RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"The Temple of Fire," Sir Isaac Pitmans & Sons, London, 1905

"The Temple of Fire," The Boys' Friend Library, London, 1917

This story was originally published in 1904 by The Amalgamated Press, London, under the title The Sunken Island; or, The Pirates of Atlantis in the Union Jack Library series (Vol. 2, No. 30). It was printed under the byline "Fenton Ash"—one of Francis Henry Atkin's noms de plume.

The version of the novel given here was prepared from the edition published, with a preface and some editorial changes, by Sir Isaac Pitmans & Sons, London, in the following year under the new title The Temple of Fire, or: The Mysterious Island. For this edition Atkins used another of his pseudonyms—"Fred Ashley."

RGL offers illustrated e-book versions of both editions of the novel under their original titles.

—Roy Glashan, 6 May 2018.

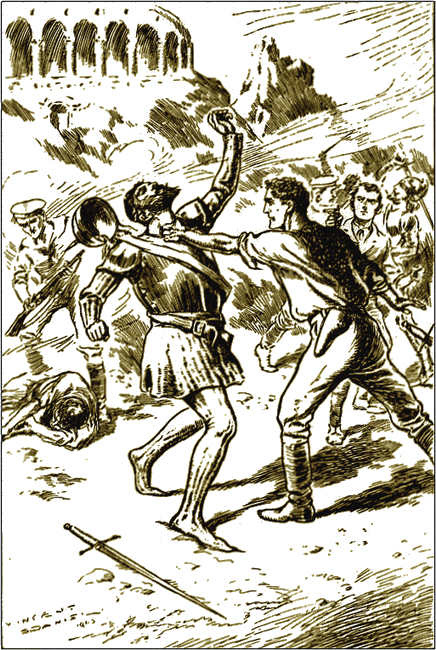

Frontispiece.

And then, all unexpected, came a rush of armed men.

THE up-to-date, quasi-scientific romance or adventure story is so well known in these days as a distinct type of juvenile fiction, that no remarks would be called for by way of introduction to the present effort, were it not that it happens to be the first of my tales of the kind to be issued in book form.

My previous "fanciful flights" in this field have been printed only in the boys' magazines for which they were written; but if one may judge by the favour with which they have been received by the youthful readers of those publications, then I should have the best of reasons for hoping that this new venture may prove popular and successful.

We all know, however, that boys do not choose their own books to the same extent that they choose their weekly magazines. Their books are, for the most part, probably, bought for them as gifts by their friends and relatives, who are sometimes a little shy of a "new writer." A few words to them, therefore, may not be out of place.

I would like to say, for their satisfaction, that they will not find in my imaginative creations anything which is unsuitable for healthy, manly boys to read; they are neither "ornamented" with vulgar slang, nor loaded up with a preposterous amount of "battle, murder, and sudden death." Indeed, so far is this from being the case, that I would like to claim that they have a distinct educational value, were it not that I am aware that here one must tread lightly, lest young readers should scent suspiciously something of that bête noire of the juvenile mind—the "instructive" story-book.

As a matter of fact, however, there is nothing in the following pages which is not scientifically possible, or which goes beyond what may be fairly termed, the Romance of Science and Natural History.

—The Author

"YONDER lies the so-called island, Mr. Ray. I've brought my ship to the place, and so have fulfilled my part. What's going to be the good of it all is another matter. But there! you've known my opinion of this crack-brained voyage all along!"

"You say 'so-called' island, Captain Warren. Isn't it an island, then, after all?"

"Pooh! You can't call a place an island unless you know there's land there—real, hard, solid land. Now, so far as is known there's no real land here at all— nothing but a great tract of sea covered with tangled vegetation; just a vast, steaming swamp, in fact. Ye may sail round and round it, and ye'll find it everywhere the same; and you may struggle into it— as far as you can, and that's not far—and ye'll find it all just the same—no sign or trace of dry land can you actually touch, so to speak. In the distance, 'tis true, you can see something which may be rising ground—but you can't get near enough to make quite sure."

"How far have people penetrated into this swamp, then?"

"Oh, not very far—you can't get far. This marine growth is too dense to allow any boat to navigate it. No ship dare sail into it, while as for a steamer, well, of course, her propeller'd get tangled up in no time. Between you and me, Mr. Ray, I should have thought that a matter-of-fact, hard-headed scientist, as Dr. Strongfold is supposed to be, would have had more common sense than to bring us all sweltering here into the tropics on a wild- goose chase o' this sort!"

"H'm! Well, the doctor's keen on exploring unknown regions, as you know, and so—But there!

what does it matter? We've only come on a cruise, after all; and we had to do something to pass the time until my father comes back!"

This talk took place on board the steam yacht Kestrel, then on a cruise in the Southern Seas, and the two speakers were Marcus Warren, the captain of the vessel, and young Raymond Lonsdale, son of the owner.

A tanned, grizzled, tough old veteran of the sea was Captain Warren, but in his steady grey eyes there was a glint of good- nature to be seen mingling with the shrewd, albeit somewhat stern, glance habitual to them.

His companion, Raymond—or Ray, as he was usually called—was a good-looking English lad, well grown, with broad shoulders and sturdy, muscular limbs which told of athletic training, a sun-browned face, and general gait which suggested experience of the sea, and of an outdoor life generally. And so it had been with him; he had already seen a good deal of knocking about, for he had lived much of his life on board the Kestrel. On her he had already met with more than one lively adventure, too, for his father had been mixed up in some of the civil wars which break out now and again among the restless states of South America, and had taken part in some pretty stiff fighting.

Tiring of this, and finding in it neither glory nor profit, Mr. Lonsdale had gone for a voyage in the Pacific, and finally to Australia, where at Sydney he got news of some newly-discovered gold region, and started off upon an expedition into the interior to investigate.

Ray had been left with Captain Warren and another friend of his father, Dr. Strongfold; with leave given to pass away the time in a further cruise in the Southern Seas if they wished it.

Then it was that the worthy doctor resolved to try to see something of a mysterious island of which he had been told, where, it was said, had been seen some very strange people. They were declared to be a race who had lived so long among the tangled vegetation of dense swamps, and passed so much of their time in the water, that they had developed webbed feet and hands, and become a sort of half men, half frogs.

"Travellers' tales, my dear sir, mere travellers' tales," Captain Warren had declared, contemptuously, when the doctor had unfolded his plans, and asked him whether he thought he could take the Kestrel to the island, and give him the chance of discovering some members of this wonderful race. "Of course I can take you to the island—it lies not a great way from New Guinea, and I have myself already sailed round it, twenty or twenty-five years ago. But you can't get beyond the outer fringe of it—no one has ever yet succeeded in penetrating the miles upon miles of swampy vegetation—and as for any 'freaks' of the sort you've been told of —Pooh! such ideas are travellers' tales—the sort of thing, in fact, which we keep on board ship to be served out specially to the marines!"

However, the doctor's scientific curiosity had been aroused, and in the end he had prevailed upon Warren to take the vessel in the direction of the mysterious island, instead of going, as had at first been intended, on a cruise to New Zealand.

So here they were, in due course, in sight of "Doubtful Island"—as the place has been called on some old charts—and Ray, taking up a pair of powerful glasses, stared through them for some time without speaking. Then he put them down with a disappointed air.

"Certainly the place doesn't look very promising, Captain Warren," he said. "As you say, there seems to be no sign of dry land. One can understand now why they have called it 'Doubtful Island.' I am sorry, for—well, I expect you know without my telling you—I was looking forward to some adventures in exploring an unknown country."

"For the matter of that," said the captain in a low voice, "I'm not so sure but what you may have an adventure yet—if ye mean fighting. Not very far away, on t' other side, there are some islands inhabited by a lot o' swabs—vile cannibals, every one of 'em; and for some reason or other they're fond of coming over and hanging around 'Doubtful Island.' What their little game is I don't rightly know. Some say that they come for fish; others that they find here amongst the swamps some curious big lizards which they kill for the skin, which is supposed to be harder and tougher than crocodile skin. May be so, may be not. But I've got some notions of my own about all that."

Ray looked inquiringly at the speaker. In his manner, more than in his words, there was a suggestion of something mysterious which roused the young fellow's curiosity.

"What do you mean, captain?" he asked eagerly. "What are the 'notions' you hint at? Tell me what you mean—I'm dying to know."

"Well, perhaps it's better you should know, Mr. Ray," was the answer, spoken in serious fashion. "In fact I was going to tell ye on the quiet that I want you to keep a sharp look-out all the time we're in these waters—as sharp as ye can without exactly letting anybody notice. D'ye understand?"

