RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

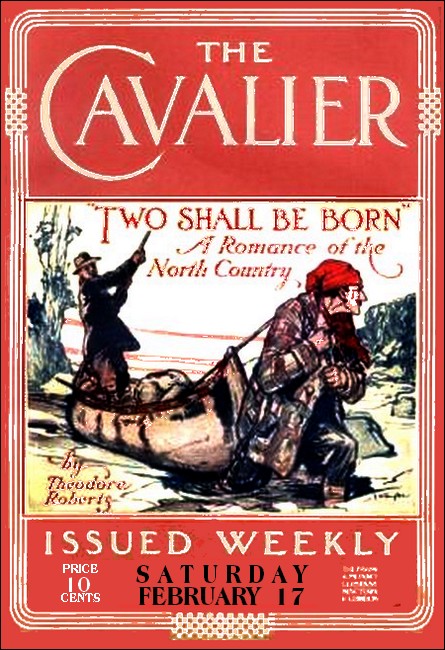

The Cavalier Magazine, 17 Feb 1912,

with first part of "The Occult Detector"

THE clock in the tower of the Record struck two. Although I didn't know it then, the clock of my destiny struck at the same time.

Hard on the throb of the chime Smithson stuck his head out of the door of his den, and swept his eyes over the local-room. He found nobody but me. Every one else was absent. As for me, I was having a smoke after a light lunch, and waiting for something to do.

"Nobody here but you, eh?" said Smithson. "Well, c'm'ere."

Smithson was city editor of the Record. Therefore, I cast aside my cigarette and complied with his request.

He bobbed back into his room, withdrawing his head from the door very much like a turtle drawing into its shell. I followed him and stood waiting his next remark. When it came I didn't know just what to make of it after all.

Said Smithson: "Know anything about Semi Dual?"

You couldn't bluff with Smithson. I shook my head and told him the truth. "Nothing," I said shortly. "Is it a newspaper or a race-horse, or what?"

Smithson grunted and rummaged among the papers on his desk for a moment, found some sort of memorandum and finally deigned to reply. "It's a man," said he.

"Funny name," I remarked, for lack of anything else to say.

"From all accounts he's a funny man," Smithson came back. "Now see here. Some two months ago this fellow came here and takes quarters in the Urania. I understand he has a full floor up there. He lives there, and beyond that I can't find out anything about the chap.

"Nobody seems to know what he does for a living, or if he does anything at all. Yet it seems from the reports of the elevator operators that quite a few folks call to see him every day. Well, that's about all. Shove some copy-paper into your pocket and go up and get an interview. There may be a story in the thing. Maybe we can make a Sunday feature out of it if it's any good."

"From his name he might be an Oriental fakir," I remarked. "Dual is suggestive at least."

"How?" said Smithson.

"Why, Dual—Do All."

"Maybe he does," said Smithson, not even grinning. "Find one."

He began to rummage among his papers again, and I went out and down to the street.

It was a hot day, and I felt no particular interest in my assignment. "Semi Dual," I muttered as I turned toward the Urania, a couple of blocks away, and I confess I managed to put no small contempt into my speaking of the words.

Thoroughly convinced that Smithson had started me out on the trail of some successful charlatan, who would reap a lot of free advertising from my story, I trudged grudgingly toward my task.

The Urania was the last word in modern office buildings, and had been open for something like six months. Twenty stories it reared its walls above the pavements, not to speak of the tower which surmounted the immense pile.

The first thing of interest that struck me as I walked toward it was that this particular individual I was going to see should be allowed to dwell as well as office there. I had understood that there was an iron-clad rule against anything of the sort.

I began to wonder if the Semi chap might not prove of some interest after all. Surely he must be possessed of some unusual influence to gain such a concession from the owners, as he evidently had.

I passed into the magnificent foyer of the Urania, and stopped for a moment to gaze at its chief adornment, a magnificent portrait-bust of Urania Marsden, deceased wife of the principal owner, who had given her name to the great building which he had reared. And then I started for a cage which would take me up to Dual's floor.

It occurred to me that I might as well find out any little thing about my prospective interviewee which I could pick up, and with that in mind I turned to the cage-starter and inquired the location of the man I sought.

"Semi Dual?" repeated the starter, as he clicked a cage away. "Dat's de ginny who lives on de roof."

I guess I showed my surprise, for the starter grinned.

"Dat's right," he continued. "He's got a three-year cinch on de whole tower an' de roof. He owns all of dis shack from de roof up."

"How do I get there?" I inquired.

"Take de cage to de twentieth, an' den walk," said my informant, and waved me to a car which had just come down.

I entered and leaned against the grill at the back of the car. More and more my errand began to assume the unusual…. I had never interviewed a man who lived on a roof. I began to think that I might enjoy this experience after all.

The car I was in was express, and made only four stops on the way up, so that I was still lost in a somewhat puzzled expectation when we stopped at the top floor, and the operator in response to my interrogation, waved his hand to a flight of stairs. I walked over, and stopped to examine these more closely before going up. They were a most surprising pair of stairs.

In most large structures like the Urania, the steps leading to the roof are for the use of occasional employees only, and are apt to consist of mere concrete or steel, or both, but there was an exception here. These steps were faced with marble, inlaid on their treads with beautiful tile arabesques, and railed in carved and twisted bronze.

They looked more like the grand staircase of an entrance-hall than a flight of steps leading to a roof. In front of them stretched the skin of an immense lioness, perfectly mounted and preserved, and each massive newel was surmounted by a life-size figure in bronze, holding an opalescent globe of glass, evidently a light.

All my former grouch over my assignment vanished, and I placed my foot on the first step of the stairs with much the same feeling of pleasant anticipation which must assail any one who finds the unexpected among the commonplace, and realizes that there is a promise of more to come. So with growing interest I mounted the stairs, and paused at the top with arrested stride.

I had stepped into a garden such as I had never seen or dreamed of before.

Straight before me ran a broad approach to the door of the tower, flanked on each side by shallow beds of flowers, set out in broad boxes of earth, and interspersed with small trees and shrubs. Other narrower passages led off in different directions, toward the high parapets of the buildings which were covered with climbing vines.

I smelled the breath of roses, and half forgot for the time that I was twenty stories above the busy streets. I seemed rather to be in a semitropical garden than on any roof of any building in the world. I stood for a moment and started to go on, only to pause again, before an immense inlaid plate in the floor. It was apparently of metal, inlaid with variously colored glass, set in the form of letters, which I stopped to read:

Pause and consider, oh, stranger. For he who cometh against me with evil intent, shall live to rue it, until the uttermost part of his debt shall have been paid; yet he who cometh in peace, and with a pure heart, shall surely find that which he shall seek.

I read and looked about me, almost as one dazed. The thought flashed across me that I was in the abode of some crazy fanatic. Pleasant anticipation gave place to a feeling almost of foreboding. Then I laughed, and set my hat more firmly upon my head. After all, I was in the twentieth century and it was broad daylight.

The sentence inlaid in the plate might be rather creepy, but going back empty-handed to Smithson would be far worse. I knew what I'd get from Smithson. I resolved to explore the mystery of Mr. Semi Dual.

Wherefore, I stepped out across the plate, planting my feet upon its prismatic surface, and at once a low, sweet chime, as of distant church-bells, broke on the afternoon silence of the roof. Rather hastily, I got across, and went on up the passage to meet a very conventional gentleman's man, who had opened the door of the tower and stood awaiting my approach.

This party silently conducted me into what was palpably a reception-room, took my card, and disappeared through an inner door, returning shortly with a silver tray upon which was a long glass of purest crystal, containing a liquid in which floated some tinkling bits of ice. This he deposited upon a small table which he wheeled to my side. "The day is hot, sir," he suggested. " You will find this very refreshing, I think." He withdrew with a bow.

When I came to think of it I was both thirsty and hot. The glass on the tray looked very inviting. I stretched out my hand and lifted it, smiling at this most unusual manner of receiving a representative of the press.

I touched my lips to the iced fluid, and experienced a heretofore unknown delight. To my palate, it seemed that the very essence of all the flavors of the fruits of all known varieties was slowly passing over my heated tongue. I didn't even try to imagine what the stuff was, but took first one swallow after another until the drink was half done. Then I set the glass down, and sighed, and looked about the room.

