RGL e-Book Cover 2017¸

Roy Glashan's Library. Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover 2017¸

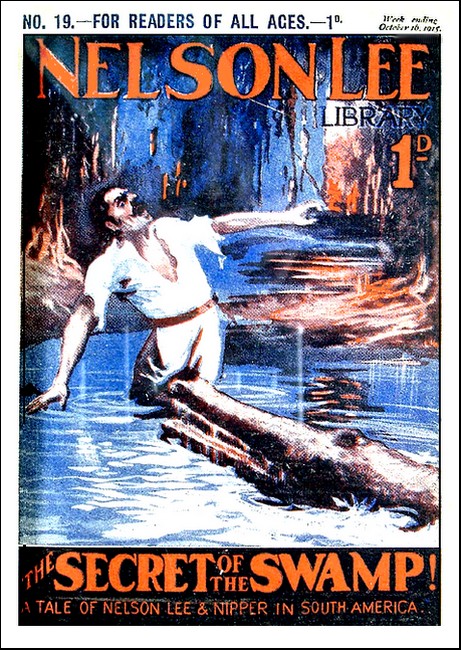

Nelson Lee Library, Oct 16, 1915, with first part of "In Polar Seas"

THE works of "Fenton Ash" are highly prized among bibliophile collectors of classic sci-fi and fantasy. At the time of writing (October 2016) a copy of the rare novel The Radium Seekers, for example, was being offered at AbeBooks at a price of over 1,200 US dollars.

The present novel—In Polar Seas; A Romance of Adventure in the Frozen North—appears here for the first time in book form. Serialised in 1915-1916 in The Nelson Lee Library, a British pulp weekly targeted mainly at juvenile readers but billed as being "for readers of all ages," it describes the adventures of a team of British explorers who discover a lost Viking civilisation in a hitherto unknown temperate zone near the North Pole.

This RGL first edition was prepared from image files of the novel as it was printed in The Nelson Lee Library. The section headers of the serial version, which in some cases do not accurately reflect the actual contents of the section to which they refer, have been retained. Chapter numbers have been added. Footnotes have been added to explain obscure terms.

—Roy Glashan, October 2016

Chapter I.

On Greenland's icy shore—Suspicious neighbours—A raid on

the camp.

Chapter II

The raid renewed—How it was met—Three to one—a

startling collapse.

Chapter III

A great find!

Chapter IV

Trouble with Grimstock—The skipper and his men—ruxton's

forebodings.

Chapter V

Ruxton is amused.

Chapter VI

The first motor-sledge—Eskimo dogs disapprove running

amok—a plucky rescue.

Chapter VII

Ruxton's warning—Amaki's strange request—A midnight

assassin.

Chapter VIII

The assassin—Who was he?

Chapter IX

Left to die in the white wilderness.

Chapter X

Val tells Hugh some plain facts.

Chapter XI

An unexpected sight—Mirage or reality—Hope for the

castaways.

Chapter XII

"Is it a mirage?"

Chapter XIII

A night in a snow-drift—The motor-sledge abandoned—The

last of the food—A surprise.

Chapter XIV

A land of fire—A sail across the ice—Shot off a

glacier.

Chapter XV

In a new land—A gruesome find—Illuminated

caverns—Attacked by strange monsters.

Chapter XVI

A terrible fight.

Chapter XVII

A wild fight with weird foes—A night attack in

force.

Chapter XVIII

Defending the cave.

Chapter XIX

Besieged by the yellow-haired monsters—A tough

struggle—Hugh loses his temper.

Chapter XX

Matters become serious.

Chapter XXI

"Caliban's" peace offering—Mike's discomfiture—a

startling apparition.

Chapter XXII

The banner of Odin and the war-song of the Vikings—Dr.

Fenwick's theory—prisoners!

Chapter XXIII

The Vikings of old.

Chapter XXIV

Hugh's defiance—A duel with a Viking.

Chapter XXV

The Vikings' home—Osth the Hard and Hertseg the

Fighter—Hugh loses his temper again.

Chapter XXVI

A free fight—Arrayed in armour.

Chapter XXVII

The great wrestling match.

Chapter XXVIII

The struggle in the cage—A mysterious warning—A double

duel—The alarm.

Chapter XXIX

Preparing for the battle—The spell of the "Berserkers."

Chapter XXX

The "Berserker"—How the chums captured a

war galley, and what followed—A new mystery.

Chapter XXXI

Friends to the rescue!

Chapter XXXII

Chained to the oar—A mysterious friend—The Vikings give

chase.

Chapter XXXIII

The last fighT—Father and son—Conclusion.

"NOW I wonder who those fellows are down yonder, and what their little game is in pitching their camp so close to ours? By the noise they're making they seem to be a pretty rowdy lot! We must keep an eye on 'em. I don't like either their looks—what I've been able to see of them—or their voices. Mike, lad, wake up! Put some more wood on those fires! What are you pulling such a long face about?"

The scene was a desolate strip of snow-covered shore in the far North. The wide stretch of ice in front of it was a part of the great frozen sea; while the frowning crags, and giant, snowy peaks, which formed a forbidding background, were offshoots of "Greenland's Icy Mountains."

Upon that dreary shore, which looked more dreary than ever in the cold moonlight—the short Arctic day had closed in a couple of hours before—there was an unusual sight—no less than three separate encampments.

For most of the year this snowy waste, known by the native name of Amanstok, is the undisturbed playground of seals and walruses, of bears and blue foxes, and of myriads of Arctic birds.

Once or twice a year a wandering band of Eskimos choose it as their halting-place on their way to or from the great hunting grounds beyond.

This, again, is what had happened now; for Hugh Arnold, the young fellow who had uttered the words which have just been quoted, belonged to a band of Arctic explorers just out from England; and their ship, the Petrel, lay at anchor some half dozen miles away. This, then, accounts for camp No. 2.

But the people at No. 3 camp were what mathematicians would designate by the letter A, being, at present, an unknown quantity.

The most likely supposition would be that they were a hunting party sent out to forage for fresh food from some whaling ship not in sight. The crews of such vessels are frequently a lot of desperadoes, the maritime scourings of many nations. They are not usually, therefore, much to be desired as close neighbours, especially when, as was evidently the case here, they are out by themselves, and so are beyond the reach of the iron discipline which alone keeps them on their good behaviour while on board ship.

These particular men, to judge by their proceedings, were of this kidney. They had been for some time yelling out ribald songs and choruses; and just lately sounds had been heard suggestive of drunken brawls.

The No. 2 camp—situated mid-way between the others—consisted of half a dozen tents, two or three sledges, and a number of packages, which had been brought over the ice from the ship and hastily dumped down just before nightfall.

Then most of the landing party had gone off to No. 3 camp to foregather with the natives, leaving at first only Hugh in charge. He, however, had been joined, just before, by an Irish sailor, one Mike O'Grady, who, tiring of the native style of entertaining guests, had returned to camp alone. There he had seated himself in silence, smoking stolidly at his pipe, and looking particularly glum and unhappy.

As to Hugh himself, he was a very tall young fellow, far above the ordinary height, and even the thick clothing in which he was enveloped could not conceal the fact that he owned a frame that was massive and muscular beyond the average.

This fact was revealed less by the outline and general shape of his figure, than by the peculiar, easy grace of his movements as he strode to and fro, the light springiness of his step, and his general carriage. He bore himself as does the lion, with that indescribable swing of the limbs which betokens so unerringly a store of conscious strength and latent energy. In fact, he was known amongst his fellow travellers by the sobriquet of "Strong Hugh."

"I've been wonderin', Misther Hugh," answered Mike, as he stretched his great figure—for he, too, was a big man—and made a move, towards some piles of wood, "whin we moight be goin' to get t' this green land as I've heerd so much talk about."

"Why, you great nincompoop, this is Greenland. I thought you knew that."

Mike stopped suddenly in the act of picking up his wood, and appeared so startled that he nearly dropped it again.

"Whoy—whoy!" he exclaimed, with a look around of comical dismay. "Wheer be the green? It's meself as can see nothing' but white. I thought for sure as Greenland must be further on."

Hugh laughed.

"No, my friend, you'll meet with no greener land than this. There will be some green here later on—when the season is a bit further advanced—but we sha'n't get much of that."

