RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

The Pall Mall Magazine, October 1903,

with "The Lost Elixir"

A WEEK after I had passed my examination before the committee of the Narrative Club, which, as you may know, is an assembly into which none are admitted save those who have many wanderings to their account and are able to tell tales about them, I received a notice from the Secretary to the effect that he was in a position to accept my cheque in payment of my entrance fee, and, further, that he would be happy to introduce me to my fellow-wanderers at the usual monthly supper on the following Sunday, at 9 p.m.

"You are rather in luck as regards your introduction to-night," he said, when we met at his rooms. "According to the strict rules you would have been called upon to justify your calling and election by telling us a story; but it so happen that this evening will be the only one for nearly a year that we can get hold of a man who is perhaps our most distinguished member. You know him by name, and you may have run across him in some of your travels—Professor Hessetine."

Of course the world-famed name was familiar to me, as it is to everybody who has read anything outside novels and newspapers; but as I had had the great privilege of sitting at the same table with him a couple of years before on a West Coast boat from Panama to Lima—whither he was going to write a monograph on the prehistoric tombs of the ancient seaboard towns—the freemasonry of travel entitled me to claim acquaintance with him.

"Then that's all right," said the Secretary, himself a noted climber of hills and slayer of retiring beasts which affect the most neck-breaking localities to be found above the snow-line, when I had mentioned this: "he'll be delighted to see you again and have a chat about Inca-land with you. Personally, I am expecting quite a treat, apart from any story he may have to tell us; for he promised me, in his letter accepting the invitation to be the narrator of the evening, that we should be the first to hear of what he has done at Susa. Even before the scientific papers get it, I mean."

"If he does that I don't much care whether he tells us a story or not," I said. "I can hardly imagine any ordinary travel yarn that would be anything like as interesting as Hessetine on Susa."

"That, my dear fellow," he replied, with a smile, "is probably because you have only just become a member of the Tale Club, as some of our irresponsible globe-trotters have christened it. Oh, and, by the way, that reminds me," he went on, turning towards me, "there's just one hint I ought to give you. You'll have to expect some pretty tough-laid yarns at our distinguished symposia, but we have a tacit understanding as to the acceptance of the aphorism that truth is often stranger than fiction, and so we often give truth—and the narrator—the benefit of the doubt."

"That's nothing," I laughed: "I know some myself, perfectly true, which no British jury would believe if I told them on oath in the witness-box."

Now this was a true saying, but—well, if any one else than a man of European reputation had told Professor Hessetine's story and staked that reputation on its truth I should still have had my doubts as to the complete purity of his facts.

It so happened that during supper—by the way, a supper at the Narrative Club is quite the most delightfully free-and-easy meal inside the confines of civilisation—the conversation, led off by a young doctor who had just been making a long study of the so-called miracle-healing practised by the priest-physicians of Korea, turned upon the many well-authenticated traditions which exist among nearly all peoples belonging to the older civilisations as to the possibility of prolonging human life, and even youth, indefinitely by the regular eating of certain combinations of herbs, or the direct mingling of certain animal and vegetable essences with the blood.

I noticed that, although the Professor listened most attentively to the conversation, he only assisted it by an odd remark, always very much to the point, thrown in here and there, and every now and then an approving nod or a dissenting head-shake. When the table was cleared, and the chairman, according to custom, gave up the post of honour to the Narrator of the evening, it was not very long before we discovered that he had a reason for his reticence, for the first words that he spoke after the glasses had been filled and the pipes loaded were:—

"Fellow-wanderers by sea and land"—that is the usual formula of address—"I daresay you will have noticed that I have been exceedingly interested in the conversation which took place during supper. It is of course, a most absorbing topic for all students of human things who are able to approach the most impossible-seeming subjects with that perfectly open mind which, as most of us believe, only long study and extensive travel can give. But whether it be what is commonly called a coincidence or not, I may as well preface the story I am going to tell you by saying that it bears with exceeding closeness upon that very subject."

