RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"Cadets of the Dolphin," Boys' Friend Library, Octoer 1915.

"Cadets of the Dolphin," John F. Shaw & Co., London, 1925, Book Cover

"Cadets of the Dolphin," John F. Shaw & Co., London, 1925, Title Page

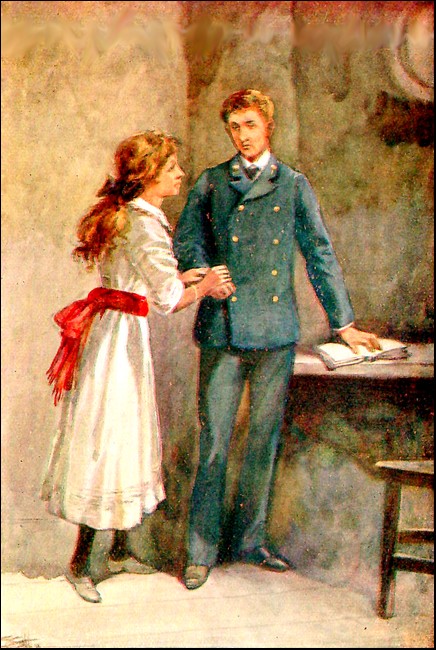

Frontispiece.

Mr. Melfort glanced at Jack with evident interest.

"HULLO, Branson! Who'd have thought of seeing you up here! Thought you were away yachting with your dad! Did you get too seasick in that last gale, and decide to turn a landsman?"

The scene was Paddington Station. At the bookstall a young lad had been buying a paper, when he had heard himself addressed as above, and had felt a light touch on his arm.

He was a good-looking youngster, neither very dark nor very fair, and rather stout-built; somewhat, it may be said, of the sturdy, John Bull type of figure. His dark-blue suit, with its bright metal buttons, betokened the young, seafaring cadet. His keen, grey eyes, as he turned them towards the one who had addressed him, were frank and honest-looking.

He saw, standing looking at him, another lad about his own age, and dressed in a suit almost identical with his own. A fair, curly-headed, rather slim youngster, with, he thought, the merriest, most roguish-looking blue eyes he had ever seen.

"I—er—beg your pardon," he said, "but were you speaking to me? Did you say Branson? That's not my name—"

"Eh? Not your name? Oh, I'm sorry! I can see you're not Branson now I've got a better look at you. But you're uncommonly like—like, well, like one of our crowd!"

"That's all right. No harm done," was the answer given with a good-humored nod. "Are you one of the Dolphin chaps?"

"Hit it first time, sonny," returned the other, with an air of easy-going nonchalance. "I'm a Dolphin boy, right enough; name, Wilfrid Caryll, commonly known as Will Caryll for short; sometimes—about December in each year—called Christmas Caryll, by cheeky kids who think they've hit upon something new. But you, sonny? If you're not Branson—and I can see now you're not—you're a bit darker—who are you? Where d'ye hail from, and where are ye bound for?"

The first lad smiled at the stranger's jaunty, free-and-easy manner.

"My name's Jack Kendall," he said, "and I'm on my way to join the Dolphin too. Perhaps if I tell you that I have a cousin—Clement Branson—already there, it may explain what's puzzling you."

Caryll whistled.

"Oh, that's the explanation! Of course I know Clem Branson; but, I say"—here the speaker paused—"if you're a new boy, and Branson your cousin, I s'pose he knew you were coming; so why didn't he tell us? Never a word has he said about it, so far as I've heard."

Kendall flushed, and looked embarrassed; but ere he could reply another voice—a man's voice this time—broke in:

"What, Branson? I did not know you were up here!"

Kendall swung round, and found himself face to face with a tall, fine-looking, elderly gentleman, who was standing regarding him with a perplexed frown.

Young Caryll stepped towards him and explained:

"It's not Branson, dad. I've just made the same mistake. This is a new boy, who's on his way to join us."

"H'm!" said the stranger. "I see, I see. Yes, of course; I see now. But, bless me, how like young Branson! At first I really I bought—humph! Strange, very strange!"

Muttering thus, more to himself than to either of the two, the stranger continued to look at the lad with such a keen, penetrating gaze as to add greatly to the latter's embarrassment.

Seeing this, young Caryll took it upon himself to formally introduce the two:

"His name's Jack Kendall, dad." Then to Jack: "This is my father, Sir Keith Caryll."

Sir Keith still, for a few moments, gazed at the youngster with a glance that seemed to scrutinise every detail of his face. Then, suddenly rousing himself, as it were, he murmured with an air of increased interest:

"Kendall—Jack Kendall! Yes, it must be so! I can trace the same likeness; but this lad must be like his mother. Tell me, my lad, are you, then, the son of John Kendall, who, I heard, died a few months ago?"

"Yes, sir," Jack returned quietly, a shade passing over his face at the reminder.

"Ah! I thought so. I was sure of it. And your mother, lad? I used to know her—er—years ago. Is she well?"

Sir Keith seemed to wait anxiously for the answer. It was as though he feared to hear she was dead too.

"My mother is well, sir, thank you," said Jack. "She is over there. She has come to see me off."

"Good, good!" said Sir Keith. He turned, and, looking across the platform in the direction indicated, saw a lady, attired in deep mourning and widow's weeds, standing beside the waiting train.

"I'll—why, yes, I'll go and speak to her!" exclaimed Sir Keith, and went off towards her.

Young Caryll turned to Kendall:

"It seems my dad knows your people," he said, as though that fact properly clinched matters; "so you and I ought to be friends, I guess. Where's your kit?"

"Over there," Jack was going to say, "by that third-class carriage," but he hesitated.

"You'd better bring it along and get in with us. There are several of us going down together. I'll introduce you. You can see 'em waiting yonder. Come on!"

Kendall, glancing across the platform, saw a knot of lads in cadet uniform grouped round a carriage door. And again he hesitated, and his face once more flushed, for it was as he had been fearing. They were going first class, while he knew that the ticket his mother had taken for him was third class.

He was conscious, indeed, of something more than a passing flush; he felt himself go hot and cold all over.

This was another of the unpleasant "rubs" to his pride he had been receiving at intervals ever since his father had died and left his mother practically penniless. Before that time he had been used to riding first class and to similar little luxuries, like these other lads. But since then he had known what the "pinch of poverty" meant.

Jack Kendall's position was certainly at this time, a trying one. He was being sent to join the Dolphin at the expense of a very wealthy, but eccentric, old bachelor uncle, Mr. Robert Kendall, the brother of Jack's late father. In response to an appeal for assistance, made by Mrs. Kendall, that gentleman had agreed to pay the cost of sending him to join the Dolphin training-ship, to undergo a preliminary training, on probation, as it were. If his conduct were satisfactory, and he succeeded in passing the necessary "exams," then Mr. Kendall might be disposed to help him still further. That was all he would promise; and as this assistance had seemed to be given grudgingly, and without any display of either affection or interest, Jack felt sorely that he was little better than a pauper, living on a relation's charity. Mrs. Kendall, however, had been only too glad to accept the offer—indeed, her circumstances had left her no alternative.

It is not to be wondered at, then, that Jack flushed up and felt uncomfortable when his new friend said "come in with us." Presumably, all these youngsters, his future shipmates, were the sons of more or less wealthy people, able to send them down first class and supply them with plenty of pocket-money. But Jack's uncle had omitted pocket-money from his list of the expenses he was willing to defray, and had even shown himself almost miserly over the lad's outfit. What then, Jack asked himself bitterly, was his position likely to be amongst these other lads?

Then, suddenly, his thoughts took another and a higher turn. The recollection of the sacrifices he knew his mother had made for him, in adding various articles to his outfit alone—not to mention a hundred other ways—rose up in reproof. Should all the sacrifice, all the quiet heroism under adversity, fall to her? Should he be mean enough, cowardly enough, to wish to shirk his share?

This question no sooner presented itself thus in the lad's mind than his better nature answered it. There was, after all, no shame in honest poverty, and he was not going to show himself ashamed of it.

He drew himself up, squared his shoulders, and stepped out briskly beside his new acquaintance, his head in the air, ready to bear his part honestly and fearlessly whatever might betide.

"Here you are, sonnies!" cried Caryll, as the two marched up to the waiting group. "Here's someone else to join our party! Captured him over by the bookstall, and brought him along, all alive O! Now, a penknife to a bath-bun, you can't tell me his name first go off! Now, then, be quick! Hurry up, look sharp! Shout it out!"

"Why, it's Branson, of course," three or four shrill young voices called out.

