RGL e-Book Cover 2017¸

RGL e-Book Cover 2017¸

"The Black Opal," John F. Shaw & Co., London, London, 1914

Frontispiece

The figure of an old man with long white hair and a beard.

"Well, here I am, Lorry! Now tell me what on earth is the meaning of your mysterious message! Why, man, how serious you look! What's up? Anything wrong?"

Thus spoke, or rather shouted, Ralph Playfair, a tall, muscular youth, with a bright, good-looking face, and merry eyes, as he came bursting in upon his chum. Even while speaking his eager eyes roved about scrutinising everything around, as if he thought he might gather some notion of what was "up" by scanning the furniture.

The one addressed as Lorry was also tall and athletic-looking, with a handsome face and a splendid figure. The two young fellows had been at school together, where they had left behind them "records" in athletics, by the performance of feats which were likely to live as traditions in the school so long as it remained in existence.

Lorry, though a little taller, appeared to be rather the younger of the two. He was a veritable young giant; darker in complexion, and somewhat more thoughtful in manner than his volatile, high-spirited friend. But if Ralph was slightly less in height he was broader and sturdier in build, and looked, with his fair, curling hair and laughing eyes, a typical Britisher.

"To-morrow, Ralph," said Lorry, stretching his muscular arms, and taking a deep breath, "to-morrow I shall be twenty years of age—so I'm given to understand, and——"

"Is that all—why you might have told me that in your letter without bringing me all this way! Well, good-bye. I'm awfully pleased to hear it, and, maybe, to-morrow I'll look in again."

"And to-day," continued Lorry, disregarding the interruption, "Captain Woodham, my dear, kind, foster-father, has promised to tell me my own history—who I am, what I am, and where I came from—of which, as you are aware, I've known no more than the man in the moon.

"Further, the Captain has intimated to me that I shall have to make up my mind about a very important matter—to come to a momentous decision about something or other. So, as you are the best friend I have in the world—next to him—I asked permission for you to be present to hear the wonderful communication—for wonderful I understand it is really to be. The hints he has already let drop are enough to rouse the curiosity and fire the imagination of even a wooden image were they whispered into its wooden ears. Now, will you stay, or are you still in such a hurry to be off?"

"I'll stay, you bet! And I guess I shan't have to wait long, for here comes the Captain himself, and I can see he's bursting with the secret. See how tight his reefer looks on him to-day!"

As Ralph spoke, a big, burly figure, with the unmistakable rolling gait of a seaman, passed the window of the little cottage by the sea where this conversation took place. They heard the outer door open and shut, and a moment later Captain Woodham strode into the room.

He stood for a moment in the doorway looking at the two without speaking. He was almost Herculean in build; his form filled up the whole doorway, and he had to stoop as he came through it. In manner he was bluff, but hearty and honest-looking, and though his seamed and weather-beaten complexion and grizzled hair and beard made his face, when in repose, appear hard and stern, yet, when he spoke, his eyes would often twinkle with a light that was half-kindly, half-humorous.

"Ah! So you're here, Ralph," he said, and he extended his hand and took that of the visitor in a grasp which made even that young athlete wince. "You've come to hear the yarn I've promised to tell to-day, eh? Well, first, give me your promise that you'll regard it as a sacred confidence about which you're never to breathe a word to a living soul without permission. Then give me time to light my pipe, and I'm ready."

Ralph gave the assurance required and presently, when the three were seated round the table, the Captain started his pipe, took a few preliminary puffs, gazing thoughtfully the while through the window out over the sea, where the afternoon sun was nearing the horizon, and began his promised "yarn":

"It had been just such an afternoon as this—only far hotter, with a more fiery sky—that I lay becalmed in my ship, the Foam, in the Caribbean Sea—or rather upon the outer edge of what is known as the Sea of Sargasso—that is 'Sargasso Weed.' I don't suppose you youngsters know where that is. In school geographies they don't say much about it—"

"I've heard of it," Ralph put in. "An old sailor once told me something about it. He said that it is a most strange, mysterious region, a vast, desolate expanse——"

"Desolate! It's the most desolate spot on earth," broke in the Captain, bringing his fist down on the table to emphasise his words, "unless, perhaps, it may be the Polar regions—and as to its being mysterious—well, wait till ye've heard my story, then ye'll allow there's mystery enough to make a dozen ordinary sea yarns sound weak and commonplace by comparison.

"I'd been trading among the West Indian Islands, but had met with bad luck, and consequently I wasn't in a very good temper when the wind fell light and I found myself drifting about just outside that dreary waste of Sargasso Weed."

"Tell me what it's like," Lorry asked. "I don't quite understand."

"It's a tract," the Captain proceeded to explain, "many thousands of square miles in extent, where the sea appears to be, for the most part, comparatively shallow, and it is everywhere covered with a tangled mass of Sargasso weed brought down originally by the well-known Gulf Stream. No doubt there are rocks just under water, or, maybe, just awash in places, to which the weed clings. But you can't tell what is there or what isn't, really, because the weed is so thick, nobody can go far into it to see. You can't get very far beyond the outer edge or fringe. People who have tried to penetrate into it have got stuck fast and nearly lost their lives. Precious glad they were—and precious lucky too—if they managed to struggle back to open water again."

"Then," said Lorry thoughtfully, "no one can tell what there may be in the middle of this great tract?"

"Precisely," was the Captain's answer, and as he spoke he looked hard and curiously at the young man. "There may be inhabited land there," he continued slowly, "for anything that the rest of the world can tell. For all that our geographers know, there may be a thriving country hidden away in its midst, filled with the survivors of some ancient, long-forgotten race, who, through the slow accumulation of weed brought down by the great Gulf Stream during successive ages, may have been cut off from all communication with the outer world for a thousand years or longer."

"By Jove! What a fascinating idea!" exclaimed Ralph, his eyes lighting up with enthusiasm. "What a wonderful field it opens up to the imagination! What a chance for some fortunate explorer!"

"Ye're right there, lad, it is so," returned Captain Woodham with the same slow manner and curious look. "Is it the sort of adventure that would tempt you, d'ye think, if it were shown that there was any reasonable ground for suspecting the existence of such a country at the present day?"

There was no hesitation in giving a reply to this query, and no doubt as to its sincerity. The two listeners were as one, and declared they would only be too delighted to meet with any chance of joining in such an adventure.

The Captain eyed them both keenly, but made no comment; and resumed his narrative:

"It was after a very hot day, as I have said, that I found my vessel drifting almost without enough wind to give us steerage-way upon the very verge of this vast sea of weed. As the sun set, a mist had closed in upon us; but presently the moon rose. It was nearly full, and was gloriously brilliant, shining with a splendour that one finds only in the tropics. Then the mist cleared away almost entirely, and I saw before me a wide, open channel stretching right away up into the expanse of weed till it was lost in the haze which still hung over the extreme distance.

"Now this in itself was a remarkable discovery; for no sailor or navigator knew of such a channel or had heard of such a thing, so far as I was aware. But there was something yet more surprising to come.

"The night had become one of the most beautiful I ever remembered. Save, as I have said, for the distant horizon, everything was exceptionally clear. The moon hung above, poised in a cloudless sky of deepest blue, and shone straight down the strange channel, from which its bright rays were reflected as from burnished glass. Looking through my glasses I could make out distinctly numbers of the vessels which are at all times to be seen entangled in the weed. They are derelicts, for the most part, which have been abandoned at sea, and which, after perhaps years of lonely drifting, find here their final resting-place. Scientists account for this by telling us that the whole Atlantic Ocean is revolving slowly round and round, like a gigantic whirlpool, of which the Sea of Sargasso is the centre. Hence, numbers of vessels which have been abandoned hundreds—thousands—of miles away, if they should fail to sink at sea, are drifted, sooner or later, into this centre, and once there the weed seizes on 'em and holds 'em fast. And, strange to say, when there they do not seem to rot and go to pieces as they would elsewhere. Some suppose that the weed impregnates the water with some preservative principle; and no doubt, in any case, it lays hold of the timbers and binds 'em, and so helps to preserve the hulks. Also, where the weed is no waves can break, or foam and tumble; and in a general way there is not much wind. It is a region of calms and fogs and desolation, and there are no forces at work to aid in the break-up of these derelicts. So there they are, by the hundred, and by the thousand, some of 'em of very ancient build and rig; so that it is quite possible to believe there may be some foundation for the yarns which declare that old Spanish galleons are still to be met with there, laden with gold and treasure, if one could only get at them.

