RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

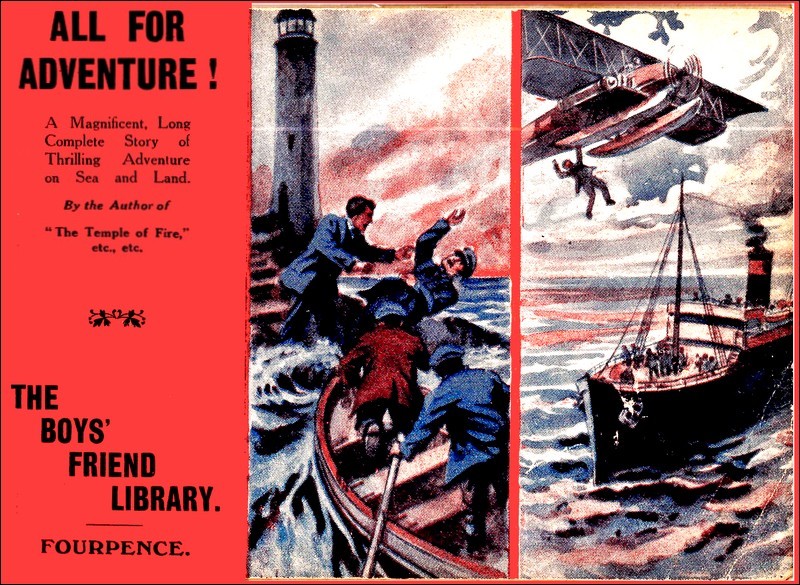

"All for Adventure," Boys' Friend Library, March 1918.

"BY Jove! This is grand! A letter from Ray Sinclair, asking me to join him in a trip to South America. Just the kind of thing I've been wishing and longing for ever since I was a kid. Splendid! Here's my chance at last!"

The speaker was young Lord Temperley, and the scene was the morning-room at Temperley Hall. He was seated at breakfast with Mr. Duncan, who acted in the double capacity of guardian and manager of the young man's estates.

For Lord Harry Temperley was not yet quite twenty-one; though no one would have thought so to judge by appearances alone.

Well built, muscular, almost a giant in stature, known at school and at his university as a splendid all-round athlete, he looked fully two or three years older than be really was.

In other respects he was equally well favoured by nature, being gifted not only with good looks, but with a sunny, good- humoured, genial disposition. Certainly he had very high spirits, which had caused his guardian at times to regard him as rather "a handful," but that only arose from an excess of energy. There was no vice in breezy, light-hearted, good-tempered Harry Temperley.

That something had happened now to rouse all his enthusiasm was evident as he sat there looking at the letter he held in his hand, his face aglow, his eyes dancing with excitement.

Mr. Duncan regarded him soberly. He was the exact opposite of his ward, being elderly, precise, and staid. But the look in his eyes was less stern than his bearing.

"What are you so excited about, Harry?" he asked quietly. "Surely you are not thinking of starting off to South America at a moment's notice just because someone you know is going?"

"As to that, Mr. Duncan, Ray Sinclair's uncle and my father were very great friends, as you know, and they once travelled together in the very part of the world Ray is now going to. And he says his uncle wished him to get me to go with him—and you know that my dear old dad always wanted to take me abroad with him, only at first I was too young, and afterwards he became an invalid."

The late Lord Temperley, Harry's father, had been dead nearly two years; while Ray Sinclair's uncle, Sir Ralph Sinclair, had died a few months before.

Thus Ray and Harry, who had been school-fellows together, had both been left alone in the world while still quite young men. For Sir Raymond Sinclair—to give him his full name and title—was only a year or so older than his chum.

"I hope you are not going to raise all sorts of disagreeable objections, Mr. Duncan?" said Harry, looking at his guardian with the quizzical, open-eyed, innocent air that the old gentleman often found so hard to resist.

"Hum! Hum! What's he going out there for?" Mr. Duncan asked, judicially. "Better read out to me what he says."

A slight shadow fell upon the face of the young enthusiast, and his brow became puckered with a puzzled frown, the reason being that his friend Ray was either a very bad writer or had written in a very great hurry, and with unusual carelessness. Anyway, his letter was not an easy one to decipher.

"All right, sir," said Harry. "I will read you what he says—that is," he added, hopefully, "as fast as I can make it out. For Ray has sent me the most awful scrawl that I—. However, here goes:

"'Dear Jumper,' he says—that's me, you know, Mr. Duncan. They always called me Jumper at school, because—"

"Because you were always like a cat on hot bricks, I expect," murmured Mr. Duncan. "But go on."

"'Dear Jumper,'" Harry repeated slowly. "Faith, it's not so easy to 'go on.' However, here goes once more—I'll begin again, so that you don't lose the thread. 'Dear Jumper,—At last I'm glued to—' Gracious! that's wrong, surely! Oh! he means 'glad.' 'I'm glad to say, I've got myself kettled.' I say, that can't be right! He can't have got himself kettled, you know!"

"Settled, perhaps," Mr. Duncan suggested.

"Why, yes—of course, it's 'settled.' He means he's got all his affairs settled up after his uncle's death."

"He was a very clever scientist—his uncle—wasn't he—as well as a great traveller?"

"Yes—a naturalist; and besides that, an inventor. He invented—or discovered—several very clever things."

"And the nephew, young Sir Raymond, takes after him in that respect, doesn't he?"

"Well, yes—or tries to. He's always trying to invent something new. However, to go on with this letter; he says his uncle left him a—'a sacred trust'—a mission. He is to go out to deliver something very important to the chief of an Indian tribe."

"Where?"

"In—er—British Guiana. Then he says when he has fulfilled his uncle's wishes, he will be free; and ready to travel with me anywhere—from Tottenham to Timbuctoo, or from the earth to Mars by special airship—if I like."

"Tut, tut! British Guiana, indeed!" said Mr. Duncan. "The idea of two young fellows like you going out there alone!"

Harry stared, evidently disappointed at this cold douche. "But—Mr. Duncan," he urged, "you know that my father wished me to go, and would have taken me himself if he had been well enough. I shall only be carrying out his wishes. And Ray says his uncle—Sir Ralph—particularly wished him to get me to go with him, because the Indians he is going to see knew my father. So, you see, sir, I can't very well refuse."

"H'm! Well, young man, it rests with yourself. In six months' time you will be twenty-one, and your own master, and you would go then, I expect, if I said 'no' now. So what can I say? Only this, my lad, that if you decide to go, I wish you good fortune and a safe return. And you can have an easy mind while you're away. I'll continue to manage everything at home for you, as I have done since your father's death."

Harry seized the old gentleman's hand, and thanked him warmly.

"Now I must go and rout out Barney," said he. "I must tell him he's got to come with me."

"Ah! Yes—that's a good idea," Mr. Duncan agreed. "Of course! He went over that ground, I remember, with your father. He'll help to take care of you."

Harry came upon Barney digging, bareheaded, in the garden of the little cottage which the late Lord Temperley had given him to live in.

He was a veteran hunter, and had, in his time, travelled almost all over the world. In particular, he had been the trusted servant and companion of Harry's father in his travels. He looked up as he saw his young master, and smiled a glad welcome.

"The top o' the mornin' to ye, me lord," said he.

"You rascal!" exclaimed the young man. "Call me 'me lord' again and I'll heave half a brick at you! How many more times am I to tell you of that?"

"Faith! Oi forgot. Misther Harry"

"That's better, me bhoy," Harry returned, blithely imitating the other's brogue. "It's Misther Harry ye always used to call me, an' it's Misther Harry ye'll go on sayin'—or I won't take ye with me where I'm goin'."

"An' where moight that be, me—Oi mane Misther Harry?"

Harry looked at him whimsically.

"D'ye know a place called British Guiana, Barney?" he asked.

Barney stared; then understanding came, and his face lighted up.

"Arrah, it's jokin' ye are, sorr" he said doubtfully. "Ye're niver thinkin' that—"

"But I am, Barney. And I'm more than thinking—I've made up my mind. And you're coming with me. So you can set to work packing. Clean up all our rifles and revolvers, and get out a list of the things we shall have to buy."

Barney shouted for joy, and would doubtless have thrown his cap in the air if he had been wearing one. As it was he pushed his spade into the ground with tremendous energy, dug up an immense clod, and flung it skywards with great gusto. It came back in a shower of small particles.

