid it's going to be a bit monotonous on the journey, Craig!" he switched off, as was customary with him.

"It isn't up to the present," said Craig. "But then we haven't been any length of time yet!"

"No, but we've covered many thousands of miles!" said Appleton. "And if everything goes as smoothly as it is now, we'll not have any cause for anxiety. That's why I mean it will be monotonous. Still, we've got a good library aboard and I dare say, what with the books, and the gramophone and an occasional game of chess—play chess? good—we'll while away the time all right!"

Appleton was a little too confident and although there is no intention here to tell the complete story of that journey to Mars, the purpose being to recount, from Appleton's own account, the story of the sojourn on the planet, one or two of the several things that served to break the "monotony" must be told.

There was, for instance, the moment when it seemed that the end had come. That was when the Marsobus, having got far beyond the sphere where the gravitation of the earth had any attraction and Mars itself was acting as a pull, there was seen whirling through space a mighty glowing orb. Instantly Appleton, without a word to his companion, sprang to where a map of the heavens hung, and examined it very carefully. He turned presently and said, in a low voice:

"Men, I ought to let you know that there's danger ahead of us. That ball of light is not on the map. It is a stranger to me, and I've studied astronomy for years. It must be an undiscovered comet, and as far as I can judge we shall drive straight into it! I'm sorry that I—"

"Don't!" exclaimed Horsman, springing to his feet and letting the gramophone scratch unheeded at the end of the record. "Don't! We came of our own free will. And we've only got to die—once!"

"Hear, hear," came a low murmur from the rest, as they crowded at the window in the bows, and watched the long-tailed comet sweeping through space. It seemed it must cut right across their path.

"We—can't steer the bus," come Appleton's voice! "I—worked—out the—line—of—direction—and there's no—changing it."

He was looking through a telescope as he spoke, adjusting it to keep the comet, within the field, and quickly putting down certain marks on the paper beside him. For a moment or so he took his eye from the telescope and was busy, apparently, working some problem maths. Then once more he got back to the instrument, only again to dash off a maze of figures, and at last, to look round, his face pale and haggard, and to say:

"Thank God—we shall miss it, after all, by a thousand miles!"

And then, the ball of light suddenly seemed to become an iridescent flood, blinding to the eyes that watched. Thousands of miles away it had been . . . then—then, to the watchers it appeared to be but as many feet—for the Marsobus was bathed in its great effulgence. The men inside closed their eyes involuntarily, expecting they know not what. Then they opened them again, wonderingly, unbelievingly, and knew on the instant that they had passed the menace.

It took a very long time for the adventurers to recover from the shock of those tense hours, and it was lucky indeed for them that during that time nothing untoward happened. It was a long while afterwards when their nerves were steadied by a monotony that, would, in other circumstances, have driven them crazy, that another incident happened fit to awe them. Of a sudden the working motor stopped, and the companion to it did not act as it was supposed to do; with the result that the electric light failed.

"Mackenzie!" Appleton roared. "Where are you," and he himself made a dart through the door, in the direction of the bow motors.

"Here, sir!" called out Mackenzie—and scarcely had his voice died away than the lights went on again, and the anxious men heard the soft purr of a motor. They crowded into the auxiliary engine-room, and there saw Mackenzie, sweat standing in beads upon his forehead, leaning on the wall for support.

"Oh, good man, good man!" breathed Appleton. "You remembered!"

"Ay, sir," said Mackenzie feebly. "I happened to be here when the lights went out an' I did guess what 'twere happening. So I turrrned these motors on and switched over."

"Listen men," said Appleton, as calmly an he could, but he too was like a man with the ague. "There is no need for us to get alarmed over anything like that happening. From now on we could go to Mars without any motive power of our own: Mars is drawing us—the earth has nothing to do with us at all. We only need the motors for speed—it's speed we want. Mackenzie, get you away and see what happened to that motor."

"Ay, ay, sir," said the engineer, who was now recovered. "It may be all right, but I hope it doesn't happen agen!"

His hope was fulfilled, for although there were various other things that did happen, with which we have no time to deal here, the motors did not fail them any more, and at last the time came when Appleton, issuing from the wireless cabin, said to them all:

"Men, we have just got through the last wireless to Squires before we reach Mars. Come with me!" He led them to the bow window and pointed out what seemed to be a chequered black and white and red globe. Large indeed it was seen even through the naked eye. Through the telescope it was a thing to wonder at.