"Well, all the old yarns of this character that I had ever heard came crowding into my mind as I stood on the deck staring in stupid wonder at the long, clear strip of open water running right into the midst of the weed. Here, I thought to myself, is a means of testing some of these old legends. It might be worth while to get a boat out and row up yonder channel and investigate.

"And then, while I gazed and marvelled, there came into view, in the distance, a dark speck floating down the channel towards the sea, evidently drifting upon a current which was flowing in our direction.

"By degrees the speck increased in size, and I watched it through my glasses with intense curiosity, for it seemed to me that it was gradually assuming the shape of one of those ancient war-galleys of past ages of which one sees pictures in books.

"As it came nearer, this curious idea forced itself more and more upon my mind. I could see that the queer craft had a very high, curved prow, with the open jaws of some terrible monster by way of figure-head. It was battered and war-worn, and yet, somehow, appeared to be still strong and serviceable. Indeed it might very well have belonged to one of the navies of the ancient world when Greeks and Romans fought their sea-battles in vessels of somewhat similar design.

"Slowly, silently, the strange, weird-looking craft drifted on its way. Very uncanny, very ghostly, it seemed, floating there in the bright moonlight; and again there rushed into my mind various wild tales I had heard, at various times, as to the mysterious unknown region from the heart of which this queer, old-world vessel must have somehow escaped.

"Just as I was calculating how long the queer vessel might take to reach the open water where the Foam then was, a puff of wind blowing across the channel drifted it to the side, where it became entangled in a thick mass of weed. It seemed then pretty certain that its voyage was ended, and that if I wished to make closer acquaintance with it, it would be necessary to get out a boat; and I accordingly ordered one to be lowered.

"A few minutes later I was on my way in my gig, with a couple of stout rowers, to overhaul the stranger. So far, there had been nothing to indicate that there was anyone aboard of her; nor did it enter my mind for one moment that there was likely to be. My idea was that she was just a queer old relic of ancient days which had been entangled in the weed, and, after being thus strangely preserved for goodness only knows how many years, she had now somehow accidentally broken loose and drifted down towards the sea. As an antiquarian curiosity, the find might be worth looking at, and even, perhaps, worth securing and taking back to England. But beyond that I had no expectation of meeting with anything to pay for the trouble I was taking.

"In this frame of mind I approached the relic, and I was surprised to find that she was much larger than I had imagined. As we drew alongside I stood up and tried to peer over her side, so high was she out of the water. Finding I could not see much that way, I climbed up; and, without more ado, sprang on board.

"The next moment I had almost jumped hack again but that wonder held me fast; and I remained staring down in horror and astonishment at the scene that was there revealed!"

Captain Woodham paused for a while and remained silent and contemplative, as though the remembrance of the scene he had spoken of had still power to call up some unusual emotion in his mind. His listeners also remained silent, waiting with eager interest for what was to come.

"What I then saw," the narrator presently went on, "was so unexpected, so unaccountable, so utterly bewildering, that even now, at times, I find myself almost wondering whether it really happened or whether the whole affair was not a troubled dream.

"At such times I have to remind myself of the solid proofs of its reality which still exist. They, as you will presently learn, are too tangible, too real, for a doubt to exist in either my own mind or in that of anyone else who may come to know the true facts.

"What I saw, then, was this: I saw that the vessel I had boarded was in very truth a war galley built upon the ancient model. She had two decks, the lower one being for rowers. Lying about on the upper deck were several dead bodies."

"Dead bodies!" cried his hearers in a breath.

"Aye, dead bodies! That sounds queer enough, doesn't it—but queerer still, they were nearly all dressed in armour."

"Armour!" burst from the two eager auditors.

"Yes, armour! Beautiful armour, too! Wonderfully worked and inlaid with gold and silver. One man thus attired had evidently been carrying a banner of a deep red tint, with some device worked upon it in gold. He still clung to this with both hands, and he and his flag had fallen together upon the blood-stained deck. He had been killed by an arrow which had buried itself in his breast.

"There were three other dead bodies, all dressed in armour, and all

bearing evidence that arrows had caused their deaths. One of them was a very

fine, handsome-looking man, quite a giant in stature, and evidently a chief.

His

face was swarthy but by no means dark, and the features were refined and

noble-looking, even in death. He was wearing the richest armour suit of any;

from his shoulders hung a crimson cloak fastened by a diamond clasp

which sparkled and flashed in the moonlight. His sword was of great size and

weight, indicating that he must have been of immense strength, and this, and

a dagger at his belt, were set with precious stones. Beside him was a circlet

or light crown of gold which seemed to have fallen from his head with his

helmet. I picked this up and looked at it. What it was like I will tell you

later—or rather you will see for yourself, Lorry—-"

"See for myself?" Lorry repeated wonderingly. "Why speak of me in particular?"

"You will hear directly. Just as I was handling the crown, I heard a cry as of a little child, and then a groan. Startled at these sounds I looked about and saw yet another prostrate form lying huddled up under a bench. I went to it and turned it over, and found a man dressed very differently to all the others, in a very plain, yet most bizarre costume, principally leather and a sort of coarse canvas. Stooping down, I found that his heart was still beating. At once I tried to move him further out on to the deck so that I might succour him the better, and as I did so I found that he had in his arms what looked like a bundle of wraps. With some difficulty I unclasped his arms and got it away from him. As I gently removed it there was another cry, the bundle unrolled, and disclosed to my astonished and bewildered gaze a little child!"

"Great Scott! What next, I wonder?" Ralph exclaimed.

"I took the child up and examined it; it was very richly dressed, and appeared to be unharmed. I called to my assistance one of the men I had brought with me, and he took the infant while I poured some brandy from my flask into the mouth of the man who was still alive. In a little while he revived sufficiently to be able to open his eyes, but was still too weak to speak. With the help of my men we moved him into my boat, and the child also; and then it was that I noticed certain signs which I knew to be the sure forerunners of one of those storms which, in the tropics, often spring up with unexpected suddenness.

"My two sailors noticed them also, and in spite of their interest in the derelict galley and its ghastly burden, they did not hesitate to urge an immediate return to the ship. The names of these two sailors, by the way, were Dan Oatly and Peter Roff—good, honest, trustworthy fellows, both of them. I mention their names on account of what has occurred since.

"'Theer's a sea mist a-comin' up, Cap'en,' I remember Dan Oatly, one of the two, saying, 'an' if we don't slip back to the ship pretty quick, we'll likely miss her altogether.' The wisdom of his advice was undeniable. Already the wind was beginning to moan over the desolate tract; and I decided, very reluctantly, that we must leave the galley where she was and trust to being able to return to her again when the storm had passed over. She was too heavy for us to attempt to take her in tow in the circumstances; and my gig was too small to take the dead bodies on board. There was nothing to be done, therefore, but leave them for the time where they were. I slipped back, with Dan, to examine them again, to make quite sure they were really dead; and then we rowed off as hard as we could, and only reached our ship in time. A few minutes later We were surrounded by a thick, driving mist, and had to make for the open sea to avoid being blown into the weed by the rising wind.

"The storm which followed proved to be a more serious affair than we had expected; it turned out to be a tempest of a character very unusual in those parts. For days we battled with it; and when finally it passed, and we were able to return to seek for the galley, all trace of it or of the open channel had disappeared, and we found no sign of either. Vainly we cruised about, examined through our glasses all we could see of the expanse of weed, and searched, with the boats, for an inlet. All our efforts failed, and we had at last to give up the quest and come away; and it thus came about that we never set eyes again upon that queer old craft, or its unfortunate occupants.

"Meantime, of the two we had rescued from her—the child and the man—the former throve famously, but the latter never really rallied. He was clearly sinking gradually, and seemed too ill to rouse himself to speak lucidly, though he sometimes mumbled incoherently in a tongue unknown to anyone on board.