Then a thought struck him.

"Anybody else goin', sorr?" he queried.

"Only my chum, Ray—you know, Sir Raymond Sinclair."

Barney's face fell. He looked troubled. "Only him!" he muttered.

"Why—you knew him well enough—"

"Oh, ay, sorr, Oi knows him well enough, as ye says. Don't Oi remimber him—the bothersome young spalpeen, as he used t' be! Will Oi iver forgit him? He's the wan they said had a gennious for invintin'—"

"That's right, Barney—"

"Wasn't he allus invintin' some fresh trouble an' botheration t' get me into ivery day whin he spent his holidays here?"

"I'm afraid that's true," laughed Harry. "But he's older, and less bothersome now, ye'll find. Though it's also true that he still prides himself on being a bit of an inventor. But you'll get on with him all right. He always liked you."

"Oh, ay, Oi'll get on wid him! I allus loiked him, too, in spite 'av his thricks. But I hope he won't thry his invintions on us. Didn't his uncle invint some newfangled explosive, as they said would blow a man farther off the airth than anny man had been blowed yit?"

"I believe he did, Barney, A most clever invention."

"Well, Oi don't know. Good old gunpowder's strong enough, an' cliver enough fur me. If a man were t' go on loike that, he moight blow the whole airth up into—into—well—it's little stars 'twould be, I expect, at the end av it."

Two days later Harry and his companion arrived at

Tamberton Court, young Sir Raymond's residence, on foot, having

walked from the station, where they had left their luggage.

Joseph Gower, the butler, opened the door, and stared at the two visitors in surprise.

"Sir Raymond's not in, my lord," he said. "He couldn't have expected you by this train—at least, he said he was uncertain—"

"That's all right, Gower," returned Harry genially. "My fault, I expect—I wrote and merely said I should catch the first train I could. Now where has he gone? Can we go to find him?"

"If your lordship pleases," said the well-trained old servant. "He is down at the pavilion on the island—where the old master had his laboratory. But I'll send—"

"Oh, I know my way. Don't trouble. I'll go and hunt him up myself. It will be a joke to take him by surprise. Come on, Barney."

And the two set off across the park in the direction of the seashore, which, Hurry knew, was not more than a mile or so distant.

Now, as they went on their way, Harry was asking himself one or two questions, and his thoughts led him to glance now and again at Barney, who strode on cheerfully beside him. Harry had written and told Ray that he was going to bring Barney, and he (Harry) was now cogitating as to whether Ray's absence from his home at the time of their arrival might have been intentional.

As Barney had not forgotten, Ray had been fond, in the past, of playing jokes on the old hunter. Had his chum—Harry wondered—some little joke in store for them now? It was somewhat curious—Harry thought—that Ray should so have arranged that his visitor had to go to seek him at the place which had been his uncle's laboratory and workshop—where all kinds of curious instruments and machines, no doubt, were to be found.

However, such speculations just then were vain; so he philosophically cast them aside, thinking that "time would show." As it did.

It was a pleasant morning in early spring, and the air was fresh and sweet. Stepping onwards at a swinging pace, they approached the shore and came in sight of the island of which the butler had spoken.

On this island—which lay in a sheltered little bay, separated from the shore by a strip of water two or three hundred yards wide—was a long, rambling building of two floors, partly modern, and partly very old. It had a high tower at one end which looked like the remains of some ancient castle. The rest of the building was in the style of a waterside pavilion.

In front, on the side facing the sea, a high, strong flagstaff rose from the shore.

A flag was hanging limply from the upper part of this mast, and there was a small door in the side of the building facing the mainland. The water between was smooth and inviting—but no boat was to be seen by which it could be crossed, the door was fast closed, and there was no one about.

The whole place looked deserted, and Harry began to think either Ray had not come there or that he must have gone away again before they arrived.

Not a soul was to be seen, either up or down the shore, who might direct them or answer a question. In the distance, on a headland, there was a lighthouse. Doubtless someone might be found there, but it was too far away to be of service to them just then.

"Well, this is lively! What on earth are we to do now?" cried Harry. "If Ray is there, why doesn't he show himself? How are we to let him know we are here? I can't see a boat anywhere. Can you, Barney?"

Barney could only shake his head.

"Not a sign av a wan, sorr, can Oi see," he answered. "Per'aps they expects visitorrs t' stand an' shout, loike they would at a ferry."

"Ah! That's not a bad idea," Harry agreed. "Perhaps they do. So let's shout."

They shouted, both of them. Barney called out "Ferry!" Harry cried, "Boat, boat!" and then "Ray, Ray, ahoy!"

But it was all in vain. No answer came back. No one appeared. The place seemed utterly lonely and untenanted.

Then Barney made a discovery.

"Shure," said he, "here's a post—wid a nothice- board!"

"So there is!" Harry muttered, going across to inspect it. "Let's see what it says."

He had seen it before, but thinking it was some ordinary "Trespassers beware" sort of notice, he had not troubled to go near it.

Now he found it bore a very different legend.

"To call the boat, please ring," it ran; and just below was a little white knob, with the word "Push" neatly printed thereon.

So Harry "pushed," and then stood staring across at the island, awaiting developments.

"Shure, there's a boat comin'," cried Barney suddenly, "but niver a person can Oi see in the same."

He proved to be right. From out of some hidden corner a boat had appeared, quietly making its way towards them across the placid water.

But neither oar nor sail was to be seen; nor was there any sign of human occupant. How it was propelled or controlled was a mystery. Nevertheless, it came on as steadily, and as straight, as though rowed by some ghostly oarsman, and steered by an invisible coxswain.

"Holy saints defind us!" gasped Barney, as he noted, with staring eyes, the boat's uncanny progress. "Phwat's sinding it along?"

Harry had to admit that he was himself no less puzzled. He could only watch with fascinated interest, while the mysterious craft gradually drew nearer and nearer.

Finally it ran alongside the landing-place, ending the little voyage as neatly as any human hand could have managed it.

"May Hiven protect us!" Barney cried.

"Shure, the craythure must be aloive! Will it spake next, Oi wonder?"

As though in answer, a large card suddenly popped up from somewhere inside the boat. Upon it was printed, in big, plain lettering:

PLEASE GET IN AND SIT DOWN.

"Oh, no fear! Not fur me!" exclaimed Barney, after he had made out the wording. "Faith! Thrust meself in a controivance loike that? No; it's bewitched, it is!"

He shook his head and drew back with such sudden haste that Harry could not help laughing.

"Come, come! I expect it's all right. Barney," he said, stepping forward, and looking into the boat with great curiosity. "It's evidently the way they manage things nowadays in this part of the country; only you and I have never seen it before, or we should have got used to it."

As he spoke he glanced across at the island, rather expecting to catch sight of his chum, Ray, watching them and enjoying their perplexity. But there was still no sign of life; the two windows looking that way had no peeping face behind the glass. The affair reminded him of fairy tales he had read about enchanted castles, where visitors were waited on by invisible hands.

He got into the boat, and sat down on a cross seat; and he noticed that the craft was pointed at both ends so as to go in either direction without turning.

Suddenly he heard a sharp click. The card vanished, and another one rose up in its place.

"All aboard? Hurry up, or you'll be left behind." was the legend which the fresh card displayed.

Barney, inspired by his master's example, had been about to risk it and jump in; but on seeing the card thus changing of their own accord, he drew back—or rather he tried to draw back. But Harry, who felt the boat moving, gripped him by the arm, and with his powerful grasp drew him forward, then bundled him unceremoniously into the middle of the craft.

There he tumbled on to the flooring boards, where he sat up, and looked helplessly and reproachfully at his young master.

Meantime, the boat had started, on its return journey, travelling smoothly and easily, without either jerk or vibration, while little ripples splashed merrily against its sides with a pleasant, soft, tinkling sound.

Suddenly there was another click, and this was followed by a whirring sound. It was like the preliminary flourish of a gramophone about to burst into metallic song.

Barney started, and grew more terrified than ever. He cast despairing looks at the fast-receding shore, then glanced apprehensively at the part of the interior the sound had come from.

The whirring sound increased in volume. And then, sure enough, a weirdly thrilling voice—albeit a little squawky in tone, perhaps—sang out:

"A life on the ocean wave,

A home on the rolling deep!"

Barney gave a great jump, nearly capsizing the boat. Indeed, it must have gone over but for Harry a presence of mind in rolling to starboard just as his startled companion had lurched to port.