"Ah, then it isn't! Thought I'd have you there! Caught you nicely! This is a new boy, sonnies; name, Jack Kendall; profession, rank, or calling, Clem Branson's cousin!"

At this announcement there were cries of surprise. One or two looked indignant, and seemed to think they had been unfairly "had." But they clustered round to inspect the new arrival, and some shook hands cordially, while others preferred to be noncommittal, as it were, and to hold themselves in reserve.

Nearly all the lads were about Jack's own age. The two exceptions were Will Caryll's brother Bruce and a friend who was with him. To this brother Will whispered something, and he then came forward in a patronising way, and good-naturedly extended to the new arrival the favour of a friendly greeting. As he was the oldest boy there, the fact had a distinctly favourable effect upon the others; and Jack was soon chatting away busily, answering questions and putting queries in his turn.

In the midst of this Will Caryll said suddenly:

"Hullo! Dad's beckoning. Wants you too, Bruce, I think."

So saying, he slipped his arm into Jack's and marched him off, his brother following in their wake. As they drew near to Sir Keith he motioned to his sons to come forward.

"Come, hurry up, you two! I want to introduce you to this lady. Here they are, Mrs. Kendall! Here are the two young budding Nelsons! The other one—Trevor—is at Osborne. Went back there yesterday."

Mrs. Kendall received them with a gracious kindliness that put them thoroughly at their ease. It was easy to see that she must have been at one time a most beautiful and attractive woman. And even to-day, though her face bore the marks of recent grief and distress, she exhibited a winning, lovable nature which attracted the two lads and won their hearts at once.

They had no mother of their own—for Sir Keith was a widower—and perhaps that was one reason why they appreciated the kindly, motherly way in which she greeted them and began chatting with them.

Sir Keith, meanwhile, led Jack away with him. He took him to the booking-office, where he exchanged his third-class ticket—which he must have obtained from Mrs. Kendall—for a first-class one. This he gave him, at the same time slipping two half-sovereigns into his hand.

"Tut, tut! There, there!" he muttered, as Jack essayed to thank him. "I'm a very old friend of your mother's, my lad. Knew her years ago; and I'm taking an old friend's privilege. You can't do without pocket-money, my lad, and I fear your mother can't allow you much now."

Jack felt a lump in his throat, and his eyes grew moist, as much at the kindliness of the words and tone as at the little load of worry that had been lifted from his mind. And it was all so unexpected! It was little enough he had experienced in the way of kindness from either friends or strangers since his father's death!

Want more pocket-money! Yes, he knew he would; for, as Sir Keith had shrewdly guessed, it was little enough his mother had been able to give him. He could foresee what his position was likely to be amongst these other lads, who were sure to be well supplied. Still, he could do with less than a sovereign. Ten shillings more would be enough; it would indeed be wealth compared with what he had expected to carry down with him, and the other ten shillings his mother wanted more than he did. Therefore—

But at this point Jack's thoughts were interrupted by the necessity for hastening back to the train. It was nearly time it started, and the guard was looking about and hurrying up the porters.

There were hasty good-byes, Jack was folded in his mother's arms in a last long embrace, doors were slammed, whistles sounded, and the train moved off.

On the platform, amongst other groups, stood Mrs. Kendall and Sir Keith, watching a number of caps dodging about outside a carriage window like a swarm of gigantic bluebottles, and listening to a chorus of shrill cheers from lusty young throats, gradually dying away as the train receded.

Thus was young Jack Kendall launched upon his seafaring career under more promising conditions than but a few minutes before had seemed to him likely or possible.

It was characteristic of him that even during the hurry of leave-taking he had managed to slip into his mother's purse one of the two half-sovereigns.

THE compartment in which Jack Kendall found himself was uncomfortably crowded. Boys were squeezing one another on the cushions, with others perched on the arms between, and still there was an overplus of youngsters who had to manage as best they could.

If these latter could have found sitting accommodation on the racks above they would doubtless have cheerfully climbed up there. That, however, not being feasible, they had to stand.

The party had, much to their surprise and displeasure, one strange fellow-traveller. He was an old gentleman, with grey hair and whiskers, who had rushed in—had almost been tossed in, in fact, at the last moment, as the train was on the move.

He had subsided into the corner by the door, and there remained, getting his breath, while the youngsters crowded round and nearly deafened him with their shrill cheers, and half- smothered him as they pressed to the window to look out and wave their caps.

When they had finished their cheering, and the excitement of starting had died down, the old gentleman, on the one side, and the lads on the other, mutually "took stock" of each other.

The lads were inclined to resent the stranger's intrusion, and many furtive glances and nudges were exchanged amongst them. He, however, appeared unconscious of anything amiss, and beamed upon them benevolently through his gold-rimmed spectacles.

"Aha!" he murmured. "Young sailors, I see! Returning to your ship, I suppose, eh?"

He addressed himself more particularly to Will Caryll, that young gentleman having, after a fierce but short tussle with two of his shipmates, secured the corner opposite.

Now, it was one of young Caryll's natural gifts that he could, when he so willed it, summon up a smile that was almost seraphic in its sweet, babyish innocence. The present seemed to him a suitable occasion for such a display; and thus it was that he and the old gentleman beamed mutually upon one another.

"Yes, sir," said Will—and his tone was as respectful as his manner was engaging—"I am piloting these young sailors back after our Easter holidays. I am afraid they must have annoyed you with their noise, sir. I will try to keep them quieter the rest of the journey."

"Oh, never mind, never mind! And what ship do you belong to?"

"The Dolphin training-ship, sir, at Wincombe."

"Oh, the Dolphin! Let me see, I've heard of her. She's Captain Probyn's ship is she not?"

"Yes, sir. Do you know him, sir?"

The other shook his head. "No; I've never met him; but I've heard of him. He trains young gentlemen, I believe, for both the Navy and the merchant service."

"Quite right, sir, Navy first; then, if you fail to pass the examinations for a naval cadet, you can stay on and train for the other."

The old gentleman nodded. "And how do you like the life there?" he asked next. "What sort of a man is Captain Probyn?"

"Well, sir, I hardly like to say. He knows his work well—he's a thorough good seaman and all that, but he's a bit crotchety in some things."

"Ah! You think he knows his work well. That's good, very good indeed," returned the stranger, evidently amused. "But crotchety, eh? In what way, now, is he crotchety?"

"Well, sir, he has his crochets about the simple life and all that. Thinks we ought to be taught to look after ourselves and pick up our own living, as it were. So we have rather a queer life of it at times. For one thing, we have to live on what we can catch."

"Live on what you can catch!" exclaimed the old gentleman, greatly amazed. "How do you mean?"

Before replying to this query Will glanced round at his shipmates. These were domestic secrets, and he seemed to be mutely inquiring of them whether it would be right to reveal them to a mere stranger.

Jack Kendall was listening with great interest, anxious to learn all he possibly could as to what his life on board the Dolphin would be like. He felt much impressed by Will's manner, and he particularly noted the serious expression in his eyes, from which the look of laughing, lurking mischief had completely disappeared. Not a trace of it remained; it had fled, as though for ever.

Will seemed satisfied with what he read in the faces of his friends, and turned his quiet gaze once more from them to his questioner.

"Well sir," he said slowly, "we don't want it to be talked about, but the fact is we have to fish for ourselves. And it takes all our time, I can assure you, sir, to pick up a living for two or three hundred boys with lines over the ship's sides, catching small crabs, and starfish, and jelly-fish—"

"Eh? Starfish? Jelly-fish?" exclaimed the listener. "Surely you don't eat jelly-fish?" And he looked round at the others as though in doubt.

"We're allowed shrimp sauce with it, sir," said Will's particular chum, a lad named Boulter. "That is, when we can catch the shrimps."

"Good gracious!" the stranger ejaculated. "What a strange diet to be sure!"

"We're half starved on it most of the week," another "budding Nelson," named Steele, feelingly asserted, "unless we manage to get some eels for pies."

"Oh, yes, we're all right then," Will agreed. "That is, if we can contribute some jam amongst us. Eel-and-jam pie is awfully nice, sir," he added, looking at the old gentleman with his open- eyed gaze, and without so much as the flicker of an eyelid. "Did you ever try eel-and-jam pie, sir?"

His auditor looked aghast. He evidently scarcely knew whether to believe these surprising statements or not. But as he glanced wonderingly at the faces around, they looked back at him with an air of such conscious rectitude that he scarcely liked to hint disbelief.

"But—er—there are other fish—whiting, soles, and so on—to be caught, I suppose, eh?" he suggested.

"Oh, yes, sir," returned Will, with something like a sigh; "but you see, they don't come swarming round the ship in the river. We have to go after them in boats out to sea, beyond the mouth of the river. We are allowed to do that on a Saturday—that is our holiday—so as to get a catch for our Sunday dinner."