While the Narrator was saying this he seemed to some of us, certainly to myself, to have grown—I was almost saying—centuries younger. That, however, was not quite what I mean. He might himself have been of any age, clime, or nationality, and his features and expression had suddenly undergone a subtle change which seemed a reversion to some former state of being. In other words he appeared to transfer his personality from the present into that remote epoch of which he was going to tell us—an epoch of which he certainly knows more than any man alive—that is, as far as we know, now alive.

"You must not think," he went on, perhaps having noticed a certain involuntary lifting of eyebrows round the table, "that I am going to tell you that since our last meeting I have had the privilege of making the acquaintance of the Flying Dutchman or the Wandering Jew, although I fear I shall have to make an almost equal demand upon your credulity—for, gentlemen, I am going to ask you not to disbelieve me when I tell you that I, who am speaking to you to-night with the lips of flesh, only a few-weeks ago spoke, also in the flesh, with one who, as I have every reason to believe, lived and toiled, loved and thought in the long-buried city of Susa in the far-off days when Rameses the Great was king."

In any other assembly such a tremendous announcement, coming in all seriousness from the lips of such a man, would have been received with what the reporters are accustomed to describe parenthetically as "sensation"; but among the Wanderers by Sea and Land not an eye winked. Only a deeper silence fell upon us as we waited for the Professor to continue.

"I may presume," he went on after a little pause, "that you all know I have just returned after some months' work in connexion with the excavations at Susa, one of the buried cities of Upper Egypt, which appears to have been a sort of pleasure resort on the shores of a now vanished lake, to which the aristocracy of Thebes were accustomed to go as Londoners and Parisians now go to Homburg or Aix. Indeed, as a matter of fact, I am now quite certain that this was so, for I have in my possession an absolutely unique treasure in the shape of a complete plan of it, illustrated with drawings of its principal buildings, from the hand of one who saw it in all its pride and beauty.

"This is, however, a slight anticipation. I have the plan with me, and you shall see it afterwards. I was engaging my staff of skilled diggers and excavators—quite a different class from the common fellah labourers—at Memphis as the best men are nearly always to be found there; and one day, when I had almost completed my staff and was thinking of making a start northward, I was taking my usual evening stroll among the ruins to the north of the modern city, when I was considerably startled by hearing a man's voice speaking in strangely musical tones and in a tongue totally unknown to me. It came from the other side of the fallen statue of Rameses at the back of which I was leaning, smoking a contemplative pipe.

"I say that I was startled, because I think I may affirm without boasting that I am familiar, not only with all the dialects spoken in the Nile Valley, but with most of the languages of the far and near East. Yet I searched my memory in vain for the recollection of a single syllable or inflection, until I heard him say quite distinctly, and yet with an accent and intonation utterly strange to me, the words, or rather the exclamation, 'O Rameses, Rameses!'

"No one could have pronounced the name with such exquisite purity and such profound depth of feeling—I had almost said sorrow. Gentlemen, I am not ashamed to admit that in that moment a keen thrill of awe passed through my soul, for the accents seemed to awaken some long-stilled echo of a memory belonging to a life that had been lived in other ages, and with it came the thought, I know not whence, that I was listening to a speech that human lips had not uttered for nearly thirty centuries.

"I put out my pipe and went round the base of the statue, and there I found myself face to face with such a man as I had never set eyes on before. He might have stood as model to the sculptor who designed the statue beside which we were standing. There was the broad, square, low forehead, and under it looked out at me the large, level-set eyes that might have belonged to the Great King himself. The straight, massive nose, the full, delicately-curved, sensuous lips and the firm, commanding chin—I recognised them all, and the whole countenance wore that almost indescribable expression of contemptuous repose which is so inevitably characteristic of the royal race of Old Egypt.

"He did not show the slightest sign of surprise at my appearance. His eyes looked too weary with seeing for that.