The joyous, squawky voice ceased singing and called out:

"Barney, it's frightened ye are! Kape still! Ye're interruptin' me in me song—an' ye'll have the boat over!"

"Murther an' witchcraft!" moaned Barney. He took out a big, red handkerchief and mopped his forehead. "Did iver annybody see the loikes av this?"

Barney's face was such a picture that Harry roared with laughter. He knew now that Ray was somehow "engineering" all this, and was pretty certainly watching everything that went on from some concealed post of observation on the island—probably through glasses. Also, there must be a telephone on board connected with the pavilion.

Getting down on his knees he peeped and felt about under the seat round the end. And there he found what he sought. Partially concealed in a sort of casing was a curious, bell-like affair, something between the receiver of a telephone and the "trumpet" of a phonograph. It worked on a swivel, and he swung it out.

"Who are you?" he shouted into this contrivance.

"Shure, Oi'm the g-gh-ost av Bh-harney's brither!" came the answer.

Barney shivered and groaned.

"Ray, it's no use! I know your voice even through your cracked old trumpet!" Harry shouted back. "Come out into the open, and let's have a look at you, you rascal!"

The boat, by this time, was three parts of the way across, and was fast approaching the island; and, as he spoke, Harry glanced expectantly at the closed door of the pavilion.

Nor was he disappointed. As if in response to his demand, the door flew open, much as does the little door in a cuckoo-clock, when the bird pops out to "cuckoo" the hour.

But instead of a bird figure, there stood, framed in the doorway, as it were, the tall, sturdy form of Harry's chum, Ray Sinclair, smiling, bowing, and waving with his hands a graceful welcome to his visitors.

Ray Sinclair was, as stated, tall and sturdy, in which respect he resembled his friend; but in place of Harry's curly, fair hair and grey eyes, he had dark hair and eyes of clear, deep brown.

Perhaps his face was rather more thoughtful when in repose than Harry Temperley's, but as he came forward to greet the two, it was full of harmless, mischievous amusement.

He knew that he had roused their wonder and interest in the way he had received them, and he was evidently enjoying the joke.

The boat glided quietly alongside a landing-place and stopped; and by that time Ray was waiting to receive its occupants.

He shook hands heartily with Harry. Then, turning to Barney, shook his hand, too.

"Well," he cried briskly, "have you had a pleasant voyage?"

Harry laughed.

"You'd better ask Barney," he returned. "I'm afraid he was a bit upset. Anyway, he nearly upset the boat."

"Why, Barney, was it seasick ye were?" Ray asked the hunter.

"Arrah, now, doan't ye belave him, Misther Ray—if I may make so bould as t' call ye so. Misther Harry, he tould me to—"

"Quite right, Barney." said Ray, genially. "To you I'm merely Mister Ray—same as I used to be. I like it best so; it's more like old times. But you haven't answered my question."

"Shure, it's not say-sick I was, sorr; but I doan't loike witchcraft, an' magic, an'—"

"Well, that's all right. Now, are you hungry, either of you? Because if not, Harry, I'd just like to take you round the place. It's the only chance you'll have to see some of my uncle's curious machines and things until we come back from our travels."

Harry declared he was in no immediate need of refreshment. He would rather have a look round.

"Then come with me, Harry. But Barney wouldn't say 'No' to a little refreshment, I'll bet?"

He gave a peculiar whistle, and at once there appeared in the doorway a young negro, who came towards the three with eyes that showed the whites as he rolled them about, and a genial grin which revealed a fine set of white teeth.

"Tom!" said Ray quietly, "this is the gentleman I told you of. And that is his servant, Barney. Take him with you, give him a glass of milk, if he likes that best, and make him comfortable. Now, be off, the pair of you. I'll whistle when I want you."

The young darky's grin grew, if possible, wider than ever, as he made a half-military sort of salute to Harry; and then, putting an arm familiarly through Barney's, led him away.

"Come wit me, Massa Barney," Harry heard him say. "I'll take care ob you. You an' I's goin' t' be heap pals. Me show you lots o' fine tings—make you laugh, an' have good time."

"Hallo!" exclaimed Harry, as the two disappeared through the door. "Who's that? Where did you pick him up?"

"Took him away from a circus, where he was being badly treated," Ray replied. "The poor chap came over with a troupe to England from abroad, and he was made a slave and led a dog's life. I rescued him, and he's devoted to me now. I'm going to take him with us."

"Looks a cheeky young rascal. I should say he's 'all there,'" was Harry's shrewd comment, as they walked together towards the doorway.

Ray led his chum indoors, and up some stairs, to a large, lofty room with windows front and back, the former facing seawards, and the latter looking towards the mainland.

The place was evidently a combined workshop and laboratory. Around the floor were many weird and wonderful-looking machines; upon the benches was a collection of chemical apparatus; on the walls were boards with numerous switches; and, finally, there were two or three telescopes on stands. Ray laughed as he pointed to the switches, saying:

"That's the 'magic and witchcraft' which caused honest Barney so much perturbation, and, I expect, has been puzzling you. I merely turned those switches on and off, and so controlled the boat, while I looked at you through that telescope. Look through it and see how powerful it is! I could see the faces of you two as plainly as I can see yours now, and could read what you were saying by watching your lips. My gracious! You looked so comical, both of you, I was nearly bursting with laughter."

Harry peered through the telescope, and laughed, too. "Yes, I can see it's a most powerful glass," he said. "Splendid. Ray, you're a bit of a marvel."

A shadow fell on the young fellow's good-looking face, and for a space he became grave.

"Not I," he declared, modestly shaking his head. "It's dear old Uncle Ralph's doing! He taught me, you know. And it is in order to carry out his last wishes that we are going abroad."

Harry, now serious, too, nodded his head.

"Ah! You have not explained about that yet," he reminded his friend. "At present I'm quite in the dark as to what we're going for. Though, for that matter," he added briskly, "I'm jolly glad to have the chance of going with you, even if there were nothing particular to go for."

"It's a curious story," Ray returned musingly, "and I won't reel it out just now—time enough for that—but there's a spice of mystery attached to it which I don't understand myself. It's puzzling me a bit. Do you know, somehow, that young darky you saw seems to be mixed up in it!"

Harry stared.

"How can that be? What on earth can that nigger rascal have to do with it?" he asked.

"That's the riddle. And It's not him so much as the people I took him from that I'm thinking of. You know I told you I took him from a circus?"

"Yes. Well?"

"The show has been in this district for some time—in fact, it's still not far away. Now the people he was with, and who were ill-treating him, were Indians—an Indian troupe—and they came from—of all places—British Guiana—the place where we're going to! Now, is that a mere coincidence, or is there something at the back of it? That's what's puzzling me."

Harry uttered a long-drawn whistle.

"By Jove! That sounds strange!" he commented. "What reasons have you for thinking so?"

"Well, for one thing, these Indians—they perform with alligators and serpents, and so on—are the very same tribe as those I have to pay a visit to. And for another—"

Just then there came an outcry from outside. Barney's voice was heard raised in terrified accents, and he was calling on all the saints for protection.

The two chums hurried to the window facing the sea, which was open, and, looking out, they saw a curious sight.

The mast, of which mention has been already made, which was fixed on the shore, and rose out of a square, roomy platform, had an immense ball attached to it. That is to say, the mast ran through a hole in the ball, so that the latter could move up and down when made to do so by some hidden machinery.

It was, in fact, an affair like that at Greenwich Observatory, where the ball rises and falls at a certain hour every day, so that captains of passing vessels can set their chronometers to exact Greenwich time.

In the present case, Tom, who knew that the time was near when the ball would rise, had, with every appearance of innocence, persuaded Barney to get on the platform, and then climb on to the top of the ball, in order to "see what a lily-lily, bountiful! view"—as the young deceiver expressed it—could be had from that elevated position.

Then Barney had felt the ball tremble and begin to move. He had instinctively put his arms round the mast; and was now, as the two chums looked out at him, slowly rising in the air shouting and groaning with bewilderment and fear.

As to Tom, the mischievous cause of his plight, he was down on the shore, simply dancing with delight, rolling his eyes, and clapping his hands.

For some moments neither Harry nor Ray could speak for laughing, so ludicrous was the figure cut by poor Barney, and so extraordinary his antics, as he was forced, farther and farther, upwards. Finally, the ball reached the top of the mast, and remained there.