"Begorrah! Divil a Bit, thin, wad I 'ave come on this precious thrip, sorr, iv I'd bin tould that same before. They said t' me, 'Will ye come on a thrip to find the North Pole?' an' I said, 'Which way did 'e go?' an' they said, 'By way av green land.' 'If theer's a way through a noice green land,' sez Oi, 'thin, bedad, Oi'm the bhoy for ye! I always thought it was oice an' snow ye had to go through out theer.' Thin the bhoys laughed an' said, 'Oh, no: we're goin' to a green land roight enough.' An' now I sees that it's decavin' me they was—the merry divils! Oi'll be even wid some av thim over this!"

"Never mind, Mike. It'll be a fresh experience for you. You've been pretty well all over the world, I've been told—"

"Thrue for you, sorr. I have indade!"

"Except in the Arctic. Now you'll be able to say you've been there, too: and to the very Pole itself, if we get there, as I hope we shall, and then you'll share in all our honour and glory."

"Will we iver get back, sorr? That's the question as concarns me most. Sure, Oi'd go back on the next ship, now, iv there was one goin', an' Oi'd be afther lavin' ye me share av the honour an' glory, free an' for nothing'."

Hugh laughed again, a free, easy, good-humoured laugh, and turned his glance in the direction of the Eskimo camp, from which also came sounds of singing, and a rough kind of music.

"Ah!" he said, in a tone of satisfaction. "Here are some of our chaps coming at last! I wonder why they've been staying all this time, and what's going on there? Humph! It's only Mr. Ruxton and Bob Cable after all. What are the others waiting there for?"

"It's a bit of faystin' an' merry-makin' goin' on theer to-night. The pure haythins don't ofthen get our sort here, t' giv' thim little presents; an' they're returnin' the compliment by givin' a fayste."

"Yes, I understand that. You didn't stay there long, by the way, Mike. You seem to have grown tired of it sooner than these others have."

"Toired? No, it wasn't so much toired I was, as sick, sorr. Sure, the haythin's idea av a fayste is a good fat taller-candle, wi' a drink av train oil t' wash it down. It's meself as couldn't stand anny more av it!"

"You'll get used to that sort of thing out here, Mike. Hallo, Val! Here you are at last! What's kept you so long? Where are the others?"

This query was addressed to the one the speaker had spoken of as Mr. Huston. He had now come within earshot.

"Left 'em down there with the oil-bibbers," said the newcomer, crossly.

"You shouldn't have done that."

"Couldn't get 'em away. They're in a frolicsome mood—effect of getting ashore and feasting on too much whale blubber, I suppose, after being cooped up so long on board ship. They're making friends with some of the Eskimo beauties, and having a dance now; and the fun seemed to be getting fast and furious. So Bob and I—Bob's the only sensible one among the lot—cleared out and left 'em to it."

"I say! You should have made 'em come with you! There'll be trouble over this in the morning. Grimstock will fume and rave nicely about it if he hears of it—and he's pretty sure to."

"Can't help it—he'll have to fume. They simply won't listen to me."

"We'll have to go back there together and make 'em listen."

"Wouldn't go if I were you, old chap. They've got some drink into 'em, and are in a nasty humour. Best let 'em have their fling and come back their own way. Besides—"

"Besides—what?"

"Well," said Ruxton, in a low lone. "I've come back here now partly because I wanted to have a word or two privately with you while Grimstock's out of the way. We don't often have a chance for a quiet chat without any fear of being overheard. Certainly, there wasn't one so long as we were on board ship."

"If that's the case, of course it's another matter," replied Hugh wonderingly, and evidently impressed by the grave tone in which the other spoke. "Only, I'm afraid trouble will come of it."

"Trouble will come of it—it's sure to—either way, so it may just as well come one way as another," was the answer, delivered with an indifferent air. "Come for a short stroll with me. Hallo! What's that row?"

"Those fellows yonder suddenly appeared from nowhere, just after you had gone, swarmed along here, and plumped themselves down where you aee them. They seem a rough lot. They started on a carouse, and now comes the usual sequel—quarrelling—with fighting, I expect, to follow. Just listen to 'em now! But who are they? White men, do you think?"

"White men? Mm! Pretty low-class whites. I guess, if there are any: and us for the others, they're likely to be of all colours—brown, black, red, and yellow—and there would be blue and green, if such people existed. Some whaler's crew, I reckon, with a skipper who's drunk one half his time, and a raging, bullying maniac the other half. The farther we can keep away from 'em the better."

"Just my view, and I'm glad you've come back, because there's no knowing what a drunken lot like that might take it into their heads to do. They might take a fancy to divide up some of our stores, and, if so, there an only two of us here to deal with the crowd. By the way, what was it you wanted to say?"

Ruxton did not reply at once, but putting a hand on the other's arm led him away a hundred yards or so. No. 2 camp had been pitched upon an elevation forming a sort of terrace, which extended for some distance. Ruxton walked nearly to the end of it, and then stood looking thoughtfully down at the sealskin tents of the Eskimos, which could now be seen more plainly on the shore below.

He was a fine-looking man this Val Ruxton, not quite so tall as his companion, but sturdily and heavily-built, with keen eyes, and a firm, determined face. He was evidently the older of the two by a few years. He was the darker, too, and his face was more tanned, the face of one who had travelled far and often, and seen much of the world.

"Look here," he said, at last, with sudden decision, as though he had been pondering what to say. "I don't think much of this Grimstock crowd we've come out with. I never did think much of 'em, but something's happened which has sent my opinion down lower still. You and I are strangers to one another, except that we've cottoned together a bit on the voyage out, and, frankly, I like you, and feel a sort of interest in you. See?"

Hugh laughed quizzically.

"Shure, an' it's a noice, iligant gintleman ye are, Misther Ruxton," he said, imitating Mike's familiar brogue. "Shure, it's meself—"

"No, no; I'm not joking," Ruxton interrupted, with a seriousness that had an instant effect on his companion. "I'm going to ask you a straight question. What made you join this show?"

"I might ask you the same question."

"You might—and you may—and I would answer at once. I do answer at once. It was a question of money with me—money, pure and simple. I was just about stony when Grimstock came across me. He wanted another man; we had a talk; he soon learned that I had been out here before and knew the ropes, could speak the native lingo, and so on. So he made me an offer; I closed with it, and here I am. And I'm beginning to wish I wasn't."

"Why? What's upset you?"

"Never mind that for the moment. You haven't replied to my question, though I've answered yours."

"Well," said Hugh slowly. "I can only give you a somewhat similar reason."

"No! I don't think it was a matter of money with you," Ruxton declared, with quiet insistence. "I heard that you sought Grimstock out and brought letters of introduction."

"How do you know that?"

"Never mind that just now. It is true, isn't it?"

"Why, yes; that's right enough. The fact is, I've long had a wish to come out here. It's been a—well, a sort of passion with me, ever since I was a kid. I made up my mind I would get out here some day by hook or by crook, and I prepared myself for it in every way I could think of—by travelling in Norway, and Lapland, and Ireland, and so on. But I hadn't money enough to fit out a regular expedition of my own to come so far north, so I had to join in with someone else. I heard that Grimstock was preparing one, and I offered myself. As you say, I brought letters of introduction to him, though how you knew of that, of what it has to do with—"

"It has a good deal to do with what I wish to speak about, as you will see directly. You are known to us as Hugh Arnold—"

"Well? Don't you like the name?" Hugh asked, chaffingly.

"My dear fellow, I don't care a brass dollar what your name may be. As I've told you, I like what I've seen of you since we first met, and I should like you just as much under any other name—John Smith, or Clifford Vere de Vere, or Obadiah Macandlestick. I just wish to give you a hint that if Hugh Arnold is not your true name, and you are hugging to yourself the idea that you have concealed the fact from Grimstock, I fancy you will find one day that he knows more than you think for."

Here, the listener started, and seemed about to utter a protest, but the speaker waved his hand and went on rapidly.

"Don't say anything! Don't tell me! I don't want to know! I'm not the sort of chap to want to pry into any man's private affairs. I only give you the hint for what it may be worth, and, of course, it may be worth nothing at all. Well, then, there is another thing. To-day, talking to old man Amaki, one of the Eskimos, down at their camp yonder, he asked me if any tidings had ever been heard of a certain traveller, an Arctic explorer, whose name is pretty well-known in the scientific world. He went north a good many years ago, and neither he nor any of those with him was ever heard of again. Well, old Amaki knew him, it seems—and so indeed did all his tribe—or those of them who are old enough to remember him, and they spoke of him with feelings of evident affection and devotion. I declare that tears were in the old beggar's eyes. Hallo! What's up now?"