"Why no, I don't," returned Ray, frankly. "Whatever are you driving at, captain? Who is it I am not to let know? The doctor— ?"

"Oh no! I didn't refer to Dr. Strongfold, o' course. Only it's not much use speaking like that to him—he is too abstracted and careless—too much taken up with his scientific hobbies, and— "

"Ay, aye; I quite see that. But who, then—of whom are you afraid?"

"Pooh! I'm not afraid of anybody, of course— specially with a ship like the Kestrel, in which I've had many a stiff fight— aye, and have beat off much bigger vessels, too, as you know— "

"And we are so well armed, too," Ray put in. "What can there be—or who can there be—about here to be afraid of?"

Ray looked thoroughly puzzled. It has been already hinted that the Kestrel had seen some fighting. As a matter of fact, though ostensibly a private yacht, she had been built and fitted out almost as a gun-boat; and she carried a very formidable armament, though it was so artfully hidden away, when not required, that there was little trace of it to be seen by any save a very keen observer.

"'Tain't that, lad; 'tain't that," answered the old sea dog, shaking his head. "Of course I know we can fight anything or anybody we're likely t' have to fight in these seas, if it comes to fair fighting. But they do say—there are rumours—dark stories—a bit wild and vague too, yet possible enough—of ships having mysteriously disappeared in these waters. What's become of 'em nobody knows; no trace of the ship—no survivor—nothing's ever come to land to explain. The place is a veritable mystery of the sea. The only reasonable theory is that the missing vessels may have been surprised by a lot o' these cannibal natives, with their swarms of canoes—swabs who'd loot an' burn the vessel, and then dine off the people on board her."

Ray shuddered. "I begin to catch your idea, captain," said he. "But so far as we are concerned, of course, the only thing we have to fear is a surprise?"

"Yes—and no," Warren answered, dubiously. "Ye know that we lost some of our best hands at Sydney; these rumours of fresh gold discoveries got hold of 'em, they got the gold fever and went off. And the chaps I had to take on in their places are a muddle-headed lot—if there ain't worse among 'em. I wouldn't trust to 'em to keep a proper sharp look-out at night, an' that's why I give ye the hint. So keep your eyes open, Mr. Ray, and help me to keep a sharp lookout, especially at night—an' more especially still if ye see any suspicious canoes hovering about. Even one or two may mean mischief, because there may be swarms more skulkin' out o' sight close at hand. This swampy region we're nearing is just the place for the cunning beggars to hide in an' to help 'em bring off an ambuscade business. See?"

"Yes! I quite see now, captain; and you may rely upon my keeping my eyes open and my wits about me," replied Ray, promptly.

"And I have taken my precautions and laid my plans," Warren declared finally. "My oldest and trustiest hands have been warned and told exactly what to do in case of anything suspicious being seen; so now we can end our little talk, and if you like you can fetch the doctor up. He's dozing in the cabin, I guess. I expect he'll like to know we're nearing the place where he hopes to find his wonderful frog-men."

With a cheery laugh the skipper went off towards the bow, while Ray went to tell the news to the scientist.

Five minutes later he returned to the deck; accompanied, this time, by Dr. Strongfold. The doctor was about fifty years of age, stout but active, florid of complexion, with a sharp keen eye, which, however, had in it, latent if not always openly expressed, a certain quiet, good-humoured twinkle.

"At last, Ray, my lad, at last!" he cried, enthusiastically, as he patted his young companion on the shoulder. "At last we shall see whether I've been rightly informed!"

"I've never been able to make out yet who 'twas gave you the information, sir," Ray observed, with a suggestion of reproach in his tone.

"Because I was made to promise I wouldn't tell," said the doctor. "My informant made that an important condition, and having promised, of course I've kept to it. However, you shall know all in good time. We shall be able to put the matter to the test very soon

now—and then—"

"Then we shall see what we shall see, doctor," laughed the captain, who had just joined the two. "Well! There's your precious island, sir. What d'you think of it?"

Apparently the savant did not think very much of it, for, like Ray, he first stared through the glasses and then put them down with a distinct suggestion of disappointment.

"Goodness!" he exclaimed. "Why, it looks like merely a vast expanse of floating sea-weed, with a lot of driftwood mixed up in it. Call that an island—"

"I never called it an island," Warren reminded him. "Very much the other way."

"Humph!" The worthy doctor looked somewhat gloomily forth over the conglomeration of weed and driftwood which was all that was visible. Then he took out a pocket book, opened it, and drew from it a sheet of paper.

"Upon the south side, near the south-eastern corner, is a sort of bay," he said, reading from his notes, "and there will be found a wide channel running up into the swamp—a channel, apparently, which was originally that of a wide river, but which has become greatly choked by vegetation. Eh?" He looked up sharply, as he caught a chuckle from the skipper.

"I shall be greatly choked in a minute," Warren exclaimed, with difficulty swallowing down his inclination to laugh. "Why the whole place is 'choked with vegetation'; any one can see that! May I ask where you got that valuable prescription, doctor, and who wrote it out?"

"Never mind," the scientist replied, good-humouredly. "I've given you the prescription—it's for you to make it up. Find me the south-east corner and the bay, and then we'll get out a boat and look for the channel."

With a shrug of the shoulders, as who should say, "I wonder what the next nonsense will be?" the captain went to the compass to consult it, gave some orders to the helmsman, and an hour later brought the yacht up in the middle of a deep bay. Here— greatly to his surprise—he discovered there was a good anchorage.

"Why, whoever would have thought it!" he cried. "I never knew there was an anchorage in this miserable, world-forsaken place."

The doctor rubbed his hands.

"Shows my informant knew what he was talking about, anyway," he remarked, blithely. "Now, captain, please let a boat be got out, and pick me a good crew. Let 'em bring rifles and revolvers—and—ah—let Shorter be one of 'em."

The captain gave a scarcely perceptible start.

"Shorter!" he repeated. "Why Shorter?"

"Never mind now; I want him with me," said the doctor, quietly.

Ridd Shorter, as he was called, was one of the new hands the captain had referred to in his talk with Ray—one of those recently taken on at Sydney. He was no favourite with his officer, but the skipper acceded to the request with a half- muttered protest.

"You seem to 've taken a great fancy to Shorter doctor! I'd rather you kept to our old hands! However, of course you can take him if you choose."

Ray got into the boat with the exploring party, and an hour later they found the channel as predicted by the doctor, and entering it, soon lost sight of the ship.

"There must be land, or those trees couldn't grow as they do," observed the doctor, pointing to the banks on either side. "Ha! What is it, Shorter?"

Ridd Shorter was pointing to something in the distance. It looked like a canoe moored to the bank under a dense mass of foliage. The boat's course was altered, and she presently drew up beside the bank. There, close to her, was a very old-looking canoe, half on the bank and half in the water.

"There's something lying in the bottom," cried the doctor, as he stood up to get a better view. "Why, it's—it's—"

"It looks like the dead body of a man—the body of a native," said Ray, as he, too, stood up and peered into the craft. "Why, it seems quite dried up—a mere mummy!" he went on, in astonishment.

The doctor had already sprung ashore on the marshy bank, and reached the side of the canoe. He bent over the queer form lying in it, touched it, moved it a little; picked up one of the dried- up, withered legs, and dropped it again.

"Yes!" he said, in a tone half of awe, half of triumph. "You are right, Ray, as to its being a mummified body of a man—but—it's a man with webbed feet!"

"It's a man with webbed feet!"

AN hour later, just before sunset, the boat with the exploring party returned to the ship, towing behind them the canoe with its grim occupant.

The skipper's face was a study as the men hauled the relic on board.

"Handspikes and fishhooks!" he exclaimed. "What in thunder 've you got there? Is it a new kind of fish?"

"It's a 'find,' captain," said the doctor, rubbing his hands. He was greatly elated at this early success—doubly pleased, in that it was not only a remarkable scientific discovery in itself, but it enabled him to turn the tables, so to speak, upon his friend the skipper. For the sceptical man of the sea had chaffed the man of science unmercifully throughout the voyage, losing no opportunity of declaring his frank disbelief in the existence of the "men with webbed feet." And now, lo! behold! the doctor had scored by capturing a specimen at the very first attempt!

"It's a great 'find,' a grand find!" continued the doctor. "Ha! what will they say in England when I lecture on this at the Royal Institution?"

"Harpoons and codfish! It beats everything!" muttered the old mariner, as the scientist pointed out the webbed feet. "Blow me up with a sky rocket, if ever I'd 've believed it!"