Then Ray shouted to him not to be alarmed. All he had to do was to hold tight, and in five minutes the ball would duly descend, and he would be able to get back on to the platform again.

"Can't we get him down before?" Harry asked, when he could control his laughter.

"No; it's worked by an electric current from Greenwich." Ray explained. "It rises at five minutes to one, and sinks again precisely at one o'clock. But Barney will be all right if he sticks to the pole. This is that rascal Tom's doing—you can see that."

But a strange Nemesis was to fall upon the larking young negro. There was a sudden rush, several figures appeared unexpectedly on the beach, and darted at the laughing youngster.

The figures wore strange costumes, and had dark-red complexions, and uttered weird cries in some unknown tongue. In short, they were Indians!

Ere the two at the window above well grasped what was happening, the strangers had seized upon Torn, and, in spite of his struggles, were carrying him off to a boat which had stolen up to the island unperceived and was lying just round the corner behind the other end of the pavilion.

"Quick! We must rescue him!" cried Ray. "There's a motor-boat below, Come down with me, and we'll go after them! This is monstrous—outrageous! They sha'n't have that youngster again to ill-treat and torture. We must get him back."

"I'm with you there!" exclaimed Harry. "We'll get him away from them if we have to fight the whole impudent gang!"

By the time they had reached the place where Ray's boat was housed. Barney had come down, and at their call ran to join them.

In a moment he seemed transformed. All his fears and annoyance had fled, and he was now the alert, cool-headed, determined hunter, ready to meet the Indians on their own ground, so to speak, as he had done with others like them, years before, in their native wilds.

"Shure, we'll git the young imp out av their hands, Misther Ray. It's meself as knows how t' dale wid them gentry!" he cried.

RAY led his chum to a boathouse on the shore, where lay a motor-boat ready for use at any moment.

"Here we are, Harry," he cried, as he himself sprang on board. "Just unhitch that rope while I start the engine! Those beggars have got a long start, and they carry a big sail, but I think we ought to be able to catch them up before they can get away."

Lord Harry cleared the mooring-rope, and as he jumped in he was followed by Barney, who came racing along and scrambled on board just as the boat began to move.

"Bad scran t' the spalpeens!" he muttered, shaking his fist at the craft they were about to chase. "Phwat would they want t' be doing now wid that young nigger?"

"That's just what I can't tell you, Barney," Ray answered, "except that I've no doubt they want to revenge themselves on the poor lad for leaving them and coming with me. That's why we must get him out of their hands at once—before they have time to do him any harm."

Barney nodded.

"You'll find a pair of marine-glasses in that locker, Harry," Ray added to his chum. "Just get them out, and have a look at what those people are doing. My hands are full, and I want to know what they're up to."

Harry found the glasses, and peered through them at the Indians in the boat ahead. Then he uttered an angry exclamation:

"They're tying him up," he said. "And none too tenderly! I saw one of the beggars strike him! I'll mark that fellow, and make him feel sorry when we catch him!"

Though he had seen so little of the negro, yet, he had already got to like him.

The youngster was, he could see, a genuine child of nature, brimful of fun, and possibly of mischief, but with a lot of good feeling lying beneath. Harry, who was a quick, shrewd observer, had noticed the look he had cast at Ray when he had first appeared. It was full of love and loyalty—the eloquent, faithful look one sees in the eyes of a Newfoundland dog when watching its master.

Harry loved his old schoolfellow with a whole-hearted affection, and was ready to like and trust this waif from other lands for that one look alone.

Meanwhile, the two boats were racing along, parallel with the shore, at a good speed, for the breeze was freshening each moment; and this was in favour to some extent of the fugitives. It increased their pace, while the rising waves hampered the much smaller motor-boat.

The water was growing more lumpy, and the little craft began to ship so much, as she tore through it, that presently Harry had to start Barney bailing.

"Where are we going—or rather, where are they going?" Harry asked dubiously. "They show no sign of any intention to land."

"No; that's what's puzzling me," Ray answered. "They seem to have some game of their own on which I can't fathom. I suppose, though, they'll be going ashore eventually; so we can follow them up later, even if we can't catch them on the water."

As he spoke, Ray was scanning the distant horizon, as though looking for something. Harry noticed it, and asked what he expected to see.

"Why, my yacht, the Swallow," he said tersely. "It's just on the cards that she may turn up in time to head off these johnnies."

"Your yacht!" Harry repeated, a bit bewildered. "I didn't know—"

Ray laughed.

"A little surprise I was going to spring on you old chap," he said. "I did not tell you, but we're going on our travels in style—in our own private yacht. And she's—well, never mind; you'll see for yourself when she appears."

"You rascal!" exclaimed Harry. "Fancy keeping a thing like that secret! Well, there's no time to rag you about it just now or to ask questions. Just you wait! Hallo! What's that coming up yonder? Is that your mysterious yacht?"

They were just rounding a headland, and in the distance could be seen a vessel in full sail coming towards them. Harry caught up the glasses and directed them at the stranger; but Ray took only one glance, and then uttered an exclamation of disappointment and vexation.

"No; that's not the yacht," he said. "It's a sailing vessel—a schooner—and—. By all that's wicked, she's waiting about here for those Indians! Look! They're heading straight for her!"

Sure enough, the boat they were chasing had altered her course, and was turning away from the land and steering towards the stranger, which was much farther out.

"They must have friends on that vessel," Ray went on. "If they get to her first, and take poor Tom on board, we're done! And it doesn't look as if we can overhaul them in time!"

It certainly did not; for though the motorboat was gaining, it was not doing so at a very fast rate. And the worst of it was, nothing could be done to increase its speed.

Ray and Harry looked at one another. Their faces were stern and set.

"Well," muttered Harry, "if they get on board, we must follow them."

But Ray shook his head.

"Depends upon where they go," he pointed out. "If they put out to sea we're done. We can only follow if they hug the coast; and that they're scarcely likely to do."

It was certainly anything but a hopeful position. Most persons in their situation would probably have given up any further attempt to follow the Indians.

Now that they were going farther out, the sea was getting rougher, and the motorboat was taking in more water. The three in her were already nearly wet through from the flying spray. And now the wind freshened still more, so that their position was growing dangerous as well as uncomfortable.

And, after all, why were they taking all this trouble, and why should they run further risk? Merely on behalf of a negro lad who had no claim upon either of them!

But no idea of turning back or giving in entered the thoughts of these sturdy, determined young Britons. They only set their teeth and held on their way; but Harry had now to join Barney in the work of bailing.

Suddenly the Irishman uttered a shout.

"Shure, here's another av thim!" he cried.

Ray and Harry had been so intent on watching; with grim interest, the sailing boat and the schooner she was making for that they had not looked to the right or the left for some minutes. Now, at Barney's words, they glanced in the direction of another headland, and there saw a second large vessel.

Owing to the nature of the coast at that part, she had not shown up very clearly. Now, however, a white streamer that was floating in the air above her indicated that she was a steam- vessel.

Harry seized the glasses and stared at her; but Ray did not need them.

"Hurrah!" he cried. "That's the Swallow!"

"What—your yacht?" Harry asked.

"Rather! And she's coming to take a hand in this little game. She's seen us! Markham—that's the master—my navigating captain, you know, must have been keeping a pretty sharp look-out. I'll raise his screw for this."

The yacht was coming towards them at a great rate. There were black clouds now pouring out from her funnel and mingling with the white vapour from her steam-pipe. From her bows two fountains of foam curled and seethed and hissed as they raced past her sides.

"Hurrah!" shouted Ray again, "She's going to head them off! Now, my beauties, the tables are turned! Ah! I thought so! They're steering towards the shore. Now's our chance to head them off on that tack, too!"

The Indians had evidently grasped the fact that the yacht was bent on cutting them off from the schooner; and, in fact, would do so if they held on. So they gave up the idea of reaching her, and had decided to try to gain the shore before the motor-boat could intercept them. As to the yacht, they knew she would not dare to follow them far into the shallow water.

The new race which followed was a swift and exciting affair. The motor-boat had to cross over at an angle, and was therefore at a disadvantage; but, on the other hand, the nearer it approached the shore the smoother the water became, and the greater its speed.

Presently the sailing-boat was within two hundred yards of the beach, with the pursuing craft only about the same distance away. Still, the former was now fairly safe, for it was scarcely possible for the other to catch it up in the distance that was left.