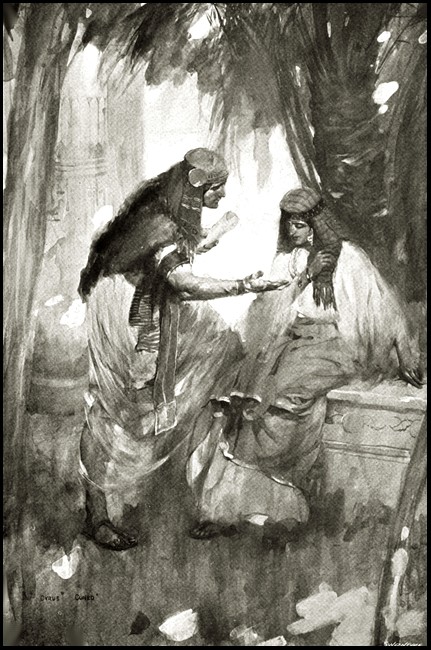

"He did not show the slightest sign of surprise at my appearance."

He returned my salute with a grave dignity that was, even there, in strange contrast to the scanty rags and the frayed and faded cotton shawl which hung from his shoulders. I addressed him in Arabic—for somehow the pure and ancient speech of the desert suggested itself as the most fitting medium at my command—and asked him if he would do me the favour of telling what language he had been speaking when I had unintentionally overheard him a few moments before. He replied, in Arabic which was far more fluent and idiomatic than my own:

"'That, Effendi, was the speech in which my brother Rameses, by whose time-worn effigy we stand, wooed our cousin Nephert-Anat, the star-eyed Lily of the Upper Nile, in the days when the desert that has buried our glories laughed and sang with the joy of its fruitfulness and Egypt was Queen of the Earth.'

"Now, you are very well aware, gentlemen, that insanity, in its milder and more inoffensive forms is not regarded in the East as it is here. It is treated with tolerance and by most people with respect as a sign of the special protection of the Deity. You will, I am sure, understand me when I say that my new acquaintance's first utterance inclined me to the belief that he was a scholar whom over-study and under-feeding had made mad. But there was no sign of madness in the calm, luminous eyes which looked so steadily into mine while he was making this extraordinary speech. There was none of the restlessness of the feet and hands, or the sideway movements of the head, which are the almost certain accompaniments of insanity. On the contrary, his attitude was easy and yet full of dignity, and his manner was rather that of a man who is uttering a commonplace which has become wearisome to him.

"I, of course, realised at once that no good end could possibly be served by any show of incredulity, and so I replied just as seriously as he had spoken: 'Truly, then, O brother of the Great King, since thy days have been prolonged on earth so far beyond the common span of mortal life, great must be the blessing or grievous the curse that the High Gods have laid upon thee. Is it permitted that a stranger from a far-off land should ask thee why the shade of thy mighty brother hath waited so many cycles for thee in the Halls of Amenti?'

"'Ah,' he exclaimed, bending down towards me—for, as I have said, he was a man of splendid stature, fully a head taller than I am—and bringing his eyes to a level with mine, 'dost thou believe me, then? or is it only thy charity which thus listens with a show of credulity to what thou, like the others, takest for the idle tale of a madman? Speak truly, Effendi, as thy soul liveth, for on thy faith hangs the fate of one who, in the days that are forgotten, by his own rash and presumptuous act, brought upon his soul the anger of the High Gods and cut himself off from the common lot of man.'

"I confess that I was strangely and deeply moved; and I replied, as though some inner impulse had been prompting me: 'O Egyptian, who am I, the child of yesterday, that I should say what is and is not possible to the might of the Gods? Shall the sand-grain by the seashore say to its fellow, "With thee and me the limits of Ocean end"? I would make no trespass on thy confidence, yet if thou hast the will to tell me, thy story will not fall on idle ears, and when the proof is given belief shall not be wanting.'

"'It is just,' he said, his lips making the faintest movement of a smile. 'Yet it is well said that trust is twofold. Will the Effendi trust me in a small matter if I will trust him in a great one?'

"It may seem to you like a piece of arrant foolishness in an old traveller, but I positively could not distrust the man, and so I answered: 'So far as it is lawful and fair dealing between man and man, Egyptian, I will trust thee to the half of my goods.'