Hugh had started again at the latter part of Ruxton's speech, and looked hard at him, but now he had turned, and was gazing back at the camp they had just quitted. It was but a hundred yards or so away, but the tents on one side hid the men they had left in charge from view.

"There's something going on there," said Hugh, quickly. "I expect it's some of those scalliwags come up to make a row. I half expected this! Why aren't our chaps here to guard the stores, instead of fooling down yonder?"

While speaking, he had been walking sharply back to camp, and Ruxton walked beside him.

Turning round by the end tent they came suddenly upon a strange scene.

Half a dozen men from No. 3 camp had come up to the terrace on which the No. 2 camp stood, and two of them were engaged in a hand-to-hand struggle with the two sailors who had been left in charge, thus keeping them at bay, whilst their four companions were coolly walking off with some of the packages.

One glance was enough for the two who had returned, and who saw the goods of which they were in charge being thus impudently carried off. Taking in the situation, they made a rush for the thieves. A blow for each in turn was sufficient to knock them over. Loaded as they were, taken by surprise, half-drunk into the bargain, they were not in a position favourable for preserving an upright position.

So down they went, and there they lay for a space, wondering where the earthquake had come from, by what time those who had brought them low were busy carrying back the stolen property. After a minute or two, however, the snow into which the raiders had fallen, exercised a reviving effect upon their beclouded brains. They began to aee and understand a little more clearly. Then they rose up, wrathful and revengeful, and swearing in various languages, they went for the two who had so roughly toppled them over, and caused their mouths and nostrils to be filled with disagreeably icy snow.

Meantime, Hugh and Ruxton, having put down their rescued goods, had gone to the assistance of the sailors, who were still struggling manfully with two burly assailants.

Just then it was that the other four marauders, having recovered themselves came on at a run, and for the next two or three minutes, the space in front of the tents was peopled with a tussling crowd, a mix-up of whirling arms and legs and panting bodies.

Blows were freely given and received, and a good many kicks, too: there were gasps and growls, snarls and guttural roars that sounded more like a wild-beast fight than a trial of strength between human beings.

It did not last very long. Neither Hugh nor Ruxton was in a mood to stand any nonsense, and one by one all the intruders were expelled. This time they had the misfortune to be hurled off the terrace into a snowdrift just below, which, as it turned out, was so deep that they disappeared completely from sight.

Then the victors were able to enjoy a hard-earned breathing time. But it was not likely, they knew, to last long. The noise of the conflict had been heard at No. 3 camp, and from it a reinforcement quickly started forth to the aid of their discomfited comrades.

"END of first round! 'Vantage to us!" said Hugh, with a short laugh.

"Yes," Ruxton assented. "But that was a pretty soft job. The real tug is yet to come. We shall have double the number on to us next time!"

"And our men are down yonder philandering with those native beauties!" exclaimed Hugh bitterly. "We'll have to talk to those gentlemen in the morning."

"Grimstock will talk to 'em, you may be sure, and to us as well. That's the worst of it. We're likely to get all the hard knocks to-night and more than our share of hard words afterwards, or I'm no prophet."

"Oh, well, hard words don't break bones," returned Hugh cheerfully. "And as to hard knocks—why, I felt just in the humour for a jolly good rough-and-tumble to-night. So let 'em all come! It'll help to circulate the blood and keep, you warm."

"H'm, I've no objection! But now, while we've got a minute or two, we'd better move those packages to a place where they'll be more out of the way; and safer, too, than lying out here."

"Right you are. Where shall we put 'em?

"I'll show you," and picking one up, Ruxton led the way towards the tents.

Of these there were six, which had been pitched in two rows, a little distance apart, and Ruxton soberly deposited his burden in the midst of them—that is to say, behind the first row, but in front of the second. His companion brought further loads, which Ruxton then arranged in what struck Hugh as rather an eccentric fashion.

"What's the good of putting them down there?" he asked. "For my part, I should have thought it would have been better to put everything in the tents out of sight."

"Not at all!" Ruxton declared coolly. "You'll aee, by-and-by, that its best not to put them out of sight."

Hugh could not at all understand his friend's reasoning, but he said no more, and, all the moving having been accomplished, he went back to join the sailors who had been left on the watch.

Ruxton remained for two or three minutes more, apparently shifting packages here and there to get them exactly to his satisfaction. When he finally joined his companions, he was carrying a brace of revolvers and offered one to Hugh, who, however, at first declined it.

"Thanks, but I'd rather trust to my fists." he remarked. "Besides, I hope it won't come to shooting, whatever happens."

"Quite right, and I hope so, too. In fact. I don't think these chaps would be foolish enough to begin it, as they must know that any shooting would he heard on board our ship, and would bring a party about their ears pretty sharp. It's their knives you'll have to look out for. These beggars are apt to get murderous when their blood is up. So it's as well to keep the barkers handy, in case we're hard pressed."

"Oh, very well," said Hugh, nonchalantly slipping a "barker" into a side-pocket. "Anything for a quiet life."

There was a quiet chuckling from the two sailors. The last words were rather a favourite expression with the speaker, and he sometimes used them under odd circumstances. More than once, on the voyage out, "Strong Hugh" had brought his fists into play in a very pretty fashion in the interests of discipline. It had sounded a little quaint on such occasions to hear him, while giving some brawny, mutinous ruffian a hammering which made him sore all over for the next four weeks, calmly remark:

"I hate to do this, you know, but still, anything for a quiet life."

Just then, Mike who had been routing about amongst the wood pile, turned up with his arms full.

"Shure," said he, "if anny av you gints wants a shillelah, it's some handy bits av rods I've found."

As a matter of fact the "bits av rods" were whacking great chunks of wood.

"To be sure! The very thing!" cried Hugh, pouncing on one of the biggest—a heavy, massive affair that would have made a likely club for Hercules himself. "Mike, lad, ye're a broth av a bhoy! I'll recommend ye for promotion. Ye shall have an extra ration av train oil for breakfast."

Mike grinned appreciatively, and their preparations being completed, they all turned their attention to watching the movements of their enemies.

As to these, the new men—six in number—who had sallied forth to the assistance of their pals, had been compelled to restrain their martial ardour, and delay the intended assault, in order to dig the latter out of the snowdrift into which they had vanished.

Four or five great white masses had by now been routed out from its icy depths, and propped up on their somewhat shaky legs. At first they looked like big, roughly-manufactured snow men, but after undergoing a sufficient amount of shaking and brushing-down they had gradually resolved themselves into dark, skin-clad human beings, who spluttered out mouthfuls of snow and curses, mingled together in about equal parts.

This preliminary accomplished, they held a short conference in low muttered tones, and were then on the point of arranging themselves in military order—or something as near thereto as their obfuscated intellects could figure out—when some stifled cries and groans, mingled, of course, with the proper seasoning, from out another part of the snowdrift, once more interrupted operations. A rush in the direction of the sounds, and some wild scrambling and burrowing in the snow, resulted in the recovery of another snowman. This was, as a matter of fact, none other than their redoubtable leader himself, though it was some minutes before his identity was established, for the reason that he was hauled out legs first. These, his rescuers, with well-meaning wrongheadedness, persisted in holding up in the air, evidently under the impression that they were thus supporting his head.

The more the unfortunate wight struggled and kicked, the more obstinately they held on to his legs. The more he tried to shout and explain matters, the more they forced his mouth down into the snow and choked his utterance.

How he managed to escape being suffocated was something of a marvel. Ruxton, however, afterwards declared that it was due to his sultry language, which eventually thawed the snow round his head and so enabled him to make his voice heard.

Anyway, he somehow got free, bounded up like a jack-in-the-box, and began hitting out all round, sending his zealous rescuers spinning, and letting fly such a string of oaths as left them in no further doubt as to who it was they had so perseveringly kept buried in the snow.

Suddenly, his flow of ornamental language was cut short by a well-aimed missile from above; which caught him full in the mouth. It was nothing more nor less than a snowball, and it was thrown by Hugh, who, inspired by a sense of humour, thus contemptuously showed his opinion of the swearer.