Ray and Harry uttered smothered exclamations, and the latter stood up. Barney was talking to himself, gabbling away incoherently; and then suddenly he gave a great shout. There had been a splash ahead of them. Something or someone had gone overboard.

And Barney had seen what—or rather who—it was. It was the young negro, who had cunningly managed to wriggle himself from the cords that had bound him, and had leaped into the sea.

For a few moments no further sign of him could be discerned; he had dived, and was evidently cunningly swimming under water as far as possible.

But another figure rose up in the sailing boat and dived into the waves. One of the Indians had plunged in after the young nigger.

Then there was a splash beside the motorboat, which had now come so near to the place where the lad was swimming that Ray shut off the engine. The splash was caused by Harry, who had sprung in to aid the youngster against the Indian.

Another Indian followed the first, and Barney, with a wild whoop, plunged in to help Harry; so that there were, by this time, four in the water at once.

The sailing boat, unable to stop quickly like the other, had forged on ahead, and though the sail had been promptly lowered and oars were got out, she could not turn and get back in time to take any part in the struggle which followed.

What precise form that contest took none of the onlookers could probably afterwards have clearly stated. There was much splashing and diving, some amount of determined fighting, during which Ray fairly danced about with excitement, seeking some way to aid his friends, but finding none that seemed effective.

He dared not jump in himself, as it would have been folly to leave the boat to itself; and the most he was able to do was to fling things whatever he could catch up—at the two Indians. Unfortunately, being afraid of hitting his friends instead of their enemies, his assistance in this direction was not of much value.

The Indians in the sailing boat had brought her round, and were beginning to row back, when shouts not far away caused them to pause.

The yacht had drawn up as near as her skipper thought safe, and a boat had put off from her, and was now coming towards the scene of strife, urged along by four stalwart rowers.

Then the Indians in the water broke away and swam to their boats, which once more headed for the shore.

Harry and Barney were then seen swimming towards the motorboat, holding up the negro lad between them. And it was well they were there to help him, for he had been struck by some missile thrown by one of his enemies, and half stunned.

However, they, with Ray's aid, got him safely on board, just as the boat from the yacht ran alongside.

In the stern sat a stout, bluff, seafaring man with a weather- beaten, clean-shaven face, whom Ray introduced to his dripping chum as Captain Markham.

"You'd better come back to the yacht with me, my lord," said Markham, "and change your clothes for some dry togs. Unless, sir," he added, with a glance at Ray, "you want me to follow up those dark-skinned pirates, yonder," indicating the Indians.

"No, no, Markham," said Ray. "Let 'em go. We've got the lad; and, as you say, Lord Harry needs a change. So do these other two. We'll all come on board, and you can let one of your men take charge of this boat."

"Ay, ay, sir!" was the skipper's prompt response. And a few minutes later the whole party were mounting the ladder to the yacht's deck. And here a fresh surprise awaited Ray's chum.

As he stepped upon the deck a young girl—quite a child, and daintily dressed in a blue and white yachting costume—came forward and gravely greeted him. She was holding a pair of glasses in one hand.

"Thank you, sir," she said, with a charming mixture of diffidence and friendliness. "Thank you for what you did for poor Tom. I was looking, and saw. Oh, it was very, very brave and good of you! I wonder if Tom has thanked you?"

She turned to the negro, who was now standing near, wet and dripping, but otherwise none the worse for his adventure. Indeed, if anything, he seemed more perky, and his grin was wider than ever.

"Me not tank de gentleman bery much, Missie Eva," he volunteered. "Um mouth too full ob de salt water. Me no love drinking salt water. S'pose you tank him for me?"

"Get along, you cheeky young rascal!" exclaimed the skipper. "Is that all the gratitude you have to offer Lord Harry for risking his life for you?"

"Lord Harry!" repeated the child, wonderingly. "I've heard about you. Sir Ray told me what a very nice man you are. You're his friend—his great friend, aren't you? So you must be my friend, too; because I like him very much."

Harry laughed. "Why, of course I'll be your friend, my little lady," he replied. "But—who are you? Tell me your name."

Here a young man—also attired in a yachting suit—stepped forward, laughing.

"She is my sister, Eva, Lord Harry," said he, extending his hand. "I hope you won't be offended at her patronising you as she has been doing. It's a way she's got. We've all got to put up with it."

Harry turned in wonder. He had not seen the young man standing there.

"Why Lowther," he said, heartily, as he shook hands. "Fancy meeting you here! This is another of the numerous surprises Ray has sprung upon me to-day. And so this is your young sister! I don't wonder that she queens it over you. I've fallen under her spell myself already. What—if I may ask—are you doing here, you two? Just out for a morning sail?"

Harry had known young Lowther at Oxford, but had only seen him once or twice since leaving the university.

Ray answered for Lowther, and said that he and his sister were going to be their companions for a little while.

"His father and mother, and his other sister," he explained, "are coming over from America with the American millionaire, Mr. Vanderton, and his family in their yacht. We shall meet them on our way out, and put Lowther and his sister on board. See?"

"Capital, capital!" cried Harry. "We ought to be quite a jolly party together! And now I'll go and get these wet clothes off."

LORD HARRY'S words came true—they were quite a jolly party on board the Swallow when, a few days later, she set sail for America.

He made a friend of Captain Markham, whom he found to be a good fellow, a skilful seaman, and very proud of the yacht he had charge of.

Well, indeed, he might be, for she was a splendid vessel, fitted, as Harry quickly found, with all the latest appliances and inventions, from wireless telegraphy to a water-plane. Indeed, there were several clever and useful contrivances on board which were so new that they had not yet become known to the world generally.

As for Gerald Lowther's young sister, Eva, she was enjoying herself immensely. She was not troubled with sea-sickness, everybody liked her and petted her, and—finally—she was going to meet her father and mother and sister, whom she had not seen for nearly a year—for they had been travelling abroad all that time.

In a few days the Swallow had got so far on her outward journey that they were hoping to pick up a wifeless message at any hour from the Iris—the large yacht they were to meet; and both Eva and her brother were in a state of eager expectancy.

They, of course, were anxious to know, in the first place, that all was well with the Iris and those on board; and, beyond that, they were looking forward to having "a chat by wireless"—a strange marvel to them in itself—and to exchanging news on both sides.

Meantime, Eva had found plenty to do. Sometimes she was fishing over the side with Barney and Tom, getting together a collection of wonderful kinds of seaweed, which Harry showed her how to preserve in a special album made for the purpose.

At other times she followed the captain or his officers about, asking questions, and, if they were not too busy, receiving replies which added immensely to her little stock of information about ships and shipping and the sea generally.

And she reigned over them all, for the time being, as Harry had put it, like a little queen, carrying a feeling of sunshine and pleasure wherever she went, and giving back to all alike, rich or poor, masters or servants, bewitching smiles and beaming, delighted looks for the slightest kindness or little service offered her.

"Oh! Here you are, Eva!" cried Harry, coming upon her suddenly on the deck. "I've been looking for you! They've got in touch with the Iris, and everybody's right as nine-pence on board! There's a message from your mother for you; and one from your father for your brother. We must find him at once."

Brother Gerald was quickly found, and Ray, too; and then the whole party trooped into the wireless operator's little office to hear the news and exchange messages with their friends.

Now these little details are noted here chiefly because of the exciting and trying experiences which followed, and which brought home to all concerned the uncertainties and dangers of ocean travel—the sudden and unexpected perils which lie in wait for those "who go down to the sea in ships."

It was yet early morning, though quite light, when Captain Markham entered Ray's private cabin and woke him quietly.

"Why—what on earth's the matter, Markham?" exclaimed the young owner of the yacht. "Your face is enough to scare—"

But the worthy captain laid his fingers on his lips with an air so grave that Ray became serious at once.

But had started up scarcely quite awake, he had had, at first, a hazy idea that the skipper was playing some little joke upon him. Perhaps he (Ray) had overslept himself, and the captain had come with a solemn face to tell him that breakfast was long since over.

"There's bad news, Sir Raymond," Markham said, in hurried accents, hardly above a whisper. "Don't speak loudly—I don't want others to hear just at present. Maybe it will turn out later to be better than it looks just now. Can ye come to my cabin, sir?"

Ray hastily threw on some clothes, and followed his skipper to his private cabin.

