RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

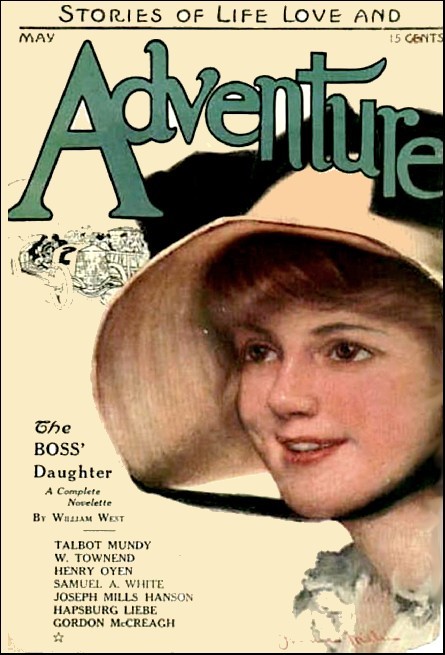

Adventure, May 1915, with "The Man From Home"

JIM HOLLY, known more extensively by the contraction of "Holy," because he wasn't, and because his most favored expletives were consecrated by that prefix, sat on a microscopic chair, just outside the flap of a little tent, before a diminutive table, and frowned at nothing. The chair was an X-pattern folder with a green canvas seat and back; the table was to match, with a green canvas cover on willow slats, which rolled up into a beautifully compact little bundle for transportation, and when in use rolled out flat—more or less; otherwise the X people make the best and strongest and lightest camp furniture in the world, although they are located in Boston.

The tent was of green Willesden canvas—which is as waterproof as rubber and many times as lasting;—and came from England. And all around, so close that the thoughtfully scowling young man could have touched it by stretching out his hand, was the greenest of thick green jungle. Altogether, the little camp blended so cunningly with its surroundings that an undesirable stranger—a forest-ranger for instance—would have had to pass very close indeed to find it. Against the green table-edge, close at hand, rested a 303 Mannlicher-Schönauer rifle, and over a tree-limb hung a Canadian N.W.M.P. saddle.

It will be seen that this stockily built camper, with reckless good humor showing through his perplexed frown, was a strict utilitarian and chose his impedimenta with a keen eye to efficiency, quite apart from the dictates of patriotism. Practical, swift efficiency; that was the key-note of the whole camp.

The man sat so still in his intent absorption that a green parrot climbed like a sailor hand over hand down a flaming bougainvillea creeper and croaked at him in raucous curiosity.

The steam and the stink and the appalling stuffiness of the hot weather had just passed, and it was the beginning of the cold season in the Terai foot-hills of Upper India, the glorious, cloudless, perfect respite of three months granted by a merciful Creator before all the plagues of Egypt—which have their ancient breeding-place in India—infest the land again. Yet Holy Holly frowned and twisted up his eyebrows and scowled at no apparent cause.

Suddenly the parrot cocked its head in alert suspicion at a far-away leathery squeak and a faint metallic click. Holly's practised ear told him that some clumsy person had blundered on to a half-dry teak leaf, and, in his anxiety to recover, had knocked his rifle barrel against a bamboo stem. He grinned widely in genuine amusement; and then, seemingly awakened by the diversion, reached out one hand and groped behind the tent flap.

With a quick sinewy effort of wrist and arm, he swung a pack-saddle trunk on to the table, which groaned beneath its weight. He opened it lazily and took from it the cause of his worriment—a letter. He spread it out on the table before him, and once again his forehead corrugated in contemplative indecision.

It was a long letter, of six closely written pages, signed, "Your old Dad"; and the alpha and omega of it was, "Why don't you come home, son; for a while at least? You've wandered long enough."

Once again there came a distant snapping of twigs and a faint exclamation, and the introspective frown shaded into one of annoyance—and then cleared up into a happy smile with the coming of final decision; and the young man took paper and wrote many pages of caustic observation and amusing comment. He concluded the letter with:

Guess you're right, Dad. The hunting game is about played out here. The game regulations are shutting down, something fierce; only so they can be relaxed under "special" permits in favor of titled visitors and people with official pull. Home sounds good to me, and I'll be along some time this Winter. I don't know how as yet, 'cause I'm broke just now; but I'll surely come.

It was characteristic of the man; and his old dad, who knew his son so well, laid down the letter with a happy smile and the certain knowledge that some day the wanderer would blow in all unannounced and calm as if he had just returned from a visit to the country.

CRANDALL, the sorely harried director of the Motioscope traveling company, sat in the dak-bungalow at Siliguri and ate up a considerable section of blue pencil, while he cursed all general managers and presidents with a far-embracing comprehensiveness and picturesque idiom that revealed the artist in the man. The cause of his frenzy was also a letter.