"That is Mars," he said quietly. "Every man will at once put on his mask and his oxygen container. Mackenzie, when we have done that, you will stand by the motor, ready to obey my instructions."

"Ay, ay, sir," said Mackenzie, and within ten minutes every man of them had on his mask and was standing by, wondering.

What happened was that Appleton, standing in the bow of the Marsobus, suddenly pulled a lever, and the Marsobus, which all his companions had quite expected to crash into the solid forbidding mass that swung in space before them—the mass that they knew was Mars—seemed to tilt up at a higher angle, and they were looking out of the windows down upon the most amazing sight that had ever greeted the eyes of man.

"Open the window—snap it quickly!" came Appleton's voice, and Horsman, who had been appointed the photographer to the party, obeyed, and so was taken the first photograph of Mars as it actually is.

THE Marsobus hovered over the planet, within a thousand feet of the surface. The men inside her stared fascinated, feasting their eyes upon the scene, more conscious than they had been before of the absence of the upward "lift" of the Marsobus. Ever since they had got within the gravitational range of Mars the "going up" impression had been replaced by what Horsman had called the "nose-dive," and half the airman's emotions had been the result of that impression, which brought back recollections of experiences through which be had passed. He it was who had heaved a sigh of relief when the great wide spreading planes of the Marsobus opened.

Chief of all emotions, however, amongst all the members of the party was that aroused by the close vision of Mars itself. During the long journey Appleton had entertained his willing listeners with theories regarding the planet: theories that were well worn, and theories that he himself had formed by independent study of the planet. Questions of the canals, of the ruddy colour of the planet, as seen through the telescopes of the earth: questions of the polar caps; of the likelihood of animal and plant life—in fact, all the problems that had for centuries perplexed humankind regarding Mars had been discussed, and, naturally, all had been conjecture.

But now they were face to face, as it were, with reality, and it was vastly different from anything they had ever conceived. True, Appleton himself had for a long time been making observations through his telescope and microtelescope, but for some reason he had told nothing of what he had discovered—evidently wishing to keep it all as a surprise. The unskilled eyes of the other members of the party had told them very little of value, except Horsman, that is, whose flying experience had taught him observation and given him the facility to interpret what he saw. Nevertheless, even he could not restrain the exclamation of surprise at what lay beneath them.

"By Jove!" he exclaimed. "Look, young Craig!"

Teddy was looking; he needed no inciting to feast his eyes upon that scene, any more than did the rest of the party, including Appleton himself. Below them lay what reminded them of nothing so much as cities of an ancient civilization—of Egypt, of Assyria, of the wonders of Aztec cities, that lie now just relics of the great past. With this difference, that so far as the eye could tell at that distance, the buildings were not of stone or brick but of metal—some metal that shone like gold and threw back the sun's rays in scintillating beauty. The city covered, literally, a great island that lay on the bosom of a vast lake, fed, as could be seen from above, by a straight cut channel that came from somewhere in the unseen distance.

"Got it, Horsman?" came Appleton's voice, suddenly cutting the deathly silence that reigned, and the young aviator pulled himself up with a jerk.

"You bet!" he said. "And more than once I almost dropped the camera back to earth!"

He laughed a little hysterically, but Appleton said, quite calmly and seriously, as though he were lecturing a company of students.

"Don't be foolish, Horsman! If you dropped it it would fall on Mars, not on the earth. And—" he was peering through his powerful glasses as he spoke, and pulled up shortly. His face was pale, his mouth firmly set, and not even the hideous mask that he wore could hide the fact that he was greatly excited. "There—are—people—something like—people—moving—about—down there," he said. "Friends, we've solved the mystery that is eating the hearts out of scientists on the earth." He literally dashed away from them and ran into the wireless cabin; the rest followed him and the Marsobus, stationary now, hovered uncannily as Appleton had fixed her to do. With nervously twitching fingers, all his old sangfroid gone now, Appleton worked the wireless instrument. Calling . . . Calling . . . Calling . . . and wondering whether the answer would ever come.