"One day, however, there came a change. I could see it directly I went into the cabin where he was lying. I saw the light of reason in his eyes, but I also read there that he was not long for this world. Then came another surprise—he addressed me in English!"

"In English!" exclaimed Ralph. Both the young men had been listening with eager attention, too interested to interrupt the narrator with comments.

"It sounds strange," said the Captain, "and you can understand how astonished I was, but that particular matter was easy of explanation. He was an English sailor, he told me, and his name was Jackson. Some six years previously the ship he had been sailing in had been wrecked in the same neighbourhood as that in which we had found him, and he and his two companions had floated about in an open boat in a thick fog. When the fog cleared they found they had somehow drifted up an open channel which was surrounded on every side by the weed. Not knowing which way to go, they had followed up the channel in the wrong direction, going farther and farther away from the sea, until they came to a large expanse of open water in the very heart of the vast tract of weed. Here they came upon an altogether unknown country, where they met with adventures so strange that I should hesitate to tell you of them if I had not received every reasonable proof of the truth of the statements made to me."

Then followed an account of some of the adventures which had befallen the man Jackson and those with him. The worthy Captain had written them down at length, it seemed, as Jackson had narrated them, and he now showed the manuscript to the two young fellows. It is not necessary to give it all here, or to repeat the expressions of amazement and other comments, or the questions and answers which, from time to time, interrupted the narrative.

Briefly, the marvellous tale declared that the three sailors had lived for six years amongst an unknown race of people who inhabited a country hidden away in the very heart of the Sea of Sargasso. That they had at first been treated as slaves there, but that this particular sailor had latterly been made a servant of the reigning King, and accorded a certain amount of liberty. Then a revolt had broken out amongst the King's subjects, and the monarch had been obliged to fly and hide himself with a remnant of his followers in a remote district. From there, for a period, a sort of desultory, guerrilla warfare had been carried on with varying fortunes. At last, however, the King's party were surprised and once more reduced to hasty flight. The King himself embarked with his only child—an infant in arms—and a few followers, of whom Jackson was one, in a galley, but they were followed by two of their enemies' vessels, and a running fight ensued. The King and his companions were all killed by arrows; while Jackson was desperately wounded and became unconscious. The last he remembered was that a mist came up and separated the combatants, and he supposed that the pursuers had thus been prevented from capturing the galley. Then the rowers, finding that their leaders had all been killed, had probably taken the vessel to the nearest land and there deserted her, careless, or perhaps ignorant, of the fact that the bundle which was so tightly clasped in Jackson's arms was the still living infant son of their King.

Subsequently, the deserted vessel, with its helpless occupants, must have floated away and got caught in the current which had at last carried it to the place where Captain Woodham had met with it,

"And you, Master Lorry, or rather I should now say, Loronto—for Loronto is your true name," concluded the worthy captain, "you are the child I took from that drifting galley. It was your father I saw lying there with a great arrow through his heart. Sorry, very, very sorry I was, when I learned all this, that I had not been able to give him and his faithful followers decent burial. And I'm sorry, too, that, little thinking we should not have another chance, I did not bring away more than I did. I, however, took off his scarlet cloak to wrap you in, and brought away the diamond clasp by which it was fastened, the jewelled dagger at his side, the circlet I told you of, and a belt. These things I have carefully preserved; and to-day I shall hand them into your keeping."

Thus saying, Captain Woodham rose and went to a safe which stood in a corner of the room. Opening it, he unlocked an inner drawer and took out some parcels carefully wrapped in leather. Removing the covering of one of these, he displayed to view a slender crown of beautifully worked gold, in the front of which was a magnificent black opal, surrounded by diamonds and rubies worked into curious devices. Then he broke the seals of a quaint old belt and poured out from it a whole pile of treasure, consisting of small nuggets of pure gold, amongst an astonishing collection of diamonds and all kinds of precious stones. They lay there in a glittering heap beside the crown.

Both the young men had remained silent after the captain had concluded his story. Lorry, or, to give him his true name, Loronto, was lost in thought, and took little heed of the splendid jewels which were displayed before him. His thoughts went back to that drifting galley; to the tragedy that had taken place upon her bloodstained deck; to his father, lying there, cruelly done to death by his enemies. His friend Ralph understood his feelings and watched him in friendly sympathy.

Then the young man's breast heaved, his eyes lighted up with a stern fire, his mouth hardened. He drew himself up, and, turning to the Captain said, in a voice trembling with emotion:

"You spoke of some adventure—of some decision to be come to—do you mean that there is a way by which this foul deed—the murder of my father—can be avenged? Is such a thing possible? If so, you need not ask me to take time to consider; I am ready at once to embark in any undertaking, to run any risk, incur any danger, to punish those guilty of that cruel crime, if they are still alive and I can get at them! Though," he added regretfully, "it is likely enough that by this time the murderers may be dead, and so have escaped the punishment they deserved!"

"As to whether those who slew your father and usurped his place are still alive," returned the Captain, "I cannot say—but of that more later. The poor fellow, Jackson, left me certain explicit details and instructions, and if they are to be relied upon, the time is near for the opening of the channels through the weed—which takes place, he declared, at periodical intervals—when, if you choose, you will be able to find a way back to the land of your birth; of which, as I understand it, you are the rightful ruler."

"Will you stand by me—will you go with me?" asked Loronto with flashing eyes.

"Right willingly, my lad! It is what I have been saving myself for all these years!"

"And you, Ralph?"

"Can you ask?" cried Ralph. "Rather let me say, will you let me join with you?"

"Then we will set out together! And, if the fates should favour me, I swear that you two shall be the first and greatest sharers in whatever good fortune may come my way."

"And here," said Captain Woodham, handing him the circlet, "here is the sign of your authority—the crown your father wore. This wonderful black opal—the largest and most beautiful, as I truly believe, in the whole world—has been worn by your ancestors, I was told, through countless ages, and very glad am I that I should have been the means of saving it for you. May we both live to see you wear it in your rightful position in the country your father and forefathers ruled."

And the wonderful, lustrous opal seemed to flash with sudden, mysterious fire, as the young fellow held it in his hands for the first time in his life.

"I will not put it on my head," he declared solemnly, "while my father lies unavenged."

Then his glance travelled over the glistening heap of treasure, and he turned to Captain Woodham in amaze.

"And you—you, my dear friend—my second father—have guarded all these treasures for me!" said he with emotion. "You have kept them all these years, bringing me up and educating me out of your own scanty savings! Is it not so? You, who could have lived like a prince upon all this wealth, and none would have been the wiser!"

"I have done what I conceived to be my duty," answered Woodham simply. "I promised Jackson I would preserve everything intact until you should be twenty years old, according to the data he furnished as to the time of your birth; and then give it into your hands to do as you pleased with. It was a sacred trust, handed on from your father, through him, to me. I so regarded it—I gave my word—and I have kept it!"

"You have indeed!" exclaimed Loronto, "and how to show my gratitude—let alone repay you—I do not know! I shall never be able——"

"Pooh!" said the Captain, with a smile. "I want to see you restored to your own, my lad. For that purpose money will be wanted at the outset to fit out an expedition with. This, your father's treasure, would, I saw, provide; and I have been looking forward to the day when you would be old enough to make use of it.

"There is one thing more. You were wondering just now whether those who slew your father and usurped his place are still alive, and I answered that I could not say. I can, however, tell you this much—that they were still alive up to a couple of years ago. At that time they were still oppressing the country with a cruel, tyrannical rule and your father's faithful friends and followers—or those left of them—were still keeping up some sort of a guerrilla warfare."

Both his hearers started.

"How can you tell that?" asked Loronto in astonishment.

"It came to me in a very curious fashion. A small party of four castaways actually penetrated into the country, drifting in through a waterway which had been temporarily forced open by a great tidal wave. Now, by a most remarkable coincidence, one of the four was Peter Roff, who was with me when I discovered the derelict galley.