The company—just a small selection of "leads"—was touring the Far East, from Egypt to Japan, to make something new in pictures with local settings and real native actors; and he had just arranged a dramatic set of scenarios on Hindoo mythology and legendary lore, imminently satisfactory to himself, when there had come a mandate from headquarters which upset all his carefully laid plans.

The General Manager wrote to say that the tendency in the United States was now all toward making pictures of the dramatized versions of the works of popular fiction writers; and that the Motioscope Syndicate had just purchased the rights from the author—at a remarkably low figure in consideration of the difficulty of the undertaking—and he, Crandall, was forthwith to make pictures of Kipling's "Mowgli" stories. No expense was to be spared; but he must turn out sensational pictures, which would be sure to be a big hit, as nothing of the kind had been attempted before.

The director ate up some more pencil and gasped.

"Jungle Book stories!" he groaned. "How the Helen Blazes? Gosh, I'll need a traveling menagerie. Have they gone clear off sprocket over there?" And he sent for Herman, his camera-man, to condole with him, and perchance furnish a gleam of inspiration.

Herman listened with bewildered sympathy. He was helpful as a rule but this thing was beyond him; he did not even try to tackle it.

"Take the pictures?" he growled. "Sure I can take the pictures. I'll turn my crank on anything you stage, and guarantee good film; but you're the doctor."

He grinned cheerfully. Here was one trouble that did not affect his already over-harassed life.

"What does that Muckerji Babu man say?"

Muckerji was a semi-educated Bengali, that is to say, a Babu, and typical of the breed. The hopelessly groping film-producers, strangers in a strange land, had been misguided into hiring him as a "conductor," on the futile reasoning that an educated native should surely know more about his own country than any white man. But in the East things are not as in other lands. This Muckerji was a timorous creature with an appalling vocabulary, who judged the value of words solely by their length, and flooded his employers with a grandiloquent eloquence of hastily acquired and imperfectly assimilated knowledge on matters of historic and legendary interest.

But when called upon to aid in the present circumstances he was at sea. Being a Bengali, he peopled the forests with a wild assortment of devils, and bhooths, and mythical beasts; and being a Babu, he naturally knew less about the jungles and their ways than the newest subaltern out from England—and he knows, God wot, little enough.

"Sir-r," he said, "this theeng is too much diffeecult. It is undertaking of gigantic magnitude. However, by difficultly acquired college education—I am failed M.A., Sir-r—I can elucidate with application of mentality "

Crandall shut his ears and held them tight till the puffy, pan-stained lips ceased to move.

"Cut out the prologue, Babu, and flash just your leaders. Can you suggest anything? Now, right here; without taking a week to find out?"

The Babu's oratory sobered down; here was an argot more mystifying than his own.

"Sir-r, there is only one theeng," he confessed. "In this matter of jungles and ferocious beasts there is only one man who can advise, and that is Melvin, of Forest Department. Headquarters are at Mehter-Busti, B.N.W. Railway."

An older resident would have corrected him with, "Mister Melvin, you swine;" but Crandall knew no better, and accordingly to Mehter-Busti he repaired in his crying need.

MELVIN was a typical "official," strenuously devoted to duty, and therefore hidebound by precedent, and double-bound by red tape; but not a bad fellow according to the standards of his kind and creed. He fed Crandall and whisky-pegged him to profusion; but formally regretted his inability to help him.

"You can use the whole of this forest," he compensated, "and do whatever you like in it—provided, of course, that you don't overtread the usual Government regulation about violating local religious beliefs—but really, I don't see how I can help you to stage a circus; it's not in my line, you know. I shall be pleased to give you any information I can from time to time, but you'll have to wait a few days, for I have to rush off to Jagshahi to shoot an old rogue elephant who's been trampling on some of my people—one of the pleasant duties," he added with an explanatory smile.

"It's not often a fellow gets a chance of shooting an elephant, since they're protected by Government under a heavy penalty, unless they go rogue. I'm sorry I can't do more for you, Mr.-er-Crandall. Except perhaps—yes, you'd better base your operations from the dak-bungalow at Kalapani; nobody ever goes there, and you won't be disturbed."

Melvin was acting very generously according to his lights, and to a stranger withal; and Crandall thanked him warmly, but with despair in his heart, and accepted, as a stimulant, his invitation to stay to tiffin before starting on his long journey back.

Over the cigars Melvin volunteered, by way of making conversation:

"There's one man who could help you, Mr. Crandall, and that's Jim Holly—Holy Holly, as they call him. He has more uncanny knowledge about jungles and animals than any man I know, and he could tell you anything you wanted to know—if you could only get him."

"Where is this Holly?" demanded Crandall eagerly. "I'll surely get him."