There was nothing unusual there, unless its very simplicity might have been so called. It was just a plain reception-room, such as one might have found in the suite of many a professional man.

The rug on the floor was a monotone, of a hue between orange and brown, but of a quality which I had seldom seen. My feet sank into its pile as into a soft, shallow drift of snow. The chairs and tables while plain in every line, were of fine woods; the few engravings on the walls were undoubtedly genuine.

Severe simplicity was the key-note on the whole, but a simplicity combined with the nth degree of fineness in the materials used in bringing the effect about.

I drained the rest of my drink, and set the glass down. On the instant, as though my act had been a signal, the silent servant reentered the room. "If you have quite finished," said he, "Mr. Dual will see you now." He opened a door and stood aside for me to enter.

I ENTERED that room with a preformed wrong conception.

Just what I expected to see, or what sort of individual I expected to meet, I hardly knew. Now, in looking back, I fancy I half anticipated a sort of semi-Oriental setting at least. The man's name had been largely responsible for that.

Whether I expected an atmosphere of incense, an individual in cap and gown and Turkish slippers, or what, I can hardly make up my mind even now.

At any rate, the reality came upon me almost as a disappointment, at the very first, for the room might have been the private consulting-room of any successful lawyer or physician for all the furnishings showed, and surely the splendidly formed man who rose as I entered and greeted me with a delightfully reserved courtesy might have been none other than the doctor or lawyer himself.

Six feet he was, if an inch, yet so perfectly proportioned that he gave an impression of being merely large, rather than tall. His brown hair was carefully trimmed and brushed up from a broad brow, and even his perfectly kept imperial could not disguise the strength of the lower jaw.

But it was his eyes which arrested me in that first moment of meeting, and have held me ever since. Everything else was nothing save what any one might encounter anywhere in his daily walk. There are hundreds of well-proportioned large men in every large city, hundreds of men with strong jaws and faces, hundreds of men even with a peculiar warm olive tint to their skin, but never have I seen such eyes, save in some famous picture of a world's hero or saint.

They were gray and deep. Deep? Oh, utterly, unfathomably deep; hundreds and thousands of years deep, yet Mr. Dual was certainly not an old man; and withal they were open eyes and frank. On the instant I felt subtly attracted to the man, and, hardly realizing the action, I put out my hand.

He took it in his and gave it a sturdy clasp, then released it, and waved me to a chair facing his own. "Sit down, Mr. Glace," said Semi Dual. "We shall have an interesting chat."

I took the indicated chair, and confess I felt a trifle confused. "Of course you know, Mr. Dual—" I began, when he took the words out of my mouth.

"That you are from the press?" he said, smiling. "Oh, yes; your card told me that. No doubt you were sent here to interview me. I have heard that the papers had interested themselves in the fact that I mind my own business. However, I was thinking of the man, rather than his occupation, when I spoke to you just now."

I laughed. "Frankly, I must admit that my reception has been out of the ordinary line of my experience. I half expected that the drink was doped when your man brought it out."

"Did you like it?" Dual inquired.

"I never tasted anything like it," I responded with enthusiasm. "If any bar or café could mix a concoction like that glass of ambrosia they would have to 'turn 'em away.' "

"It is a discovery of my own," Dual smiled back at me. "It cools, refreshes, and nourishes—all at the same time; also, it is a potent agent against the chief cause of human decay."

Here was an opening. "Are you, then, a chemist?" said I.

"Oh, dear, no!" my host objected. "What you drank was merely the natural juices of a variety of fruits, preserved after a method of my own. I have merely availed myself of a thing which every one could know if they would.

"But enough of that. No doubt you have some questions which you desire to ask me. Let us get that unpleasant part over, and then we can enjoy our chat. What shall it be? I believe the age and occupation generally preface most inquiries, do they not?"

I assented. "That, of course, Mr. Dual."

"Very well," said my most obliging acquaintance; "let us take up those first. As for my age, it is a thing I never think about, because it is of no importance to me; therefore, I do not see how it can reasonably concern any one else. As for my occupation, I may say that I am a psychological physician, I think."

I drew my note-book from my pocket. "A doctor of psychology?" I inquired.

Again Dual favored me with his smile. "You do not exactly comprehend my meaning," he replied, "though I admit a somewhat ambiguous nature in my remark. Let me explain.

"I live to help others in order that I may help myself. What a man soweth that shall he reap. If a man can distribute sympathy, comfort, happiness, he may receive the same if he shall ask it in return. If he gives health, he may be healthy. Do you see?

"It is my life-work to straighten some of the crooked turns of the life-paths of others. If I can but right one wrong and not create another, I have not lived in vain. If my course marks pleasant memories along life's path, I and those whom I have met upon the journey are the better for it.

"Therefore, I live in order that I may do good; that I may unravel some of the tangled skeins; that I may smooth out the way that some one's weary feet must tread."

While he spoke I sat and listened, even forgetting to make a note in my book. There was something compelling my complete attention in the soft rise and fall of the cadences of the man's voice, in the poise of his body, the expression of his face, in his entire personality, in fact.

As he ceased speaking I sighed, and came sharply back to the realization that I had drunk in every word. Knowing that I should make some comment, I yet sat silent, because I knew nothing fitting to say—until Semi Dual came to my relief. "Do you not see the difference?" said he.

"Faintly," I confessed; "but tell me, Mr. Dual, if your mission is to help others, why do you remove yourself so completely from their midst?"

"Meaning?" said Dual.

"This manner of dwelling which you possess—this taking of a roof for a home. I admit it is charming; the garden alone is wonderful.

"When I saw the staircase I almost fancied that I had accidentally rubbed a genii's lamp and got myself wafted to some enchanted palace, like the heroes in my 'Arabian Nights,' back home; and when I saw the garden I was sure. But all this is out of the way, more or less hard to reach. Thousands must pass by you who need help, but never know that it is in reach."

Dual nodded his head. "I see your point," he said; "but those who are worthy will receive. I do not care to meddle with the affairs of the idly curious. Only the sincerely interested appeal to me, or deserve my time. Those who are deserving shall seek, and to such a one what is a flight of stairs?

"That which is worth having is worth an effort to attain. One must climb to find peace. Besides, I have a seclusion here which I might not find on a floor of a crowded business structure such as this. Here I can be alone to pursue my studies as I will. The very air is pure. The first ray of sunshine, and the last, are mine. One who seeks to interfere in the destinies of souls must be able to meditate much alone."

"There is another thing which I would ask you," I said; "only that I fear to seem rather impertinent."

"Do not hesitate," urged Dual.

"Well, then, that warning, or caution, or whatever it is at the head of the stairs," I burst out. "When I saw it, I very nearly turned round and ran home. I don't just figure it out. If I hadn't known that Smithson was at the office, I really believe I would have turned back."

"Is Editor Smithson the master of your destiny?" said Dual.

"He's the master of my pay-check, which amounts to pretty much the same thing," said I.

Dual laughed. "And so you felt pretty much as one who was about to enter Pluto's realm, as described in the legends of old. Poor chap. Yet, why should you, my friend?"

"I didn't know whether my visit would be taken as friendly or not."

"Oh," said Dual, "I see. You are not always greeted cordially, I suppose. However, the motto on the plate need cause you no alarm."

He waved his hand toward one wall of the room. "You see, I have another of them here."

I followed his gesture, and my eyes fell upon a framed card upon the wall. I rose and went over to examine it more closely, for from where I sat I could read only the largest top line: "Noli Me Tangere," which I knew was Latin for "touch me not." Below this was written, in smaller type, a different version of the message of the plate by the stairs.

Beware all ye who would do me wrong, for the curse of an Almighty God shall rest upon ye. Misfortune will be thine, through all thy life, until the uttermost farthing of thy indebtedness shall be paid. Take heed and curb thy greed, lest it destroy thee.

It surely was a "touch me not." I turned toward Dual, and this time I did not hesitate to express my surprise. What meaning lay beneath those peculiar words, to which he had called my attention by the wave of his hand.