"Peter," continued the Captain, "is a rather quaint character. He is a capital sailor; a splendid shot, and a good hand with the cutlass; and as faithful and honest a man as can be found; but he has his weak point. He is very superstitious, and believes in witches and witchcraft, sorcery, and such-like foolishness. Therefore, when he came to me and solemnly gave me the account of his adventures, I was at first almost inclined to think that the worthy fellow's superstitious fancy had imagined it. When, however, he told me how they had been befriended by one of the outlaw chiefs, who had asked him whether he had ever heard tell of a derelict galley being found, with certain contents—amongst them a crown with a wonderfully fine black opal—then indeed I knew that Peter must have actually seen and spoken with one of those leaders who had espoused your father's cause."

"It's all very wonderful. It takes one's breath away!" exclaimed Loronto.

"Mine has gone long ago! I've lost the faculty of feeling surprised!" said Ralph philosophically.

"Well, you will be able to question the worthy Peter for yourselves shortly, for my friend, Professor Henson, in whose service he is, is returning to England in a week or two. He has taken Peter with him many times on his travels, and they have been half over the globe together. And that, by the way, reminds me that if—we should actually set out on this expedition, I have little doubt Professor Henson would like to accompany us if I were to give him the opportunity; in which case he would probably bring Peter with him.

"But," concluded Woodham, in a very serious tone, "I would not have you risk this wealth in what after all may prove to be an impossible venture—for we may fail to find a channel through the weed—without due consideration. That is why I have told you what I have to-day. To-morrow you will be twenty years old. Think over what I have said, ponder it to-night, and give me your final decision in the morning."

"I require no time for consideration," returned Loronto with enthusiasm. "My mind is made up! I shall follow the path which Fate has evidently marked out for me, let it end how it will!"

"Opening in the weed, sir!" called the lookout.

"Where away, Ben, where away?"

"Off the port bow, sir."

"What sort of an opening, Ben? Does it look like a creek? Does it run any distance? Look well, and see how far it runs up!"

"Aye, aye, sir." For half a minute there was silence. Then came the man's voice again:

"I can see a long channel, sir, a running up fur miles!"

With a curt, significant "Ha!" Captain Woodham went forward and mounted to where the look-out was stationed. He peered through his glass, and then returned aft to his two young friends, Loronto and Ralph, who were eagerly awaiting his report.

"All right, lads!" he cried, cheerily, even before he got to them. "Ben's right! There's an open channel, sure enough—and so far as I can judge, it looks like the one we want. It certainly runs in a long way!"

"At last, Lorry!" exclaimed Ralph to his chum. "I must confess I had been growing—a—well——"

"A little sceptical, Ralph; out with it," returned Loronto. "Your logico-mathematical training, if I may use such an expression, has led you, I fear, to look upon things romantic with a sort of doubting eye."

This remark was in allusion to Ralph's choice of a profession. He had been educated as an engineer, and had acquired—or perhaps sometimes affected—an ultra-practical, prosaic way of looking at things which was in contrast to the thoughtful, dreamy fits in which his chum sometimes indulged.

"Oh, well, one may be pardoned a little despondency under the circumstances," laughed Ralph. "Nearly a month have we spent prowling up and down on the outside of this dreary tract with nothing to look at day after day, but weed, weed—everlasting weed; and nothing to encourage one to hope that we should ever find what we came to look for. I fear, even now, that may be but a little creek we have chanced upon."

"A creek, say you? Look yonder!" cried Captain Woodham. "There lies the channel I rowed up in my boat that night—yonder is the place where I boarded the galley! So far as I can judge, this is truly the same channel, opened again—as that poor fellow Jackson said it would!"

Full of curiosity, the three crowded to the side of the vessel and gazed for a while in silence at the scene.

It was all as the Captain had described it to them. On one side there was the open sea; on the other, stretching far as the eye could reach, the interminable waste of weed—and now, almost straight ahead of them, a broad, open waterway, running right up into its midst.

"We must call the Professor to see this," said Captain Woodham. "He also has been among the unbelievers, I fancy. D'ye know where he is, Ralph?"

"I expect he's in his cabin setting up some specimens of a very curious creature which he captured when out in the boat yesterday amongst the weed, and which I understand is quite new to science."

Professor Henson, the friend of whom Captain Woodham had spoken, had gladly accepted his invitation to join the expedition in the hope of making some fresh discoveries. Though a comparatively young man he was already well known as an able scientist.

A seaman sent below to fetch the Professor returned with that gentleman's assistant and general factotum, Peter Roff. Peter, as we now, had formerly been a sailor, but of late years had travelled, a good deal with the man of science.

Peter was a character in his way; and since his intimate association with the Professor was apt to give himself airs, pluming himself upon the possession of scraps of learning picked up from his master, backed by a smattering of scientific terms—which he often ludicrously distorted.

"Well, Peter," cried Ralph, as he caught sight of the man's sturdy figure and good-humoured face, "I suppose the Professor's too busy to bother about the discovery we have made? What did you catch yesterday that has proved so interesting?"

Peter shook his head rather contemptuously.

"The Perfessor thinks a mighty lot o' the critter," was his answer, "but I can't say as I do! It's a square-shaped beast, cert'nly; a sort of 'alf butterfly, 'alf bird—but I don't think much of un—'cos why?—'ee doan't belong t' any proper spices, the Perfessor says 'ee's got no genius t' speak of—and as to 'is family—well, it can't be up to much, 'cos the Perfessor don't know it—never heerd on it!"

The Captain winked, the two young fellows laughed, and Peter, after a good look at the open channel, went back to report to his master.

"Well, there's plenty of time for the Professor to come and have a look," presently observed Woodham. "There will be a good moon tonight, and I think perhaps it might be better to wait for it; then alter our rig and creep up the channel quietly. If we should meet with any unfriendly natives it may scare 'em off and make it easier to get the yacht through the narrow parts into the open water which we know must lie somewhere beyond."

The words "alter our rig" require explanation. The yacht the adventurers were on—named the Wyvern—had been specially fitted out and adapted for this expedition, and had been supplied with some rather remarkable contrivances in addition to every ordinary modern improvement. She was well armed, and carried a crew who had been carefully selected and drilled by Captain Woodham himself. She had electric searchlights, and was propelled by engines worked not by steam, but by petrol.

Beyond all this, however, she boasted an altogether novel contrivance by which she could be converted, at short notice, into the outward semblance of a most awful monster—carrying out, as nearly as an exuberant fancy could suggest, the traditional idea of the mythical creature she had been named after. When thus changed she appeared as a very "fearsome wild-fowl!" indeed. A rearing, scaly neck, flanked by two wings, rose at the bow, carrying a hideous head with gaping jaws which opened and shut in a most natural manner, and two great eyes through which shot the dazzling, basilisk-like glare of the powerful searchlights. The two movable masts and telescopic funnel gave place to a sort of "turtle back," which covered the whole vessel from stem to stern, and ended in a long "practicable" tail, which could be made to lash the Waters into foam.

The idea of this grotesque disguise had been Ralph's, and he prided himself not a little on the life-like manner in which he had carried it out. While in home waters, or lying in harbour, the yacht showed a funnel and two masts, and appeared as trim and handsome a vessel as any seaman could desire. But when transformed, as described, she appeared—especially at night, or in uncertain light—well calculated to fulfil Ralph's idea of "astonishing the natives" of the unknown country they were in search of.

For the present, however, she was still in appearance merely a large private yacht; and they waited for darkness before making the necessary alteration.

When night fell she was rapidly transformed, and as the moon rose she entered the channel, and proceeded to cautiously feel her way into the midst of that vast ocean of weed. The channel grew wider as she advanced, opening out here and there, into lakes or lagoons, connected by numerous cross channels, until the adventurers found themselves involved in a sort of water maze.

Steering by compass, her Captain kept the vessel upon as straight a course as circumstances permitted, and by degrees those on board of her lost sight of the open sea and began to look anxiously ahead.

It had been easy enough, once they sighted the channel, to penetrate into this strange region; it might be a different affair altogether to find their way out again should the necessity arise!

