RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Gustavo Simoni (1845-1926)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Gustavo Simoni (1845-1926)

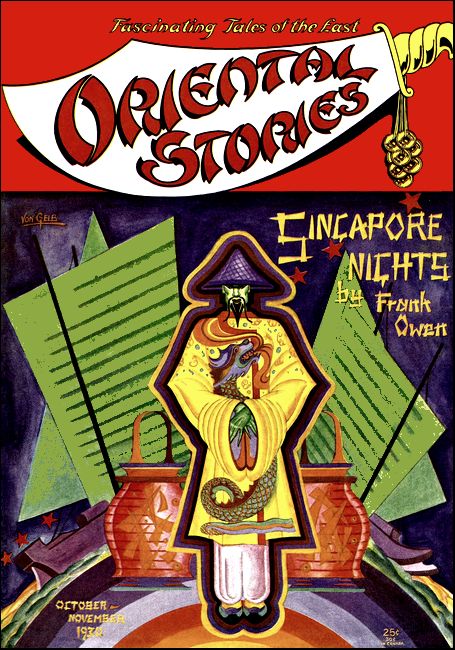

Oriental Tales, Oct-Nov 1930, with "The White Queen"

IT was Bishop Fergus who suggested that his daughter's future should be staked on the hazard of a chess game.

"But that is gambling!" cried Fenworth, appalled. "Why not let Constance decide the matter herself? She is the one most vitally concerned."

Bishop Fergus looked over the side of Granby's yacht and stared meditatively into the Persian Gulf. His massive, nobly molded face and chiseled forehead, aureoled with an ample crop of snowy hair, looked like the carved bust of a Roman senator. Apparently he was lost in contemplation of the sand riffles on the bar that held the yacht fast a hundred yards from the Arabian shore, but in reality he was deep in thought. He twirled his spectacles absently by the black ribbon that held them. With his left hand he rubbed his smoothly shaven chin.

Suddenly he whirled around and faced his daughter, who was gazing at him with a world of entreaty in her eyes. He glanced from her to Fen worth, back to the girl, and looked at Fenworth again.

"Constance is only nineteen," he said. "She can not possibly know her own mind, and she is altogether too young to marry."

"But Father—" Constance interrupted.

The bishop raised his hand and continued hastily:

"No, no, do not break in. Hear me out, for, after all, I am your father and whatever I do will be with your best interests in mind.—Fenworth, you loved Constance before ever you came on board. If I had known that before we left San Francisco, then you never would have started. When old Granby placed his yacht at my disposal for a trip to the Holy Land, and you asked to go as my secretary, you kept to yourself your love for Constance. That was dishonest. Oh yes it was, Fen worth! You knew I never would take you along if I had suspected such a thing. But we had not been on the ocean two hours before I saw how matters stood.

"I like you, Fenworth, in every capacity except that of son-in-law. Now that you have come to me and asked for my consent, I could refuse to give it, but I must have your acquiescence. I must not be opposed in this matter. That is why I am putting it to the test of a game of chess. You have boasted of your prowess. I, too, am a chess-player, although I have not touched a piece in twenty years. There is a chessboard in Granby's cabin. I will play you one game. If you lose, you must break off this foolish love affair at once."

"And if I win?" Fenworth faltered, disquieted.

The bishop shrugged his shoulders impatiently.

"If you win I shall cease to oppose you, but I can't promise to co-operate."

Fenworth scanned the bishop's face, without answering. The bishop averted his eyes, and continued nervously twirling his glasses.

"Come, come," he said at last. "Will you play?"

"But that is gambling," Fenworth repeated again. "You are a bishop."

"Chess is never gambling, no matter what is at stake," the bishop affirmed. "Chance plays no part in it, for it is purely a game of skill. You are a good player, are you not?"

Fenworth did not reply, but continued to stare into the bishop's face.

"Much better than the average, I take it," the bishop continued, with a suggestion of sarcasm in his voice. "A really fine player, perhaps?"

"Father!" Constance admonished him.

The asperity in his voice amazed and wounded her.

"An uncommonly brilliant player, I believe?" the bishop continued, not heeding his daughter's interruption.

"Yes, sir," Fenworth answered, nettled. "I think I may say so without boasting, if past achievements prove anything. I am the best in the chess club. I won the intercity trophy two years running."

"Very good, then," Bishop Fergus continued, smiling blandly and rubbing his hands together rather gleefully. "In that case, it would seem that I am taking all the risks, and you none. Bring up the board, my boy. You will find it behind the book-shelf in Granby's cabin, and the chessmen are in the table drawer."

His face beamed as he saw Fenworth disappear. Not for weeks had he seemed so happy.

"Father, you mustn't," Constance pleaded.

"Constance, please do not oppose me," he ordered.

A HUGE red, green and yellow umbrella was put into place on

the deck, and Fenworth sat down in its shade with Bishop Fergus

to play for the bishop's daughter. The sky-blue water lapped

gently against the sides of the yacht, and the hot sun rained its

rays upon the yellow sand of the desert, a scant hundred yards

distant. Not a sound broke the stillness, except the droning of

the desert flies, for the boat's machinery was stopped.

The position of the stranded yacht had been wirelessed, and help was on the way from Muscat. To the two lovers the delay caused by this side trip up the Persian Gulf had meant merely another week of paradise, but now the bishop had ended it all by proposing his absurd chess game.

Constance watched the movements of the little carved ivory horses and bishops and foot-soldiers with vast interest. She did not understand the moves, but those sinister-looking warriors were fighting out her destiny. A dark red knight on horseback tore through Fenworth's line of pawns and demolished two white foot-soldiers and a saintly-looking white bishop with flowing beard before it was captured and removed from the board. The dark knight looked so evil and terrible and it moved about the board in such an erratic and apparently illogical way that Constance conceived a terror of it. She stared at the two pieces as they stood side by side on the table, after they were removed, the saintly white bishop with a smile on its face and the dark horseman glowering.

She turned from the discarded pieces to look again at the game as the other dark knight was laid low in exchange for one of Fenworth's white knights. Constance felt somehow happier, knowing that the two evil-looking horsemen were removed from the board. Anxiously she studied Fenworth's face. He seemed worried. In truth, the game was going not at all to his liking. Bishop Fergus had forced a terrific attack upon his queen, which could not be rescued without the absolute sacrifice of a piece.