Dr. Strongfold carried off his prize to the little cabin which he had been allowed to use as a sort of combined laboratory and "mounting" room. Here he was wont to dissect and "mount" all sorts and kinds of queer, out-of-the-way zoological and entomological specimens. He had already got together a fearsome and awe-inspiring collection—or so the wondering sailors considered it—but there was nothing amongst the whole accumulation of monstrosities to equal this last addition.

Later on, when walking to and fro upon the deck with Ray, smoking his pipe, under a light awning which shaded them from the rays of a half-moon high overhead, the skipper showed himself to be a bit puzzled.

"Seems a little queer, ye know, Mr. Ray, this grand find o' the doctor's. I wouldn't like to say such a thing to him—but, to my mind, ye see—hum! well, it's a rum go!"

"Very remarkable, captain," assented the young fellow, who was frankly delighted at the doctor's unexpected success. "What a noise it will make at home when all the big-wigs come to hear about it! There'll be lots of articles in all the papers, and they'll be talking about the Kestrel's cruise as a voyage of scientific discovery, and we shall all—"

"All have our names in print," the old salt interrupted, somewhat testily. "Pooh! I'm not thinking about that! Of course I'm glad for our good friend the doctor's sake—but—" Then he broke off, sniffed discontentedly, and gazed in gloomy silence out over the moonlit sea.

"Then what is it you're thinking about, sir?" Ray asked, looking at his companion in surprise.

Warren remained for a space staring straight before him without speaking. Presently he passed a hand across his forehead, as though he were trying to brush away some confusing thought that was worrying him. Then he took a seat against the bulwark, and motioned to Ray to do the same; looked round to make sure that no one was listening, and resumed the talk, speaking in low, cautious accents.

"It's this way, Mr. Ray. I'm a rough old sailor, as ye know, and am little given to fancies, or sentiments, an' that sort o' rubbish; but I do confess to you as I am bothered with a sort o' feeling that something's in the wind more than you and I are aware of."

"A—a—why, not—not—a presentiment, Captain Warren?" Ray stared in astonishment, as well he might, for he knew that the skipper was usually about the last man in the world likely to confess to such a weakness as a "presentiment."

"I dunno anything about presentiments," Warren answered, a little shamefacedly, "but I've got a sort of idea that things are not right. This grand discovery of the doctor's has come about a little too easily—looks a little too much like being all 'as per programme,' if you can understand." He paused as if in perplexity.

"But—I can't see how. I'm sure I can't make out your ideas, captain."

"Nor can I myself—not to my own satisfaction," Warren admitted. "However, let me put it another way, then p'rhaps you'll see my drift. This thing you came upon so pat and brought back with you this afternoon—you were hardly gone a couple of hours— this mummified frog, or froggified man, or whatever it is—how long d'you suppose it'd been lying where you came upon it?"

"How long?—oh! I'm sure I've no idea. How can I tell?"

"Well, it couldn't have been long, could it? In this region— here, almost under the equator—things of flesh an' blood don't be about long before something happens—do they? even if, as the doctor calls it, mummified?"

Ray assented to this proposition.

"Well, you know the whole thing has a sort of 'got up' look. The canoe is old, dried up, rotten; the body is dried up, too, same as if some one had put 'em there like that to give the idea they'd laid there for a long time—months—years. Yet we know that's impossible. Ants, alone, would 've found the thing an' ate it up in no time; to say nothing of other creatures. Therefore it must 've been put there very recently—yesterday—p'rhaps to-day. The thing didn't put itself there: an' it didn't die accidentally and dry up like that?"

"No; I suppose you're right."

"Then somebody put it there just as if they knew you were going to look for it—and not long before we arrived here; just as if they had sighted the yacht coming and had been waiting ready."

"Im—possible!" exclaimed Ray, drawing a long breath. "Why! to suppose that would be to suppose—oh! all sorts of impossible things, Captain Warren!"

"So it seems—at first sight—but—somehow—By the way, who really found the thing? I mean, who led the way to it, or who first caught sight of it—you or the doctor?"

"Why—h'm—neither, I fancy," answered Ray, rather confusedly trying to carry his thoughts back to what had actually occurred. "It was—yes—it was Shorter who first caught sight of the canoe as it lay under some trees. And he pointed it out to the doctor."

"Ah!"

It was all the captain said. After that he remained silent, puffing vigorously at his pipe and staring straight before him. Nor did he resume the talk later on, but got up, after a brief space, and walked away without another word. Yet there was a suggestion of so much hidden meaning in the one word he had spoken, that Ray opened his eyes and gazed at the skipper with looks of something very like amazement.

Then the doctor came on deck, full of enthusiasm, and brimming over with scientific information concerning the examination he had been making of his "find." Nothing more, however, was said that evening upon the part of the subject which seemed to have so interested the worthy captain.

"We'll turn in early to-night, lad," said the doctor, at last, as he caught Ray trying to stifle a yawn. "I'm going to start in the boat again early in the morning to make a further exploration. This time we will go prepared to carry our quest much further, even to camp out for a night or two if needs be. I feel sure that that channel extends a long way. It may even lead us into the interior."

"Strange that such a channel should exist and never been discovered before," murmured Ray, sleepily. "Captain Warren declares that years ago he sailed clean round the whole place, searching for something of the kind, and that he could not see a trace of it."

"That may well have been the case at that time," returned the scientist. "I noted many signs, to-day, tending to show that this opening has been made recently—that is, within the last few years. I am inclined to think there are volcanic forces at work in the interior, and something must have burst its barriers, as it were, and rushed down, breaking through the tangled growth, and so opening a way to the sea. However, we'll turn in now so that we can be up the earlier in the morning. You'd like to come with me, Ray?"

"Very much indeed, sir. Will Captain Warren come, too?"

"No; he says he will not risk leaving the vessel, though what he's afraid of I can't quite understand. One would almost think that after pooh-poohing my web-footed men all along, he had been induced, by our find of to-day, to believe that the whole region is alive with 'em, and that he fears they will make a descent on the yacht in their thousands, while he is away."

And laughing genially at the fancy thus called up, the doctor sought his bunk.

Ray sought his, too; but he could not sleep. Something in the captain's manner had oppressed him with a vague sense of hidden danger. At last he got up and crept silently on deck.

There he found the skipper pacing tirelessly and noiselessly up and down.

"Are you not going to turn in, sir?" he asked, in surprise. "Aren't you going to get some sleep; you must be as tired—"

"Not now," returned the skipper, almost in a whisper. "Not here. While we remain here I prefer to get what sleep I want in the day time. However, that's nothing to do with you, my lad; so off you go back to your bunk again!"

Thus urged, Ray obeyed; and this time he got to sleep.

IT has been said that Ray at last got to sleep, but if the truth be told it was a sleep disturbed by some queer, wild dreams, in which the grotesque and the gruesome were strangely intermingled.

For instance, he dreamed, at one time, that they were all back in England, where the country was ringing with the noise of their discoveries, and with praises of their exploits in the now famous Kestrel. Crossing Trafalgar Square, he saw the whole side of the National Gallery covered with a gigantic poster on which was his own name in letters reaching from the roof to the ground. Turning from this, he perceived a crowd around a colossal monument standing in the place which the well known fountains used to occupy. Wondering as to what they could be gazing at so reverently, he glanced upwards, and lo! there was a statue of himself, in "heroic" size—and something more—dressed in the uniform of an Admiral of the Fleet. But as he looked, he noticed that one eye of the statue was closed, as if winking, and that one hand pointed downwards. Following the direction of the pointing finger, he saw, to his horror, that this amazing statue of himself had webbed feet!

As he cast a glance down towards his own feet, to make sure that this was not a true representation of his lower limbs, he perceived that he was in evening dress; and just then some one took him by the arm and urged him onwards. "They're waiting for ye, Mr. Ray," said a voice, which he recognized as that of Tom Waring, the first mate of the Kestrel. Inquiries, as they hurried along, elicited from Tom—who was also in evening dress— the information that he (Ray) was overdue at Burlington House, where the King and the President of the Royal Geographical Society were waiting to hear his promised lecture upon "The Dried Frogs and Mummified Toads of Doubtful Island." When, however, they reached the place, he found that it was a ball-room, and the assembled guests were waiting for him to lead off in the first dance.