"'I have no need of thy goods, Effendi,' he replied, with a sigh which was the saddest I have ever heard from a human breast: 'I who have feasted with kings and conquerors and scattered gold and jewels to the four winds of heaven till wealth became as dross in my hands and I had sickened of all that earth could sell—what is thy poor little fortune to me? Yet it is because I am what men call poor in money that I would ask for thy faith and thy help. The matter is in this wise. Thou art going to Susa, the city of my youth and my happiness, and the scene of the crime against the High Gods which made the one unfading and destroyed the other for ever. At Susa thou wilt seek to clear the dust of ages from the house in which I and mine dwelt, the temples in which we worshipped, and the tombs where the mummies of my dear ones are resting, while I, self-doomed, count on the countless suns of endless days. Now, what I ask is this: that thou shouldst make me one of thy company, the meanest of them if thou wilt, and take me to Susa, and there I will show thy workmen where to dig that they may find that which thou seekest. I will draw thee pictures of the temples and the theatres and the tombs, and mark out the streets and squares, until all Susa in its ruins shall be as plain to thee as it was in its glory to me.'

"I don't suppose that any archaeologist had ever had such an astoundingly tempting offer made to him, and I candidly admit that I was not only tempted—I fell. But there was still the undeniable fact that, under all known human conditions, such a thing was absolutely impossible. Certain doubts, too, which I will come to shortly, had occurred to me while he was making his proposition. Still, all said and done, I stood to risk nothing but his railway fare and keep—I was already risking them and absurdly high wages too for men not half as likely-looking as my strange friend—even if I was only able to use that commanding air of his by making him an overseer, so I held out my hand, and said:

"'It is agreed, Egyptian. To-morrow we start by the train that leaves at sundown. Come to me after the early coffee, and I will tell the dragoman and the overseer that I have engaged thee. After the paper is signed I will advance money to buy what thou hast need of. Then in thine own time thou shall make plain those things which are now dark to my eyes.'

"Our hands met. As I believe now, it was a grip which drew two living men together across a gulf of thirty centuries. That strikes you, no doubt, as a somewhat fantastic and far-fetched notion, but I am not without hope that your opinion will change when you have heard my reason for believing as I do."

The Professor, who had so far told his extraordinary story in the most commonplace conversational tone, paused and took a draught from a great tankard of lager before him. The silence was so strained that no one seemed to care to break it, even to get a drink. When he put his tankard down and faced us again, some of us began to find a sort of likeness in those symmetrically-cut features of his to others that we had seen on the wall-paintings at Luxor and Karnac and other familiar places on the now, if possible, vulgarised Nile, as well as on the mighty carved monoliths which even now raise their giant bulk above the sands of time, changeless in the midst of change, silently contemptuous of the roar of the noisy centuries and the chatter of their yesterborn children.

"During the journey to Thebes," he went on, just as quietly as before, "my friend the Egyptian took his place among the other men in my employment, and scarcely exchanged a score of words with me. This was, of course, perfectly natural. In the East master is master and servant is servant, and there are no board schools. But as soon as we had left the train at Thebes and began to prepare for crossing the fifty-odd miles of desert to the site of what once was the pleasure-city of Susa, a sudden change came over him. Those of you who have seen a man breathing his native air after years of exile will understand what I mean. He began to exert a sort of unofficial authority which not even the dragoman or the overseer tried to resist after the first few hours, during which they somehow learnt that he was at home and they were not.

"We reached the semicircle of granite hills under which the long-dead citizens of Susa once found protection from the worst of the desert winds, during the second march of the third day. We chose our camping-ground and pitched our tents. After supper I took my pipe and went for a stroll round the encampment, to see that everything was ship-shape. There was such a moon in the sky as one only sees from the desert; and when my inspection was over I wandered towards the edge of the bay of smooth sand, broken by outcrops of stone which were for vanished Susa what the Monument and Nelson's Column may some day be for London—if they last as long.

"I had not gone far from the camp when I heard close by me the grave, gentle voice of my Egyptian saying, still in the classic Arabic of the Koran:

"'Effendi, thou hast kept thy part of that which was agreed between us. This is Susa, and my eyes already see the flood of ages rolled back, the sands swept away, and the likeness of the temples and palaces once more reflected in the blue mirror of the lake which washed their everlasting walls. Diana, as I have heard the old Greeks say, is smiling full-eyed on us to-night. Hast thou the leisure and the will to learn why Pent-ar, priest of the Royal Blood in the House of Amen-ra and Writer of the Sacred Records, sought thy help and charity to return to the place of his birth?'