Nothing certain, nothing tangible, yet so full of a subtly veiled meaning that even I, hardened reporter of sensational doings, felt strangely shaken, and shuddered as I read. For somehow I seemed to feel that it was every word true.

Something of my horror and sudden repugnance appeared in my next words, as I resumed my seat. "You mean, then, that you always revenge yourself upon any one who harms you in any way? Is that compatible with the doctrine of help and kindness which you uttered a moment ago?"

"Merciful Heavens, no!" cried Dual, spreading his hands in a gesture of negation. "That warning there is a warning; it is no threat. I revenge myself? It is the last thing I would ever think of trying to do.

"But, Glace, even I cannot change the law. Therefore I seek merely to warn others who might bring about their own destruction by seeking mine. Me they cannot harm, for I will not permit it, my friend.

"To an enemy I present passive resistance, which is the strongest in the world; because, while ever retreating, it is ever present, yet can never be reached. I merely refuse to be wronged, and the evil desire, which would harm me, finding no place to rest, merely returns to the source which sent it forth, and destroys. It is not I who revenge. It is the law."

"What law?" I said vaguely, seeking to prevent myself from falling under the strange influence which his words seemed to possess.

"The law of retributive justice," said Dual. "Of impersonal justice, if you prefer; which measures to a man exactly according to his acts.

"The law which rules the entire universe, which grows the grass, which rears the birds; the law which everything obeys save only man, and which he, for all his vaunted superiority, is too blind to see. 'Whatsoever a man sows that shall he reap.' That is the law. In all your career, young man, don't ever try to beat the law, for so surely as you do that same law will beat you."

"It sounds like Mosaical doctrine," said I.

"Moses was a wise man, and knew much truth," said Dual. "He was destroyed by his own greed. Man grows overconfident with a little truth. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.

"I once knew two men, and the greed of one caused him to wrong the other. They both lost all they had. The one of greed suffered, but the other did not. Once a man wronged another who was ill. Shortly the well man fell ill and died. Once a man sought to take from another, and a thief took all he had."

"You speak in parables," I said.

Dual smiled. "The abstract doesn't appeal to you yet," said he. "Let me be more concrete. In the first instance, two men went into partnership. One had a certain number of animals, which were bound, in all natural ratio, to increase. He needed help.

"He offered another a partnership with a half-interest in the increase, in payment for his time and work. The increase exceeded what he had expected, and he sought to hold all over the stated number for his own. The entire herd sickened and died. The law was broken, and the law was avenged."

"Then," said I, strangely shaken, "you are a man so terrible that all who seek to injure you must suffer for the act."

"They suffer—not for, but by their act," said Dual in level tones. "It is cause and effect."

"From which I would gather," I resumed as he ceased speaking, "that any one may exercise this power which you possess."

"I possess?" Dual repeated. "I possess no power. I merely live in accord with universal law. Any one who does that need never fear. He may protect himself from all harm without lifting a hand.

"Not every one knows this; therefore I have sought to warn—to frighten, if need be—by appealing to the superstitious awe of the unknown which lurks in every uneducated mind, because I do not wish any one to suffer anything because of me."

His words surprised me, and I looked upon the man with a new interest. With no trouble he had apparently explained the paradox, as it seemed, to me, of what I had seen and heard. Instinctively I felt that he was sincere.

"I beg your pardon for the misunderstanding," I said as I rose.

Dual smiled. "Granted," said he. "One of my missions is to replace misunderstanding by knowledge. If I succeed in sowing one grain of understanding I am repaid."

"And," said I, "you make your living by giving advice?"

"I accept sometimes," said Dual. "I never ask. I am always willing to give to those whom I believe deserve."

"But you have to live," I insisted. "How then do you—"

"I take what I need," said Dual. "I care not for wealth. To me money is a servant; it is no master of mine. Should I lose what I have I should feel no remorse, for the wealth of the universe is at my disposal at need. Greed destroys—it can never build up."

I nodded. I confess I didn't believe. I thought of Saturday night and my paycheck. I knew what its loss would mean to Gordon Glace.

"Mr. Dual," I said, extending my hand, "these are queer theories to me, and interest me, I am free to confess. I shall see that they are fairly dealt with in the article which will appear in the Sunday Record—" And I stopped.

For the life of me I could get no further. A peculiar sensation started in the back of my brain, and, in spite of all my own volition, I found myself looking deep into the calm eyes of this most peculiar of men. Strangest of all, I found that I couldn't look anywhere else.

Presently I became conscious that he was speaking to me in a new manner: "You will do nothing of the sort, Mr. Glace. You will merely return to your editor, and tell him that you saw me, and that I forbade the interview's being put into print," Mr. Dual said.

"But I cannot do that," I cried in alarm. "Why, it would mean my job." I was strangely flustered—not at all myself. Under ordinary circumstances I would have given a gracious assent, gone my way, and—the interview would have appeared just the same.

But, somehow, Dual's words were not a request. They were a statement of fact, and for some reason in Dual's case I admit I feared to disobey.

At the same time I was filled with a sudden feeling, almost of anger, that any one could so control any act of mine. I opened my mouth for further protest, only to again feel the power of the man's eyes upon me.

"You will do nothing of the kind," he repeated, "and this interview, so far as your paper is concerned, will be as though it never was. If your editor should insist upon it, tell him that I said he should come here and read what is written at the entrance, and—meditate." He smiled full in my face.

My intellectual fog blew away before that smile. I felt relieved, and did not dread meeting Smithson at all. Contrary to my lifelong custom, I now resolved that I would not write an account of this interview; and yet, for the first time in my life, I was really afraid.

Almost in response as it seemed to my thought, Dual spoke again: "Thank you." And a moment after: "Fear not."

I rose. "I must be getting back," I said, and I seemed to speak in a dream. Again Dual smiled.

"Quite right," said he. "Even now Smithson is cursing because you are not there to go out on that murder case."

I started. "What's that?" I cried.

"Smithson wants you," said Dual. "It is important, so make haste." He touched a bell.

Once more the servant appeared. "Good day, Mr. Glace," said Dual, rising. "You will come to see me again shortly." He offered me his hand.

I took it, and followed the servant out. Once more I crossed the inlaid plate and heard the chime of bells.

Once more I traversed the staircase and found myself at the elevator-shaft. I hastened into the cage, and fretted and fumed at the slowness of the descent. Smithson wanted me; I wanted to reach the office, quick.

It never occurred to me to doubt the truth of the fact. It was only afterward that I wondered how Dual knew.

At the time I accepted the statement as fact, which shows how fully the personality of the man had impressed itself upon me.

I fairly ran out of the foyer of the Urania, and on up the street.

I entered the local room with a rush. Smithson popped out of his den like a jack out of a box, and greeted me with a howl. "Oh, there you are! Think I sent you on a vacation? Where you been?"

I started to explain, but Smithson cut me short. "Can that," he bawled. "Get up to 49 Jason Street just as quick as the Lord'll let you. There's a dead girl in a room up there. I caught a crossed-wire message fifteen minutes ago, and notified the police myself. Get out of here now, and for the love of Mike don't get lost!"

I started for the door on a run; but, even as I took the stairs three at a jump, my mind was busy with a thought, which, when it was fully developed, amounted simply to one short phrase: "Dual was right. He knew."

I FOUND 49 Jason Street to be one of those warrens of human dwelling, commonly known as "family hotels." In it you could rent anything from a single room to a complete suite and keep your servants, if you could still afford any, in special quarters next the roof.

It had a handsome entrance, a showy foyer picked out with much gilding and studded with numerous electric-lights, though these were not turned on when I entered the place.

I told the hall-man my errand, and he showed me to an elevator and ordered the boy to take me up to the room where the dead girl lay. The boy slammed shut the door and started the car, then turned to me with a grin.

"It's funny," said he, "how folks kin make a noise after dey're croaked. Dis here kid what's got hers never did nuthin' that I know of till now, an' now look at the fuss. I've took two bulls, three fly cops, and about six of you reporter fellows up to her room in de last fifteen minutes. Well, here you are."