Fenworth sank dispiritedly lower and lower in his chair, desperately pondering his next move. Suddenly his hand trembled and he shot at Constance a glance of hope. He sat up straight in his chair. His heart beat so loudly that he feared the bishop must hear it. He tried to maintain his calm, but only the bishop's preoccupation with the game prevented him from detecting the new hope and anxiety in Fenworth's face.

After carefully studying the board before him, Fenworth deliberately abandoned the white queen to capture and moved his remaining white knight into position for an attack upon his opponent's king. If Bishop Fergus should take Fenworth's queen instead of building up a defense for the king, then Fenworth would win the game within four moves.

Would the bishop see his danger? He considered his next move for what to Fenworth was an interminable time, poising his hand over the white queen as if about to capture it. Fenworth restrained his jubilation, and the bishop withdrew his hand and pondered again. Fenworth raised his eyes from the board and looked across the yellow sand of the desert, seeking even a stunted tree on which to rest his gaze. Only a cloud of dust, probably a mile away. He turned again to the board.

Would the bishop never move? His finely carved head was still bent over the game as he studied the positions of the pieces, holding the edge of his spectacles against his lips. He saw danger threatening him in Fenworth's move, but he did not see the inevitable checkmate that would defeat him if he captured his opponent's queen.

Both players were so intent on their game that they did not hear a smothered exclamation from Constance, who was looking out over the desert, watching the cloud of dust draw rapidly nearer. The bishop's fingers closed over the white queen and lifted the piece from the board.

"Checkmate!" Fenworth shouted jubilantly.

"Checkmate?" the bishop echoed incredulously.

"In four moves!" Fenworth explained joyously. "You should have perfected your defense. But now—"

HIS sentence remained unfinished, for Constance cried out

again, sharply. Fenworth sensed alarm in her tones, and he sprang

to her side, overturning the board and spilling the chessmen. The

girl's eyes were fixed upon the desert.

Fenworth glanced across the ribbon of shallow water that separated the grounded yacht from the shore. A troop of Arabian horsemen was spurring directly toward him. They were already within a few hundred yards of the water's edge, and riding full tilt for the yacht. The sand flew out in clouds behind them. The little stretch of desert that intervened narrowed rapidly and disappeared under a rush of flying feet and the splashing of horses' hoofs into the warm water of the Persian Gulf.

The troop rode across the shallow water of the sand bar, and in another moment were beside the yacht. They uttered not a sound, these silent men of the desert, but stood on the backs of their steeds and came up the side of the yacht hand over hand, leaving the horses champing in the water.

One of the Arabs seized Constance, who struggled and cried out. Fenworth, recovering from the amazement that had paralyzed him, lifted a camp-stool. Before he could swing it, another Arab deftly twisted his arm. The stool fell to the deck, and Fenworth was quickly thrown and trussed. The crew of the yacht was overpowered with ease. The skipper had not even the opportunity to seize his revolver. The Bedouins bound them each and every one, and passed them over the side of the yacht to the men below like sacks of flour.

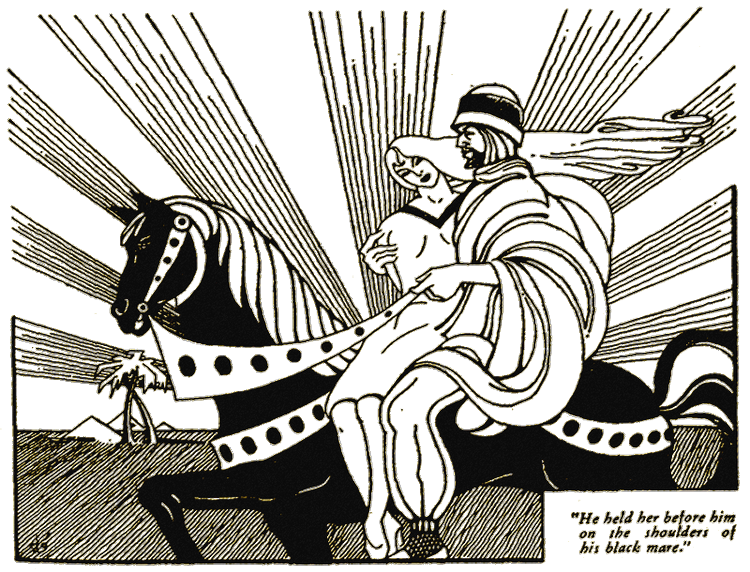

Speechlessly, as they had come, the Bedouins rode away across the desert with their captives. The sun poured down mercilessly, and the cruel thongs cut into the flesh. The bishop suffered perhaps worse than the others, but he had no thought of complaint for himself. He cried out several times to Constance, who was carried by a handsome young Arab with short, silky black beard and prominent forehead, and black eyes that shone brilliantly, like polished ebony. He held her before him on the shoulders of his black mare, and occasionally he lifted her in his strong arms and swung her around so that she could be more comfortable.

The bishop was carried by an old, cruel-looking Arab whose Beard was streaked with gray, and who was absolutely indifferent to the comfort of his captive. Fenworth swung precariously across the neck of a swift roan, in front of a tall, strong Bedouin whose mask-like face gave no hint of what thoughts might lie behind it. Before long he suffered acute pain from his uncomfortable and cramped position. The pitiless heat made him dizzy as they rode into the face of the westering sun.

As they faced more and more that blazing disk, Constance's captor pulled the hood of his burnoose down over his forehead to keep out the sun, and turned the girl more and more toward him to shield her from the glare. Thus the two found themselves gazing into each other's eyes. Frank admiration gleamed in the Bedouin's lustrous black eyes, and he held her very firmly and gently, as the girl duly observed in spite of her fright.

The ground became more uneven, and was cut up by wadis. The troop crossed the dry beds of several, and Fenworth involuntarily cried out at the rough jolting as the horses loped down and up again. But the Bedouin who held Constance lifted her tenderly in his arms as they went across the wadis, and protected her from the jolting.

AT length, as the sun was touching the rim of the desert, the

troop, at a sharp command from the Arab who held Constance,

turned north up a wadi, where the going was easier than across

the open desert. They followed the wadi for perhaps half an hour,

then turned westward again at another command and rode slowly up

a long hill. The barking of dogs and the cries of children were

borne to the ears of the prisoners. As they reached the summit,

Constance's captor turned her around so that she could look

down.