"Then there is the cooking," a boy named Egerton reminded Will.

"Ah, yes," murmured that young gentleman, shaking his head. "Captain thinks we ought to learn to cook, so we have to do the cooking in turn. And—perhaps you'll scarcely believe it, sir—but some of the chaps don't know how to cook any more than—than—well, than you might yourself, sir! At any rate, they often send up the grub half-raw."

"Dear, dear, dear!" said the old gentleman. "And yet," he continued, with a gleam of humour in his eye, "you seem to do pretty well on it. You don't look starved, you know."

Will gave another sigh, and shook his head again sadly.

"We've been on holiday, you see, sir," he explained. "We've had three weeks' feeding up at home. You should have seen us when we left the Dolphin!"

"But—you're not all Dolphin boys, I see," said the traveller, looking across at Bruce Caryll and his friend, and eyeing the badges they wore. These two had appropriated to themselves the two corner seats beside the further door, by virtue of their superior age and rank.

So far, neither had said anything. They had merely looked on and gravely nodded their heads here and there.

"That's my brother and his chum, sir," Will volunteered. "They're not going with us all the way; they will have to branch off presently for Dartmouth. They are full-blown Naval cadets there, where—you know, sir," and he leaned over and whispered, as though afraid to speak the words above his breath, "where—er—the—er—you—"

The old gentleman nodded knowingly, and seemed to be trying to look as wise as Will himself.

"I know, I know—I understand," he returned. Then to Bruce and his friend: "And how do you fare, my lads?"

"Oh," said Bruce, with a lordly air, "We are treated very differently, sir. They treat us like gentlemen. They wouldn't dare do otherwise, we have so many young swells amongst us—sons of some of the highest people in the land."

"Quite so. And what sort of diet do they give you young swells?"

"Well, sir, the grub's all right—nothing to complain of on that score—plenty of salmon and cucumber, and chicken, game in season, and all that."

How long these remarkable accounts of the way the young sailors were treated would have continued, or how far they might have allowed their fertile imaginations to carry them, it is difficult to say. It so happened, however, that an interruption occurred. The engine gave a series of warning whistles, the brake was applied, and finally the train came to a stop.

One or two of the lads thrust their heads out of the window. They saw the guard coming along to meet the station-master from a small station a little way ahead. Judging from this that the stoppage was likely to be more than a brief one, they promptly opened the carriage door and swarmed out on to the line. By the time the guard had come up Will Caryll and two or three more had scrambled on to the roof of the carriage, in order, as they said, to see what the trouble was.

Needless to say, their fellow-traveller was greatly perturbed at this, and mildly, but vainly, expostulated.

"Now then, young gents, come down, come down!" growled the guard as he drew near. "Get back at once—we're goin' on."

"There's no hurry, Bruce," said Will coolly from the roof, "There are some sleepers on the line in front, and the guard's going to wake 'em up before we can go on."

"I don't want none o' your chaff!" snapped the guard irritably. It was easy to see he was put out by the stoppage, and was in no humour for joking.

"You should say raillery—not chaff, guard," smiled Will. "Every well-informed railwayman ought to know that."

"Come down, young gentlemen," pleaded the stationmaster, "What you're doing is against the byelaws."

"Looks as if we'll have to make our beds here and pass the night," grumbled one of the passengers, looking out from the next window. He was evidently getting impatient at the delay.

"Couldn't do that, I guess, sir," Will put in slily. "It would be against their by-by-laws."

The passenger laughed, but the stationmaster frowned; and a man with him, who had the appearance of an engine-driver, muttered something angry under his breath.

"Who's that, I wonder?" asked Boulter.

"Only an uncivil engineer," said Will as he climbed down, followed by the others. They had seen signs of a start.

As a matter of fact, they were only just in time, for they had scarcely crowded in before the train was on the move.

"Ah, you were almost left behind, you see," said the old gentleman, with a grave shake of the head. "It was very foolish of you to get out and climb on the roof. Might have turned out dangerous too. Why did you do it?"

"Force of habit, sir," returned Will serenely. "You see, on board ship we're accustomed to climb the mast to get a good look- out. They don't have masts on trains, and the engine-funnel was too far away, so we had to do the best we could."

"If I'd been as venturesome as you," remarked the old gentleman, "I would have liked to take advantage of that stoppage to change into my own carriage where I left my things. I could not find it at the last moment at starting, and that's why I got in here. However, I do not regret it, since it has enabled me to pick up from you boys some—er—most interesting information."

But he seemed to have obtained all the information he wanted for the time being, for he asked no more questions, but buried himself in his newspaper till the train stopped at Swindon. Then he quitted the compartment and went in search of his own.

Then the Dolphin young gentlemen turned their attention to the "new boy," and supplied Jack with a further stock of particulars and details relating to their life on board the Dolphin, of an even more extraordinary character than that he had already listened to.

The two Dartmouth cadets, in their turn, not to be outdone, treated him to some startling yarns of the doings of themselves and some of their highly aristocratic associates. These included stories of pranks in which names were casually mentioned which almost took Jack's breath away, and to which he listened in wondering awe. It is hardly surprising that before they reached their journey's end he was in a state of hopeless bewilderment, not knowing what to believe or what to disbelieve.

There was one point, however, upon which he gained some useful information. He learned that Sir Keith Caryll had himself been in the Navy, from which he had retired just before coming into his present title and an extensive estate.

His residence, Coombe Hall, Will told him, was situated near the coast, between Dartmouth and Wincombe.

"So you see," said Will, "both Bruce and myself are within easy reach of our home, and we are each allowed to go there sometimes on a half-holiday. And dad's always pleased to see any of our chums. Bruce brings over some of his young swell friends sometimes, and I can take anyone I chose. So you will be able to come too."

"I should be very pleased," said Jack, hesitatingly. "But—"

"Oh, we can't have any 'buts,'" laughed Will. "And there's another thing—our motor-launch will be at the landing-place to-day to take me and my friends off to the Dolphin, and we can take you as well. That will save you from being fleeced by those old sharks of boatmen, who are always on the lookout for new boys who don't know the ropes."

Jack began to express his thanks for this welcome offer, when his new friend once more interrupted him.

"Oh, but I forgot. Perhaps you are expecting your cousin Branson to meet you and take you in tow?"

Again, at the mention of his cousin's name, Jack flushed. But he only shook his head.

"Oh, well," Will went on, "that idea occurred to me because I noticed—H'm! I hardly know how to explain, but, you know, I expect, that Branson has been passing his holiday on board his father's yacht? That is your uncle's yacht, I suppose?"

"Yes. Mr. Branson is what they call an uncle by marriage."

"Well, they've been at Wincombe, cruising about there, and—funny thing!—I happened to notice a man who is, I know, one of the yacht's crew, at Paddington Station. And he seemed to be watching you."

"Watching me?" exclaimed Jack, astonished. "What should he want to watch me for?"

"Don't know. Struck me he might have some message from your cousin to give you; and when he saw you with a crowd, hung back till he had a chance to get you alone."

"No," replied Jack, with decision; "you must have been mistaken, I think."

Just then the train began to slacken speed, and no more was said. They were approaching the junction for Dartmouth, and Bruce and his companions began collecting their property.

At the junction the two got out and joined a number of fellow- cadets who had travelled in other parts of the train.

Then, amid fresh volleys of cheers, the train moved on again, and a short time afterwards it deposited the Dolphin lads at their destination—Wincombe Station.

"MY word!" exclaimed Will Caryll as he and his little crowd marched from the station towards the landing-place on the river-bank. "Here's a pretty go! A sea-fog! We shall have trouble, I'm thinking, in finding our way to the ship."

All the way down till a little while ago the weather had been bright and sunny. Then the wind had changed, the sky had become overcast, and it had grown colder, and now they could see that a driving mist was coming in from the sea.

It came swirling up the river, blotting out the landscape, and hiding not only the further side, but all the craft upon the water.

As they trudged along, all pretty well loaded with their belongings. Will grumblingly expressed surprise that his father's servant had not been at the station to meet him.

"But look here, Kendall," he said aside to Jack, "I saw another chap at the station from your uncle's yacht, and it struck me again that he was looking for you. Yet he didn't speak. Seemed to me, too, that he followed us down, though I don't see him now."

"I am sure you must be mistaken, Caryll," Jack assured him. "If you must know, I may as well tell you now in confidence that—well, my uncle, Mr. Branson, is not very friendly with my mother. So neither he nor Clement is likely to trouble about me."

Caryll whistled softly.

