RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Forain rose to his feet. "Yes, mademoiselle, I have

challenged the man who killed your brother."

IT was doubtless a strange coincidence that the two friends, the Frenchman and the Englishman, should have argued about that particular subject on that particular morning. The coincidence may perhaps appear less incredible to a philosophic mind, if I add that they had argued about that subject every morning through the whole month of the walking tour that they took in the country south of Fontainebleau. Indeed, it was this repetition and variety of aspect that gave the more logical and patient mind of the Frenchman the occasion of his final criticism.

"My friend," he said, "you have told me many times that you can make no sense of the French duel. Permit me the observation that I can make no sense of the English criticism of the French duel. When we discussed it yesterday, for instance, you twitted me with the affair of old Le Mouton with that Jew journalist who calls himself Vallon. Because the poor old Senator got off with a scratch on the wrist, you called it a farce."

"And you can't deny it was a farce," replied the other stolidly.

"But now," proceeded his friend, "because we happen to pass the Château d'Orage, you dig up the corpse of the old count who was killed there, God knows when, by a vagabond Austrian soldier of fortune, and tell me with a burst of British righteousness that it was a hideous tragedy."

"Well, and you can't deny it was a tragedy," repeated the Englishman. "They say the poor young countess couldn't live there in the shadow of it, and has sold the château and gone to Paris."

"Paris has its religious consolations," said the Frenchman, smiling somewhat austerely. "But I think you are unreasonable. A thing cannot be bad because it is too dangerous and too safe. If the duel is bloodless you call our poor French swordsman a fool. If it ends in bloodshed, what do you call him?"

"I call him a bloody fool," replied the Englishman.

The two national figures might have served to show how real is nationality, and how independent it is of race; or at least of the physical types commonly associated with race. For Paul Forain was tall, thin and fair, but French to the finger-tips, to the point of his imperial or the points of his long, narrow shoes, and in nothing more French than in a certain seriousness of curiosity that lifted his brow in a permanent furrow; you could see him thinking. And Harry Monk was short, sturdy and dark, and yet exuberantly English—English in his grey tweeds and in his short brown moustache; and in nothing so English as in a complete absence of curiosity, so far as was consistent with courtesy. He carried the humour, and especially the good humour, of the English social compromise with him like a costume; just as one might fancy his grey tweeds carried the grey English weather with him everywhere through those sunny lands. They were both young, and both professors at a famous French college—the one of jurisprudence, the other of English; but the former, Forain, had specialized so much in certain aspects of criminal law that he was often consulted on particular criminal problems. It was certain views of his about murder and manslaughter that had Jed to the recurrent disagreement about the duel. They commonly took their holidays together, and had just breakfasted at the inn of the Seven Stars half a mile along the road o behind them.

Dawn had broken over the opposite side of the valley and shone full on the side on which their road ran. The ground fell towards the river in a series of tablelands like a terraced garden, and on the one just above them were the neglected grounds and sombre façade of the old château, flanked to left and right by an equally sombre façade of firs and pines, deployed interminably like the lost lances of any army long fallen into dust. The first shafts of the sun, still tinged with red, gleamed on a row of glass frames for cucumbers or some such vegetables, suggesting that the place was at least lately inhabited, and warmed the dark diamonded casements of the house itself, here and there turning a diamond into a ruby. But the garden was overgrown with clumps of wood almost as accidental as giant mosses, and somewhere in its melancholy maze, they knew, the sinister Colonel Tarnow, an Austrian soldier, since not unsuspected of being an Austrian spy, had thrust his blade into the throat of Maurice d'Orage, the last lord of that place. The path descended, and the view over the hedge was soon shut out by a great garden wall so loaded with ivies and ancient vines and creepers that it looked itself more like a hedge than a wall.

"I know you've been out yourself, and I know you're far from being a brute yourself," conceded Monk, continuing the conversation. "For my own part, however much I hated a man, I don't fancy I should ever want to kill him."

"I don't know that I did want to kill him," answered the other. "It would be truer to say I wanted him to kill me. You see, I wanted him to be able to kill me. That is what is not understood. To show how much I would stake on my side of the quarrel—hallo! What on earth is this?"

On the ivied wall above had appeared a figure, almost black against the morning sky, so that they could see nothing of its face, but only its one frenzied gesture. The next moment it had leapt from the wall and stood in their path, with hands spread out as if for succour.

"Are you doctors, either of you?" cried the unknown. "Anyhow, you must come and help—a man's been killed."

They could see now that the figure was that of a slim young man whose dark hair and dark clothes showed the abrupt disorder only seen in what is commonly orderly. One curl of his burnished black hair had been plucked across his eye by an intercepting branch, and he wore pale yellow gloves, one of which was burst across the knuckles.

"A man killed?" repeated Monk. "How was he killed?"

The yellow-gloved hand made a despairing movement.

"Oh, the wretched old tale!" he cried. "Too much wine, too many words, and the end next morning. But God knows we never meant it to go so far as this!"

With one of the lightning movements that lay hidden behind his rather dry dignity, Forain had already scaled the low wall and was standing on it, and his English friend followed with equal activity and more unconcern. As soon as they stood there they saw on the lawn below the sight that explained everything, and made so wild and yet apt a commentary on their own controversy.

The group on the lawn included three other men in black frockcoats and top hats, excluding the messenger of misfortune, whose own silk hat lay rolled at random by the wall over which he had leapt. He seemed to have leapt it, by the way, with an impetuosity that spoke of a swift reaction of horror or repentance, for Forain noticed, only a yard or two along the garden wall, a garden door, which, though doubtless disused, rustily barred and blotched with lichen, would have been the natural exit of a more normal moment. But the eye was very reasonably riveted on the two figures, clad only in white shirts and trousers, round whom the rest revolved, and who must have crossed swords a moment before. One of these stood with the rapier still poised in his hand, a mere streak of white, which a keen eye might have seen to end in a spot of red. The other white-shirted figure lay like a white rag on the green turf, and a sword of the same pattern, a somewhat antiquated one, lay gleaming in the grass where it had fallen from his hand. One of his black-coated seconds was bending over him, and as the strangers approached lifted a livid face, a face with spectacles and a black triangular beard.