She gasped in astonishment. Spread out before her in the dusk was no temporary tent-village of nomads, but permanent buildings, waving palms, and a great pool of water. They had been brought to an oasis in the most inhospitable part of the Arabian desert, and a welcome sight it was to the travel-worn captives.

The Bedouins broke their silence for the first time that day, and began to talk excitedly among themselves. They carefully picked their way among a band of sheep, then broke into a gallop and charged down into the oasis.

A mob of dirty children and barking dogs immediately surrounded them, and several youths ran over to the arriving horsemen. A huge black slave, wearing the burnoose of the Arabs, stood motionless before the doorway of the most pretentious of the buildings, fixing his gaze with utmost interest upon the strangers.

To Constance, when her bonds were removed and she was placed upon her feet, they seemed to have arrived in some storied village out of the Arabian Nights. A large central building in Moorish style, made out of colored clays, slender beams and curiously cut stone, stood immediately in front of them. Radiating from this were galleries, like the cloister of a monastery. Behind them were the low mud dwellings of the Arabs, ornamented, like the central building, with colored clays and carved wood. A large pool, bordered with date palms, lay to their right, and to this pool the whinnying horses were allowed to stray.

The prisoners were led at once through the portal of the main building, past the stolid black slave, and conducted into a central court. There they were grouped around a fountain, which flowed slowly through the court. Its waters were carried away to the pool through a stone gutter.

The young man who had carried Constance left them standing by the fountain while he went through an arched doorway into an inner room. He returned almost immediately with a gray-bearded man, whose entrance the other Bedouins acknowledged by profound bows. He was clad in spotless white, and wore about his neck a sparkling necklace from which depended a large black pearl. The deference paid him by the others, the air of mastery with which he approached the prisoners, the whiteness of his garments, all marked him as one who possessed authority. His vivid black eyes looked out upon the world through deep wrinkles, and his expression was the incarnation of curiosity and eagerness. With cautious dread Constance studied his face, bronzed and chiseled by the winds of the desert. He might be either good or bad, for ail that she could read in his countenance. Certain it is that his face at the moment looked kindly rather than hostile.

The Arab approached the bishop. "English?" he asked.

"No. We are Americans," the bishop replied.

"But you know how to speak English?"

"Yes," said the bishop.

"That is good," the Arab answered, a million wrinkles carving his face as he smiled. "You are no longer prisoners, for you were also our allies. I was with Lawrence in the war against the Ottomans. I am the Sheik Ferhan ibn Hedeb, and you are my guests. Smeyr!" he called, raising his voice and clapping his hands thrice.

The black slave who had stood before the entrance came quickly in and prostrated himself before his master in a profound salaam. Sheik Ferhan gave a few crisp orders in Arabic, and Smeyr retreated backward through the door.

"Smeyr will have the women place dwellings in order for you," said the sheik. "He will be the slave of the lady during your visit. I have place for several of you in the palace, and the rest must stay in the dwellings."

Sheik Ferhan glanced around with the pride of possession.

"Now I would know the names of my eminent guests," he continued, "and chiefly the name of this lady, who is a dream of beauty."

He bowed low, and Constance flushed.

"This is my daughter Constance," the bishop said. "I am Bishop Fergus of San Francisco, and this is Fenworth, the young man who is one day to be the husband of my daughter."

Fenworth gave Constance a quick look, and the flush on her cheek became deeper. Sheik Ferhan's appraising glance covered Fenworth from the soles of his feet to the crown of his head.

"Smeyr!" he cried, as the black returned.

He gave further commands, and the slave extended his hands and stood expectantly to one side.

"Smeyr will lead your people to their dwellings, Bishop," the sheik explained. "You and your beautiful daughter will remain here, with your friend. In thirty minutes all will return and take lebben. You are very tired. You will rest here— three, five, seven days, perhaps. Then you will be taken back to your ship. I am most unhappy that my men caused trouble to you, but most happy that you are here. I will show you the hospitality of Bedouins, like nothing else in the world. Do you like lebben?"

"Lebben?" the bishop repeated. "I do not know the word."

"Our goat's milk, soured and fermented. Very good, very strong, very stimulating. But there will also be dates, and my women will prepare sweet goat's milk for the lady. I am told that your women always drink their milk unsoured."

Sheik Ferhan himself conducted the bishop, Constance and Fenworth to their rooms. Smeyr returned shortly, and carried to Constance a huge basin of water. He discreetly withdrew, and knocked on the post of her doorway when he thought a sufficient time had elapsed for her to prepare her toilet. She handed the basin back to him through the curtains that served as door, and the black then carried it to the bishop, and afterward to Fenworth, without changing the water.

A few minutes later Sheik Ferhan called to his guests, and they came out into the court, where they were joined shortly by the remaining members of the bishop's party. Seating Constance on his right and her father on his left, the sheik sat cross-legged on the floor. A bowl of soured milk was placed before each of the guests, and the sheik's women passed around salvers piled high with golden dates. Constance drank a long draft of goat's milk. Sheik Ferhan did not partake, aside from taking a few dates, explaining that he had eaten his daily meal some hours before.

"But in my country we eat three times a day!" Constance exclaimed.

"Three times!" Sheik Ferhan echoed. "Then why do you not become fat and ugly, like the Ottoman women? But no, you are thin and graceful, like a fox. I think you eat very little at each sitting."

He looked well pleased with himself for his compliments. Constance dimpled, and Fenworth looked grave.

AFTER the meal, Sheik Ferhan clapped his hands four times, and

the Arabs who had captured the bishop's party came into the

court. They bowed low, and then came over to the sheik, bowing

once again. The tall, handsome Bedouin who had carried Constance

was introduced to her as Zadd. He bowed low before her, and

touched her hand with his fingers, pronouncing the name

"Constance" very carefully. He was presented to each of the

party, and then, bowing low again before the sheik, he and his

companions departed.