"Oh, I see. Sorry I spoke. That, I suppose, then, accounts for Clem Branson saying nothing about your coming, and not being here to meet you?"

"Yes; that's all there is to be said," Jack answered quietly. "And now, don't let's talk any more about it."

He could not tell this new friend how matters really stood, how badly he and his mother had been treated by these same relatives since his father had died. He could not tell him yet, at any rate. But the thought of it brought a flush to his face and an indignant light to his eyes, which his observant companion noticed, and from which he, no doubt, drew his own conclusions.

"Righto!" said Will cheerily. "But it makes it seem all the more funny seeing those two chaps from their yacht, one up in London and one down here, as if they were watching for you."

"I tell you you must have been mistaken," Jack declared again. "If not—well, it must just have been a curious chance, a coincidence."

Upon the landing-place, when they reached it, there was quite a crowd of lads standing, cold and shivering. Some were looking for boats they had expected to be ready for them, others were bargaining with boatmen to take them off; and the boatmen, on their side, were taking advantage of the fog to try to get extravagant prices for the work.

"Never mind those chaps," said Will to Jack; "you stick to me, and I'll get you aboard ail right. Crimmins, there's that fellow again that I saw at the station!"

Jack looked round, but the man had already moved away.

Will walked on towards one end of the quay, followed by Jack and four or five others. There, moored to the side, they found a roomy, well-fitted, comfortable looking motor-boat, with the name Comet painted upon her bows.

Beside her stood a big, powerfully-built man, seemingly half sailor, half manservant, who came forward as he caught sight of Will to relieve him of what he was carrying. His hair and beard were red, turning to grey, and it was soon made clear by his speech that he hailed from "Ould Oireland."

He was evidently well known to Will's chums, for he received a chorus of friendly greetings from them, some being playfully couched in an imitation of his own brogue.

Jack noticed amongst other details that he had a fresh red weal across his nose as though he had but recently been in the wars somewhere.

"Hallo, Dennis," said Will, as he handed over his little load, "where have ye been loitering? I thought ye'd have been at the station to meet us, and—Why, man, what's the matter with your nose?"

"Sure," put in Boulter, "he's been promoted, only they've put the stripe on his nose instead of his arm!"

"Oi've had throuble here, Masther Will," said Dennis. "Oi did start fur the station, but whin a fog came on Oi turned back t' look t' the cushions, an' Oi found two spalpeens aboard. It's makin' free wi' the boat they wor."

"Making free with the boat!" exclaimed Will, astonished. "What for? Who were they?"

"Faith an' it's meself as can't tell ye that same, sorr. Thavin' rascals, I guess lookin' fur phwat they could pick up. Annyways, Oi hustled thim out pretty quick; but in the scrimmage Oi slipped, and banged me face on the rail. An' thin they sloped off in the fog. So Oi didn't lave the boat agin."

"Oh, Dennis, Dennis!" sighed Steele. "Fahncy it's foightin' ye've been! An' ye niver let us knowt' give us a chance to join in! Whin ye've stowed that cargo, sthand by an' look out for more. We've plenty here amongst us."

"But two men on board our boat!" said Will, in a puzzled tone. "Do you know them at all? Ever seen 'em before, Dennis?"

"Sure it's strangers they wor, Masther Will. Oi never see 'em before; but Oi'd know 'em again annywheer. Low-down, sneakin'- look-in' pirates they wor."

Amidst a general chorus of ejaculations and many guesses, all more or less vague and some very wild, the youngsters stowed themselves and their belongings on board, and the boat moved slowly oat into the fog.

It was necessary to go cautiously, for there were evidently a good many craft about. They could be heard, but not seen. The swing of oars in the rowlocks came from several directions at once, and the whoop of a siren told that a steamer or tugboat was somewhere on the move.

And amongst the other sounds there could now be heard the "jug, jug" of a steam launch quite close at hand.

Dennis, however, knew his way, for he went on steadily, and without hesitation. But he turned his head more than once, and glanced inquiringly in the direction of the sound made by the launch.

"Sure it's follerin' us she seems t' be," he muttered at last. "It's runnin' into us they'll be if they don't care."

"It sounded to me as if they started when we did, or a little after," said Will. "Was there a launch alongside the landing- place, Dennis? I didn't see one."

"Niver a bit av wan, sorr, as far as Oi saw. But it's follerin' us she seems t' be."

"Hallo!" cried Boulter suddenly. "Why Will, your boat must be leaking badly—the water's coming in!"

"Eh, what? Our boat doesn't leak!" Will declared.

"She does—she must! The water's coming in," exclaimed first one and then another.

Jack, who was farther forward than the rest, pulled up a loose flooring-board and put his hand down.

"Why," he called out, "there must be a hole here! The plug's got out."

"There ain't no plug, nor no hole theer," said Dennis.

Dennis stopped the motor and left the helm, and, snatching up a piece of oiling rag, went forward to investigate.

"Sure, an' ye're roight, sorr!" he exclaimed; and he stooped down and began stuffing his rag into the hole under the water.

Will and other lads crowded forward, too, in wondering excitement.

Then from out the mist the launch they had heard suddenly appeared—a boat far larger and heavier than the Comet.

Jack and Caryll were amidships, the latter stooping over Dennis, when Jack, glancing round, saw the sharp prow of the launch coming straight at him.

With a quick cry of warning he sprang forward, making a grab at Will as he went in a gallant endeavour to drag him with him.

But his hold slipped as Caryll, warned by the cry, started to his feet, standing up almost in the very place from which Jack had jumped. He, too, saw the oncoming prow of the launch, and instinctively put up his hands as though to fend her off. The next moment she struck him with terrible force as she crashed into the side of the boat, and sent him flying overboard.

Jack saw Will fall like a log, and guessed that he must have been stunned by the blow. And at once, without a second's hesitation, he sprang after him into the swirling waters.

JACK KENDALL was a splendid swimmer and a clever diver, and it was well for him that it was so. For when he came up, after grasping the unconscious form of Will Caryll, he found himself underneath the steam launch which had run into them.

He had therefore to dive again and swim a short distance under water ere he could come to the surface to breathe—a feat which, encumbered as he was, none but a first-class swimmer could have accomplished.

When, finally, his head rose for a moment above the water, and he was able to draw a gasping breath, he felt almost too exhausted to support the dead weight of the unconscious lad he had brought up, and began to fear he would let go his hold.

Fortunately, however, another one was swimming close at hand. This was Will's chum Boulter, who had witnessed what had happened, and had jumped in specially to lend his aid.

He saw Jack come up with his burden, and swam towards him at once. A few quick strokes brought him to his side.

At the same moment something fell with a splash in the water beside them. It was a lifebelt flung by Dennis, and it had a line attached to it.

There ensued a babel of shouts, as those in the motor-boat called out to the two swimmers, advising them to do this and warning them not to do the other.

Jack and Boulter, however, managed between them, and aided by the lifebelt, to hold up their still unconscious friend the while that those in the boat hauled on the line, and so gradually drew them to her side.

Then Will was lifted on board, and his two plucky rescuers scrambled in after him.

"It's gettin' his breath he is—Heaven be praised!" Jack heard Dennis say a little later. It was his way of announcing that Will was coming to, and very glad and thankful the others were to hear his words.

Reassured in that direction, they began to look round to see what damage the boat had sustained, and ascertain who it was that had done the mischief.

"Whoy—they've sheered off—the blunderin', murtherin' vagabones!" exclaimed Dennis in tones of indignant disgust. "Phwat dirty spalpeens!"

Jack stared round in amaze. True enough, however, was it that the launch had backed away, and had completely disappeared in the fog. The people on board, whoever they were, had been mean enough, callous enough, to take advantage of the preoccupation of those they had so nearly run down to make their own escape.

They had not even stayed to ascertain what harm they had done, or whether anyone had been drowned. And, of course,—as Boulter put it—they had left no card giving their name and address.

"But who could they be?" said Jack. "What was her name?" queried another. "What were the people like on board?" asked a third.

Strange as it seemed, no reply was forthcoming to these questions or to the many others which they now hurriedly asked of one another. They had all been too excited and anxious, and too much taken up in watching for Jack and Caryll, to take much notice just then of the launch.

"An' faith. Oi didn't see anny av the galoots at all at all," Dennis declared. "An' I belaves they wor all too mane t' show theirselves."

This seemed, in fact, to be the general opinion. And as the launch had been decked forward—they all agreed upon that point, which was about all they could positively remember—whoever was on board must have intentionally remained hidden behind it.

Two there were—Jack and Boulter—who had a confused recollection of having seen a figure leaning over the aft part of the launch; but they had been naturally too intent on their work of rescue to pay particular attention to the fact just then.