On the way he vaguely realised two or three things; one was that it was still very early—not long past dawn. Another was there had been a great change in the weather; from being fine, warm, and calm, it had become rough, cold, and foggy.

The yacht was tumbling about in a heavy sea; the wind was gusty and there was a driving sea mist which shut out the horizon, and, indeed, prevented them from seeing more than a mile or two in any direction.

Ray remarked upon the latter.

"It's been a bad night, sir; worse than it is now," Markham answered, as he closed the door of his room behind him. "Very thick—the sort of night when ships are apt to run into one another."

He said this with such an evident suggestion of a deeper meaning that Ray became really alarmed.

"Something has happened, captain?" he said quickly, and, as the other nodded gloomily, he exclaimed: "Something wrong with the Iris? For heaven's sake, man, don't keep one in suspense! Tell me—is she—is she—"

"Indeed, sir, I do not know how things are at this moment; I brought you here to tell all there is to say, and then to ask you to decide what shall be done about telling the others."

Not long before, he went to say, they had received a wireless message headed "S.O.S." It had come from the Iris, and stated that she had been run into, in the dark, by an unknown vessel, which had slipped off into the night without offering help, or even inquiring what damage had been done.

"The message had just got as far as that, sir," Markham explained, "when the current seemed to fail—or something went wrong with their apparatus. It tailed off into nothing. I told Curtis to stay on the watch, and let me know at once if anything more came through, while I came to call you."

The two stood and looked at each other with eyes which told of thoughts neither dared to put into words.

"And—the message did not give you the bearings of the Iris?" said Ray at last. "We can't go to her assistance if—if—"

He meant "if she was still afloat," but somehow his tongue seemed to refuse to say the words. The mere fact that the message had been headed "S.O.S." told that the senders must have considered themselves in grave danger.

"Perhaps, Sir Ray," the captain went on, "the wireless outfit may have been damaged, and they may be repairing it. I hope and pray that that may be the reason of our hearing no more. I pray to Heaven it may be so."

"I must go and rouse Lord Harry," said Ray, after an interval of silence. "I must consult him—and then we shall have to break the news to Mr. Lowther. We must tell him, of course."

"Of course, sir."

"But, meantime—can we do nothing? Can we not go in search of the Iris?"

"I'm doing all I can, sir—all I dare do in the circumstances," Markham returned, "I've put on speed—ye must have noticed it. We are running fast—as fast as this head-wind will let us; but we're in a difficulty, ye see. We might overshoot the mark. I was going to suggest firing a gun now and again. But I couldn't do it till—till ye'd told Mr. Lowther."

"No; I see. Of course not. Well—I'll see to that at once. He must be told, of course."

At that moment, even as Ray was turning sadly away, a seaman came to the door of the cabin and knocked; then he opened it, and spoke hurriedly.

"Sir, sir. Mr. Curtis 'as got her agen. He sent me to tell ye, an' t' ask ye t' come quick!"

There was a fervent "Thank heaven!" from both men, and at once they scurried off to the box of the wireless operator—Curtis. The seaman's words had been rather "mixed," as it were, but they understood him. He meant that Curtis had had another message from "her"—"her" meaning the Iris.

How grateful, how relieved they felt, can be better imagined than described. They were still terribly anxious; but anxiety was very different from the black despair that had been settling down on their hearts.

Curtis, they found, was fully as anxious and excited as themselves.

"She's afloat, sir!" he burst out. "And I've got her bearin's, and she isn't very far away—nearly ahead of us, as far as I can guess. But you will be able to tell better than I can, captain. I've written it down here." And he handed the skipper a sheet of paper.

"Ay, ay!" muttered Markham, as he scanned it. "We're on the right track. But it don't say—"

Curtis raised his hand to enjoin silence. He had clapped the ear-piece on to his head again, for he knew that yet another message was coming along.

"Write it down, sir," the young man said. And Ray seized paper and pencil, and waited in eagerness:—

"Thankful to hear you are on the way. (That's in reply to a message I sent, sir," Curtis explained rapidly.) "How long will you be? Fear our ship is sinking, though slowly. Wireless machine damaged, got it going again, but still not reliable. Our boats badly damaged, and one missing. Hurry all you can, or fear the worst. All on board well otherwise, except a few slight injuries.—H. Martin, captain."

"I'll see the chief engineer, sir, and tell him to drive his engines for all they're worth. An' I think we'd better fire our gun," said Markham. "They may hear it on board the Iris, and fire theirs in return, and that may help us t' find 'em. Otherwise—in this fog—ye see, it'll be like lookin' for a needle in a bottle of hay."

Ray nodded his head. "Do all—everything you can, Markham," he urged. "Run risks if needful. We must save them, man, we must save them!—or how shall I ever be able to look that child in the face again? Poor kid! Poor little Eva!"

The captain nodded in silence. There were tears in his eyes, and in Ray's, too, as he went off to find Harry and Lowther, and break the news to them.

THE steam-yacht Swallow was threshing her way through a heavy sea, and against a nasty head-wind which brought with it a driving sea mist. In this fog she was trying to find the Iris, and her engines were being driven at their utmost speed, but no success had attended the efforts made. Those on board began to despair.

It was now getting on towards noon, and still the mist, which had so hampered their movements, continued to impede their view of their surroundings. To make matters worse, no further wireless message had come from the yacht they were seeking for several hours.

Had the Iris already foundered, with all on board, or did it only mean that her wireless machinery had again failed?

This and other anxious questions were being asked by all on board the Swallow. By all, that is, perhaps save little Eva Lowther. She, so far, had been kept in ignorance of the fact that the Iris, on which her mother, father, and sister were travelling was in a sinking condition.

Her brother Gerald had not dared to tell her, no one else dared to do so; but very difficult they all found it to keep up a cheerful appearance before her. She only knew—or guessed, from the sombre looks she caught now and then on the faces of her friends, that something had gone amiss.

Presently her brother managed to persuade her to start sticking some seaweed in one of the books she was using for that purpose, and, having seen her well engaged upon this occupation, he returned to the deck to seek such solace as could be found in the company of his friends there.

Lord Harry was walking up and down with a quick, nervous, uncertain tread, very different from his usual measured, easy step. His chum, Sir Ray, was running backwards and forwards to the little office of the young wireless operator, Curtis. Each time he went there his face lighted up a little with hope; but each time he returned it wore, if possible, a yet more gloomy expression.

Now and then the brass cannon on the fore deck sent out a sullen, deep, booming note, which, however, did not seen to carry as far as usual. The heavy, damp sea fog appeared to act like a wet blanket, and to muffle the sound and prevent it from travelling.

Captain Markham was in the chart house, with a slate before him covered with figures in a manner which would have made ordinary people giddy even to look at. But the way he kept starting and going to the door and looking about, expecting—or hoping—for something which never came, showed that he was unable to keep his mind upon his work.

Then, unexpectedly, another message was received, and the anxious ones gathered round Curtis to hear it read out. It was more urgent than the last that had come to them, for it said that the Iris seemed to be gradually settling down, and imploring the would-be rescuers to hasten.

Gerald was becoming distracted, so was the captain; and so, it may be said, were all on board—with the exception of the child—for Fate seemed to be working against them.

Vainly did the captain pore over his slate and his bewildering array of figures—he could not hit off by calculation exactly where the Iris lay, and the fog still prevented their seeing anything farther than half a mile away.

"What can we do, what can we do?" Ray asked, for the hundredth time, of no one in particular. "This is awful, terrible! To think we are so close, as Markham says he is sure we are, to the Iris, and yet we can't find her."

The yacht had now stopped, or very nearly. She was only going just fast enough to keep steerage-way on her; for the captain declared it would be a mistake to go away from that part. So she was travelling slowly in a wide circle, hoping thus to come across the vessel in distress.

Harry had asked Curtis to send a message: "We are firing our cannon at intervals. Are you firing yours in return? We cannot hear it."

Curtis had sent the message, but no reply had come to it; and he expressed the opinion that the machine on the Iris must have failed again, and was once more too weak to receive the current, or to send off any answer.

To Eva, seated at a table in the saloon, with her book before her, there entered Tom, the young negro. He stole in cautiously, for it was forbidden ground for him at other than meal times, when he was wanted to help wait at table. Eva, looking up, saw his eyes peering round the door like two shining black beads set in a milk-white frame.

"What d'you want, Tom?" Eva said. She was glad of an excuse for desisting from her occupation. And she frankly said so when Tom, in return, asked what she herself was doing.