"I confess that I started a little at the mention of that name, so famous to all Egyptian scholars, by the lips of a living man who claimed it as his own, but I managed to tell him in my usual tone that if he was prepared to give me his confidence I was quite ready to receive it; and so I sat down on a huge slab of granite, and he, declining with a graceful gesture my request that he too would be seated, stood before me, a strangely eloquent figure in the bright moonlight, and told me his story with a simple dignity of diction and expression which, translating from his exquisite Arabic as I am, I cannot hope to emulate.

"'My history, Effendi,' he began, after a long look over the wilderness of ruins, 'shall be brief, since no man could tell even in many hours the narrative of the changing ages. And first I will explain what may have seemed strange to thee—that I, who, as I told thee at Memphis have squandered uncounted treasures should be too poor to pay my way here and do the work for myself which I am to do for thee. It comes about in this wise. Not many months ago I learned from such a seeker as thou art for the hidden glories of my people that a certain papyrus had been found at Thebes which was of the time of the Great King and a little after, and signed by one Panit-Ahmes, priest of Sechet and scribe of the College of Physicians at Thebes. Further, I was told that this papyrus, which is now in your great Museum of London, contained certain passages which, though plain to decipher, had no outward meaning, and contained, moreover, characters which the most learned of those skilled in the writing of the old Egyptians could not make words or phrases of.

"'Now in the days of the Great King this Panit-Ahmes shared with me the fame which in those days was greater than that which men could win with bow and spear, the fame of learning and of the knowledge of hidden things. This of itself, though it might have made us rivals for the favour of the High Gods would not by necessity have made us enemies; but there was that between us which hath set man's hand against his brother since first the world began—the love of a fair woman.

I divined instantly that the passages which your scholars could not read were written in the Hermetic character which was known only to the initiates of the Sacred Mysteries and that, since this lore has been lost for many ages there was no other on earth who could read them save myself.

"'That day I sold a few curious jewels, the last of a once great store, to the explorer, bought myself some clothes of the European fashion, and took passage to London. As I can speak your language, as I can all others which I have seen come into being since my nurse taught me the ancient tongue of Khem, I went to the chief keeper of manuscripts in your Museum and offered to translate this papyrus for him, though in doing so I was breaking the oath of my initiation, so strong upon me was the desire to learn what Panit-Ahmes had hidden in the Hermetic passages.

"'He looked on me at first in wonder, as thou didst, Effendi, when we stood that evening by the statue of Rameses; but there was unbelief as well as wonder in his eyes and his speech, so I went to a case in which some papyri of the time of the Second Amen-ho-tep, who took the great city of Nineveh, rested, and these I read off into English as quickly as you, Effendi, would translate from an Arabic writing. Then he believed, but his wonder grew greater; and in the end, after much talk and writing to many people, as is the fashion of the English, the permission I craved was given to me, and in a day I made the translation and a copy of the Hermetic passages for myself. The scholars of the Museum were greatly amazed, and offered me a high stipend to remain and work for them; but how could I, Pent-ar the Initiate, take money for the revealing of the Holy Mysteries to unbelievers? Also, I had deceived them, for the meaning I wrote down of the mystic sentences was not the true one. Had I written that, they would have laughed at me, and I should have broken my oath for nothing.

"'Now the meaning of the passages was this—and by it thou shall learn, ere many days have passed, whether Pent-ar the Scribe hath told thee the truth or a lie:—

"'0 thou who in the days to come, shall be weary of the burden of years: Behold, my hate shall be buried in my tomb, that I may greet thee as friend in the Halls of the Assessors.

"'When the High Gods, whose holiness thine impiety hath outraged, shall Judge thy cup of penance to be full, it may be that thine eyes shall see this writing, which thou alone of men will in those days be able to read with understanding.

"'Then shalt thou learn that the flame lit in thy veins by the Elixir of Long-Drawn Days may be quenched only by the dew which thou shall find even then moist on the waiting lips of Love. It was given to me to learn the secret of the poison which was the antidote to the venom of endless days. Thy mistaken love bound her soul in the flesh-fetters which through ages of weariness thou shall learn to curse. My love gave her rest.