So her identity and that of the people in her was a mystery, and seemed likely to remain one.

Caryll was now able to sit up and talk, and Dennis finished plugging the hole in the bottom of the boat. Fortunately he had already stopped it temporarily before the collision had taken place.

Then, as no great damage had been done to the side of the boat, he started the motor, and set off once more to find the Dolphin.

This he managed to do within a short time, the three lads who had been overboard sitting, meanwhile, covered up under a pile of rugs and wraps he had fished out.

Then, through the mist, there loomed out a vast form which, as they drew nearer, resolved itself into a huge, wooden three- decker, "one of the olden time." The white portholes showed up on the high, dark side of the old man-o'-war, while overhead there towered the great masts, strong and heavy-looking yet graceful amid a maze of ropes and cordage and pulleys, through which the wind whistled and moaned.

Suddenly, from the upper deck, there came a sharp challenge, uttered in a shrill young voice:

"Boat ahoy, there! Who are you?"

"That's Evans," said Boulter to Jack, while Caryll sang out an answer to the challenge. "I know his voice. He's one of our set. Won't he be surprised when he hears we have been overboard?"

The boat was brought round under the quarter, where there was an accommodation ladder, and the youngsters quickly swarmed up it, followed by Dennis, carrying some of their things.

They were received on deck by a small crowd of boys and a petty officer, who had come forward on hearing the challenge, and who gravely inspected the luggage, including Jack's outfit, before allowing it to pass.

There was a buzz of talk amongst the knot of lads when it was seen that some of the newcomers were wet through.

"Lost their boat in the fog and had to swim aboard, I guess," said one.

"Had too much lemonade before starting, and fell into the water. Shocking!" commented another.

"It's Caryll," said a third. "I suppose that antiquated motor- boat has come to grief at last. I always said it would. Petrol took fire, I expect, and they had to jump overboard and get half- drowned to save 'em from being burnt alive."

Meantime Dennis had explained matters briefly to the petty officer who, turning to the three, ordered them to go below and change into dry clothes, while he conducted Dennis himself to the officer on duty, to report more fully what had occurred.

Such was the manner of Jack Kendall's arrival on board the training-ship—an arrival as unusual and noteworthy in its way, as some of his after adventures proved to be.

CARYLL led Jack, by devious ways and complicated passages, to a spacious apartment on a lower deck. The long rows of neatly folded hammocks proclaimed it to be a dormitory.

"By good fortune," said Will, "this hammock next to mine happens to be vacant. I spoke to Joyce—he's the petty officer you saw—and he said you could take it for the present. I don't know if you'll be able to keep to it, but I will have a try to get it for you. Boulter's is on the other side of mine."

This was good news, and Jack murmured his thanks. He would be berthed in the company of someone he knew to start with, at any rate.

"Here's your kit coming," Will added, as he opened his own chest and began hunting for fresh clothes.

Jack glanced round, and saw a long, lanky youth approaching, bearing his sea-chest, which he put down, and then stood and looked at the three with a set grin on his freckled face. This youth was one of the servant staff, and his name was Simmons, wherefore, and on account of his habit of grinning, the cadets had dubbed him "Smiling Simon." His present grin, therefore, was no product of the moment; it was always there. Indeed, it was a settled article of belief amongst the lads that it had been stamped on Simmonds in his infancy, and so firmly that it had never since come off, even for an hour or two.

"Clothes seems t' fit a bit tight, gen'l'men," he giggled. "Ye looks as if ye might be wet. Did ye swim 'ere?"

Then he noticed Jack more particularly.

"I'm bothered if 'ere ain't another Mr. Branson!" he exclaimed.

"You keep your remarks till they're asked for, Smiling Simon, and hook it," said Boulter. "You're not wanted here. Now, will you go, or will you wait till something comes sailing in a bee line for your head?"

Simon went off, still grinning, as though vastly amused; but he did not venture on any further comments.

"He gives me the worries, that chap," Boulter complained. "He always seems to be laughing at you. He's a regular Cheshire cat! Why, here he comes back again—oh! H'm! Yes! You can set that down."

Simon had returned bearing a tray with three cups of steaming hot cocoa, which Petty-officer Joyce had sent down to help warm up the shivering lads.

They seized on them gladly, and Boulter, who was always ready to appreciate anything in the eating or drinking line, even condescended to nod approval at the bearer.

"If it wasn't for your mouth, Smiling Simon," he said, "I might get to like you in time,—especially if you could bring me another cupful where this came from. Oh, don't!" he exclaimed, as Simon's smile seemed to grow broader than ever. "Try to whistle, man—try to whistle!"

Simon shook his head and went his way, and a few minutes later the three, having completed their change, finished their cocoa, and hung their wet clothes up to dry, marched up to report themselves to Mr. Melfort, the officer on duty.

He was really Lieutenant Melfort, for he had been in the Navy and had retired with that rank. But when he had joined Captain Probyn he had dropped the title, and was generally known as plain "Mr." He was still a fairly young man, with a fine, well-setup figure, a clean-shaven face and keen but withal kindly eyes.

"Come aboard, sir," said Caryll and Boulter, saluting; and Jack imitated them as well as he could.

Mr. Melfort glanced at Jack with evident interest, and Caryll introduced him.

"New boy, sir—Jack Kendall." Then to Jack's surprise and confusion, he continued: "Saved my life, sir. I should have been done for, I'm afraid, if it hadn't been for him."

It was the first reference Caryll had made to what Jack had done for him. So far, he had seemed to take it very much as a matter of course. But Caryll, who was always a quick observer, had divined exactly how Jack felt, and had guessed that it would only worry him to proffer his thanks. So he had bided his time, and brought the matter up now in his own way.

"Ay, ay, so I've been told," returned Mr. Melfort. "And I heard that you were both nearly drowned, for he came up with you under the launch which ran into you."

"That's true, sir," Boulter put in. "I can't think how he managed to hold Caryll up as he did. It was almost a miracle!"

"Y-y-you helped me—you know you did!" spluttered Jack, who now felt extremely uncomfortable, and wished they would talk about the weather, or the crops, or anything rather than the particular subject they had pitched upon. Mr. Melfort, looking at him with his keen, steady gaze, saw his embarrassment, and guessed the reason.

"Well, well," he said quietly, "you and Boulter both behaved pluckily, I was told, and very pleased I am to hear it. We ought all to feel thankful it ended as it did."

"It hasn't ended yet, sir," said Caryll. "I've got to tell my dad, and he will have something to say about it." And he glanced meaningly at Jack, who returned his glance reproachfully. He had just begun to feel easier, thinking the matter was going to be dropped. And now Caryll must not only keep harping on it himself, but threaten him with his dad in the future into the bargain! Jack looked for the moment almost as if he wished he had let Caryll drown, when, to his great relief, Mr. Melfort changed the talk to the steam launch.

"I must say I could scarcely credit what has been reported to me about the people who ran into you," he said. "I could not have believed anyone—anyone about here, at all events—would have gone off leaving the victims of their negligence to drown, as seems to have been the case here. We must have this matter looked into. I feel sure that Captain Probyn will make inquiries, and do all he can to find out who it was who was guilty of such a dastardly action."

Mr. Melfort did not often express himself so strongly as he did on this occasion, and it rather surprised the two who knew him. He, however, felt that the lives of these lads had been recklessly endangered by blundering navigators, who were too cowardly to face the consequences of their carelessness. And he was full of indignation and disgust at such conduct.

With Jack Kendall—at whom he shot one of his swift, penetrating glances—he felt particularly pleased. "A brave, modest, honest-looking youngster," he said to himself. "I shall take care that Captain Probyn hears how he has behaved. Unless I am mistaken he is a lad who will be a credit to us in the future."

He put a hand on Jack's shoulder.

"I'm pleased to welcome you to our ship, my boy," he said, "and hope you will get on well here. And you, Boulter"—laying another hand on him, "you too have done well to-day, and it will not be forgotten. I shall speak of you—of both of you—to Captain Probyn."

Boulter, it may be here said, was a little inclined to be fat—a consequence of his love of good living, which had already been hinted at. He often went, indeed, by the nickname of "Podge" amongst his fellows. But he was, all the same, a good- hearted, vivacious youngster, somewhat given to be hot-headed at times, but loyal and true when he once gave his friendship, and, as we have seen, by no means wanting in courage.

Caryll, seeing the mood Mr. Melfort was in, astutely put forward the request he wanted to make concerning Jack's place in the dormitory. And, greatly to Jack's delight, Mr. Melfort granted it at once. Then, with a few more words of kindness and encouragement, he dismissed them.