"The boat rolls about so, and the table goes up and down in such a nasty way—it makes my head ache," she complained. "By the way, can you tell me what they are firing that wretched cannon for?" she asked. "That's another thing that is giving me headache; it makes me jump every time it goes off."

Now Tom, partly because he was a youngster, and partly for fear he might blurt it out before Eva, had not been told anything, and knew nothing of what was going on, except what he saw and heard.

There was the firing—and there was the ship almost stopped; and there, as he said to Eva, "was all de folks lookin' so glum an' cross, as if dey all feel bery ill."

And as to the firing, he was just as much puzzled as Eva, because, as he put it again, "dey fire at noting—dere is noting to shoot at, an' noting to see."

Perhaps, however, he speculated, it was a match—their ship was "trying to make more noise dan de oder ship."

"What other ship do you mean, Tom?" Eva asked, with a yawn; this had been a very dull, uninteresting morning for her. "I haven't heard any other ship firing, and I did not know there was one near.

"Me hear it lily much times. Dere! You hear dat? Dat's de oder ship!"

But Eva heard nothing of the sort, and, as she supposed she would be able to hear better on deck, she left the cabin, and Tom went his way.

Eva, however, found she could hear no better on deck than down below, and began to think Tom had been playing tricks upon her.

She asked Harry's opinion, and Harry, at first too abstracted to answer carefully, became more interested as she persisted in her questions.

Finally he sent for Tom, and requested him to explain himself; but it took a little while to arrive at the point that this young child of Nature could hear sounds the others on board could not hear. He had, in fact, been hearing them for some time, had wondered what they meant, and now wondered still more when Lord Harry suddenly seized hold of him and hurried him off to the captain's cabin. There they found Sir Ray looking at the captain's slate, and trying to sec if he could read anything new in the rows of figures.

There were questions and answers, and cross-questions, and some wondering talk on Tom's part, which ended in the ship's head being swung round and kept in a straight line for a while.

And then it was that the feverishly eager listeners heard, at first faintly, but soon more plainly, the occasional boom of a distant gun!

"Full steam ahead!" was at once the order telegraphed from the captain to the chief engineer, and the receipt of the signal was followed by the appearance of the skipper himself in the stokehole, much to the astonishment of his men. They were still more astonished at the way he made them work during the next half-hour.

But they did not mind this when they understood what the reason was. Indeed, they heard the "reason" itself ere long, as the deep boom of the distant gun grew plainer, and they heard it sending forth its urgent summons to the rescuers.

What a transformation the sound brought about! Faces that had been filled with heavy, sombre despair began to light up with the joyous throb of returning hope. Listlessness on the part of the crew gave place to bustling activity.

Nearer and yet nearer came the sound, and the eager listeners on deck hurried into the bows of the ship, straining their eyes in the endeavour to catch a first glimpse of the vessel they were seeking so anxiously.

The Swallow raced through the water as she had never done before, and her boats were swung out ready for instant launching when the time should come.

And then the mist suddenly lifted a little; the excited watchers could see quite a long way on either side, and there, almost straight ahead, lay the Iris.

What a rousing cheer went up as they all caught sight of her! How good it seemed to be able to cheer like that!

But it was better still to hear the answering cheer which came back to them. It told the rescuers at once that they were in time.

Then, to Eva's great surprise, Harry picked her up and kissed her rapturously; and Ray followed suit, and so did her brother.

She was surprised—not at the kisses, but at the way they were given, for she was still unconscious of the fact that it was through her artless chatter about what Tom had said that they had found the Iris.

They almost indeed felt ready to give Tom himself something in the nature of a hug perhaps, but his reward in that way was to come later.

"You will soon see your papa and mamma and sister Eva," said Lord Harry, in a voice that had a catch in it, as he set her down and hurried away to where the boats were being got ready.

By that time the Swallow had drawn as close as she could to the sinking vessel, and it could be seen that the rescuers had no time to lose. Already the doomed vessel was settling down; she had a bad list to port, and the stern was very much lower in the water than the bow.

The moment the signal was given Ray and Gerald took their places in one boat, while Harry scrambled over the side and dropped into another. Then, each pulled by two sturdy pairs of arms, they started on a friendly race, each boat striving for the satisfaction of being the first to reach the sinking boat's side.

Scarcely more than half an hour elapsed ere they had returned, bringing the first of the castaways; and the scene can be better imagined than described as they came on board, amid the resounding hurrahs of the sailors.

The rescuers started back at once, and in a short while the whole of the people on the Iris had been transferred to the Swallow.

Then, amid the congratulations and rejoicing, the rescued ones learned how their rescue had been brought about, and heard of the fateful results which had followed from Eva's little talk with Tom in the cabin.

Eva was clasped once more in the arms of her weeping mother—weeping, that is, with joy and thankfulness, and Tom was made much of, too. Indeed, Mrs. Lowther actually kissed him—an honour the young darky appreciated so much that he was filled with pride, and gave himself such airs that Barney was almost afraid to speak to him.

But they only fully realised how much they owed to the negro's quick hearing when, less than an hour afterwards, they saw the unfortunate Iris give a great heave, and then plunge, with a mighty swirl, beneath the waves.

"WELL, now, gentlemen, we want to know the whole story. How was it you came to be run down?"

It was Ray who spoke, and he was addressing Mr. Vanderton, the owner of the Iris, and Mr. Lowther, who had been his guest and friend on board.

"Well, now you've asked me something I can't tell you," returned the American. "I can only say that there's something tarnation mysterious about it."

There was that in the millionaire's tone which excited the strong curiosity of his hearers, which latter included Harry and Gerald Lowther.

They glanced at the speaker in surprise, and from him to Mr. Lowther. And it was Mr. Lowther who answered their looks of inquiry.

"The fact is," he said, in slow, grave tones, "there are some facts which are puzzling us, and for which we can find no satisfactory explanation. One of our party is missing—"

"Missing!" cried two or three voices in surprise.

"Yes, Mr. Jacob Harker, who was Mr. Vanderton's private secretary."

"Knocked overboard in the collision and drowned, I suppose, poor fellow," said Harry, feelingly.

"As to that, we can't say, my lord," Mr. Lowther returned. "We do not know what to think, because, as you have already heard, one of our boats is missing, too!"

"That certainly sounds strange," Ray commented thoughtfully. "Do you mean to suggest that he went off in the boat by himself, unknown to you?"

"Well, of course, we can't say for certain," said Mr. Lowther, with a glance at the millionaire, who was moodily smoking a cigar. "And Mr. Vanderton does not like to admit the possibility of such a thing. Yet what are we to think?"

"I can't believe that Harker would have gone off in a boat in the darkness by himself," muttered Mr. Vanderton gloomily. "Why should he? Anyway, if he did, he must have been mad at the time, for it was a mad thing to do."

"There's another mysterious point about it" Mr. Lowther went on. "The other boats of the Iris were all so damaged as to be useless. That was why we were in such terrible danger. We had not a boat we could turn to; and if the vessel had gone down before you arrived, you see our only chance of escape had been destroyed beforehand. Now that's a very suspicious circumstance."

"But I suppose they were injured in the collision?" Ray suggested.

"Well, there's the question. Thompson, the captain, thinks not. It is a bit difficult to say, but he declares it as his opinion that, though perhaps one or two may have been injured in that way, it was certainly not the case with all of them."

"That," remarked Ray gravely, "is as good as to say that they must have been injured intentionally—probably before the collision took place?"

"That is my own deliberate opinion," Mr. Lowther replied, with conviction. "It is also Captain Thompson's. But our friend here, Mr. Vanderton, won't listen to it. He says it is impossible."

The American, a tall, fine-looking old gentleman, with a quiet, pleasant voice and manner, bit his lip and shook his head.

"No," he said emphatically; "I don't want to believe anything of that sort, and I won't until it is proved beyond all doubt. See here! You know quite well that to say so is to accuse my secretary, who, as far as I know, has probably been drowned, poor fellow. It is difficult to say who else could have done it. It is, then, actually suggested that he smashed up all the boats except one, and then went off in that one, and purposely left us to our fate. Why, no one but a monster would do a thing like that! It is accusing an absent man, one who may be dead, and it does not seem a proper thing to do. Besides, after all, why should he do it?"

"I admit, my friend," said Mr. Lowther, "that that is the point which puzzles me. I cannot understand any more than you can why he should do such a thing."