"I wish I knew," said Melvin mournfully. "And you surely will not get him. I've been looking for him for weeks myself. He's somewhere in my forest; and I have him pretty well hemmed in, but I might as well try to catch a flying-squirrel."

"What d'you want the poor devil so badly for?" inquired Crandall, his sympathies already aroused in favor of the one man who could possibly help him.

"Well, it's my unpleasant duty to apprehend him and send him up before the Commissioner," admitted Melvin regretfully. "I hate to have to do it, because he's quite a friend of mine during truce intervals; but he's one of those turbulent spirits who positively refuses to recognize game regulations unless they fall in with his views of justice. He's a fine sportsman and keeps the close or natural breeding seasons strictly; but anything else—"

The accompanying gesture was indicative of despair.

Crandall's American ideas of liberty did not readily lend themselves to a conjecture on any other conceivable restrictions.

"What other regulations are there?" he asked, mystified.

"Well, in this particular instance," replied Melvin, "we're expecting a visit from Count Von Ziegenbock, and the order has gone out from the Lieutenant Governor that there's to be no shooting of big game in this forest at all, so that he can have a fresh field. Whatever my own opinion of the orders may be, it is my duty to enforce them."

Here was the stern, incorruptible British official who made a display of his integrity.

"This Holly, of course, came over and made formal declaration of war; after which he coolly borrowed a box of cartridges. And he's been devastating the country-side ever since."

"And I'm darned if I blame him!" exploded Crandall hotly; but Melvin only smiled and maintained inexorably that it was his duty to get him.

"I've got all possible exits pretty carefully watched," he insisted. "And he can't get away."

Crandall entered upon a warm defense of this lone champion who defied an autocracy; but Melvin merely shrugged his shoulders non-committally; and Crandall wended his way back to his little flock, invoking with one of his best flights the vengeance of all the bhooths in all the jungles upon the demented and ignorant rulers at home who so lightly set him to produce such an impossible set of pictures, thinking apparently that his mere presence in India was quite sufficient.

However, he had become director of the traveling company through an enviable reputation of being a man who could accomplish things, and it was up to him; and he cursed soulfully again at the thought.

A FEW days later Crandall, and Herman the camera-man, and Tracy the leading actor, who had sallied forth from the Kalapani dak-bungalow to try and shoot something for the family pot, suddenly found themselves the bewildered center of a cyclonic disturbance composed of a mob of howling jungle villagers.

None of the three understood a word of Gamari, which is the scornful name given to the language of these semi-apes, and means, "idiot talk," or of Hindustani, which some of the junglis might have understood; and they were amazed at the sudden attack. The menacing attitude of the mob, which circled around them with lowering brows and chattering noises, armed with the inevitable lathi, or club, needed no explanation, however, and the white men drew defensively together.

They were almost deluded into the indiscretion of firing a shot "to frighten them," after the prescribed procedure in books of travel; which would have been the signal for the shrieking dispersion of the rabble, who afterward would have produced corpses by the half-dozen before a buffalo-faced native magistrate and sworn in concert to having been attacked, all unprovoked, with field-guns, and given the native press another opportunity to froth about white brutality.

Herman was already fingering his gun nervously, when an alert, hawk-eyed young man in a khaki Norfolk-jacket and riding-breeches strode on to the scene and shouted a sharp command in the dialect.

"It is Polis-wallah!" cried the mob leaders and drew back, expecting at least arbitration if not justice.

The command had evidently meant "disperse," for on the bellowing herd drawing together and standing threateningly with lowered heads like so many cattle the man rushed at them with his empty hands, and they fled incontinently before his wrath. He grabbed an individual who appeared to be some sort of head-man and sternly demanded an explanation.

"Sahib," protested the man with a certain defiant justification in his tone, "they were shooting at peacocks!" And a chorus of angry assent came from the uncouth forms lurking at a safe distance among the trees.

"It is well," snapped the authoritative white man curtly, "Make proper report of the matter at the thana and cease from creating tumult here. Begone all of you. Beat it!" And he propelled the head-man violently from him with his foot. Then he turned to the relieved trio.'

"Say," he demanded wearily, "don't you babes in the wood know any better than to go shooting peacock in this district? Have you never heard that they're sacred, and that people like you have been beaten to death with lathis for that very reason?"

"Look here, officer," began Crandall in explanation.

The man grinned expansively.

"Oh, can that, fellers," he drawled. "I'm no crawling policeman. But the bluff went all right, didn't it?"

He chuckled delightedly and looked around with engaging good humor. There was no mistaking that dialect and that accent. Crandall held out his hand impulsively.

"Say," he joyfully guessed, "that's the pure prattle of the little old burg. You're from home, aren't you?"