Immediately he arrived, he was seized upon by His Majesty on one side, and the President of the Royal Society on the other, and they all joined hands and danced wildly round in a circle, in which were the Prime Minister, Captain Warren, Dr. Strongfold and others; while, as he whirled about, he noticed that Ridd Shorter was playing the big drum. Suddenly the latter gave a tremendous thump, which seemed to be a sort of signal, for immediately those around him let go hands, and each began dancing a hornpipe on his own account. Louder and wilder grew the music, and faster went the legs of His Majesty, the President, the Prime Minister, and all the rest, as with folded arms and perspiring faces they tried to keep up with the ever-increasing speed of the music. Then Ray looked down, and behold! they all had bare, webbed feet; of which, however, they seemed particularly proud, for they were doing their best, as they danced, to draw the onlookers' attention to them and show them off!

At that moment there came a louder bang at the drum, and a crash as if Shorter had jumped on it and fallen through—and Ray woke up.

"They're waitin' for ye, Mr. Ray," said the voice again—the same voice he had heard in his dreams.

"Where am I to go now, Tom?" Ray asked, wearily. "I'm about tired out! I tried my best to keep step with His Majesty, but he went too fast for me—"

"The doctor's waitin' for ye, Mr. Ray."

Ray sprang out of his bunk and stared at Tom Waring, the mate.

"You—why—you're not in evening dress, Tom!" he spluttered; and then he looked down at his feet. "Are your feet all right, Tom," he asked, anxiously, "or have they turned to webbed—"

"Ye're not awake yet, sir," grinned Tom. "But ye'd better make haste, or the boats 'll go off without 'ee."

Then Ray perceived that he had been dreaming.

"Wait half a jiff, Tom, and I'll be ready," he cried.

"I'm goin' too, to-day; cap'en's orders," Tom remarked, while waiting. "Special service—to look after you."

"After me?" Ray asked, wonderingly. "Why after me in particular?"

"Dunno! cap'en's orders! Says he's goin' to look after th' ship, an' I be to look after you."

A tough-looking old son of the sea was Tom Waring, with his grizzled beard sticking out from his chin in a fashion which seemed half saucy, half a challenge, so to speak, to all and sundry. Honest and trustworthy to the core was Tom; and the captain knew it. And since the skipper could not be with his ship and with Ray too, he had decided upon what he considered the next best thing—to send his trusted mate with the boat party.

"An' take care ye look after the lad, Tom, an' don't ye trust him out o' your sight—specially in company of Sh—, of any of these new hands we've taken on," he growled. "Don't you forget that I'm responsible for the lad to his father. If anything happened to him, how'd I ever look Mr. Lonsdale in the face again?"

"Or me, either?" Tom assented.

"Oh you—if you were to come back without the lad you'd never be here to see his father."

"Why not, cap'en?" Tom inquired, innocently.

"Because I'd string ye up at the yard-arm," was the startling answer.

But the threat did not anger honest Tom. He and his chief understood one another. Many were the fights they had seen together, many were the "tight corners" they had been in together; many were the times each had been indebted to the other for his life—more times than they could count. At heart they were the closest of friends—though at times, before the sailors, Warren would find fault with his mate and swear at him roundly.

"Cap'en don't mean nothin'," Tom would say at such times, philosophically. "It's all done for effeck! It has a good effeck on the others!"

The boats sailed away—there were two of them this time, one being laden with provisions, tents, and camp equipage—and the breeze being favourable, they soon passed out of sight of the ship, and made the channel, where there was still enough wind to take them at a steady rate against the gentle current flowing down towards the sea. As they went on, the waterway opened out, the banks were farther apart, and low rocks appeared, which gradually became higher and bolder in shape till they took the form of cliffs and low, rugged-looking hills.

Presently the explorers could see, through a haze, the outlines of distant mountains.

"I think we'll make a mid-day halt here and wait for the cool of the afternoon before going further," said the doctor at last. "On the shore, yonder, I see a stretch of greensward with a stream tumbling from the rocks, and beside it a shady grove. That should make a good camping ground, I'm thinking, where we could pass the night if needs be, after we've explored the neighbourhood."

The boats were steered to the bank, and a good landing place having been chosen, the doctor and Ray, with two or three men, took up their arms, and went to reconnoitre, before landing more of their party.

It was a wild, gloomy-looking spot they had chanced upon. Great masses of rock were piled about in picturesque confusion, while at the end of the valley, steep cliffs, many of them covered with thickets of dark-looking trees, rose one behind the other, frowning down upon them and seemingly completely shutting them in. Near the shore, however, was a flat stretch of green upon which was the leafy grove which the doctor had descried. Through this, beneath the welcome shade, tumbled and foamed a small stream which issued from the rocks beyond and finally found its way across the green, meadow-like flat to the shore. Except for the sombre, forbidding aspect of the towering rocks in the background, however, the spot seemed in many respects an ideal camping ground for the hot and thirsty travellers.

"No sign of any inhabitants," decided the doctor, after a careful look round.

Nor had they seen any evidence of human occupation on their voyage up the broad waterway. There had been ample signs of almost every other kind of life. Through his glasses Ray had scanned the banks on either side, and had noted that the region teemed with living creatures. Crocodiles—some of immense size— were to be seen basking in the mud or crawling sluggishly up the banks; flamingoes, in flocks, were fishing in the pools on the shore; herons and cranes abounded, and gaudily- plumaged parrots screamed and darted to and fro amongst the trees. Palms and great tree-ferns were growing here and there in luxuriant profusion, while eagles, vultures and other big birds of prey were constantly met with, hovering overhead, as if meditating a swoop upon the boats and their venturesome occupants. Every now and then they disturbed flocks of wild swans, ducks and other waterfowl, which rose in the air with a sudden startling whir, and circled noisily round and round ere finally taking themselves off to other haunts. None of these, however, had been shot at by the travellers.

"Best not to attract the attention of possible inhabitants by firing just now," the doctor had decided. "Evidently there is plenty of game about, and we can get it whenever we want it later on."

"The place is just a hunter's paradise," said Ray, with a half-regretful sigh. "But I dare say you are right, sir, and it's best to be cautious; though so far as one can see there is no trace of human beings—web-footed or otherwise," he added, with a glance at the doctor. "And that makes it the more extraordinary that we should have come across what we did yesterday."

"Time will show; we must be patient," the scientist answered.

And now that they were on the shore and could examine the ground around them more thoroughly, there was still no sign or trace of human inhabitants; and the doctor, having satisfied himself as to this, gave the order to bring the tents ashore. A few minutes later the sailors were busily engaged in landing the tents and some of their stores, and setting out their camping ground.

After a meal and a brief rest, Ray gained permission to go out with his rifle to see what he could shoot for their evening meal. The doctor deputed one of the sailors named Gale to accompany him, saying that he and Tom Waring would follow a little later.

"Don't go far, and if we don't catch you up, wait about for us," said the scientist. "I think we had better make up our minds to remain here for tonight at any rate, so there is no hurry. I will catch you up after I have settled all arrangements here. If you don't see us soon, fire two shots as a guide."

Matters being thus arranged, Ray and his companion started going inland up the valley, and were soon lost to view behind the great boulders which were strewed about in all directions.

Jim Gale was one of the yacht's regular crew. He was, moreover, a great chum of the first mate. Waring felt, therefore, that he was in no wise breaking the trust Captain Warren had given him in letting his chum accompany the lad, instead of himself, until he and the doctor should catch up with them.

So the two made their way up the valley, Jim, a young sailor endowed with an inexhaustible fund of high spirits, evidently entering with gusto into the adventure.

"My father were a hunter in the backwoods of America," he informed Ray, "an' I saw a lot of trappin' an' shootin' with him afore I turned sailor. It's a'most like old times to turn out again wi'a rifle in yer hand, and t' see a place wi' plenty o' game about, like this."

"Yes; I can understand that," returned Ray, sympathetically. "And certainly there seemed to be plenty of life as we came along; though just here," he added, looking round in some surprise, "we seem to have dropped upon the one spot where there is nothing to be seen!"

They went on a little further, and then climbed a low, rocky eminence, from which to get a better view of their surroundings. Again the outlook was disappointing. All they could see was a wilderness of rocks strewn about in endless confusion, with here and there dark gullies and caverns, and amidst it all numerous solitary pools, or small lakes, of stagnant water.

"I think we'd better turn back, Jim," said Ray, as he gazed round with a sort of shiver. "We can meet the doctor coming up and advise him to try another direction. There is evidently no game here of the sort we want; though, perhaps, it might make a good hunting ground for snakes, and lizards, and small deer of that kind. Ugh! It gives one a dismal, uncanny sort of feeling! Great Scot! what's that?"

A shriek had rung out and echoed from rock to rock. The two started and loosened their rifles which, in full expectation that the place was uninhabited and that there was nothing worth shooting at, they had now slung at their backs.

Ray peered about on all sides, but could see nothing to account for the sound they had heard.