"No, of course you can't, nor anybody else!" Mr. Vanderton returned. "He was a capital secretary, a most clever man, very civil, and attentive to his duties. We were very friendly, and I trusted him completely. Why, I repeat, should such a man attempt a crime of this nature, and seek to do me such an injury?"

"Perhaps he went suddenly demented," Harry suggested. "The shock of the collision may have upset his mental balance. Such things have been known to happen."

"The whole thing is an enigma, my lord," the millionaire commented finally. "And, as I fear there is no doubt the poor fellow is dead, we shall most likely never learn the real truth."

There the matter was allowed to rest, and the talk turned to other subjects. One of these was the likelihood of their encountering one of the big liners on her way to England.

Ray and Harry had conferred together, and agreed to return to England if it should be really necessary to land the castaways, and the yacht's head had been turned in that direction. But it was hoped that they would in the meantime fall in with some homeward-bound ship which would take them on board.

But the Iris had been a long way from the beaten track at the time of the accident, and the Swallow was therefore now heading towards England in a slanting direction, in order to try to intercept a liner; and a sharp look-out for other vessels was being kept.

It was blowing harder, and the yacht was tumbling about in a heavy sea, but the fog had cleared off, and the clouds on the horizon lifted towards evening.

There was even a gleam of sunlight, but the wind increased in force, if anything, and the captain shook his head. In his opinion, he said, it was likely to be "a dirty night."

Presently, however, the clouds lifted still more, and the setting sun shone out in all its golden splendour, gilding everything it fell upon a rich ruby-gold tint.

And one of the things it touched and thus lighted up was a floating wreck—the hull of a stout-built steamer, with masts broken off to within a few feet of the wave-washed deck.

And there, lashed to the stumps, were three men—whether alive or not it was difficult to say. Certainly they could have had, at the best, but very little life in them, for they hung limp and listless, swinging this way and that with every lurch of the rolling wreck.

It was a painful sight. All those on the deck of the Swallow at the time were filled with sympathy, and watched the poor creatures with bated breath.

"Are they alive?" "Can nothing be done for them?" "Can't they be rescued?" These were some of the questions asked eagerly and excitedly, albeit but a little above a whisper.

Just then one of the three unfortunates seemed to revive a little. He held his head up and gazed round, and he must have caught sight of the yacht, for he joined his two hands and lifted them in mute appeal.

Mr. Vanderton uttered a startled exclamation. He had been looking at the three through marine-glasses, and had noted something vaguely familiar about this particular man. He was clad in better clothes than the other two, who were evidently sailors; and at a second glance the millionaire recognised him.

"Harker!" he cried. "It's Harker! It's a strange thing how he should come to be on board that wrecked vessel. But he must be saved! I'll offer—"

Harry put up his hand in protest. "No need to offer any reward, I should say, Mr. Vanderton. Of course, the poor fellow must be saved. We'll send a boat at once—eh, Ray?"

Ray nodded his head, but before anything more could be said Captain Markham came up.

"It'll be a ticklish business, my lord," he declared. "But we can ask for volunteers. It's as much as any boat can do to live in such a sea."

"We'll have a good try, anyhow," Harry answered. "I'm ready to go, for one.

"And I," cried Ray and Gerald Lowther.

"No need for all to go," Markham pointed out. "One of ye'll be enough, with some men for the oars."

"Then we'll have to cast lots!" exclaimed Harry. "And we can do that while the boat's being got ready."

As there seemed no other way to settle the matter—all being equally eager to help and equally obstinate in refusing to give way—lots were drawn, with the result that the choice fell upon Harry.

A few minutes afterwards the boat left the ship's side, watched with tense interest by everybody on board.

It was a terribly hard struggle, and often the hearts of the spectators came into their mouths as they saw the little craft sink down between two great waves and disappear from sight.

There would be a long-drawn gasp of relief as it was seen climbing up the next wave. A hush as it poised on the foaming crest, and another gasp as it took the dizzy plunge down the other side and once more disappeared.

This was repeated again and again, till at last the boat approached the heaving, tumbling wreck. And then came what was really the hardest and most dangerous part of the adventure.

It was impossible to run alongside. The boat would have been smashed to pieces at once. So it had to be manoeuvered round to the lee side, and kept there, as well as the rowers could manage it, while the castaways were somehow got into it.

But this was where the great difficulty lay. The men on the wreck were helpless. They had not the strength to cut themselves loose, jump into the sea, and swim to the boat. It became necessary that someone in the boat should swim to the wreck and climb on to it, taking his chance of being smashed against the side of the hulk in making the attempt.

Even the hardy, sturdy men of the crew shrank from this; and when Watson, the first officer, who was technically in charge of the men, called for a volunteer, there was no response.

"No need to trouble, Watson," said Harry. "I'm going myself."

"You, my lord!" exclaimed Watson. He looked aghast at the idea. "You mustn't think of such a thing, my lord! It—it's—"

"It's no worse for me than for anyone else," laughed Harry, throwing off his yachting jacket. "It won't be the first time I've had a swim in a sea like this. Then it was only for fun and pleasure. Surely I may do as much now when there are these poor fellows' lives at stake! Hallo! What's up now?"

This last exclamation was drawn from him by the fact that something or someone had suddenly risen up from beneath a heap of cordage and canvas in the bow, and plunged overboard.

There was scarce time to see what or who it was. It went like a streak—not a light streak, but a dark one. Harry rubbed his eyes, half wondering if he had really seen what he fancied he had.

For it was Tom who had thus suddenly appeared and gone over the side. No one had known that he had been there. How he had concealed himself seemed a marvel. There, however, he was in the water, swimming for the wreck as hard as he could go.

And Harry saw that, he had taken a rope with him.

"Come back, you young rascal!" he cried. But, of course, there was no response. The howling wind drowned the words, or carried them away, so that they were scarcely heard even by those in the boat.

The next moment Harry had dived in, and was swimming vigorously in the wake of the negro, with a hold on the line, thus aiding to drag it through the water.

Harry wanted desperately to catch Tom up and to order him to go back, under all sorts of dire penalties. But he tried in vain. Tom reached the wreck first, clung to its side like a limpet, and finally climbed on to the slippery deck.

There he coolly turned and held out a hand towards Harry as though to help him. And, by the way he rolled his eyes and grinned, he seemed to think the whole affair a vastly amusing joke.

As a matter of fact he did aid Harry in climbing up on to the heaving deck, though how he—Tom—contrived to cling on himself the while was a puzzle.

Once on the deck, however, the two lost no time. They pulled upon the light line Tom had brought, and Harry was greatly relieved when, at the end of it they came to another one, much stouter and stronger, as well as a second light one. The stronger one was pulled in far enough to make fast to the stump of the mast the men were lashed to. Then Watson secured the other end to a thwart; and so managed the boat as to keep the line fairly taut without putting too great a strain upon it.

Now came the task of getting the three castaways to the boat. They were able at first to assist but little themselves, though they roused up considerably when they found that there was really a chance of being rescued.

They were all bruised and knocked about; indeed, as it afterwards turned out, Harker had been badly stunned, and was still suffering from the effects of concussion.

There followed a terribly hard fight with the cruel sea for the lives of these three men.

Inspired by the example of Harry and his companion, one of the sailors in the boat plunged in, and started to their assistance. He carried a third line—for Watson had taken care before starting to have a good supply of rope—and, aided by the stout cord which had been fixed to the mast, made the passage in safety.

Harry saw him coming, and grasped his hand as he clambered up the side.

"You're the sort Nelson would have liked to shake by the hand, Reid," he said cheerily. "But now comes the tug-of-war—the sea'll have these men, or one of 'em, if we're not careful."

"Naw, naw, not wi'out it takes me, too! Heaven helping us, we'll pull 'em through, me lord!"

It was literally a case of "pulling through." The men had to be first secured by tying a line round their bodies, and then hauled through the tumbling waves by the people in the boat, the while that the three brave swimmers supported them in the water as best they could.

But it was done at last. They were lifted into the boat, one after the other, which then set out for the yacht, and, after another strenuous battle with the wind and waves, reached it in safety. There the rescued men were handed over to the care of the ship's doctor.

By the time this was done darkness had settled down on the scene, and the chief actors in it were glad to seek their berths and get some sleep; for they had had a trying twenty-four hours, and were tired out.