He stopped the car and slid back the iron door. "Room ten," he directed; "straight down de hall to yer left. You kin hear de row when yer git there, I guess."

I made a note of the boy. He was loquacious and inclined to tell all he knew. I made up my mind that I would question him more presently; then turned and went quickly down the hall to room ten. The door was closed, and I rapped lightly.

Jimmy Dean, of the Dispatch, opened the door and let me in. "Hallo!" said he. "We were beginning to wonder if the Record was asleep."

"What is it?" I asked.

"Murder, I guess," said Dean; "at least, that's what the bulls seem to think. Anyway, it's a cinch the girl never choked herself to death."

I turned toward the group of officers and plain-clothes men beside the patent, disappearing bed on which the woman's body lay, and drew in as close as I could.

The victim of the apparent tragedy was a girl of perhaps twenty-three or four, to judge by her looks, which were striking even in death.

Her hair was brown, as were also her eyes, and her face was that peculiar reverse oval which one sometimes sees, with a rather narrow forehead and a general fullness of the cheeks and lower mandible, so that the face really appears broader below than above.

Just now her body lay upon its back, with the feet projecting over the edge of the bed; the eyes open and staring, the lips slightly gaping, and with some flecks of blood dried on the lower lip and the chin.

About the throat, where the neck of her dress was partly torn away, were the purple marks of fingers. There was no possible doubt that she had met death by strangulation; probably, from her expression, fighting to the very last.

Yet she had not been strangled upon the bed, for its coverings were totally undisturbed; nor was the room to any extent disarranged. Save for the collar of her dress, her clothing even was in perfect condition; evidently death had come upon her with the suddenness of an overwhelming force.

She wore a black silk waist and a brown serge skirt with a belt. Her stockings were of black gauze, and she still had a pair of low pump-shoes upon her feet.

The apartment showed evidence of a good, if somewhat fussy, taste. It consisted of a living-room, kitchenette, and bath. Later, examination of the latter showed nothing of interest, though the remnants of a meal on a small table in the kitchen showed that the girl had dined before she died.

In one corner of the living-room was a small writing-desk with the leaf of its top open, and while I was still looking at the body on the bed Dean went over and began to inspect this in an idle sort of way. Watching him out of a corner of my eye, I saw his half interest suddenly give place to hardly controlled excitement.

With his eyes on the group of officers gathered about the bed, he put out a hand and picked up a piece of paper, to which he gave a hurried scrutiny before thrusting it into a side-pocket of his coat. I made a mental note of his action, and in a moment slipped over to his side. "What did you find?" I said quickly, speaking too low to be heard by the others in the room.

Dean shot me a sharp glance, then shrugged. "Darn you, Glace!" said he, half laughing. "Did you see me pick that up?"

"I can tell you which pocket it's in," I replied.

"All right," Dean surrendered. "Go out in the kitchen and get a drink. When I hear the water running I'll get thirsty, too, and we'll have a look at the thing."

I nodded, turned, and walked out of the room, and presently turned on the water-tap in the kitchenette. A moment later Dean sauntered in, pulled the bit of paper out of his pocket, and we bent our heads over what was evidently a half-completed note:

Dear Reg:

Am expecting—you know whom to-night. He seems to be inclined to cut up a bit rusty, but I am almost done with him, I think. You see, I can do as I please, while things make it necessary for him to be careful what he does. When I get that five hundred thousand—be still, my heart, so much money makes me faint—well, when I get it, and it's got to come soon, why, we'll hike out for a nice little place I know of across the blue sea, and have our very own honeymoon—just you, boy dear, and I.

I hear the elevator stopping. I wonder if it is the old man. Hope it is. I expect to finish things with him for all time to-night. Gee, I will be glad when you and I can go away and be happy. Some one is rapping. More later.

But there was no more. There never would be any more from the hand which had penned those lines.

Dean and I glanced at each other, and he folded up the paper and put it away before either of us spoke.

"Dean," said I, "that is important; it's got to go to the police."

Dean stood for a moment, scowling; then nodded, and got the paper out. "Here," said he, "let's make a transcript of the thing. Then I'll pass it on: to the bulls. It may prove a clue for all we know. But— Oh, Lord, don't I wish we could keep it for ourselves!"

We took a copy of the half-completed message, and then sauntered back into the other room, where Dean approached the precinct sergeant and tendered the note.

Robinson grabbed it and glanced through it, then called the detectives to his side. "Where'd you get this?" he inquired of Dean.

"It was lying on the leaf of the writing-desk," said the Dispatch reporter, smiling. "I thought it might interest you, so I copied it, and then passed it along."

"Copied it, did you?" grunted Sergeant Robinson. "Yep; I bet on that."

"Yes," said Dean, smiling. "I thought it best. I could have kept it, you know."

Robinson nodded, without apparently paying any attention to what Dean said; then turned to his men with a grin. "I rather guess this here settles the thing," he said.

"This kid here was playin' fast and loose with a money guy, and has a lover on the string at the same time. Well, one or the other of the two men got wise and put her away. Just a plain, old-fashioned killin' outer jealousy it looks to me.

"What we got to do is to try and find out who the two fellers was that come here the most, and then watch 'em a bit. When th' coroner comes he kin take th' body. Johnson kin stay here an' watch the room. Th' rest of us kin git out now."

While he had been speaking I had gone over to look at the body more closely, and in the course of my examination I picked up the dead girl's hand. What made me do it were some stains of blood which I noticed on the fingers.

I raised it to scrutinize the spots more closely, and then I kept it for a reason which interested me far more. The woman had worn her nails long, and as I raised and turned the hand I distinctly saw something caught under the index nail.

At first it looked to me like a little roll of thin paper; but, as I gazed upon it, it suddenly came over me what it was. It was a small rolled-up bit of human skin.

I laid down the hand and examined the woman's throat for any sign of scratches. There were none. I looked at the other hand. It was intact. Then I picked up the right hand again.

I looked at the fingers severally in turn, and under the nails of the first three I found those funny little rolls of dirty white substance. A great elation woke inside of me. I saw as in a dream what had happened. I saw the struggle as it had been; the man choking the life slowly from the woman's body; the girl fighting in desperation, digging those long nails into his hand, seeking to break his grip, succeeding only in tearing those little bits of skin from the crushing hand. I laid the hand down gently, and got up and walked about the room. I was sure no one else had noticed it. I had a beat on the rest, in so far at least.

The others were preparing to leave; that is, the officers and all the detectives save that one to whom the case had been assigned, and the reporters who would hang about to see what the coroner might say. It was then that I had a flash of intuition which changed my entire fate.

In one corner of the room there stood a typewriter, and as my eye fell upon it I went over and, drawing out the drawer of the table upon which it stood, I rummaged about until I found a sheet of carbon paper such as is used by all operators of writing-machines in making duplicate copies of their work.

With this in hand I approached Robinson and preferred my request.

"One moment, sergeant," I said as he was lighting a cigar before going back to make his report. "That note now. Would you mind letting me make a carbon copy of it before you go?"

"What for?" snapped the officer. "Hain't you fellers all got a copy of it?"

"But I want to run a photograph of the original," I explained.

Robinson favored me with a grin. "My, but the Record is gettin' yellow these days," he said.

But he gave me the note, and after smoothing it out I laid it on the carbon paper, slipped a sheet of plain paper—also taken from the typewriter-drawer—beneath it, and, taking a blunt pencil, traced over the lines of the writing, while my fellow reporters stood and watched me; each, I suppose, kicking himself mentally that he hadn't thought of the thing.

When I was done I had a fair copy of the note and handed it back to the grinning Robinson, who stowed it away and went stamping out.

Dean alone of those who remained seemed to sense that there was more in the thing than appeared. Catching me at a moment when we were sitting a little apart from the rest, he leaned over and asked me what I had up my sleeve.

I shook my head. "I don't really know," I told him. "Some way I've got an idea this will be a pretty hard case for us to crack. Something told me to get a copy of the note. I'll run it in the paper, of course, but it may be handy in other ways. Just now I don't know how."

Dean sighed. "If only you and I were famous detecs, now," said he, "we could deduce this girl's whole character from that note. Some people claim that you can do that from the handwriting, you know."