"It's too late," he said. "He's gone."

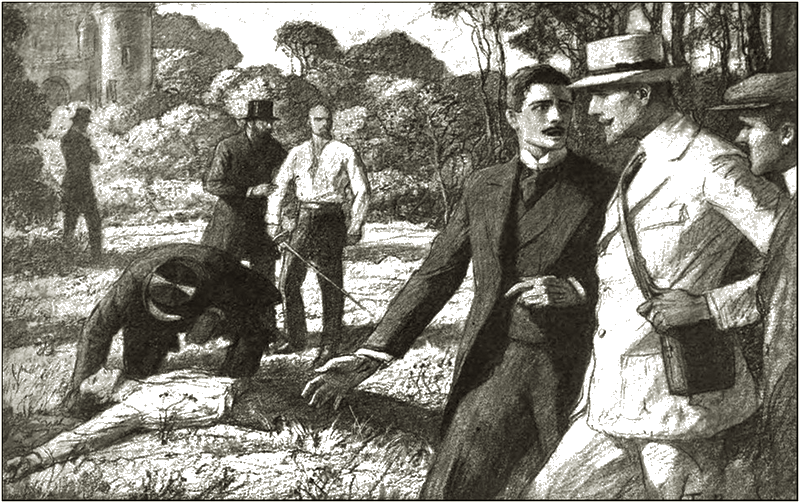

The other white-shirted figure lay like a white rag

on the green turf. One of his black-coated seconds was

bending over him. "It's too late," he said. "He's gone."

The man still holding the sword cast it down with a wordless sound more shocking than a curse. He was a tall, elegant man, with an air of fashion even in his duelling undress; his face, with a rather fine aquiline profile, looked whiter against red hair and a red pointed beard. The man beside him put a hand upon his shoulder and seemed to push him a little, perhaps urging him to fly. This witness, in the French phrase, was a tall, portly man with a long black beard cut as if in the square pattern of his long black frockcoat, and having, somewhat incongruously, a monocle screwed into one eye. The last of the group, the second of the slayer's formal backers, stood motionless and somewhat apart from the rest—a big man, much younger than his comrades, and with a classical face like a statue's and almost as impassive as a statue's. By a movement common to the whole tragic company, he had removed his top hat at the final announcement, as if at a funeral, and the effect gave to English eyes a slight shock; for the young man's hair was cropped so close and so colourless that he might almost have been bald. The fashion was common enough in France, yet it seemed incongruous to the man's youth and good looks. It was as if Apollo were shaved as an Eastern hermit.

"Gentlemen," said Forain at last, "since you have brought me into this terrible business, I must be plain. I am in no position to be pharisaic. I have all but killed a man myself, and I know that the riposte can be almost past control. I am not," he added, with a faint touch of acidity, "a humanitarian, who would have three men butchered with the axe of the guillotine because one has fallen by the sword. I am not an official, but I have some official influence; and I have, if I may say so, a reputation to lose. You must at least convince me that this affair was clean and inevitable like my own, otherwise I must go back to my friend the innkeeper of the Seven Stars, who will put me in communication with another friend of mine, the chief of police."

And without further apology, he walked across the lawn and looked down at the fallen figure, a figure peculiarly pathetic because plainly younger than any of the survivors, even his second who had run for help. There was no hair on the pale face; the hair on the head was very fair and brushed in a way which Monk, with a new shock of sympathy, recognized as English. There was no doubt of the death; a brief examination showed that the sword had been sent straight through the heart.

The big man with the big black beard broke the silence in reply:

"I will thank you, sir, for your candour, since I am, in some melancholy sense, your host on this occasion. I am Baron Bruno, owner of this house and grounds, and it was here at my table that the mortal insult was given. I owe it to my unfortunate friend Le Caron"—and he made a gesture of introduction towards the red-bearded swordsman, "to say it was a mortal insult, and followed by a direct challenge. It was a charge of cheating at cards, and it was clinched by one of cowardice. I mean no harshness to the dead, but something is due to the living."

Monk turned to the dead man's seconds. "Do you support this?" he demanded.

"I suppose it's all right," said the young man with the yellow gloves. "There were faults on both sides."

Then he added abruptly: "My name is Waldo Lorraine, and I'm ashamed to say I am the fool who brought my poor friend here to play. He was an Englishman, Hubert Crane, whom I met in Paris, and meant, heaven knows, only to give a good time! And the only service I've done him is to be his second in this bloody ending. Dr. Vandam here, being also a stranger in the house, kindly acted as my colleague. The duel was regular enough, I must fairly say, but the quarrel was—" He paused, a shadow of shame darkening his dark face. "I have to confess I was no judge of it, and have no memory but a sort of nightmare. In plain words, I had drunk too much to know or care."

Dr. Vandam, the pale man in the spectacles, shook his head mournfully, still staring at the corpse.

"I can't help you," he said. "I was at the Seven Stars, and only came in time to arrange for the fight."

"My own fellow-witness, M. Valence," observed the baron, indicating the man with the cropped hair, "will ratify my version of the dispute."

"Had he any papers?" asked Forain after a pause. "May I examine the body?"

There was no opposition, and, after searching the dead man and his waistcoat and coat that lay on the lawn, the investigator at last found a single letter, short but confirmatory, so far as it went, of the story told him. It was signed "Abraham Crane," and was plainly from the dead man's father in Huddersfield; indeed, Monk was able to recognize the name as that of a noted manufacturing magnate in the north. It merely concerned business on which the young man had been sent to Paris, apparently to confirm some contract with the Paris branch of the firm of Miller, Moss & Hartman; but the rather sharp adjuration to avoid the vanities of the French capital suggested that perhaps the father had some hint of the dissipations that had brought the son to his death. One thing only in this very commonplace letter puzzled the inquirer not a little. It ended by saying that the writer might himself be coming to France to hear the upshot of the Miller, Moss & Hartman affair, and that if so he would put up at the Seven Stars and call for his son at the Château d'Orage. It seemed odd that the son should have given the address of the very place where he was living the riotous life his father so strongly condemned. The only other object in the pockets besides the common necessaries was an old locket enclosing the faded portrait of a dark lady.