The defenders had been watching the proceedings with great interest, almost shaking with laughter the while. Then Hugh had suddenly bent down, rolled up a good handful of snow, and flung it at the raving ringleader.

In an instant the other defenders caught at the idea, and, joining in the fun, they bombarded the enemy with snowballs as fast as they could make them.

Now, though this had been done without premeditation on Hugh's part, in what Mike would love characterised as a fit of pure "divilment," it turned out to be a really clever bit of strategy.

For here, below, were a dozen men in reckless mood, their passions inflamed by drink, and their cupidity excited by the knowledge that just above them were all sorts of good things—tobacco, doubtless, for one thing, to say nothing of plenty of drink—freshly brought out from England. There were only four men to defend all those desirable luxuries, and yet those four had the impudence and audacity to insult the twelve by snowballing them as though they had been but a parcel of schoolboys!

So exasperated did the twelve feel at this unexpected treatment, that they threw all discretion to the winds. Instead of taking counsel together and forming some definite plan of attack, they simply turned and rushed blindly, madly up the slope.

The slope formed the only direct way of reaching the terrace at that part, but it was not a good way, for it consisted of hard-frozen snow, with impassable drifts of loose soft snow on each side of it. There was only room on the slope for three or four men abreast, and it was certainly none too favourable ground for the excited rush of an angry crowd, such as those who now charged up its slippery surface.

On they came, a disorderly mob, three or four deep, the back rows helping to push the front ones on and prevent them from sliding back. Struggling to keep their feet, and half-blinded by the snowballs with which the defenders continued to pelt them, they nevertheless managed to scramble to the top, or very near it.

Several of the men had drawn their knives, and the shining blades glittered with a cold gleam in the moonlight. Hugh noted this, and his face grew stern as he pointed them out to Ruxton.

"You see those beggars, Val," he said. "We'll go for those cowardly brutes first! You take the right hand men, and I will deal with the others to the left."

Just as the leaders of the assailants had all but reached the top, they received an extra instalment of the snowy fusillade, and ere they could clear it from their eyes the defenders made their rush.

Whirling their formidable clubs in the air, they brought them down, first on the arms and hands that carried the knives, then upon the heads and the shoulders of their owners.

Blow followed blow, crash upon crash. So fierce and determined was the counter-attack that the front rank recoiled upon the next. Two men slipped and fell, causing others to trip over them.

Then, judicious prods with the heavy clubs, driven home with all the strength and weight of the men behind them, sent the reeling "corner men" toppling off into the drifts at the sides, where they sank out of sight as others had done before them.

The defenders paused, and once more could not refrain from laughing, as they saw the predicament their foes were in. The rear ranks were still on their feet, and they were brandishing various weapons, cursing, swearing, and threatening all kinds of horrible things. But between them and the defenders was a tangled group of fallen warriors, likewise swearing and spluttering, striving vainly to recover their footing on the treacherous slope, and meantime blocking the way against their own infuriated friends.

"If we'd only got something to shove down on 'em," cried Hugh laughingly, "we could—"

At that moment, as he was casting his eyes around for a likely menus of carrying out an idea that had occurred to him, one of the enemy—it was the ringleader himself—recovered his feet and darted upon him, knife in hand

A warning shout made him turn only just in time. A hand, bearing a naked blade, had already been raised aloft, and in another second would have fallen, when Hugh seized the wrist and closed with the ruffian. Then followed a short but strenuous wrestling bout. The leader of the raiders, exasperated by his previous failures and all that had happened since, had worked himself up into a state of almost maniacal fury.

He was a great hulking ruffian, as big as Hugh himself, and doubtless, he expected to easily master him.

But in this he was mistaken. His brute strength was no match for the hardy young Britisher. The struggle was a desperate one while it lasted, but it was soon over. With a mighty effort Hugh threw him from him, and hurled him off the terrace, and once more he vanished from sight in the soft bed of snow below.

Panting, but still smiling, Hugh then turned to the sailors.

"Mike!" he cried. "Bring one of those sledges over here. The first one will do. And be tarnation quick about it! Lend a hand, Bob, sharp!"

Scarcely sooner said than done. Both sailors ran for the nearest of the sledges which were lying on one side, and rushed it across the snow to where their leaders stood.

"Good business!" exclaimed Ruxton, catching Hugh's idea at once. "Swing her round, lads! Broadside! So! That's the ticket!"

"Now, boys! All together!"

The heavy sledge was swung round so that it lay across the top of (he slope. Then, all four, putting their backs into the work, pushed it over sideways in such a manner that, it went hurtling down, broadside on, driving before it, with irresistible force, all in its way.

Downwards it swept, and downwards, in front of it, like shavings before a broom, went the assailants, those who had so far kept their feet striving vainly to resist its descent.

They might as well have tried to stop an avalanche. A second or two later they were all lying at the foot of the slope, plunging about, kicking, fighting one with another, with the sledge almost on top of them.

The defenders had been very near to sliding down too, for they had pushed at the sledge with such energy that it almost carried them with it, and they, had only let go just in time to draw back.

But the marauders were not vanquished even yet, and this time they recovered themselves more quickly than one would have expected.

The last experience bad a distinctly sobering effect, and some of them promptly set to work to pick up their fellows and prepare for another assault.

Their leader was once more dug out, and this lime was set on his legs at the first attempt. Raging and furious, he pointed to another slope further along, where there was greater width, and the ascent to the terrace was more gradual.

"H'm! They're going to have another try," said Ruxton, "and it looks as if there's a little more method in their madness. They're warming up to their work and getting the drink out of their brains a bit. We shall have a harder task this lime. They'll be able to come on all at once."

"WELL, we'll fight 'em, all the same," said Hugh, through his set teeth. "And if I get my hands again upon that treacherous, murderous scoundrel who tried to knife me, I won't let him off so easily."

"We must try another way, I'm thinking," returned Ruxton, thoughtfully. He looked across at the tents. "It's those stores they're really after, you know—not us. If—"

"Why! Surely," exclaimed Hugh, in astonishment, "you don't propose to surrender—"

Ruxton smiled; then, stepping up close, whispered a few words in the other's ear.

Hugh stared, looked at the tents, and laughed.

"Think it could be done?" he asked.

"We can but try it. I think it will work all right. I thought of it before, and I've already prepared the way a bit." Hugh laughed again.

"Right-oh! I'm game to try it," he said.

Ruxton gave some instructions in a low tone to the two sailors, and then they all set to work to move the other sledges to the top of the slope. There they arranged them in such a manner as to form an obstacle to any further attack at that place, and then turned to watch their adversaries, who were already moving in a small crowd to the spot they had selected for the next attack. But they were not all going that way. Three were seen limping off in the opposite direction—i.e., back to their own camp.

"Those three chaps have had enough of it," Hugh observed. "Three the less for us to deal with, at any rate. Come, that only leaves about two to one. I think we ought to be able to manage that, eh?"

"Oh, they're likely to keep us on the move all night at this rate," said Ruxton testily. "For my part, I want to get some sleep before Grimstock turns up here in the morning. I think you'll find my plan's the best."

They left one man—Mike—in charge of the sledges, with instructions to keep out of sight and only show himself in case of any flank movement. Then they strolled along the terrace to the place where they expected the next attack would be made.

They had not long to wait. The enemy came up at a run, determined to rush the position and sweep aside all resistance this time, and the conditions were so much more favourable that they certainly looked like succeeding.

It even seemed as though the three defenders thought so, too, and had decided to give up the contest; for instead of boldly meeting the rush, as had been expected, they suddenly turned tail and ran off!

With a great roar of derision and triumph the raiders swept on after them, and followed so close that the fugitives were hard put to it to escape. In their panic they tried to hide by diving in amongst the tents, and the pursuers darted in after them.

They were not quite quick enough to catch them, but they found something else which, after all, was what they had really come for. These were the packages they had so coveted; what was more, some of them were ready opened for them, and what was still more, it was seen that two of them, at least, were filled with tobacco.

What a find! What a windfall! Here was treasure indeed! As to the miserable, cowardly runaways, who was going to trouble to chase them while this treasure remained awaiting the first comer?

In a trice the two open cases were set upon by the leaders. A moment later their followers, realising what was afoot, swarmed in amongst them, and began jostling, pushing, wrestling, each fiercely determined that he was not going to be done out of his share.