I did know it, but it had slipped my mind. Now I began to wonder if it might not be true. I made up my mind that I'd be very careful with my copy of the note.

My meditations were interrupted by the sound of footsteps outside, and a moment later the coroner entered the room. At his request, we described the appearance of the room and body when we entered, and after viewing the body himself he sent for the manager and put some questions to him.

From the manager's answers it appeared that the girl was known as Miss Madeline More. She had lived in the hotel for upward of a year.

She had always seemed a very quiet and reserved sort of a young woman, and seldom had any visitors, save a young man of apparently twenty-eight or thirty, of above medium height, and light complexion, who sometimes came and took her out in the evenings; and a prominent attorney, who was in the habit of coming to her with special legal work, which she did for him. She had made her living, so far as the manager knew, by doing general stenographic work.

He professed ignorance of the young man's name, but stated promptly that the attorney was Ex-Judge Barstow—a man known prominently in legal circles all over the State.

"Come to think of it, the judge called to see her last night," said the manager; "so she must have been all right then."

"What time was that?" the coroner asked.

"I don't just know," said Manager Jepson. "I can call up the office; perhaps they would."

Inquiry developed that the judge had come in about eight, and left some time after, stopping at the stand in the foyer to purchase a cigar.

Further inquiry from the various tenants and the operative force elicited nothing. No one had heard any disturbance at any time during the previous night or during the day which was now rapidly deepening into dusk.

The floor chambermaid had gone to Miss More's room several times during the day, finding the door, which had a spring-lock, fastened each time. Finally, growing surprised, she had gone so far as to climb up and look over the door through the transom, whereupon she had seen the girl's body lying fully clothed upon the bed, and had given the alarm.

When the door was broken open things were as they now remained, with the exception of an open window which gave upon a fire-escape.

This the chambermaid distinctly asserted was open when she looked over the transom, because she had noticed the curtains blowing into the room.

So much we could learn, and no more. Even the elevator-boy couldn't say what time during the day before or the evening the woman had come to her room, because there had been a break in the mechanism of the cage, and from three until six every one entering the different apartments had to walk.

After six he was positive that she had not come in, so that she must have entered her room between three and six in the afternoon of the day before.

With such meager gleanings the coroner had needs to be satisfied, though he did not appear so at all. However, he finally ordered the body taken to the morgue, and called an inquest for two days later, in the afternoon.

With his permission, the detectives and several reporters then proceeded to ransack the flat, but we found little for our pains. Beyond some purely personal notes and some legal papers on the typewriter or in its drawers, there was nothing to indicate anything about the girl's manner of life. As for myself, I watched Bryson, the plain-clothes man, closely. I wanted to see if he would discover what lay beneath the fingernails of the girl's right hand. Apparently he did not.

The coroner then ordered us all from the room, the door into the hall stood open, and one and all we stepped into the passage, and it was then that I quite inadvertently dropped my fountain pen in the darkest corner I could find.

I got down on my hands and knees and began to grope after it, while the others walked slowly down the hall. In spite of my most persistent endeavors, I didn't find the thing until I saw them enter the cage. I was just picking it up, when Dean yelled back to know if I wasn't coming.

Actually he made me drop the thing again, and I told him to get along, and I'd be down when I found my pen.

All of which leads up to the fact that I wanted to see my elevator-boy alone. I got him, and told him to run up to the top and then come down again slow. What he saw in my hand made him anxious to comply.

"See here," I began, as soon as we had started, "do you know Judge Barstow by sight?"

"Sure," said the kid, grinning. "He used to come up to ten a lot."

"What for?"

"Huh!" said the boy slyly. "Say, what yer tryin' to get at?"

"I just want to know," I replied.

"You're a reporter, ain't you?" said the boy.

I nodded.

"If I told yer, would yer write me up in de paper?"

Here was vanity, if I ever saw it. Again I nodded my head.

"Well, then," said the boy. "He used to come up an' bring papers an' things for her to write. She punched a writin'-machine, yer know."

"Yes."

"Well, he comes here last night, a little after eight, an' after while he come back an' got inter the cage, sorter whistlin' to hisself. Just when we was stoppin' down below he gimme a quarter, an' told me to tell Miss More when she come in that he'd been here an' lef' some papers under the door."

"Done what?" I yelled.

"Pin stick yer?" quizzed my impudent informant, starting the cage down.

"What did he say he had done?"

"Lef' some papers, I said," replied the youngster, "an' he wanted me to tell her to be sure an' get them done for to-night, 'cause he would be back for 'em sure."

"Did you tell her?" I asked.

"That's de funny t'ing," said the boy. "Up to then I didn't know she'd gone out, an' I don't know when she come in. She muster walked, but sometimes she did do that."

"Were the papers found—the ones the judge left?"

"I dunno, mister— Hully gee! Thanks!" He stopped the car, and I got out.

"Say," I said, "don't tell this to any one else for at least a day."

"All right, I'm hep," said the kid, grinning.

I turned and walked away.

I didn't go far. What the boy had told me had excited all my sense of curiosity. I wanted to know what the papers were. The room was guarded by a policeman, however, and would be until the body was removed. After that, no doubt, it would be kept locked.

I scratched my head and thought. After a bit the answer seemed to be the fire-escape. That meant waiting till night; but first I walked around to the side of the building and made sure of just where the fire-escape came down.

Then I went back to the office and wrote my story of the affair, as far as I could go.

Smithson read it and grunted approval. He never mentioned the story about Semi Dual. To tell the truth, I had forgotten all about it myself at the time.

A grunt of approval from Smithson was the same as a laurel-wreath in times of old. It fired me with an intense desire to make good on the later phases of the case. That and my natural desire to get into the heart of the mystery both made me decide to get into the room that night.

I knew that it was but one chance in a thousand that the papers were there. We had all of us looked over the room. Even if they were there, they might not amount to anything at all. Still, I had thought of a possibility, which I wanted to prove or disprove.

I decided to get Dean. He and I frequently hunted in couples, and he was a fellow who would run fair. I called him up, and was lucky enough to find him still punching out copy. I invited him to a sandwich and something to drink, and met him half an hour later at a little rathskeller down the street.

There I unfolded to him my scheme for getting into the room and finding out if the papers were there. At first he was not at all enthusiastic, but after another drink he agreed to help me "make a fool of myself," as he predicted, and we got our hats and set out.

On the whole, the thing was easier than I had expected. Jimmy gave me a back up, and I managed to catch the lower round of the iron ladder on the fire-escape and hold on till I pulled myself up.

Then I took off my coat and let it down to him, and he managed to make it after a try or two. We sneaked up the ladder like a couple of thieves, and presently arrived at the window of what I knew ought to be the girl's room.

There we paused while I examined the sash and found that, though closed, it was not locked. It yielded easily to my efforts, and I soon had a way into the room.

"If there are any papers here—if Barstow really left any, he probably shoved them under the door," I explained again to Dean. "Maybe in shoving them under he got them under an edge of the carpet as well. Stay here; I'm going to find out."

"Go ahead," said Dean, seating himself on a rail of the escape. "Only, I'm in on what you get."

I slipped into the room. By the light which filtered through the transom of the hall-door I could see the lay of the place, and also that the body had been removed from the bed.

Walking on tiptoe, I hurried over to the door which gave into the hall, and got down upon my knees on the floor. And now I confess my heart beat fast.

It all depended upon whether the edge of the carpet in front of the door was loose or not.

My groping fingers found the edge and tried it in a tentative pull.

It gave!

I turned it back and thrust an eager hand beneath. My fingers touched a folded document, and, trembling now in every fiber with my eagerness, I drew out the paper, and, still searching beneath the turned-back carpet, convinced myself that I had found all which was there.

When I rose and swiftly regained the window, where I found Dean, for all his assumed skepticism, crouched, peering within. I shook the paper under his nose.

"There, you old skeptic," I whispered in jubilation, "for once you see you were a little bit off."

Dean whistled softly.

"Jumping fleas!" he exclaimed, helping me over the sill by the expedient of half pulling my arm off. "Did you find it, Glace?"