Suddenly it rose again—the long, despairing cry of one in mortal dread, or terrible danger. Yet still nothing could be seen to account for it.

Gale pointed to a part of the edge of the cliff fifty or sixty yards away from where they were standing.

"Sounded to me as if it came from below the edge there," he said, in a low voice.

"We'll go and see," Ray returned; and they hurried at once to the place and looked over. A strange and terrible sight met their gaze.

Immediately below them they saw the dark waters of a large pool, with steep, rocky sides, upon which, here and there, grew a few scrubby bushes.

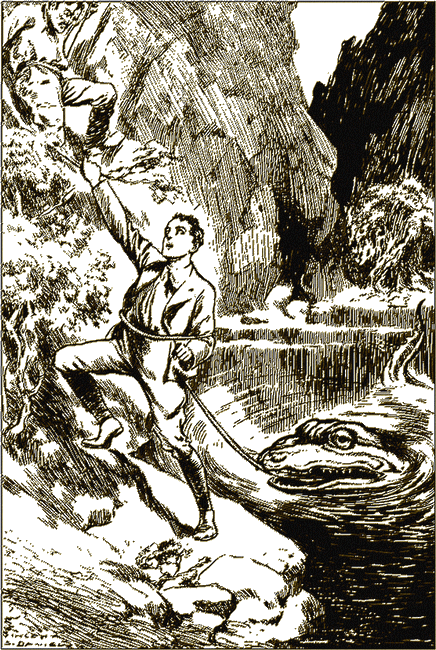

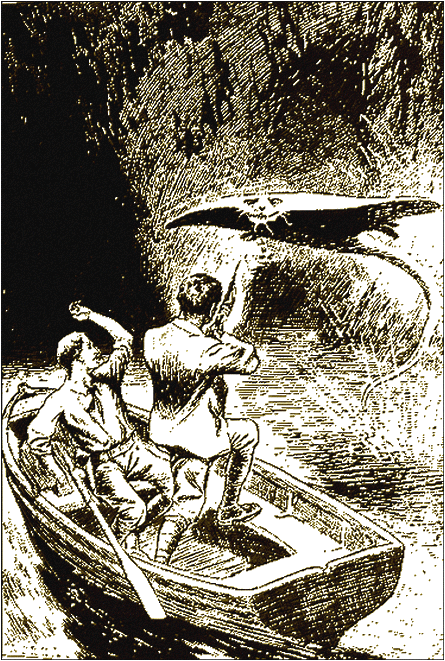

Clinging to one of these bushes was a man, who held on desperately with one hand and arm, while with the other he seemed to be trying to free himself from what the onlookers at first took to be a rope or lasso which had coiled round his body. Tracing this "rope" to its origin, they saw, to their astonishment and horror, that it proceeded from the open jaws of some great monster in the pool. Only the head could be seen, but a commotion in the surrounding water suggested that the creature was of considerable length, and that a great tail was lashing the surface of the pool several yards behind it.

The rope proceeded from the open jaws of a great monster.

Although they could not understand the exact situation, the two spectators saw enough to grasp the fact that the man was being attacked by some terrible reptile and was in deadly peril, and they both fired at the great green eyes they could see glaring just above the water. Instantly the "rope" vanished, and the man was free, and a moment later the monster vanished also, disappearing in the pool's sombre depths with a great splash and a mighty swirl of the water.

The man looked up and feebly waved a hand by way of acknowledgment, but he seemed either to be badly injured, or too dazed and exhausted by his struggle to be able to climb the steep bank out of further danger.

The two above shouted to him, but he seemed not to hear.

"I believe he's fainted," Ray exclaimed. "What on earth can we do? One of us must go down to him," he declared, laying his rifle aside. "And it had better be me, because I am lighter than you."

To this Gale at first demurred, but finally gave in in view of the consideration that he, being the stronger of the two, would be more useful at the top when it came to hauling on the line.

Ray had seen a good deal of hunting in South America, where he had learned the use of the lariat, and he had taken the precaution to bring one with him, coiled round his body. This he quickly unwound, and having fastened one end round his own body, he gave the other to Gale, who tied it to his waist and then lay down full length, with his arms over the edge of the rock, and prepared himself to assist the other's descent.

The lariat was of hide, very tough and strong, and Ray descended by its aid, climbing downwards where the nature of the rock allowed, and in other places trusting to the line alone. In this manner he reached the stranger, whom he found, as he had expected, in a fainting condition. Taking out his flask he poured some brandy into the man's mouth, and had the satisfaction of seeing him revive. A few moments later he roused up from his lethargy and seemed to begin to collect his scattered wits.

He was a dark-skinned, beetle-browed fellow, by no means prepossessing either in appearance or manner. When spoken to he answered in English with a Portuguese accent, and Ray put him down in his mind as a "Dago," in which, as it afterwards turned out, he was right.

Having given him time to rouse himself, Ray signified that it was necessary to make an effort to get out of their present situation; and finally he fastened the end of the lariat round the fellow's waist, and urged him to try to climb with its aid, while his sailor friend hauled from above.

Suddenly, he heard again that ominous swirl in the water behind him. He made a move and looked round, and instinctively grasped the bush nearest to him, the same—as it chanced—that the man had clung to.

Ere he could turn, however, something swept up and pinioned his arm to his body—something like another lariat, save that it was cold, slimy, sticky. Looking downward he now saw the gleaming eyes of what looked like a gigantic lizard of most hideous aspect. It was the long, flexible tongue of this creature which had shot out and wound round his body, and Ray realized that he was himself now in the same peril as that from which he and his companion had rescued the stranger.

IN the meantime, many feet above, Jim Gale looked down upon the scene and almost froze with horror as he looked.

His rifle lay on the ground out of reach behind him, and both his hands were employed in gripping and hauling at the line, the while that Ray was struggling in the coils of the frightful monster below.

The honest sailor realized, in that terrible moment, that if he released his hold and reached for his rifle, the stranger would fall and slip back into the very jaws of the creature waiting for its prey. Possibly, that might save his friend, but it looked like sacrificing the stranger in a very cold-blooded fashion. On the other hand, if he held on to the line, he could do nothing to aid Ray, whose fate would then be sealed.

What was he to do?

The solution of the problem came from an unexpected quarter.

There was a sound of firing, the great reptile of the pool again gave up its intended victim, and disappeared, with a tremendous plunge, beneath the water.

"Let go of the line an' leave it t' me, Jim," said the welcome, hearty voice of Tom Waring, and Gale was glad enough to relinquish his rescue work into other hands.

"Whom have you got there?" Dr. Strongfold now asked. He had heard the two shots just as he had been coming out of camp accompanied by Waring, and had hurried on in the direction from which they had seemed to come. Luckily, the two had chanced upon the scene just in time to rescue Ray and relieve Gale from the difficulty in which he had been placed.

"Goodness knows," the latter now replied, in answer to the doctor's query. "Some chap who was in the same plight you saw Mr. Ray in. Mr. Ray went down to help him, and got caught himself. I'm thankful you came up when you did, sir."

"So am I, my lad. What was the creature in the pool?"

"I saw no more of it than you did. Seemed to be a sort o' monster lizard, with a wonderful sort o' long tongue."

"Humph! Well, here's the stranger brought to bank, as the miners would say. Now to help Ray to make the ascent."

In two or three minutes more Ray was also safely back amongst his friends.

"Before we talk we'd better get back to the camp," the doctor counselled. "Come along, friend," he added, turning to address the stranger. "You can give us an account of yourself, and how you came to be here, over a cup of coffee, which we shall all be glad of, I expect."

Later on, when they had reached their camp, the doctor questioned the man first as to his presence on the island, and afterwards as to his adventure at the pool.

He answered glibly enough, that his name was Pedro; he had been cook on board a vessel supposed to be engaged in ordinary trading amongst the islands, but, in reality, carrying on what is known as "black- birding"; which is only next door to slave hunting. When he discovered this, the honest Pedro declared, with a great show of virtuous indignation, he had quarrelled with the skipper over it, and, in revenge, that unscrupulous "trader" had set him ashore on this island—believed to be uninhabited—and left him there.

"What! put you ashore as far from the sea as this?" Dr. Strongfold asked.

"Yes, Excellency."

"Humph." The doctor looked at Ray and said in a low tone, "Then this open waterway, leading up through the swamps, must be known to others besides ourselves." Then, turning to the stranger, he resumed his cross-examination.

"You were marooned, in fact?" he observed.

"Exactly, Excellency," replied the ex-cook. "I have lived here alone for two months."

"Goodness me! And you had no arms to kill any game with! Yet— you don't look exactly starved, you know."