It came at long last . . . And Appleton, almost weeping for very joy and sheer excitement, sent the whispering waves careering through the eternal space, carrying to Squires the message of the great achievement.

"The world will know within five minutes!" Appleton said huskily, as he got up from his seat. "Heavens, what I would give to be there to know what happens, to witness it all and to—to . . . sorry, fellows," he recovered himself quickly. "I'd rather be here than anywhere else in God's universe. We'll descend. Automatics ready, in case of trouble. But no one to act until I give the word!"

Pent-up with excitement, with every nerve at a tension, with strange beatings of hearts, every man took up his post as prearranged, while Appleton went into the bow and sat in the pilot's seat. The hovering Marsobus seemed to spring to life as she answered to the call of her master and the next moment was volplaning down to Mars.

"What the blue jinks is that?" cried Mackenzie suddenly, and he seemed to have his eyes glued to his glasses.

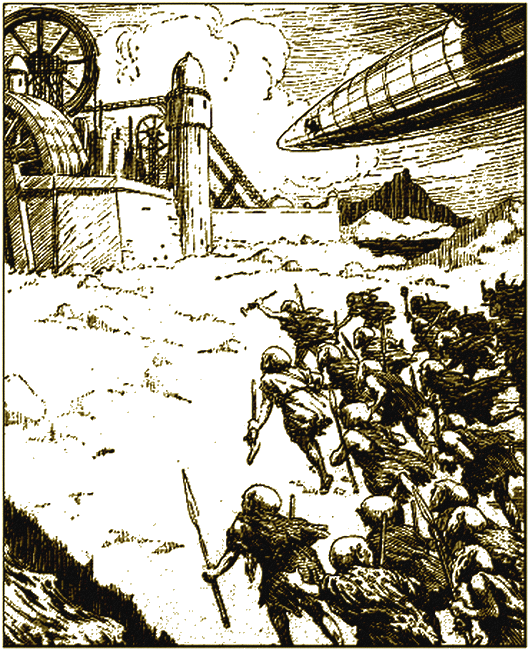

"Where? What?" came the chorus; but there was no need for Mackenzie to say any more, because everyone saw what he meant. Rising from the flat top of a great building was what looked like a flight of birds—tiny things that flew with flapping wings.

"We've scared some birds, I reckon," said Ashby; but Appleton said quietly, grimly:

"Not on your life; those things are—aeroplanes! And they're coming for us!"

"My word!" breathed Horsman. "You're right, sir. What are we up—a thousand feet? And they look no bigger than pheasants even at that distance!"

Straight for the hovering Marsobus the strange flight was coming, and although the earth-men themselves were in a machine that could operate on the helicopter principle, they were not a little amazed to notice that the aeroplanes—for the nearer the things came, the easier it was to see that they were indeed aeroplanes—were rising vertically, and their wings were moving up and down as they came.

"The thing is, shall we wait and see what happens, or shall we make a beeline for the lake?" Appleton muttered, as if to himself. The problem was solved for him by the first "squadron" of aeroplanes reaching the Marsobus and rising above her, and Appleton, thinking discretion the better part of valour in circumstances of which he knew not the full purport, decided to make for the lake. He called out to Mackenzie to see to the motors and, seating himself in the pilot's cabin, manipulated his switches; the Marsobus moved forward, and the uprising aeroplanes were left behind.

"They're bound to chase us, but that won't matter, perhaps!" Appleton said.

Teddy, standing beside Appleton, saw the long thin line of his compressed lips, and suddenly realized that something was wrong.

"What is it?" he asked huskily, but for a moment or so Appleton did not answer. When he did it was in a voice thick and choky.

"The wretched thing's got out of control!" he said. "I can't steer her. I wanted to land yonder on the lake, but she's heading straight for the heart of the city and—and—Craig, I'm afraid our adventure is going to end in disaster! Tell the others! It's only fair to let them know what's likely to happen."

Teddy rushed to do his bidding, but there was little need for him to have done so, since Horsman, standing at the window, had seen what was happening.