"Zadd wants the lady to know his great sorrow at your discomfort," Sheik Ferhan explained. "We arc all sorry to annoy you, but happy, very, very happy, to have you with us. Every house is open to you. Ask for what you wish, and it shall be yours. If you have coins about you, my people will be glad to have some. But you must offer them when you enter their houses. Then they are gifts. No Bedouin will take pay for hospitality, but they like coins as gifts. They are very proud, my Bedouins. Two centuries on the oasis have not made fellahs of us. But now you are very tired. You will want sleep. Tomorrow will be time to see my people and my good oasis. Peace to you!"

Bowing deeply, he withdrew. Smeyr conducted the crew of the yacht to their dwellings, and the bishop, Constance and Fenworth went to their rooms.

CONSTANCE lay wide-eyed on the woolen mattress in her room,

thinking over the exciting events of the day. She had never met

anyone quite so courtly as the old sheik, who had rescued her and

her party from the hands of his tribesmen. She thought of the

tales of Harun-al-Rashid, and drifted insensibly into slumber.

Sheik Ferhan, Harun-al-Rashid and the handsome Zadd were

inextricably mixed in her dreams.

Bishop Fergus, his mind relieved by the benevolent protection of the sheik, soon dropped to sleep, despite the soreness of his body after the long ride across the desert.

Fenworth, alone of all the party from the yacht, did not sleep. He had seen the look of admiration on Zadd's patrician face while crossing the sands, and although he was too much preoccupied with his own discomfort and danger to think much about it then, it troubled him now. But what the attitude of Sheik Ferhan might be troubled Fenworth even more. The young American had watched the sheik closely during the meal, and in his face he read shrewdness and crafty cunning. To Fenworth it was obvious that Sheik Ferhan desired Constance. A look of annoyance had darkly wrinkled the sheik's face when the bishop told him that Fenworth was to marry Constance. The look disappeared almost as soon as it was born, but Fenworth had seen it, and it made him tremble.

Another man slept but little that night, had Fenworth but known it. That man was Zadd, for he, too, had looked upon Constance, and he, too, had seen the look of desire in the eyes of Sheik Ferhan. The sheik had promised protection to the party, and henceforth the Americans were no longer prisoners, but guests, and every member of the tribe was bound by the laws of Bedouin hospitality to treat them as friends. But for some reason that he could not explain, some imperceptible insincerity in Sheik Ferhan's manner, or perhaps only an impalpable and meaningless shadow of fear, Zadd was troubled.

Constance awoke early, and was about to arise when one of the sheik's women came into the room, bearing a basin of water and a coarse linen towel. Her ablutions finished, Constance entered the court. Fenworth was there before her, pacing stiffly back and forth, keeping watch on her door. As the curtain was pushed aside he came forward eagerly and greeted her with a betrothal kiss, the first he had been able to give her since he won her at chess the day before. The bishop joined them a few minutes later, walking slowly, sore and weary from his ride across the desert. "Happy morning!"

The three turned quickly as Sheik Ferhan entered the court. He was smiling broadly. Three women accompanied him, bearing milk, butter and dates for the breakfast. The sheik again declined food, but sat and talked with his guests while they ate.

"I am a Bedouin," he said. "One meal a day is enough. If I ate more I might become fat, and that would be ugly. I have great wish to show our oasis to you, and we shall have horses racing. And you must meet my wife. I have but one, although the great Prophet (on whom be peace!) allows four to every man who, like myself, can give the necessaries of life to so many."

He smiled his broad smile, his little black eyes twinkling and little wrinkles radiating good-humoredly from the corners.

"Come, my friends," he said, smiling again, and stroking his grizzled beard, "I will show to you the hareem."

He offered Constance his arm, with all the courtly grace of a Solomon greeting Sheba's queen. Constance laughed delightedly and went with him through the curtains into the secret recesses of the dwelling. Her father followed with Fenworth. A tall woman, arrayed in spotless white, without a veil, waited in the hareem, attended by two women slaves. She evidently expected the visit.

"My one and only wife, Adooba," said Sheik Ferhan, saluting her with a deferential bow.

He added a few words in Arabic. Adooba smiled, and bowed to the three guests in tum. She looked keenly at Constance. Fenworth, watching her narrowly, saw distrust written on that desert-bronzed countenance.

Conversation was impossible; so, after an interchange of formalities through the sheik, they passed the baths of the hareem and went out into the open air, the sheik and Constance leading. Zadd and one other, who served as interpreter, awaited them, and the black Smeyr followed a few paces in the rear. Smeyr never left the party throughout the day.

Zadd's companion, in very bad English, introduced himself to Fenworth and the bishop as Faris, who served with General Townshend's army in the advance on Bagdad. While Sheik Ferhan explained everything to Constance, Fans tried to do the same for the bishop and Fen worth.

"I learned English very good," he explained. "I interpreter at English army. I interpret you oasis. Here big water pool—water tree, goat, sheep, horse, men. Here horse run for you this today. Ten, and ten more, with Zadd on black she-horse. You see, after dinner."

THE party completed its tour by visiting the mud houses. The

crew of the yacht had already struck up an acquaintance with the

Arabs the evening before, through the medium of Fans, who had

suggested that they would like gold coins as keepsakes, and was

desolated to find that the Americans had no coins in their

pockets when they were dragged from the yacht.

All of the Americans—Constance, Fenworth, the bishop, and the fourteen men of the crew gathered in the sheik's courtyard for the noon meal. Zadd and Faris formed part of the party, and Adooba, who usually ate in the hareem, sat silently beside her lord as a special honor to the strangers. The sheik's women brought heaping trays of dates and bowls of milk, and a huge wooden platter containing the great fat tail of a sheep, surrounded by splintered masses of cooked mutton. Bones and meat were mangled together and boiled without seasoning. Lumps of butter and dough were ranged around the edge of the platter, and bits of liver surrounded the tail of the sheep.

The meal was far from appetizing, and there were no plates from which to eat it. The platter was first placed in front of Sheik Ferhan, who handed it on to Constance and instructed her how to eat from it. He passed a little dish of salt to her, and she dipped her fingers into the meat, salted it and tasted it. She did not like it, and turned her attention to the milk and dates, while the sheik passed the platter to Adooba. Then he ate from the platter himself, and it was passed in turn to the bishop, Fen worth, and the members of the crew. There was much of the strange food left when it reached Zadd and Faris, and the sheep's tail had not been touched, but they fell upon it like hungry wolves, and passed the scraps to Smeyr.