"One finds here many turtles, and fishes—lots of fishes, and oysters, Excellency," was the answer.

"Humph! Well, what were you doing when you were attacked—and what was the creature that seized you?"

As to these points, the "Dago" explained that from the higher ground he had seen the boats approaching, and had hastened down to the shore, rejoicing in the expectation that he would now be able to get away from his island prison. In passing round the margin of a large pool, which lay in his way, he had been seized by some terrible monster, and had been so terrified he had not even looked to see what it was like. He had clung by blind instinct to a bush which happened luckily to be handy, and had in his terror screamed aloud, never daring to hope that there was any one near who could help him.

This brought them to the question of the monster itself, and what sort of a creature it could be. Here Ray was able to give a clearer idea than the stranger. It was exactly like an iguana lizard, he declared, only "a hundred times as big."

"As to the thing that shot out and seized me," he said, "it was the brute's tongue—I could see that, plainly enough. A beastly, long, slender affair, horridly cold, and slimy, and sticky."

"Yes," commented the doctor, thoughtfully; "supposing we admit the existence of a gigantic iguana, it would, in all probability, have just such a tongue as you describe, which it would dart out and seize its prey with. But who ever heard of an iguana of that size—and, above all, living in water! The whole thing is an enigma! Boys, we must capture that reptile wonder! To a scientist its bones would be almost as wonderful a trophy as even a mummified man with webbed feet!"

He ceased speaking abruptly, struck by the flash he had seen in the stranger's eyes at the mention of "webbed feet." The words had slipped from him unthinkingly, and he now regretted the slip; for he did not feel disposed to open his heart to this stranger and tell him exactly what he had come there for. However, save for that one sudden flash, the ex-cook showed no further sign of special interest, but broke out into a long string of protestations of his unbounded thankfulness and undying gratitude to them all for having saved him from a dreadful death.

"Well," at last said the doctor, "if you've been on the island so long, you probably know your way about a little, and could doubtless act as our guide. I am interested in rocks and minerals, and wish to explore the caves of this island. If you desire to serve us in return for what we have fortunately been able to do for you, you can start with us to-morrow morning, and show us the quickest and easiest way to reach the higher parts of the island."

The stranger declared he would be both delighted and honoured to act as guide; and he was then turned over to Waring.

"Find him a shake-down, somewhere," said the doctor; and the mate accordingly led him away, but not caring to have him near himself, allotted him a corner in a tent which had been put up as a shelter for extra stores.

Having attended to this, the worthy Tom sought out Jim Gale, "jes' t' give him a bit of my mind," as he put it. Having found him he led him to a quiet spot a short distance away.

"D'you call this takin' care o' Mister Ray?" he then began, in highly indignant accents. "Cap'en's orders to me was as I was never t' let him out o' my sight. But I sez, sez I, 'I knows Jim Gale, an' l can trust 'im; an' it's the same thing if Mister Ray goes wi' him as if I was there.' Well! an' what comes o' my trustin' ee like that, Jim Gale?"

"I'm awful sorry, Tom, an' that's a fack," Jim declared, humbly. "But 't warn't no fault o' mine. We heard the Dago chap shriek out, an' Mister Ray he insisted on goin' down t' help him. Nothin' I could do'd keep him back."

"Rats!" snorted the angry mate. "Cap'en's order 's got t' be obeyed, my frien'—an' though you're a chum o' mine, dississipling must be kep' up. Cap'en said, if I came back without Mister Ray, as he'd string me up to the yard-arm. You've come very near bringin' that about—a precious sight too near t' please me—an' you must take the consekences."

"Why—what 're you goin' to do, Tom?" exclaimed Gale.

"I'm goin' t' give ye a durned, fine thrashing," Waring declared, rolling up his sleeves. "I ain't got no rope's end— "

Just then Ray's voice was heard calling for Tom, and the next moment he himself came upon the scene.

"I thought I saw you two coming this way," he cried. "Tom, the doctor wants you. We're going to try to catch the monster of the pool," he added, his voice full of eager excitement. Then, for the first time noticing how the two were glaring at one another, he asked, "What's up? What are you two quarrelling about? I can see it's a quarrel! I thought you were always such good friends."

"It's nothing, sir," muttered Tom, as he slowly turned to go. "We've had a hargiment, an' I was jes' about to explain t' Jim what dissiplinating means."

Ray opened his eyes as he puzzled over this lucid explanation. However, he thought it best to take no further notice of the matter, so he merely said,—

"Well, you must leave your argument to another time. The doctor wants you now," and with that he hurried them off to where the scientist was waiting for them.

"Tom, have you got anything amongst your outfit which will come in for fishing on a big scale?" the doctor asked. "I want to catch the creature we fired at up yonder. I mean to have the skin for my collection if it be humanly possible. It would be a unique specimen."

"Ay, ay, sir. I brought our harpoon tackle an' what we goes fishin' for sharks wi' sometimes. I guessed that in these swamps we might see some mighty big alligators as you'd want to bag— though," he added, "cert'nly I never expected to come across a critter like that as laid hold o' Mr. Ray."

"Hurry up then! Get your tackle together and bring three or four of the hands to help—and—er—don't forget something by way of bait."

Half an hour later they were back at the pool and had commenced operations for capturing its uncanny denizen.

THE mate had provided a huge piece of salt junk by way of bait, and this was fixed upon a hook "big enough," as one of the sailors remarked, "to hold a whale." The hook, in its turn, was fastened to a piece of rope which might have done duty for a cable for a very fair-sized vessel; and these formidable devices were backed up by a sort of masked battery—Tom's gun-like tube for firing his harpoon.

The hook, hidden in the piece of meat, was lowered into the water by means of a block and fall suspended, derrick fashion, at the end of a spar run out from the top of the rock overlooking the pool. It sank quietly beneath the surface and there remained, while the angling party gathered round and watched eagerly for the first signs of a "bite."

The afternoon sun poured down with terrific power, heating the arid rocks around until the whole place became like a baker's oven. Ray, after watching till he felt, as he expressed it, "half cooked," crept under the scanty shade of one of the dried-up looking bushes, and there meditated upon the question whether, when they had captured their hoped-for "specimen," it might be safe for him to venture on a plunge in the pool by way of cooling himself. On such a day, even its turgid waters looked cool by comparison.

As no monster showed, and nothing else happened, the general interest slackened; the doctor crept under Ray's bush, and presently began to doze. Waring and the other sailors crept under such shelter as they could find from the sun's scorching rays, and a few minutes later the whole company were fast asleep.

They were suddenly awakened by a prodigious commotion in the waters of the pool. Something was pulling and tugging at the rope with tremendous energy, the water swirled and tumbled, and waves, that were out of all proportion to the size of the sheet of water, splashed and foamed upon the banks.

In a moment the sleepers were on the alert but alas! too late. Ere Waring or any of his men reached the "derrick," the rope had run through the pulley and trailed off on to the bank below, where it wriggled about for a few seconds like a great snake, and then slipped at railroad speed into the water and disappeared. The end had been insecurely fastened, and the "catch" had made off with it—hook, salt junk, and all!

"Bless me!" cried the astonished doctor, as he sat up rubbing his eyes, "Wh—what's become of our rope?"

"Thunder an' soda-water!" roared Waring. "Which o' you lubbers was it spliced that end?"

"What was it?" asked Ray wonderingly. "Did any one see the creature?"

No one had seen it; no one could say what it had been like; no one could even say with any certainty what had happened. The only thing which they were all agreed upon was that they had lost their "tackle." Upon that point there could be no sort of doubt.

"An' the wust of it be as we've no more rope like that piece— an' not another piece o' salt junk," said the mate, ruefully.

The doctor, meanwhile, was scanning the soft ground near the water's edge.

"I fancy I can see some marks yonder which look like the prints made by huge claws," he declared, in some excitement. "I must go down and examine them."

And in this resolve he persisted, despite the objections raised by Ray and the mate.

"There is no danger now," he argued. "The creature that has gone off with that great hook in its throat will have something else to think about than to be coming back to look for another. We have lost our chance of catching it—that is pretty certain. But I can at least measure its footprints; they are by far the largest I have ever seen."

He decided to descend to the water's edge down a steep slope which he had noted. Ray, however, prevailed upon him to put a cord round his waist as a precaution, and a spare length which Waring had with him was brought into requisition for the purpose.

Thus equipped, with a rifle in one hand and his note book in the other, the enthusiastic scientist proceeded cautiously down the slope.

The other end of the cord was safe in the hands of the mate, who, this time, was determined to trust to no one but himself. Ray, meantime, stood watching the descent, rifle in hand, ready to render assistance should occasion arise. The other sailors stood around, keenly interested.