Caryll and Boulter went off to stow away some sundries they had brought aboard in their lockers, which were in an apartment adjoining the ward-room, and Jack started to go with them.

He felt in a particularly happy state of mind. The first day, to which he had looked forward with considerable misgivings, was turning out so entirely different from what he had feared it might be.

Where he had expected to meet strangers, and to be received perhaps with stand-off coolness, he had found only friends and cordiality; he had been welcomed and complimented by the chief officer; and last, but not altogether least, he had enough pocket-money to be able to feel himself on a fair equality amongst his fellows.

All, so far, had been plain sailing in smooth waters, and his spirits rose accordingly. He smiled to himself at his former fears, and congratulated himself on having tumbled amongst such a breezy, jolly, good-natured set of messmates.

But his innocent rejoicing was about to receive a rude shock.

As the three wended their way along the decks they came upon a group of lads who seemed to be engaged in a rather warm argument. Amongst them was Fred Steele, who had been one of Jack's companions in the train and the motor-boat.

Just when the three came up, Steele called out to Jack, and the latter heard him say:

"Here he is. You can ask him for yourselves."

Jack, with his ready good humour, went across to Steele, asking what he wanted. Boulter went with him, while Caryll passed on.

"I've been telling these fellows about our little adventure to-day," said Steele, "and they won't believe me. They think I'm yarning. I want you to tell 'em about it yourself."

Jack laughed lightly, and glanced round at the other boys. Then, all suddenly, he divined that here he was amongst a very different set from those he had previously met. Instead of cordiality and welcoming handshakes, he saw sneers and scowls, furtive glances of doubt and suspicion, impudent leers and mocking smiles.

He knew intuitively that he had made a mistake. He had blundered, or had been purposely entrapped, amongst a hostile crowd, though why they should show themselves hostile to a stranger he could not then understand.

The two who seemed to be the leaders of this coterie were—so he afterwards learned—named Dawney and Forder, and they were both older and bigger than himself. Dawney was a stout-built boy, with a hard, square jaw, and eyes that had at times a markedly cruel gleam in them. Forder, his intimate friend, had a loose, weedy figure, red hair, and appeared about equally blended.

Caryll and Boulter could have told Jack that both were notorious bullies, and also that they were Branson's particular cronies. But naturally they had felt diffident about warning him against the friends of his own cousin.

"Oh," said Dawney, "so you're Jack Kendall, the new boy, the young hero who goes about performing heroic feats!"

"We're going to be lectured about him by the captain, and sermonised by the chaplain, and have him held up to us as the virtuous model we all ought to bow down to and worship and copy, I suppose," sneered Forder.

Ere Jack could reply Steele struck in. He had called upon Jack in all good faith to confirm the account he had given of what had happened, and he was indignant at the way things were going. At the same time, he stood in awe of the two bullies, and dared not openly flout them.

"Nobody's said any such nonsense as that," Steele declared. "You said you didn't believe what I told you, and—"

"You shut up, you kid, or you'll get it hot!" Dawney warned him in a threatening tone. Then he turned his unwelcome attentions to Jack:

"Can you fight as well as swim?"

"Yes, I can," returned Jack quietly, "when there's good reason for it, but—"

"Bah! He's only a milksop, after all. I thought so," said Forder, with his usual sneer. "Pretends he can fight, but, of course, is too virtuous to do so."

"Try me!" said Jack warningly, advancing a pace nearer.

"All right!" returned Dawney, looking round at the other lads. "Fight one of these chaps."

"No; let him fight Boulter," was Forder's cynical suggestion.

"I shall do nothing of the kind!" Jack declared indignantly. "Boulter's done nothing to offend me. Why should I fight him?"

"Told you so. He's a coward, a boaster," said Forder.

"Let's take him at his own word," Dawney suggested. "We'll make Boulter do something to offend him, as he calls it—"

"No, you won't!" said Boulter stoutly. "I'm not going to—"

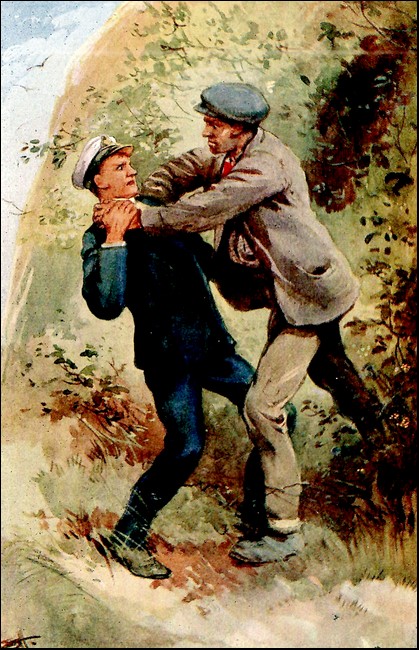

By way of answer to his defiance Dawney stepped across and struck the lad. It was a cruel, heavy blow, which sent him reeling against the bulwarks. Not content with that, the bully followed him up with the evident intention of hitting him again, when Jack sprang between them.

"Leave him alone!" he cried.

Dawney stared at him in amazement. The idea of a youngster daring to oppose a senior like himself seemed to him almost too funny for words. But it was a thing that had to be put down at once, and suitably punished later on.

"Get out of my way, you impudent fellow!" he growled. "I'll deal with you presently."

He took him by the collar and tried to throw him to one side, but Jack suddenly closed with him, and there was a fierce but very brief tussle. Then, all at once, Dawney gave a sharp cry of pain.

"He's going for me like a wild cat!" Dawney shouted almost in a scream. "He's biting me or something! I believe he'll break my arm! Pull him off, Forder; pull him off!"

This unexpected appeal caused a sensation amongst the lads around, and a murmur arose. They did not then know, of course, that Dawney's wild talk about "biting" was absolutely untrue. The simple fact was that Jack happened to have been taught something of ju-jitsu, and had merely practised upon the bully one of the commonest devices of the Japanese wrestler.

Now, just at that moment Captain Probyn himself came on the scene. He had just come on board, after being delayed by the fog, and was in a bad humour in consequence.

He had overheard Dawney's words without having witnessed what had gone before. He separated the combatants himself, and ordered them to follow him to his room at once.

On their way they passed Mr. Melfort, who merely looked curiously at them as he saluted his chief. Unfortunately for the luckless Jack, he was going ashore. He had already been kept waiting about by the captain's delay, and was now hurrying to keep an overdue appointment.

Hence, in Jack's interview with the captain, Dawney had it all his own way. Captain Probyn was a strict disciplinarian, and, according to Dawney's account, Jack seemed to have acted in a manner which, in a newly-arrived boy, seemed nothing less than an outrage.

A severe lecture followed, with the sequel that the unlucky Jack was mastheaded.

Petty-officer Joyce was summoned to see the order carried out, and under his directions Jack crept up the damp, slippery rigging, to pass his first evening on board in the cold, penetrating fog at the masthead.

WHILE the newly-joined cadet was shivering at the masthead in the fog, that same fog was doing him a service in another way.

It had been mentioned that the first officer, Mr. Melfort, had gone ashore to keep an appointment with a friend. But it turned out, when he reached the shore, very much after time, that the friend had grown tired of waiting and had gone away.

Thus Mr. Melfort had his trip for nothing, and instead of staying away all the evening, he returned within a short time to the ship.

There he heard of Jack Kendall's disgrace, and, feeling sure there must be some mystery connected with it, he set to work to make a few inquiries.

As a sequel, he sought out the captain, and laid the results before him. And he told him in addition, the story of the collision with the unknown steam-launch and Jack's plucky behaviour in connection with it.

"I do not believe," he declared, "that the lad I saw and conversed with, who seemed to me then so modest, almost shy, about what he had done, so honest and truthful in his appearance and speech, would go forth from my presence and behave in the manner Dawney led you to believe. And, indeed, I am satisfied now that he did not."

"But he made no defence," Captain Probyn pointed out. "He did not attempt to contradict a word of what Dawney said."

"Tut-tut! You forget the code of honour, the unwritten law, amongst boys against what they call 'sneaking.' Dawney, on his side, distinctly broke that law in accusing Kendall to you as he did; while, Kendall, in declining to defend himself, was only sticking sturdily to that same code under great temptation to throw it over. Really, I consider he would have been well justified, in the circumstances, if he had out with the truth. Evidently, however, he refused to lower himself to Dawney's level, and I must say I admire him for it."

Captain Probyn rose and began to pace thoughtfully up and down.

He was a tall, fine figure of a man. His dark hair and close- cropped beard were sprinkled with grey, but his bearing was that of a man in the prime of life, and his steady grey eyes were as bright and full of fire as those of many a younger man.