Suddenly a whistle was heard, and simultaneously the six tents tumbled over like so many houses of cards, burying the struggling crowd under their ample folds.

AS Hugh came out on the terrace he was set upon by a couple of the raiders, who, perhaps more wary than the others, and suspecting some kind of trap, had remained in front of the tents. While he was engaged in a bout of fisticuffs with these two, Mike came running up to his aid from the sledges near which he had been concealed, but Hugh would have none of it.

"Leave 'em to me, Mike," he called out, "and get some rope ready to tie 'em up with."

As he spoke, one of the intruders went down under a sledge-hammer blow which rolled him over like a rabbit. The other one thereupon rushed in, and the two closed.

Mike would have liked well enough to stand aside and watch the play, for the man on the ground lay quiet enough. But in obedience to orders, he promptly produced a piece of cord, and knelt grinning beside the fallen foe.

"Sure, ye're a nice spalpeen t' come thavin' round here, kapin' honest men out av their beds loike this," he remarked, as he deftly slipped his rope round the man's body and tied his arms to his sides. "Lie theer till ye're ready t' listen t' raison."

He finished his work, and was in the act of rising to his feet to see how things were progressing with his leader, when he was bowled over and laid flat, and his head bumped on the frozen ground, by a heavy body which came hurtling through the air right on top of him.

He struggled out from under it, and found that it was Hugh's antagonist, whom that muscular young Britisher had picked up and flung down, very much as though he had been a bale of cloth.

"Faith, an' it's a bit careless, ye are, Misther Hugh, as t' wheer ye throw yer lavins," said Mike, as he rubbed his head.

"Hallo! I forgot you were there, Mike! Hurry up with some more rope for that chap. I must go and help the others. Come to us as soon as you're finished." And with that Hugh darted off to the place were Ruxton and Bob were busy among the fallen tents.

Here was a wild scene of flapping canvas, which was bobbing up and down in great waves, reminding one of the imitation sea they sometimes have at the theatre. From the midst of it, too, proceeded a hoarse roaring which was not unlike the sound of imitation breakers.

At intervals a head or a leg would wriggle from out the jumble, only, however, to be pounced upon as soon as it appeared, and to have a noose slipped over it by one or other of the watchful victors.

Two figures were already lying on one side, trussed up like fowls. Two more were being operated on as Hugh joined them.

He glanced about and made a rapid calculation.

"Good! I see you've accounted for four—and two are six," said he. "So there must be three more underneath the wreck."

"Only three, sir?" quoth Bob. "Ratlines an' bobstays! They be makin' noise enuff fur a baker's dozen."

Plenty of short coils of rope had been provided by the foresight of the planners of the coup, after they had loosened all the outside guys of the tents, and opened some of the packages of tobacco by way of baiting the trap. It had been Ruxton's idea. It had occurred to him when he had gone to get the pistols, and he had begun the good work then, thinking the scheme might come in handy if they failed in repulsing the first rush. The final arrangements had been completed in the interval between the two last attacks.

Mike came to the assistance of the binders, and helped to drag out and secure the last of the prisoners. It was not all accomplished, of course, without some scuffles, and the captors received some fierce kicks, and even one or two slashes from the knives with which the trapped ruffians were trying to cut their way out. But hampered as the latter were by the folds of stout canvas which had fallen on them—in some cases two or three deep—they could not make much of a fight.

In due time they were all bound, and then they were carried out and laid on the terrace in a row. There they were left while the victors proceeded to re-erect the tents.

This finished, they held a council.

"What's to be done with 'em now?" asked Hugh. "We can't leave 'em lying here all night. They'd freeze to death."

"We must put the beggars into sleeping bags, I suppose," said Ruxton.

"But how? Where are they to come from? We've only got what we'll want ourselves, and—"

"We'll have to go down to their camp and fetch their own for 'em," Ruxton advised. "There can only be five or six of the gentry, at the outside, left there now, and we know that three of 'em are hors de combat. I don't suppose they'll show fight again. But whether they do or not, we'll have to get the bags all the same. They're a lot of rotters, but as you say, we can't let any of 'em freeze to death."

"Right-ho! That's a good idea. We'll leave Mike here, in charge, to see that none of 'em wriggles free. Three of us'll be enough to deal with their pals."

They had first, however, to clear away the barricade at the top of the slope, and had just begun to shift the sledges, when Hugh cast a glance in the direction of the camp they were about to visit.

"Jupiter!" he exclaimed. "There's something going on down there! Why, there's a sledge—and—yes, I do believe it's Grimstock's sledge with the ponies! Must have just arrived!"

The other two stared incredulously. But when they looked at No. 3 camp, there, sure enough, they saw a sledge drawn by ponies, and a group of people standing about as if newly arrived.

"I fancy I can see Grimstock himself," Ruxton muttered. "Now what does this mean? He must have come across from the ship pretty quietly for us to know nothing about it."

"We've been otherwise engaged," Hugh reminded him.

"Yes; but still, it's funny we shouldn't have seen him crossing the ice. And what brings him here at all at this time of night?"

"You can ask him that when we get there—if you care to," Hugh returned tersely. "Come on! Let's get down and see what's going on."

They set out forthwith, and as they drew near the camp, the man they had been speaking of—the actual leader of the expedition—came forward to meet them.

A somewhat curious character, or, rather, mixture of characters, was Mr. Bernard Grimstock. That he was an experienced traveller and explorer, and that he had some repute in scientific circles, was certain. It was known that this was the fourth expedition in search of the elusive North Pole, in which he had been engaged, and it was also known that he had made journeys into other previously unexplored regions, portions of the Congo territory, and other parts of Africa, among them. He had read papers before learned societies, and had lectured to geographical associations, both in England and abroad, and he had made something of a name for himself as an authority in such matters.

Also, it was generally allowed that he was bold and determined, and personally well-fitted for such work. Of commanding physique, indomitable will, hard as nails, well able to bear privation and exposure, he had survived hardships and dangers that had killed off many of his companions and followers in the expeditions in which he had taken part. Yet, with all this in his favour, it cannot exactly be said that he was held in general esteem. Rumours and whispers had been heard as to certain dubious occurrences in which he had been mixed up, and in which, it was hinted, he had played a part that would not be to his credit had the true facts gained publicity

From one ill-fated Arctic journey he had come back almost the only survivor, and his account of the disasters that had overtaken his companions was not everywhere received without suspicion.

As to the rest, it was admitted that he was a capable leader, if somewhat of a martinet, and that he had that kind of talent which seems to be the special gift of such men—the faculty of choosing people to serve under him who possessed just those qualifications best suited to his purpose.

As he looked at the three who were now approaching his face was hard-set and lowering, and there was a flash in his keen eyes as his glance fell upon his two lieutenants, Hugh and Ruxton.

"WELL, gentlemen," began Grimstock, and his voice was harsh and grating. "What is the meaning of this?"

"Of what?" asked Ruxton, who felt himself more particularly singled out.

"Of what? You ask me? I am told that you have ill-treated these men here. That they came to our camp, of which you were in charge, wishing to know if we had a little tobacco to barter or sell, and that you set upon them, and ruthlessly assaulted, not only them, but others as well, who went out from here to the assistance of their comrades."

Ruxton gave a gasp, while Hugh muttered something under his breath which might have been, "Good gracious!"—only, it wasn't.

"They said that, did they—just that?" Ruxton asked.

"Come, sir, don't beat about the bush," said Grimstock, with ominous coldness. "I want to know what it all means. Why have you behaved in a manner which, as you must know, is likely to get us a bad name amongst those people, and turn those who might have been useful allies into possible enemies?"

"I can answer that question," Hugh burst in.

"I didn't ask you, Mr. Arnold. I asked Mr. Ruxton. I suppose he can answer for himself."

"I've no doubt he can—and will—but he's not going to answer for me," said Hugh hotly. He was stung by his leader's tone, and indignant at the manner in which Ruxton was being dealt with. "I am as much in this thing as he is," he went on, "and I wish to say at once that you seem to have been told a pack of lies. These men are no such milk-and-watery innocents as you appear to think. They're, a lot of half-drunken rowdies, who made a descent on the camp while our backs were turned, and—"

"How do you know that, if your backs were turned? And why were they turned? I left you in charge. Why did you leave the camp unguarded?"