"It rather looks like it, doesn't it?" I chuckled. "Come on. Let's get back to the rathskeller, where we can see what the paper is."

We went down the fire-escape hand over hand, and dropped to the ground. Then we beat it up the street toward the rathskeller, where we had had our sandwiches and drinks some time before, and managed to get a table far back in a secluded corner of the room.

Then, and not till then, I drew the papers from the pocket of my coat and laid them on the table before Dean and myself. To all appearances they were merely some copies of depositions, but thrust under the rubber band which held them was a bit of paper containing a few lines written in a penciled scrawl:

Miss More:

Came up to see you, but was so unfortunate as to find you out. Hope to find you at home tomorrow. Will call for the papers. Please make four copies of each.

"What do you make of it?" said Dean.

"It appears to bear out the elevator-boy's story," I answered slowly. "What gets me is why a man of Barstow's position should take his work around to the girl himself."

"Uh-uh," agreed Dean. "Funny the papers weren't seen this afternoon."

"Well, as to that," I said, "I fancy that when Barstow shoved them under the door they went under the rug. When the body was discovered nobody thought of anything else for a time. Probably some one, coming through the door, struck them with a heel, and sent them clear under, out of sight."

"That might explain it," admitted Jimmy. "I wonder if Barstow's known the girl long? Tell you, Gordon, we ought to try and look up that girl's past. We might find something there. Let's go see Barstow, if you don't mind."

I nodded. We drained our glasses and left the café for the street.

JUDGE WILLIAM BARSTOW, ex-judge of the criminal bench, lived in a handsome residence, in the most fashionable part of the city.

There must have been at least four acres in the grounds, besides what was occupied by the house and garage. This was beautifully parked, and upon the whole was one of the show places of the town.

I confess I was rather loath, after we got started to call upon the judge at that hour of the night, but Dean urged me on. "Sometimes," said he, "a cold trail leads to a hot scent. He can't do more than have the butler buttle us out the door."

"All right," I assented. "All I ask is that you go first and take the first buttle for your own."

We dropped from the car at the corner and went up the winding walk to the front door. "Servants and solicitors at the rear," I reminded Jimmy. But he shrugged in high disdain. "Shut up," he told me, "and try to remember that you represent the majesty of the press."

Jimmy punched the bell rather viciously.

Then we stood and waited until the door was opened, and a very imposing functionary demanded the cause of our call. We gave him our cards and requested a few moments of the judge's time. After showing us into a reception room the servant departed to see whether we got it or not, and Jimmy heaved a sigh.

"He didn't seem impressed a bit," he complained. "I wish I'd worn my other tie."

"The one you have on will be enough to hang all our chances," I told him.

He was just about to make some sort of an answer when the butler returned and informed us that the judge would be down in a moment, and desired us to wait.

Although it was ten o'clock when the judge came down, he was dressed for the street, even to a top hat, light evening coat, and gloves. He came across toward where we had risen, with an extended hand, and greeted us smiling.

"You will pardon me, gentlemen," he said, "but I have just been called to a client of mine, and can give you but a few moments to-night. Still, as I am going to cross the business section, you can ride along in the motor, and we can talk on the way."

"What we want to learn will take but a moment, Judge Barstow," said Dean. "You no doubt saw the account of the death of a Miss More in the evening papers. It would be in the late editions, I suppose, though I didn't see one myself.

"We want to know just what you knew about the girl. So far we have been unable to find out anything about her at all, save that she was a professional stenographer."

"Yes, yes," said the judge. "I didn't see the papers, but I had heard of the affair. You see, a reporter was here earlier in the evening. I can, however, tell you but little of interest, I fear.

"She was at one time employed in my office, but later left it because she thought she could do better by doing piece-work. She was a very efficient typist indeed. Although she was no longer with me, I sometimes took or sent work to her when I wanted it done with particular care. But no doubt my car is waiting. May I give you a lift down-town?"

We accepted the invitation, and after we had taken seats in the judge's limousine Dean again renewed his search for facts.

"Did you call to see her last night, Judge Barstow?" he asked.

"I did," said Barstow. "Come to think of it, I left some papers under the door, with a note asking her to get them ready to-night. I meant to call for them, but was out of town all day, and the thing had slipped my mind. She was out at the time I called, and I asked the elevator operator to call her attention to the fact that they were thrust under the door."

"Did you often leave important papers lying around like that?" said Dean. "Are you in the habit of doing so?"

In the light of the street lamps we could see Barstow silently laugh. "No, Mr. Dean," he chuckled, "I am not. But it was safe to do so with Miss More. Her training in my office, together with her natural intelligence, made her sure to comprehend what I needed. Your point was well taken, however, I must admit."

"What do you know about the girl's antecedents?" I inquired.

"Not a thing," said Judge Barstow. "She always seemed quiet and well-behaved. If I remember rightly, she once told me that she was an orphan."

"Did you know that she expected to fall heir to some money?" I hazarded, thinking it likely that he would be asked to look after her affairs if she really expected to get such a sum as she had mentioned in the note Dean had found.

"I did not," said Barstow, and I fancied he frowned.

"Well, she was engaged, wasn't she?" said Dean.

"She had a young man," said the judge, as he offered us each a cigar from a case and lit one himself. "He was a chap of about twenty-eight, I should say. Whether they expected to marry or not Miss More never said."

"Did she ever tell you his name?" said Dean.

Barstow nodded. "I met him once or twice," he replied. "Watson, I think the name was."

The auto swerved and slid in toward the curb in front of the office of the Dispatch. Dean and I got out, and Barstow shook us each by the hand.

"Sorry," said he, "that I couldn't help you boys more at this time, but if there is anything I can do in the future, don't hesitate to call upon me." The door of the limousine closed on the last word and the machine got under way.

I turned to Dean. "Your cold trail is pretty well frozen up," I said. "I'm going to the office, and then to bed."

"I don't know. At least we got the fellow's name," said Jimmy. "Come and walk down the block. Barstow's office is in the Kernan Building, and while you have been babbling an auto stopped down there. It may be his car, and it may not—I'm for finding out."

We walked along slowly, and stopped just short of the office building, before which stood a motor with its engine throttled down. Jimmy pointed to the number and grinned. "It's he, all right," he announced. "I thought he said he had a client to see."

"Maybe he had to get some papers," I suggested.

Dean merely nodded and stepped back into the shadow of the building wall. "Anyway, I'm going to wait till he comes out," he announced.

Of course I stayed along.

Five and ten minutes passed, and then Judge Barstow hurried from the Kernan entrance, entered the car, and rode off. But as he entered the machine he spoke to the driver, and both Jimmy and I distinctly caught the one word "Home!"

I looked at Dean, and he upon his part looked at me. Finally: "Was the alleged client a plant?" he muttered. "Did he really just want to give us the shake?" Then he grinned. "Oh, I don't know about this trail being so cold, after all, Glace, old chap."

I confess I was puzzled. It had been a trying day. I shook a sadly topsy-turvy head at my friend Dean. "Suppose we try the police station and see what they have done. The more I see of this thing, the more muddled and interested I get."

Dean locked his arm in mine and we set out, walking for the most part in silence, each busy with his own thoughts, until such time as the green lights of the station threw a ghastly light across the sidewalk, and we turned into its door.

It was a night of surprises; first the papers under the rug, then Judge Barstow's peculiar conduct, and now another which awaited us in the precincts of constituted law. At out first inquiry the sergeant laughed. "Hain't you heard?" he asked.

"Heard what?" we chorused in reply.

"Why, they've pinched the girl's sweetheart. Looks like they've got him with the goods on, too."

Here was news indeed. Dean reached into his pocket and drew out a couple of cigars, which he solemnly laid on the sergeant's desk.

"Here," said he. "I was going to smoke them myself, but I guess they belong to you. We've been taking a Rip Van Winkle, Glace and I. Suppose you wind us up and give us the right time."

"Nothin' to it," said the sergeant, biting on one of the brown rolls. "This afternoon after everybody had left the hotel, a young feller answerin' to the description of the girl's man comes into the hotel and gets on the elevator and gets off at five. The elevator kid is wise to him, havin' took him to the girl's rooms more than once, an' he beats it down an' puts the office wise.