Bowls of water from the fountain were then passed among the guests, and the party arose and proceeded to the smooth plain at the west of the pool, where the races were to be run.

Twenty young Arabs rode in the first race, which Zadd easily won on a speedy little black mare. Then came spear-throwing, foot-racing between the youths of the oasis, and pitching of quoits. Sheik Ferhan explained the sports to Constance, and Fenworth chafed at the attentions he paid her, for the newly engaged young man had hardly had a word with his sweetheart all day. He found his opportunity to join her after the races, when the sheik dropped back to chat with the bishop.

"It's about time," Fenworth commented ill-naturedly, as he took the sheik's place at Constance's side. "I thought that old mage was going to stick to you forever. He must bore you frightfully."

"On the contrary," Constance said, "I think he's clever. He is certainly terribly interesting. I believe I like him immensely."

"You're as bad as the White Queen in Through the Looking-Glass, who believed six impossible things before breakfast," Fenworth growled.

"Surely you aren't jealous of a nice old Arab sheik," Constance replied.

"Why," Sheik Ferhan was asking the bishop at the same moment, "why is your daughter going to marry that young man?"

"He is really very worthy," the bishop answered. "And besides, he won my daughter in a chess game. They are to be married on our return to San Francisco."

"What a pity!" Sheik Ferhan replied, shaking his head and stroking his grizzled beard. "What a pity!" he repeated, with a look of great shrewdness in his eyes. "So he won your daughter in a chess game."

For a minute he was deep in thought. A merry laugh from Constance broke up his revery, and he raised his head almost fiercely.

"Fenworth!" he spoke out sharply, in a tone of command.

Fenworth looked up. Sheik Ferhan rose and came toward him. His eyes were twinkling, and the little wrinkles at their corners writhed in mirthful exultation.

"You arc a player of chess," he said, with a suggestion of contempt in his voice. "Tomorrow you will display your ability. You will play with me a game, and the chessmen will be Irving men and women, and the pieces will walk across a giant checkerboard marked out on the plain. You and I will direct diem from a platform built like a tower at one end of the field. The beautiful Constance will be the white queen, and Adooba will be the dark queen. It is fitting so, for Adooba's face has been darkened by the sun, but the face of the American girl is white like milk. You have seventeen persons in your party from the ship. You will play, and the other sixteen will be pieces in our game. The castles will ride on camels, and the knights will ride on mares, that we may know them as we overlook the checkerboard from our tower. The bishops will be robed in long white burnooses, and the pawns will walk on foot. Thus will there be a game that will amuse us for half a day."

"But not for a stake," Fenworth interposed. "I won Constance once in a game, and I don't want to stake ray fortune again in that way."

Sheik Ferhan's face became terrible, but the cloud passed on the instant and his face wrinkled again in a smile.

"If I wished to have that beautiful girl in my hareem," he said, "I would ask her, and not come to you. A woman loves, or she does not love, and the hazard of a game can not change it. Smeyr!"

He brought his palms together sharply, and Smeyr was before him almost immediately. The sheik gave him orders in Arabic, and he withdrew at once.

"Over there will be the platform," said Sheik Ferhan. "Here will be the field. We will mark the dark squares by rugs and cloths, and the sandy ground will be the white squares. But you would now eat dates and milk. I find the Americans do not like lebben. But dates and milk there are for all. We will now withdraw to the palace that the Americans may eat."

The repast over, Sheik Ferhan suggested to Constance that they go out by the pool and watch the moon.

"They tell me," he said, "that at Mecca the moon looks just the same as it docs here. Do you see the moon in San Francisco?"

As they came into the open and saw the moon silvering the desert, Constance tugged at Sheik Ferhan's sleeve.

"Oh, beautiful!" she exclaimed. "I have seen the moon just as it is now, as I looked across the water from the ocean beach, by the Cliff House in San Francisco, and I have watched it sink lower and lower until it was drowned by the swell of the Pacific Ocean."

"Then the moon must shine everywhere," Sheik Ferhan said, measuring his words. "I do not understand. It is here, and it is there at the same time. Mecca lies across the desert, hundreds of miles south, almost within sight of the other sea, on the other side of the land. And Aleppo is far away, north of the sunset, in the Ottoman country, yet the same moon shines there. And London and San Francisco are at the ends of the world, farther even than Aleppo, and they all have the same moon. My poor brain can not understand it."

Constance laughed. Her mirth seemed to please the sheik, for the crow's-feet around his eyes wrinkled even more than usual, and he beamed ecstatically.

"But you will teach me many things, about the moon, and the ocean, and your country, and I will learn from you each day, oh palm-like stranger from across the water."

Constance looked at him wide-eyed.

"But I am to return!" she exclaimed. "You don't mean—you can't mean you will hold me here!"

"Your beauty is like the palms waving in the moonlight, after a weary ride across the sands," said Sheik Ferhan. "It tells of sweet repose and whispers of cooling waters and fragrant flowers. I am like a wanderer in the desert. I have been lost in the sands, and you arc the oasis that tells me I have found my rest. You are not fat and ugly like the Ottoman women, nor dark like my own race. Listen, daughter of strangers. My wife Adooba is very sweet, but you are far sweeter than she. The great Prophet had four wives, which Allah allowed to him. I have but one. You will rule my harcem, and the black slave-girls will serve you, and you will be my second and favorite wife."

Constance kept her eyes fixed on Sheik Ferhan during this speech. He hung his head, as abashed as a schoolboy declaring his love. His crafty glance sought Constance's face and shifted again to the ground.

"The great game of chess on the plain tomorrow will celebrate our wedding," he added, thoughtfully.

Then his arm encircled her and drew her to him, and his eyes sought her face. Constance struggled and pushed him away. He released her and gazed fiercely into her terrified eyes, reading there her horror and fright.

"You prefer the weak young man from San Francisco?"

Constance nodded.

The sheik's tone became hard.

"Very well, then. The Sheik Ferhan is refused. The weak young man from across the water is winner. Then let him earn his prize. Let him look well to his game, as we move our human chessmen across the checkerboard tomorrow."

He meditated a minute. His face became tender.

"Let us go inside," he said. "Your weak young man with the white face will be impatient."

He bowed low and motioned to her to precede him.