Forain stood frowning a moment, the paper twisted in his fingers; then he said abruptly: "May I go up to your house, Monsieur le Baron?"

The baron bowed silently; they left the dead man's seconds to mount guard over his body, and the rest mounted slowly up the slope. They went the slower for two reasons—first, because the steep and straggling path was made more irregular by straggling roots of pine like the tails of dying dragons, and slippery with green slime that might have been their own green and unnatural gore; and second, because Forain stopped every now and then to take what seemed needless note of certain details of the general decay. Either the baron had not long been in possession of the place, or he cared very little for appearances.

What had once been a garden was eaten by giant weeds, and when they passed the cucumber frames on the slope Forain saw they were empty and the glass of one of them had a careless crack, like a star in the ice. Forain stood staring at the hole for nearly a minute.

Entering the house by the long french windows, they came first on a round outer room with a round card-table. It might by the shape have been a turret-room, but seemed somehow as light and sunny as a summer-house, being white and gold in the ornate eighteenth-century style. But it was as faded as it was florid, and the white had grown yellow and the gold brown. At the moment this decay was but the background of the silent yet speaking drama of a more recent disorder. Cards were scattered across the floor and table, as if flung or struck flying from a hand that held them; champagne bottles stood or lay at random everywhere, half of them broken, nearly all of them empty; a chair was overturned. It was easy to believe all that Lorraine had said of the orgy that now seemed to him a nightmare.

"Not an edifying scene," said the baron, with a sigh, "and yet I suppose it has a moral."

"It may appear singular," replied Forain, "but in my own moral problem it is even reassuring. Given the death, I am even glad of the drink."

As he spoke he stooped swiftly and picked up a handful of cards from the carpet.

"The five of spades," he said to Monk musingly in English, "the five of swords, as the old Spaniards would say, I suppose. You know 'spade' is 'espada,' a sword? The four of swords—spades, I mean. The three of spades. The—have you got a telephone here?"

"Yes—in another room, round by the other door of the house," answered the baron, rather taken aback.

"I'll use it, if I may," said Forain, and stepped swiftly out of the card-room. He strode across a larger and darker salon within, which for some reason had remained in a sterner and more antiquated style of decoration. There were antlers above him; a glimmer of armour showed on the gloom of oak and tapestry, and he saw one thing that arrested his eye as he strode towards the farther door. A trophy of two swords crossed was on one side of the fireplace, and on the corresponding place opposite the empty hooks of another. He understood why the two rapiers had seemed to be antiquated. Under the ominous empty hooks stood an ebony cabinet carved with cherubs as grotesque as goblins.

Forain felt as if the black cherubim were peering at him with a curiosity quite unangelic. He gazed a moment at the drawers of the cabinet, and passed on.

He shut the door behind him, and they heard another door close in a more distant part of the building, away towards the road that ran on the remoter side of the house. There was a silence; they could hear neither the bell nor the talk at the telephone.

Baron Bruno had dropped the glass from his eye, and was plucking a little nervously at his long dark beard.

"I suppose, sir," he said, addressing Monk, "we can count on your friend's feeling of honour?"

"I am certain of his honour," said the Englishman, with the faintest accent on the possessive pronoun.

The surviving duellist, Le Caron, spoke for the first time, and roughly.

"Let the man telephone," he said. "No French jury would call this miserable thing murder. It was almost an accident."

"One to be avoided, I think," said Monk coldly.

Forain had reappeared, and his brow was cleared of its wrinkle of reflection. "Baron," he said, "I have resolved my little problem. I will treat this tragedy as a private misfortune on one condition—that you all meet me and give me an account that satisfies me within this week, and in Paris. Say outside the Café Roncesvaux on Thursday night. Does that suit you? Is that understood? Very well, let us return to the garden."

When they went out again through the french windows the sun was already high in heaven, and every detail of the slope and lawn below glittered with a new clarity. As they turned the corner of a clump of trees and came out above the duelling-ground, Forain stopped dead and put on the Baron's arm a hand that caught like a hook.

"My God!" he said. "This will never do. You must get away at once."

"What?" cried the other.

"It's been quick work," said the investigator. "The father's here already."

They followed his glance down to the garden by the wall, and the first thing they saw was that the rusty old garden door was standing open, letting in the white light of the road. Then they realized that a few yards within it was a tall, lean, grey-bearded man, clad completely in black and looking like some Puritanic minister. He was standing on the turf and looking down at the dead. A girl in grey, with a black hat, was kneeling by the body, and the two seconds, as by an instinct of decency, had withdrawn to some distance and stood gazing gloomily at the ground. In the clear sunlight the whole group looked like a lighted scene on a green stage.

"Go back at once—all three of you," said Forain almost fiercely. "Get away by the other door. You must not meet him, at least."

The Baron, after an instant's hesitation, seemed to assent, and Le Caron had already turned away. The slayer and his two seconds moved towards the house and vanished into it once more, the tall young man with the shaven head going last with a leisure that made even his long legs look cynical. He was the only one of them who scarcely seemed affected at all.

"Mr. Crane, I think," said Forain to the bereaved father. "I fear you know all that we can tell you."

The grey-bearded man nodded; there was a certain frost-bitten fierceness about his face and something wild in the eye contrasting with the control in the features, something that seemed natural enough at such a time, but which they found afterwards to be more normal to him even in ordinary times.

"Sir," he said, "I have seen the end of cards and wine and the Lord's judgments for everything I feared." Then he added, with an incongruous simplicity somehow rather tragic than comic: "And fencing, sir. I was always against all that French fad of getting prizes for fencing. Football is bad enough, with betting and every sort of brutality, but it doesn't lead to this. You are English, I think?" he said abruptly to Monk. "Have you anything to say of this abominable murder?"

"I say it is an abominable murder," said Monk firmly. "I was saying so to my friend hardly half an hour ago."

"Ah, and you?" cried the old man, looking suspiciously at Forain. "Were you defending duels, perhaps?"