"In the mean time th' feller goes to the girl's room an' runs into our man, who was still waitin' for the dead-wagon from the morgue. He seems surprised an' asks what's wrong. Of course Johnson laughs in his face, an' the guy gets kinder fresh. Just then th' manager comes up an' tips Johnson off, an' he starts to make a pinch.

"Well, the feller tried to put up a fight, an' Johnson had to club him 'fore he'd be good. They brings him in, and when we searches him we finds a lady's watch, with the girl's name engraved in it, in the fob pocket of his pants, an' also a swell diamond ring that fit the third finger of her left hand. It sure looked good to us, so we sent him back. Pretty quick work that, eh?"

"If you've got the right man, it's chain lightning," said Dean.

"If?" said the sergeant. "Say, what yer want to talk like that for, Dean?"

"Well, what did the fellow say?" Jimmy asked.

" 'Bout the usual thing," the officer growled. "Told a fairy story 'bout havin' broke his watch, an' the girl's lettin' him have hers to wear. Said the ring was one that had been his mother's what he was goin' to give the girl for a engagement ring. Claimed he didn't know she was dead."

"Well, if he did, why did he go up there?" I asked.

"He didn't say," said the sergeant with a grin.

"Had the ring been altered in size?"

"I don't know that either. I didn't look to see."

"If it had been we could probably trace the job and verify his statement if true?"

The sergeant nodded and got up. "I put 'em away in the safe, after we tuk 'em offen' the guy," he explained as he crossed the railed-in space back of which he sat. "Suppose we have a look at 'em now."

For a moment he busied himself with the safe, running methodically through the combination, with counting and pauses between each turn.

Presently, when the door swung open, he found the property taken from the recently arrested individual, and returned to his desk with the watch and the ring.

It was the latter which claimed our first attention. Dean and I went over and stood beside the desk, and together the three of us examined the thing. Nowhere in all its circumference was there any sign of a cut or a mend, in fact of any sort of work at all. To all appearances it was now as it was when originally made.

"It looks bad," said Dean. "Of course it is possible that the girl wore the same size ring as his mother, but it seems hardly likely to me." He picked up the watch.

It was a lady's ordinary chatelaine case of gold, contained a Waltham movement, and was engraved on the inner side of the case with the girl's name, and a date. Apparently it might have been a present to her at some time.

"What do you think?" said Dean as he laid it down.

"It looks like a real pinch," I was forced to admit.

The sergeant cocked Jimmy's cigar in a corner of his mouth and hooked his thumbs into his vest. Presently he blew out a great cloud of smoke, rose and gathered up the trinkets, preparatory to putting them away. Then he began to chuckle. "It's a sure enough pinch," he said.

"What was the chap's name?" I bethought me to ask.

"Wasson," said the now smiling sergeant. "Reginald Wasson for short."

I glanced at the clock. It was almost twelve. I rose and rolled a cigarette. "Come On, Jimmy," I said, "we've got a lot of writing to do. Good night, sergeant, there was sure some class to that work."

"Wasson—Watson," muttered Dean when we were outside. "Well, I guess Barstow meant to give it to us straight. The names sure are something alike. I wonder if they've really got the right man. What do you think?"

"I think I'm going down and write some sort of a story and get to bed," said I. "Only you can bet yourself a dinner I'd hate to be in Reggie Wasson's shoes."

Well, I did go to bed when my work was finished, but I didn't go to sleep. The events of the day kept buzzing like pinwheels in my brain.

It had been a most unusual day. First was my visit to the peculiar individual who dwelt on the Urania's roof, with all its unexpected circumstances, climaxing in the character of the man himself. That had been like a page torn bodily from some old romance. If written, half those who read it would hardly believe.

Men didn't build grand staircases to a roof-garden, unless for profit, nor inlay plates of mystical warnings, set over a mechanism for ringing soft-toned bells, from purely altruistic motives nowadays. Almost I began to wonder if I had seen it myself.

Then my mind switched to the later events, which Dual had partly foretold. How did he know? The girl had been handsome in her way. Who had killed her, and why? Where was she going to get so much money?

Wasson was arrested. Was he guilty? If not, how had he got hold of the watch and ring? Might his explanation be true?

I tossed, and fretted, and turned. It was hot. I had a vision of a long crystal glass with ice floating in it, full of a peculiar, limpid liquid, and all at once I was consumed with thirst. What was it Dual had said to me? "I will see you soon," or something like that. Well, why not. I wanted to see him. I wanted to drink again of that beverage which he alone possessed. I wanted to talk over this case with the peculiar man who had first told me that there was a case.

I rolled over and berated myself for an imbecile, but the idea wouldn't down. It was too hot to sleep.

I made up my mind I would walk down to the Urania and look up at the tower. I even thought that if there was a light I might go up and see if Dual was awake. Somehow I felt that he was the sort of person who might at times turn night into day.

I kicked off the hot sheet and began to dress, actually hurrying into my clothes, like one in a great haste. After a bit I went out and stole softly down-stairs. 'Way over in the east there was a faintly grayer line in the darkness, and the air felt cooler outside.

I took a great breath of it into my lungs and started away toward where the Urania raised itself toward the still dark central sky. An early milk-cart rattled by. A newspaper-wagon trundled toward a morning train. Night owls were slinking home.

It was that peculiar hour between darkness and dawn, when the night is dead and the day is not yet awake, and things take on an almost mysterious air. I remember that some sparrows twittered in a tree as I passed, and I thought whimsically of how cold they were going to be six months from now.

After a while I came to the darkened entrance of the Urania, and though I had not seen any light from below as I approached, I turned in as though led by some compiling force, and groaning in very spirit, began to mount the stairs. Up, and up, and up. After a bit I lost count and simply kept on until I should see the great staircase. Then I would know I was at the top.

After an hour of seeming climbing it appeared, and I went up it, and across the glass inlay of the plate. Far off I heard the mellow bells, and as I reached the door of the tower it swung inward silently, before I could lift a hand to knock or even look for a bell. The servant of the afternoon stood before me rubbing a sleepy eye. Without waiting for me to speak, he led me to an adjoining apartment, and pointed to a stair.

"The master awaits you," he said.

I began climbing again, and after a time I came out into a broad room, which seemingly took in the entire top of the tower. Its sides seemed to be mainly of glass, so that one could look directly out into the night, giving one a temporary sensation as of floating in space.

A dim light burned at the head of the stairs, and by its feeble rays and the beginning dawn outside, I could see various instruments of an apparently scientific nature, arranged about the room.

At first I did not see Dual, but as I advanced a step he turned from a telescope, which was pointed out of an opened portion of the glass casings, and addressed me by name. "Mr. Gordon Glace," said he, "you are a fairly hard individual to call."

"I AM hard—to call?" I stammered.

"Certainly," said Semi Dual. "I desired to see you, so I sent for you. Why else have you come?"

"I couldn't sleep, and I was thirsty. I wanted a drink of that stuff of this afternoon. If you sent for me, I must have missed your messenger, Mr. Dual."

Again Semi Dual smiled dryly. "I hardly fancy you would evade, miss, or escape from my messenger," he said. "But you say you are thirsty: then let us go below."

"But I am disturbing you," I began. Now that I was here I felt like a fool. What sort of boy's trick had I been guilty of to thus break in on a man at peep of day?

"Not at all," protested Dual. "It is growing too light for me to work to the best advantage; besides, you are the next on the program. That was why I sent for you. I rather think I have found what I sought."

"Of course, you were studying the stars," I said. "One might think you a wise man of old, finding you like this."

"I was looking for a bad man of today, however," replied Dual.

"Looking for a man? In the stars? I thought the only man in the heavens was in the moon, and it's in the dark now."

"And yet," said Dual, smiling, "I found my man in the stars."

"Good Heavens!" I cried on the instant, as an idea burst in my brain. "Are you, then, an astrologer? I didn't suppose any one believed in that now."

"I believe in anything which is capable of a scientific demonstration, Mr. Glace," Dual said, as I thought somewhat coldly. "Suppose we go below."

He motioned me toward the stairway, and immediately followed me down.