An excited whispering caused her to turn her head. Two white figures were moving by the date trees at the pool's edge. She wondered if they had overheard Sheik Ferhan's declaration. The sheik saw them, too, but made no sign. The moon shone upon their faces, and Constance thought she recognized them as they withdrew into the inky shadow of the palms. One was Fatis, the interpreter. The other was Zadd.

THE shouting of children, the barking of dogs, the chanting of

a Bedouin and the hum of voices woke Constance at daybreak. She

arose and dressed, and found Fen worth and her father already

pacing the court. She ran to her father and threw her arms about

his neck. Fenworth stood by, vaguely troubled, and as Constance

told of Sheik Ferhan's proposal the young man clenched his fists

in impotent anger.

Two Arab women entered the court with trays of dates and figs, and pitchers of goat's milk. A minute later Sheik Ferhan joined the party and bade them good morning. He seated himself, smiling craftily, but did not partake of the food, as it was far from mealtime for him.

"The workmen are preparing the field," he said. "It will be ready very soon, and we shall have rare sport. With you directing, there will be just enough persons in your party to be pieces and pawns on your side. The fair Constance and the dark Adooba will be our queens. We will have a pretty game, very good to look at."

He clapped his hands, and Zadd and Faris came to his side. Shortly thereafter Adooba joined the group, and they proceeded toward the field, Sheik Ferhan walking with his wife, while Constance walked between her father and Fenworth. Zadd and Faris brought up the rear.

Constance clapped her hands in pleasurable excitement at the sight that greeted her. A huge checkerboard was mapped out on the plain. Rugs formed the dark squares, and gleaming sand the white squares. At the outer edge, toward the desert, and between the opposing groups, was built a platform ten feet high, from which Sheik Ferhan and Fenworth were to direct their human chessmen. Opposite, in the blacker sand of the oasis, the sheik's workmen had sunk a hollow pit, which was filled with water. Beside this stood Smeyr, clad only in a snowy white girdle, his giant black limbs and body shining in the sun. At a signal from Sheik Ferhan he lifted high a huge bowl.

"This is the water clock, by which our moves will be timed," Sheik Ferhan explained.

He spoke to Smeyr, and the black cast the bowl down upon the pool. It began to fill with water, which forced its way through a hole in the bottom. The bowl settled lower and lower.

"It takes ten minutes for the water to fill the bowl so that it will sink," Sheik Ferhan explained. "As soon as you have made your first move, Fenworth, Smeyr will let the bowl fall upon the water and I will have ten minutes to make my move. If I have not moved before the bowl sinks, Smeyr will strike this brazen gong to show me that my time is used up and I must make my move at once. Whenever a piece is ordered moved, then Smeyr will empty the bowl and let it fall again upon the water, and the other player will have ten minutes to think out his next move, if he wishes to take that long. But let us begin."

He gave a few sharp commands to Zadd and Faris, and soon the human pieces were in motion toward the checkerboard. Camels stood at the board's four corners, awaiting their riders. Next these, on the north and south edges of the mammoth board, were hobbled mares for the knights to ride—white mares for Fenworth's side, black mares for Sheik Ferhan. Bishop Fergus and the skipper of the yacht, in long white burnooses, took their positions on the squares next to the mares, to be the white bishops in this strange tourney. On Sheik Ferhan's side two patriarchal Bedouins with gray beards were the bishops.

The sheik himself escorted Adooba to the queen's square, and Constance, mistaking her place, walked to the white king's square, from which Fenworth laughingly shifted her to the queen's square adjoining. The pompous cook from the yacht, with an improvised crown on his head, stepped to the king's place. In front of each of the opposing lines of pieces, after much laughter and confusion, were at length ranged the pawns—the eight remaining members of the yacht's crew on Fenworth's side, and eight young Arabs on Sheik Ferhan's side.

Then the sheik and Fenworth, accompanied by Zadd and Fans, made their way to the platform. A small checkerboard was placed between the two players on a little table, with ivory and ebony chessmen, that they might direct the human pieces by their mimic counterparts. Zadd and Faris stood on the platform with folded arms as Sheik Ferhan and Fenworth took their seats.

Then Sheik Ferhan spoke. His voice was calm and even, and bore no trace of the passion that guided his words. Fenworth, watching him intently, read his feelings only in the narrowing of his eyes. Zadd, uncomprehending, stood impassive, but Faris, the interpreter, started, and on his face were dismay and consternation.

"Young man with the weak face," said Sheik Ferhan, softly, "last night I offered the American girl the honor of ruling my hareem as my second and favorite wife. She refused. You, and she, and all of you, are my guests, by my own act, although my men hoped to hold you for ransom, when they captured you. I could have kept you as prisoners, but I did not. But the American girl has hurt me—here!"

With a theatrical gesture, he struck his clenched fist upon his heart.

"However," he continued, quickly recovering his tranquillity, "I shall not force her into my hareem. But I can not forget the hurt. I am a Bedouin, and therefore proud. Young man with the weak face, if you love this girl you must fight for her. You must prove your right to her in this chess game. Listen well to me, and hear my offer.

"If you lose, then you, and she, and all of you, will be sent into slavery among the lost oases. Your Europeans' maps do not show them, and your travelers have never visited them. Your consuls and your soldiers can never find you. You will disappear, and be heard of no more. And you will be separated from the American girl. She ha$ refused the honor of becoming my wife. I accept this fate, but she will grace the hareem of some sheik in the lost oases.

"But if you win, then you, and those of your people who are not captured in our friendly game of chess, will be sent back to your ship, with all the gifts my little wealth can provide. If you still keep your white queen uncaptured, then you can take her with you. But if she, or her father, or any other of your people are removed from this great checkerboard, then they will be sent as slaves to the lost oases, and the rest of you will return to your ship. Do you understand?"

Fenworth set his lips tightly together. An unwonted pallor blenched his cheeks. He looked steadily into Sheik Ferhan's eyes, and the old man's gaze fell before the American's stare.

"Come, young man with the weak face," said Sheik Ferhan, "I will be fair. I tell you that the American girl will be sold into a hareem if you lose her in this game, but I offer you Adooba if you remove her from the checkerboard in our game of chess. What is fair to me is fair to you. Win the game and capture the dark queen, then you may take Adooba away to your ship. And if I capture the white queen, then you lose the American girl. I warn you that I am an excellent player. Many nights I played with the English officers and beat them badly. Let us begin."