"Sure I'm from home!" conceded the forceful impostor, as he shook the proffered hand as that of a long-lost brother. "And a darn long way from home," he added with a wry twist of his face, as he remembered that, so far from getting back, according to his written promise, he was compelled to devote his whole energies for the present to getting safely out of that particular district.

"MY name's Crandall," the director introduced himself. "And this is Mr. Tracy, and Mr. Herman." He looked inquiringly at the other, obviously expecting a reciprocation.

"Well," said the cheerful stranger, "since you're all allies, so to speak, in an enemy's country, I don't mind admitting that my name is Holly, Jim Holly, at present a fugitive from British Justice—with a capital J." He said it as if he had been convicted of highway-robbery.

Crandall lifted up his hands to Heaven and crowed in ecstatic thanksgiving.

"Holy crumbs!" ejaculated Holly. "What ails the man?"

"A gift!" chanted Crandall. "A gift direct from Heaven! This is my reward for living a pious life. You're the only man in the universe who can help me—Melvin told me so."

"Good for Melvin!" remarked Holly dryly. "But I'm kinder put to it to help myself just now."

"But he's after your scalp, horse, foot, and guns," added Crandall warningly.

"Do I not know it!" snorted Holly. "The landscape is fairly sprouting with his rangers. But for why the advertisement?"

Crandall took him by the arm, like a man trying to hang on to a lovely dream, and led the way back to the dak-bungalow, "to celebrate," and explained as they went.

"Fellers," began Holly when the director was but half-way through, "I'm real sorry. But it's close season with me just now, and I've got to lie so low that I just daren't go rushing 'round through the jungles with you to—"

And then he came in view of Miss Helen Redfern, the star of the company, standing on the dak-bungalow steps and watching anxiously for their return; and Holy Holly changed his mind with speed and precision, and suffered himself to be led forward and introduced. For rangers were paltry considerations after all. And danger? He had slept with it for many weeks. He should permit his soul to be vexed?

Later, over refreshment, Crandall concluded his tale of woe and wound up with:

"You see, I'll need a young menagerie; wolves, and elephants, and bears, and things. You know the story, don't you?"

Holly nodded and quickly had a suggestion.

"Wolves," he said. "Have you ever seen a Deccan wolf? Well, what about these jungly village dogs? They're the same thing, except that they haven't got bushy tails. Now why can't you doctor up their tails with spirit gum and crêpe hair?"—Where did this amazing man's knowledge of make-up come from?—"You wouldn't know the difference yourself when you were through."

Crandall gasped as he saw his way clear in a flash. He surely could. And Miss Redfern, who was known as Red Squirrel by reason of the glorious auburn of her hair, clapped her hands and squealed with merriment at the idea. This man was certainly an acquisition.

Crandall hastened to annex him to his staff with the lure of a perfectly fabulous remuneration; and Holly, with an eye to the distant prospect of his return home—which was inevitable destiny now since he had written it—and all his surplus vision on the altogether delightful profile of the Squirrel, solemnly assured Crandall that his arguments had convinced him that his fate for the present lay with the company. He suggested that if he were given a couple of coolies he would guide them to his hidden camp, and transfer his belongings to the dak-bungalow.

The cunning retreat must have been quite close, for he was back within a couple of hours; and the tenderfeet looked with astonishment on the light, compact little bundles which comprised the practical camper's outfit, all of which was a revelation to them.

"Gee, that's slick," admired Tracy. "Cunningest fixings I ever saw. But what are these two long curved things wrapped in gunny-sacking? They're heavier than all the rest of your outfit."

"Those?" said Holly with a far-away smile. "Those are the tusks of a certain elephant that Melvin's looking for up at Jagshahi. Had my eye on him for a long while."

Crandall whooped. This man was becoming more astonishing every minute.

THE next day was devoted to an earnest discussion of ways and means, and adaptations, and plans for procuring the rest of the live "properties" which would be necessary for this finest film ever made. Crandall sang about his work and attacked the problem with enthusiasm. His load of despair had miraculously vanished with the Heaven-sent advent of this purposeful young man with the engaging smile. The most important consideration, since the wolves had been provided for, was of course Mowgli's three other inseparable companions, Bagheera the black leopard, Kaa the great rock python, and, most important of all, old Baloo the big brown bear who taught the Law of the Jungle.

"Ah, yes, old Baloo," reflected Holly. "A nice fat bear now. That's difficult. Hagenbeck's agent at Calcutta was willing to give me three hundred rupees for a bear any time—and the old robber would get five for it later."

"I'll go the limit," cried Crandall joyously. "The Syndicate has saved so much money in buying the picture rights that I have carte blanche here."

"All right," said Holly quietly. "I'll go out and get one. May be gone a couple of days; and you people can utilize the time prospecting around for dog-meat."

They laughed happily at the jest. They were ready to laugh at anything that day in the lightness of their hearts.