"It's rotten luck, Teddy," the airman said; "but—it's the fortune of adventure! And, anyway, we may escape a proper smash, and—"

His words were drowned in a terrific crash that shook the Marsobus from end to end and threw her occupants to the floor. Teddy picked himself up wonderingly; he saw Horsman lying huddled in a corner on top of Ashby, and Mackenzie came tottering, gropingly, through the door from the stern engine-room, his face smothered with blood; he was blinded by the red flow over his face.

"What's happened?" the Scotsman asked falteringly.

"It's all right, fellows!" came Appleton's steady voice at that moment. "We've hit Mars—hit it full; but thank goodness we're not smashed up."

Teddy turned to him, but Appleton slid across the floor to where Horsman and Ashby lay. He turned them over and examined them, forced some brandy between their lips from the pocket flask he carried, and said not a word until he had brought them round.

"Only stunned," he said at last, when they were on their feet. "Now listen, fellows; we're in a bit of a mess. We've crashed right through a terrifically tall building—domed like St. Paul's it is—and the nose of the bus is sticking in, and there's a sight worth seeing. Come along."

They followed him into the pilot's cabin, listening as he told them that just as the Marsobus struck the building he got control of her, but not in time to save her from boring her way through.

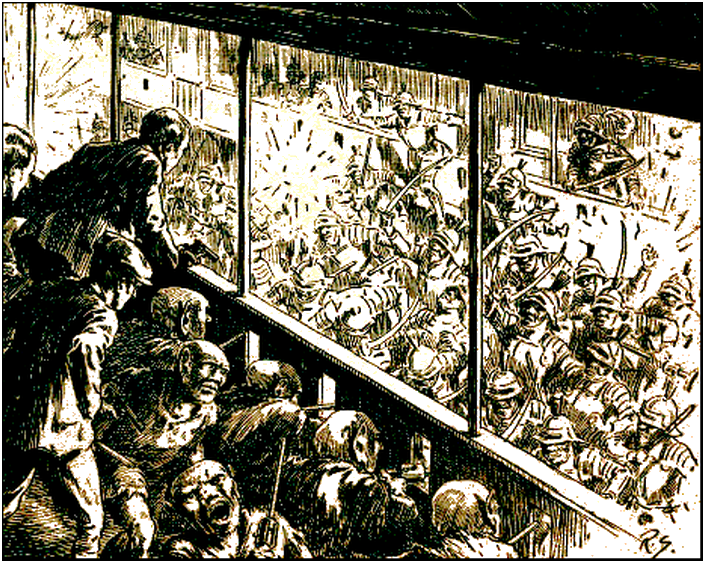

"Look!" he said, and they looked with wondering eyes. Down below they could see, bathed in a white light, a temple like building, with hundreds of people flitting to and fro as if in terror, while on a throne in the centre sat a gigantic man, armed and armoured like a knight of ancient times. He was evidently trying to control the disorder, and even as the earth-men watched they saw that he was succeeding, and they saw something else. Up stairways in the sides of the building tall men and little men were racing, going from one gallery to another—the whole building was lined with these galleries right to the very top—and it was evident that these men had been ordered, and were proceeding, to do something to the strange intruder into their temple or hall, whatever it might be.

"I'd like to know what they're going to do," Appleton said calmly; "but I think we'll not stay. Fortunately, we're stuck in the roof of this building, but the engines are working, and I'm going to reverse and wrench the bus out. Mac, if you can see, set the engines going—the stern set. The rest of you hang on to anything, in case of accidents!"

But before they could do so there came a sound of hammering on the shell of the Marsobus—great heavy reverberating blows.

"Those fellows have not only got aeroplanes, but bombs as well!" called out Horsman excitedly; he was actually feeling in his element now.

"They've got to have a better explosive than any there is on earth," said Appleton, "if they are to get through our hide. As I told you, the bus is made of a metal that I invented myself, and there's nothing I know that can punch a hole through it! Hang on—we're moving now!"

That was not exactly correct. What was correct was that the Marsobus's engines were purring away, and presently there came the sound, above the constant hammering, of the bus tearing herself away from the great jagged hole she had made in the roof of the building. The engines, the most powerful ever constructed by man, made short work of the task, and suddenly the Marsobus shot—literally shot—like a rocket from the imprisoning roof. Instantly Appleton changed the direction of drive; then, with the Marsobus under control again, he turned its nose straight for the spreading lake that he had wanted to reach before the catastrophe.