"'From her lips, in the good time of the High Gods, it may be given to thee to drink the Elixir of the Lesser Death. On the green shores of Amenti we wait and pray for thee.

"'Effendi, thou hast already heard the story of Pent-ar, for beyond the recital of the Passages of Panit-Ahmes—once my rival and enemy, and now my friend and only hope—there is little to tell that thou hast not already guessed.

"'In many climes and ages I have seen men seeking the essence which they in their ignorance called the Elixir of Life. I could have given it to them, as I could give it to thee if I wished to repay thy friendship with a curse; for it was I who, guided by the malice of the Infernal Gods discovered the reality of which they were seeking the shadow, and the manner of finding it was this:—

"'When the Great King was building the Hall of Seti at Luxor, many structures were cleared away to make room, and great excavations were necessary for its foundations. In one of these I, when, as Keeper of the Records examining the ground that no hidden sacred place might be violated by the workmen, found a very ancient temple, so old that it was buried in those days even as Susa is buried in these. By virtue of my office I passed into it alone;—would that my feet had rotted to the ankles before I had crossed that fatal threshold! In the inmost sanctuary, in the place of hiding behind the chief altar, I found a golden casket of scrolls which, as was my right, I took home with me, that I might if possible discover new secrets amongst their contents. That which I sought I found, and more.

"'Fastened by a blood-red seal to the smallest of the scrolls was a great emerald wrapped in many folds of leaf of gold. The scroll, deciphered after much labour, told me that it was hollow, and that its cavity was filled with the Elixir of Long-Drawn Days. "O thou," ran the scroll, "whose learning shall teach thee the meaning of these words: know that the Elixir of the Emerald is the last of the secrets of the Infernal Gods vouchsafed to man. If thou hast courage, and wouldst outlive the changing ages, thyself unchanged amidst them; if thou wouldst see the generations of men pass away like shadows from the bright morning of thine eternal youth, mingle but a drop of this ichor—which is the tears of Isis with thy blood, and never shall it be chilled with frosts of age, nor its flow arrested by the hand of Death. Dost thou love? Then shall one drop more in the veins of thy beloved give thee and her the delights of quenchless love and deathless passion as long as the ages last. Immortal—the Infernal Gods greet thee!"

"'Alas! Effendi, I loved, and through my love I was lost.... I would fain spare myself and thee, Son of the Younger Days, the story of that which was the same then as it is now, and as it shall be when the last son and daughter of man pledge their troth on the brink of the common grave. Let it therefore suffice to say that Amaris was in my eyes even fairer and more desirable than her sister the lovely Nefert-Anat herself, who was honoured by the love of the Great King. Endless days of fadeless youth with her—what more could the Gods themselves give me? I took the elixir in my satchel one evening when I was to walk with her through our favourite paradise among the palms. I read the scroll to her and showed her the emerald. Then I tempted her as I had been tempted, and because she loved me I won my way with her.

"I read the scroll to her and showed her the emerald."

"'Soon afterwards we were married, for I was of the Royal Blood and Panit-Ahmes was not. Moreover Rameses and Nefert were my friends and pleaded my cause well. My rival cloaked his wrath and his hate under a guise of resignation, but the fires burnt still in his breast and well-nigh consumed him.

"'On our marriage-night I instilled the elixir into my veins and hers and we went to rest dreaming that, as long as the sands of time should run, for us all nights would be like this, all mornings like the morrow. The next day, in the boasting pride of my happiness and triumph, I told Panit-Ahmes of what I had done, and then, telling him that I and my Amaris alone of the sons and daughters of men, should live and love for ever, I flung the emerald and what was left in it of the tears of Isis far out among the brown waves of the Nile.

"'What hidden lore Panit-Ahmes may have known then or discovered later I know not, but he laughed when he saw me throw away what kings would have given their dominions for, and told me that since I had kept part of the curse of the Infernal Gods for myself I was welcome to do what I would with the rest. "As for Amaris thy wife," he said, as he turned away from me, "I have loved her, and I will save her from the doom that thou shall some day pray the High Gods in vain to take away from thee."