We went directly into the chamber in which Semi Dual had entertained me that afternoon. He offered me a chair, then, excusing himself, passed through a door on the farther side of the apartment, saying he would return in a moment or two.

Left alone, I looked about the room, with a new interest in its furnishings, as the abode of the man who had met my morning intrusion with the air of something expected, and had even alleged that he had called me to him, at an hour when most persons might have been well in bed.

It was plainly, yet well furnished, carrying on the quality of quiet richness which I had noticed in the anteroom the afternoon before. Among other things I noticed what seemed to be a modified form of wireless receiving and sending apparatus. Also, there were several immense charts, seemingly of an astronomical nature, affixed to the wall.

A beautiful bronze female figure of life size stood at the side of his desk, holding an immense golden globe in her hand, from which poured forth a soft, mellow light. Casting back into my mythological education, I sensed it for a representation of Venus and her famous prize apple. As a work of art, it was superb.

Another thing which riveted my attention was a tall clock with a peculiar dial, showing the changes of seasons and months, the phases of the moon, days of the week, and months, and all sorts of things, as it appeared to me, besides the hours themselves. Truly, I began to feel that I was in the house of a most remarkable man; and then the door opened and the man himself appeared.

He was carrying a tray containing a couple of glasses and a small plate of cakes. These he deposited upon the desk, handed me a glass and a cake, and took the other glass himself.

"I will join you," he said, smiling. "After my night's work, I feel that it will do me good."

I lifted my glass and drank.

Again I experienced all the delight of the previous afternoon. I nibbled my cake; and I bethought me to apologize for my impulsive remark.

"Mr. Dual," I said, "I did not mean anything offensive when I questioned astrology a few moments ago; but I have always been led to think it a part of the superstitions of the Middle Ages. If I am wrong, I hope you will accept the statement as explaining my attitude."

Dual nodded, and set down an empty glass, wiping his lips.

"There were wise men in the Middle Ages, Mr. Glace," he began. "In fact, every age has had its percentage of those who knew the truth, and—the common mass. Sometimes they persecuted them, sometimes they crucified them, sometimes they burned them, sometimes—the exception, they listened to them—or at least a few did.

"I remember one instance, though it wasn't in the Middle Ages, when, had a noted man taken the warnings of an astrologer, he might have gone down to history as a benefactor, instead of a monster in human form."

"Then," said I, "am I right in supposing that astrology is an exact science, Mr. Dual?"

"One of the most exact in existence," my host replied. "It is in reality the earliest form of astronomy. If it were not a scientific fact, I would not care to waste time upon it. But I have proven it true; and right here let me give you some advice. Never accept anything for the truth unless it can be proven true, Mr. Glace; half the wars and sufferings of this world have come from unreasoning belief in fallacious facts."

"I wish you'd explain," I said.

Dual smiled. "An immediate application of my advice, eh?" he quizzed. "Very well, though I must be brief, as you have much more important things to attend to to-day. See here."

He rose and went over to one of the charts, picked up a long-bladed paper-cutter from the desk as he left his chair, and used it as a pointer for the chart. "Let me first ask you an elementary question of the common schools, Mr. Glace: 'What causes the rise, and fall of the tides?' " I felt his eyes upon me, and answered on the instant: "The moon."

"Quite right," said Dual. "Now, the moon is but an insignificant satellite of the earth, yet her magnetic influence affects the surface of the earth.

"The earth, in turn, is but one of a given number of planets revolving in the solar system of their sun. Each planet has a certain magnetic quality, which it radiates and which may be learned by observation. All these magnetic influences affect the earth, and are affected by the earth's own quality in turn.

"Now, if the moon admittedly affects the rise and fall of our tides—there was a foundation, in fact, for the superstition about planting seeds in certain phases of the moon, you see—why should we deny the effect of the other magnetic influences of the other planets equally upon the earth? There is no logical reason at all.

"Therefore, the fact of that influence remains. Given a certain part of the earth's surface, and a certain time, and a knowledge of the positions of the other planets, and what their individual quality is, and we can predicate the mean total of planetary magnetism operating on that point at that time."

His words impressed me, though against all my former training.

"It sounds plausible," I conceded as he paused.

"It is more than that; it is fact," smiled Dual. "Some day I shall prove it to you, Glace, but not now." He threw down the paper-knife and resumed his chair.

But I continued yet a moment with my questions.

"Then, with a given knowledge of the orbits of the planets, you could go farther, and predicate the influence at a certain point for a future time?" I inquired.

"Exactly," said Dual.

"Does the influence apply to human beings as well?"

"It does."

"Hence the soothsayers, Mr. Dual?"

"Rather the mathematical prognosticators, at whom ignorance scoffs," Dual replied.

"A rather nasty slap on the knuckles," I laughed. "What did you mean by saying you had sent for me?"

"The literal fact," Dual answered. "I did."

"Why?"

"I wanted to verify my own information by finding out what you had learned of the death of the woman in the Jason Street hotel."

Again I inquired: "Why?"

"Because," said Dual seriously, "I desire to see justice done. Not but what it would be in time, of course, but at times we may even rule Fate. Because I wanted to know if the suspicions of the authorities rests upon the right man; also, to prevent an injustice from being done."

"You talk as though you knew the guilty man!" I exclaimed.

"I know his general description," Dual responded. "I learned that to-night before you came. I need your assistance in finding him out; therefore, I called you, and you are here; now tell me what you know."

That was what I had come for. True, I had been distracted by the things which had occurred; but now, on the man's word, I was consumed with an eagerness to unburden my perplexed mind, and see if he could find any way out of the tangle of facts.

I began at the beginning, and went over all that had occurred. Now and then he interrupted with a terse question. For the most part, he sat with eyes closed, lying back in his chair, so that, save for an occasional slight quivering of his drooping lids, I might have fancied that he slept.

I ran over the finding of the body, the later conversation with the elevator operator at the hotel, the return to the room, and the finding of the papers and the note, the visit to Judge Barstow and his apparent attempt at evasion of any lengthy interview on the subject, what he had told us of the woman's history, the arrest of Wasson, and finally even my own peculiar sensations which terminated in my present visit to his rooms.

When I had quite finished, Semi Dual opened his eyes and sat forward in his chair. "Have you those notes with you?" he asked in a suddenly eager way.

"I have the genuine note which was on the papers under the carpet," I responded. "Of the girl's note I have only the carbon which I made."

"May I see them?" said Dual, extending his hand.

I got them out and passed them across to him, and turning his chair to the desk he quickly smoothed them out upon his blotter and began to pore over them intently, with an ever-growing interest.

"Dean said one might gain an idea of the writer's character from a sample of the handwriting—" I began speaking; but paused as I saw that my host was oblivious not only to my words but to my presence as well.

He had taken up a powerful lens and was going over the written lines word by word. Now and then he made a notation on a bit of paper lying upon his desk, and returned again to his study of the writing, each time more intent than before. The light of day was beginning to stream into the room, but the electrics over our heads still blazed on without his paying heed.

Far down below us I could hear the noises of the awakening world; the faint, faraway cries of newsboys, and the clang of the gongs of cars. But nothing disturbed in any way the concentration of the man at the desk. Presently, however, he made a last note, rose and turned off the lights, and came smiling back to his chair. "Mr. Glace, you are a most valuable assistant," he said.

"You find something of interest?" I inquired.

"Together we have found everything but the man's name," said Semi Dual.

"You mean you know his general description?" I cried.

"Precisely."

"But you can't. You say you don't know him. Then—"

"Why not?" interrupted my host, with his quiet smile.

"Well how could you—" I began.

"Mr. Glace," said Dual, "at the risk of appearing trite, I shall quote from my friend Shakespeare: 'There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in thy philosophy—Gordon.'

"My ability to describe this man without having seen him, happens to be a small part of the same. Besides, you have furnished me a very valuable aid by your clever work in getting this specimen of his handwriting, you see. I told you I had gone well forward in tracing him before you came up here. Even at that time I knew his physical characteristics.

"Now, from the writing I may say I am fairly well acquainted with his mental qualities as well. Glace, the murderer did not intend to kill until his hands were actually about the woman's throat."