"Thank goodness!" he breathed to Teddy, standing by his side. "It's rotten luck we've made such a wretched debut, but it can't be helped. We'll have to make the best of it. My word, even although nothing's coming in, those bombs or whatever they may be are giving us a shaking up!"

The Marsobus, instead of swinging on her even way, was rocking every now and then as something struck her and, since the windows had been closed, it was impossible to see what was happening outside. Actually what was happening was that a larger swarm than ever of the tiny aeroplanes was chasing the Marsobus, but their speed was as nothing compared with that of the bus, which Appleton, taking his bearings through the very small observation window in the pilot's cabin, was guiding towards the lake. At last, not without some trepidation, of which he made no mention however, he managed to bring her there.

"Look here, fellows," he called out then, "we've got to take the risk. We're going out. But before we do so we'll have a look and see what's happening to those aeroplanes."

The windows were unshielded again, and, to the surprise of all, not a sign was to be seen of any of the planes—not a sign, that is, of any still in the air; but, lying rocking on the surface of the lake, and being carried along by a current that ran through, were several of the tiny machines.

"Evidently we biffed into some of them," Horsman said grimly. "Like knocking flies down!"

"It's a pity—a great pity," Appleton said quietly. "I'd give anything for this not to have happened; but—we'll face the music. Ready?"

Leaving his seat, he went up an uncoiled rope ladder, manipulated the mechanism above, and so opened the sliding panel that gave exit to the open air. A second ladder already attached was pulled up and flung outboard. Appleton clambered down it and hung like a mariner in the ratlines, looking out across the water to the City of the Island.

"Come up, comrades!" he called out, and at the word the rest scrambled up and poked their heads through the aperture, with no eyes for the ice-covered shell of the Marsobus; no eyes for anything but the vision that lay before them. Swarms of living beings lined the edge of the island nearest to them, gazing with as much wonder on the visitants as the latter gazed at them. Giants there were, and yet not all of them were giants, for some amongst them were of a size that made the Britons feel like giants themselves; and nevertheless it was possible to see, even at that distance, that the smaller people were not merely children, since some of them boasted beards.

And all of them gesticulated wildly, while from the inland came a low murmur of voices.

"The Martians!" breathed Teddy through chattering teeth, for the air was chill and almost numbing.

"Ay, ay, the Martians," echoed Appleton. "We must go to meet them. Get out the boat, Mac!" and Mackenzie dropped off the ladder and handed up the collapsible boat with which the Marsobus was equipped. Appleton took it and lowered it on to the surface of the lake, released the spring that held it closed, and within a few minutes every man of the adventurers was aboard her, with Mackenzie rowing lustily towards the shore of the island and Appleton sitting calmly in the stern, watching the movements of the Martians. What was to be their reception?

Suddenly the Martians passed from their evident astonishment into some state that held something more sinister for the visitors. A large number of them went streaming back to the city and lined what seemed to be a huge embankment; there came floating across the waters the sound as of a hundred bells, and at each clanging note still more people sprang upon the parapet until it was literally alive with moving figures.

Those who remained on the shore—the pigmies these—stood as impassive as if they were carved out of stone. There was nothing hostile about them; they merely stood as though they would welcome the new-comers, or perhaps it was that they were waiting for orders.

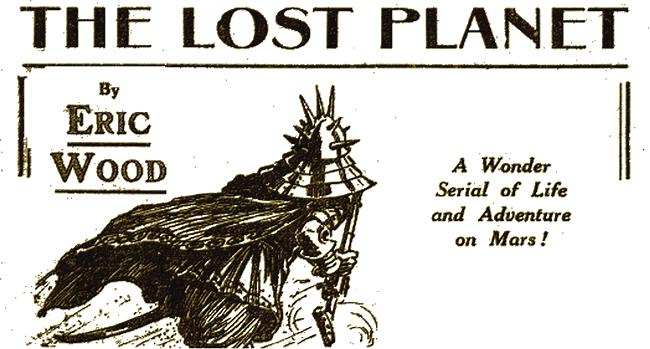

Presently, there issued from the city a massive figure of a man—one whose height and bulk seemed to dwarf the largest of the rest. A horned helm he wore with glittering points at the end as of diamonds flashing in the sunlight, and he looked for all like a Viking of ancient days. He strode down to the shore, and the pigmies there bowed till their heads touched the ground; they remained thus until with a loud voice the new comer shouted something. Then they sprang erect; every man of them put his hand into the skin tunic that he wore, took it out again, seemed to throw something into the water and the next instant not a sign of the Martian city, of its teeming peoples, of the pigmies on the shore, or of the man who towered so majestically amongst them, was to be seen.