"'For a year, Effendi, I was happy—happy, perchance, as no other wedded lover has been since then, for that year was to me only the first of the countless years which should all be as bright as it was. Then Panit came to me, and told me that he had found in a dream, which was a revelation from the High Gods the secret of the antidote to the tears of Isis. I laughed him to scorn, so marvellously had the elixir renewed my already fading youth within the short space of a year. I boasted that I would drink a measure of it as I would a draught of the red wine of Cos but he flung my laugh bark at me, saying that since I loved the life of the flesh so well, I should live it. It was not for me, but for Amaris that she might lay down the burden of living when the Gods pleased or she was weary of carrying it.

"'Then said I, in my pride, "0 Panit-Ahmes Amaris will be singing the songs of youth in the days when thy mummy is dust. Let her drink if she will. She is my most precious gift from the Gods; thou canst not take her from me."

"'Never was vainglorious boast more bitterly requited, never was boaster made more humble than I was. Amaris full of faith and vivid life as I was took the hazard of the draught laughingly, and seemingly was none the worse for it. Yet another year had not gone by before she sickened of a fever that followed a low Nile, and died. Mad with grief, I took the lever too, and for many days lay in delirium. When I returned to health and reason, the mummy of Amaris already lay in its place in the City of the Dead, over yonder behind the northern spur of the hills, and Panit-Ahmes too was dead, and had taken his secret with him over the River of Darkness into the Land of Shadows.

"'Effendi, my tale is told, nor will I weary thee further by telling thee the awful story of the years that have passed between then and now. I have seen the races of men come and go, and their empires wax and wane. I have seen altars rise and fall, faiths born and die, like shadows drifting over the eternal sea. I have learnt the vanity of human things—the shame of glory and the poverty of wealth and the dream of dominion—and here I stand before thee, poor and lonely, without a friend or a lover among all the myriads of men, weary of living, and asking only of the High Gods and thee to find the tomb of Amaris, that I may lay my lips on hers, and from them receive the sweet summons to join her waiting shade on the green shores of Amenti.'

"Such, gentlemen," continued the Professor, laying down a few slips of paper which he had used every now and then to help his memory, "such was the extraordinary story which I heard under such singular circumstances amidst the ruins of Susa. I will tell you the sequel to it in as few words as possible, for I must confess that my theme has somewhat run away with me. Marvellous as it may seem to you, I must ask you to accept it as I saw it and as I tell it to you. There are some things which do not admit of discussion or explanation, and I think you will agree with me that this is one of them.

"Pent-ar was as good as his word, so far as his knowledge of the totality went. The precision with which he indicated the course of the streets and the positions of the hidden buildings was little short of miraculous. For upwards of a month he possessed his world-weary soul in patience, until he had completed the plan of which I spoke some time ago. When he brought it to me, soon after sunrise one morning, he said, with that strange, joyless smile of his:

"'Effendi, have I kept faith with thee? Have I promised aught that I have not performed? If thou art content with me give me now my freedom, that I may go and seek the tomb of Amaris.'

"My answer was an order to my overseers to move the camp at once under his direction to the City of the Dead. Once there, his whole manner changed. His eyes burned with the fire of an eager anticipation, and he worked with pick and shovel harder than the best of the labourers. At the end of a week we had laid bare a small pyramid, the apex of which, only showing a couple of feet or so above the sand, he had found with unerring instinct or memory after an hour's survey of the wilderness of ruins amidst which it stood. Just before sunset on the last day he came to me with two lamps in one hand and a powerful crowbar in the other.

"'My friend,' he said, using the term for the first time, 'Pent-ar has come to bid thee farewell. The tomb is found, and Amaris waits for me within. I go to open the way to her. If thou wouldst see with thine own eyes the proof of the things which I have told thee, come with me now to the Gate of Death. But bring all thy courage with thee, for it may be thou wilt need it.'

"'I will come, Pent-ar,' I said. It did not seem a time for more words, so I took one of the lamps and followed him to the tomb in silence. It would have taken my workmen hours to remove the great stone slab which closed the entrance; but he, evidently knowing all the secrets of the lost art, laid the passage open in less than an hour. Still silent, we went in, he leading. After I had counted twenty paces the passage ended in a chamber about twelve feet square and fifteen high. In the middle of it, on a huge cube of polished black marble, lay two splendidly adorned sarcophagi. One was open and empty, the other closed.