Zadd raised his hand at the sheik's command, and Smeyr struck the gong. A brazen note rolled over the plain. The chess game had begun.

FENWORTH carefully advanced the pawn in front of the dignified

cook from the yacht, who stood in haughty majesty, with his mimic

crown, for all the world like a real king standing before his

throne. The gong sounded again, and Sheik Ferhan ordered his own

king's pawn into the center of the board. Zadd shouted his orders

in Arabic, and the black, who had cast down the water clock upon

the pool, picked up the bowl and emptied it. Sheik Ferhan's move

was duplicated on the field, and Smeyr cast the empty bowl upon

the pool.

That part of the Arab population not engaged in the game crowded around the mammoth checkerboard and watched in fascinated but uncomprehending interest the progress of the play. Women and children elbowed and jostled one another as Zadd and Faris ran among the living figures of the game directing their movements according to the moves made by Fenworth and Sheik Ferhan with the carved ivory and ebony pieces on the platform.

Again and again Smeyr struck the brazen gong, emptied the bowl, and cast it down again upon the pool. Cautiously the two players maneuvered their black and white pieces, and Zadd and Faris duplicated the movements on the field, sometimes shouting out the directions, and sometimes leaving the platform and going out among the human pieces. The women laughed as the hobbled mares lumbered over the squares, bearing the knights on their backs, and the children clapped their hands in gleeful excitement. But Fenworth sat silently, with mouth tightly compressed and eyes glued to the board in front of him, only raising his glance from time to time to make certain that Faris had properly repeated his move among the human chessmen on the plain. He castled, and a camel lumbered to its feet under Faris's blows. The children shouted as the ungainly beast, rocking from side to side, moved to the spot just vacated by Bishop Fergus, who had been shifted to the center of the board.

Then Sheik Ferhan moved out Adooba, using her to launch an attack against Fenworth's queen. Fenworth gazed fixedly at the position in front of him, as if to verify the danger in which the white queen stood, then shot a quick glance toward Constance. She blew a kiss to him and smiled radiantly, ignorant of the danger that enveloped her. Fenworth fixed his attention again upon the board, and blocked the sheik's move. Faris descended from the platform and duplicated the move upon the plain.

Sheik Ferhan darted one fierce glance at Fenworth, and set himself to the task of capturing the white queen and removing Constance from the field. He forced an exchange of knights, and the children shouted again as the hobbles were removed from the mares' legs and the riders dismounted.

The benignant smile faded from Bishop Fergus' face and he muttered an angry exclamation, for two Arabs from the sheik's household set upon the sailor who had been riding the mare as Fenworth's queen's knight, and bound him and laid him down upon the plain a prisoner. A murmur ran through the crew of the yacht, and the faces of the rest of the concourse expressed genuine surprise. Zadd stood for a moment stock-still, as if unable to trust his eyes.

He expostulated with the two Arabs, but their explanation seemed to satisfy him, and he strode bade to the platform. Smeyr struck the gong again and cast down the bowl upon the pool, and the play was resumed.

Now the two antagonists settled down to a terrific duel. Fenworth used the full ten minutes allotted to him for each play, but Sheik Ferhan made his decisions rapidly, moving the ebony pieces on the board almost as soon as Fenworth's moves were completed, and sending Zadd post-haste to carry out the maneuver on the field. Two of Fenworth's pawns were exchanged and set bound beside the sailor, and Zadd, still uncomprehending, remonstrated with the sheik. But Ferhan spoke sharply to him, and he descended from the platform to carry out the instructions of his chief.

THE game was turning slowly in the sheik's favor, and

Fenworth, trying desperately to save Constance, found himself

open to a strong attack upon his king, an attack that seemed

certain to win the game for Sheik Ferhan. But the Arab's reckless

attack upon Constance had overreached itself. It exposed the

sheik to the loss of a piece, and with it the game, for the

players were too evenly matched for Sheik Ferhan to expect

victory if Fenworth had the absolute advantage of a piece. To

force the exchange and gain the piece, however, Fenworth would

have to give up Constance in exchange for the Arab's queen.

Bishop Fergus saw the desperate plight of Fenworth's game, and realized Sheik Ferhan's treachery. The attack upon the white queen made him fear that the sheik planned to take Constance into his hareem if he captured her in the play. He saw Constance's danger and knew that he was the buffer that must be interposed and exchanged to prevent an interchange of queens. He thrust two fingers into his mouth and whistled shrilly to attract Fenworth's attention.

Fenworth was conscious of a vast irritation. This was his game, not the bishop's. In that moment he hated the bishop for distracting his attention from the pieces before him. Had he not proved himself the better player by winning Constance from him? Why, then, did the bishop not keep out of it?

If he protected Constance by interposing her father, then only the flimsiest chance of winning remained to him, for the position against him was very strong. Slavery threatened all of them, and Sheik Ferhan had said that he and Constance would be sold to tribes quite far apart. He looked out over the field and saw that the water clock was slowly sinking. The minutes were creeping on, and beads of sweat stood out on Fenworth's forehead as he fought to decide his move within the time allotted to him.

If he should accept the exchange and surrender Constance to a temporary slavery, would not a rescue be possible? Most of the party would return to the yacht, and the American government would surely punish the sheik and find those whom lie had sold into the lost oases. Had it not rescued an American citizen from the Moroccan bandit Raisuli? The skipper of the yacht was an Englishman, and the British government possessed great influence with the Bedouin tribes, because it had actively aided the Arabs in their struggle for independence. The British government could surely force the return of the prisoners. But if he protected Constance now and lost the game thereby, then all of them would be enslaved and no news of their fate would ever reach the outside world.

The cries of the Arab children had ceased. Everyone sensed some important decision to be made, and the throng hung upon the event with breathless interest, even though the spectators did not understand the maneuvers.

Hardly more than the rim of the bowl still showed above the surface of the pool. Fenworth scowled in silent rage. If the water clock would only give him more time to make up his mind! How could he think with that sinking bowl speeding away the seconds, and Bishop Fergus shouting at him?

He stared sullenly, unable to withdraw his eyes. The last few seconds seemed hours. What had that bowl to do with him, anyway? He experienced a strange anger at it.