And more than that, the occupants in the boat that had set off from the Marsobus could see neither one another nor the vehicle that had brought them from the earth. The light of the sun was blotted out; there was a dense, unyielding pall of blackness, as black as the darkest night.

"Steady, men!" came Appleton's voice, followed by the "splash" of his powerful electric torch. "Torches out, all of you!" And four other torches smashed into the darkness, only to spread out as though they were focused upon a solid wall. Penetrating power there was none.

"Worse—than—the—gas—of— Flanders!" came Horsman's voice huskily.

"Thank Heaven it's not so bad—it doesn't choke!" exclaimed Appleton. "I shall have to find out how it's done!" He was speaking quite naturally as though he were discussing some scientific experiment that was entirely new to him.

"What are we going to do, sir?" Mackenzie asked. "Shall I keep on rowing or—"

"What's the good?" Appleton told him. "You might crash into something. Lay on your oars; we'll wait and see what happens. I have no doubt our friends the Martians have something else up their sleeves!"

They had indeed!

And it happened with startling suddenness. Even as Appleton finished speaking, his torch dropped from a nerveless hand and every one of the party experienced the sensation that had preceded Appleton's own inertia; they drooped like wilting flowers and tumbled into the bottom of the boat.

TEDDY CRAIG opened his eyes with difficulty; the lids seemed to be heavily weighted and the effort was filled with pain. So, too was the actual opening, for a blaze of terrific light seemed to burn into their very sockets and he closed them involuntarily.

The first impression was of freedom from the restraint of the oxygen masks, and for a while Appleton, at least, lay wondering how it came about that he was living at all, or, living, how it was he had no difficulty in breathing. He pondered for a while, then gave it up, with the thought, "Suppose they've solved the problem of atmosphere—find that out later!"

"Where are we? What's happened?" Craig's voice came. He spoke as though his throat were paralysed. He tried to raise himself up, but could not—except his head, which he was able to lift a little way from the ground. It enabled him to see that the rest of the party were there, too, all lying as he and Appleton were.

"'Lo, young Craig," Appleton said, "Can you get up?"

"No," the youngster told him.

"Neither can I!" Appleton said. "The rummiest thing I've struck. I can see that I'm not bound, and I know I'm not staked down—but I can't lift a limb. The only things I can do are to lift my head a bit and speak."

"Same here," came a deep growl from Mackenzie. "Seems as though I'm hypnotized!"

"Or fossilized!" said Appleton grimly. "Absolutely no feeling in my body. Anyway, it's something to the good that we haven't been killed! And that the blackness has gone. We must have been here a long time, because it's not daytime now; that's moonlight shining through that hole in the top of this place. Wonder what happened to the bus? If those Martians have done anything to it we're—we're stranded in Mars for life!"

"Lordie!" exclaimed Mackenzie. "It's verra likely that we're stranded here for life, even if they've done nothing to it at all. Bodies who can do what they've done to us won't be likely to let us gang our ain way! By hookey, but I've got pins and needles in my richt foot!"

Teddy found himself laughing at the oddity of it all, despite the fact that there seemed so little at which to be amused. He turned his head to look at Mackenzie, and in doing so found that he was able to move much easier than he had been before, and the truth came to him that whatever was the influence under which he had been placed it was leaving him.

"Things are getting easier, sir," he said to Appleton, and the Professor grunted:

"So they are, so they are; but it's infernally uncomfortable. Pins and needles, you call it, Mac. It's like red-hot hypodermic needles all over my body. But it's a top-hole anaesthetic these fellows have discovered," he went on, with a touch of admiration in his tones.

"I'd rather have the toothache for life than get my system filled with it any more," growled Horsman. "What are we going to do when—hallo, here's someone coming!" He broke off as a blaze of light shot into the place in which they were lying. It seemed to have no source, that light, but simply happened, and the whole building was lit up as brilliantly as if the sun were shining.