"Sir," replied Forain gently, "it is no time for defending anything. If your son had fallen from a horse, I would not defend horses; you should say your worst of them. If he had been drowned in a boat, I would join you in wishing every boat at the bottom of the sea."

The girl was looking at Forain with an innocent intensity of gaze which was curious and painful, but the father turned impatiently away, saying to Monk: "As you are English at least, I should like to consult you." And he drew the Englishman aside.

But the daughter still looked across at Forain without speech or motion, and he looked back at her with a rather indescribable interest. She was fair, like her brother, with yellow hair and a white face, but her features were irregular with that fairy luck that falls right once in fifty times, and then is more beautiful than beauty. Her eyes seemed as colourless as water, and yet as bright as diamonds, and when he met them the Frenchman realized, with a mounting and unmanageable emotion, that he was facing something far more positive than the laxity of the son or the limitations of the father.

"May I ask you, sir," she said steadily, "who were those three men with you just now? Were they the men who murdered him?"

"Mademoiselle," he said, feeling somehow that all disguises had dropped, "you use a harsh, word, and heaven knows it is natural. But I must not stand before you on false pretences. I myself have held such a weapon and nearly done such a murder."

"I don't think you look like a murderer," she said calmly. "But they did. That man with the red beard, he was like a wolf—a well-dressed wolf, which is the worst part of it. And that big, pompous man—what could he be but horrible, with his big black beard and a glass in one eye?"

"Surely," said Forain respectfully, "it is not wicked to be well dressed, and a man might be more sinned against than sinning and still have a beard and an eyeglass."

"Not all that big beard and that one little eyeglass," she replied positively. "Oh, I only saw them in the distance, but I know quite well I'm right."

"I know you must think any duellist is a criminal and ought to be punished," said Forain rather huskily. "Only, having been one myself—"

"I don't," she said. "I think those duellists ought to be punished. And, just to prove what I mean and don't mean"—and her pale face was changed with a puzzling and yet dazzling smile—"I want you to punish them."

There was a strange silence, and she added quietly:

"You have seen something yourself. You have some guess, I am sure, about how they came to fight, and what was really behind it all. You know there is really something wrong, much more wrong than the quarrel about cards."

He bowed to her, and seemed to yield like a man rebuked by an old friend.

"Mademoiselle," he said, "I am honoured by your confidence. And your commission."

He straightened himself equally abruptly, and turned to face the father, who had drawn near again in conversation with Monk.

"Mr. Crane," he said gravely, "I must ask you for the moment to trust me. This gentleman, as well as other countrymen of yours to whom I can refer you, will, I think, tell you that I can be trusted. I have already communicated with the authorities, and you may even regard me in a sense as their representative. I can answer for the fact that those responsible in this dreadful affair are under observation, and that justice can effect whatever may be found to be just. If you will honour me with an appointment in Paris after Tuesday next, I can tell you more of many things that you ought to know. Meanwhile, I will make any arrangements you desire touching the—formalities of respect for the dead."

The eye of old Crane was still choleric, but he bowed, and Forain and Monk, returning the salutation, retraced their way up the path to the château. As they did so the Frenchman paused again by the cucumber frame and pointed to the broken glass.

"That's the biggest hole in the story so far," he said; "it gapes at me like the mouth of hell."

"That!" exclaimed his friend. "That might have happened any time."

"It happened this morning," said Forain, "or else—anyhow, the broken bits are fresh; nothing has grown round them. And there is the mark of a heel on the soil inside. One of these men stepped straight on to the glass going down to the duelling ground. Why?"

"Oh, well," observed Monk, "that fellow Lorraine said he was blind drunk last night."

"But not this morning," replied Forain. "And though a man blind drunk, even in broad daylight, might conceivably put his foot into a big glass frame right in front of him, I doubt if he could take it out again so neatly. If he were as drunk as that, I think the mantrap would trip and throw him, and there would be more broken glass. This does not look to me like a man who was blind drunk. It is more like a man who was blind."

"Blind!" repeated Monk, with a quite irrational creeping of the flesh. "But none of these men are blind. Is there any other explanation?"

"Yes," replied Forain. "They did it in the dark. And that is the darkest part of the business."

ANYONE who had tracked the course of the two friends on the ensuing Thursday evening, when dusk had already kindled around them the many-coloured lights of Paris, might have imagined that they had no purpose but the visiting of a variety of cafés. Yet their course, though crooked and erratic, was designed according to the consistent strategy of the amateur detective. Forain went first to see the countess, the still surviving widow of the nobleman who fell fifteen years before, in a duel on the same spot. He went in a literal sense to see her, and not to call on her. For he contented himself with sitting outside the café opposite her house and playing with an apéritif until she came out to her carriage—a dark-browed lady, with a beauty rather fixed like a picture than still living like a flower: a portrait from a mummy-case. Then he merely glanced at the portrait in the old locket he had taken from the dead man's pocket, nodded almost approvingly, and made his way across the river to a less aristocratic and more purely commercial part of the town. Passing rapidly along a solid street of banks and public buildings, he reached a large hotel built on the same ponderous pattern, but having the usual litter of little tables on the pavement outside. They were intercepted with ornamental shrubs and covered with an awning striped with white and purple, and at a table at the extreme corner, against the last green afterglow of evening, he saw the black bulk of Baron Bruno sitting between his two friends. The awning that shaded them just cut off the upper part of his tall black hat, and Monk had the fancy that he resembled some black Babylonian caryatid supporting the whole building; perhaps there was something Assyrian about his large square beard. The Englishman felt a subconscious temptation to share his countrywoman's prejudice, but it was evident that Forain did not share it. For he sat down with the three men, and began to exhibit a very unexpected camaraderie and even conviviality. He ordered wine and pressed it upon them, passing afterwards into animated conversation, and it was not until about half an hour afterwards that our imaginary spectator, hovering on his trail, would have seen him start up with a slight return to stiffness, salute the company and resume his singular journey.