"We did not, Mr. Grimstock," Ruxton put in quietly, though he had some difficulty in restraining himself. "We were both there at the time; we were merely walking up and down. It is true that, as Mr. Arnold puts it, our backs were turned for the moment. When we looked round we saw two of these peaceful would-be traders, as you seem to consider them, attacking our two men, and four others walking off with sundry packages under their arms. Of course, we interfered—"

"What do you mean by 'our two men'?" interrupted Grimstock. "You were quite a dozen altogether. It doesn't seem very likely that two or three strangers would attack a camp guarded by a dozen people."

"The others were down yonder, at the Eskimo camp, and there they stuck, and, for the matter of that, there they are now, so there were only two with us at the moment the thieving rascals put in an appearance."

"Ah! Now we're getting at it. And why, pray, did you allow your men to be absent at the Eskimo camp, instead of attending to their duties with you, and looking after my property?"

"Because I couldn't get 'em away," returned Ruxton. "You know what men are, Mr. Grimstock, when they first get ashore after a long bout on board ship. I could do nothing with the beggars, and I almost doubt if you could, either, if you had been there," he added doggedly.

"That's a nice confession to make, Mr. Ruxton," commented the leader, still in the same cold steely tones. "I should be rather ashamed of it if I were in your place. It's as much as to admit that you are not a fit person to be placed in charge of men."

Ruxton started and flushed, and was evidently about to make some warm rejoinder, when Hugh again intervened.

"One moment, Mr. Grimstock," he said, forcing himself to speak calmly. "The important question at this moment is not how these things came about, but what you are going to do with the rioters. Whether we have been to blame is a matter we can discuss afterwards. The thing, just now is that, rightly or wrongly, we thought we were defending your goods, and I may say our goods, for some of 'em, at any rate, as you know, are my property as much as yours, and in doing so, we have had to fight almost for our lives. Fortunately, we came out on top; and if you'll take the trouble to go up to our camp, you'll fine nine of 'em laid out there, tied hand and foot. The question is what are you going to do with them? While we're standing arguing here they may be getting frost-bitten. We came to see if we could get their sleeping bags to put them in for the night. If you choose to let them loose instead, you can do so, but situated as we were—only four of us—we dared not do it."

Grimstock, who had hitherto kept his gaze fixed chiefly on Ruxton, turned it sharply on Hugh in very evident surprise. There was that in the young fellow's manner, to say nothing of the firm, resolute tones in which he had spoken, which was altogether new to him. Up to this time, Hugh had never shown such an independent spirit, but had always seemed to defer to him as the undisputed leader and master of the expedition.

But whatever his real thoughts may have been, Grimstock gave no indication of them, beyond that one quick glance. He seemed to reflect for a moment or two, and then, as though getting the better of his momentary ill-humour, he said:

"Well, if that be the case, we must, as you say, Mr. Arnold, see to them at once. And if you really had to fight a rowdy gang with the odds of a dozen to four against you, I don't see that you can be blamed much if you used them rather roughly. Certainly, I'm not here to champion the cause of a lot of drunken ruffians, if that's what they were. Only, you see, these chaps here preached a very different tale to me—showed me their bruises, and all that; one fellow swears you pushed a sledge on top of him and broke his arm. But it isn't what I think about it; it's what their skipper will think if they preach the same tale to him. It seems to me it will be a question of their word against yours. Well, now—"

"What's all that row?" asked Ruxton suddenly.

A noise of barking dogs, mingled with shouts and the cracking of whips, had become audible. Faintly borne at first on the clear, keen air, it was rapidly growing louder.

"Somebody coming," said Hugh, after listening for a moment. "Dogs—sledge. More natives, I suppose."

"No: they're driving too fast for Eskimos," Ruxton declared.

"Besides, those are not natives' shouts, nor," he added, with a short laugh, "native curses. Nobody but a dare-devil white man, one three sheets in the wind, probably, would drive like that by night."

"Then it must be McClinter!" said Grimstock. "At least—er—I heard the men here say they were expecting their skipper, and that is his name."

Ruxton and Hugh both opened their eyes. It was passing strange that their leader should have the name so pat, and they made mental note of the fact, and also of the rather lame manner in which he tried to account for his knowledge.

A few minutes later the sledge arrived, drawn by a team of large Eskimo dogs. It was driven at a reckless speed by a skin-clad figure, flourishing a long whip, which he kept cracking to an accompaniment of shouts, oaths, and snatches of song.

He pulled up suddenly—so suddenly, that another skin-clad figure beside him, who seemed to have been dozing, swung forward and rolled off his seat into the snow.

As the driver threw the reins loose, the dogs started on again, and would have pulled the heavy sledge over the fallen man, if Hugh had not dashed forward and dragged him clear.

"Hallo, Grimstock!" roared out the driver to Hugh. "Mon, I know I'm behind time. Dinna ye fash yersel' about yon sleepy chiel. A mickle bumping'll help t' wake up. Eh? What? Who the deil are you, mon?"

He had suddenly found out that he had been mistaking a stranger for Grimstock. The latter now came up.

"Come this way," he said, taking him by the arm, and leading him out of earshot.

Meantime, Hugh and Ruxton helped to put "the sleepy chiel" on his legs. He turned out, as they afterwards knew, to be McClinter's mate, a rough, surly fellow, who had the appearance of one who had not quite slept off his last debauch.

His first act, when he was completely roused, was to catch up the long whip the skipper had dropped, and set about an Eskimo attendant who had been seated at the back. He blamed him, with much fierce language, poured forth in broken English, for not having been quick enough in going to take charge of the dogs.

Hugh and Ruxton looked at one another and drew back in disgust.

"Nice company we've drifted into," muttered Ruxton, in a low tone. "Skipper and crew are evidently much of a kidney. That doesn't surprise me—I expected it. But what does surprise me is the clear evidence we have here that Grimstock is on friendly terms with such gentry."

"Yes; the skipper had his name as pat as Grimstock had his," returned Hugh, in tones equally guarded. "I confess I don't understand it."

"You will—later on—or I'm a Dutchman," was the enigmatic reply, and just then their leader and his companion came back.

"Our friend here will accompany us to the camp and set his men free himself," Grimstock explained.

"Ye're comin' wi' us, ye ken, Landshutt," said the skipper to his mate, "and bring ma' whip wi' ye—an' yer ain, too."

"He's going to set 'em free himself, is he?" Ruxton whispered to Hugh. "Yes, and in his own fashion, too, I reckon. Well! The beggars deserve no mercy. They'd have smashed us up in their drunken fury if we hadn't been too much for 'em. I, for one, sha'n't feel any sympathy for 'em if they get it hot."

And, as a matter of fact, they did get it pretty hot. McClinter and his mate cut their bonds and set them on their feet, one after the other, and then laid their whips about them in no playful fashion. The men, on their part, made neither resistance nor remonstrance, but accepted it all as though it had been an ordinary part of the day's routine, and slunk back to their camp like whipped hounds.

Then, Grimstock went off to the Eskimo camp to round up his own recalcitrant followers, and the skipper and his man accompanied him there also. Whether the whips were used there, in like manner, neither Hugh nor Ruxton knew, for they remained at their own camp, putting things straight, and making preparations for a night's rest.

Presently, the missing men came dropping in by twos and threes, some looking sheepish, some roaring out in noisy chorus, most of them walking unsteadily. They stumbled into the tents set apart for them, scrambled somehow into their sleeping bags, and lay down.

"I'm going back to the ship," said Grimstock, shortly, when he had seen them all into their quarters. "I shall expect to see you two gentlemen there an hour or so before sunrise, so as to get everything ready for landing more stores as soon as it's light enough."

And with that he and his two strange companions went off together.

Hugh and Ruxton had a tent to themselves, and they were not long before they turned in.

"Well," said the latter, before going to sleep, "this is our first night ashore on the little trip that was to bring everybody engaged in it fame, and honours, and so on. What do you think of it?"

"I don't know what to think. I'm both surprised and puzzled. Putting aside, the scrimmage, who are these people? Who is McClinter? What's he doing here? How came Grimstock to know he was here? And why did he come to meet him in this queer, clandestine sort of way?"

But Ruxton did not attempt to answer these questions. He only gave a short, grim laugh.