He was, as had been said, a stern disciplinarian, but he always strove to combine firm discipline with strict justice and impartiality. He and Melfort were staunch friends, and there was implicit confidence between them. Their friendship was indeed of such old standing that the conventional "sir" was generally dropped when they were alone.

"If your idea of the matter is the correct one, Melfort," he presently said, "I have done this lad a grave injustice, while over and above that I have been grossly deceived by Dawney. If that is really so, the wrong must be righted as quickly as possible. But it sounds a big 'if.'"

He continued to pace the cabin, his hands behind him, and a perplexed frown on his face.

It was a hard thing to have to confess himself in the wrong to a boy. But he was determined to be just if he were once convinced he had been misled.

"But how are we to get at the facts?" he went on. "You say that what you have told me was imparted to you under the seal of secrecy?"

"It was. You know how difficult it is to get boys—that is, some of 'em—those with the highest sense of honour—to speak out in such a case. So I had some trouble, and I only learned what I have told you after promising to keep the name of my informant a secret."

"Humph! But how am I to get at the facts if that is the case?" grumbled the captain.

"I suggest that you recall Dawney and question him again in my presence. I think I can get the truth out of him now. And," added the chief officer, with a shrug of the shoulders, "if we find that he has been telling 'fairy tales'—well, unfortunately, it won't be the first time I have found him out in something of the kind."

"Very well, Melfort," Captain Probyn decided. "Send for Dawney."

Meantime Jack had been passing a cold and uncomfortable time up aloft; but he was less sensible of the physical discomfort of his position than of bitterness at the thought of being punished on the very first day of his arrival, and of indignation at the injustice of it.

From agreeable surprise and high spirits he now passed to despondency and a gloomy outlook on life, and as he sat aloft in the fog and darkness—it had been already dusk when he had been sent aloft—he brooded bitterly over what had happened.

Presently, however, there had reached his ears from below some soft scratching and scraping sounds, as of someone stealthily climbing the rigging.

A little later, first Boulter, and then Caryll, had crept softly up, and taken their places beside him.

"It was through taking my part that you were sent here," Boulter whispered, "and I couldn't let you be here alone. I say, it's a burning shame! Caryll thinks the same, and he's come too."

"Thank you!" said Jack warmly, and he pressed Boulter's plump hand. "But is it allowed?"

"Oh, that's all right! No one will know. We shall slip back before we're missed."

So Jack had a better time aloft than had seemed likely at first. His stay was also a great deal shorter than they had expected, for the three had not been very long together when Joyce's voice was heard hailing him from the deck and telling him to come down.

Then they had reason to be glad of the fog, which hid the two interlopers from the sharp eyes of the petty officer.

Jack answered the hail, and came down, while his companions stayed behind till the coast was clear.

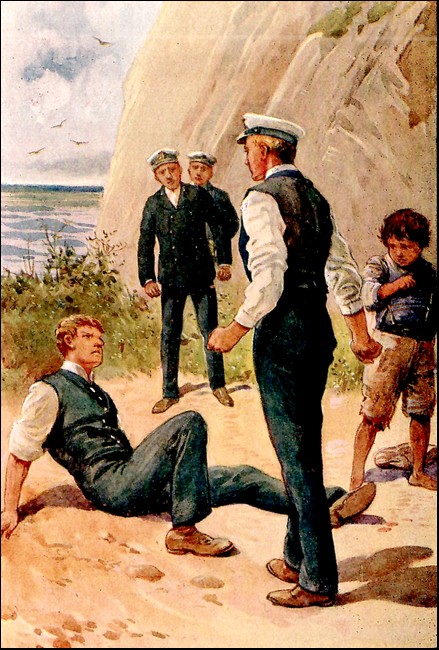

When he reached the deck he was conducted to Captain Probyn, who was awaiting him with his chief officer, and, to Jack's astonishment, the captain extended his hand to him.

"My lad," he said kindly, "thanks to Mr. Melfort's good offices, this matter has now been put before me in a way which leads me to take a very different view of what has happened. I am very sorry that I acted hastily and on insufficient information. The entry will be erased from the punishment-book, and I am free to welcome you, not only in the ordinary way as a newcomer, but as one who brings with him the record of a most courageous action."

"Thank you, sir," said Jack simply, "and I thank Mr. Melfort also."

"Well, now," said the captain, "I want to know more about this affair of the steam-launch. I intend to make inquiries in order to find out what boat it was and who was on board her. Mr. Melfort, will you please send for the other lads who were there. I want to hear their evidence separately."

It was easy enough to summon Steele and Egerton, but at first neither Caryll nor Boulter could be found, the fact being that they had experienced some difficulty in eluding observation in their descent from the masthead. However, they fortunately turned up a little later, and Captain Probyn was not in the mood just then to ask unpleasant questions as to the reason for their delay.

When they had all been questioned in turn they were dismissed, and Jack went off with them to get his first supper on board.

"What's happened?" Boulter asked, as soon as they were free to talk. "We met Dawney and Forder as we came along, and they both seemed pretty down in the mouth. As to Dawney, he looked as if he'd like to eat me, but he didn't say anything."

Jack told them all he knew, which, however, was really very little, and did not throw much light upon the question; but a little later they heard that first Dawney had been sent for by the captain, and then Forder, and they formed their own opinion as to what had taken place.

"Mr. Melfort made 'em own up, I guess," Boulter shrewdly suggested.

"If so, Dawney and Forder will be for having their knives into you, Kendall," Caryll warned him, "so you will have to look out."

JACK felt glad and thankful that his first day on board was not to be stained by a punishment mark, and, that trouble being lifted from his mind, he was full of curiosity and interest in his new surroundings.

As he sat down to supper beside his two chums he wondered a little what he would get to eat, but soon discovered that any misgivings on that score were uncalled for. The menu did not consist of jellyfish, starfish, and the like, as the veracious statements he had heard in the train would have led him to expect.

Certainly, on the other hand, there was nothing savouring of luxury in the diet. It was just plain, wholesome fare, such as he would have expected at any ordinary good school.

For a few minutes little was said. Most of the lads had come back that day, and, having travelled far, were hungry, and not much in the mood for talk.

As the edge was taken off their appetites, however, there arose a low murmur, which gradually swelled into a confused buzz of conversation.

Opposite to Jack was a boy a little bigger than himself, with a thin, freckled, ferret-like face, surmounted by a fringe of sandy hair. This lad, while munching vigorously away at the fare provided, kept looking first at Caryll and then at Kendall.

Jack did not like the way this boy regarded him, and gave back look for look. He felt instinctively that he had here to do with another would-be bully.

Presently, having partially filled the void within, the youngster addressed himself to Caryll.

"Hullo, Baby," he began, "got a new child in tow? Looks like another chip off the Branson block, only wants knocking into shape."

"Baby" was a nickname applied to Caryll, in consequence of the look of baby-like innocence, of which mention has already been made.

Caryll, however, had his mouth full at the moment, and made no direct reply. He only mumbled something about "some boys being chips for blockheads."

Boulter answered for him.

"I wouldn't advise you to try the knocking into shape," he muttered. "One chap's tried it on already, and had to squeal out to his chum to come and rescue him."

This was a reference to the Dawney incident, the freckly-faced lad being one of that young gentleman's followers. He had evidently heard of it, for he looked savage.

"I didn't speak to you," he retorted rudely. "I asked Baby Caryll there."

But the latter was still too busily employed to speak, the questioner addressed himself directly to Jack.

"What's your name?"

Jack looked at him steadily.

"What's yours?" he asked.

"I'm called Skinner. The name was bestowed upon me because I'm always ready to skin any new kid who cheeks me—and don't you forget it!"

"There's another reason," said Caryll, who had got his mouth free.

"What may that be?" Jack inquired, with interest.

"Because he comes of a long line of skinflints."

Jack at that moment stretched out his hand to take a piece of bread. It happened to be the last one on the dish.

"I want that, new kid," said Skinner, and snatched the dish away.

As a matter of fact he did not want it, for he had finished, and he only wished to annoy Jack.

A boy sitting next to Skinner good-naturedly gave the dish a shake, thus tossing the piece towards Kendall, who secured it.

Skinner turned fiercely on his neighbour.

"What d'you mean by that, Horby?" he growled.

At the same time he gave Horby a dig with his elbow.

The assaulted one returned it with interest, and a squabble had begun, when a stern voice called out, "Order there!" and the little storm died down.

Jack glanced in the direction of the voice and saw that it had come from one of the officers, who had his eyes on that part of the table.