His zigzag course through the lighted city carried him first to a public telephone and then to a public office, which Monk was able to identify as the place where the dead body was awaiting medical examination. From this place he came out looking very grim, like one who has faced an ugly fact, but he said nothing and pursued his course to the police headquarters, where he was closeted for some time with the authorities. Then he crossed the river once more, walking swiftly and still in silence, and in a quiet corner of Paris struck the worn white gateway of a building that had once been an hotel in the ancient and aristocratic sense, and was now an hotel in a more commercial, but particularly quiet fashion. Passing through the porch and passages, he came out on a garden so secluded that the very sunset sky seemed a private awning of gold and green like the awning of purple and silver under which the sombre baron had sat. A few guests in evening dress were scattered at tables under the trees, but Forain went swiftly past them to one table near a flight of garden steps, at which he could see a girl in grey with golden hair. It was Margaret Crane; she looked up as he approached, but she only said, as if breathlessly: "Do you know any more about the murder?"

Before he could reply her father had appeared at the top of the steps, and Forain felt vaguely that while the girl's grey dress seemed to harmonize with everything, the rigid and rusty black of the old man's clothes remained like the protest of a Puritan in a garden of Cavaliers.

"The murder," he repeated in a loud and harsh voice, heard everywhere: "That's what we want to know about. This murder, sir!"

"Mr. Crane," said Forain, "I hope you know how I feel your position, but it is only fair to warn you that in these criminal matters one must speak carefully. If it comes to a trial, your case will be none the better if you have abused these men at random, even in private. And I am bound to say, not only that the duel as a duel seems to have been regular, but that the duellists seem to be men of marked regularity."

"What do you mean?" demanded the old man.

"I will be frank with you and own I have seen them since," said Forain. "Nay, I have passed a sort of festive evening with them—or what I meant to be a festive evening. But I am forced to say they are as little festive as your own conscience could desire. Indeed, they seem to have business habits very much like your own. Frankly, I tried to make them drink and to draw them into a game of cards, but the baron and his friends coldly declined, said they had appointments, and we parted after black coffee and a brief and rather curious conversation. "

"I hate them the more for that," said the girl.

"You are quick, Mademoiselle," observed Forain, with a growing admiration. "I also took the matter in that spirit, if only for experiment. I said bluntly to our baronial friend: 'So long as I thought you were a drinking and a dicing company, I took this for a drunken accident. But let me tell you it does not look well when elderly men, themselves sober, themselves indifferent to play, get a mere boy among them and play cards with him. You know what is thought of that; it is thought that the old man takes a hand—well, rather too like an old hand. And it is worse when he silences his opponent by fencing like an old hand also.'"

"And what did they say to that?" asked the girl.

"It is painful to me to repeat it," said Forain, "but it was quite as uncomfortable a surprise to me. Just as I seemed to have cornered them finally, that red-bearded man, Le Caron, whose sword made the mortal thrust, himself broke in like one abandoning disguise, with impatience and passion. 'I respect the dead,' he said, 'but you force me from any reticence. I can only tell you it was not we, the elder men, who dragged the boy into drink; it was he who dragged us. He arrived at the château half drunk already, and insisted on the baron ordering champagne from the Seven Stars down the road, for we were a temperate party and the cellar was not even stocked. It was he who insisted on play; it was he who taunted us with being afraid to play; it was he who at last added, quite wantonly and in wild falsehood, the intolerable taunt that we cheated at play.'"

"I will not believe it," said Crane, but his daughter remained silent, with her pale and penetrating face turned towards the amateur detective, who continued his report of the conversation.

"'Oh, I don't ask you to take my word,' Le Caron went on. 'Ask Lorraine himself, ask Dr. Vandam himself, who was sent to the inn for the wine, so that he was away when the row occurred. He stopped behind there to settle, and wasn't sorry, I think, to be out of it. He also, like myself, is glad to be bourgeois in these matters. Ask the innkeeper himself; he will tell you the wine was bought well on in the evening, after the young man arrived. Ask the people at the railway station; they will tell you when the young man arrived. You can easily test my story.'"

"I can see by your face," said the girl in a low voice, "that you have tested it. And you have found it true."

"You see the heart of things," said Forain.

"I cannot see the hearts of these men," she answered. "But I can see the hollows where their hearts should be."

"You still find them horrible," he said. "Who can blame you?"

"Horrible!" cried the old man. "Didn't they murder my son?"

"I speak only as an adviser," observed the Frenchman. "I know you cannot believe a duellist could be a respectable man. I only say that, as a fact, these seem to be respectable men. I have not only verified their tale, but traced back something of their past. They seem to have been concerned with commercial things, but solidly and on a considerable scale; I am in touch with the police dossiers, and should know of any other such scandals about them. Forgive me; I fear I do think that a duel is sometimes justifiable. I will not horrify you by saying that this one was justifiable; I only warn you that, in French opinion, they may be able to justify it."

"Yes," said the girl. "They grow more horrible as you speak of them. Oh! that is the really horrible man—the man who can always be justified. Honest men leave more holes gaping, like my poor brother, but the wicked are always in armour. Is there anything so blasphemous as the bad man's case when his case is complete, as the lawyers say; when the judge gravely sums up, and the jury agree and the police obey, and everything goes on oiled wheels? Is there anything so oily as the smell of that oil? It is then I feel I cannot wait for the Day of Judgment to crack their whited sepulchres."

"And it is then," said Forain quietly, "that I fight a duel."

The girl started a little. "Then?" she repeated.

"Then," repeated the Frenchman, lifting his head. "You, mademoiselle, have uttered the defence of the good duellist. You have proved the right of the private gentleman to draw a private sword. Yes, it is then that I do this criminal and bloody thing that so much horrifies you and your father. Yes, it is then that I become a murderer. When there is no crack in the whitewash and I cannot wait for the wrath of God. And permit me the reminder that you have not yet heard the end of my interview with the men who have left you in mourning."

Crane still stared in frosty suspicion, but the girl, as Forain suggested, had great intuitions. Her face and eyes kindled as she gazed.

"You don't mean—" she began, and then stopped.

Forain rose to his feet. "Yes," he said. "Being such a bloodthirsty character, I must no longer remain in company so respectable. Yes, mademoiselle, I have challenged the man who killed your brother."

"Challenged!" repeated the bristling Crane. "Challenged—more of this—of this butchery!" and he choked. But the girl had risen also and stretched out her hand like a queen.