The doctor reached the bottom of the slope without mishap, and found that his surmise had been correct. There, sure enough, were the prints of immense claws, clearly defined in the muddy ground.

He set to work to measure them, after which he made some careful sketches in his note book. Then he turned and began to retrace his steps.

This was somewhat more difficult than the descent, as he had moved along the bank some few yards. Tom Waring, holding on to the other end of the rope on top, felt a sudden tug, and being unprepared for it, was jerked forward a little. Ray, seeing this, snatched up the loose end lying on the ground, and hauled upon it to assist Tom; and at the same moment Jim Gale, perceiving Ray's movement, ran up and also caught hold.

It was well they did; for though the sudden pull upon the line had only been caused by the doctor having slipped upon some loose rocks, something far more serious followed.

Even as he was recovering himself, and just as Ray and Gale had seized the rope above, there again came that ominous swirl in the water, a monstrous head showed above the surface, and from its jaws there shot forth the long, flexible, sticky tongue which Ray had described earlier in the day.

Like a flash it wound round the struggling scientist and began to drag him backwards towards the water—not only that, but the three above were dragged forward two or three paces in spite of all they could do.

Ray's calls, and Waring's more emphatic objurgations, quickly brought some more seamen to their aid.

Then came a lively tug of war—the monster of the pool on one side, and half a dozen sturdy sailors on the other, with the unfortunate doctor between them. At first, it seemed as if the reptile would gain the day—and the scientist; for the first three at the other end—Waring, Ray, and Gale—had already been pulled over the top on to the beginning of the slope, before their companions had come to their help.

"Belay there, belay!" roared Tom to another man, who came running up, and the sailor caught up the loose end, and, instead of wasting time hauling on it, promptly obeyed the mate's order by twisting it round an old stump which happened to be at hand. Tom looked round, saw that the hold was a good one, and then, leaving the rope, made a rush to where his harpoon gear was fixed.

The next moment there was a report, followed by a whizzing sound. Then a cheer went up as it was seen that Tom's aim had been good. The doctor was free, and the great lizard, with the harpoon in it, dived into the pool, leaving the water tinged with its blood. With it went the rope which had been fastened to the harpoon.

"We'll get him yet, lads, if the rope holds," cried the mate cheerily. "Now to get the doctor up!" Ray was already on his way down the slope to assist his friend, aiding his descent by keeping a hold on the line as he went. Waring and Gale now followed, and between them they brought Dr. Strongfold to the top. He was in a very exhausted condition, for in the struggle the breath had all but been squeezed out of his body, and it was found that he had injured his ankle.

He bravely insisted, however, upon remaining to see the issue of the attempt to catch his assailant; but when, a little later, the line fastened to the harpoon suddenly snapped, he resigned himself to the failure of his hopes for that day at any rate.

"It's no use!" he said, with a smile, to Ray. "We'll have to come again another day, better prepared. And now I'm afraid you will have to carry me to the camp, some of you; for I find that my ankle is too painful to allow of my walking back."

A stretcher was improvised, and the injured leader of the party was carried to his tent, where he prescribed cold water applications and rest as the best remedies for himself.

"I must hurry up and get well, for I mean to have that creature yet, and you'll never catch it without me—you'll want me for bait. I made a better bait than your salt junk, Tom, after all," the scientist told the mate, with a chuckle.

THAT night it seemed to Ray very hot and oppressive as he lay in his tent, turning and twisting and trying vainly to get to sleep. At last he could endure it no longer. He took his revolver from under his pillow, where he had placed it when he had turned in, and sticking it in his belt, he softly opened the flap of his tent and stole out.

Clouds were moving slowly across the sky, and between them a half-moon peeped out now and again, sending its beams down through the trees under which the tents were pitched. Ray's tent was the farthest one from the edge of the thicket, and it stood beneath a great tree with dense, bushy foliage, which threw a deep shadow around it.

Into this shadow Ray crept noiselessly, and looked about him. He was surprised to see no one on watch, and was about to move forward, when he fancied he heard a distant footstep. Then he detected the rustle of leaves and the snapping of a twig, and looking round, he dimly made out something which looked like one of the sailors, moving cautiously away from the camp and through the wood.

At once he resolved to follow, and taking every precaution that his previous hunting experiences could suggest to avoid being either heard or seen, he stole off through the wood in the wake of the mysterious prowler.

The latter seemed to have no suspicion of being followed, and went steadily on, keeping always near the margin of the wood, yet well within the shadows of the trees, and continued in this way for nearly half a mile. Then he suddenly disappeared.

Ray stood and looked about in surprise. He had seen the man's figure pretty clearly defined against the dim light outside the wood one moment, and the next he had vanished as completely as if the earth had swallowed him up. With infinite patience and care, Ray crept by degrees up to the spot upon which the man had been standing, and peered about on all sides, but could neither see any trace of him, nor form any sort of idea as to which way he had gone.

There was a small clearing at the place, and on one side of it some rocky ledges towered up, their bases half hidden by thick scrub. After waiting a little while and listening intently, Ray crept up to these rocks and decided to ascend them, in the hope that he might get a view which might give him some clue.

Arrived near the top, what was his surprise to hear distinctly the sound of voices below upon the other side. Peering over, he found himself looking down upon another clearing—a space quite shut in, not so much by trees as by almost perpendicular rocks, more or less covered by bushes. At the bottom was a light.

Creeping amongst some bushes, he wriggled himself forward until he was able to get a partial view of the clearing. There, through intervening foliage, he could make out several dusky figures seated round a fire. They looked like natives from some of the adjacent islands; and there, amongst them, was the Dago they had rescued from the monster of the pool!

How he had got to them seemed a mystery; but Ray guessed that there might be a secret way to this hidden retreat—perhaps through a cave or passage in the rock, the entrance to which might be concealed by bushes or creepers.

He decided to return to the camp and make sure that all was right there, and, in particular, see that a better watch was kept during the rest of the night. These natives might or might not be plotting mischief; in any case it would be best to be prepared; and as to the Dago—well, he would leave the doctor to deal with him in the morning.

So Ray set off on his return to the camp, and as he was nearing it he came suddenly upon Shorter.

"I—I—beg your pardon, sir," said the man somewhat confusedly. "I—I—had no idea you were about."

"Whom were you looking for, Shorter?" Ray asked. "And who is supposed to be on watch just now?"

"I am, sir, and I were just takin' a look round to see as everything were all right, when I heered some one a comin' along, an' I came to see who it could be."

"Humph! Well now, where's that Dago chap we brought into camp? Have you see anything of him?"

"Nothing, sir. I s'pose he's in his tent yonder."

Ray thought the man had started on his mentioning the stranger. He had intended going to the tent and proving to Shorter that he was not there; but an idea came into his mind that he would conceal, for the present, the knowledge he had just gained.

He therefore said nothing more, but bidding Shorter keep a good look-out, he went to his own tent and ostensibly turned in. As a matter of fact, however, he remained awake and kept a sharp look-out himself during the remainder of the night.

In the morning he found that the doctor was very unwell. His ankle had swollen badly, and looked so angry and inflamed that he reluctantly determined to give up, for the time, all idea of further exploration, and return to the ship, "where," he said, "I shall be within reach of the medicine chest."

Ray found that the Dago was missing, and he told the doctor what had occurred during the night.

"Ah! I'm not surprised," was the answer. "I fancied his tale was somewhat doubtful. He looked too fat and well-fed for a man who had been living alone and starving upon a diet of berries and shell-fish. Very likely he is in league with some natives from other islands, and perhaps has come over with a party. If we were going to stay here a day or two to explore further, it might be advisable to take some precautions against a possible surprise; but as we're returning to the ship, we can afford to say 'let him go and good riddance go with him.' "

With that Dr. Strongfold dismissed the subject from his mind, and gave the necessary orders for striking the tents and returning to the yacht.

Captain Warren had not expected to see the party again so soon, and was genuinely sorry at the doctor's mishap; but he showed only a languid interest in the account the explorers gave him of their adventures with the great lizard. When, however Ray told him about the Dago, and his midnight tramp through the forest, the old mariner's face puckered up.

"And Shorter was in it!" he mused. "This stranger fellow sneaks out of the camp and nobody knows anything about it—not even the man on watch—and that was Shorter! And the fellow had friends in the vicinity, too! I don't like the look of it, Mr. Ray, I don't like it."

The worthy captain shook his head dubiously as he went on deck, leaving Ray to tend the doctor in the cabin.