"I fancy you'll meet with a good deal more that will both surprise and puzzle you before we're many weeks older, or I'm a Dutchman," he said. And with that he turned over and fell asleep.

AFTER a few hours' sleep, Hugh and Ruxton woke up, scrambled out of their sleeping bags, and called the two sailors. These, in turn, roused up the other men, who, still sleepy and half-dazed after the "feasting" in which they had indulged overnight, turned out in ill-humour, grumbling and discontented at being called so soon.

The moon had disappeared, and it would have been very dark had it not been that the sky was lighted up by the Northern Lights, which threw a weird, lurid, fitful sort of twilight over the desolate landscape.

Bob Cable and a couple of men went off to the Eskimo camp to bring back the teams of dogs, which had been taken there the previous evening to be fed and spend the night.

Presently, a noise of much barking, cracking of whips, and shouts in a strange tongue announced that they were on the move, and a little later the teams appeared. They were in charge of a dozen Eskimos, who proceeded to harness them to the sledges which had come in so handy for purposes of defence in the early part of the night.

Then, the whole party, save a couple of men who were left in charge of the tents, moved off through the strange, dim light, and proceeded across the ice to the distant ship.

There they found Grimstock already at work with the crew of his vessel, and the new-comers joined in the necessary preparations for landing further stores.

The morning was fine, and when the sun made its tardy appearance, it rose in an almost cloudless sky, shining cheerfully upon a busy scene. There were the sounds of the clanking capstans and rattling chains, the chanting songs of the sailors, the noise and bustle of shifting heavy cargo and hoisting it into the steam pinnace lying alongside. This travelled to and fro between the ship and the landing place, puffing and coughing, churning up the dark waters, and bumping its way through masses of floating ice.

The stores included half a dozen large motor-sledges—novelties which excited no small amount of curiosity and astonishment among the aborigines, who had never in their wildest dreams imagined such a method of travelling over their snowy land.

They were, indeed, almost as much a novelty to the white men themselves as to the natives, for though similar machines had been tried with success amid the snows of Norway, this was the first time they had been seen on the ice-fields of the Far North. Much curiosity, therefore, was felt as to how the experiment was likely to turn out.

"It's evident the dogs don't approve of 'em," laughed Hugh. "Just see how disgusted they look! It offends their dignity to have to play second fiddle to such un-doglike monstrosities."

Not only the dogs, but their native masters, looked askance at this newfangled method of travelling. Dog-sledges had been good enough for them and for their ancestors from time immemorial. But as to these queer contrivances, which went by themselves and required neither whips to urge them, nor "pemmican," or other food to eat, they knew not what to think. They regarded them with mingled awe and fear, and forthwith dubbed them by a name which was the naive equivalent for "devil-sled."

Now, Val Ruxton had been trained as an engineer, and Grimstock had consulted him at the time the expedition was being organised, as to the advisability of adopting these new devices. He had assisted at their trial tests before leaving England, hence, he felt a special interest in them now, and had arranged to drive the first one himself.

As the dogs had so unmistakably evinced their disapproval of the new arrivals, it was deemed better to let them go on first with their own drivers.

As soon, therefore, as a couple of dog-sledges had loaded up, they drove off, and a little later, Ruxton, with Hugh beside him, took his seat on one of the motor-sledges and started in their wake.

The motor, besides carrying a heavy load of its own, was towing two loaded dog-sledges, in charge of Mike and Bob. These two sailors, it should be mentioned, had been picked out by Grimstock's lieutenants to attend specially on them. Hence, their present post of honour, which made them the envy of the rest of the crew, who, with Grimstock himself, were watching the performance of the machine.

The start-off was a splendid success. The motor quickly showed that it thought nothing of its loads, and was not afraid of the slippery ice. Away it went, drawing with ease the smaller sleds behind it. Panting, whirring, amid a chorus of cheers, it glided over the frozen surface at a rate which showed at once that it would very quickly overtake the teams of dogs in front of it.

Gradually the speed increased, but with it the humming increased also, till it grew into a loud, unearthly wail. Soon this reached the ears of the dogs, and inspired them with a desire to stop and turn round to see what kind of monster it was that was pressing them.

"I say! Isn't this glorious!" cried Val. "It's a bit of an eye-opener, you know! Why, we shall be able to reach the Pole in no time if we can travel there, in this style!"

"Yes, if our stock of petrol doesn't give out," Hugh assented. "But how about those johnnies in front of us? I'm afraid we're scaring those dogs out of their lives. Perhaps we'd better stop for a few minutes, and give the drivers a chance to get their teams in hand."

Ruxton saw the force of this and drew up; but not without a protest.

"Humph! We sha'n't gain much, after all, if we're going to have all this fuss every time," he grumbled. "Why don't the stupid drivers clear off to one side, and give us a chance to get on ahead?"

"They seem to have come to the conclusion that that is their best plan," observed Hugh. "I can see that they're trying to do it."

Amid much shouting and cracking of whips, the Eskimos effected this manoeuvre, and managed to drive their unruly animals off to the right, leaving the track clear for the motor.

"Thank goodness for that," muttered Ruxton. "Now we'll go past in style, and show 'em what we can do!"

Forgetting the sleds he was towing, he started forward too quickly. There was a jerk, the towing-line snapped, and the motor-sledge flew forward at full speed. Then, with that erratic freakishness which motors so often exhibit as part of their nature, it suddenly became unmanageable, and dashed off to the right towards the barking dogs, as though determined to punish them for their impertinence.

Another moment and it would have been amongst them; but the panic-stricken animals, now completely out of hand, started off in their turn, and galloped for their lives, heading straight for a wide lead in the ice.

The driver of one team somehow succeeded in turning his pack, and raced past the end of the fissure; but the second one was less skilful or less lucky, and the whole plunged into the water, the sledge carrying its unfortunate driver with it.

Ruxton, meantime, had managed to bring the motor to its senses—and a standstill; and springing down he and Hugh ran forward to the edge of the water.

There they saw the dogs swimming about, doing their best to keep their heads above water, but still held by the harness to the submerged sledge; which fact showed that it could not be very deep there. Of the driver nothing could be seen.

Without a moment's hesitation Hugh dived into the ice-cold water. It was even shallower than he expected, and the first thing he did was to dash his head against the sledge which was lying on the bottom. The knock was a nasty one; but paying no attention to it he began groping about till he grasped the man he was after; only, however, to find that he was pinned down under the sledge.

Rising to the surface for a fresh gasp of air, he turned over like a porpoise, and plunged downward again in such a way as to get his feet on the bottom. Then he got both hands under one side of the sledge, and with a mighty effort, raised the whole affair sufficiently to enable him to get the driver clear. A moment later he regained the surface with him.

Here he found himself in fresh difficulties. He came up in the midst of the crowd of struggling dogs, and some of them resented his intrusion amongst them and began to attack him viciously.

Hampered as he was by the dead weight of the one he had rescued—the man was unconscious—Hugh found himself in a very tight corner. He could not hold up the man and fight off the dogs as well; but he was not going to let go. Then an idea occurred to him.

He seized one of the dogs nearest to him from behind by the harness in such a way as to make him, whether he wished to or not, assist him in supporting his burden with one arm, and while doing that he beat off the rest of the dogs as well as he could with the other.

There was a whizzing sound, something hurtled through the air, and a noose fell over his head. It was a rope which Ruxton had thrown, and Hugh slipped an arm through it.

Then there came a tug on the line, and he was drawn towards the edge of the ice. As the dogs were tethered to the sledge they were quickly left behind, and he released his hold of the one he had seized. A moment or two later he and his burden were hauled onto the ice.

Eskimos are pretty well used to an occasional plunge into the icy water of their seas. They meet with many such little incidents in the course of the hunts after seal and walrus, and this one soon came to and seemed none the worse for the experience.

Hugh himself was nearly exhausted, but after a pull at a flask which his friend produced, he began to pick up.

The whole adventure had been witnessed from the ship, and a party, consisting partly of sailors and partly of natives, presently arrived, and set to work to recover first the dogs and then the sunken sledge.

Meantime, the rescued Eskimo, a rather good-looking man for one of his race, was volubly pouring out his thanks, though, as he spoke in his native tongue, Hugh did not understand a word he said. Ruxton, however, who had been amongst these people before, and could speak the language a little, was able to interpret.