Meantime all was silent—oppressively silent—and desolate—a very wilderness of desolation, it seemed. And ever, as they sailed onwards, they passed numbers of old hulks, which became continually more and more ancient in shape and rig. Gaunt and grim they showed above the general level of the weed, like ghosts of a long dead past—inexpressibly sad in their loneliness; strangely weird, mysterious monuments of bygone ages. The queer appearance the disguised vessel made as she crept up the waterways, uncouth as it was, scarcely seemed out of place amid such surroundings.

Presently, however, open water was seen ahead, and beyond, a reflection in the sky, as from a great fire or other unusual illumination.

In the interest and speculation aroused by these signs, the adventurers gradually threw off the depression which had begun to seize upon their spirits, and when, a little later, the strange-looking craft glided out of the intricate network of waterways into the broad expanse of what appeared to be a great, salt-water lake, Ralph drew a long breath. "Ah! Now we can breathe again!" he cried. "It was like being cooped up in a graveyard!"

The yacht was headed straight across the open water, and gradually the distant land rose before the gaze of the travellers until it loomed up in the shape of a high mountain, whose gloomy-looking, precipitous sides soon hid the moon, and threw a deep shadow over everything below.

Into this shadow the yacht crept, and the travellers eagerly scanned the shore, which appeared quite deserted. There was no sign of any habitation. In character it was wild and rocky, thickly covered in some places with dense thickets of dark-looking trees like firs; in others it was open, with low bushes scattered about.

Yet from over the mountain's top there still rose into the deep blue vault of the sky above, that strange appearance as of a reflection of some lurid light.

Captain Woodham looked up and down the coast and shook his head.

"I don't like the look of it," he said, scrutinising his surroundings with the eye of an experienced seaman. "Just the place for sunken rocks! I'd rather not cruise along this shore in the dark—and it won't do to anchor. If one had to shift suddenly it would mean the loss of one's anchor—and cable to boot!"

"I'm going ashore to investigate," Loronto declared. "This, as I understand it, is my native land, and I am full of curiosity to find out something of what it is like."

"It's a queer sort of home-coming for you, Lorry," said Ralph musingly. "I am coming with you, of course."

"And so am I!" exclaimed Professor Henson. He had "come out of his museum," as Ralph expressed it, some little time before, and had been a silent observer thus far of all the incidents of their venture into the midst of the weed.

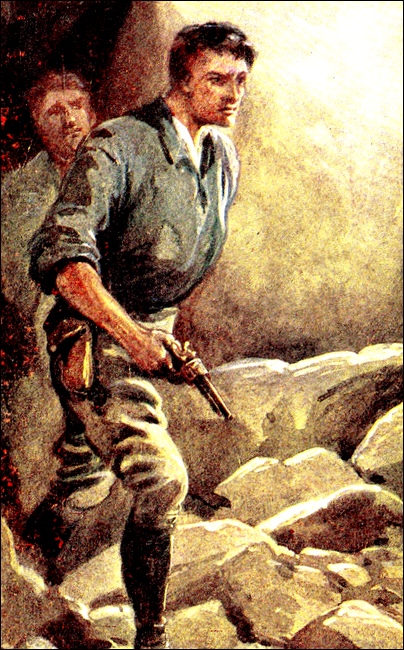

The two chums loaded their rifles and revolvers and buckled on a cutlass each—for under the Captain's tuition they had both become expert swordsmen—and the Professor gravely imitated these precautions. Beside the towering forms of the young athletes the scientist looked small—for he was not by any means a big man—but he was tough and wiry, and known to be not only a good fighter, but plucky withal. With him went the worthy Peter.

Half a dozen trusty seamen, all well armed, rowed them ashore, and four of these were left in the boat, the other two being placed at a little distance as scouts.

Then the three, with only Peter as their attendant, made straight for the mountain, and began to ascend its rocky heights.

Slowly, and in silence, the little party climbed the mountain side. As a rule, Peter was somewhat garrulous; but under the influence of the potent spell cast upon them all by the strangeness of their surroundings, and the uncertainty as to what their adventure might lead to, even the talkative sailor recognised the wisdom of making no sound which might betray their presence to possible enemies.

Thus they pressed on until they were within a few yards of the summit. There they paused and listened.

A curious, low hum could be distinguished, coming, seemingly, over the top of the mountain. Now that they were higher, too, they could perceive that the glow in the sky was brighter.

A whispered consultation took place. Both the young men felt the thrill which precedes, the plunge, as it were, into a new discovery—for that they were on the verge of a discovery they felt certain. The very air up there seemed charged with a vague sense of something beyond. Ralph threw aside his "practical" theories, and his heightened colour and sparkling eyes showed that he was on the tip-toe of expectation. The Professor, though his wanderings over the earth had made him less easily impressed, evinced, by his restless manner, that he was looking for a surprise—a new experience.

And certainly none of them were disappointed; for, a minute or two later, they had topped the hill, and were looking down upon the other side—gazing down upon a scene so utterly strange and unexpected that they scarcely knew whether to regard it as reality or as the illusive effect of some wondrous hallucination.

They saw below them, upon the further side of an intervening stretch of water, another shore, and upon it a populous city, which, from where they were, appeared to be of marvellous beauty. There were stately palaces and buildings, noble-looking embankments, promenades, and bridges. There were towers and spires glistening in the moonlight with a sheen as of silver and gold. Beautiful gardens and grassy slopes stretched down to the water's edge amongst fountains, terraces, or colonnades. Beyond, were lofty viaducts, with a background of towering mountains. The whole of this fairy-like scene was ablaze with lights, while, in places, upon sculptured columns, were censers, from which dancing flames leaped upwards, and spiral columns of light vapour ascended towards the sky.

The gardens and terraces were filled with gaily-dressed crowds, and upon the water boats passed to and fro, some, with white, glistening sails, drifting slowly in the light breeze—others, of gondola shape, propelled lazily but gracefully by wielders of long paddles.

There was a general air as of a city "en fête"; and now and again, above the general confused hum, arose the sounds, softened and rendered indistinct by distance, of laughter and music.

Loronto and Ralph gazed upon this scene with indescribable feelings. For the first time there arose in the breast of the former a perception of the position he had been born to and had lost. Could it be possible, he asked himself, that he was really, as he had been assured, the rightful ruler of this golden city? It seemed a thing hardly to be believed; surely it must be a dream—or there had been a mistake somewhere!

In Ralph's mind, all his pseudo-practical ideas fell away, toppled over, so to speak, and in their place came a rush of romantic enthusiasm bubbling over with wonder and delight.

"By Jove, Lorry!" he gasped, under his breath, "you're a lucky fellow! Fancy! Heir to such a little paradise of a kingdom——"

Just then Peter laid a hand upon the speaker's arm with a warning pressure.

Not far away, a little below where they were standing, a rocky bluff ran out from the side of the hill, forming a spur or isolated pinnacle, which commanded an extensive view over the open water the travellers had come across, and the region of weed beyond.

There had been a sort of clicking sound, and a clang, as of the opening and closing of an iron gate! This sound, which had caught Peter's sharp ears, had come from the direction of a dense thicket of trees near the bluff; and he silently pulled his companions down into the shelter of some bushes from which they could watch without being seen.

He had scarcely done so, when a figure was seen emerging from the thicket, and it immediately afterwards appeared walking along the ridge or narrow ledge which connected the bluff with the side of the hill.

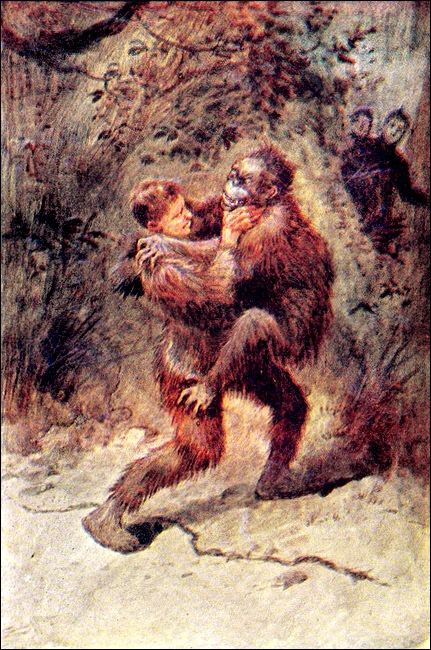

Arrived at the extreme edge of the bluff, lighted by the moonlight which fell across the summit of the hill, the figure remained gazing, as if in deep thought, out over the landscape. It was the figure of an old man with long white hair and beard, and noble-looking in pose, clad in a flowing dark robe, with a girdle round the waist. The breeze blew his long, white locks from his face, revealing a countenance which, in the bright moonlight, appeared handsome and attractive, yet tinged with a certain stern sadness. In his mien, as he gazed fixedly across the landscape, was an air as of expectation, and he raised his arms and extended them before him, as if in sympathy with some mentally-uttered exhortation.