Sounds as of steel-clad feet clinking on stone, and the murmur as of many voices, broke the still silence. With heads raised up, the little band of prisoners, held by invisible bonds, stared at the scene being enacted before them.

Now that the light was with them, they saw that they were in a great domed building, circular and galleried right up the sides, and in the centre of the roof was a wide opening through which the moonlight had come. In the middle of the floor space, directly under the roof opening, stood a gigantic throne-like erection, that shone like burnished gold and threw back scintillating beams as though the light were reflected from a thousand gems.

"Phew!" breathed Teddy.

"Shut up!" growled Appleton. "You distract my attention!"

It was indeed an occasion for one's wholehearted attention; for, marching around the great hall, were files of men, clad in armour, every one of them, but weaponless, as far as the prisoners could see. At every few yards, parties of the men left the marching files and began to climb stairways that led to the galleries above, and, breathless and wondering, Appleton's party watched them as they ranged themselves around, until every gallery was filled with the armoured men. Then the clinking of feet on the stone, the breathing of men, the murmur of them, ceased, and deathly silence reigned again, while every man of the Martians stood tense and as if expectantly, looking steadily at the throne.

"Waiting for his nibs the boss," came from Ashby, and at the unexpected inanity his comrades laughed. The sounds of their voices seemed to whip the silence. The Martians were evidently surprised, for there was a clatter as of metal rubbing metal; it was caused by the sudden jerking of the men into movement, their armour touching as they moved. Then silence again, and the next instant Teddy saw a man sitting on the throne. How he had got there Teddy did not know. He had seen no movement. No one had crossed the hall; the man might have appeared out of nowhere, unseen in his coming. He just happened.

It was easy to see that, despite the fact that he too was arrayed in gleaming armour, he was the man who had stalked down to the shore and given the signal that had made the Martians do that which had brought about the solid blackness in which the adventurers had been engulfed. He was a giant of a man, quite seven feet in height. Red hair curled close to his head, and his face was red-hued. Human, he looked, yet in a vague, indefinite way. His ears were disproportionately large, relative even to his large stature; his nostrils were spread wide across his face, and the mouth below was also wide. The eyes were set deep beneath a beetling brow, and Appleton, at any rate, with a scientist's observation, noted the breadth of forehead and the shape that told of well-developed mentality.

The armoured men in the galleries stood stiffly at rest, the visored head of every one of them turned towards the man upon the throne. Suddenly he raised a hand, and, before the captives realized what was happening, they felt themselves jerked up by their shoulders and set upon their feet. Men, evidently behind them ready for their part, had sprang forward, and now ranged themselves as if they were a bodyguard.

"That's better, verra much better," growled Mackenzie, stamping his feet on the ground. "Why, mon, I can feel again!"

"So can I," said Appleton. "Listen, men: do nothing foolish. We're in a tight corner, and how we're going to get out of it goodness only knows."

"If so be as an automatic is any good—" began Ashby, slipping his hand to his belt, but Appleton cut him short with:

"I'll shoot the first one of you who fires without I give the word!"

"You're the boss—go ahead," said Mackenzie grimly. "Look out; his mightiness is beginning the service! Lordie, what a little voice for a big man!"

It was indeed a small, weak voice with which the man upon the throne was speaking.

"Big ears and broad nostrils and small voice—all the result of the attenuated atmosphere," said Appleton quietly, as though he were addressing a class of students. "Evolution moulds to circumstances, y'know."

"Pity it didn't teach these fellows English," said Mackenzie. "I'd give a lot to know what the gentleman is sayin'. It may be verra serious."

"We'll know soon enough, without understanding the language," said Appleton grimly. Then he fell silent again, and the Martian went on talking in the ridiculous falsetto voice, but for which there was a grim ominous silence. Presently he ceased, and the men on guard over the prisoners suddenly seized them and led them towards the throne, halting them at its very foot. It was a queer sensation, that of walking; it seemed to the earth-men as if they could not keep their feet upon the ground. Every time a foot touched the floor and the spring of it enabled them to walk, they went up with a bound. They had all been prepared for this, knowing that the lower pressure of the Martian atmosphere was responsible.