"No, father," she said. "This gentleman is our friend, and he caught me out fairly. But I see now that there is more in French wit than we have understood; yes, and more in French duelling."

With a heightened colour and a lowered voice, Forain answered: "Mademoiselle, my inspiration is English." And, with a rather abrupt bow, he strode away, accompanied by Harry Monk, who regarded him with a contained amusement.

"I cannot affect to hope," said Monk airily, "that I myself constitute the English inspiration of your life."

"Nonsense," said the other rather testily, "let us get back to business. As I imagined your views on duelling were so similar to old Crane's that you could not consistently represent me, I've asked his unfortunate son's seconds to act as mine. I believe that young Lorraine will be of great use in helping us to probe this mystery. I have talked to him, and I am convinced of his great ability."

"And you have talked to me for years," said Monk, laughing, "and you are convinced of my great stupidity."

"Of your great sincerity," said Forain. "That is why I do not ask you to help me here."

MONK'S scruples, however, did not prevent his being present at the new encounter that had been so rapidly and even irregularly arranged. And his travels with his eccentric friend, which had already begun to remind him of the overturns and recurrences of a nightmare, brought him a few days later back to the old duelling ground of the Château d'Orage. The garden of Baron Bruno had apparently been selected for a second time as a sort of concession to the baron's party, but it was a rather grim privilege, and they evidently felt it as such. So little disposed were they, indeed, to linger about the place where they had once feasted and fought, that the baron's motor was waiting in the road without to take them back immediately to Paris.

Forain had always vaguely felt that the baron was very tenuously attached to his house and property, and in this case his party seemed to revisit it like ghosts. The prejudice of Margaret Crane would have said that a shadow of doom was visibly closing in on them. But it was more reasonable, and consonant with the more quiet and bourgeois character to which they seemed entitled, to suppose that they were naturally distressed at returning to the scene of their one reluctant deed of blood. Whatever the reason, the baron's brown face was heavy and sombre, and Le Caron, when he again found himself standing sword in hand on that fatal grass, was so white that his beard looked scarlet, like false hair or fiery paint. Monk almost fancied that the bright point of the poised rapier was faintly vibrant, as in a hand that shook.

The pine-shadowed park, with its careless and almost colourless decay, seemed a place where centuries might pass unnoticed. The white morning light served only to accentuate the grey details, and Monk caught himself fancying that it was truly the ashen vegetation of primeval aeons. This may have been an effect of his nerves, which were not unnaturally strained. After all, this was the third duel in those grounds, and two had ended in death; he could not but wonder if his friend was to be the last victim. Anyhow, it seemed to him that the preliminaries were intolerably lengthy. Le Caron had long and low-voiced consultations with the lowering baron; and even Forain's own seconds, Lorraine and the doctor, seemed more inclined to wait and whisper than to come to the mortal business. And all this was the more strange because the fight, when it did come at last, seemed to be over in a flash, like a conjuring trick.

The swords had barely touched twice or thrice when Le Caron found himself swordless. His weapon had twitched itself like a live thing out of his hand, and went spinning and sparkling over the garden wall; they could hear the steel tinkle on the stones of the road. Forain had disarmed him with a turn of the wrist.

Forain straightened himself and made a salute with his sword.

"Gentlemen," he said, "I am quite satisfied, if you are. After all, it was a slight cause of quarrel, and the honour of both parties is, so far, secure. Also, I understand, you gentlemen are anxious to get back to town."

Monk had long felt that his friend was more and more disposed to let the opposite group off lightly; he had long been speaking of them soberly as sober merchants. But whether or no it was the anti-climax of safety, he had a sense that the figures opposite had shrunk, and were more commonplace and ugly. The eagle nose of Le Caron looked more like a common hook; his fine clothes seemed to sit more uneasily on him, as on a hastily dressed doll; and even the solid and solemn baron somehow looked more like a large dummy outside a tailor's shop. But the strangest thing of all was that the baron's other colleague, Valence, of the shaven head, was standing astraddle in the background, wearing a broad though a bitter grin.

As the baron and the defeated duellist made their way rather sullenly through the garden door to the car beyond, Forain went up to this last member of the strange group, and (much to Monk's surprise) talked quickly and quietly for several minutes. It was only when Bruno's great voice was heard calling his name from without that this last figure also turned and left the garden.

"Exeunt brigands!" said Forain, with a cheerful change in his voice, "and now the four detectives will go up and examine the brigands' den."

And he turned and began once again to mount the slope to the château, the rest following in single file. Monk, who was just behind him, remarked abruptly when they were halfway up the ascent:

"So you didn't kill him, after all?"

"I didn't want to kill him," replied his French friend.

"What did you want?"

"I wanted to see whether he could fence," said Forain. "He can't."

Monk eyed in a puzzled manner the tall, straight, grey-clad back of the figure mounting ahead of him, but was silent till Forain spoke again.

"You remember," continued that gentleman, "that old Crane said his unfortunate son had actually got prizes for fencing. But that carroty-whiskered Mr. Le Caron hardly knows how to hold a foil. Of course, it's very natural j after all, he is but a quiet business man, as I told you, and deals more in gold than steel."

"But, my good man," cried Monk, addressing the back in exasperation, "what the devil does it all mean? Why was Crane killed in the duel?"

"There never was any duel," said Forain, without turning round.

Dr. Vandam behind uttered an abrupt sound as of astonishment, or perhaps enlightenment; but, though it was followed by many questions, Forain said no more till they stood in the long inner room of the château, with the weapons on the wall and the ebony cabinet, on which the black cherubs looked blacker than ever. Forain felt more darkly a certain contradiction between their colour and shape, that was like a blasphemy. Black cherubs were like the Black Mass—they were symbols of some idea that hell is an inverted copy of heaven, like a landscape hanging downwards in a lake.

He shook off his momentary dreams and stooped over the drawers of the cabinet, and when he spoke again it was lightly enough.