Suddenly, Peter pointed to some bushes below the bluff, and the others, looking carefully, could see dark forms creeping stealthily in the shadow towards the solitary figure. They carried drawn swords in their hands, and all, it could be seen, by a slight gleam here and there, deep though the shadow was, wore some sort of armour.

The unseen spectators knew nothing of any of these people, but their sympathies went out at once to the figure on the bluff. There was something both of dignity and of pathos about him which appealed to them, and apart from that, the sight of several armed men, stealthily attacking another, who was unarmed and unsuspecting, naturally appeared to them brutal and cowardly.

They, therefore, as with one accord, decided to intervene and prevent what otherwise seemed likely to be a cold-blooded murder. At the same time they knew that it would be wiser to avoid the use of firearms if possible—for it had now become clear that the place was by no means uninhabited or deserted, as they had thought. The noise of firearms might precipitate matters, and cause complications which it would be better, for a while, at any rate, to avoid.

With these thoughts in his mind, Loronto drew his cutlass, and, signing to his companions to follow him, he commenced against the attackers a flank movement as silent and stealthy as their own.

Of the assailants there were half a dozen, and they now divided into two parties, four on one side of the narrow ridge and two on the other. The two detailed for the further side disappeared from view, while the others were so intent upon their design that they saw nothing of the little group closing in behind them.

A minute later, the leader had climbed up far enough, and his head and shoulders showed for a moment in the moonlight as he rose to deal a cowardly blow at his intended victim. But as he raised his arm, it was seized from behind in a grip which all but pulled it from the socket. The sword was wrenched from his grasp and thrown clattering down the rocks. Then two arms closed round his body, he was lifted off his feet, and cast down after his sword.

Loronto, who had thus disposed of the leader, leaped into his place, then up on the bluff, cutlass in hand, just in time to ward off a blow from a man who had appeared above the edge upon the other side. At the same moment, the old man these people had come to attack perceived his danger, and, with a muttered word, drew back along the ridge.

Below, Ralph and his two companions were engaged in a struggle with the three assailants still remaining on that side. This left Loronto with two to deal with on the bluff itself.

He had seized one as he sprang up, but had been himself grasped by the other, and the three were now locked in a deadly conflict which threatened to end in their all rolling down the precipice together.

The table or platform of rock upon which they fought lay full in the moonbeams which glinted across the top of the hill. They gleamed upon the polished armour of the two assailants, and at times there was a flash of a blade. All around was deep shadow, and to those below who were watching the struggle with breathless interest the conflict seemed weird and almost unreal. The men in the waiting boat, Captain Woodham and others of the crew upon the deck of the yacht, all looked upwards at the three figures as they swayed to and fro and swung about here and there, sometimes seeming to be poised upon the very edge of the precipice, then working back into the middle of the bluff.

The Captain held a rifle in his hand and twice he put it to his shoulder; but the figures were so interlocked that no chance offered to get in a shot with safety.

Suddenly the three figures parted. One of them fell flat upon the rock; another staggered backwards and with a loud cry disappeared into the shadows, and in the momentary stillness which followed there could be heard the sickening sound of a heavy body falling from rock to rock and crashing through the tops of the trees below.

One stood out on the bluff alone; and in a moment or two it became clear that it was Loronto. With a great effort he had summoned up all his strength and thrown the two from him—one with such force that he lay motionless upon the flat rock beside the victor—while the other had crashed over the side.

A cheer went up from the watchers below, and just then Ralph also showed upon the bluff. He had disposed of his own opponent and had climbed up to the assistance of his chum.

Meantime the two seamen left as scouts had ascended to the foot of the bluff and aided the Professor and Peter to settle with the other two.

For a minute there seemed to be an end of the encounter; when suddenly there came an outcry, and a number of fresh figures could be dimly seen making for the bluff from three sides.

Four or five climbed up on to it with such agility that the two victors found themselves, ere they had had time to recover their breath, involved in a fresh struggle, and this time against much greater odds.

Captain Woodham shouted an order to the men waiting in the boat ashore to leave her and hasten to the aid of their friends, and himself jumped into another boat which he had previously ordered to be got ready in case it might be wanted. A party of men fully armed had already taken their places in her, and as the Captain sprang in they started rowing.

But long before they reached the shore something had taken place above which rendered their aid unnecessary.

When Loronto had first appeared on the bluff and warded off a blow which had been aimed at the old man who had been standing there alone, the latter had, as already stated, retreated along the ridge. For a moment or two he had stood watching the struggle which followed as though too surprised to do anything. Then he looked about keenly first in one direction, then in another, and finally disappeared into the thicket of trees from which he had emerged a little while before.

Now, just as the fresh assailants showed themselves, this man appeared again, but this time not alone. With him there came a rush of armed men who threw themselves with resistless fury into the work of assisting the two young strangers.

Under a leader who seemed a veritable giant in stature—a man clad in a complete suit of magnificent armour—they speedily turned the tables upon the crowd of assailants, followed them up with relentless persistence, and in a few minutes had accounted for every one, bringing back with them, as bound prisoners, those who had attempted to save themselves by flight.

When the fight was over their leader and his companions, the old man first seen, turned to the strangers and spoke in a language which they could not understand. Then, seeing that it was strange to them, the one in armour spoke again, this time, not a little to their surprise, in good English, asking who they were and whence they came.

Loronto and Ralph looked at each other, then at their friend the Professor, who by that time had gained the bluff and was standing beside them. Their surprise at hearing themselves addressed in their own language was so great that for a moment or two they gave no answer.

Just then Captain Woodham, at the head of a squad of sailors, appeared on the hillside a little below them, and not understanding the situation, called out to his friends to ask them how it fared with them.

The stranger in the suit of armour turned to him.

"If you are one of the leaders here I would speak with you," said he. "I perceive you are a large party, and I desire a word or two with the leaders."

But ere anyone could reply the old man in the dark robe uttered a strange cry. He had been staring hard at Loronto and now he pressed forward and peered into the young fellow's face.

"Who are you, my lord?" he asked, in English, in quick eager tones. "Whence come you, and why?" He turned Loronto about so that the moonlight fell upon his face, and gazed at him with a strained anxiety which was almost painful to see. Then he cried out again, and, turning round, ran off the bluff and disappeared once more into the thicket.

The man in armour had watched all this in silence. Now he repeated his request.

"I would speak with your leaders," he said again.

"Sir," said Woodham, "I suppose we may assume that your intentions towards us are friendly since you have, as I have seen, extended timely assistance to my companions? At the same time, we do not know how we are situated here, or what risks we may be running by remaining where we are. I'm a blunt man, a plain, straightforward seaman, and I feel more at home on the deck of my ship than on shore in a strange country. So I say, if you want to talk, come aboard my ship. You'll be quite safe——"

"Ha! You have a ship! Where?"

"Here; just off the shore below us."

"But—how did you bring her here?"

"Well, we just came along an open channel we saw in the weed."

"But you must have had an object; no man trusts his ship inside the weed unless he either knows there is open wafer beyond or has some very urgent motive prompting him to run a great risk. Tell me, come ye in peace, or with warlike intentions?"

"That is as may be," returned the Captain cautiously. "If we had been asked that question an hour ago, I should have answered, 'we come in peace'; but after what has occurred I beg to observe that we are quite capable of taking our own part if a quarrel be forced upon us."