But not long after it was found that Holly had mysteriously disappeared. And he did not come back that night; nor the next day. Crandall's heart began to sink, A horrible suspicion came to him that his godsend had been surprised by Melvin's men; though somehow that did not seem possible;—as well surprise a young panther—and he sought confirmation from his colleagues.

ON the third morning the Red Squirrel, who was standing in the veranda, shrieked and brought the men rushing to her side.

Out from the edge of the clearing came striding Holy Holly arm in arm with a huge brown bear, which swayed and shuffled along by his side on its hind legs.

Melvin was right, This Holly was positively uncanny!

He walked triumphantly up to the veranda-steps, where he smote his grim companion on the nose. The bear thereupon dropped to all fours and grumbled at being held by the ear.

"What the—where—how in thunder?" stammered the astonished film heroes.

"Some wizard! Eh?"

Holly grinned all over his face at their bewilderment. Then he tied the great beast to the veranda post—a ring through its nose and a cord were now apparent—and came up among them chuckling softly to himself.

"You city-fellers are a real treat to me," he grinned. "You look as if I was Elijah reproducing the 'Bald Head' incident. This thing is easy. India's full of performing bears and I just had to circle around till I found one; its man'll be along presently. You can't buy it, because he loves it better than his wife, and sleeps with it, and it's as tame as an old cow; but he's hired for thirty cents a day."

"Well, if that don't beat creation!" murmured Crandall weakly.

"And I heard of a fellow who's got a black leopard," continued Holly. "Just the thing you want; and same way, any traveling snake-charmer will sell you a tame python."

"What I want to know," exploded Crandall, "is why that Babu couldn't tell us some of these things."

Holly viewed the idea with derision.

"If you knew the Bengali Babu, you wouldn't want to know. It can't think spontaneously; all it's good for is routine work—and it can carry out an order, if it's very clear. Your particular jewel can best be employed rounding up the leopard-man and a snake-charmer or two."

HERMAN had been fidgeting with his boxes with professional ardor for the last two days, cleaning and oiling and testing, and then cleaning again, and was clamorous to begin work in the strong, steady light that held unvaryingly from day to day.

And then came a hitch. Tracy suddenly exhibited wild alarm as an awful thought flashed into his mind, and he sought Crandall with desperation and defiance in his face.

"See here, Crandall," he began, "who's slated to take the Mowgli part? Those great beasts may be as affectionate as fleas; but if you think I'm going to gambol with them all naked through the jungles, you're on the wrong line; ring off!"

"But my dear Tracy," Crandall shrieked, "who else is there? We've positively got nobody else."

"Get a black," grunted Tracy obstinately. "And besides, I'm too tall for the Mowgli part."

Crandall almost wept.

"Don't talk like a bicycle pump, Tracy. We'd have to rehearse him for a million years, and then he wouldn't begin to do."

But Tracy was obdurate. Nothing would induce him to do a Christian-martyr act to make a New York holiday. It was a deadlock. Crandall looked instinctively to Holly for help; he had learned to regard him as infallible.

"What 'bout dis chile?" suggested Holly. "I've never acted pictures, but I'll try any thing once."

"Would you?" said Crandall eagerly, with a touching faith—which he did not himself understand very well—in the other's ability to make good in whatever he attempted. "D'you think you could make up for it?"

Holly smiled slowly.

"I could be ready in just about fifteen minutes."

Without further questioning, Crandall forcibly pushed him into the room that acted as a dressing-apartment.

Just fifteen minutes later a perfect figure of a native youth emerged, dressed in a crooked knife and the scantiest of loincloths.

Herman jumped up and gurgled over him speechlessly, and Crandall stepped back and regarded him with his now customary amazement.

"But where did you get the stuff?" he marveled. "What make-up is this?"

Holly grinned again. He took an almost boyish delight in these dramatic surprises.

"When my biography is written," he announced, "by one of the leading philosophers of the age, you fellers'll see that I've had to make up as a native more than once; and so I wouldn't be found out either."

HERMAN was snorting with impatience to go out and make some trial film, and aided by the equally willing Crandall he dragged the venturesome new star off to where the bear and its keeper together growled defiance at a small pack of gaunt village dogs, which spent the intervals between barking and snarling in trying to chew spirit gum and crêpe hair off their tails. Scenery, of course, was all around them and Herman already had in his mind's eye an ideal little nook only a few hundred yards distant where he thirsted to make the most sensational wolf pictures ever seen.

The actual posing was surprisingly easy. The dogs lolled naturally about this most natural Mowgli's feet; and Herman bubbled over with enthusiasm as he clicked off foot after foot of gorgeous film. The light was perfect and the realism inimitable. Mowgli raised his enthusiasm a little later to a pitch of frenzy by inciting a most inspirited fight among a group of the largest and fiercest of his wolves.