In silence they stood there, waiting.

The man on the throne leant forward and said something to them, but Appleton shook his head.

"Sorry, but I can't, understand you!" he said, and at the sound of his voice, three or four times the power of the Martian's, the man on the throne jerked upright again. It was evident that the boom of Appleton's voice, echoed and re-echoed in the domed building, had astonished him, even as the weakness of his own had been a cause for wonder on the part of the adventurers.

As he spoke, Appleton was swinging a kit-bag from behind him, and, opening it, took out a many-folded square, which Teddy recognized as the astronomical chart over which he himself had pored more often than once with Appleton during the journey in the Marsobus. It was nothing more nor less than a chart of the heavens as conceived by Appleton from the point of view of a watcher on Mars. It was a blue chart, with the stars, the earth, and moon, and the other planets picked out in white, with a thick line drawn from the earth, and on it a beautifully clear drawing of the Marsobus. With the chart spread out upon the floor, Appleton drew his finger along the line on which the Marsobus was drawn, and said, not because the Martian could understand, but because it was natural to speak as well as to motion:

"Thence have we come!"

He dived into the kit-bag again, and from it took out a large print, which was from a negative that he had taken during the journey. It was a photograph of the earth, and had been taken with the fine microtelescope on the Marsobus.

Teddy, watching Appleton, saw him point, first to the dot on the chart representing the earth, and then to the photograph, as though to make it quite clear what he meant. From Appleton Teddy looked up to the Martian, and it was plain that he was very much impressed. Plain, too, that he had some glimmering of the meaning intended to be conveyed to him by the man whose finger was tracing the lines of the chart.

He spoke—but fruitlessly as far as the captives were concerned; but his own people understood what he was saying, for they seemed to be exceedingly excited. Apprehensive, the captives watched them what time their gaze was not fixed upon the man on the throne, eager to get some inkling of his intentions. His face was impassive.

"Keep quiet, you fellows," Appleton warned his comrades; but Mackenzie, with a growl, said:

"Ef his lord mightiness did but have an accent as Scotch as his hair is red, I wad like it better!"

"Shut up, you ass!" snapped Appleton, as the Martian held up his hand. The noise subsided immediately, and the Martian spoke again. This time the effect was to bring forward, from somewhere behind the prisoners, half a dozen men, venerable with age, and garbed in long flowing robes of golden cloth, decorated with precious stones.

"The wise men!" breathed Appleton. "And they're thought more of in Mars than they are on earth!"

Teddy could not forbear a smile at the Professor's words, but the smile quickly passed in his interest to see what the new-comers would do. They approached the throne and stood before it, not as menials, but as men who had a perfect right. One of them spoke, and the man on the throne answered, pointing as he did so to the chart which Appleton still had opened upon the floor.

Immediately the "wise men" bent down and examined it closely. Appleton was quick to seize the opportunity; he seemed to sense what was happening and, bending low with the Martians, he proceeded to do for them what he had done for their king, if king the enthroned man was. Tense silence reigned for a while, but at last it was broken by one of the men straightening himself and so addressing the king.

Despite the fact that they knew no word that was spoken, the captives caught the intonation in the man's voice and realized that he was greatly excited, and his constant pointing, first to the captives and then to the chart, proved that he was explaining in his own language what he had learned from the examination made. Moreover, after a few moments, he turned to one of his companions, and said something to him that sent him hurrying away. He passed behind the throne, and the earth-men did not see whither he went beyond. He returned presently with two huge Martians following him, carrying something that, to the amazement of Appleton and his comrades, seemed to be a globe of the heavens, made evidently out of gold and with the stars and the planets, the moon, and the sun shown by precious stones!

"My word!" breathed Appleton, whose curiosity overcame him, so that he advanced to meet the Martian, who ordered the bearers to put down the apparatus and then waved them aside. The man on the throne leant forward expectantly, and listened intently while the wise man spoke, illustrating his words by reference to the globe. For a long, long time he spoke, and when at last he had finished the King stood up on his throne and said something in a loud voice. Immediately the Martians in the galleries began to move. They descended to the floor of the hall, and marched out, leaving the earth-men with the king and the wise men, and the few others who had acted as guards.