"This helps us little," returned the other, with a gesture of impatience. "Tell me why ye came at all—then can I better judge whether to offer my friendship. If I find on examination that I cannot grant it, then it were better ye should return at once by the way by which ye came whilst that way is open; for in coming hither you are courting dangers you little dream of, and which, well-armed though you may be, will overwhelm you if you have to trust to your own prowess alone!"

At this the adventurers looked at one another inquiringly. Captain Woodham and the Professor smiled. They considered their party, armed as they were with firearms, a match for any possible number of old-world warriors armed only with swords, spears, and bows and arrows.

But the two younger men were impressed with the dignity and earnestness of the stranger's manner, and they instinctively felt that there was something deeper in his warning than appeared on the surface.

They had been observing him attentively, and the more they saw of him the more his personality impressed them.

They saw before them a man of great height, with a powerfully-built frame, clad in a complete suit of armour made partly of steel and partly of gold and silver. Beneath a coat of mail was a red satin tunic embroidered with a star, the centre being black, and the rays, as it were, in gold. A cloak of dark hue, with white lining hung from his shoulders, where it was fastened with a diamond clasp. Round his left arm was a band as of some order or decoration, the centre being a black opal set in a ring of diamonds. Upon his head was a helmet of steel, damascened in gold and silver; by his side hung a sword of immense size, and round his waist, in a jewelled belt, was a dagger with hilt also set with precious stones.

But remarkable and surprising as was the dress, the face, figure, and general air of the stranger were still more striking. The hair and beard were iron grey, but he showed no other signs of age.

Upright in carriage, muscular and supple in build, he exhibited in his movements the ease and grace which often accompany great strength, while his face had in it that rare combination of sternness and kindliness which denotes the man born to command. This was particularly noticeable in the eyes, which could change in a moment from the flash of anger, or contempt, to the tenderest sympathy and pity.

Towards this man Loronto felt strangely drawn. There was something in his glance which attracted and held him, and there was that in his general bearing and manner which commanded his admiration.

And as he looked upon him he noticed again the diamond clasp which fastened his cloak at the shoulder. It was exactly like his own, the one which Captain Woodham had taken from that drifting galley; the one which they believed had belonged to Loronto's father.

When they entered the region of the weed, some fancy had led Loronto to take this clasp from the safe in the cabin, in which it lay with the wonderful black opal, and place it in his pocket. An idea now came upon him like an inspiration. He drew it out and held it in the rays of the moon so that the other could see it.

"Perhaps, sir," he said, in an undertone, so that his words should not be heard by everyone, "perhaps this clasp, which I perceive resembles one you are wearing, may convey something to your mind."

The stranger turned to him in surprise at the words, and then, as his glance fell upon the clasp, it was evident that he was deeply moved. He started forward and seized it, gazing with amazement from the jewel to the face of its owner.

As the other had done, he turned Loronto's face towards the moonlight, and gazed into it fixedly.

"Your name, lad, your name?" he asked, quickly.

"I'm called Loronto," was the quiet answer.

At the same moment the man in the dark robe came running out of the wood, bringing with him three or four others. He heard the words.

"Loronto!" he cried. "I knew it! I felt sure of it the moment my old eyes fell upon his face! He has come to us, as I knew he would! He has come—the son of my dear dead master—the son for whom I have watched, and waited, and watched again during so many years! Friends, greet him, for he is your lawful ruler! There, before you, stands your lord, Prince Loronto!"

And overcome by his emotion, the faithful watcher sank upon the rock in a faint.

An hour later, Loronto and his friends were once more looking down upon the wondrous city which they had caught a glimpse of from the top of the hill they had ascended.

Now they were gazing upon it, not from that point, but from a hidden post of observation within the hill itself—a place to which they had been conducted through a secret underground passage-way by their new friends.

In the interval many things had been explained to them, but in a manner so hasty and fragmentary as chiefly to lead them to desire further enlightenment which could not then be given.

They had, however, learned the names of some of their hosts. Thus, the one Loronto had saved from his cowardly assailants was named Ralmedus. Formerly he had been a priest, but had seceded from the fraternity. Another—the one dressed in the suit of armour—was named Montamah. He was not a native of the land, it seemed, but had drifted there, many years before, in a derelict vessel. There he had, by some turn of Fate's wheel, or, more probably, through his own inherent gifts, risen to great power and influence in the land, and had been the trusted adviser and counsellor of Dominta, Loronto's father. Who he was exactly, or whence he came, was involved in some mystery. It was a matter to which he himself—as the new-comers afterwards found—never referred, and he was not one whom any man would care to question upon subjects he desired to keep to himself.

Other two there were whom the adventurers were not a little surprised to meet—the two men, namely, who had been shipwrecked with Jackson, and had drifted to the land with him and shared his captivity. Their names were Galston and Ridge—British sailors both, though the first-named seemed to have been a man of some education. Since Jackson's disappearance, Fate had played many strange pranks with these two human derelicts, of which more will be told later on. It was owing partly to them, and partly to Montamah, that Ralmedus and a few others had learned to speak English.

Loronto watched with dreamy eyes the city over which his father and his ancestors had ruled through many ages. He only now for the first time learned its name—Ireenia—for upon that, as well as many other points, the information given by the unfortunate Jackson before his death had been incomplete.

Ralph came to the side of his friend, and Loronto, looking up with a start, asked him where he had been. He laughed as he replied:

"While you've been dreaming I've been working, talking, asking questions. What has occurred to-night shows that these caverns, which have long been the secret meeting-place of our new friends, will be no longer safe for them; therefore they are anxious to remove some stores which they had accumulated here. These are now being carried on board the yacht. There are suits of armour, swords, spears, and so on; bundles of fireworks——"

"Fireworks!" exclaimed Loronto. "How can that be?"

"Oh, there are lots of things, I am told, we have yet to hear of, far more surprising than that. It is a land of many wonders—so they declare. As to fireworks—well, have we not been told that they were known to the Chinese two thousand years ago? So why should it not be the same with this ancient people?"

"That is reasonable, certainly. Anything else?"

"Why, yes, here's a rum thing. That old johnny we went forth to save——"

"You mean Ralmedus—don't laugh at him——"

"Nay, my dear Lorry, I am full of admiration and wonder at the old joker's-er—I mean the grand old man's—patience and pertinacity. The fact that certain channels to the sea are open at intervals is naturally well known to the folk here—and every time they have been open the dear old jo—I mean Ralmedus—has kept a watch, believing that the lost Jackson would return bringing you with him."

"How do you mean? How could they guess——"

"That's just the wonder of it. The old galley Captain Woodham saw was afterwards found, it would seem, by them very much as the Captain left it; but Jackson had gone—so had you—so had your father's cloak with the diamond clasp; and last, but not least, the crown of the Black Opal, as they call it, had disappeared also. Thus they guessed that strangers had found the galley and carried off all that was missing. The question was, would Jackson—or, at least, would you—ever return? The old—I mean Ralmedus, prophesied—and he prophesied that you would return. To show his belief in his own predictions, he has watched and watched through the years—and now that his prophecy has been fulfilled the dear old chap is beside himself with joy—as they all are, in fact. In particular, they are crowing over the fact that you have brought back the much prized Crown of the Black Opal, for it will give them and you, it seems, a great advantage over your enemies. Their leader is one named Demundah. He is the present ruler of the country—uncrowned, however, because the crown was missing, and by their ancient laws no other crown—not even a good paste imitation—may be used in its stead. The old chappie—I mean Ralmedus—and his little band of stalwarts have come here to secret meetings, whenever the channels were open, expressly in the hope of being the first to meet you and so prevent your unwittingly falling into the clutches of your enemies. Strange to say, this particular night, of all nights—after their remaining unsuspected for so many years—some of Demundah's guards got to have an inkling of the matter and lay in wait for them."

"That is strange, indeed! But what wonderful devotion to my father's memory on the part of Ralmedus and his friends does this show! How, then, came Ralmedus, however, to miss seeing the yacht as we came across the open water in the bright moonlight?"

"Why," returned Ralph, with an air, half-puzzled, half-humorous, "I think that the old Johnny—he is a regular old brick—but I think that he must be a bit daft—off his head, you know. He saw us coming right enough; but thought we were—what do you think?"