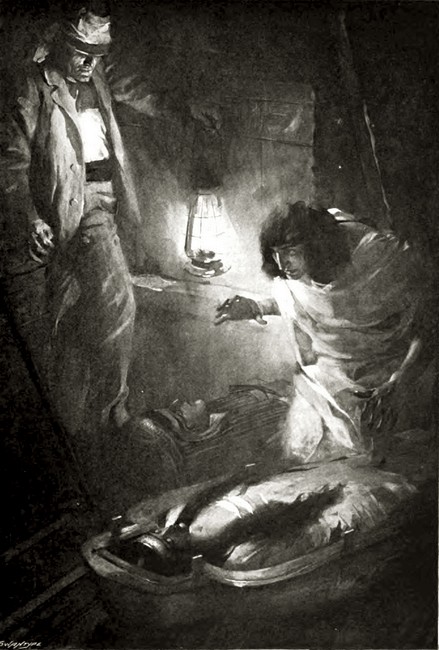

"'The resting-place of him who died not,' Pent-ar whispered, holding his lamp over it. Then he gave the lamp to me, and set to work with a chisel and mallet, which he had picked up outside the pyramid, on the lid of the other sarcophagus. When he had loosened it I helped him to raise it. A mummy-case lay inside, and this with reverent hands we lifted out and laid across the end of the stone. For a moment Pent-ar stood beside it, with hands raised above his head, and murmured in the ancient tongue what was doubtless a prayer for forgiveness and the favour of his outraged Gods. This finished, he took his knife from his belt and with a few deft silent movements detached and removed the cover of the case.

'"Amaris! Amaris!' he murmured again, falling on his knees beside the case, and saying some more words in his own speech.

"Amaris! Amaris!" he murmured again,

falling on his knees beside the case.

I looked over his shoulders, and to my amazement I saw, not the mummy I had expected to find, but the unswathed, white-robed figure of an exquisitely beautiful girl, who, instead of having lain there hidden from the sight of men for thirty centuries, might have fallen asleep only an hour before.

"'It is time,' said Pent-ar, rising and taking my hands. ' Is she not beautiful, my love, my bride? See, are not her sweet lips moist still with the dew of love, as Panit said? Now farewell, Son of the Younger Days and last of my friends on earth. In a few moments Pent-ar will be walking in the groves of Amenti hand in hand with Amaris. Farewell, and let not thy courage fail thee in the presence of Death the Releaser.'

"As I pressed his hands and bade him farewell, a flood of memories swept over my soul, I know not whence. Was it possible that I, with other eyes had once looked with love on that fair face? Who knows? But before I could frame the question I would have asked Pent-ar, he had stretched himself lengthways over the case and pressed his lips to those of his dead love.

"Gentlemen, I hope I may never see such another sight as that which I beheld in the next few moments. No sooner had their lips met than the fair flesh of the mummy grew dark and shrivelled into a thousand wrinkles. The eyes sank back into the sockets, the gloss faded from the gold-brown hair, and the rounded form shrank together under the garments. But even this was as nothing to the awful change which the magic of the Death-kiss had wrought on Pent-ar. He who a moment before had stood with me, a living breathing man, holding my hands and speaking to me in his now familiar voice, became, as it were in an instant, not a corpse, but a skeleton covered with a dry brown skin, through which the grey bones broke their way as they dropped with a gentle rustling sound into the case in which the ashes of the long-parted lovers at length were permitted to mingle.

"In my wonder and horror I dropped the lamps I was holding, and when I had groped my way into the outer air I found it full of flying grains of sand. I fought my way, half choked, back into camp. That night the worst sandstorm I have ever seen raged until morning, and when I was able to go luck to the City of the Dead I found nothing but a wide, level plain of driven sand where our excavations had been made. It was the winding-sheet of Pent-ar and Amaris and beneath it their ashes shall, I trust, rest in peace until the dawn of the day whose sun will never set."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.