"You know the château, Monsieur Lorraine," he said, "and I expect you know the cabinet, and even the drawer. I see it's been opened lately." The drawer, indeed, was not completely closed, and, giving it a sudden jerk, he pulled it completely out of the cabinet. Without further words he bore it, with its contents, back into the card-room and put it on the round table; and at his invitation his three colleagues or co-detectives drew up their chairs and sat round it. The drawer seemed to contain the contents of an old curiosity shop, such as Balzac loved to describe—a tumbled heap of brown coins, dim jewels and trinkets, of which tales, true and false, are told.

"Well, what about it?" asked Monk. "Do you want to get something out of it?"

"Not exactly," replied the investigator. "I rather fancy I want to put something into it."

He pulled from his pocket the locket with the dark portrait, and poised it thoughtfully in his hand.

"We have now to ask ourselves," went on the detective to his colleagues, "why young Crane was carrying this, which is a portrait of the countess?"

"He went about Paris a good deal," said Dr. Vandam rather grimly.

"If she knew him well," proceeded Forain, "it seems strange she has taken no notice of his sad end."

"Perhaps she knew him a little too well," cried Lorraine, with a little laugh. "Or, perhaps, though it's an ugly thing to say, she was glad to be rid of him. There were uglier stories when her husband, the old count—"

"You know the château, Monsieur Lorraine?" repeated Forain, looking at him steadily and even sternly. "I think that's where the locket came from." And he tossed it on to the many-coloured heap in the drawer.

Lorraine's eyes were literally like black diamonds as he gazed fascinated at the heap; he seemed really too excited to reply. Forain continued his exposition.

"Poor Crane, I fancy, must have found it here. Or else somebody found it here and gave it to him. Or else somebody—by the way, surely that's a real Renascence chain there—Italian and fifteenth century, unless I'm wrong. There are valuable things here, Monsieur Lorraine, and I believe you're a judge of them."

"I know a little about the Renaissance," answered Lorraine, and the pale Dr. Vandam flashed a queer look at him through his spectacles.

"There was a ring, too, I suspect," said Forain. "I have put back the locket. Would you, Monsieur Lorraine, kindly put back the ring?"

Lorraine rose, the smile still on his lips; he put two fingers in his waistcoat pocket and drew out a small circlet of wrought gold with a green stone.

The next moment Forain's arm shot across the table trying to catch his wrist; but his motion, though swift as his sword-thrust, was yet too late. Young Mr. Waldo Lorraine stood with the smile on his lips and the Renaissance ring on his finger while one could count five. Then his feet slipped on the smooth floor and he fell dead across the table, with his black ringlets among the rich refuse of the drawer. Almost simultaneously with the shock of his fall, Dr. Vandam had taken one bound, burst out of the french window's and disappeared down the garden like a cat.

"Don't move," said Forain with a steely steadiness. "The police are on the watch. I laid them on the other day in Paris when I saw poor Crane's body."

"But surely," cried his bewildered friend, "it was not only then that you saw the wound on his body."

"I mean the wound on his finger," said Forain.

He stood a minute or two in silence, looking down at the fallen figure across the table with pity and something almost like admiration.

"Strange," he said at last, "that he should die just here, with his head in all that dustbin of curiosities that he was born among and had such a taste for. You saw he was a Jew, of course, but, my God, what a genius! Like your young Disraeli—and he might have succeeded too and filled the world with his fame. Just a mistake or two, breaking a cucumber frame in the dark, and he lies dead in all that dead bric-à-brac, as if in the pawnshop where he was born."

"Strange that he should die just here, with his head in all that dust-

bin of curiosities that he was born among and had such a taste for."

The next appointment Forain made with his friends was at the office of the Sûreté, in a private room. Monk was a little late for the appointment; the party was already assembled round a table, and it gave him a final shock. He was not, indeed, surprised to see Crane and his daughter sitting opposite Forain, and he guessed that the man presiding, with the white beard and the red rosette, was the chief of police himself. But his head turned when he found the fifth place filled with the broad shoulders, cropped hair and ghastly handsome face of Valence, the younger second of Le Caron.

Old Crane was in the middle of a speech when he entered, and was speaking with his usual smouldering and self-righteous indignation.

"I send my son to execute a deed of partnership in a good business with Miller, Moss and Hartman, one of the first firms in the civilized world, sir, with branches in America and all the colonies, as big as the Bank of England. What happens? No sooner does he set foot in your country than he gets in a dicing, drinking, duelling gang, and is butchered in a barbarous brawl with drawn swords."

"Mr. Crane," said Forain gently, "you will forgive me if I both contradict you and congratulate you. Given so sad a story, I give you the gladdest news a father could hear. You have wronged your son. He did not drink, he did not dice, he did not duel. He obeyed you in every particular. He devoted himself wholly to Messrs. Miller, Moss and Hartman; he died in your service, and he died rather than fail you."

The girl leaned swiftly forward, and she was pale but radiant.

"What do you mean?" she cried. "Then who were these men with swords and hateful faces? What were they doing? Who are they?"

"I will tell you," answered the Frenchman calmly. "They are Messrs. Miller, Moss and Hartman, one of the first firms in the civilized world, as big as the Bank of England."

There was a silence of stupefaction on the other side of the table, and it was Forain who went on, but with a change and challenge in his voice.

"Oh, how little you rich masters of the modern world know about the modern world! What do you know about Miller, Moss and Hartman, except that they have branches all over the world and are as big as the Bank of England? You know they go to the ends of the earth, but where do they come from? Is there any check on businesses changing hands or men changing names? Miller may be twenty years dead, if he was ever alive. Miller may stand for Muller, or Muller for Moses. The back-doors of every business to-day are open to such newcomers, and do you ever ask from what gutters they come? And then you think your son lost if he goes into a music-hall, and you want to shut up all the taverns to keep him from bad company. Believe me, you had better shut up the banks."

Margaret Crane was still staring with electric eyes. "But what in the name of mercy happened?" she cried.

The investigator turned slightly in his chair and made a movement, as of somewhat sombre introduction, towards Valence, who sat looking at the table with a face like coloured stone.