"He is telling you how grateful he is," he explained. "He is telling you his name, and a good part of his family history. He is called Lybendo, and he is particularly anxious that you should remember the fact. I suppose he is someone of importance amongst his own people. He also is filled with wonder and admiration at the prowess you displayed. He declares it would have taken two ordinary men to have lifted the loaded sledge up and pull him from under it even on dry land—to say nothing of doing it at the bottom of eight or nine feet of water."

Hugh laughed in his usual easy, good-humoured fashion. "Say something nice to him, Val, by way of acknowledging the compliment," he said. "And then, if you've no objection. I'd like to resume our interrupted journey. The sooner we can get to some place where I can get a change the better I shall be pleased. I'm already frozen stiff all over. These Eskimo johnnies may be used to that sort of thing; but to me as yet it feels jolly uncomfortable."

WHEN the motor-sledge reached the camp, those in charge of it found, to their satisfaction, that their rowdy neighbours of the previous night had cleared off, bag and baggage.

"That's a good riddance!" cried Hugh. "Let's hope we've seen the last of 'em."

His friend Val did not share the agreeable expectation which this wish implied, and later on they found that he was right.

During the rest of the day many more journeys were made, all being successfully and quickly carried out. The motor-sledges were on their best behaviour, and accomplished even more than had been hoped from them.

"Ah!" said Hugh, "you did well, Val, in advising Grimstock to bring them. As they cost a lot of money, it's jolly satisfactory to think that it's been so well laid out. With such an equipment as we've now got, and our splendid lot of stores, what is there—bar accidents—to prevent our reaching the Pole?"

"Yes; our outfit's all right enough. It's the human element which is the doubtful part," returned Ruxton. With which somewhat dark saying he turned from the subject in a way which showed he did not wish to pursue it further.

After one of these trips they returned to the Petrel to find a surprise awaiting them.

A strange vessel was seen in the distance heading in their direction. In due time she ran in and lay-to a short distance off, and it became known that she was a whaler called the Hawk.

A boat was lowered and rowed towards the Petrel. In the stern sat McClinter, and the men rowing were recognised by the two friends as some of the gang who had attacked the camp the night before.

Val looked at Hugh, and as their eyes met he gave a low whistle.

"What did I tell you?" he muttered.

McClinter climbed on board and was taken by Grimstock down into his cabin, where the two remained in close talk.

Hugh, meantime, started off with a motor-load by himself to the camp, where he remained sorting and arranging the stores. Thus it happened that it was not until the evening, when the day's work was at an end, that the two had another chance to compare notes.

"Well! Let's hope we shall have a quieter time than we had last night," Hugh observed, as he lighted his pipe after their supper. "What's your idea of things now? Have you learned anything fresh?"

"I've kept my eyes and ears open," was the answer. "Also I had a few words with Grimstock, and with that precious beauty the skipper of the Hawk."

"A few words!" repealed Hugh. "Do you mean that there was another row?"

"Oh, no. They were both as civil as sand-boys. Butter wouldn't melt in their mouths, bless you! McClinter actually apologised, after a fashion of his own, for the behaviour of his men. Said we'd given 'em something to remember us by, and he was glad of it. They deserved it—and so on. And Grimstock cried ditto. But I'm not to be taken in that way. I saw through their blarney—as I did last night."

Hugh laughed; but on this occasion there was evidently not much mirth in his laughter. He had rather the air of one trying to appear more indifferent than he really felt.

"What a suspicious, unbelieving beggar you are, Ruxton!" he said.

The other glanced keenly at him, but remained silent for a space, as though turning something over in his mind. Then he spoke again.

"I told you last night that I had no wish to seem to pry into your affairs; and I haven't now. But you said something to Grimstock which surprised me pretty considerably."

Hugh gave another uneasy laugh.

"I think I can guess what it is you're driving at," he replied. "I suppose it's what I said about the stores being partly mine?"

"You've hit it. You said they were as much yours as Grimstock's—or words to that effect. I needn't ask you if it is true. You wouldn't have said it if it hadn't been, and most certainly Grimstock would not have let it pass without denial. But he did not deny it—I noticed that. Also, your blurting it out didn't at all please him, for he shot a most evil glance at you—I noticed that, too. Yet the next moment he threw off his insolent, bullying tone, and cooed as gently as any sucking dove. I noticed that, too. Now, what does it all mean?"

"Well, what I said was true enough, Ruxton, though I felt sorry directly after that I had—as you put it—blurted it out. You've used just the right word, though—it was blurted out on the impulse of the moment, because I felt savage and indignant at his manner. I paid a large share of the cost of fitting out this expedition."

"Humph! Are you then a millionaire in disguise?" Hugh shook his head.

"No more than yourself," he declared gravely. "The amount I paid represents practically all I and my mother—who is a widow with only myself to support her—had to live on. Unless this journey turns out a success in one way or another, I and she will be practically beggars,"

"But—Whatever then made you—No, old chap; I beg your pardon! I said I didn't want to pry into your affairs; and here, hang me if I'm not doing it! I don't want to know any more until—if ever that time should come—you wish to tell me of your own accord. I couldn't help seeing, however, that Grimstock was pretty riled at your saying it."

"Why, yes; and he has some reason to be, because it was expressly arranged that that part of the affair was to be regarded as private and confidential. And now—confound it!—I've referred to it before you, and in doing so have broken the promise I made him."

"Humph! I don't see, all the same, that he need have looked so evilly at you over it. For the matter of that, he's only himself to thank for it. Besides—what harm have you done? It won't go any farther; I shall regard it as 'private and confidential' as you call it."

"Thank you. Yes; I felt I could rely on you as to that, or else I should have felt more concerned about it than I have done."

"I wish that were all there is to trouble about," muttered Ruxton, rather as though to himself than to his companion.

"Why—what other burden have you lying heavily on your soul?"

Ruxton looked very straight at his friend, and said slowly:

"I am not going to tell you all that is in my mind. I think perhaps it is better not to—at present. But I'm going to give you a warning—you can pay attention to it or not, as you think proper. It is this: Don't trust Grimstock, or that skipper fellow. They're a good pair to run in double harness, these two—and don't you forget it! Keep your eyes skinned, and keep on the safe side with those johnnies. There, now! I've got it out! And if you don't profit by what I've said it will be your own fault, not mine. Hullo! Here comes one of the—Why, it's the old Eskimo, Amaki, himself. I wonder what he wants? By the way, you haven't seen him yet, have you?"

"No; I remember hearing the name. You spoke of him last night."

"Yes; well, he's a most interesting old joker, once you get used to the atmosphere of cart-wheel grease and stale fish-glue which he carries about with him."

Turning to the one he had been talking of, who had now come within speaking distance, Ruxton said something in the Eskimo tongue.

The new-comer replied, and there was some talk between the two, which Ruxton interpreted.

"Amaki has made a rather funny request," he explained. "He says, so far as I can make out, that some more people have come to his camp, and there is not much room. Will we allow him to sleep here to-night? That's the gist of what he says; but I confess I don't quite understand it. They must be precious crowded if they can't find room for the old chap, especially as he is a sort of chief, or patriarch, or whatever it is amongst them. However, his reasons don't concern us. I think the old joker is all right. So I guess we can let him squeeze in amongst our people, eh?"

"Oh, yes; if he wants to, I suppose. Well, my dainty, tallow-eating friend, what the dickens are you staring at me like, that for?"

This polite inquiry was addressed to the Eskimo, who had fixes his eager glance on the speaker, as though he were trying to read his very thoughts.

"You—you—English—English man?" he said, in curious broken English.

"I suppose so—some animal of that species," returned Hugh, highly amused. "What's up, old greaser?"

The Eskimo seemed somehow greatly moved. He worked his arms about, shook his head, muttered to himself, and ended by producing something from under his clothes, gabbling volubly to Ruxton the while.

"Hullo! Now this is very curious—and interesting, exclaimed Val.

"It seems that Lybendo, the chap von fished out of the water to-day, is this old joker's son. I told you I thought he was someone of importance among his own folk. Amaki is very, very grateful to you, he says; and as a slight mark of his gratitude he has brought you a little present which he begs you will accept."

As he spoke Ruxton put out a hand to take the proffered present, but the Eskimo snatched it back, and offered it again politely to Hugh.

The latter, on his part, started, and seemed scarcely less moved than the Eskimo himself.