Crandall moaned in ecstasy, as if it hurt him.

"Gosh, it's all in knowing how," he admired, and then swore in polyglot at the recollection of Muckerji Babu's resultless vaporings. He joined his voice to Holly's to urge the. wolves to still greater efforts and shouted aloud in sheer light-heartedness.

And then, in the middle of the joyous clamor, his jaw suddenly dropped and his eyes started from his head, as the very soul chilled within him.

Nemesis had fallen!

Through the trees rode Melvin of the Forests, with his head-ranger behind him.

Crandall was paralyzed; but Mowgli coolly set to quell the wolf-fight with kicks and shrill native abuse, and drew aside with the bear-keeper while the sahibs conversed.

Melvin's first words were reassuring.

"Well, how are you people getting on?" he greeted. "I was just over at the house looking for you."

"And for me," thought Holly quickly. "I'll bet he's heard something and come to investigate."

Crandall recovered his wits sufficiently to explain how their plans were progressing, and Herman had to demonstrate how film was produced, a novelty in which Melvin was much interested; and he stayed an interminable time talking about pictures he had seen—two-year-old releases by the time they reached India. Crandall's nerves were giving way under the strain, and he felt that he would have to scream aloud every time that Mowgli would approach with a sly grin of refined diabolism and shoo the wolves away from sniffing around the sahib's feet.

Finally Melvin mounted again, and after talking for several more excruciating minutes, he rode off slowly. Then he suddenly turned and came back, and Crandall's heart climbed up into his throat where he could taste it.

"I hear you had some turn-up with the natives," Melvin stated in his official manner. "You must be careful, you know. That's the one thing the Government will not tolerate, Mr. Crandall. I have to warn you about that." And he trotted off once more.

With reckless effrontery, Mowgli ran after him and called, "Sahib, backsheesh do. Will the Excellency see the bear dance?"

But Melvin rode on without taking any further notice.

Crandall mopped the cold perspiration from his forehead and reviled Holly murderously for the repeated shocks to his nervous system.

"Close call, wasn't it?" remarked that irresponsible coolly. "He's sure heard some talkee-talkee and come over to explore. But I guess he's satisfied we're all innocent citizens now. And so the Government won't stand for disturbances, hey?—Hm!"

After the establishment of this clean bill of health Holly felt that he could move about more freely, and arrangements advanced swimmingly; but in spite of this progress he was observed to pause from time to time and frown thoughtfully. Perhaps he was regretting that the sooner the series of pictures would be finished the sooner would the Red Squirrel pass from his sight. Who knows? The Babu returned from his errand with a small army of embryo animal-trainers, and news of more to follow.

The native of India loves to catch and cherish some live thing, and word having gone forth of a lunatic party of sahibs, they came in malodorous droves, with an appalling assortment of strange beasts and birds, which they tried to sell, at first at exorbitant prices, and later for anything they could get.

But the leopard-man was crafty, and held out for an awful hire, till Holly discovered that the Babu had told him that his animal was a necessity, and proposed to go shares on the profits. A fine big python also was secured, like film, at so much per foot—and the owners stretched it villainously in the measuring—a live snake is an astonishingly elastic beast. With the principals at hand, several more pictures were taken of Mowgli and his three companions, to Herman's imminent contentment; for Holly pushed and buffeted the beasts into the desired poses with the utmost sang-froid; but then, as Crandall said, it was all in the knowing how.

Crandall too now began to notice Holly's spasms of thoughtful preoccupation, figuring out new wonders, doubtless; and he commended his immaculate paragon's zeal. And then one day Holly smote his thigh and shouted aloud with merriment, and thought carefully a little more; and chuckled ventriloquously to himself; and then went straightway and hunted up Crandall.

"Say, Crandall," he declared persuasively, "there's one scene you ought to pull off while the chance lasts, and that's the part where Mowgli has been carried off by the monkey-people, and then Baloo and the other two rescue him, and they have the great battle with the 'Bandar Log.' Some sensational picture that!"

"You bet," agreed Crandall. "But I don't see how we're going to fake it."

"I know the stage set for it. An old temple of Hanuman, with great moss-grown steps, and a marble terrace, and a cracked water-tank, and carved pillars, and snakes, and scorpions, and millions of monkeys, and—ooh gorgeous stuff! And it isn't so far either."

Holly's description fired the director's appreciation for scene, and he called Herman to listen to it all over again.

"Gosh!" muttered the camera-man. "Are there such places as that?"

"Sure," said Holly. "Come and see."

CRANDALL was persuaded, and the three set out forthwith. A short hour's walk brought them to the outer remains of an ancient civilization; and presently there burst on their view a row of pink marble pillars, weather-worn and stained with great purple cracks, and trellised with the vivid green of the bitter karela creeper.