"Goodness knows!" answered Loronto wonderingly. "No doubt our outlandish disguise puzzled him——"

"Not at all; he says he merely thought we were a—a—something or other—he mentioned some name, but I have forgotten it. It amounts, however, to this, that he took us for a real monster, and so—thought nothing of it!" And Ralph burst out laughing. "Mustn't he be a bit daft?"

Loronto looked at his chum in astonishment. "Took us for a real live monster?" he exclaimed. "What on earth does that mean?"

"I suppose he meant to imply that there are, in this queer country, real monsters as big and as awful-looking as my theatrical get-up—and that they are sufficiently common to cause no particular surprise if one is seen taking a promenade in the sweet moonlight alone."

"It sounds most extraordinary!" Loronto cried, in growing wonder; but ere he could pursue the matter further, Montamah entered the chamber where the two were talking.

"See!" said he, pointing through the well-screened window in the rock, "yonder are the grand illuminations in honour of your rival—the usurper, Demundah. To-night's fête is in his honour. Now the firework display is about to begin. You can watch it for a few minutes, and then we ought to start. Everything is on board your vessel in readiness."

As he spoke, there came across the water the sound of crackling reports and detonations, coloured fires burst out here and there, and rockets ascended into the air.

"They understand how to make good rockets, at any rate," observed Ralph, admiringly. "Those to the left are as fine as any I ever saw. They seem to be pleasing the crowd, too, judging by the cries of delight——"

"They are not cries of that sort," exclaimed Montamah, hurriedly, anxiety evident in his tone. "Ha! I feared so! Do you see those blue fireballs going up? That means danger for us! One of those who first attacked you to-night probably got away and has given the alarm. Quick! Follow me! We must hasten!"

When they reached their vessel they found that she had cast her skin, so to speak. She was once more the trim private yacht. This alteration had been made by the advice of Montamah.

They embarked upon her without further incident, and she put off from the shore, steering in a direction pointed out by Montamah, who now practically took command, as by general consent. She was headed across the open water, following a course to the east of the channels through which they had come.

They carried with them a dozen of Montamah's followers—rough, sturdy warriors in a dress partly of leather or buskin and partly of plate armour. Their only arms were swords or spears.

Besides these, there were some half-dozen prisoners captured from the party who had attacked them on shore. They had been searched and their arms taken from them, and they were loosely bound together.

"Captain," said Montamah, "I want you to lend me a rifle, and select a dozen of your best rifle shots to aid me, and to do as I shall direct."

"Let us make two out of the dozen—we can shoot," said Loronto, indicating his chum and himself. "The Professor can shoot, too—and, for the matter of that, so can the Captain——"

"I want him to make play with your cannon," was the reply. "Ah! See! They are beginning!"

From the high ground on the shore they had left, a stream of fire and sparks shot up into the air like a very big, heavy rocket. It reached out, as it were, towards them, and then the trail of light disappeared, leaving only a solitary, fiery red ball, which remained suspended in the air and travelled towards them like a sort of floating star. It seemed to travel slowly for a projectile, yet it moved faster than the yacht.

"You see that floating light," cried Montamah. "Aim at it; try to hit it, and any other that comes within range. If it touches your ship it will burn a hole clean through her; while if it touches the water near us it will surround us in a mist so dense that one can scarcely breathe. Round the headland yonder, perhaps, or elsewhere out of sight, hundreds of men in their war-galleys are waiting till this mist enshrouds us. Then they will issue forth and attack us, and we shall have but little chance against the numbers of desperate men they will hurl upon us."

As he spoke he fired at the red star, and evidently must have hit it, for it exploded with a sharp hissing report and disappeared. There was some hissing where pieces dropped into the water, and a few jets of steam shot up; and that was all. The "Long Tom" boomed out at the same moment, sending a shell at the place the rocket had sprung from.

Meantime, other rockets flew out from various points, and, despite more shells sent in reply, red stars floated through the air in several directions. Most of them were fired so as to get windward of the vessel, or to pass over their heads, and it was to these that the party of sharpshooters, under the direction of their leader, devoted their chief attention. Many of them were struck and dispersed harmlessly, but, in spite of all they could do, one or two here and there dropped directly in the vessel's path. No sooner did they come in contact with the water than masses of heavy, low-lying vapour arose, which hung in compact clouds, almost like something solid.

Yet there was no enemy anywhere to be seen. Their cannon, their Maxims, their rifles, their search-lights, were all useless.

Captain Woodham grew angry as he vainly tried to head the gathering banks of vapour, and to stop the rocket firers. Each time a rocket appeared, "Long Tom," sent a shell hurtling through the air towards the place from which it had started, till the gathering mist prevented his seeing them. But still the sound of them could be heard—now here, now there—though they could no longer be seen.

The yacht was stopped, and now lay motionless upon the water, in the centre of a great circle of vapour which had already shut out the view beyond, and was closing in upon all sides. Slowly it spread towards the vessel in heavy, rolling masses, suggestive of the writhing forms of phantom serpents hungering to enclose her in their fatal folds.

The moon was setting, and as it grew darker there was a strange, brooding silence, broken only by an occasional rifle shot when one of the floating red stars showed through the banks of fog and came within range.

Leaving the sharpshooters to deal with these, and thus keep a clear space round the yacht as long as possible, Montamah held a hurried consultation with Captain Woodham as to their next proceedings.

At his instance the Wyvern was once more metamorphosed, and took on again the likeness of a hideous, scaly monster.

By the time the change had been effected, the red fire-balls had ceased to appear, and the marksmen left on the watch could see nothing around them save the banks of thick fog.

"What is that noise?" Ralph asked of Montamah.

Upon the still air had risen a confused murmur, which seemed to swell in volume each minute.

"It is the sound of our enemies gathering round us in the mist," was the reply. "They are completing their circle, and hope to hem us in."

"Can't we make a dash upon some of them and give 'em a bit of a lesson?" Loronto put in impatiently. "It seems rather weak to wait here idle while they are quietly perfecting their little arrangements!"

"We shall do better by waiting till the moon has quite gone," the other answered quietly. "My plan is then to double back and break through their line behind us, which is pretty certain to be weaker than that in front of us. They saw a ship disappear in the mist in one direction. If now they see what, in the darkness, will seem to be a startling and unexpected apparition going in quite a different direction, they will be more likely to clear out of its way, and hasten off to make sure of the capture of the ship, which they will suppose to be still struggling in the mist. That this plan should have a fair trial it is necessary that there should be no more shooting on our side, and no sign of any living person on board."

"Good for you!" said Ralph approvingly. "It sounds a likely plan. The only thing I don't like about it is that it looks like hiding from the beggars. They'll think we're afraid of 'em."

"It will save our ammunition if it succeeds," said Montamah. "We shall be glad of it later on, and my advice is not to fire a single shot except you are compelled. The stores you have brought are not inexhaustible, and by and by they may be worth more than their weight in gold to us."

There could be no gainsaying the wisdom of this advice, and the young fellows said no more, but watched in silent curiosity the next proceedings of their new friend and his followers. From amongst the various packages they had brought on board, they now selected certain bundles from which, when they were opened, there rolled out on the deck a number of what seemed to be dominos, or masked head-dresses.

"Quick!" exclaimed Montamah to Captain Woodham. "Call up your men! Every man must don one of these!"

"What in thunder may they be?" demanded the astonished skipper.

"Masks; and unless you wear them the chances are you will never get through yonder fog alive!" was the enigmatical answer.

The professor would have paused to examine the curious appliances, but Montamah was insistent, and a few minutes later all were attired in the strange headgear. It consisted of a headpiece with a mask attached, which fitted closely over the face and fastened at the back with straps. The orifices which were left to breathe through were filled in with some highly aromatic fibrous material, which, Montamah explained, acted as a neutraliser of the noxious vapours they were about to pass through. For the most part these head pieces were of black, and plainly made, but some were fashioned with high ear-pieces and snouts roughly resembling the heads of animals, giving the wearers a grotesque and hideous appearance.

These preliminaries arranged, the "turtle back," which could be turned over so as to completely cover the whole deck from stem to stern, was drawn across, and the order was given to move slowly ahead.