"We have with us," said Forain, "one who knows from within the whole of this strange story. We need not trouble much about his own story. Of the five men who have played this horrible farce, he is certainly the most honest, and therefore the only one who has been in prison. It was for a crime of passion long ago, which turned him from being at worst a Lothario to being at worst an Apache. Hence these more respectable ruffians had a rope round his neck, and to-day he is not so, much a traitor as a runaway. If on that hideous night he held a candle to the devil, he is no devil-worshipper; at least he has little worship for these devils."

There was a long silence, and the stony lips of the shaven Apollo curled and moved at last. "Well," he said, "I won't trouble you with much about these men I had to serve. Their real names were not Lorraine, Le Caron, etc., any more than they were Miller, Moss, etc., though they went by the first in society and the second in business. Just now we need not trouble about their real names; I'm sure they never did. They were cosmopolitan moneylenders mostly; I was in their power, and they kept me as a big bully and bodyguard to save them from what they richly deserved at the hands of many ruined men. They would no more have thought of fighting a duel than of going on a crusade. I knew something of the countess, who has nothing to do with the story, except that I got them a short lease of her house. One evening Lorraine, who was the leader and the cleverest rascal in Europe, young as he was, happened to be turning over the drawer of curios, which he had taken out of the black cabinet and put on the round card-table. He found the old Italian ring, and told us it was poisoned; he knew a lot about such toys. Suddenly he made a momentary gesture covering the drawer, like a fence when he hears the police. He recovered his calm; there was no danger, but the gesture told of old times. What had produced it was a man who had appeared silently, and was standing outside the french windows, having entered up the garden slope. He was a slim, fair young man, carefully dressed and wearing a silk hat, which he took off as he entered. 'My name is Crane,' he said a little stiffly and nervously, and plucked off his glove to offer his hand, which Lorraine shook with great warmth. The others joined in the greeting, and it gradually became apparent that this was the representative of some firm with whom they were to make an important amalgamation. In the entrance-room all was welcome and gaiety, but when young Crane had followed old Bruno into the big inner room, leaving his hat and gloves on the card-table by the curios, I fancy things did not go so smoothly. I did not understand the business fully, but I was watching the three others who did, and I came to the conclusion that Bruno, in their name, was making some proposition to the new junior partner which they regarded as a very handsome proposition for him, but which he did not regard as altogether handsome in other respects. They seemed quite confident at first, but as the talk went on in the inner room Vandam and Le Caron exchanged gloomy glances; and suddenly a full, indignant voice came from within: 'Do you mean, sir, that my father is to suffer?' and then, after an inaudible reply, 'Confidential, sir! The confidence, I imagine, is placed by my father in me. I shall instantly report this astounding proposal... No, sir, I am not to be bribed.' I was watching Lorraine's face, that seemed to have grown old as a yellow parchment, and his eyes glittered like the old stones on the table. He was leaning across it, his mouth close to the ear of Vandam, and he was saying: 'He must not leave the house. Our work all over the world is lost if he leaves this house.' 'But we can't stop him,' whispered the doctor, and his teeth chattered. 'Can't!' repeated Lorraine, with a ghastly smile, yet somehow like a man in a trance: 'Oh, one can do anything. I never did it before, though.' He picked the poison ring out of the heap. Then he swiftly drew the young man's glove out of his hat on the table. There came a burst of speech from the inner room: 'I shall tell him you are a pack of thieves!' and Lorraine quietly slipped the ring inside a finger of the glove, a moment before its owner swung into the room. He clapped on his hat, furiously pulled on his gloves, and strode to the French windows. Then he flung them open wide upon the sunset, stepped out and fell dead on the garden turf beyond. I remember his tall hat rolling down the slope, and how horrible it seemed that it should still be moving among the bushes, when he lay so still."

"He died like a soldier for a flag," said Forain.

"Perhaps you have already guessed," went on Valence, "the rest of the story. Hell itself must have inspired Lorraine that night, for the whole drama was his and worked out to the last detail. The difficulty in every murder is how to hide the corpse. He decided not to hide it, but to show it; I might say to advertise it. He had been striding up and down the inner hall, his flexible face working with thought, when his eye caught the crossed swords on the trophy. 'This man died in a duel,' he said. 'In England he'd have died out duck-shooting, and in Russia of dynamite. In France he died in a duel. If we all take the lighter blame, they will never look for heavier; it's a good rule with confessions,' and again he wore that awful smile. He not only staged the duel, but the drunken quarrel that was to explain it. They were quite right when they said the champagne was not sent for till after the boy's arrival. It was not sent for till after the boy's arrival. It was not sent for till after his death. They carefully scattered cards, carefully threw furniture about and so on. By the way, they didn't shuffle the packs enough to deceive Monsieur Forain. Then they put Le Caron—the showiest—in his shirt-sleeves, did the same with the dead man, and then Lorraine deliberately passed the sword through the heart that had already ceased to beat. It seemed like a second murder, and a worse one. Then they carried him down in the dark, just before the dawn, so that no one could possibly see him save on the fighting ground. Lorraine thought of twenty little things; he took an old miniature of the countess from the cabinet and put it in the dead man's pocket, to put people off the scent—as it did. He left Mr. Crane's letter, because its warning against dissipation actually supported the story. It was all well fitted together, and if Le Caron hadn't put his foot on a cucumber-frame in the dark I doubt if even Monsieur Forain would ever have found a hole in the business."

Margaret Crane walked firmly out of the offices of the Sûreté, but at the top of the steps outside she wavered and might almost have fallen. Forain caught her by the elbow, and they looked at each other for a space; then they went down the steps and down the street together. She had lost a brother in that black adventure, and what else she gained is no part of the tale of the five strange men, or, as she came to call it afterwards, the five of swords. Margaret asked one more question about it, and their talk afterwards was of deeply different matters. She only said: "Was it the wound you discovered on his finger that made you certain?"

"Partly his finger," he assented gravely, "and partly his face. There was something still fresh on his face that made me fancy already that he was no waster, but had died more than worthily. It was something young and yet nobler than youth, and more beautiful than beauty. It was something I had seen somewhere else. In fact, it was the converse, so to speak, of the case in Rostand's play, 'Monsieur de Bergerac, je suis la cousine.'"

"I don't understand you," she said.

"It was a family likeness," replied her companion.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.