"Gosh!" murmured Herman. "What a picture!"

"Didn't I tell you?" exulted Holly in a whisper, even his careless irreverence subdued by the beauty of the scene. "But come and see the rest."

It was even as he had.described. A wide terrace with moss growing between the marble flags—the typical terrace where Mowgli had sat with the monkey host all around him—and a green scummy pool with pink lotus growing in it.

"This is it!" enthused Crandall. "This is the place where it all happened. Great jimminy, we'd have the picture of the age if we could only half-way fake up something."

"Leave it to me," said Holly with confidence.

They both eyed him doubtfully.

"Leave it to me," insisted Holly again mysteriously. "All you have to do is to get your tripods and boxes and things fixed up, and I'll arrange for all the monkeys in the world this very afternoon."

"Fine!" commented Crandall caustically. "But how?"

"I'll call 'em," announced Holly enigmatically. "I'll show you city-fellows some jungle magic. But at four o'clock sharp, mind; I can't work it any other time." The man talked impossibilities and Crandall and the camera-man looked at him with derision. But he spoke with easy confidence and he had certainly demonstrated his ability to accomplish wonders in the past.

They decided to take a chance, for they were both hypnotized with the gorgeous possibilities of the scene, though they could imagine no conceivable way of working it. But Holly wrapped himself in mysterious silence all the way home, and the only answer he would give to all their inquiries was:

"You leave it to me. I'll show you. You get together all your props and be there by four sharp. I'll put on my make-up and come right back—to make my magic," he added with a grin.

SHORTLY before four, Crandall and the camera-man, and Tracy who came as a skeptical spectator, and Baloo and the rest of them arrived on the deserted scene.

"E.Z. Marks and Co.," scoffed Tracy. "He's kidded you to beat the Dutch."

But Crandall loyally upheld his paragon, in spite of his saner judgment; and Herman moodily set up his instruments.

But there was wizardry in the air. Soft shufflings and low crooning calls from the tree-tops above their heads. Crandall gripped Tracy by the arm.

"My God!" he whispered hoarsely. "Look at the monkeys. The trees are swarming with them!"

It was so. High among the branches lithe brown shapes leaped and chattered and moaned plaintively by hundreds.

On the stroke of four Holly appeared suddenly from no where, looking wild in his Mowgli make-up.

"Are you all ready?" he whispered. "Well, I'll fetch 'em down; and when I call, you just sick Baloo and the bunch on, and you'll see Kipling's story as it was—and if I get bitten in the general mix-up I'll soak you for the doctor's bill."

He glided away and presently reappeared among the columns with a wreath of marigolds around his neck and a priest's bowl in his hands. He walked slowly to the center and squatted down on the bare flags and muttered occultly. Then suddenly he lifted his arms once to the tree-tops and began to rock his body to and fro, and broke into a weird chant in minor fifths with a long tremulous call between each cadence.

And from the tree-tops the monkeys answered him. They slid down the tall trunks in droves; old gray fathers, and soft-eyed mothers, and mischievous youngsters by the hundred, and came trooping up all about him, eager and unafraid. What necromancy was this? Herman reeled off his film steadily but with his breath coming in gasps. The monkeys took no notice of the unsanctified picture-people, but trooped round their Mowgli, picking at his flowers and his loin-cloth and chattering querulously.

Then suddenly Mowgli rose to his feet.

"Sick 'em on!" he yelled all unmystically, and called his pets to him.

Baloo waddled up the steps and the superb panther bounded gracefully after him; and both disappeared instantly in a wave of monkeys. The great beasts grumbled and complained indignantly, and the hordes of monkeys pinched and chattered and pulled at them, and leaped up and down on all fours on the flags and howled. And Herman danced behind his camera and howled with them; for he was getting the most wonderful picture ever filmed. And then, all of a sudden, there rose wilder and more uncouth howls all around them, and a mob of yelling natives surrounded them as once before.

Holly shouted aloud with joy.

"Look out!" he called with an inexplicable exultation in his tone. "Keep together. I'll attend to this bunch."

The amazing man seemed to have considered even this contingency, for without hesitation he seized the indignant Baloo by the scruff of the neck and rushed him at the nearest group of natives.

As the great bear and the wild-looking man bore down on them, they, who would have beaten the white men with clubs, broke and fled incontinently. Holly shouted with glee and charged the next group, and scattered them like frightened rabbits; and so on to the last. The fat old bear seemed to enter into the spirit of the game as much as he did, and together they chevvied them till not a man was left in sight. Weak with laughter, Holly returned to the bewildered film-fakers.

"Now then," he commanded briskly, "let's hustle and get home before they gather again."