That evening Captain Warren sought Ray out, and after making sure that no one could overhear their conversation, asked him to aid him in keeping a sharp watch through the night.

"I've told you I'm uneasy in my mind, Mr. Ray," he said, "and during your absence from the ship I've been on the look-out myself nearly the whole time. I'm a'most done up. I'm responsible for the ship to your father, and somehow I felt mistrustful before; but your tale of that Dago chap, and the people you saw him steal out to meet, has made me more uneasy than ever. I don't like to say anything to the doctor—'specially now he's on the sick list—but you and I and Tom Waring must see to it that we keep up a good sharp look-out, between us, day and night!"

Ray was only too glad to help in the way suggested, and said so; and thus it came about that when the skipper turned in, Ray, who was supposed to have done the same, crept softly on deck instead, and ensconced himself in a corner under the awning, without the man on watch being aware of his presence.

The half-moon peeped out now and again between the drifting clouds, and Ray gazed dreamily across the water at the distant shores of the mysterious island. He began to feel a conviction that there was a great deal more to be discovered concerning the place than any one seemed to have an idea of. No doubt, for a long time—perhaps for hundreds of years—the country inland had been shut off from the rest of the world by the impassable swamps, with their rank growth of sea-weed and other tangled vegetation, which had baffled all the efforts of travellers to penetrate into the interior.

Now—comparatively speaking, quite recently—a waterway seemed to have opened which promised to make the task of future explorers less difficult—and who could say what those explorers might find there? Vague legends and stories came to his mind of lost races, and hidden cities. From them his thoughts passed to the captain's fears and misgivings, and his dark hints at acts of piracy which were said to have been committed in those seas, when whole ships, with their crews and passengers and cargoes, had disappeared without leaving behind a trace of the fate which had befallen them.

Suddenly, he started, and rubbed his eyes. The moon was behind some thick clouds, and the view around had become dim and obscured, yet surely there was something moving yonder! What was that large, black shadow, creeping stealthily out of the entrance to the inland waterway, and moving towards the yacht?

Again Ray rubbed his eyes, and then once more looked forth. The dark shadow was coming nearer. Something was certainly approaching the yacht in a stealthy, suspicious manner!

What did it mean? And the watch? Why had he made no sign of having seen it? Was he asleep or was he? Ray shrank from filling in the only possible alternative. He could not bring himself to believe in such vile treachery as the mere suspicion implied.

And while he turned these thoughts and speculations over in his mind, the mysterious black mass crept silently nearer and nearer to the yacht.

RAY'S mind was very quickly made up. There might be nothing hostile intended; but he was not going to give a chance to a possible enemy to catch them napping.

As silently as he had crept on deck, he now stole back again, and quietly woke Captain Warren and told him the position.

The skipper had everything ready for an emergency, and in a few minutes had made his arrangements without even the man on deck becoming aware that any one was awake on board but himself.

Then, mounting softly to the deck, Warren and Ray looked out from under the awning. The moon was still obscured, but there was no longer room for doubt.

A curious sort of craft was creeping up to the yacht—a great, black, galley-shaped affair, in design unlike anything the experienced skipper had ever set eyes on out of a museum. In some respects it resembled a large barge, but in others it might have been likened to the pictures one sees of the ancient ships of Greece or Rome, propelled by two or three banks of rowers.

Long sweeps sunk, without sound, into the water, and rose dripping, but noiseless, with methodical swing; but so ghostlike was the whole affair that Ray caught himself debating whether what they saw was really an actual vessel filled with living people, or a visionary phantom, tenanted by shades of the dead.

But the practical-minded skipper had no such doubts or speculations. He looked keenly at the advancing craft, and then his voice rang out clear, and sharp, and determined:—

"Boat ahoy, there! Who are you? What d'ye want?"

No answer came from the ghostly vessel, which came on as steadily and noiselessly as before.

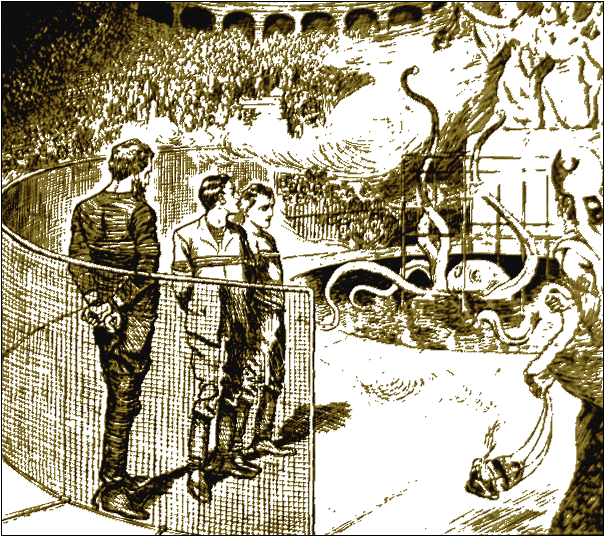

At the moment the captain's hail was heard the man who was supposed to be watching, but who was either asleep or pretending to be, had been roughly seized by a couple of men, who had stolen up behind him and promptly bound him there and then. It was Ridd Shorter!

He was roughly seized by a couple of men.

"Take him below and put him in irons!" said the captain, sternly. "I will deal with him to-morrow!"

And the fellow was unceremoniously bundled below.

"Boat ahoy!" sang out the captain's voice again. "No nonsense, you lubbers! Stop, or I will fire upon you!"

Still no answer; but the slow, heavy strokes of the long black sweeps were perceptibly quickened.

Captain Warren hesitated no longer. He put a whistle to his mouth and blew a quick, shrill blast.

Instantly a small but very business-like cannon made its appearance through what had appeared to be only an ordinary port- window, and the next moment there was a booming report, and a shot whizzed over the deck of the stranger.

Still she came on. Then there was heard another whistle, which was followed by another shot; and this time it did not fly overhead, but went crashing through the side of the strange craft, landing, apparently amongst those who were handling the sweeps. For a minute or two, they fell into evident confusion.

But at the same time the hitherto silent vessel became alive with men. There were shouts in an unknown language; there was much rattling of arms and clanking of steel, and then a flight of arrows fell, some with a clatter upon the deck of the yacht, some against her sides, or passed overhead into the sea beyond.

"What in thunder does this mean?" exclaimed the captain, at this most unlooked for demonstration. "Who are these people who've come to fight us with bows and arrows?"

"What an extraordinary affair!" said Ray. "See, they have breastplates and spears, and such-like arms; but no guns or pistols, it seems."

However, just then, as if in answer to what he had said, and to show that he was mistaken, there came a few straggling shots from firearms; but the bullets flew wide, and no harm was done.

"This is getting serious," Warren now declared. "If we don't stop 'em they'll be alongside directly, and if they board us we shall have a job to throw 'em off, for there's a big swarm of the varmints."

He blew three sharp blasts upon his whistle, and in a moment the deck of the yacht was full of men. It seemed like a conjuring trick; and it was wonderful where they sprang from. They crowded along the bulwark, and a moment later poured a volley from their rifles into the crowded deck of the stranger.

At the same time the cannon boomed out again, and above the general din could be heard the grinding rattle of a Maxim gun. Then Warren sounded the cease fire, for it was clear that the fight was over. The stranger's crew saw that they had caught a tartar in this innocent-looking yacht, and were now only anxious to get away as quickly as possible.

Warren would have liked to follow them, if only to find out who they were and what it all meant; but he had not steam up, and in any case to have captured the vessel it would probably have been necessary to engage in a terrible fight. So he reluctantly decided to let his unknown enemies go, and content himself with wondering and puzzling about the problem of their strange proceedings as best he could.

Just then Ray, who was alongside him, engaged in watching the retreating foe, caught sight of a dark form in the water, evidently swimming towards the yacht. Others saw it too, and some were about to fire at it, but he stopped them.

"Let the poor fellow alone," he cried, "He is but one, and cannot hurt us!"

"That's so," Warren assented. "Besides, if we get the beggar aboard he might tell us what the deuce this little excursion of his people may happen to mean!"

But those on the strange craft also saw the swimmer, and, no doubt, looking on him as a deserter, began shooting at him. Arrows fell near him, and one must have struck him, for he suddenly threw up his arms as if in pain. Then his voice was heard calling for help.

"Help, Britishers, help!" he cried. "I am one of you! I was a prisoner over there! Save me! Save your own countryman!"

"He is a Britisher and a prisoner," cried Ray, "we must save him!" And ere any one could say a word or interfere to prevent him, he had plunged overboard, and was swimming to the assistance of the stranger, regardless of the arrows, now mingled with a few bullets, which were falling around him.