"That's Groder, our mathematical master," whispered Boulter. "He's a hard nut. You have to mind your p's and q's with him."

Then he went on to indicate the other masters round the board, and gave their names.

"That man over there is old Brigson, who'll teach you all about the rigging and sails, and initiate you into the mysteries of knots and splices."

"You haven't told me your name yet, new kid," Skinner put in. "I s'pose it's because you're ashamed of it."

Jack flushed up; but before he could say anything Boulter spoke.

"His name's Jack. I don't see why you shouldn't know it—Jack—"

"Comes of a long line of Jacks, I s'pose," sneered Skinner. "Descended from Jack the Giant-killer you'll tell me next. More likely, though, his father was a cheap-jack—"

"You leave my father out of it!" exclaimed Jack, through his closed teeth. "You can say anything you like about me, but leave my father alone. He has not been dead long."

"Oh!" said Skinner; and for a wonder he had the decency to say no more.

Just then came the short grace, which indicated the end of the meal, and all rose from table.

The lads made their way out in a confused crowd, and Jack became separated from his friends. He followed the stream, and was nearing the companion when two or three coming the other way pushed against him. One of them suddenly put out a foot and tripped him up.

Jack fell heavily, and his head struck a stanchion with such force that for the moment he felt half-stunned.

Rising slowly, and looking round in a dazed way to see who it was that had caused his fall, he found himself face to face with Dawney and his (Jack's) cousin, Clement Branson.

JACK KENDALL and his cousin stared at one another for some moments in silence, the while that Jack rubbed at his head where he had struck it in his fall.

He was still too dazed to notice details particularly, else he would have seen the expression on Clement Branson's face change from satirical amusement to apparent friendliness.

"Hallo, Jack!" he exclaimed. "This is a surprise! I'd no idea it was you! How long have you been aboard? Come down to-day?"

He held out his hand, and Jack took it, still scarcely knowing what he was doing. Clement went on:

"My guv'nor said he had heard you were going to join; but he didn't seem very certain about it. However, here you are! How're you getting on?"

"All right," answered Jack, in a noncommittal tone. "Shall soon settle down, I suppose."

Branson turned to Dawney.

"This is my cousin—Jack Kendall. I suppose you haven't seen him yet?"

"Oh, yes," said Jack. "We've met before. We're quite good friends already." And he looked steadily at Dawney. "He knows the sort of chap I am."

But Dawney only scowled, and pulled Branson by the sleeve. "Come on," he muttered; "I want a talk with you."

"See you again presently, Jack," Branson said, with assumed cheeriness, and went off with the other.

"Now, I wonder which of those it was tripped me up?" murmured Jack to himself, as he looked after them. "I feel pretty sure it was one of the two. Suppose it must have been Dawney. Clem would hardly begin that sort of thing just yet; though I can tell he's anything but pleased at seeing me. Well, I'm thankful that I'm not beholden to his father for being here, anyway!"

Then Caryll and Boulter, who had been looking for him, came up, and the three went to the upper deck for a blow before turning-in time.

The fog had cleared off, and the lights on shore and on other vessels lying at anchor in the river could be plainly seen. Above, the moon was shining down with a cold, silvery gleam, and there was a keen, almost frosty nip in the air.

As the three hung over the bulwarks, chatting in low tones, they heard a hail from the officer of the watch, and saw that a boat was nearing the ship.

"The captain's gig," whispered Boulter. "Bringing the young ladies. I suppose they went ashore early in the day, and the old man didn't like to bring them back through the fog."

"The young ladies?" Jack repeated, in surprise. "I didn't know you had young lady cadets."

The other two laughed.

"It's the captain's daughter, Alma, and her cousin, Bertha Fordyce," Caryll explained. "Two jolly girls! They're with the governess, Miss Chalford."

Jack whistled; and he looked on with much curiosity as the boat came alongside and the three ladies climbed the accommodation ladder.

Evidently used to it, they nimbly gained the deck, where they were received by Mr. Melfort, who had heard the hail and had come forward to meet them.

Jack saw, first, two girls about his own age, and then a young lady, whom he supposed must be the governess. She and the chief officer stood talking together, while the two girls looked round.

Groups of cadets were standing about on deck, and they lifted their caps as the girls glanced at them, with a nod and a smile here and there. Then the two caught sight of Caryll, who, as it happened, was the nearest.

They stole across quickly and shook hands with him and Boulter.

"How's Mabel?" one asked.

"Quite well—sent her love to you, Alma," answered Caryll; and Jack knew that the fair young girl with the golden hair, and the laughing, roguish eyes, must be the captain's daughter. The other one was darker, with sparkling brown eyes, and dark-brown hair. Both now stood looking at Jack with a puzzled expression.

Caryll's face lighted up with the mischievous look his new chum had seen there before.

"Aren't you going to speak to Clem Branson, and welcome him back, too?" he asked.

One of the girls—it was Alma Probyn—put her hand out slowly, and, as Jack thought, rather coldly.

"Sorry!" she said, "I didn't—" And then she drew back, as her friend Bertha laughed.

"It's not Clem Branson, Alma; I saw that almost directly," she said. "That's a bit of Will's nonsense. It's someone else—a new boy!"

"That's right!" Caryll put in, quite unabashed. "It is a new chum of ours—Jack Kendall is his name. But he's a cousin of Clem Branson, anyway."

"Oh!" murmured Alma; and Jack noticed that the announcement of the relationship was not received with any enthusiasm. She was once more about to shake hands, however, when the voice of the governess was heard calling. And with a quick good-night, to Caryll and Boulter, the two hurried away.

As to Jack, he was left in a very confused state. The meeting with the two girls had been so sudden, and so utterly unexpected, that he had, for the moment, quite lost his presence of mind. He reproached himself now for having stood there and never said a word.

"You look flabbergasted!" said Caryll, giving Jack another of his mischievous glances.

"Not used to ladies' society, evidently," Boulter commented. "We'll have to educate him up to it. Quite took him aback."

"It was rather a surprise," Jack admitted, with a laugh. "I never expected to meet any girls here. Who's Mabel?"

"Mabel's my sister," Will Caryll explained. "These two come over to our house sometimes to see her."

"Oh, I didn't know you had a sister. You didn't mention her when you told me about your home, you know."

"It isn't his fault," Boulter observed. "Chaps can't help having sisters. I've got two myself. However, you'll find Alma and Bertha a good sort. You needn't be afraid of them. They're not stuck up, and don't give themselves airs, as some would, because they're the captain's girls."

The talk changed to other matters, and Jack's companions gave him various bits of information about the ship and his fellow- cadets.

One of the most noteworthy was that the first-term cadets were sub-divided informally into two lots, one lot sleeping in a dormitory on the starboard side of the vessel, while the sleeping-place of the others was on the port side.

There was a certain amount of rivalry between the two sets; and they were known as Light Blues and Dark Blues respectively. Each set had a leader, whom they styled their captain: the captain of the Light Blues—to which set Caryll and Boulter belonged—was named Neville; while the leader of the Dark Blues was called Vyner. This division, however, was not recognised by the officers, but was purely a custom amongst the cadets themselves which had been handed down, as Boulter declared, "from time immemorial."

"They're a wild, mischievous crew, the Dark Blues," he went on. "They're always trying to plan out some fresh prank to play on us."

"Ah, yes," Will chimed in, with a reproving shake of the head. "You never know what trick they'll be up to next."

"Of course you never play any tricks on them in return?" Jack remarked, with becoming gravity.

Caryll stared at him with a look of wondrous innocence.

"Of course not!" he exclaimed, as though shocked at the mere suggestion. "Think of the example we're expected to set! It would never do for us Light Blues—"

Just then there was a sound as of someone talking angrily, yet in low tones, so as not to attract the attention of the officer of the watch.

A group of three or four boys came in the direction of the chums, the boy Skinner in the midst of them. As they got close, Skinner suddenly let fly something at Caryll. It was something pretty large, and seemed to be shot out of a handkerchief, sling fashion.

But Will, who was evidently on the alert for something of the sort, cleverly ducked, and the thing thrown, passing over his head, came full at Joyce, who was coming from the other direction.

It was an immense jellyfish; and it landed on the side of his head and neck with a loud, plump squelch, and scattered in all directions.

"You impudent young monkey!" spluttered the petty-officer, as he made a run and seized the thrower. "I'll report you for this! Come with me!"

"I didn't mean it for you, Mr. Joyce," pleaded the delinquent. "I threw it at Caryll, there. He put it in the pocket of my jacket while it was hanging up, and I found it there when I put it on and slipped my hand into the pocket. Horby saw him there at the time. I only meant to give it him back."