On their way home he kept in fits of laughter, and in reply to their amazed inquiries only urged them to greater speed. It was not till they were safe in the dak-bungalow—where for some further mad reason he insisted on keeping on his make-up—that he condescended to explain.

"Holy Gee! You fellers are as good as taking the kids to a circus," he chuckled with tears in his eyes. "Listen how easy it is back of the scenes. Those monkeys are the sacred apes of Hanuman, and an old priest keeps up the custom of feeding them every day at four o'clock. It was easy to bribe the miserly old gink to let me take his place for the sake of the pictures, though I kinder hesitated to tell him the second part of the program. Monkeys of course will go for anything if there are enough of them; and as for old Baloo chasing the natives, why these bear-men train their beasts to chevvy them so as to carry the bluff of being ferocious man-eaters. Magic ain't so difficult when you know how. Eh, Crandall? But some picture old sport, not?"

"You bet, some picture!" enthused Herman, and would have embraced him.

That night the company slept the sleep of the just with the consciousness of work well done.

THE morning broke fair and cloudless, and with it came Melvin once again, like a bolt out of the blue sky. But it was no social call this time. He was stern and inexorable.

"I'm sorry, Mr. Crandall," he announced. "But I have telegraphic orders, and it is my duty to carry them out. I warned you twice about violating local religious customs, and yesterday's affair is the culmination. The whole district is clamoring for redress, and I have orders to send you away."

Crandall was thunderstruck. He strode nervously up and down, clasping and unclasping his hands; and spent an hour promising not to transgress again, and arguing, and finally pleading; but it was of no use. Melvin had his orders; and as an incorruptible officer of the Government it was his duty to obey.

"I'm really sorry, Mr. Crandall," he insisted. "But I must escort you out of the district."

"There's no need to escort us like criminals," growled Crandall moodily. "We'll go by ourselves."

"Oh, it's not that," Melvin hastened to explain. "But—" wearily—"my rangers are still looking for this Holly man, and they wouldn't let anybody through."

There was some small gleam of comfort in the reflection of how lucky it was that Holly had kept on his wonderful Mowgli make-up.

And then, late in the day, when Melvin had safely escorted the depressed little troupe with its beasts and baggage far beyond his lines and deposited them before the next dak-bungalow, and when his horse had finally disappeared in a cloud of dust, Holly sank to the ground and wept with silent mirth.

"Great Gosh!" growled Herman savagely. "Ain't there nothing you don't laugh at? You make me sick." And even Crandall was irritated into expostulating that there was a time for everything, and this was surely no time for laughter.

"Fellers," confessed the crafty diplomat from his position on the floor, "I've played it low-down mean on you. I figured on this. I figured Melvin would put us out, and I played for it. That district had got too hot to hold me and I couldn't see any other way out. I knew there'd be a rumpus with the black men over that picture if we got up a fight with their monkeys, and from what Melvin said before I felt pretty darn sure that the outraged majesty of the Government would give us a personally conducted tour off the premises. Forgive me; but I've got to laugh on Melvin."

Crandall was too weary and disheartened even to fell any resentment. He went heavily to the house, and the others followed. And that night Holly disappeared.

THE next two days were appalling in their depression. Crandall did not know where to turn. He was like a ship that had suddenly lost its rudder in the middle of a splendid passage; and the Babu's fatuous incompetence was accentuated by their recent meteoric progress. The men discussed Holly's conduct with deep disapproval, as disheartened men will, and agreed that it was surely low-down mean to leave them in the lurch like that as soon as he himself was safe; and the only one who could be found to defend him was the Red Squirrel.

Why, she argued, what claim had they on him? He had to look after his own interests. And he had obtained pictures for them which they never would have got otherwise. And so warmly did she uphold him that Crandall was converted once more to a less selfish view of the matter.

And then on the second evening the man himself appeared, travel-stained, but fizzling with energy; and his first words made the others feel ashamed.

"I've fixed us up, fellers," he announced. "I've just come from the Rajah of Basouni—friend of mine—shown him some good shooting at odd times. He's got a whole zoo full of animals, elephants and tigers and things; and he says we can take all the pictures we want on his private estate; says he'll be pleased to have us, and see how it's done."

Crandall realized this amazing man's usefulness more forcibly than ever after the recent horrid conviction that he had lost him, and he hastened to bind his interests with the company for good.

"Say, Holly," he proposed on the spot, "you told me that you'd wandered 'round Borneo and Java and the Treaty Ports generally. How about coming with us as general manager and conductor for the rest of the season, and then home?"

"Home?" said Holly and a slow smile lighted his eyes.

"Home!" And he looked at the Red Squirrel's altogether delightful profile again as she gazed with forced unconcern out of the window.

"Guess it suits my plans!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.