And now the bowl swirled, and sank from sight. The huge black lifted his shining arm and struck a blow on the brazen gong. It seemed a full minute before the club in Smeyr's hand touched the gong and the harsh sound boomed discordantly through the air, but it was in reality only a small pan of a second.

FENWORTH'S world seemed to fall away from him. He moved the

ivory bishop to protect his queen, and Faris hastened to the

field to duplicate the maneuver. He had made his decision and

taken the fighting chance.

Sheik Ferhan without hesitation lifted the ivory bishop from the board, and sent Zadd to direct the removal of Bishop Fergus to the group of prisoners who sat, with arms bound behind them, near the water clock.

Now Faris, returning from directing Fenworth's move, encountered Zadd; He told him what Zadd already half suspected, and it made the tall Arab's handsome face become for the moment distorted with strong anger. Sheik Ferhan, from his place on the platform, called to him to hasten. Zadd gave Bishop Fergus over to the two Arabs from the sheik's household, and they tied his hands behind him. Smeyr cast down the bowl, and the game was on again.

Fenworth gnawed his thumbnail and tried to see daylight through the gloom that enveloped him. On the board before him, as on the field beneath him, with carved or with human pieces, he saw defeat and slavery. The net drew tighter, and Fenworth struggled vainly, as the water clock again told off the seconds against him.

Zadd and Faris returned to the platform, and the handsome Bedouin spoke to Sheik Ferhan in low, measured tones. Fenworth, who knew no Arabic, nevertheless felt the restrained feeling that surged beneath Zadd's words. He saw the determined visage of the tall Arab, and the clenching and unclenching of his left hand as he spoke, and he saw the eyes of Sheik Ferhan narrow to mere slits.

Slowly the ancient sheik rose to his feet. As slowly as he had risen, he extended his right hand and grasped the hem of Zadd's burnoose. Speech poured from him in a flood, beginning low at first and swelling in angry volume as his voice rose higher and higher. Zadd closed the fingers of his powerful left hand around Sheik Ferhan's knuckles and wrenched his grasp from the burnoose. Then he deliberately pushed his chief to one side.

Raising his voice until it carried clearly across the giant checkerboard and rang out over the pool of the oasis, Zadd addressed the Arabs. He had uttered but a few words before Sheik Ferhan smote him upon the neck and tried to pull him from his perch.

Meantime Faris broke his silence and tried to explain to Fenworth what was happening.

"Zadd say Sheik Ferhan break Bedouin law. You no prisoner, you friend. Sheik must be friend to guest. Zadd say sheik break hospitality, make all you prisoner. He say Sheik Ferhan no more sheik."

Zadd broke the sheik's hold and sent the old man spinning into the board, knocking the pieces over. Sheik Ferhan crashed through the little table and fell from the platform to the ground, ten feet below, for there was no railing to break his momentum. He struck his head sharply against a corner post of the platform, and lay still on the ground.

The knights and castles and bishops and pawns came running swiftly across die sand to the base of the tower. Faris leapt the ten feet to the ground, and was first to reach his fallen chief. Zadd stood with folded arms, while Fenworth sat in his place amazed at the sudden passage of events.

SHEIK FERHAN was dead. His neck had been broken as he fell

head foremost from the platform. And now Zadd addressed the

Arabs, vehemently at first, then more slowly and with more

measured accents. What he said was gathered, bit by bit, from the

hotchpotch of English that came from the willing but ineffectual

lips of Faris.

"Your sheik has shamed you," said Zadd. "He made these strangers his guests, and by immemorial custom their persons were inviolate thereafter. He abused the sacred privilege of host and made prisoners of his guests. He proposed to sell them to the lost oases. He broke the law of hospitality, which is the worst crime a Bedouin can commit. Thereby he forfeited his right to the title of sheik. And now he lies dead. Peace be with him."

Silence greeted Zadd's solemn words, broken only by a stifled sob from Adooba. The dark queen of the oasis sincerely mourned her fallen lord. But on Zadd's heart also there lay a shadow, for his face was eloquent of gloom.

He conferred at once with the other leaders of the little tribe, and it was decided to send the Americans immediately to their yacht, in the half-day that remained before sunset. Zadd rode beside Constance, in silence, for how could these two converse, since neither knew the other's tongue? He threw over her shoulders a snowy white burnoose to pro-tea her neck from the rain of heat rays, and he set a leisurely pace on his coal-black mare, so as not to weary the American girl.

He seldom looked at her, but Constance stole frequent glances into his finely formed face, with its strong nose and chin and short black beard. Fenworth rode immediately behind her, with an Arab escort, and the bishop rode third, beside Faris. Two by two, the party moved slowly across the desert.

The sun had set and the moon cast deep black shadows upon the yellow sand before they came within sight of old Granby's yacht. Still Zadd maintained the immobility of his countenance, and Constance gazed more and more often into his face. On the deck of the yacht several faces were seen, and a boat, with steam up, lay alongside. It was the relief boat from Muscat.

The Bedouins dismounted at a sign from Zadd, and Fenworth helped Constance to the ground. Faris again endeavored to convey his apologies for Sheik Ferhan's breach of hospitality. Then Zadd crisply ordered his followers to horse, and they rode away, each leading one of the horses that had brought the Americans back to the yacht.

Zadd was left with Constance. Diffidently he extended his hand in fare' well greeting. She grasped it, and smiled into his face.

"Constance," he said, tenderly, and repeated the name carefully, several times: "Constance, Constance, Constance," as if to engrave it into his memory.

Her face betrayed the sadness of her heart as she scanned his features. He kept her hand in his and gazed fixedly into her eyes as the moon shone upon her upturned face. Then the girl kissed him on the mouth, in view of Fenworth and her father and the crew.

"Good-bye, Zadd, my sheik," she said, and her lips trembled.

Ashamed to let him see the moisture in her eyes, she turned away and strode to the water's edge, where she awaited passage to the yacht.

Zadd mounted the snow-white stallion that had brought her from the oasis. Leading his own coal-black mare, he loped back into the desert. Constance, looking from the deck of the yacht a few minutes later, saw silhouetted against the horizon two horses, and on one of them was a rider. They lingered for a little, and she tried to call to him.

"Good-bye, Zadd," she cried. "Goodbye!"

The silhouettes disappeared beyond the ridge, and Constance laid her head on Fenworth's shoulder and wept.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.